Strategic Approaches to Enhance Yield in Heterologous Biosynthetic Pathways: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Engineering

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of low yield in heterologous biosynthetic pathways, a primary bottleneck in the microbial production of high-value natural products and pharmaceuticals.

Strategic Approaches to Enhance Yield in Heterologous Biosynthetic Pathways: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Engineering

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of low yield in heterologous biosynthetic pathways, a primary bottleneck in the microbial production of high-value natural products and pharmaceuticals. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article systematically explores the fundamental principles governing heterologous expression, from initial host selection to advanced metabolic engineering strategies. It provides a methodological framework for pathway construction and optimization, details practical solutions for common production bottlenecks, and examines rigorous validation techniques for comparative chassis performance. By synthesizing current literature and emerging technologies, this work serves as a strategic guide for advancing heterologous production systems from laboratory scales to commercially viable processes, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutic agents.

Understanding the Core Principles and Challenges of Heterologous Expression

Defining Heterologous Biosynthesis and Its Industrial Significance

Heterologous biosynthesis refers to the engineering of biological pathways in a host organism that is not the native producer, enabling the production of valuable compounds like pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and fine chemicals. This approach is industrially significant as it offers a sustainable, scalable, and economically viable alternative to traditional extraction from plants or chemical synthesis, which are often limited by low yields, complex purification, and environmental concerns [1]. By transferring and optimizing metabolic pathways into tractable microbial or plant hosts such as Escherichia coli, Aspergillus species, or Nicotiana benthamiana, researchers can overcome supply chain vulnerabilities and meet growing industrial demands for bioactive molecules [2] [3].

Current Research and Data in Yield Optimization

Recent advances focus on systematic pathway engineering and host optimization to improve the titers, rates, and yields (TRY) critical for industrial adoption. The following table summarizes key findings and yield metrics from contemporary studies in heterologous production.

Table: Recent Advances in Heterologous Biosynthesis for Yield Improvement

| Target Compound | Host Organism | Key Engineering Strategy | Maximum Titer Achieved | Industrial Significance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naringenin (flavonoid) | Escherichia coli | Stepwise enzyme screening (TAL, 4CL, CHS, CHI) and use of a tyrosine-overproducing strain. | 765.9 mg/L (de novo) | High-value antioxidant & anti-inflammatory; demonstrates systematic pathway optimization [1]. | [1] |

| 10-Hydroxy-2-decenoic acid (10-HDA) | Escherichia coli | Heterologous expression of the MexHID transporter protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa for product efflux. | 0.94 g/L | Royal jelly bioactive; overcoming product toxicity and feedback inhibition is key [4]. | [4] |

| Various Terpenoids & Proteins | Aspergillus oryzae & A. niger | Exploiting native secretion capacity & eukaryotic PTMs; CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genetic modifications. | Varies (e.g., Protease: 10.8 mg/mL) | GRAS-status fungal platform for complex eukaryotic proteins and natural products [3]. | [3] |

| Plant Natural Products (e.g., Diosmin) | Nicotiana benthamiana (plant chassis) | Transient multi-gene expression via Agrobacterium infiltration. | e.g., 37.7 µg/g FW (Diosmin) | Rapid prototyping of complex plant pathways without stable transformation [2]. | [2] |

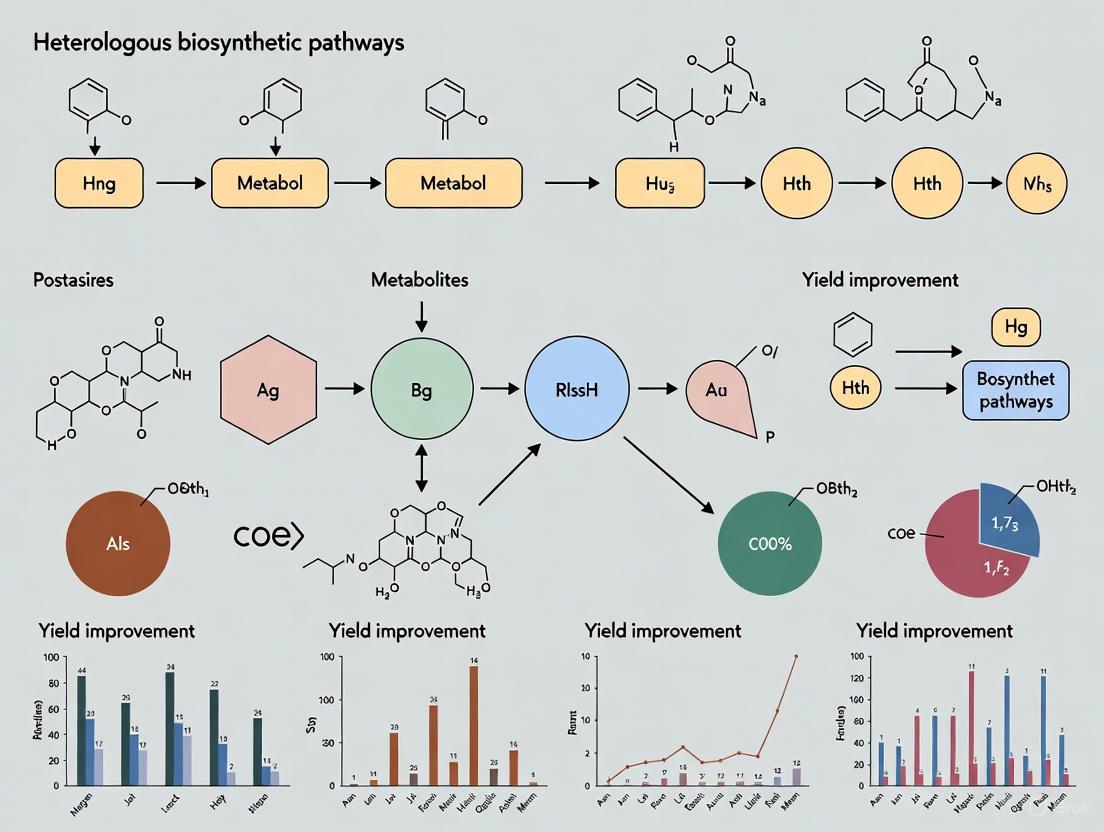

The experimental workflow for comprehensive pathway optimization, as exemplified by the naringenin case study, involves a logical sequence of design, building, and testing phases [1] [2]. The following diagram maps this iterative process.

Diagram: The iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle for optimizing heterologous biosynthetic pathways.

Experimental Protocols for Yield Enhancement

Protocol: Stepwise Pathway Assembly and Screening

This protocol, derived from high-yield naringenin production in E. coli, details a methodical approach to identifying the optimal enzyme combination for each step in a heterologous pathway [1].

- Objective: To de novo produce naringenin by sequentially validating and optimizing the expression of four enzymes: Tyrosine ammonia-lyase (TAL), 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL), chalcone synthase (CHS), and chalcone isomerase (CHI).

- Host Strain Preparation: Use engineered E. coli M-PAR-121, a tyrosine-overproducing strain, as the base chassis. Prepare competent cells for transformation [1].

- Modular Plasmid Construction: Clone genes encoding candidate enzymes from various sources (e.g., Flavobacterium johnsoniae TAL, Arabidopsis thaliana 4CL) into compatible expression vectors (e.g., pRSFDuet-1, pCDFDuet-1) with inducible promoters (e.g., T7lac) [1].

- Sequential Transformation and Screening:

- Step 1 - TAL Screening: Co-transform the base strain with plasmids expressing different TAL variants. Cultivate in production medium, induce expression, and quantify the intermediate p-coumaric acid via HPLC after 24-48 hours. Select the TAL gene yielding the highest titer (e.g., 2.54 g/L) [1].

- Step 2 - 4CL & CHS Screening: Using the best TAL strain, test combinations of 4CL and CHS genes. Quantify the product naringenin chalcone (e.g., target: 560.2 mg/L) [1].

- Step 3 - CHI Screening: Introduce different CHI genes into the best-performing strain from Step 2. The final product, naringenin, is quantified (target: >765 mg/L) [1].

- Process Optimization: With the best enzyme combination, further optimize yield by adjusting cultivation parameters such as induction timing, temperature, and carbon source concentration [1].

Protocol: Overcoming Product Toxicity via Transporter Engineering

This protocol outlines a strategy to alleviate feedback inhibition and cytotoxicity, a common barrier to high yields, as demonstrated for 10-HDA production [4].

- Objective: To enhance the yield of a toxic product (10-HDA) by engineering efflux mechanisms in an E. coli host.

- Tolerant Strain Screening: Screen environmental samples (e.g., soil) in LB medium supplemented with inhibitory concentrations (0.5-2 g/L) of the target product (10-HDA). Isolate and identify tolerant strains via 16S rRNA sequencing (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa) [4].

- Transporter Gene Mining: Annotate the genome of the tolerant strain to identify candidate efflux transporter genes (e.g., RND family pumps like MexHID). Amplify these genes via PCR [4].

- Expression in Production Host:

- Plasmid-based Expression: Clone the transporter gene into an expression plasmid (e.g., pET28a) and transform into the production E. coli strain (e.g., BL21(DE3)) [4].

- Chromosomal Integration (Advanced): For stable, tunable expression, integrate multiple copies of the transporter expression cassette into the host chromosome using CRISPR-associated transposon techniques (MUCICAT) [4].

- Validation of Function:

- Tolerance Assay: Compare the growth of transporter-expressing strains vs. control in media with high product concentrations.

- Efflux Assay: Measure intracellular vs. extracellular product concentration over time via LC-MS/MS. Successful engineering should increase the extracellular product ratio and the substrate conversion rate (e.g., up to 88.6%) [4].

- Fed-Batch Fermentation: Validate performance in a bioreactor with substrate feeding, aiming for high titers (e.g., 0.94 g/L 10-HDA) [4].

The Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Heterologous Pathways

This section provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs framed within the central thesis of improving yield in heterologous biosynthetic pathways.

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Low or No Production of Target Metabolite

- Check 1: Gene Expression & Protein Solubility

- Action: Run SDS-PAGE to confirm protein expression. If protein is in inclusion bodies, consider strategies like lower induction temperature (16-25°C), co-expression of chaperones, or using specialized host strains (e.g., E. coli SHuffle for disulfide bond formation) [5].

- Thesis Context: Low soluble enzyme levels directly limit pathway flux and final yield.

- Check 2: Precursor Availability

- Action: Quantify intracellular precursors (e.g., malonyl-CoA, tyrosine). If low, engineer the host's native metabolism to overproduce them (e.g., use feedback-resistant enzyme variants, knockout competing pathways) [1].

- Thesis Context: Insufficient precursor supply is a primary bottleneck; enhancing precursor pools is foundational to yield improvement.

- Check 3: Product Toxicity & Degradation

- Action: Test if your product inhibits cell growth. Implement transporter engineering (as in Protocol 2.2) to export the product [4]. Also, check culture stability over time to rule out enzymatic or chemical degradation.

- Thesis Context: Product toxicity caps maximum achievable titer; efflux engineering decouples production from cell viability.

Problem: High Intermediate Accumulation, Low Final Product

- Check: Pathway Bottleneck

- Action: This indicates a rate-limiting downstream step. Quantify all pathway intermediates. The enzyme acting on the most accumulated intermediate is likely suboptimal. Screen orthologs of this enzyme or modulate its expression level using promoters of different strengths [1].

- Thesis Context: Systematic identification and removal of kinetic bottlenecks are essential for balanced pathway flux and high yield.

Problem: Inconsistent Yields Between Experiments

- Check 1: Genetic Instability

- Action: For plasmid-based systems, conduct serial passage experiments without selection. If yield drops, it indicates plasmid loss. Transition to chromosomal integration (e.g., using CRISPR-Cas systems) for stable inheritance [4] [3].

- Thesis Context: Genetic instability undermines scalable, reproducible bioprocessing required for industrial translation.

- Check 2: Cultivation Parameter Sensitivity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I choose the best heterologous host for my pathway? A: The choice depends on the pathway's complexity and product.

- E. coli: Ideal for rapid prototyping, high growth, and well-established genetics. Best for pathways without complex P450s or eukaryotic PTMs. Use for compounds like naringenin [1].

- Yeast (S. cerevisiae): Offers eukaryotic organelles (ER), better for P450s, and generally higher product tolerance. Good for terpenoids and alkaloids.

- Filamentous Fungi (Aspergillus spp.): Excellent for protein secretion, native secondary metabolism, and complex PTMs. Preferred for high-value pharmaceuticals and enzymes [3].

- Plant Chassis (N. benthamiana): Used for transient expression of very complex plant pathways, especially when enzymes are membrane-bound or require specific plant organelles [2].

Q2: What are the most common reasons for poor functional expression of plant-derived enzymes in microbial hosts? A: Key issues include:

- Codon Bias: Plant codons are often suboptimal for microbial translation. Always use codon-optimized synthetic genes.

- Protein Misfolding & Lack of PTMs: Enzymes may require specific chaperones or post-translational modifications (glycosylation, phosphorylation) absent in prokaryotes. Consider switching to a eukaryotic host (yeast, fungi) or co-expressing helper proteins [5] [3].

- Incorrect Subcellular Localization: Plant enzymes may be targeted to chloroplasts or other organelles. Remove targeting peptides for cytoplasmic expression in microbes or engineer appropriate localization in the new host.

Q3: Beyond enzyme selection, what host-level strategies are critical for maximizing yield? A: Yield optimization requires systems-level engineering:

- Dynamic Pathway Control: Decouple growth from production phase using inducible promoters or metabolite-responsive biosensors to avoid metabolic burden [2].

- Cofactor Engineering: Balance and regenerate crucial cofactors (NADPH, ATP, SAM) by modulating related metabolic pathways.

- Tolerance Engineering: Use adaptive laboratory evolution or global transcriptomic analysis to identify and engineer genes conferring resistance to pathway intermediates or the final product [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Essential materials for constructing and optimizing heterologous biosynthetic pathways.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Heterologous Biosynthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Expression Hosts | Provide a chassis with enhanced precursor supply or folding capacity. | E. coli M-PAR-121: Engineered for L-tyrosine overproduction, used as a base strain for flavonoid pathways [1]. |

| Expression Vectors & Toolkits | Enable modular cloning and tunable expression of multiple pathway genes. | Duet vectors (pETDuet, pRSFDuet): Allow co-expression of 2-3 genes with different selection markers and inducer sensitivities [1]. |

| Transporter Protein Genes | Efflux toxic products to relieve feedback inhibition and increase yield. | MexHID from P. aeruginosa: An RND-family efflux pump shown to export 10-HDA in E. coli, boosting titer [4]. |

| Fungal Expression Systems | Enable functional expression of complex eukaryotic proteins and natural products. | Aspergillus oryzae platform: A GRAS host for producing terpenoids, antibodies, and enzymes requiring eukaryotic PTMs [3]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Editing Tools | Enable precise gene knockouts, knock-ins, and multiplexed genomic integration for stable pathway expression. | Used in A. niger for multi-copy gene integration to enhance enzyme production and in E. coli for chromosomal pathway assembly [4] [3]. |

Future Directions and Strategic Outlook

The future of heterologous biosynthesis lies in moving beyond static pathway expression towards intelligent, self-regulated systems. Key frontiers include:

- AI-Integrated Pathway Design: Utilizing deep learning models trained on multi-omics data to predict optimal enzyme combinations, host chassis, and potential bottlenecks before experimental construction [6].

- Dynamic Metabolic Engineering: Implementing synthetic genetic circuits that respond to metabolite levels in real-time, dynamically rerouting resources to balance growth and production, thereby maximizing yield and stability [2].

- Expanded Host Arsenal: Further development of non-traditional hosts (like other filamentous fungi or photosynthetic microbes) tailored for specific chemical classes, alongside improving transformation and editing tools for these hosts [2] [3]. The continuous integration of systems biology, machine learning, and advanced genetic tools will transform heterologous biosynthesis from a challenging endeavor into a predictable and robust platform for sustainable industrial manufacturing.

The logical relationship between core optimization strategies and the resulting improvements in key performance metrics is summarized in the following diagram.

Diagram: Core optimization strategies drive key metabolic improvements, leading to enhanced industrial performance metrics.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guide & FAQ

This guide addresses common bottlenecks in heterologous biosynthetic pathways, from gene transcription to protein secretion, providing diagnostic questions, actionable solutions, and underlying principles to improve yield [7] [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: My recombinant protein is toxic to the host cell, causing poor growth and low yield. What can I do?

- Diagnosis: Uncontrolled basal (leaky) expression of the target protein can drain cellular resources or disrupt essential processes [8].

- Solutions:

- Tune Expression: Use a tunable expression system like the Lemo21(DE3) E. coli strain, where expression of the T7 RNA polymerase inhibitor (T7 lysozyme) is controlled by an L-rhamnose-inducible promoter. Titrating L-rhamnose from 0 to 2000 µM provides precise, inverse control over target protein production [9] [8].

- Enhance Repression: Switch to a host strain with tighter promoter control. For T7 systems, use strains expressing T7 lysozyme (e.g., pLysS, pLysE, or lysY strains) to inhibit basal T7 RNA polymerase activity. For lac-based systems, ensure the host carries the lacIq allele for high repressor production [8].

- Consider Cell-Free: For highly toxic proteins, use a cell-free protein synthesis system (e.g., PURExpress) to eliminate host viability constraints [8].

Q2: My gene is integrated and present in multiple copies, but mRNA and protein levels remain low. What is the bottleneck?

- Diagnosis: This indicates a transcriptional bottleneck. The cellular machinery, specifically the availability of active transcription factors (TFs), is insufficient to drive expression from all promoters simultaneously [10] [11].

- Solutions:

- Engineer Transcription Factors (TF Engineering): Co-express a constitutively active form of a limiting TF. For example, expressing VP16-CREB in recombinant CHO cells increased monoclonal antibody and etanercept production by up to 3.9-fold by directly enhancing transcription from CMV and CRE-containing promoters [10].

- Optimize Promoter Choice: Use strong synthetic promoters, but be aware they compete for the same limited pool of TFs. Combining strong promoters with TF engineering is most effective [10].

Q3: My protein is designed for secretion but accumulates inside the cell. Where is the blockage?

- Diagnosis: The protein translocation machinery is saturated. This is a common secretory bottleneck where the capacity of the Sec translocon (in bacteria) or the ER translocation complex (in eukaryotes) is exceeded [9] [12] [13].

- Solutions:

- Harmonize Expression with Capacity: Reduce the expression level of the target gene to match the host's translocation capacity. This was shown to optimize periplasmic yield in E. coli by preventing Sec-translocon saturation [9].

- Engineer the Secretory Machinery (Push-and-Pull): Increase the flux through the translocation channel. In Pichia pastoris, engineering the cytosolic Hsp70 cycle ("Pushing" proteins into the ER) combined with engineering the ER Hsp70 cycle ("Pulling" them in) synergistically enhanced antibody fragment secretion up to 5-fold [13].

- Overexpress Key Chaperones/Folding Factors: Systematic overexpression of secretion pathway components can identify limiting factors. In Bacillus subtilis, overexpression of the chaperones prsA and the dnaK operon increased heterologous α-amylase secretion by up to 12-fold [12].

Q4: How can I computationally predict and analyze the metabolic burden of my secretory pathway?

- Diagnosis: Producing a recombinant protein, especially a large or heavily modified one, consumes significant energy and building blocks (e.g., ATP, amino acids, sugar nucleotides), which can limit growth and yield [14].

- Solution: Use genome-scale stoichiometric models that integrate metabolism with the secretory pathway. Models like iCHO2048s (for CHO cells) can compute the ATP cost per molecule of your target protein and predict its impact on cellular growth rate [14].

- Key Insight: These models reveal that highly secretory cells naturally suppress the expression of other expensive host-cell proteins to allocate resources efficiently [14].

Q5: My target protein is insoluble or forms inclusion bodies. How can I improve soluble yield?

- Diagnosis: Overexpression can overwhelm folding machinery, leading to aggregation. For disulfide-bonded proteins, expression in the reducing cytoplasm can prevent correct bond formation [8].

- Solutions:

- Lower Induction Temperature: Induce protein expression at 15–20°C to slow synthesis and favor proper folding [8].

- Use Solubility Tags: Fuse the target to a solubility tag like Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP) using vectors such as pMAL [8].

- Co-express Chaperones: Co-express chaperone systems (e.g., GroEL/GroES, DnaK/DnaJ) to assist in folding [12] [8].

- Engineer Disulfide Bond Formation: For cytoplasmic expression of disulfide-bonded proteins, use engineered strains like SHuffle E. coli, which provide an oxidative cytoplasm and express disulfide bond isomerase (DsbC) [8].

Table 1: Impact of Specific Engineering Strategies on Heterologous Protein Yield

| Bottleneck Target | Host System | Engineering Strategy | Key Factor/Component | Reported Yield Increase | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Limitation | Recombinant CHO cells | TF Engineering | Constitutively Active VP16-CREB | Up to 3.9-fold | [10] |

| Sec Translocon Saturation | E. coli (periplasm) | Expression Tuning | Lemo21(DE3) strain for precise control | Optimized yield (prevents saturation) | [9] |

| Protein Translocation/Folding | Bacillus subtilis | Combinatorial Chaperone Overexpression | PrsA lipoprotein & DnaK operon | 9 to 12-fold (AmyL/AmyS enzymes) | [12] |

| ER Translocation (Push-and-Pull) | Pichia pastoris | Engineering Hsp70 cycles | Cytosolic (SSB1) & ER (KAR2, LHS1) chaperones | Up to 5-fold (antibody fragments) | [13] |

Table 2: Computational Analysis of Secretory Protein Costs in CHO Cells (iCHO2048s Model) Data derived from [14].

| Protein Category | Example Protein | Estimated ATP Cost (Molecules per Protein) | Key Cost Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expensive Endogenous | Complex glycoproteins | High (>5,000) | Large size, multiple disulfide bonds, extensive glycosylation. |

| Average Endogenous | Typical secreted protein | Medium (Baseline) | Standard processing and folding requirements. |

| Recombinant Therapeutics | Factor VIII (F8) | 9,488 | Large size, high glycosylation, aggregation-prone. |

| Monoclonal Antibody | High | Multiple chains, ~17 disulfide bonds, glycosylation. | |

| Model Prediction | - | - | Highly secretory cells suppress expression of expensive endogenous proteins to save resources [14]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol outlines the use of a constitutively active transcription factor (VP16-CREB) to enhance recombinant protein expression in CHO cells.

1. Principle: Co-expression of VP16-CREB, a fusion of the potent VP16 activation domain to CREB, directly and strongly activates promoters containing cAMP Response Elements (CRE), such as the CMV promoter, alleviating TF availability limitations.

2. Materials:

- Cell Lines: Recombinant CHO (rCHO) cell line expressing your gene of interest (GOI) under a CRE-containing promoter (e.g., CMV).

- Vectors: Expression vector for VP16-CREB (under a constitutive promoter like EF-1α) and a control empty vector.

- Reagents: Standard cell culture media, transfection reagent (e.g., PEI), selection antibiotic (e.g., puromycin if vector has resistance gene).

3. Procedure: - Day 1: Seed rCHO cells in appropriate plates for transfection. - Day 2: Transfect cells with the VP16-CREB expression vector. Include a control transfection with the empty vector. - Day 3: Begin antibiotic selection (if applicable) to establish a stable pool or isolate clones. - Analysis: After stable integration/expression (5-7 days post-transfection): - Viable Cell Density: Monitor growth to ensure VP16-CREB expression is not cytotoxic. - Product Titer: Quantify the concentration of your recombinant protein (e.g., by ELISA) in the culture supernatant of test vs. control cells. - mRNA Level: Perform qRT-PCR on cell pellets to measure GOI transcript levels.

4. Expected Outcome: Successful VP16-CREB expression should increase GOI mRNA and corresponding protein titer by up to several-fold without negatively impacting cell growth [10].

This protocol describes a combinatorial approach to identify and overcome secretion limitations by overexpressing components of the Sec pathway.

1. Principle: Overexpressing individual and combinations of genes involved in secretion (chaperones, translocase components, signal peptidases) can reveal which factors are rate-limiting for a specific heterologous protein.

2. Materials:

- Strain: B. subtilis strain (e.g., 1A751) expressing your heterologous secretory protein (e.g., α-amylase AmyL) from a plasmid.

- Genetic Tools: Vectors or chromosomal integration systems for overexpressing B. subtilis genes (e.g., prsA, dnaK operon, secYEG, ffh).

3. Procedure: - Construct Library: Create a series of isogenic strains, each overexpressing a single candidate gene (e.g., 23 core Sec pathway genes) in the background of your producer strain. - Primary Screening: Cultivate all strains in parallel in shake flasks. Measure extracellular enzyme activity or protein concentration. - Identify Hits: Select genes whose individual overexpression gives a significant boost in secretion (e.g., prsA gave a 3.2-5.5 fold increase for α-amylases [12]). - Combinatorial Engineering: Construct strains overexpressing combinations of the top hits (e.g., prsA + dnaK operon). Test these for synergistic effects. - Fermentation Validation: Scale up the best-performing engineered strain in a fed-batch bioreactor to assess yield under controlled conditions.

4. Expected Outcome: Identification of key limiting factors (often chaperones like PrsA and DnaK). Combinatorial engineering can lead to multiplicative improvements in extracellular protein titers [12].

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram 1 Title: Transcriptional Bottleneck and TF Engineering Solution Workflow

Diagram 2 Title: Secretory Bottleneck Diagnosis and Engineering Strategy

Diagram 3 Title: Push-and-Pull Engineering to Relieve ER Translocation Bottleneck

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Strains for Overcoming Production Barriers

| Reagent/Strain Name | Category | Primary Function | Key Application / Bottleneck Addressed | Source/Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lemo21(DE3) E. coli | Expression Host | Provides tunable T7 expression via rhamnose-controlled T7 lysozyme. | Prevents toxicity & optimizes yield by matching expression to host capacity; avoids Sec-translocon saturation. | [9] [8] |

| SHuffle E. coli Strains | Expression Host | Engineered for cytosolic disulfide bond formation (oxidizing cytoplasm, DsbC present). | Soluble expression of disulfide-bonded proteins that normally aggregate in the cytoplasm. | [8] |

| VP16-CREB Expression Vector | Genetic Tool | Delivers a constitutively active transcription factor. | Alleviates transcriptional bottlenecks in mammalian cells using CMV or CRE-containing promoters. | [10] |

| pMAL Protein Fusion Vectors | Expression Vector | Fuses target protein to Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP) solubility tag. | Enhances solubility and folding of insoluble target proteins; facilitates purification. | [8] |

| Genome-Scale Model iCHO2048s | Computational Tool | Stoichiometric model integrating CHO metabolism with secretory pathway. | Predicts ATP cost, metabolic burden, and growth impact of secreting a specific recombinant protein. | [14] |

| PrsA & DnaK Operon Expression Constructs | Genetic Tool | For overexpressing key chaperones in B. subtilis. | Relieves folding/secretory bottlenecks identified via systematic screening. | [12] |

| PURExpress In Vitro Kit | Cell-Free System | Reconstituted transcription-translation system without cells. | Produces proteins toxic to living hosts or requiring special modified conditions (e.g., disulfide bonds). | [8] |

| T7 Express lysY/Iq Strains | Expression Host | Combines tight basal repression (lysY, lacIq) in a T7 system. | Reduces leaky expression, improving stability for toxic proteins and cell viability. | [8] |

Selecting the optimal host organism is a foundational decision in heterologous biosynthetic pathway research, directly impacting the yield, functionality, and scalability of target compounds such as therapeutic proteins or complex natural products [15]. This technical support center is framed within a thesis focused on systematic strategies to improve yield. It provides a comparative analysis of the three primary microbial hosts—bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi—alongside practical troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols to address common experimental challenges [16] [17].

Comparative Host Organism Selection Table

The choice of host involves balancing genetic tractability, production capacity, and post-translational capabilities. The following table summarizes key selection criteria based on current research and yield data.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Host Organisms for Heterologous Biosynthetic Pathways

| Criterion | Bacteria (e.g., E. coli) | Yeast (e.g., S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris) | Filamentous Fungi (e.g., A. niger, A. oryzae) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Yield Range | Often high for simple proteins (g/L scale) [15]. | Moderate to high; e.g., P. pastoris improved from 5 mg/L to >5 g/L in integrated optimization [17]. | Variable; heterologous proteins often lower than native. Engineered strains achieve 110–417 mg/L for proteins [16] and 8.5 to 65.6-fold improvement for terpenes [18]. |

| Key Benefits | Rapid growth, high density, inexpensive media, extensive genetic tools [15]. | Eukaryotic PTMs, GRAS status, good secretion, strong inducible promoters [15]. | Exceptional secretion capacity (grams/L for native enzymes), diverse native metabolite precursors, GRAS status for many species [16] [19] [15]. |

| Major Handicaps | Lack of eukaryotic PTMs, improper folding for complex proteins, toxic inclusion bodies [15]. | Potential hyperglycosylation, tough cell wall, metabolic burden [15]. | High background proteases, complex genetics, "silent" endogenous pathways competing for precursors [16] [19] [15]. |

| Optimal Use Case | Non-glycosylated proteins, enzymes, simple natural product pathways [20]. | Glycosylated proteins, membrane enzymes, cytochrome P450 reactions, medium-complexity pathways [15] [17]. | High-volume secretion of industrial enzymes, complex eukaryotic proteins, and fungal-type secondary metabolites (polyketides, terpenes) [16] [19] [18]. |

| Inhibitor Tolerance | Generally lower tolerance to lignocellulosic inhibitors [21]. | High; S. cerevisiae tolerated 75% hydrolysate in one study [21]. | Moderate; A. niger grew in 25% prehydrolysate and utilized diverse nutrients [21]. |

Technical Support: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: We selected a filamentous fungal host for its strong secretion, but our heterologous protein yield is extremely low compared to its native enzymes. What are the primary constraints?

- Answer: This is a common issue. The yield discrepancy can be 400-fold or more between native and heterologous proteins in fungi like Aspergillus niger [19]. Key constraints include:

- Transcriptional Inefficiency: The heterologous gene may not be integrated into a genomic locus with strong transcriptional activity [16].

- Secretion Bottlenecks: The secretory machinery (ER, Golgi, vesicles) can be overloaded or inefficient for the foreign protein, leading to ER stress and degradation via the ERAD pathway [16] [19].

- Proteolytic Degradation: Native extracellular proteases (e.g., PepA in A. niger) can degrade your product [16].

- Suboptimal Signal Peptides: The signal peptide driving secretion may not be recognized efficiently by the fungal host [19].

FAQ 2: Our bacterial expression system produces the target protein but mainly as inactive inclusion bodies. How can we shift production to soluble, active protein?

- Answer: Inclusion body formation is typical when expressing eukaryotic proteins in E. coli. Mitigation strategies include:

- Lower Induction Temperature: Reduce the growth temperature (e.g., to 18-25°C) at induction to slow protein synthesis and favor proper folding.

- Promoter and Induction Optimization: Use weaker promoters or lower inducer (e.g., IPTG) concentrations to decrease expression rate.

- Fusion Tags: Fuse the target protein to solubility-enhancing tags like maltose-binding protein (MBP) or glutathione S-transferase (GST).

- Co-express Chaperones: Co-express bacterial chaperone proteins (e.g., GroEL-GroES, DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE) to assist folding [15].

- Codon Optimization: Optimize the gene sequence for E. coli codon usage to ensure efficient and accurate translation.

FAQ 3: In a yeast host, our protein yield is acceptable, but the product shows excessive or irregular glycosylation that affects its activity. How can this be managed?

- Answer: Hyperglycosylation and non-human glycan patterns are key yeast limitations.

- Use Glyco-Engineered Strains: Employ engineered P. pastoris or S. cerevisiae strains with humanized glycosylation pathways (e.g., Δoch1 strains that prevent hypermannosylation).

- Eliminate Glycosylation Sites: If glycosylation is not required for function, use site-directed mutagenesis to remove N-linked glycosylation motifs (Asn-X-Ser/Thr) from the protein sequence.

- Choose Alternative Host: For proteins requiring specific human-like glycans, consider switching to mammalian cell systems or advanced fungal platforms engineered for humanized glycosylation [15].

FAQ 4: We are expressing a biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) for a secondary metabolite in a heterologous host, but production is "silent" (undetectable). What strategies can awaken this pathway?

- Answer: Activating silent BGCs is a central challenge in natural product discovery [22].

- Promoter Replacement: Substitute native promoters of key biosynthetic genes with strong, constitutive, or inducible promoters from the host organism [19] [18].

- Ensure Key Precursors: Modify host metabolism to ensure ample supply of required precursors (e.g., acetyl-CoA for terpenes, amino acids for NRPs). Engineering the mevalonate pathway in A. oryzae dramatically improved terpene yields [18].

- Express Positive Regulators: Clone and co-express any pathway-specific positive regulatory genes that may be missing from your construct.

- Use Dedicated Chassis: Employ highly engineered "clean" chassis strains. For actinomycete BGCs, use Streptomyces strains with deleted endogenous BGCs to reduce competition [23]. For fungal metabolites, use fungal hosts like A. niger or A. oryzae [16] [18].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol details the creation of A. niger AnN2, a chassis with reduced background secretion for improved heterologous protein production.

Objective: Delete multiple copies of a native glucoamylase gene (TeGlaA) and disrupt a major extracellular protease gene (PepA) to create a clean production host.

Materials:

- A. niger industrial strain AnN1 (or equivalent).

- CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid system for A. niger.

- Donor DNA fragments for gene deletion/disruption.

- Fungal transformation reagents (e.g., PEG-mediated protoplast transformation).

- Selection media (appropriate antibiotics).

Method:

- Design gRNAs: Design single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting conserved regions within the tandem repeats of the TeGlaA gene and the PepA gene locus.

- Construct Donor DNA: Create donor DNA fragments containing homologous arms (~500-1000 bp) flanking the target genes and a selectable marker cassette (e.g., for hygromycin resistance).

- Co-transformation: Co-transform A. niger AnN1 protoplasts with the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid (expressing Cas9 and the sgRNAs) and the donor DNA fragments.

- Selection & Screening: Plate transformations on selective media. Screen surviving colonies via PCR to confirm the deletion of 13 out of 20 TeGlaA copies and disruption of PepA.

- Marker Recycling: Use the CRISPR/Cas9 system to excise the selectable marker, resulting in the marker-free, low-background AnN2 chassis strain.

- Validation: Confirm reduced extracellular protein and glucoamylase activity in AnN2 compared to AnN1 [16].

This protocol outlines the rational engineering of central metabolism to boost precursor supply for heterologous terpene production.

Objective: Systematically modify multiple metabolic pathways (ethanol fermentation, acetyl-CoA supply, mevalonate pathway) to create a versatile high-yielding host.

Materials:

- A. oryzae wild-type strain (e.g., RIB40).

- CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing plasmids for A. oryzae.

- Donor DNA cassettes for gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and promoter replacements.

- Analytical tools (GC-MS, HPLC) for metabolome and product analysis.

Method:

- Systems Analysis: Conduct RNA-seq and metabolome analysis of the host under production conditions to identify limiting steps (e.g., low expression of mevalonate pathway genes, active ethanol fermentation diverting carbon) [18].

- Target Pathway Selection: Based on analysis, select targets:

- Shut off ethanol fermentation: Knock out pyruvate decarboxylase (pdc) and/or alcohol dehydrogenase (adh) genes.

- Enhance cytosolic acetyl-CoA: Overexpress the ATP-citrate lyase (acl) gene or enzymes of the pyruvate dehydrogenase bypass.

- Potentiate the mevalonate pathway: Overexpress rate-limiting enzymes like HMG-CoA reductase (hmgR).

- Sequential Genome Editing: Use CRISPR/Cas9 with a plasmid recycling method to iteratively introduce up to 13 genetic modifications into a single strain [18].

- Integration of Heterologous Pathway: Integrate the target terpene biosynthetic gene cluster (e.g., for pleuromutilin, aphidicolin) into defined loci (e.g., wA, niaD, pyrG) of the engineered host.

- Fermentation & Validation: Cultivate the final strain and quantify terpene yield improvements (e.g., 8.5 to 65.6-fold increases) compared to the unmodified host [18].

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

Diagram 1: Host Selection and Engineering Workflow

Diagram 2: Protein Secretion Pathway & Bottlenecks in Filamentous Fungi

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Heterologous Pathway Engineering

| Reagent/ Material | Primary Function | Example Application & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Enables precise gene knock-out, knock-in, and multiplexed editing in hosts ranging from bacteria to fungi. | Used to delete 13 glucoamylase genes in A. niger [16] and iteratively engineer 13 metabolic modifications in A. oryzae [18]. |

| Recombineering Systems (e.g., Red/ET in E. coli) | Facilitates seamless cloning and modification of large DNA constructs (>50 kb) in E. coli using short homology arms. | Crucial for capturing and refactoring large Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) prior to heterologous expression [23]. |

| Conjugation-Compatible Vectors | Allows transfer of large, non-mobilizable plasmids from E. coli to actinomycetes or fungi via bacterial conjugation. | Essential for introducing BGCs into Streptomyces hosts; improved strains like GB2005 offer better stability for repeats [23]. |

| Modular Promoter & Terminator Libraries | Provides genetic parts of varying strengths for fine-tuning gene expression within the heterologous pathway. | Key for balancing expression in multi-enzyme pathways; used with strong fungal promoters like glaA or inducible ones like amyB [16] [18]. |

| Chassis Strains with Deleted Endogenous BGCs | "Clean" host backgrounds that minimize metabolic competition and native product interference. | Streptomyces coelicolor M1152/M1154 or engineered A. niger AnN2; enhance target pathway flux and simplify product purification [16] [23]. |

| Metabolomic & Transcriptomic Analysis Kits | Tools for systems-level analysis to identify metabolic bottlenecks and gene expression limitations in the engineered host. | Used in A. oryzae to identify low MVA pathway expression and active ethanol fermentation as yield-limiting factors [18]. |

In the pursuit of scalable and sustainable bioproduction, a central thesis has emerged: maximizing yield in heterologous biosynthetic pathways is fundamentally constrained by the compatibility between the host organism and the target protein's origin. Microbial expression systems—encompassing both prokaryotic (non-fungal) and eukaryotic (fungal) platforms—serve as indispensable workhorses for producing recombinant proteins for therapeutics, enzymes, and sustainable foods [24] [25]. However, researchers consistently encounter a significant expression yield disparity when expressing proteins across these systems. Fungal proteins (e.g., from yeasts or filamentous fungi) often exhibit lower titers in bacterial hosts like E. coli, while complex non-fungal proteins (e.g., human therapeutics) can misfold or be poorly secreted in fungal hosts [26] [25].

This technical support center is designed within the context of a broader research thesis aimed at systematically diagnosing and overcoming these yield limitations. By integrating comparative analysis of host-specific genetic elements, troubleshooting common experimental failures, and applying advanced engineering strategies, we provide a structured framework to bridge the yield gap and achieve robust, high-titer production in heterologous pathways [24] [27].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common experimental challenges, organized by host system and symptom.

Bacterial Expression Systems (Non-Fungal Hosts)

Q1: I get no colonies after transforming my expression plasmid into E. coli. What should I check? [26]

- Antibiotic Selection: Verify the correct antibiotic is used for your plasmid.

- Competent Cell Viability: Test competent cells with a control plasmid (e.g., pUC19).

- Gene Toxicity: If your gene of interest (GOI) is toxic, use tighter regulation strains like BL21(DE3) pLysS or BL21-AI. Plate transformations on media containing 0.1% glucose to repress basal T7 polymerase expression during plating [26] [28].

Q2: My protein is not expressed, or the yield is very low. What are the main causes? [26] [28]

- Sequence Issues: Confirm the reading frame and absence of premature stop codons via sequencing. Check for rare codon clusters (e.g., AGG, AGA for Arg in E. coli) that can stall translation; consider using codon-enhanced strains or optimizing the gene sequence.

- Plasmid Instability: Use freshly transformed cells for expression. If using ampicillin, consider switching to carbenicillin due to ampicillin's degradation during culture [26].

- Suboptimal Induction: Titrate IPTG concentration (from 1 mM down to 0.1 mM). Lower the induction temperature (to 30°C, 25°C, or 18°C) and extend induction time to improve yield and solubility [26].

Q3: My expressed protein is entirely insoluble (found in inclusion bodies). How can I improve solubility? [26]

- Reduce Induction Rate: Lower the temperature at induction (e.g., to 18°C) and use less inducer.

- Modify Growth Medium: Use a less rich medium (e.g., M9 minimal medium) or add 1% glucose to slow metabolism.

- Test Fusion Tags: Utilize vectors with solubility-enhancing tags (e.g., MBP, SUMO).

- Cofactor Supplementation: If the protein requires a metal ion or other cofactor, add it to the growth medium.

Fungal Expression Systems (Yeast/Filamentous Fungi)

Q4: I observe low protein titers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. What strategies can boost expression? [25]

- Promoter Engineering: Use strong, tunable promoters (e.g., GAL1, TEF1, PGK1). Consider hybrid or synthetic promoters for hyper-expression [24] [25].

- Secretion Pathway Engineering: Optimize the signal peptide (e.g., α-factor pre-pro leader) and engineer the unfolded protein response (UPR) to enhance secretory capacity.

- Glycosylation Management: Humanize the glycosylation pathway by knocking out OCH1 to prevent hyper-mannosylation, which can affect protein activity and stability [25].

Q5: My filamentous fungus (e.g., Aspergillus niger) forms dense pellets, reducing protein yield. How can I improve morphology? [27]

- Genetic Morphology Engineering: Use CRISPR/Cas9 to disrupt genes responsible for cell wall aggregation, such as α-1,3-glucan synthase (agsA, agsB) and galactosaminogalactan synthase (sph3, uge3). This leads to a dispersed mycelial morphology, improving nutrient uptake and increasing biomass and protein content [27].

- Process Optimization: Employ Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to optimize fermentation conditions (carbon source, nitrogen source, pH) for dispersed growth.

Q6: How do I address proteolytic degradation of my secreted protein in fungal cultures?

- Use Protease-Deficient Strains: Employ engineered host strains with deletions of major extracellular proteases.

- Culture Condition Adjustment: Quickly separate biomass from supernatant post-fermentation, lower cultivation temperature, and adjust medium pH away from the protease optimum.

- Add Protease Inhibitors: Include compatible inhibitors like PMSF in the lysis or harvest buffer (note: PMSF is unstable in aqueous solution) [26].

Comparative Analysis: Key Factors Influencing Yield

Genetic Element Compatibility

The choice and optimization of host-specific genetic elements are critical. The table below compares core elements across major microbial hosts [24].

Table 1: Key Genetic Elements for Protein Expression in Microbial Hosts

| Element | E. coli (Prokaryote) | S. cerevisiae (Fungus) | K. phaffii (Fungus) | B. subtilis (Prokaryote) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong Promoters | T7, tac, araBAD | GAL1, TEF1, PGK1 | AOX1 (inducible), GAP (constitutive) | P43, spoVG |

| RBS/5' UTR | Shine-Dalgarno sequence | Kozak sequence (A/GCCATGG) | Kozak-like sequence | Shine-Dalgarno-like sequence |

| Common Inducers | IPTG, Arabinose | Galactose, Copper | Methanol, Glycerol | IPTG, Xylose |

| Secretion Signal | PelB, OmpA | α-factor pre-pro leader | S. cerevisiae α-factor, native PHO1 | AmyQ, SacB |

| Typical Vector | High-copy plasmids (pET, pBAD) | Episomal (2µ) or integrative | Integrative (pPICZ) | Integrative or plasmid-based |

Quantitative Yield Disparity and Engineering Outcomes

Engineering interventions can dramatically alter yield profiles. The following table summarizes key results from recent studies [25] [27].

Table 2: Impact of Engineering Strategies on Protein Yield

| Host System | Target/Strategy | Base Yield | Engineered/ Optimized Yield | Key Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Soluble expression of difficult protein | Mostly insoluble | High solubility | Lower temp (18°C), auto-induction media [26] |

| S. cerevisiae | Secreted industrial enzyme (e.g., Lipase) | ~5,000 U/L | 11,000 U/L [25] | Promoter & secretion pathway engineering |

| A. niger (Wild-type) | Mycoprotein content | ~27.5% protein | 45.91% protein [27] | Morphology engineering (CRISPR) + RSM optimization |

| A. niger (Wild-type) | Biomass production | ~7.74 g/L | 16.67 g/L [27] | Morphology engineering (CRISPR) + RSM optimization |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol outlines the genetic engineering of filamentous fungal morphology to alleviate mass transfer limitations and boost protein yield.

1. Design and Assembly of CRISPR Constructs:

- Target Selection: Identify and select sgRNAs targeting the coding sequences of aggregation genes agsA, agsB, sph3, and uge3.

- Plasmid Construction: Clone sgRNA sequences into a fungal CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid containing a Cas9 expression cassette and a selectable marker (e.g., hygromycin resistance).

2. Fungal Transformation and Screening:

- Protoplast Preparation: Cultivate wild-type A. niger spores, harvest young mycelia, and digest the cell wall using lysing enzymes to generate protoplasts.

- Transformation: Introduce the CRISPR plasmid into protoplasts using polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated transformation.

- Selection and Screening: Plate transformed protoplasts on selective regeneration media. Isolate individual transformants.

- Genotype Validation: Perform genomic DNA extraction from transformants. Use PCR amplification and sequencing of the target loci to confirm gene disruptions.

3. Phenotypic and Yield Analysis:

- Morphology Assay: Inoculate engineered and wild-type strains in liquid culture. Observe and quantify mycelial morphology (pellet size, dispersion) over time.

- Biomass and Protein Yield: Harvest mycelial biomass by filtration, dry, and weigh. Determine total protein content using standard assays (e.g., Kjeldahl or Bradford method).

4. Fermentation Optimization using RSM:

- Design of Experiments (DoE): Use a Box-Behnken design to test the interaction of key factors (e.g., carbon source concentration, nitrogen source concentration, initial pH).

- Model Building and Validation: Perform shake-flask fermentations under the designed conditions, measure biomass and protein yield, and use software to build a predictive model. Validate the model with experiments at predicted optimal conditions.

Protocol: Multi-Factor Optimization for Soluble Expression inE. coli

A systematic approach to rescue soluble expression of problematic proteins [26] [28].

1. Small-Scale Parallel Induction Test:

- Inoculate 5 mL cultures of the expression strain harboring the target plasmid.

- At mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6), induce parallel cultures under different conditions:

- Temperature: 37°C, 30°C, 25°C, 18°C.

- IPTG Concentration: 1.0 mM, 0.5 mM, 0.1 mM, 0.01 mM.

- Induce for varying durations (2-4 hours at 37°C; 4-6 hours at 30°C; overnight at 18°C).

2. Analysis of Solubility:

- Harvest cells by centrifugation. Lyse cells via sonication or lysozyme treatment.

- Separate soluble (supernatant) and insoluble (pellet) fractions by centrifugation.

- Analyze both fractions by SDS-PAGE to determine the distribution of the target protein.

3. Follow-up Optimization:

- If solubility improves at lower temperature/IPTG, scale up the best condition.

- If the protein remains insoluble, consider constructing a fusion tag vector (e.g., MBP, GST) and repeat the small-scale test.

- For proteins requiring cofactors, repeat the test in media supplemented with the required cofactor.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Systematic Troubleshooting Workflow for Yield Disparity (Max Width: 760px)

Diagram 2: Morphology Engineering Pathway in Filamentous Fungi (Max Width: 760px)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Yield Optimization Experiments

| Category | Reagent/Material | Example Product/Catalog | Primary Function in Yield Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pET Series Vectors (for E. coli) | Novagen pET-28a(+) | High-level, inducible T7-driven expression in bacterial hosts [24]. |

| pPICZ Series Vectors (for K. phaffii) | Thermo Fisher Scientific pPICZ A | Methanol-inducible, zeocin-resistant vectors for protein secretion in yeast [24]. | |

| Engineered Host Strains | E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS | Thermo Fisher Scientific C302003 | Provides tighter control of basal expression for toxic genes via T7 lysozyme [26]. |

| S. cerevisiae BY4741 Δoch1 | Common lab strain | Knocked-out α-1,6-mannosyltransferase to prevent hypermannosylation for humanized glycosylation [25]. | |

| Genetic Toolkits | CRISPR-Cas9 Plasmid for Fungi | e.g., Addgene #118159 | Enables targeted gene knockouts (e.g., agsA) for morphology engineering [27]. |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | NEB #E2611L | Facilitates seamless cloning of multiple DNA fragments for pathway assembly. | |

| Culture & Induction | Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) | GoldBio I2481C | Standard inducer for lac/T7-based systems in bacteria; concentration optimization is critical [26]. |

| L-Arabinose (for pBAD/araBAD systems) | Sigma-Aldisk A3256 | Inducer for tight, titratable expression in E. coli; useful for toxic proteins [26]. | |

| Analysis & Purification | Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (EDTA-free) | Roche 04693159001 | Prevents proteolytic degradation during cell lysis and protein purification [26]. |

| Ni-NTA Agarose Resin | Qiagen 30210 | Immobilized metal affinity chromatography resin for purifying polyhistidine (His)-tagged proteins. | |

| Fermentation Optimization | Response Surface Methodology Software | Design-Expert, Minitab | Statistical software for designing experiments and modeling complex variable interactions to optimize yield [27]. |

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Heterologous Pathway Optimization. This resource provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to address common experimental challenges related to protein folding, modification, and transport, with the goal of improving yield in heterologous biosynthetic pathways.

Molecular Chaperone Systems: Folding & Yield Optimization

Molecular chaperones are essential for rescuing misfolded proteins and preventing aggregation, directly impacting the functional yield of heterologously expressed enzymes [29].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Soluble Protein Yield

- Problem: Most target protein is found in the insoluble fraction (inclusion bodies).

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Overwhelmed Host Folding Machinery. Expression is too fast for chaperones to fold the protein [30].

- Solution: Lower induction temperature (e.g., to 25-30°C) or reduce inducer concentration to slow translation [30].

- Cause 2: Insufficient Chaperone Capacity. Native host chaperone levels are inadequate for the target protein [29].

- Solution: Co-express chaperone plasmids (e.g., GroEL/GroES for E. coli). Pre-induction stress (e.g., 42°C heat shock, 3% ethanol) can upregulate endogenous heat shock proteins [30].

- Cause 3: Incorrect Chaperone Stoichiometry. Paradoxically, high concentrations of some RNA/protein chaperones can decrease native yield by repeatedly unfolding substrates [29].

- Solution: Titrate chaperone co-expression levels. Monitor functional activity, not just total protein.

- Cause 1: Overwhelmed Host Folding Machinery. Expression is too fast for chaperones to fold the protein [30].

FAQ: Molecular Chaperones

- Q: Why does increasing chaperone concentration sometimes decrease my final functional yield?

- A: This phenomenon, observed with chaperones like CYT-19, is explained by the Iterative Annealing Mechanism (IAM). While chaperones resolve kinetic traps, they can also unfold native states. An optimal concentration maximizes the product of the folding rate and native yield within a biological timeframe, not the absolute equilibrium yield [29].

- Q: How are chaperone activities regulated in the cell?

- A: Chaperone function is precisely tuned by post-translational modifications (PTMs). For example, phosphorylation of Hsp70 at a specific tyrosine residue (Y525) can alter its subcellular localization, affecting its client interactions [31]. A complex "chaperone code" of PTMs likely regulates activity, specificity, and localization [31].

Experimental Protocol: Testing Chaperone Co-expression for Solubility

- Clone your target gene into an expression vector with a different antibiotic resistance than your chaperone plasmid.

- Transform both plasmids into your expression host. Include controls with the target gene alone and the empty chaperone vector.

- Induce Expression at a lowered temperature (e.g., 25°C). For E. coli, you may pre-treat cultures with a mild stressor (e.g., 42°C for 15-30 minutes) before induction to induce endogenous chaperones [30].

- Lysate Fractionation: Lyse cells and centrifuge at high speed (>15,000 x g). Separate supernatant (soluble) and pellet (insoluble) fractions [30].

- Analysis: Analyze both fractions by SDS-PAGE and Western Blot or activity assays to quantify soluble, functional protein [30].

Data Presentation: Chaperone Mechanism

Table 1: Comparison of Chaperone Folding Mechanisms [29]

| Chaperone System | Primary Substrate | Proposed Mechanism | Key Effect of Increasing [Chaperone] | Optimization Goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GroEL/GroES (E. coli) | Proteins (e.g., Rubisco) | Iterative Annealing (IAM) in an enclosed cage | Increases native state yield | Maximize final yield |

| CYT-19 | RNA (e.g., Tetrahymena ribozyme) | Iterative Annealing (IAM) | Can decrease steady-state native yield | Maximize (rate x yield) product |

Visualization: Chaperone-Assisted Folding via Iterative Annealing

Diagram 1: Generalized model of chaperone-assisted folding via Iterative Annealing [29].

Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): Compatibility & Engineering

PTMs are often required for proper folding, stability, and activity of eukaryotic proteins and are a major bottleneck in prokaryotic expression systems [32].

Troubleshooting Guide: PTM-Related Expression Failure

- Problem: Protein is expressed but insoluble or inactive in a bacterial host.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Missing Essential PTMs. The host lacks machinery for modifications critical for folding (e.g., disulfide bonds, glycosylation) [32].

- Solution: Switch to a eukaryotic host (yeast, insect cells). For E. coli, use engineered strains (e.g., Origami for disulfides) or co-express modifying enzymes [30].

- Cause 2: PTM-Induced Aggregation. Some PTM sites correlate with aggregation in non-native hosts [32].

- Solution: Use bioinformatic tools (e.g., PROSITE, CSS-Palm) to predict PTM sites. Consider mutagenesis to remove problematic sites (e.g., non-consensus N-glycosylation) if functionality permits [32].

- Cause 3: Inefficient Secretion. Signal peptides for vesicular transport may not be recognized.

- Solution: Replace native signal peptide with one optimized for your host (e.g., α-factor for yeast).

- Cause 1: Missing Essential PTMs. The host lacks machinery for modifications critical for folding (e.g., disulfide bonds, glycosylation) [32].

FAQ: Post-Translational Modifications

- Q: Which PTMs are most likely to cause soluble expression failure in E. coli?

- A: Bioinformatic analysis of 1488 human proteins expressed in E. coli showed that predicted N-glycosylation, myristoylation, palmitoylation, and disulfide bond formation sites significantly correlated with insoluble expression or failure to express [32].

- Q: Do all PTMs negatively impact bacterial expression?

- A: No. Surprisingly, the predicted presence of phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, and prenylation sites correlated with successful soluble expression. This may be because these modifications often occur on surface-accessible, structured regions rather than being essential for initial folding [32].

Experimental Protocol: Bioinformatics Screen for Problematic PTMs

- Sequence Analysis: Submit your target protein sequence to predictive servers:

- Correlation Assessment: Cross-reference predictions with solubility databases (e.g., TargetTrack). Prioritize modifications known to be difficult in your chosen host [32].

- Design Strategy: For essential PTMs absent in your host, consider host change, co-expression, or in vitro modification. For aggregation-prone motifs, consider site-directed mutagenesis if structurally justified.

Data Presentation: PTM Impact on Expression

Table 2: Correlation of Predicted PTMs with Soluble Expression in E. coli [32]

| Post-Translational Modification | Correlation with Soluble Expression in E. coli | Potential Rationale | Recommended Action for Pathway Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-Glycosylation | Strong Negative | Bacterial inability to glycosylate leads to aggregation of hydrophobic sequons [32]. | Use yeast/insect cell host; remove NXS/T sites via mutagenesis. |

| Disulfide Bond Formation | Strong Negative | Oxidizing cytoplasmic environment improper for correct bond formation [32]. | Use engineered E. coli strains (e.g., Origami), target to periplasm, or use eukaryotic host. |

| Myristoylation & Palmitoylation | Negative | Lipid anchors cause membrane association/aggregation in bacteria [32]. | Co-express modifying enzymes or use eukaryotic host. |

| Phosphorylation, SUMOylation | Positive | Sites often located in soluble, structured domains; not folding-critical in test system [32]. | Typically not a primary barrier; may enhance stability. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

- Chaperone Plasmid Kits: Commercial kits (e.g., Takara's Chaperone Plasmid Set) for co-expressing GroEL/GroES, DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE in E. coli [30].

- Specialized E. coli Strains:

- Fusion Tags: MBP (maltose-binding protein), Trx (thioredoxin) to enhance solubility [30]. Include protease cleavage sites (e.g., TEV) for tag removal.

- Protease-Deficient Strains: E. coli BL21(DE3) to minimize target protein degradation.

Vesicular Transport & Secretory Pathway Engineering

Efficient vesicular transport is crucial for secreting pathway enzymes or final products, compartmentalizing reactions, and reducing intracellular toxicity.

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor Secretion or Localization

- Problem: Protein is not secreted or incorrectly localized despite a signal peptide.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inefficient ER Translocation/Signal Sequence. The signal peptide is not optimal for the host.

- Solution: Use host-optimized signal peptides (e.g., yeast α-factor, B. subtilis sacB). Validate with secretion assays.

- Cause 2: Block in Vesicular Trafficking. Protein is retained in ER or Golgi.

- Solution: Check for missing/improper PTMs (e.g., glycosylation) required for forward trafficking. Consider co-expressing trafficking chaperones.

- Cause 3: Using Vesicles as Delivery Tools (EVs): Low drug loading or targeting efficiency.

- Solution: For Extracellular Vesicles (EVs), use pre-isolation engineering (genetic modification of parent cells) or post-isolation modification (click chemistry, surface fusion) to decorate EVs with targeting ligands [33].

- Cause 1: Inefficient ER Translocation/Signal Sequence. The signal peptide is not optimal for the host.

FAQ: Vesicular Transport & Extracellular Vesicles

- Q: What are the main types of coated vesicles in secretory trafficking?

- A: COPII-coated vesicles bud from the ER to the Golgi. COPI-coated vesicles mediate retrograde transport within the Golgi and from Golgi to ER. Clathrin-coated vesicles transport from the trans-Golgi network to lysosomes/vacuoles and from the plasma membrane during endocytosis [34].

- Q: How can Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) be engineered for therapeutic delivery in synthetic pathways?

- A: EVs can be modified via pre-isolation (genetic engineering of parent cells to display targeting proteins) or post-isolation methods (chemical conjugation, membrane fusion to attach drugs or targeting moieties) [33]. This allows for targeted delivery of pathway enzymes or toxic intermediates.

Experimental Protocol: Stepwise Optimization of a Heterologous Pathway (Case Study: Naringenin in E. coli)

This protocol exemplifies a systematic approach to maximize yield [1].

- Step 1 - Substrate (p-Coumaric Acid) Optimization:

- Action: Express tyrosine ammonia-lyase (TAL) genes from different sources (Flavobacterium johnsoniae, Rhodotorula glutinis) in various E. coli strains (BL21, MG1655, tyrosine-overproducer M-PAR-121).

- Validation: Measure p-coumaric acid titer. Select the highest-producing strain/enzyme combination (e.g., M-PAR-121 with FjTAL produced 2.54 g/L) [1].

- Step 2 - Intermediate (Naringenin Chalcone) Optimization:

- Action: In the optimized strain from Step 1, express different 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL) and chalcone synthase (CHS) gene combinations.

- Validation: Measure naringenin chalcone. Select the best combination (e.g., At4CL + CmCHS produced 560.2 mg/L) [1].

- Step 3 - Final Product (Naringenin) Optimization:

- Action: Introduce different chalcone isomerase (CHI) genes into the optimized pathway from Step 2.

- Validation: Measure final naringenin titer. Select the best CHI (e.g., MsCHI from Medicago sativa yielded 765.9 mg/L) [1].

- Step 4 - Process Optimization:

- Action: Fine-tune cultivation parameters (induction timing, carbon source concentration, feeding strategy) for the complete, optimized pathway.

Data Presentation: Heterologous Host Selection & Pathway Optimization

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Host Organisms for Heterologous Expression [15]

| Host Organism | Key Benefits | Major Handicaps for Pathway Engineering | Example Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria (E. coli) | Fast growth, high protein yield, extensive genetic tools [15]. | Limited PTM capacity, potential inclusion body formation [15] [32]. | Escherichia coli |

| Yeast | Eukaryotic PTMs, generally recognized as safe (GRAS), good protein folding [15]. | Hyper-glycosylation possible, lower diversity of native precursors [15]. | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris |

| Filamentous Fungi | High secondary metabolite diversity, excellent secretion [15]. | Complex native metabolism competes for precursors, slower genetic manipulation [15]. | Aspergillus niger |

| Mammalian Cells | Most authentic human PTMs, proper folding of complex proteins [15]. | Very high cost, slow growth, low yield [15]. | HEK293, CHO cells |

Visualization: Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis & Engineering

Diagram 2: Exosome biogenesis and engineering strategies for targeted delivery [33].

Practical Strategies for Pathway Construction and Expression Enhancement

Promoter Engineering and Transcriptional Optimization Techniques

This technical support center provides targeted solutions for researchers optimizing heterologous biosynthetic pathways to improve compound yield. Promoter engineering is a foundational metabolic engineering strategy for maximizing the production of valuable secondary metabolites and proteins in a host organism [15]. Transcriptional optimization involves precisely tuning the expression levels of pathway genes, a critical step as the simple introduction of foreign genes rarely results in successful, high-yield expression [15]. The guidance here, framed within the context of yield improvement for drug development and biochemical production, addresses common experimental hurdles with practical troubleshooting, proven protocols, and essential resource lists.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: I have cloned my biosynthetic pathway into a standard expression vector, but the final product yield is extremely low or undetectable. What are the first elements I should troubleshoot?

- Primary Issue: Suboptimal transcriptional control of pathway genes.

- Diagnosis & Solution:

- Verify Promoter-Host Compatibility: The promoter must be functional in your chosen host. A strong E. coli promoter may be silent in yeast or fungal systems. Consult host-specific literature for validated promoters [15].

- Check Promoter Strength Mismatch: A rate-limiting enzyme may be under-expressed, or a toxic intermediate may be overproduced. Measure transcript levels (e.g., via RT-qPCR) for each pathway gene to identify bottlenecks or imbalances.

- Consider Inducible vs. Constitutive Expression: For pathways producing toxic intermediates, switch from a strong constitutive promoter to a tightly regulated inducible system (e.g., PAOX1 in Pichia pastoris) [15] to separate growth and production phases.

- Recommended Action: Implement a promoter screening strategy. Clone the rate-limiting gene(s) under the control of a library of promoters with varying strengths and measure the impact on yield [35].

Q2: How do I select the best promoter for a specific gene in my pathway?

- Strategy: Use a combined bioinformatic and experimental screening approach.

- Bioinformatic Screening: For your host organism, analyze RNA-seq data to identify genes with consistently high transcript levels. The promoters upstream of these genes are candidates for strong, endogenous promoters [35].

- Experimental Validation: Clone candidate promoters to drive a reporter gene (e.g., GFP, lacZ) and measure fluorescence or enzyme activity. This quantitative reporter assay will rank promoter strength reliably [35].

- Library Construction: Assemble a library of 5-10 promoters with a wide range of measured strengths. Use this library to systematically vary the expression of each pathway gene [35].

Q3: My pathway expression causes severe growth retardation or cell death in the host. How can I overcome this?

- Likely Cause: Metabolic burden, toxicity of pathway intermediates, or resource competition.

- Solutions:

- Fine-Tune Expression: Replace a very strong promoter with a moderately strong one to reduce the burden. Information theory principles suggest matching expression noise and dynamic range is key to optimal function [36].

- Use Inducible Promoters: Decouple cell growth from product synthesis. Grow the culture to high density under repressive conditions, then induce pathway expression [15].

- Engineer the Host: Modify the host genome to bolster precursor supply or delete competing pathways. For example, in a PHA production strain, deleting the glucose dehydrogenase (gcd) gene redirected carbon flux and increased yield by ~5% [35].

Q4: I need to co-express multiple genes in a pathway. How do I manage their relative expression levels?

- Core Approach: Promoter balancing and vector strategy.

- Promoter Balancing: Use the promoter library (see Q2) to assign different-strength promoters to each gene. Avoid using the identical strong promoter for all genes.

- Chromosomal Integration vs. Plasmids: For long-term stability, integrate gene cassettes into the host genome. Use different selectable markers or a site-specific recombination system for sequential integration [35].

- Polycistronic vs. Monocistronic Design: In prokaryotes, consider operons. In eukaryotes, express each gene from its own promoter and terminator to allow individual tuning.

Q5: Computational tools are recommended for pathway design. Which ones are useful for promoter and transcriptional optimization?

- For Pathway Expansion & Enzyme Prediction: Tools like BNICE.ch and BridgIT can predict novel enzymatic reactions to create derivatives of your target compound and suggest enzymes that might catalyze these steps [37].

- For Host Selection & Analysis: Refer to curated databases and models for well-studied hosts (e.g., S. cerevisiae, P. putida) [15]. For novel hosts, perform RNA-seq to identify strong native promoters [35].

- For Theoretical Optimization: Concepts from information theory can provide a framework for understanding the maximum informational capacity of a promoter-transcription factor system [36].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Screening Endogenous Strong Promoters via RNA-seq and Reporter Assay

This protocol is adapted from a successful study enhancing polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production in Pseudomonas putida [35].

- Culture & RNA Extraction: Grow your host organism under standard and production-relevant conditions in biological triplicate. Harvest cells at mid-log phase and extract total RNA.

- RNA-seq & Bioinformatic Analysis: Perform paired-end RNA sequencing. Map reads to the host genome and calculate gene expression values (e.g., FPKM or TPM). Select the top 30-50 genes with the highest and most stable expression across conditions [35].

- Promoter Cloning: Identify the genomic region ~300-500 bp upstream of the start codon for each target gene. Amplify these regions via PCR.

- Reporter Construct Assembly: Clone each promoter fragment into a shuttle vector upstream of a promoterless reporter gene (e.g., gfp or lacZ). Transform the library into the host.

- Promoter Strength Characterization: Measure reporter output (fluorescence/activity) in a microtiter plate reader during growth. Normalize the signal to cell density (OD600). Rank promoters by their maximum normalized activity.

Protocol 2: Optimizing a Biosynthetic Pathway via Promoter Substitution

This protocol details the chromosomal integration of optimized promoters to tune a heterologous pathway [35].

- Identify Rate-Limiting Step(s): Use transcriptomics or proteomics on an initial pathway strain to identify genes with disproportionately low expression.

- Design Integration Cassettes: For each gene to be optimized, create a DNA cassette containing: your selected promoter, the gene's open reading frame, and a downstream terminator. Flank this cassette with ~500 bp homology arms targeting the desired chromosomal locus (often the native gene locus).

- Vector Construction & Transformation: Clone the cassette into a suicide vector (e.g., with a counter-selectable marker like sacB). Introduce the vector into the host and select for first crossover events.

- Selection & Screening: Apply counter-selection to force a second recombination event, leading to promoter replacement. Verify integration via colony PCR and sequencing.

- Performance Assay: Ferment the engineered strain alongside the control. Measure final product titer, yield, and cell dry weight. Iterate by testing different promoter strengths.

Key Data and Host Selection Reference

Table 1: Performance Data from Promoter Engineering in PHA Production

Data from a study replacing the native promoter of the PHA synthase gene (phaC1) and other genes in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 [35].

| Engineered Strain | Modification | Relative PHA Yield (% of cell dry weight) | Absolute PHA Yield (g/L) | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KTU (Parent) | None | ~22% (baseline) | ~0.64 (baseline) | Baseline strain |

| KTU-P46C1 | Strong promoter P46 driving phaC1 | 33.24% | N/A | +51% in relative yield |

| KTU-P46C1-∆gcd | P46 driving phaC1, gcd gene deleted | 38.53% | N/A | +5.29% from deletion |

| KTU-P46C1A-∆gcd | P46 driving phaC1 & acoA, gcd deleted | ~42% | 1.70 | +90% relative yield, +165% absolute titer |

Table 2: Common Heterologous Hosts for Biosynthetic Pathways

Summary of benefits and handicaps for different host systems [15].

| Host System | Key Benefits | Primary Handicaps | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast (e.g., S. cerevisiae) | Low cost, fast growth, GRAS status, good protein processing, strong genetic tools [15]. | Hyperglycosylation potential, limited native precursors. | Eukaryotic proteins, terpenoids, alkaloids [37]. |

| Filamentous Fungi (e.g., Aspergillus) | High secretion capacity, rich secondary metabolism [15]. | Complex genetics, background metabolism. | Fungal natural products, industrial enzymes. |

| Plants / Plant Cells | Correct compartmentalization, suits plant pathways [15]. | Slow growth, complex transformation. | Very large proteins or complex plant metabolites. |

| Bacteria (e.g., E. coli, P. putida) | Very fast growth, inexpensive media, high expression, simple genetics [15]. | Lack of eukaryotic protein processing, potential toxicity. | Prokaryotic pathways, simple eukaryotic proteins, organic acids [35]. |

Visual Guide: Promoter Engineering Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function & Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Promoterless Reporter Vector | Quantitative measurement of promoter strength. Essential for screening. | Plasmid with GFP, RFP, or lacZ lacking a promoter [35]. |

| Shuttle Vectors | Cloning and expression in multiple hosts (e.g., E. coli and your target host). | pBBR1MCS series for Pseudomonas [35]. |

| Suicide Vectors | Enables stable chromosomal integration via homologous recombination. | Contains counter-selectable marker like sacB for genome editing [35]. |

| RNA-seq Kit | Identifies highly transcribed native genes for endogenous promoter discovery. | Commercial kits for bacterial, yeast, or fungal RNA extraction and library prep. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Validates transcript levels for pathway genes during troubleshooting. | SYBR Green or probe-based mixes for your host organism. |

| Inducer Compounds | Controls expression from inducible promoters (on/off, graded response). | Methanol (PAOX1), Tetracycline (Tet-On), Galactose (GAL1/10) [15]. |

In heterologous biosynthetic pathway research, a primary objective is to maximize the yield of a target compound, such as a therapeutic drug precursor or a valuable chemical. A fundamental strategy involves increasing the copy number of genes encoding rate-limiting enzymes to overcome metabolic bottlenecks and enhance flux toward the product [38]. This process, the strategic amplification of target gene dosage, is a core tool in the metabolic engineer's arsenal [39].

However, simply increasing gene copy number does not guarantee success. Cellular metabolism is a tightly regulated network. The Gene Dosage Balance Hypothesis (GDBH) states that stoichiometric imbalances in protein complexes or interconnected pathways can lead to fitness defects, dominant negative phenotypes, and reduced productivity [40]. For example, overexpressing a single subunit of a multi-enzyme complex can titrate other essential partners, leading to the formation of non-functional subcomplexes and a decrease in overall pathway efficiency [41].