In Vitro Reconstitution of Biosynthetic Pathways: A Foundational Guide from Discovery to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the in vitro reconstitution of biosynthetic pathways, a powerful methodology that excises enzymatic pathways from their native cellular environments for detailed study and...

In Vitro Reconstitution of Biosynthetic Pathways: A Foundational Guide from Discovery to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the in vitro reconstitution of biosynthetic pathways, a powerful methodology that excises enzymatic pathways from their native cellular environments for detailed study and engineering. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of this approach, from uncovering novel biochemical logic to optimizing multi-enzyme systems for high-yield production. We detail cutting-edge cell-free platforms for rapid pathway prototyping, systematic strategies for troubleshooting and enhancing pathway efficiency, and methods for validating reconstituted systems and comparing their performance across biological species. The insights gained from in vitro studies are instrumental for advancing metabolic engineering, synthetic biology, and the development of novel therapeutics and biofuels.

Unveiling Nature's Biochemical Blueprint: Core Principles and Discovery

The in vitro reconstitution of biosynthetic pathways represents a cornerstone of modern biochemical research, enabling the detailed study of enzymatic mechanisms, kinetics, and pathway optimization outside the complex environment of the living cell [1]. This approach has evolved dramatically from its origins in early enzymology to become a powerful platform for drug development and the production of complex natural products [2] [3]. The journey from Eduard Buchner's seminal demonstration of cell-free fermentation to contemporary systems utilizing recombinant lysates illustrates a fundamental paradigm shift in how scientists harness and study enzymatic cascades [4] [3]. This Application Note traces this critical methodological evolution, providing historical context and detailed protocols that frame in vitro reconstitution as an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals.

Historical Foundations: From Vitalism to Biochemical Analysis

The conceptual foundation for in vitro reconstitution was laid in 1897 when Eduard Buchner demonstrated that a cell-free yeast extract could ferment sugar into alcohol [1] [5]. This discovery was transformative, delivering the final blow to vitalism—the doctrine that life processes required an intangible "life-force" and could not occur outside living cells [4]. Buchner's "zymase" preparation proved that biochemical transformations were driven by special substances, enzymes, formed in cells but capable of functioning independently [5]. This established the fundamental principle that complex metabolic pathways could be excised from their cellular context and studied in isolation [1].

Key 20th Century Developments

The following decades witnessed critical advancements that expanded the scope and sophistication of in vitro pathway analysis:

- Enzyme Crystallization and Protein Nature: In 1926, James B. Sumner crystallized the first enzyme (urease) and confirmed its protein nature, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1946 [4].

- Early Industrial Applications: By the mid-20th century, multi-enzyme processes were being used industrially. A notable example, still in use today, is the whole-yeast catalyzed condensation of acetaldehyde with benzaldehyde to produce l-phenylacetylcarbinol, a precursor to the stimulant l-ephedrine [4].

- Steroid Biotransformation: In the early 1950s, fungi were used for the regio-selective hydroxylation of steroids to produce cortisone, showcasing the power of biocatalysis for transformations that were impossible using purely chemical means [4].

Table 1: Historical Milestones in In Vitro Reconstitution

| Year | Scientist/Development | Key Achievement | Impact on In Vitro Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1897 | Eduard Buchner | Discovery of cell-free fermentation using yeast extract [5] | Established that metabolic processes can occur outside living cells |

| 1926 | James B. Sumner | Crystallization of urease, proving the protein nature of enzymes [4] | Enabled detailed structural and mechanistic studies of enzymes |

| 1913 | Michaelis & Menten | Development of enzyme kinetics model [4] | Provided a quantitative framework for analyzing enzyme activity in vitro |

| Early 1950s | Various | Microbial hydroxylation of steroids for cortisone production [4] | Demonstrated the industrial potential of enzymatic biotransformations |

The Modern Platform: Recombinant Cell-Free Systems

The advent of recombinant DNA technology marked a revolution, transforming in vitro reconstitution from a crude, analytical tool into a precise and engineerable platform for complex biosynthesis [3]. Modern systems typically use clarified lysates from engineered organisms like E. coli, which are overexpressed with heterologous enzymes to create a tailored catalytic milieu [3]. This "third route" to biocatalysis offers a powerful alternative to both whole-cell systems and approaches using purified enzymes, combining the best features of each.

Advantages of the Modern Recombinant Lysate Platform

- Elimination of Cellular Barriers: The absence of a cell membrane removes transport limitations and eliminates concerns about substrate, intermediate, or product toxicity [3].

- High Fidelity and Control: Researchers gain direct, unrestricted control over reaction parameters, including substrate and catalyst loading, pH, and redox potential [2].

- Cofactor Recycling: Endogenous enzymes from the lysate can be recruited to regenerate essential and expensive cofactors like ATP and NAD(P)H, overcoming a major economic and practical hurdle of purified enzyme systems [3].

- Single-Pot Multistep Synthesis: Enzymes from diverse organisms can be combined in a single pot to create artificial biosynthetic pathways for complex chemicals from simple building blocks [3].

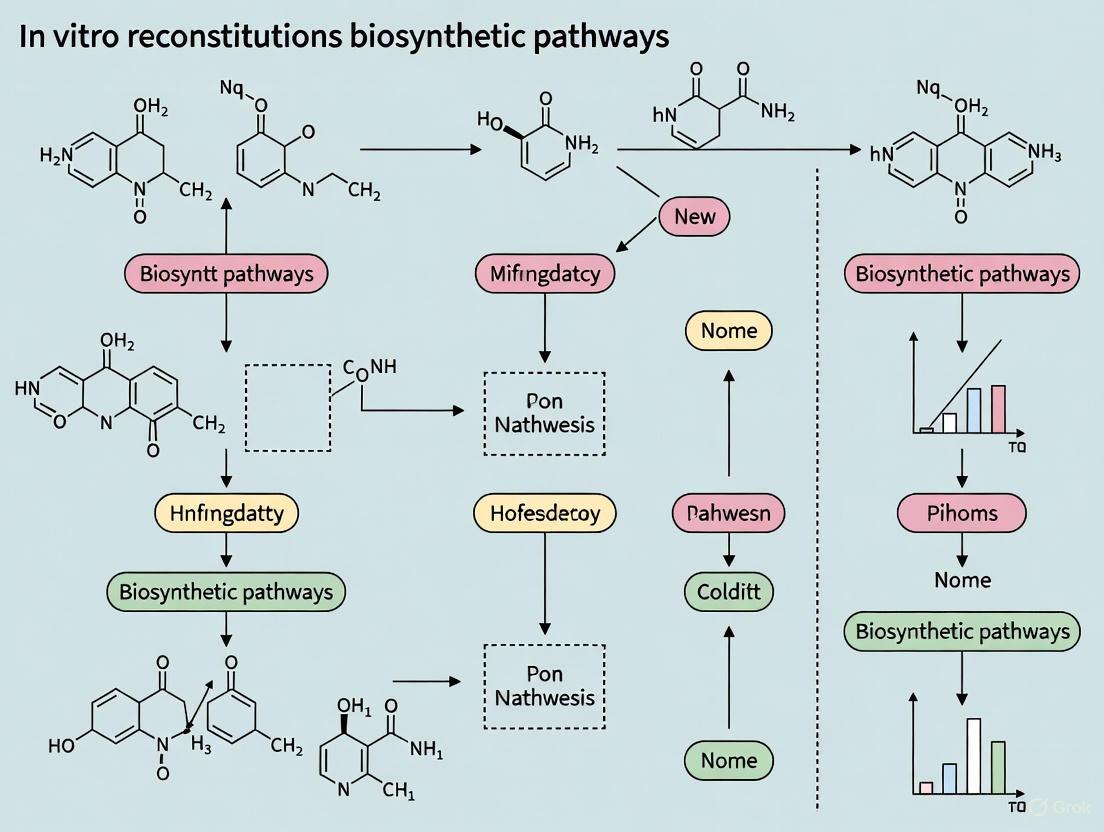

The diagram below illustrates the logical and experimental workflow that connects historical foundations to modern applications in pathway reconstitution.

Application Note: Targeted In Vitro Reconstitution for Pathway Optimization

The following protocol outlines a strategy known as "targeted engineering," where an in vitro reconstituted system is used to guide the efficient engineering of high-yielding microbial cell factories [2]. This approach systematically eliminates the background complexity of living cells to identify rate-limiting steps and optimize pathway flux.

Protocol: A Targeted Workflow for Biosynthetic Pathway Optimization

Objective: To reconstitute a multi-enzyme biosynthetic pathway in vitro in order to identify metabolic bottlenecks and determine optimal enzyme expression ratios for subsequent strain engineering in a microbial host (e.g., E. coli or S. cerevisiae).

Principle: By recreating the pathway with purified components, the contribution of each enzyme, substrate, and cofactor can be titrated and analyzed kinetically without interference from cellular regulation or competing metabolic side reactions [2].

Step 1: In Vitro Reconstitution and Steady-State Kinetic Analysis

Protein Expression and Purification:

- Clone genes encoding all enzymes in the target pathway into appropriate expression vectors.

- Overexpress each His-tagged enzyme in E. coli and purify to homogeneity using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) [2].

- Determine protein concentrations and confirm activity for each purified enzyme using established individual enzyme assays.

Defining Reference Conditions:

- Estimate the initial relative protein abundances of the pathway in the native host using quantitative PCR (qPCR) and western blot analysis. Use these levels as a starting reference point for reconstitution [2].

Reconstitution of the Multi-Enzyme System:

- Combine all purified enzyme components in a suitable reaction buffer. Supplement with necessary cofactors (e.g., ATP, NADH/NAD+, NADPH/NADP+, metal ions) [2].

- Initiate the reaction by adding the starting substrate(s).

Systematic Titration and Kinetic Analysis:

- Titrate each enzyme component individually while keeping others constant. Monitor the formation of the final product and any detectable intermediates to identify the impact of each enzyme's concentration on overall pathway flux [2].

- Titrate cofactors and substrates to determine their optimal concentrations and identify any limitations.

- Measure the accumulation of intermediates to pinpoint potential bottleneck steps where a downstream enzyme is rate-limiting.

- Calculate steady-state kinetic parameters for the overall pathway and determine the optimal relative protein concentrations for maximum product yield [2].

Step 2: Rational Design and Pathway Engineering In Vivo

Strain Construction:

- Using the optimal ratios identified in vitro, construct a limited set of engineered microbial strains. This is typically achieved by manipulating plasmid copy numbers, using promoters of varying strengths, or incorporating ribosomal binding site (RBS) libraries to control enzyme expression levels [2].

Metabolic Status Monitoring:

- Analyze the metabolic status of each engineered strain by measuring the accumulation of pathway intermediates. This in vivo data is compared against the optimized profile from the in vitro assays [2].

- Use targeted proteomics to verify that the intended enzyme expression levels have been achieved.

Iterative Engineering:

- Any deviation between the observed in vivo data and the in vitro optimum provides a clear target for the next round of engineering. This iterative process rapidly converges on a high-efficiency cell factory [2].

Example: In Vitro Reconstitution of Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS)

This approach was powerfully demonstrated with the E. coli fatty acid synthase, a system of ten protein components (eight Fab enzymes and the acyl carrier protein, ACP).

- Reconstitution: The entire system was reconstituted using purified components, acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA, and NADPH, resulting in the production of C14-C18 fatty acids [1].

- Key Findings: The in vitro analysis revealed that under conditions of maximum turnover, the dehydratase FabZ was the principal rate-determining component in the E. coli system, whereas a different enzyme, FabH, was rate-limiting in a cyanobacterial FAS [1]. This system also showed how subtle changes in enzyme ratios influence the partitioning between unsaturated and saturated fatty acid products [1].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for a Generic In Vitro Reconstitution

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Role in the Experiment | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Lysate | An inexpensive, single-preparation source of all requisite enzymatic activities, including endogenous support enzymes [3]. | Clarified lysate from engineered E. coli overexpressing pathway enzymes. |

| Purified Enzyme Set | Allows for precise, quantitative control over each catalytic step in the pathway without cellular background [2]. | Homogenously purified FabA-Z enzymes and ACP for FAS reconstitution [1]. |

| Cofactor Regeneration System | Maintains catalytic amounts of expensive cofactors (ATP, NADPH) by using an inexpensive substrate and an auxiliary enzyme or endogenous metabolism [3]. | Endogenous glycolytic enzymes in lysate regenerate ATP from glucose or phosphoenol pyruvate (PEP) [3]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Substrates | Enables precise tracking of metabolic flux, intermediate turnover, and product yield [1]. | Use of 14C-labeled malonyl-CoA to quantify fatty acid synthesis [1]. |

Case Studies in Contemporary Drug Development

The targeted in vitro reconstitution approach has become a critical methodology in the study and engineering of pathways for pharmaceutical compounds.

Case Study 1: Deciphering Cystobactamid Antibiotic Biosynthesis

Challenge: Cystobactamids are promising topoisomerase inhibitors with potent activity against Gram-negative bacteria, but their biosynthesis in the native myxobacterial producer involves unique and obscure steps, particularly the formation of an unusual asparagine linker moiety [6].

In Vitro Reconstitution Approach:

- Heterologous Expression: The entire biosynthetic gene cluster was heterologously expressed in Myxococcus xanthus to establish a production platform [6].

- Targeted In Vitro Experiments: Key steps were then reconstituted in vitro using purified enzymes. This included the stand-alone NRPS module CysH, the oxygenase CysJ, and the O-methyltransferase CysQ [6].

Outcome: The in vitro studies provided direct evidence for the unique biosynthetic logic. They revealed that a bifunctional domain in CysH performs either an aminomutase or a dehydratase reaction depending on the activity of CysJ, and that CysQ only methylates the product in the presence of this bifunctional domain [6]. This detailed mechanistic understanding, gleaned from the purified system, is crucial for engineering novel derivatives.

Case Study 2: Expanding the Chemical Space of Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids

Challenge: Plant natural products (PNPs) like noscapine (an antitussive and potential chemotherapeutic) are often difficult to source, and the range of accessible derivatives for drug development is limited by chemical synthesis [7].

In Vitro & In Silico Strategy:

- Computational Workflow: A cheminformatic workflow (using tools like BNICE.ch and BridgIT) was used to systematically screen the biochemical vicinity of the reconstructed noscapine pathway for pharmaceutically interesting derivatives that were only one enzymatic step away from a pathway intermediate [7].

- Pathway Construction in Yeast: Enzyme candidates for producing these derivatives were predicted and then integrated into yeast strains already engineered with the noscapine pathway.

Outcome: This integrated approach successfully created platform strains for the de novo biosynthesis of (S)-tetrahydropalmatine (a known analgesic and anxiolytic) and three other BIA derivatives, demonstrating the power of combining in silico prediction with in vivo pathway engineering guided by reconstitution principles [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for implementing the modern in vitro reconstitution platform.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Modern In Vitro Reconstitution

| Category | Specific Item | Critical Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Host System | Engineered E. coli BL21(DE3) | Standard workhorse for high-yield protein expression and lysate production; well-understood genetics [3]. |

| Cloning & Expression | Expression Vectors (e.g., pET series); T7 RNA Polymerase | Enables tight, IPTG-inducible control over heterologous enzyme production in the lysate host [3]. |

| Purification | Affinity Chromatography Resins (e.g., Ni-NTA) | Allows rapid, one-step purification of His-tagged recombinant enzymes from lysates [3]. |

| Cofactor Recycling | Phosphoenol Pyruvate (PEP) / Pyruvate Kinase; Glucose | Cost-effective substrate/enzyme pairs for regenerating ATP in vitro, avoiding stoichiometric use [3]. |

| Analytical Tools | HPLC-MS/MS; NMR; Scintillation Counter | For identifying and quantifying novel products, intermediates, and tracking isotope-labeled flux [1] [6] [7]. |

In vitro reconstitution is a powerful biochemical approach that involves isolating a set of enzymatic components from their native cellular environment and recapturing their catalytic activities in a controlled, cell-free system [1]. This methodology allows researchers to apply a diverse array of analytical tools to study the finer details of chemical transformations, including enzymatic reaction mechanisms, kinetics, and the identity of organic product molecules [1]. The concept has existed for over a century, with one of the earliest examples being Eduard Buchner's 1897 experiment where he demonstrated that yeast extracts could ferment sugar into alcohol, proving that cellular machinery rather than the intact cell was responsible for this transformation [1].

With advancements in biotechnology, particularly recombinant DNA technology and heterologous expression systems, researchers can now select specific enzymes of interest, produce them in host cell systems, and obtain analytically pure samples for testing and analysis [1]. For the purpose of scientific rigor, an in vitro reconstituted pathway is typically defined as a series of enzyme-catalyzed chemical reactions where the enzymes catalyze at least four chemical transformations and are obtained as pure components through modern protein purification techniques [1]. This approach has become instrumental in understanding Nature's core biochemical transformations while obeying the fundamental principles of organic chemistry [1].

Conceptual Framework and Core Principles

Theoretical Foundation and Key Requirements

The theoretical foundation of in vitro reconstitution rests on systematically rebuilding biological processes from their minimal components. This bottom-up approach provides unprecedented control over individual variables, allowing researchers to dissect complex biochemical networks [8]. When applied to the study of biological oscillators, for instance, this approach has revealed four fundamental requirements for sustained oscillations: (1) negative feedback to reset the system to its original state, (2) sufficient time-delay in system responses, (3) nonlinearity in reaction kinetics, and (4) balanced timescales between production and degradation [8].

These theoretical principles extend to metabolic pathway reconstitution, where the careful balancing of enzyme ratios, cofactors, and substrates determines the successful emulation of in vivo functionality. The isolation from cellular complexity enables researchers to establish causality between molecular components and emergent system behaviors, a connection often obscured in living systems [8].

Defining Characteristics of Reconstituted Systems

A properly reconstituted pathway exhibits several defining characteristics that distinguish it from crude cellular extracts or partially purified systems. First, the system comprises individually purified protein components with known concentrations and activities. Second, it operates independently of cellular regulation and compartmentalization, though these can be added back systematically to study their effects. Third, it demonstrates functional completeness, capable of converting defined starting substrates to final products through identifiable intermediates. Finally, it exhibits quantifiable kinetics and thermodynamic parameters that can be precisely measured without confounding cellular processes [1] [9].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of In Vitro Reconstituted Pathways

| Characteristic | Description | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Component Purity | Enzymes obtained as pure, discrete entities through chromatographic and other purification methods | SDS-PAGE, mass spectrometry, activity assays |

| Functional Completeness | Capacity to transform starting substrates to final products through all intermediate steps | Product identification and quantification, intermediate tracking |

| Quantifiable Kinetics | Measurable reaction rates, equilibrium constants, and thermodynamic parameters | Enzyme kinetics assays, progress curve analysis |

| Deterministic Composition | Known concentrations of all system components | Protein quantification, stoichiometric calculations |

| Cofactor Dependency | Defined requirements for essential cofactors and energy sources | Cofactor supplementation studies, depletion experiments |

Applications in Biosynthetic Pathway Engineering

Targeted Engineering of Metabolic Pathways

In vitro reconstitution serves as a foundational strategy for targeted engineering of complex biosynthetic pathways in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology [9]. This approach involves systematically reconstituting a targeted biosynthetic pathway in vitro to analyze the contribution of cofactors, substrates, and each enzyme component. The information gained from these controlled experiments then guides subsequent in vivo engineering or de novo pathway assembly for creating high-efficiency cell factories [9].

This methodology addresses a significant barrier in traditional metabolic engineering: the identification of rate-limiting steps for improving specific cellular functions [9]. By studying pathways in isolation from cellular complexity, researchers can precisely determine kinetic bottlenecks, substrate channeling effects, and regulatory constraints that limit pathway flux in living systems. The approach has demonstrated practical application in engineering biosynthesis pathways for chemicals, nutraceuticals, and drug precursors in workhorse organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [9].

Case Studies in Natural Product Biosynthesis

Bacterial Fatty Acid Biosynthesis

The bacterial fatty acid synthase (FAS) system represents a paradigmatic example of in vitro pathway reconstitution [1]. This pathway consists of nine discrete enzymes and an acyl carrier protein (ACP) that work coordinately to construct fatty acids in a repetitive fashion from simple metabolic building blocks derived from acetate [1]. The complete reconstitution of the E. coli fatty acid synthase involved overexpressing all nine Fab enzymes and the ACP, purifying them to homogeneity, and supplementing them with acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA, and NADPH to observe the production of C14-C18 fatty acid species [1].

This reconstitution revealed that under conditions of maximum turnover frequency, the dehydratase FabZ served as the principal rate-determining component, whereas a cyanobacterial FAS was limited by FabH, highlighting how subtle changes in relative activities of individual components can substantially influence product distribution [1]. Beyond mechanistic insights, the reconstituted system provides a cell-free platform for antibacterial discovery and optimizing biofuel production [1].

Isoprenoid Biosynthesis Pathways

Isoprenoids represent another major class of natural products whose biosynthesis has been successfully reconstituted in vitro [1]. These versatile compounds, including cholesterol, steroids, defense agents, and cellular pigments, are constructed from precursors generated by either the mevalonate (MVA) or methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways [1]. The bacterial MVA pathway has been particularly amenable to reconstitution studies, with researchers rerouting it to produce specific isoprenoids like farnesene [1]. These studies have illuminated the remarkable chemical logic underlying isoprenoid diversification while providing platforms for producing valuable therapeutic and nutritional agents such as artemisinin, paclitaxel, and lycopene [1].

Table 2: Representative Biosynthetic Pathways Reconstituted In Vitro

| Pathway | Organism Origin | Key Enzymes | Products | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acid Synthase | E. coli | FabD, FabH, FabG, FabZ, FabB/F, TesA | C14-C18 fatty acids | Biofuel production, antibiotic discovery |

| Mevalonate Pathway | Bacteria | AACT, HMGS, HMGR, MK, PMK, MPD | Isoprenoid precursors | Therapeutic agents, nutraceuticals |

| Polyketide Synthases | Various bacteria | KS, AT, DH, ER, KR, ACP | Complex polyketides | Drug development, biomimetic synthesis |

| Nonribosomal Peptide Synthesis | Fungi/Bacteria | NRPS modules with A, T, C domains | Peptide antibiotics | Pharmaceutical development |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Pathway Selection and Component Identification

The initial stage of in vitro reconstitution involves careful pathway selection and component identification. Researchers must first conduct comprehensive genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses to identify all potential enzymes involved in the target pathway. For bacterial systems, this often begins with gene cluster analysis to identify coordinately regulated genes that may constitute a complete biosynthetic pathway [1]. For less characterized pathways, heterologous expression in model systems like E. coli followed by activity assays can help verify enzyme functions [9].

Enzyme Production and Purification

Once pathway components are identified, the enzyme production and purification phase begins. This typically involves cloning genes into appropriate expression vectors, optimizing expression conditions in host systems (commonly E. coli or yeast), and developing purification protocols for each enzyme. Affinity tags such as His-tags, GST-tags, or MBP-tags are frequently employed to facilitate purification. Critical quality control measures include verifying protein purity via SDS-PAGE, determining concentration through spectrophotometric methods, and confirming enzymatic activity using standardized assays [1].

System Assembly and Optimization

The system assembly and optimization phase represents the core of the reconstitution process. Researchers combine purified enzymes at defined ratios in buffered solutions containing necessary cofactors and substrates. The assembly typically follows a systematic approach:

- Establish individual enzyme activities under the proposed reaction conditions

- Reconstruct partial pathways by combining sequential enzymes

- Integrate complete pathways with all required components

- Optimize component ratios to maximize flux and product yield

- Balance cofactor regeneration systems when required

This systematic assembly helps identify incompatibilities between different enzymatic components and allows for troubleshooting of non-functional pathways [9].

Analytical Methods and Validation

Comprehensive analytical methods and validation are crucial for characterizing reconstituted pathways. Standard methodologies include:

- Chromatographic techniques (HPLC, GC) for separating and quantifying substrates, intermediates, and products

- Mass spectrometry for structural confirmation of pathway products

- Spectrophotometric assays for continuous monitoring of NAD(P)H-dependent reactions

- Radiolabeled tracer studies for tracking carbon flux through pathways

- Kinetic analysis to determine Michaelis-Menten parameters for individual enzymes and overall pathway flux

Successful validation requires demonstrating that the reconstituted pathway produces the expected final product at reasonable yields and recapitulates known in vivo characteristics [1].

Visualization of Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for in vitro pathway reconstitution, from initial gene identification to functional pathway characterization:

In Vitro Reconstitution Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful in vitro reconstitution requires careful selection and preparation of essential research reagents. The following table details critical components and their functions in reconstituted biosynthetic pathways:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pathway Reconstitution

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Reconstituted Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Components | Purified recombinant enzymes (FabA-Z, PKS modules, NRPS complexes) | Catalytic elements that perform biochemical transformations |

| Carrier Proteins | Acyl Carrier Protein (ACP), ArCP, PCP | Covalent tethering of pathway intermediates during synthesis |

| Cofactors | NAD(P)H, ATP, Coenzyme A, SAM | Electron carriers, energy sources, and metabolic activators |

| Substrates | Acetyl-CoA, Malonyl-CoA, Amino Acids | Building blocks for biosynthetic transformations |

| Buffer Components | Tris-HCl, HEPES, Potassium Phosphate | pH maintenance and ionic environment optimization |

| Stabilizers | Glycerol, DTT, EDTA, Mg²⁺ | Protein stability preservation and metal cofactor provision |

Integration with Synthetic Biology

In vitro reconstitution plays a pivotal role in the emerging field of synthetic cell (SynCell) development [10]. The bottom-up assembly of SynCells from molecular components represents the ultimate application of reconstitution methodologies, aiming to create artificial constructs that mimic cellular functions [10]. These endeavors require the integration of diverse functional modules including:

- Genetic circuits for information processing based on transcription-translation (TX-TL) systems assembled from purified components [10]

- Metabolic networks providing energy and building blocks through reconstituted metabolic pathways [10]

- Membrane transport systems for molecular exchange between the SynCell and its environment [10]

- Division machinery capable of facilitating controlled SynCell reproduction [10]

The reconstruction of a functional synthetic central dogma with efficiency and controllability comparable to living systems remains a substantial challenge, with current state-of-the-art systems still far from achieving complete self-replication of all essential cellular components [10].

Technical Considerations and Challenges

Compatibility and Integration Issues

A significant challenge in in vitro reconstitution involves overcoming compatibility issues between diverse biochemical systems developed by different research groups [10]. These incompatibilities can arise from differences in buffer conditions, ionic requirements, temperature optima, or chemical incompatibilities between cofactor systems. The complexity of combining and integrating components scales exponentially with module numbers, requiring sophisticated experimental design and optimization strategies [10].

Spatial Organization and Compartmentalization

Biological pathways in living cells often benefit from spatial organization and compartmentalization that is difficult to recapitulate in vitro. Researchers are addressing this challenge through various strategies including:

- Coacervates as biomolecular condensates that concentrate pathway components [10]

- Lipid vesicles that mimic cellular membranes and enable compartmentalization [10]

- Emulsion droplets that provide microenvironments for specific pathway steps [10]

- DNA-based cytoskeletons that create organizational scaffolds within synthetic cells [10]

Finding the proper "initial conditions" to boot up a bottom-up SynCell remains a fundamental challenge, as there is currently no blueprint guiding the integration of different modules in a spatially ordered manner within a synthetic cellular environment [10].

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

The future of in vitro reconstitution research includes several promising directions. First, the increasing availability of automated biofoundries will accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycles necessary for optimizing complex reconstituted systems [10]. Second, advances in microfluidics and single-cell analysis will enable high-throughput screening of pathway variants under precisely controlled conditions. Third, the integration of non-natural building blocks including synthetic nucleotides, amino acids, and metabolic intermediates will expand the chemical capabilities of reconstituted pathways beyond natural product biosynthesis [10].

As the field progresses, in vitro reconstitution will continue to bridge the gap between theoretical biochemistry and practical pathway engineering, enabling both fundamental discoveries and applied biotechnology innovations across medicine, energy production, and biomanufacturing [9] [10].

Within the broader context of in vitro reconstitution of biosynthetic pathways, the elucidation of the 3-Hydroxypicolinic acid (3-HPA) biosynthesis represents a paradigm-shifting case study. 3-HPA serves as an important pyridine building block for bacterial secondary metabolites and is widely employed as a matrix substance for analyzing oligonucleotides and oligosaccharides via Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-MS) [11] [12]. Although this compound has been utilized for decades in analytical chemistry and is incorporated into antibiotics such as etamycin [13], its biosynthetic origin remained enigmatic until recent pioneering work. This application note details the complete in vitro reconstitution of the 3-HPA biosynthetic pathway, revealing an unusual assembly logic that diverges from previously hypothesized routes and provides a robust platform for engineering novel pyridine-based compounds.

Unconventional Biosynthetic Pathway of 3-HPA

Key Enzymatic Components

The biosynthetic pathway of 3-HPA was successfully reconstituted in vitro, demonstrating that three specific enzymes are required to transform the simple precursor L-lysine into 3-HPA [14] [15]:

- L-lysine 2-aminotransferase: Catalyzes the initial transamination reaction.

- Two-component monooxygenase: Mediates a key hydroxylation step.

- FAD-dependent dehydrogenase: Completes the formation of the aromatic system.

Table 1: Key Enzymes in the 3-HPA Biosynthetic Pathway

| Enzyme | Reaction Catalyzed | Cofactors/Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| L-lysine 2-aminotransferase | Transamination of L-lysine | α-ketoglutarate as amino acceptor |

| Two-component monooxygenase | C-3 hydroxylation of piperideine-2-carboxylic acid | NAD(P)H, O₂ |

| FAD-dependent dehydrogenase | Aromatization to 3-HPA | FAD |

Pathway Logic and Intermediate Flow

Contrary to the expected route of direct C-3 hydroxylation of picolinic acid, the research demonstrated that 3-HPA derives from a successive process involving C-3 hydroxylation of piperideine-2-carboxylic acid followed by tautomerization of the produced 3-hydroxyl dihydropicolinic acid [14]. This unexpected assembly logic reveals nature's strategy for constructing this important heterocyclic scaffold.

Diagram 1: The Unconventional 3-HPA Biosynthetic Pathway from L-Lysine

In Vitro Reconstitution Methodology

Experimental Workflow for Pathway Reconstitution

The complete in vitro reconstitution of the 3-HPA pathway requires careful preparation of enzymatic components and systematic analysis of intermediates and final products.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Pathway Reconstitution

Detailed Protocol: In Vitro Reconstitution of 3-HPA Biosynthesis

Enzyme Preparation

- Cloning and Expression: Clone genes encoding L-lysine 2-aminotransferase, two-component monooxygenase, and FAD-dependent dehydrogenase into appropriate expression vectors (e.g., pET series).

- Protein Purification: Express enzymes in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purify using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography followed by size exclusion chromatography.

- Enzyme Storage: Store purified enzymes in storage buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol) at -80°C until use.

Reaction Setup

Table 2: Standard Reaction Mixture for 3-HPA Biosynthesis

| Component | Final Concentration | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) | 50 mM | Maintains optimal pH |

| L-lysine | 2 mM | Pathway substrate |

| α-ketoglutarate | 1 mM | Amino group acceptor |

| NADPH | 1 mM | Reducing equivalent for monooxygenase |

| FAD | 0.1 mM | Cofactor for dehydrogenase |

| Purified enzyme mixture | 0.5-1 mg/mL each | Optimal enzyme ratio should be determined empirically |

- Assemble the reaction mixture on ice in a total volume of 500 µL.

- Incubate at 30°C for 60-120 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Terminate the reaction by adding 50 µL of 20% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA).

- Remove precipitated protein by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Collect supernatant for analysis.

Analytical Methods

LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Use reversed-phase C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 µm)

- Mobile phase A: 0.1% formic acid in water

- Mobile phase B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

- Gradient: 5-95% B over 15 minutes

- Flow rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Detection: ESI-negative mode with MRM transitions

Critical MRM Transitions:

- 3-HPA: 138.9 → 95.0 (collision energy -20 eV)

- Piperideine-2-carboxylic acid: 128.0 → 110.0 (collision energy -15 eV)

- 3-Hydroxy dihydropicolinic acid: 142.0 → 124.0 (collision energy -18 eV)

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful reconstitution of the 3-HPA biosynthetic pathway requires specific reagents and materials with defined purity standards.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 3-HPA Biosynthesis Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| 3-Hydroxypicolinic acid (standard) | ≥99.0% (HPLC); CAS: 874-24-8 [11] [16] | Analytical standard for method validation |

| L-lysine | Molecular biology grade | Primary substrate in pathway |

| NADPH | ≥95% purity | Cofactor for monooxygenase component |

| FAD | ≥95% purity | Essential cofactor for dehydrogenase |

| α-ketoglutarate | Cell culture tested | Amino group acceptor for transaminase |

| MALDI-MS matrix | 3-HPA, high purity [17] | Analytical verification of oligonucleotide applications |

| Expression system | pET vectors, E. coli BL21(DE3) | Enzyme production for pathway reconstitution |

Applications and Implications

Analytical Chemistry Applications

The discovery of 3-HPA's biosynthetic route has significant implications for its primary application as a MALDI matrix. 3-HPA is particularly valued for oligonucleotide analysis due to its strong UV absorption and ability to form homogeneous crystals with analytes [12]. The compound's structural properties, revealed through its biosynthesis, explain its exceptional performance in:

- Oligonucleotide Quantification: Enables accurate allele frequency determination in pooled DNA samples with detection limits as low as 2% minor allele frequency [12].

- Non-invasive Prenatal Diagnosis: Facilitates detection of fetal point mutations in maternal plasma where fetal DNA constitutes only 3-6% of total DNA [12].

- RNA Modification Analysis: Serves as matrix in RNase T1 digestion protocols for identifying post-transcriptional modifications [12].

Metabolic Engineering Potential

The elucidated pathway opens new avenues for engineered biosynthesis of novel pyridine-based building blocks. The unusual assembly logic, bypassing picolinic acid as an intermediate, suggests potential for:

- Pathway Engineering: Creating analogs through precursor-directed biosynthesis or enzyme engineering.

- Combinatorial Biosynthesis: Combining 3-HPA pathway enzymes with other natural product biosynthetic systems.

- Enzyme Mechanistic Studies: Investigating the unique two-component monooxygenase and FAD-dependent dehydrogenase mechanisms.

The in vitro reconstitution approach demonstrated for 3-HPA provides a template for elucidating other obscure biosynthetic pathways in microbial systems, advancing our fundamental understanding of natural product assembly and expanding the toolbox for synthetic biology and drug development.

The in vitro reconstitution of biosynthetic pathways represents a cornerstone of modern metabolic engineering and natural product research. This approach allows researchers to elucidate complex biochemical networks, identify novel enzymes, and establish platforms for the sustainable production of valuable compounds. Within this field, comparative genomic analysis has emerged as a powerful discovery tool, enabling scientists to identify candidate genes involved in specialized metabolism by examining genomic correlations across diverse organisms.

This Application Note details how comparative genomics facilitated the elucidation of the complete biosynthetic pathway for di-myo-inositol-1,1′-phosphate (DIP), a unique compatible solute found in hyperthermophilic archaea and bacteria. We present a detailed experimental protocol for the in vitro reconstitution of DIP biosynthesis, providing a framework for researchers investigating similar pathways in other systems.

Background: DIP as a Key Thermo- and Osmoprotectant

Di-myo-inositol-1,1′-phosphate (DIP) is an unusual inositol derivative that functions as a vital compatible solute in hyperthermophilic microorganisms. It was first identified in Pyrococcus woesei [18] and has since been found in other archaea such as Pyrococcus furiosus, Methanococcus igneus, and certain eubacteria of the order Thermotogales [19].

The intracellular concentration of DIP demonstrates a direct correlation with external stress factors. Studies reveal that DIP accumulation increases in response to both elevated extracellular NaCl concentrations and supraoptimal growth temperatures, suggesting its dual role as both an osmoprotectant and a thermostabilizer [19]. In vitro experiments have confirmed that the potassium salt of DIP provides exceptional stabilization for enzymes like glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase at temperatures exceeding 100°C [19].

Pathway Elucidation Through Comparative Genomics

Genomic Insights and Pathway Prediction

The initial discovery of the DIP biosynthetic pathway was guided by genomic analyses and logical biochemical reasoning. Researchers recognized that the sole known pathway for inositol biosynthesis in all organisms involves the conversion of D-glucose-6-phosphate to myo-inositol, suggesting that DIP synthesis would likely utilize myo-inositol and its phosphorylated derivatives as precursors [19].

Based on this understanding, a four-step biosynthetic pathway was proposed:

- Synthesis of L-myo-inositol 1-phosphate from glucose-6-phosphate

- Dephosphorylation to free myo-inositol

- Activation of inositol phosphate with CTP

- Coupling of activated inositol with a second inositol molecule to form DIP

This predicted pathway was subsequently validated through in vitro enzymatic assays and isotopic labeling studies [19] [18].

Key Enzymes in the DIP Biosynthetic Pathway

Table 1: Enzymatic Components of the DIP Biosynthetic Pathway

| Step | Enzyme | Reaction Catalyzed | Cofactors/Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L-myo-inositol 1-phosphate synthase (I-1-P synthase) | Converts D-glucose 6-phosphate to 1D-myo-inositol 3-phosphate | NAD+ [20] |

| 2 | Inositol 1-phosphate phosphatase (I-1-P phosphatase) | Dephosphorylates I-1-P to free myo-inositol | - |

| 3 | CTP:I-1-P cytidylyltransferase | Activates I-1-P with CTP to form CDP-inositol | CTP [19] |

| 4 | DIP synthase | Couples CDP-inositol with myo-inositol to form DIP | - |

Experimental Protocol: In Vitro Reconstitution of DIP Biosynthesis

Preparation of Cell-Free Extracts

Cell Culture and Harvesting: Grow M. igneus or P. woesei cultures under optimal conditions (85°C for M. igneus, 95°C for P. woesei) under an H₂-CO₂ (4:1) atmosphere [19] [18]. Harvest cells during mid-exponential growth phase (OD₆₆₀ ≈ 0.6) via centrifugation at 9,000 × g for 30 minutes.

Cell Lysis: Resuspend cell pellet (1 g wet weight) in 10 mL of standard buffer (50 mM Tris acetate, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 8.0). Lyse cells using:

Protein Fractionation: Centrifuge lysate at 9,000 × g for 20 minutes to remove debris. Perform ammonium sulfate precipitation:

- Add solid ammonium sulfate to 44% saturation, incubate 20 minutes, centrifuge at 17,000 × g.

- Add ammonium sulfate to supernatant to 85% saturation, collect precipitate.

- Dialyze fractions overnight against standard buffer at 4°C.

Enzyme Activity Assays

I-1-P Synthase Activity

Principle: Monitor conversion of D-glucose-6-phosphate to I-1-P.

Method A - ³¹P NMR Spectroscopy:

- Reaction mixture: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 10 mM D-glucose-6-phosphate, 1 mM NAD⁺, dialyzed protein extract

- Incubate at 85°C for 2 hours

- Terminate reaction by heating to 100°C for 5 minutes

- Analyze by ³¹P NMR for I-1-P formation [19]

Method B - Colorimetric Inorganic Phosphate Assay:

- Use same reaction conditions as above

- Terminate reaction with ice-cold trichloroacetic acid (10% final concentration)

- Measure liberated inorganic phosphate colorimetrically at 660 nm [19]

I-1-P Phosphatase Activity

Principle: Measure dephosphorylation of I-1-P to free inositol.

- Reaction mixture: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 10 mM I-1-P, dialyzed protein extract

- Incubate at 85°C for 2 hours

- Terminate reaction and measure inorganic phosphate as above [19]

DIP Synthase Activity

Principle: Detect DIP formation from CDP-inositol and myo-inositol.

- Reaction mixture: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 5 mM CDP-inositol (chemically synthesized), 5 mM myo-inositol, dialyzed protein extract

- Incubate at 85°C for 2 hours under anaerobic conditions

- Analyze reaction products by ¹H NMR or TLC [19]

Verification via ¹³C Labeling Studies

In Vivo Labeling: Grow M. igneus cultures with multiple injections of [2,3-¹³C]pyruvate or [3-¹³C]pyruvate during exponential growth phase [19].

DIP Isolation and Analysis:

- Prepare ethanol extracts from labeled cells

- Purify DIP via QAE-Sephadex column chromatography

- Analyze label distribution in DIP using ¹³C NMR spectroscopy

- Confirm labeling patterns consistent with glucose-6-phosphate precursor scrambled via pentose phosphate pathway transketolase and transaldolase activities [19]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for DIP Pathway Reconstitution

| Reagent | Specifications | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| D-Glucose-6-phosphate | Disodium salt, high purity | Substrate for I-1-P synthase [19] |

| I-1-P | Cyclohexylammonium salt, ≥73% pure (1-phosphate isomer) | Substrate for phosphatase and cytidylyltransferase [19] |

| CDP-inositol | Chemically synthesized from CMP-morpholidate and I-1-P trioctylamine salt | Activated inositol donor for DIP synthase [19] |

| NAD+ | High-purity grade | Cofactor for I-1-P synthase [20] |

| CTP | Nucleotide triphosphate, high purity | Substrate for cytidylyltransferase [19] |

| [²³C]pyruvate | 99% ¹³C enrichment, sodium salts | Isotopic tracer for pathway verification [19] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Expected Results and Troubleshooting

- Successful I-1-P synthase activity should yield approximately 0.1-0.5 µmol I-1-P per mg protein per hour at 85°C [19].

- DIP synthase activity in P. woesei extracts typically generates ~0.5 µmol DIP per hour per mg protein when provided with CDP-inositol and myo-inositol [18].

- Critical negative control: Omit CDP-inositol from DIP synthase reactions to confirm dependence on activated intermediate.

- Potential pitfall: CDP-inositol preparation may contain isomers; characterize by ¹H-¹H TOCSY NMR before use [19].

Pathway Visualization

Workflow Diagram

Applications and Future Directions

The successful elucidation and in vitro reconstitution of the DIP biosynthetic pathway enables several advanced applications:

- Metabolic Engineering: Implementation of DIP biosynthesis in industrial microorganisms for enhanced thermotolerance.

- Enzyme Mechanism Studies: Detailed kinetic and structural analysis of the novel cytidylyltransferase and DIP synthase enzymes.

- Biotechnological Applications: Potential use of DIP as a natural stabilizer for enzymes and vaccines requiring elevated temperature storage.

This protocol demonstrates the power of combining comparative genomics with systematic in vitro reconstitution for elucidating complete biosynthetic pathways, providing a template for investigating other complex metabolic systems in extremophilic organisms.

Biomimetic organic synthesis strategically transposes the efficient chemistry of nature into the laboratory, using biosynthetic pathways as blueprints for devising synthetic routes to complex natural products [21]. This approach is grounded in the principle that natural products, assembled from simple building blocks by enzymes, obey fundamental rules of organic chemistry, often achieving remarkable regio- and stereospecificity [1]. The logic of biosynthesis can inspire the design of abiotic synthetic routes that mirror the efficiency and elegance of nature's own processes [1].

The in vitro reconstitution of biosynthetic pathways provides the critical experimental foundation for biomimetic synthesis. By isolating enzymatic pathways from their native cellular environments and studying them in a controlled, cell-free system, researchers can capture fine details of enzymatic mechanisms, kinetics, and intermediate structures [1]. This deep understanding of nature's synthetic strategies directly fuels the development of novel biomimetic chemistries. For instance, early studies of fermentation in yeast extracts validated that cellular machinery alone was responsible for converting sugars to alcohol, paving the way for the detailed mechanistic understanding of glycolysis and ATP's role in driving biochemical processes [1]. Today, with advanced recombinant DNA and protein purification technologies, scientists can reconstitute virtually any enzymatic pathway of interest, obtaining pure components for detailed analysis and inspiration [1].

Application Note: In Vitro Reconstitution as a Discovery Tool

Rationale and Workflow

In vitro reconstitution serves as a powerful platform for deconstructing biological complexity and gaining unambiguous insight into enzymatic catalysis. It allows for the precise control of reaction conditions, the exclusion of interfering cellular activities, and the direct characterization of reactive intermediates and products [1]. The fundamental workflow involves excising a complete enzymatic pathway from its native host, heterologously expressing and purifying its constitutive enzymes, and then systematically combining them with substrates and cofactors to recapitulate the entire biosynthetic sequence in a test tube [9]. The information gleaned from these studies—particularly the identity of intermediates and the order of chemical transformations—provides direct inspiration for designing biomimetic synthetic routes that replicate nature's strategic logic.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated research cycle connecting in vitro reconstitution to biomimetic synthesis:

Case Study: Bacterial Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS)

The bacterial fatty acid synthase is a prototypical system whose in vitro reconstitution has illuminated a core biosynthetic mechanism for carbon-carbon bond formation. This pathway constructs aliphatic chains through an iterative cycle of decarboxylative Claisen condensations and β-carbon processing [1].

- Pathway Overview: The E. coli FAS comprises nine discrete enzymes and an acyl carrier protein (ACP). The pathway is initiated by FabD, which transfers a malonyl group from malonyl-CoA to the phosphopantetheine arm of ACP. FabH then catalyzes a decarboxylative condensation between malonyl-ACP and acetyl-CoA to form acetoacetyl-ACP. This intermediate then undergoes reduction (FabG), dehydration (FabZ/FabA), and a second reduction to yield a saturated acyl-ACP. This extension cycle repeats, with ketosynthases FabB or FabF adding two-carbon units from malonyl-ACP, until a full-length (C14-C18) chain is produced [1].

- Key Chemical Logic: The decarboxylative Claisen condensation is a central manifold for C-C bond formation in nature. The ketosynthase enzymes (FabH, FabB, FabF) employ an active-site cysteine thiol to carry the growing acyl chain as a thioester and to catalyze the nucleophilic attack by the enolate derived from malonyl-ACP [1].

- In Vitro Insights: The complete in vitro reconstitution of the E. coli FAS using ten purified protein components revealed that the dehydratase FabZ is the principal rate-determining enzyme, a finding that was not apparent from studying individual enzymes in isolation [1]. This systems-level understanding is crucial for applications in metabolic engineering and biofuel production.

Experimental Protocol: In Vitro Reconstitution of a Multi-Enzyme Pathway

This protocol outlines the general methodology for reconstituting a biosynthetic pathway in vitro, based on established procedures [1] [9].

1. Pathway Selection and Gene Identification

- Identify the target natural product and its hypothesized biosynthetic pathway using genomic and metabolomic data.

- Identify the genes encoding the requisite enzymes from databases like KEGG [22] or MetaCyc [22].

2. Heterologous Expression and Purification

- Clone the identified genes into appropriate expression vectors (e.g., pET vectors for E. coli).

- Transform the vectors into a suitable expression host (e.g., E. coli BL21(DE3)).

- Grow cultures to mid-log phase and induce protein expression with IPTG.

- Purify each enzyme to homogeneity using affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag purification), followed by size-exclusion or ion-exchange chromatography if necessary. Confirm purity via SDS-PAGE.

3. In Vitro Reconstitution Assay

- Reaction Setup: Combine the following components in a suitable buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl or phosphate buffer, pH 7.5-8.0):

- Purified enzymes (each at 1-10 µM, depending on specific activity)

- Substrates (e.g., acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA)

- Cofactors (e.g., NADPH)

- MgCl₂ or other essential metal ions

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at the optimal temperature for the pathway (e.g., 30-37°C for bacterial systems) for a defined period (minutes to hours).

- Termination: Quench the reaction by adding an organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile or methanol) or by heat inactivation.

4. Analysis and Product Characterization

- Analyze the reaction mixture using LC-MS or GC-MS to detect and identify intermediates and final products.

- Compare retention times and mass spectra with authentic standards when available.

- Use UV-spectrophotometry to monitor cofactor consumption (e.g., NADPH oxidation at 340 nm) for kinetic analyses [1].

Protocol: Computational Navigation of Biosynthetic Pathways

For many natural products, the complete biosynthetic pathway is unknown. Computational tools like BioNavi-NP have been developed to predict plausible biosynthetic routes from simple building blocks to complex targets, providing a starting hypothesis for both in vitro reconstitution and biomimetic synthesis [23]. BioNavi-NP uses a deep learning model trained on biochemical and organic reactions to perform single-step retrosynthetic predictions, which are then assembled into multi-step pathways using an AND-OR tree-based search algorithm [23].

Step-by-Step Protocol for BioNavi-NP

1. Input Preparation

- Obtain the SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) string of the target natural product from databases like PubChem [22] or ZINC [22].

2. Pathway Prediction

- Access the BioNavi-NP web server (http://biopathnavi.qmclab.com/).

- Input the target SMILES string.

- Configure search parameters (e.g., maximum number of steps, organism-specific enzyme preference).

- Run the prediction algorithm.

3. Results Analysis

- Review the predicted pathways, which are ranked by a computed cost score.

- Examine each proposed biosynthetic step and the predicted enzyme class (e.g., ketosynthase, methyltransferase).

- For critical steps, use enzyme prediction tools like Selenzyme [23] to suggest specific enzyme sequences.

4. Experimental Validation

- Use the top-ranked predicted pathways as a guide for in vitro reconstitution experiments.

- Clone and express the candidate enzymes identified or suggested by the tool.

- Follow the in vitro reconstitution protocol (Section 2.3) to validate the proposed pathway.

The following workflow integrates computational prediction with experimental validation:

Data Presentation and Research Tools

Quantitative Comparison of Biocatalytic Strategies

Table 1: Performance of Computational Biosynthetic Pathway Prediction Tools

| Tool/Method | Approach | Single-Step Top-10 Accuracy | Multi-Step Pathway Recovery Rate | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioNavi-NP [23] | Deep Learning (Transformer) | 60.6% | 90.2% (pathway found) / 72.8% (building blocks correct) | High accuracy and generalization; rule-free |

| RetroPathRL [23] | Rule-based/Reinforcement Learning | ~42.1% (estimated from text) | Not specified | Built upon known biochemical reaction rules |

| Knowledge-Based Methods [23] | Database Mining & Similarity | Not Applicable (database-dependent) | Low for novel compounds | Relies on curated, known pathways |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for In Vitro Reconstitution and Biomimetic Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Acyl Carrier Protein (ACP) [1] | A central carrier protein in FAS and PKS; activated by phosphopantetheinylation to carry growing acyl chains as thioesters. | Essential for in vitro studies of fatty acid and polyketide biosynthesis. |

| Coenzyme A (CoA) Derivatives (Acetyl-CoA, Malonyl-CoA) [1] | Activated acyl group donors; serve as fundamental building blocks for chain elongation in FAS, PKS, and other pathways. | Substrates for initiating and elongating polyketide and fatty acid chains in vitro. |

| Nicotinamide Cofactors (NADPH, NADH) [1] | Redox cofactors essential for reductive steps in biosynthetic pathways (e.g., ketoreduction in FAS). | Required for enzymatic steps catalyzed by ketoreductases (FabG) and enoyl reductases. |

| BioNavi-NP Web Toolkit [23] | A deep learning-based tool for predicting biosynthetic pathways of natural products. | Generating testable hypotheses for the biosynthesis of compounds with unknown pathways. |

| BRENDA / KEGG Databases [22] | Comprehensive databases of enzymes, reactions, and metabolic pathways. | Identifying enzyme sequences, catalytic mechanisms, and pathway context. |

| Heterologous Expression System (E.g., E. coli with pET vectors) [1] | A host system for the high-yield production of recombinant biosynthetic enzymes. | Overexpression and purification of individual pathway enzymes for in vitro studies. |

The synergy between in vitro reconstitution and biomimetic synthesis creates a powerful feedback loop for advancing organic chemistry. In vitro studies provide an unambiguous, detailed view of nature's synthetic machinery, revealing the remarkable organic chemistry performed by enzymes. This knowledge, in turn, inspires the development of innovative, efficient, and elegant biomimetic synthetic routes in the laboratory. As computational tools like BioNavi-NP continue to improve, they will further accelerate the elucidation of complex biosynthetic pathways, ensuring a growing wellspring of inspiration for synthetic chemists and deepening our understanding of nature's chemical logic.

Building and Applying Pathways: Cell-Free Platforms and Industrial Translation

The In vitro Prototyping and Rapid Optimization of Biosynthetic Enzymes (iPROBE) platform represents a transformative approach in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. This platform addresses a critical bottleneck in cellular metabolic engineering: the slow and laborious process of designing, building, and optimizing biosynthetic pathways within living cells. Traditional methods are hampered by cellular transformation idiosyncrasies, limited genetic parts, and the absence of high-throughput workflows, often extending development timelines to 6-12 months [24]. iPROBE overcomes these limitations by leveraging cell-free protein synthesis and metabolic pathway assembly to accelerate the design-build-test cycles essential for developing sustainable biomanufacturing processes [25].

By decoupling pathway prototyping from cellular constraints, iPROBE provides a rapid and powerful framework for identifying optimal enzyme combinations. This capability is crucial for advancing the bioeconomy, enabling the production of low-cost biofuels, bioproducts, medicines, and materials from sustainable resources [24]. The platform demonstrated its efficacy by completing pathway optimization in approximately two weeks, a task that traditionally required nearly a year [24]. This remarkable acceleration stands to significantly impact diverse industries, from clean energy to consumer products, by bringing sustainable chemical manufacturing to scale more efficiently.

Core iPROBE Methodology

The iPROBE methodology centers on utilizing cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) to produce biosynthetic enzymes, which are then assembled into functional metabolic pathways in a controlled, cell-free environment. The core process involves several key stages:

- Lysate Preparation: Cellular lysates are derived from host organisms and serve as the foundational chassis. These lysates contain the essential transcriptional and translational machinery required for protein synthesis but lack the regulatory constraints of intact cells.

- Enzyme Expression: Biosynthetic enzymes are produced directly within the cell-free lysates via CFPS. This step bypasses the need for cloning and transformation into living hosts.

- Pathway Assembly: Defined combinations of enzyme-enriched lysates are mixed to construct complete biosynthetic pathways. This "mix-and-match" approach allows for rapid testing of numerous enzyme variants and pathway configurations [25].

- Performance Analysis: The assembled pathways are evaluated for metabolic flux and product yield. The cell-free environment facilitates direct sampling and quantification of intermediates and final products.

This integrated approach allows researchers to prototype pathways in vitro before committing to more time-consuming cellular implementation, ensuring that only the most promising designs are advanced for in vivo testing.

Key Advantages Over Cellular Systems

The iPROBE platform offers several distinct advantages that make it particularly suited for rapid metabolic pathway engineering:

- Direct Control over Reaction Conditions: The open nature of the cell-free system allows for precise manipulation of cofactors, substrates, and other environmental factors that influence pathway performance.

- Elimination of Cellular Complexity: By removing cellular barriers (membranes) and regulatory networks (gene regulation, metabolic cross-talk), iPROBE provides a more direct and interpretable assessment of pathway function.

- High-Throughput Capability: The system is inherently scalable and compatible with multi-well plate formats, enabling the parallel testing of hundreds of pathway variants. This was demonstrated through the screening of 54 different cell-free pathways for 3-hydroxybutyrate production and the optimization of a six-step butanol pathway across 205 permutations [25].

- Predictive Power for Cellular Performance: A strong correlation (r = 0.79) was observed between pathway performance in the iPROBE system and in living microbial cells, validating its use as a predictive prototyping tool [25].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Cell-Free Pathway Prototyping for 3-Hydroxybutyrate (3-HB) Production

This protocol details the screening of biosynthetic pathways for 3-HB production, a valuable chemical precursor, using the iPROBE platform.

Materials and Reagents

- Cell-Free Protein Synthesis System: E. coli or other organism-derived lysate, energy system (creatine phosphate/creatine kinase or phosphoenolpyruvate/pyruvate kinase), amino acid mixture, nucleotides.

- DNA Templates: Plasmid DNA or linear expression constructs encoding biosynthetic enzymes for the target pathway.

- Substrate Solution: Acetyl-CoA or precursor molecules specific to the 3-HB pathway, prepared in appropriate buffer.

- Analytical Standards: Pure 3-HB for HPLC or GC-MS calibration.

- Reaction Vessels: 1.5-2.0 mL microcentrifuge tubes or 96-well deep-well plates.

Procedure

- Lysate Preparation: Prepare cell lysates from the chosen host organism (e.g., E. coli or Clostridium) using established methods such as sonication or French press, followed by centrifugation to remove cell debris. Aliquot and store lysates at -80°C.

- Enzyme Expression: In separate reactions, use the CFPS system to individually express each biosynthetic enzyme required for the 3-HB pathway. Incubate reactions for 4-6 hours at 30-37°C with shaking.

- Pathway Assembly: Combine the CFPS reactions containing individual enzymes in specific ratios to construct the full 3-HB biosynthetic pathway. Include necessary cofactors (e.g., NADPH, ATP).

- Substrate Initiation: Start the metabolic reaction by adding the primary substrate (e.g., Acetyl-CoA) to the assembled pathway mixture.

- Incubation and Sampling: Incubate the reaction at 30°C. Periodically withdraw aliquots (e.g., at 0, 30, 60, 120 minutes) and quench the reaction immediately by acidification or heat inactivation.

- Product Quantification: Analyze quenched samples using HPLC or GC-MS to quantify 3-HB production. Compare against a standard curve for absolute quantification.

Data Analysis

Calculate the rate of 3-HB production (mM/h) and total titer (mM or g/L) for each pathway variant. Normalize data to protein concentration in the CFPS reactions if comparing expression levels across variants.

Protocol: Data-Driven Optimization of a Multi-Step Butanol Pathway

This protocol describes the application of iPROBE and data-driven design to optimize a complex, six-step biosynthetic pathway for butanol production.

Materials and Reagents

- Enzyme Library: DNA templates for multiple homologs or engineered variants for each of the six enzymatic steps in the butanol pathway (e.g., Thl, Hbd, Crt, Ter, AdhE).

- iPROBE Reaction Mixture: Standardized cell-free lysate, energy regeneration system, amino acids, cofactors (NAD+, NADPH, Ferredoxin).

- Substrate: Glucose or Butyryl-CoA, depending on the pathway segment being optimized.

- Analytical Equipment: GC-FID or HPLC for butanol and intermediate quantification.

Procedure

- Design of Experiment (DOE): Define the experimental space. For a six-step pathway with 3-5 enzyme variants per step, this can generate hundreds of potential combinations (e.g., 205 were tested in the original study [25]). Use statistical design software to select a representative subset for initial screening if a full factorial design is too large.

- High-Throughput Assembly: In a 96-well plate format, assemble the iPROBE reactions for each pathway permutation. This can be automated using liquid handling robots.

- Parallelized Cell-Free Reactions: Incubate all plates simultaneously under controlled temperature (e.g., 30°C) with shaking.

- Time-Point Sampling: Use a plate reader for in-line monitoring or quench samples at multiple time points for end-point analysis.

- Metabolite Profiling: Quantify butanol and key pathway intermediates (e.g., butyraldehyde) using GC or LC-MS to understand flux distribution and identify potential bottlenecks.

Data Analysis and Model Building

- Performance Metrics: Calculate final butanol titer (g/L), yield (mol/mol substrate), and productivity (g/L/h).

- Correlation Analysis: Identify enzyme variants or combinations that correlate with high butanol production.

- Predictive Modeling: Use machine learning or multivariate regression to build a model that predicts pathway performance based on enzyme combination. This model can then guide the selection of further variants for iterative optimization cycles.

Quantitative Performance Data

The iPROBE platform's effectiveness is demonstrated by significant quantitative improvements in both prototyping speed and final product yields.

Table 1: Summary of iPROBE Screening and Optimization Results

| Pathway | Scale of Experiment | Key Outcome | Traditional Timeline | iPROBE Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Hydroxybutyrate | 54 pathway variants screened | Identification of high-performing enzyme combinations | Several months | ~2 weeks [24] |

| Butanol (6-step) | 205 pathway permutations tested | Data-driven optimization of flux | 6-12 months [24] | ~2 weeks [24] |

Table 2: Validation Metrics: Correlation between iPROBE and Cellular Performance

| Metric | iPROBE Result | In Vivo Result | Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Performance Correlation | N/A | N/A | r = 0.79 [25] |

| 3-HB Production in Clostridium | Predictive data from cell-free | 14.63 ± 0.48 g L⁻¹ [25] | N/A |

| Fold Improvement | N/A | 20-fold increase [25] | N/A |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the iPROBE platform relies on a set of core reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPROBE Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lysate | Provides the fundamental machinery for transcription, translation, and energy metabolism. | Choice of host organism (e.g., E. coli, Clostridium) is critical; preparation method affects yield and activity. |

| Energy Regeneration System | Replenishes ATP and other high-energy phosphates consumed during protein synthesis and metabolism. | Common systems: Creatine Phosphate/Creatine Kinase; Phosphoenolpyruvate/Pyruvate Kinase. |

| DNA Templates | Encodes the biosynthetic enzymes to be expressed and tested. | Can be plasmid DNA or linear templates; purity and concentration are vital for efficient CFPS. |

| Cofactor Mixture | Supplies essential enzymatic cofactors (e.g., NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H, Coenzyme A, FAD). | Required to support the activity of a wide range of oxidoreductases and transferases in pathways. |

| Amino Acid Mixture | Building blocks for cell-free protein synthesis. | All 20 canonical amino acids must be present in sufficient concentrations for efficient translation. |

| Analytical Standards | Enables accurate identification and quantification of metabolic products and intermediates. | Pure chemical standards are necessary for calibrating HPLC, GC-MS, or other analytical instruments. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language and adhering to the specified color palette, illustrate the core iPROBE workflow and an example metabolic pathway.

iPROBE Platform Workflow

Example: 3-HB Biosynthetic Pathway

The in vitro reconstitution of biosynthetic pathways represents a powerful paradigm shift in synthetic biology, enabling the production of complex biomolecules outside the constraints of living cells. This approach accelerates the design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycles crucial for engineering therapeutics, valuable natural products, and functional proteins. By decoupling production from cell viability, it allows for precise control over reaction conditions, the synthesis of toxic compounds, and the rapid assembly of multi-enzyme pathways. This application note details two foundational methodologies—a machine learning-accelerated workflow for Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) and a mix-and-match strategy for glycosyltransferase assembly—providing researchers and drug development professionals with detailed protocols to implement these technologies in their own laboratories for the efficient production and optimization of biomolecules.

Machine Learning-Optimized Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS)

Cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) harnesses the transcriptional and translational machinery of cells in a controlled in vitro environment. It offers significant advantages for the rapid production of proteins, including those that are toxic to cells or require intricate post-translational modifications [26]. A key challenge, however, lies in optimizing the composition of the cell-free reaction mixture, which contains numerous components such as cell extract, DNA templates, amino acids, and energy sources. Exploring the vast combinatorial space of component concentrations is a traditionally slow and resource-intensive process.

1.1 Automated and AI-Driven Optimization Workflow

Recent advances have integrated active learning (AL), an artificial intelligence (AI) strategy, with fully automated liquid handling to dramatically accelerate the optimization of CFPS systems. The core principle involves an iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle where an AL model selects the most informative and diverse experimental conditions to test in each round, thereby converging on an optimal composition with a minimal number of experiments [27].

The following diagram illustrates this automated, AI-driven workflow for optimizing CFPS.

1.2 Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Setting Up an Automated CFPS DBTL Cycle

Design Phase:

- Objective: Use an Active Learning model to select the next set of conditions to test.

- Procedure:

- Initialization: Provide the AL model with the list of CFPS components to optimize (e.g., concentrations of Mg2+, K+, cell extract, energy sources) and their feasible ranges.

- Candidate Selection: The AL model (e.g., using a Cluster Margin strategy) selects a batch of conditions that are both highly uncertain (informative for the model) and diverse from each other to avoid redundancy [27].

- Automated Code Generation: The experimental design, including microplate layouts and liquid handling instructions, can be generated automatically using large language models like ChatGPT-4, which has been shown to produce executable code without manual revision [27] [28].

Build Phase:

- Objective: Accurately and efficiently assemble the CFPS reactions as per the design.

- Procedure:

- Employ an Automated Liquid Handler: Use a non-contact dispenser like the I.DOT Liquid Handler. This technology enables high-throughput, precise nanoliter-range dispensing of reagents, minimizing volumes and costs while ensuring reproducibility [29].

- Reagent Assembly: Program the liquid handler to dispense the variable components (from the Design phase) and constant master mix components into a microplate according to the generated layout.

Test Phase:

- Objective: Quantify the protein yield from each reaction condition.

- Procedure:

- Incubation: Incubate the assay plate under optimal temperature and duration for the CFPS system (e.g., 30-37°C for several hours).

- Quantification: Measure the output. For colored or fluorescent proteins (e.g., sfGFP), use a microplate reader. For other proteins, use SDS-PAGE, western blot, or activity assays. In the referenced study, antimicrobial activity assays confirmed the functionality of the produced colicins [27].

Learn Phase:

- Objective: Update the AL model with new results to improve subsequent predictions.

- Procedure:

- Data Integration: Feed the measured protein yields (from the Test phase) back to the AL model, pairing each tested condition with its outcome.

- Model Retraining: Retrain the AL model on the expanded dataset. The model learns the complex relationships between component concentrations and protein yield, improving its ability to predict high-performing conditions.

1.3 Quantitative Outcomes of AI-Optimized CFPS

The application of this AI-driven workflow has demonstrated significant improvements in protein production efficiency. The table below summarizes key results from a recent study.

Table 1: Performance of AI-optimized CFPS for antimicrobial protein production [27].

| Target Protein | CFPS System | Optimization Cycles | Fold Increase in Yield | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colicin M | E. coli extract | 4 | ~2 to 9-fold | Fully functional antimicrobial activity |

| Colicin E1 | E. coli extract | 4 | ~2 to 9-fold | Fully functional antimicrobial activity |

| Colicin M | HeLa cell extract | 4 | ~2 to 9-fold | Fully functional antimicrobial activity |

| Colicin E1 | HeLa cell extract | 4 | ~2 to 9-fold | Fully functional antimicrobial activity |

Mix-and-Match Assembly of Glycosyltransferases

Glycosylation, catalyzed by glycosyltransferases (GTs), is a critical modification that enhances the solubility, stability, and bioactivity of many natural products and therapeutic proteins. However, the narrow substrate specificity of wild-type GTs often limits their application in synthesizing novel glycosylated compounds. A "mix-and-match" domain-swapping strategy provides a solution by engineering chimeric enzymes with tailored or broadened catalytic properties [30].

2.1 Conceptual Workflow for GT Domain Assembly

This strategy exploits the modular structure of enzymes from the GT-B family, which typically consist of two distinct Rossman-fold domains: one for binding the sugar donor and another for binding the acceptor substrate. By swapping these domains between different parent GTs, it is possible to create new chimeric enzymes with hybrid functionalities.

The logical flow for creating and testing these chimeric glycosyltransferases is outlined below.

2.2 Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 2: Creating and Screening a Chimeric Glycosyltransferase Library

Design and Build Phases:

- Objective: Create a library of chimeric GT genes by swapping donor and acceptor domains between two or more parent GT-B enzymes.

- Procedure:

- Gene Identification: Clone the full-length genes of the parent GTs (e.g., GT-A and GT-B).

- Domain Definition: Based on sequence alignment and structural data, define the boundaries of the N-terminal (often acceptor domain) and C-terminal (often donor domain) Rossman folds.