Divergent Pathways: Unlocking Nature's Biosynthetic Strategies for Modern Drug Synthesis

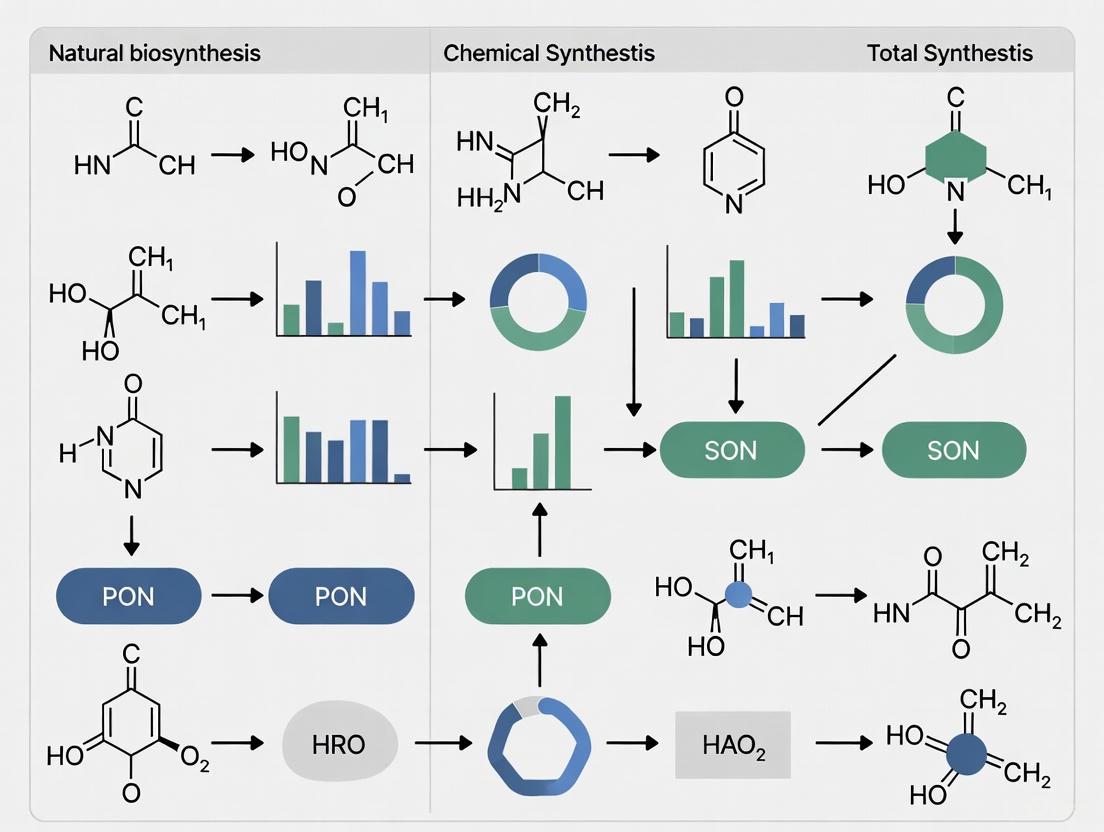

This article explores the parallel and increasingly convergent strategies employed by nature and synthetic chemists in the total synthesis of complex molecules.

Divergent Pathways: Unlocking Nature's Biosynthetic Strategies for Modern Drug Synthesis

Abstract

This article explores the parallel and increasingly convergent strategies employed by nature and synthetic chemists in the total synthesis of complex molecules. It delves into the foundational logic of biosynthetic pathways, characterized by divergent routes from simple building blocks, versus the convergent approaches common in laboratory synthesis. The review highlights cutting-edge methodological integrations, such as hybrid enzymatic-synthetic plans and computational synthesis planning, which overcome limitations inherent to each approach. Through comparative analysis of terpene, polyketide, and pharmaceutical case studies, we evaluate the efficiency, selectivity, and sustainability of these strategies. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this analysis provides a framework for optimizing synthesis routes by leveraging the unique strengths of both biological and chemical catalysis, ultimately pointing toward a more integrated future for molecular construction.

Core Principles: Deconstructing Nature's Divergent Logic versus Chemical Convergent Synthesis

In the realm of total synthesis, a fundamental dichotomy exists between the strategies employed by synthetic chemists and those evolved by nature. While chemists often devise convergent routes with numerous intermediate scaffolds en route to a single product, nature typically operates with divergent pathways that transform a core set of simple building blocks into astonishing structural diversity [1]. This comparative guide examines nature's biosynthetic logic through three foundational precursor classes: acetate (and its activated form, malonyl-CoA), amino acids, and terpene precursors (isopentenyl diphosphate and dimethylallyl diphosphate). Understanding these pathways provides crucial insights for drug development professionals seeking to harness or mimic nature's efficiency in producing complex molecular architectures.

The strategic difference is profound: synthetic chemists frequently create complex routes to navigate around regio- and stereoselectivity challenges, while nature employs enzyme-mediated catalysis to achieve precise control with remarkable efficiency [1]. For instance, a single terpene synthase enzyme can catalyze multiple ring closures, hydride and methyl migrations, and proton abstractions in one active site—transformations that would require numerous steps in a laboratory synthesis [1]. This guide objectively compares the performance of natural biosynthetic strategies against chemical synthetic approaches, providing experimental data and methodologies that highlight both the advantages and limitations of each paradigm.

The Acetate Pathway: Platform for Polyketide Diversity

Natural Biosynthetic Strategy

The acetate pathway, also known as the polyketide pathway, begins with acetyl-CoA and involves the stepwise condensation of two-carbon units, typically derived from malonyl-CoA, to form increasingly longer carbon chains [2]. In nature, this pathway operates at the interface of central metabolism and specialized metabolite synthesis, playing a crucial role in producing both primary metabolites (fatty acids) and secondary metabolites (polyketides) [2] [3]. The fundamental distinction between fatty acid and polyketide biosynthesis lies in the processing of the carbon chain: in fatty acid synthesis, chains are fully reduced after each elongation step, while in polyketide synthesis, the reduction steps may be partially or completely omitted, leading to a diverse array of complex natural products [2].

The pathway's importance extends beyond polyketides, as it also supports flavonoid biosynthesis by providing malonyl-CoA moieties for the C2 elongation reaction catalyzed by chalcone synthase [3]. Research in Arabidopsis thaliana has identified four key enzymes involved in mobilizing carbon resources toward flavonoid biosynthesis: ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (KAT5), enoyl-CoA hydratase (ECH), hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (HCD), and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) [3]. These enzymes form a coordinated system that converts acyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA via acetyl-CoA, demonstrating how primary metabolic resources are directed toward specialized metabolism.

Table 1: Key Enzymes in the Acetate Pathway for Flavonoid Biosynthesis

| Enzyme | Gene ID (Arabidopsis) | Function in Acetate Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| KAT5 | At1g04750 | Catalyzes breakdown of 3-ketoacyl-CoA to produce acetyl-CoA |

| ECH | At1g06550 | Hydrates enoyl-CoA to 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA |

| HCD | At1g65560 | Dehydrogenates 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA to 3-ketoacyl-CoA |

| ACC | At1g36160 | Carboxylates acetyl-CoA to form malonyl-CoA |

Chemical Synthesis Approaches

Unlike nature's building-block approach, chemical synthesis of acetate-derived natural products often employs convergent strategies with numerous intermediate scaffolds. For instance, synthetic routes to staurosporinone demonstrate over ten different synthetic pathways converging to a single product [1]. This approach provides flexibility but typically requires extensive protection/deprotection strategies and generates more waste than enzymatic biosynthesis.

Chemical synthesis excels in creating analog structures not found in nature, which is valuable for drug development when natural compounds have undesirable properties. However, these synthetic approaches often struggle with the stereochemical complexity present in many polyketide natural products, particularly those with multiple chiral centers that are precisely set by enzymatic biosynthesis.

Experimental Protocol: Tracing the Acetate Pathway

Objective: To demonstrate the operation of the acetate pathway in a biological system and identify its products.

Methodology:

- Isotopic Labeling: Introduce (^{13}\text{C})-labeled acetate or malonate to the biological system (cell culture, tissue explants, or enzyme preparation)

- Metabolite Extraction: After incubation, extract metabolites using solvent systems such as methanol/water (1:1, v/v), ethyl acetate, and dichloromethane/methanol (1:1, v/v) at 10:1 (v/w) solvent-to-biomass ratio [4]

- Clean-up Procedure: Purify extracts using SPE Columns C18

- Metabolite Analysis: Analyze using LC-MS/MS to detect (^{13}\text{C}) incorporation patterns

- Data Interpretation: Identify labeled products and determine carbon backbone organization based on labeling patterns

Key Measurements: Incorporation rates of labeled precursors, identification of labeled products, quantification of pathway flux under different conditions.

Terpene Biosynthesis: Nature's Architectural Mastery

Natural Biosynthetic Strategy

Terpenoid biosynthesis represents one of nature's most versatile assembly lines, constructing over 80,000 known structures from two simple C5 building blocks: isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) [4] [5]. These precursors are synthesized through two distinct pathways: the mevalonate (MVA) pathway in the cytoplasm and endoplasmic reticulum, and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway in plastids [6]. The MVA pathway consumes three acetyl-CoA molecules, three ATP equivalents, and two NADPH molecules to yield each IPP molecule, with HMG-CoA reductase catalyzing a key rate-limiting step [6].

The architectural diversity of terpenoids emerges through the action of prenyltransferases, which catalyze "head-to-tail" condensation of DMAPP and IPP to form linear precursors including geranyl diphosphate (GPP, C10), farnesyl diphosphate (FPP, C15), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP, C20) [5] [6]. Terpene synthases then convert these linear precursors to cyclic or acyclic skeletons through carbocation-mediated reactions that may include ring closures, hydride shifts, methyl migrations, and proton abstractions [1] [5]. A remarkable example is tobacco 5-epi-aristolochene synthase (TEAS), which converts farnesyl diphosphate to 5-epi-aristolochene in a single enzymatic step with a (k{cat}/KM) of 0.3 µM(^{-1}) min(^{-1}) [1].

Table 2: Terpene Skeleton Diversity from Common Precursors

| Precursor | Carbon Atoms | Terpene Class | Representative Enzymes | Example Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMAPP | C5 | Hemiterpenes | Isoprene synthase | Isoprene |

| GPP | C10 | Monoterpenes | Limonene synthase | Limonene, pinene |

| FPP | C15 | Sesquiterpenes | 5-Epi-aristolochene synthase | Artemisinin, capsidiol |

| GGPP | C20 | Diterpenes | Taxadiene synthase | Taxadiene, casbene |

| (FPP)₂ | C30 | Triterpenes | Squalene synthase | Squalene, sterols |

| (GGPP)₂ | C40 | Tetraterpenes | Phytoene synthase | Carotenoids |

Chemical Synthesis Approaches

Chemical synthesis of terpenoids faces significant challenges due to their chemical complexity, numerous stereocenters, and limited stability to temperature, light, oxygen, or acidic conditions [5]. Unlike nature's single-enzyme transformations, chemical syntheses often employ semisynthetic strategies from more abundant natural products. For example, (+)-5-epi-aristolochene has been prepared semisynthetically from capsidiol, which is available from pepper fruits in high quantities—notably in reverse order to the biosynthetic pathway where capsidiol is derived from 5-epi-aristolochene [1].

Similarly, the semisynthesis of (-)-premnaspirodiene utilized santonin as starting material in a ring-contracting rearrangement reaction similar to the biosynthetic transformation [1]. These approaches highlight how chemists often deconstruct terpene natural products further along the biosynthetic pathway rather than building them from simple precursors as nature does.

Experimental Protocol: Terpene Synthase Characterization

Objective: To characterize the catalytic activity and product profile of a terpene synthase enzyme.

Methodology:

- Enzyme Preparation: Express terpene synthase gene heterologously in E. coli or yeast and purify using affinity chromatography

- Activity Assay: Incubate purified enzyme with appropriate prenyl diphosphate substrate (GPP, FPP, or GGPP) in assay buffer containing Mg(^{2+}) or Mn(^{2+}) cofactors

- Product Extraction: Extract terpene products with pentane or hexane

- Product Analysis: Analyze products using GC-MS with appropriate chiral columns to resolve stereoisomers

- Kinetic Characterization: Determine (KM) and (k{cat}) values using varying substrate concentrations

Key Measurements: Product identification and quantification, stereochemical configuration of products, catalytic efficiency, side product profile.

Amino Acid-Derived Pathways: Nitrogen-Containing Natural Products

Natural Biosynthetic Strategy

While search results provide limited specific details about amino acid-derived natural products, they confirm that amino acids serve as foundational building blocks for numerous specialized metabolites, particularly through the nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) pathway [1]. Nature employs amino acids as precursors for alkaloids, pigments, antibiotics, and other nitrogen-containing compounds. The shikimate pathway also converts simple carbohydrates to aromatic amino acids, which then serve as precursors for numerous phenolic compounds [3].

The biosynthetic logic parallels terpene and polyketide pathways: nature uses a core set of proteinogenic and non-proteinogenic amino acids that are transformed through enzyme-mediated reactions including decarboxylation, hydroxylation, methylation, and oxidative coupling. These transformations create immense structural diversity while maintaining stereochemical control that is challenging to achieve through laboratory synthesis.

Chemical Synthesis Approaches

Chemical synthesis of amino acid-derived natural products often employs protection strategies for amine and carboxylic acid functionalities, with step-by-step assembly that contrasts with nature's simultaneous activation and coupling in NRPS systems. Solid-phase peptide synthesis has revolutionized the field, but still struggles with complex cyclic structures and non-proteinogenic amino acids that are easily incorporated by enzymatic systems.

Comparative Analysis: Efficiency and Strategic Logic

Building Block Economy

Nature's approach demonstrates superior atom economy by using simple, metabolically accessible building blocks. The terpene pathway is particularly exemplary, creating over 80,000 known structures from just two C5 precursors [5]. Similarly, the acetate pathway constructs both structural lipids and complex polyketides from the same two-carbon unit. This building block economy contrasts with synthetic approaches that often require functionalized starting materials with poor atom economy.

Stereochemical Control

Natural biosynthetic pathways achieve perfect stereochemical control through enzyme-mediated transformations, while chemical synthesis requires carefully designed stereoselective reactions that may require multiple steps and protecting groups. For example, terpene synthases precisely control the stereochemistry of multiple chiral centers in a single enzymatic step [1] [5], whereas chemical synthesis might require separate steps to establish each stereocenter.

Convergent vs. Divergent Strategies

A fundamental strategic difference emerges: chemical synthesis favors convergent approaches where multiple fragments are prepared separately and combined late in the synthesis, while nature employs divergent pathways where a core set of precursors gives rise to multiple products [1]. The convergent approach provides flexibility but generates more synthetic intermediates, while nature's divergent approach maximizes efficiency but with less flexibility in product outcomes.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Biosynthetic vs. Chemical Synthesis

| Parameter | Biosynthetic Approach | Chemical Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Material Complexity | Simple building blocks (acetyl-CoA, IPP, amino acids) | Often complex, pre-functionalized intermediates |

| Stereochemical Control | Perfect control through enzymatic catalysis | Requires designed stereoselective reactions |

| Step Economy | High (e.g., 10+ transformations in one active site) | Lower (multiple separate steps) |

| Structural Diversity Generation | Divergent pathways from core precursors | Convergent routes to specific targets |

| Environmental Impact | Aqueous conditions, biodegradable catalysts | Often organic solvents, metal catalysts |

| Structural Analog Production | Limited by enzyme specificity | Unlimited potential with appropriate route design |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Biosynthetic Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Labeled Precursors ((^{13}\text{C}), (^{14}\text{C}), (^{2}\text{H})) | Metabolic tracing | Pathway elucidation, flux measurements |

| Heterologous Expression Systems (E. coli, yeast) | Enzyme production | Terpene synthase characterization, pathway reconstitution |

| GC-MS with Chiral Columns | Stereochemical analysis | Terpene product profiling, enantiomeric purity |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Metabolite identification and quantification | Polyketide profiling, pathway intermediate detection |

| Gene Silencing Tools (RNAi, CRISPR-Cas9) | Functional gene characterization | Validation of enzyme functions in pathways |

| Isotopic Labeling Analysis (NMR, MS) | Atomic-level tracking | Biosynthetic mechanism elucidation |

The comparative analysis of biosynthetic building blocks reveals nature's elegant efficiency in constructing complex molecular architectures. For drug development professionals, understanding these pathways provides crucial insights for sourcing complex natural products and designing synthetic approaches that balance efficiency with flexibility. While nature's strategies offer unparalleled efficiency for producing specific scaffolds, chemical synthesis provides access to analogs not accessible through biosynthesis.

Future directions point toward hybrid approaches that combine the efficiency of enzymatic transformations with the flexibility of chemical synthesis. Advances in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology now enable reconstruction of biosynthetic pathways in heterologous hosts, potentially providing sustainable production routes for valuable terpene and polyketide pharmaceuticals [5]. Similarly, enzyme engineering creates opportunities to expand nature's catalytic repertoire while maintaining the efficiency of biological catalysis. For drug development professionals, leveraging both biological and chemical synthetic strategies will be essential for addressing the increasing demand for complex natural product-based therapeutics.

In the challenging field of complex molecule construction, convergent synthesis represents a strategically superior approach compared to traditional linear methods. This paradigm involves synthesizing individual pieces of a complex molecule separately before combining them to form the final product, offering significant advantages in overall efficiency and yield [7]. The fundamental strength of this approach lies in its mitigation of the yield reduction inherent in multi-step syntheses—where overall yield drops precipitously with each additional step in a linear sequence [7]. This strategy has profound implications across chemical disciplines, from natural product synthesis and drug discovery to materials science, and presents fascinating parallels and divergences when compared to nature's biosynthetic machinery.

The core mathematical advantage can be illustrated through a simple yield comparison: in a linear synthesis with four steps each proceeding at 50% yield, the overall yield diminishes to a mere 6.25%. In contrast, a convergent approach where two fragments are synthesized in two steps each (both at 50% yield per step) and then coupled (also at 50% yield) maintains an overall yield of 12.5%—a dramatic improvement [7]. This efficiency paradigm makes convergent synthesis particularly valuable for constructing complex, symmetric molecules where multiple identical segments can be synthesized independently and combined [7].

Nature versus The Chemist: Divergent Strategies in Total Synthesis

Nature's Divergent Biosynthetic Logic

Nature employs a fundamentally different strategic approach in building complex molecules. Biological systems often utilize divergent pathways from a core set of simple building blocks to generate astonishing structural diversity [1]. For example, in monoterpene biosynthesis, a single precursor molecule is transformed into a wide array of distinct natural products including (−)-(4S)-limonene, 3-carene, α-thujene, (−)-endo-fenchol, (−)-β-pinene, and 1,8-cineole through organism-specific enzymatic processing [1]. This biosynthetic logic prioritizes the generation of chemical diversity from common precursors using highly specialized enzymes that can dramatically alter molecular architecture through complex transformations.

The enzymatic machinery in nature often accomplishes multiple complex transformations in single reaction vessels. For instance, tobacco 5-epi-aristolochene synthase (TEAS) converts farnesyl diphosphate to (+)-5-epi-aristolochene through a remarkably coordinated process involving two ring closures, a hydride shift, a methyl migration, and a proton abstraction to form a double bond—all within a single enzymatic active site [1]. This biosynthetic efficiency highlights nature's ability to orchestrate numerous chemical events in tandem, a stark contrast to the stepwise laboratory synthesis typically employed by chemists.

The Chemist's Convergent Approach

Synthetic chemists have developed convergent strategies as a response to the practical constraints of laboratory synthesis. Where nature can employ intricate enzymatic systems to perform multiple transformations simultaneously, chemists must often break down complex targets into more manageable fragments that can be synthesized separately and then combined [7]. This approach allows for more efficient optimization of individual synthetic sequences and circumvents the dramatic yield reduction inherent in lengthy linear syntheses.

Recent advances in computer-aided synthesis planning have further optimized this convergent paradigm. Modern computational tools can now identify potential shared synthetic pathways between multiple target molecules, maximizing convergence into shared key intermediates [8]. Analysis of pharmaceutical industry data reveals that over 70% of all reactions in electronic laboratory notebooks are involved in convergent synthesis pathways, covering over 80% of all projects [8], demonstrating the pervasive adoption of this strategy in practical drug discovery.

Table 1: Comparison of Natural Biosynthesis and Laboratory Synthesis Approaches

| Feature | Natural Biosynthesis | Laboratory Convergent Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Strategy | Divergent from common precursors | Convergent from separate fragments |

| Catalysis | Enzyme-mediated | Chemical reagent-mediated |

| Efficiency | High within specialized systems | Improved over linear approaches |

| Scalability | Biological constraints | Engineering considerations |

| Diversity Generation | High from common intermediates | Targeted toward specific molecules |

Quantitative Advantages: Yield and Efficiency Comparisons

The mathematical superiority of convergent synthesis becomes evident when examining yield calculations across multi-step synthetic sequences. The compounding nature of fractional yields in linear syntheses creates an inevitable efficiency bottleneck that convergent strategies directly address.

Table 2: Yield Comparison Between Linear and Convergent Synthesis Approaches

| Synthetic Strategy | Reaction Sequence | Individual Step Yield | Overall Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Synthesis | A → B → C → D | 80% per step | 51.2% |

| Linear Synthesis | A → B → C → D | 50% per step | 12.5% |

| Convergent Synthesis | A → B (2 steps); C → D (2 steps); B + D → E | 80% per step | 64.0% |

| Convergent Synthesis | A → B (2 steps); C → D (2 steps); B + D → E | 50% per step | 25.0% |

The tabulated data clearly demonstrates that the yield advantage of convergent synthesis becomes increasingly pronounced as both the number of steps and the individual step yields decrease. This mathematical reality makes convergent approaches particularly valuable for constructing complex molecular architectures requiring numerous synthetic steps, where even optimized reactions may proceed in modest yields due to the structural complexity involved.

Beyond simple yield calculations, convergent synthesis offers practical advantages in intermediate characterization and purification. Complex fragments can be fully characterized and purified before the final coupling steps, ensuring structural integrity and reducing the accumulation of impurities that can occur throughout lengthy linear sequences. This modularity also enables parallelization of synthetic efforts, where different research teams or facilities can focus on optimizing separate fragments before their ultimate combination [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Convergent Synthesis in Dendrimer Construction

Dendrimers represent a classic application of convergent synthesis principles, where highly branched, monodisperse macromolecules are constructed through controlled iterative processes. The convergent approach to dendrimer synthesis begins from the periphery and progresses inward toward a reactive core, contrasting with the divergent approach that starts from a central core and extends outward [10].

The experimental protocol for convergent dendrimer synthesis typically involves:

- Separate synthesis of dendritic wedges or fragments with precise control over generation growth

- Activation of the focal point of these wedges for subsequent coupling reactions

- Final coupling of multiple dendritic wedges to a polyfunctional core molecule

- Purification and characterization at each stage to ensure structural fidelity

This approach offers significant advantages for dendrimer synthesis, including reduced structural defects, easier purification of intermediate fragments, and better control over surface functionality. Poly(ether-imide) dendrimers are typically synthesized using this convergent methodology, while other classes like PAMAM and PPI dendrimers are more commonly prepared through divergent approaches [10].

Convergent Strategies in Natural Product Synthesis

The total synthesis of complex natural products represents one of the most demanding applications of convergent synthesis. A representative example can be found in the synthesis of biyouyanagin A, where a photochemical [2+2] cycloaddition serves as the final convergent step to unite two complex fragments [7]. This strategic bond disconnection allows for the independent construction of the two molecular hemispheres before their final union.

Experimental protocols for such convergent natural product syntheses typically involve:

- Retrosynthetic analysis to identify optimal fragment disconnect sites

- Independent optimization of synthetic sequences for each fragment

- Development of coupling conditions compatible with the functional groups present in both fragments

- Final elaboration to the complete natural product structure after fragment union

This approach has been successfully applied to the synthesis of numerous complex natural products, including staurosporinone, for which over ten different synthetic routes have been developed that converge to the single final product [1].

Convergent Synthesis of Functional Materials

The convergent paradigm extends beyond natural product synthesis to functional material development. A representative example includes the creation of conductive liquid metal hydrogels with self-healing properties through convergent synthesis of complex polymer networks [9]. The experimental workflow involves:

Individual synthesis of four specialized precursors in one to two reaction steps each:

- Tannic acid-coated liquid metal nanodroplets (PLM-TA)

- Catechol-functionalized chitosan (PCHI-C)

- Cholesteryl and aldehyde-modified dextran (PDex-ALD-CH)

- PEDOT:Hep (Pcp) conductive polymer

Comprehensive characterization of each precursor before assembly

Convergent assembly through mixing of all components to form dynamic electroconductive biopolymer/liquid metal hybrid hydrogels (DECPLMH)

This convergent strategy allows for the incorporation of materials with vastly different natures into a single functional matrix, combining polysaccharides, conductive biopolymers, and liquid metal nanodroplets [9]. The resulting materials exhibit enhanced adhesiveness, electroconductivity, injectability, and compatibility with 3D printing and in vivo applications.

Diagram 1: Convergent Synthesis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of convergent synthesis strategies requires specialized reagents and building blocks designed for efficient fragment coupling and compatibility with diverse functional groups.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Convergent Synthesis Methodologies

| Reagent/Building Block | Function in Convergent Synthesis | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Tannic Acid-Coated Liquid Metal Nanodroplets | Functional filler providing conductivity and self-healing properties | Conductive hydrogel formation [9] |

| Catechol-Functionalized Chitosan | Adhesive polymer backbone with catechol groups for cross-linking | Bioadhesive materials [9] |

| Aldehyde-Modified Dextran | Polysaccharide precursor providing aldehyde groups for Schiff base formation | Reversible polymer networks [9] |

| PEDOT:Hep Conductive Polymer | Electroconductive component for signal transmission | Bioelectronic interfaces [9] |

| Dendritic Wedges with Focal Point Reactivity | Pre-assembled branched fragments for dendrimer synthesis | Dendrimer construction [10] |

| Photocycloaddition Capable Partners | Fragments designed for [2+2] or higher-order cycloadditions | Natural product synthesis [7] |

Computational Approaches to Convergent Route Planning

Modern computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) has revolutionized the identification and optimization of convergent synthetic routes. Advanced algorithms can now navigate chemical space to identify optimal disconnect points and potential shared intermediates across multiple target molecules [8]. These systems employ graph-based processing pipelines to extract convergent routes from reaction databases, identifying complex synthetic pathways where multiple target molecules share common intermediates.

The computational workflow for convergent synthesis planning typically involves:

- Reaction network construction from known synthetic transformations

- Identification of shared intermediates across multiple target molecules

- Retrosynthetic analysis using state-of-the-art machine learning models

- Route optimization based on yield, step count, and convergence metrics

Analysis of pharmaceutical industry data reveals that computational approaches can identify convergent routes for over 80% of test cases, with individual compound solvability exceeding 90% [8]. This computational capability enables the simultaneous planning of synthetic routes for hundreds of molecules, identifying shared convergent pathways that would be difficult to recognize through manual analysis alone.

Diagram 2: Computational Route Planning

The convergent synthesis paradigm represents a fundamental strategic advantage in complex molecule construction, enabling improved efficiency, yield, and modularity compared to traditional linear approaches. While nature employs divergent biosynthetic strategies to generate chemical diversity from common precursors, synthetic chemists have developed convergent methodologies to overcome the practical limitations of laboratory synthesis. The integration of computational planning tools with experimental execution has further enhanced our ability to identify and implement optimal convergent routes to complex targets.

As synthetic challenges continue to grow in complexity, from functional materials to pharmaceutical targets, the principles of convergent synthesis will remain essential for achieving practical synthetic outcomes. The ongoing development of new coupling methodologies, protective group strategies, and computational planning algorithms will further expand the scope and efficiency of this powerful synthetic paradigm, enabling the construction of increasingly complex molecular architectures through the strategic assembly of simpler fragments.

Terpenoids constitute the largest family of natural products, with over 95,000 known compounds exhibiting impressive biological activities, including anticancer, antimalarial, and antifungal properties. [11] The biosynthesis of these complex molecules begins with simple C5 isoprenoid building blocks—isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP)—which are assembled into linear prenyl diphosphates such as farnesyl diphosphate (FPP, C15). [11] At the heart of terpenoid structural diversity are terpene cyclases (TCs), enzymes that catalyze the conversion of acyclic precursors into an astonishing array of cyclic skeletons. [11] [12] This case study examines how nature employs a divergent synthetic strategy, using a common FPP intermediate to generate structurally distinct terpene skeletons through the action of different terpene cyclases, and contrasts this approach with the convergent strategies typically employed by synthetic chemists.

In nature, a single precursor molecule can be converted to a huge variety of known terpenes in different organisms. [1] This divergent biosynthetic strategy stands in stark contrast to traditional organic synthesis, where routes to natural products are often characterized by convergent approaches: numerous intermediate scaffolds can be en route to a single product. [1] The comparison between these strategies reveals fundamental differences in synthetic logic, with nature optimizing for diversification from common intermediates, while chemists often focus on converging multiple pathways toward a single target.

Terpene Cyclase Classification and Reaction Mechanisms

Terpene cyclases are categorized into two classes based on their reaction mechanisms and structural features: [11] [13]

Table: Classification of Terpene Cyclases

| Feature | Class I Terpene Cyclases | Class II Terpene Cyclases |

|---|---|---|

| Initiation Mechanism | Metal-dependent ionization of diphosphate ester | Protonation of C=C double bond or epoxide |

| Characteristic Motifs | DDXXD and NSE/DTE motifs | DXDD motif |

| Metal Cofactors | Mg²⁺ or Mn²⁺ (trinuclear cluster) | Not typically metal-dependent for initiation |

| Structural Domains | Catalytic α-domain (class I activity) | Functional β and γ domains (class II activity) |

| Primary Function | Chain elongation (prenyltransferases) and cyclization | Cyclization exclusively |

Class I TCs initiate cyclization by metal-dependent ionization of the diphosphate ester, generating an allylic carbocation. [13] This mechanism is shared by both cyclases and the prenyltransferases that create the linear precursors. In contrast, canonical class II TCs initiate cyclization by protonating a double bond or epoxide of the substrate, leaving any present diphosphate group intact. [11] Class II TCs can also act on terpene moieties previously appended onto non-terpenoids, known as meroterpenoid cyclases (MTCs). [11]

The ensuing cyclization pathways involve complex sequences of carbocation rearrangements—including hydride shifts, methyl shifts, and ring expansions—before termination through deprotonation or nucleophile capture. [11] [12] The terpene cyclases guide these reactive intermediates through specific three-dimensional trajectories within protective active site pockets, enabling the formation of distinct stereochemical outcomes from identical substrates. [12]

Figure 1. Divergent cyclization pathways from FPP. The common FPP intermediate can be converted to various sesquiterpenes through different carbocationic routes.

Experimental Analysis of Terpene Cyclization Pathways

Product Analysis via Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

GC-MS analysis serves as the primary method for identifying and quantifying terpene cyclase products. [14] [13] The experimental protocol typically involves:

- Enzyme incubation: Purified terpene cyclase is incubated with substrate (FPP or analogs) in appropriate buffer with essential cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺ for class I TCs). [14]

- Product extraction: Hydrophobic terpene products are extracted using organic solvents such as tert-butyl methyl ether (TBME). [15]

- Chromatographic separation: Compounds are separated using a non-polar GC column (e.g., DB-5) with temperature gradient programming. [15] [14]

- Mass spectrometric detection: Electron impact ionization generates characteristic fragmentation patterns for compound identification. [14] [13]

This methodology enables researchers to determine the product profile of a terpene cyclase, including major and minor products, which reflects the enzyme's catalytic precision and potential reaction mechanisms.

Steady-State Kinetic Analysis

The catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) of terpene cyclases is determined through steady-state kinetic assays. [13] For terpene cyclases that generate multiple products, the relative ratios of these products should be comparable to the ratio of kcat/KM values when two cyclases compete for the same substrate. [13] A coupled enzyme fluorescence assay has been developed using the EnzChek Pyrophosphate Assay Kit, which couples pyrophosphate release to a fluorescent signal, enabling continuous monitoring of terpene cyclase activity. [13]

Isotopic Labeling Studies

Mechanistic insights into terpene cyclization pathways are obtained through isotopic labeling experiments. [14] For example, incubation of δ-cadinene synthase with (1RS)-1-²H-FPP resulted in exclusive formation of [5-²H] and [11-²H] δ-cadinene, revealing specific hydride shifts during the cyclization cascade. [14] Similarly, studies with (3RS)-[4,4,13,13,13-²H₅]-nerolidyl diphosphate demonstrated that the (3R)-enantiomer is the active cyclization intermediate. [14]

Table: Product Distribution from δ-Cadinene Synthase with Different Substrates

| Substrate | Products | Percentage | Labeling Pattern in Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1RS)-1-²H-FPP | δ-Cadinene | >98% | [5-²H] and [11-²H] δ-Cadinene |

| (3RS)-[4,4,13,13,13-²H₅]-NDP | δ-Cadinene | 62.1% | [8,8,15,15,15-²H₅] δ-Cadinene |

| α-Bisabolol | 15.8% | [6,6,15,15,15-²H₅] α-Bisabolol | |

| β-Bisabolene | 8.1% | [6,6,15,15,15-²H₅] β-Bisabolene | |

| (E)-β-Farnesene | 9.8% | [4,4,13,13-²H₄] (E)-β-Farnesene |

Case Studies: Divergent Cyclization from FPP

TEAS and HPS: Minimal Structural Changes, Dramatic Functional Consequences

The comparison between tobacco 5-epi-aristolochene synthase (TEAS) and henbane premnaspirodiene synthase (HPS) provides a striking example of divergent evolution in terpene cyclases. These enzymes share 75% amino acid identity yet produce dramatically different terpene skeletons from the common FPP substrate. [1]

TEAS converts FPP to 5-epi-aristolochene through a mechanism involving two ring closures, a hydride and a methyl migration, and a proton abstraction. [1] In contrast, HPS catalyzes two ring closures, a methylene shift, and abstraction of a distinct proton to form premnaspirodiene, a spirovetivane with three stereocenters. [1] The divergence occurs after formation of a common bicyclic intermediate, where TEAS initiates a 1,2-methyl shift while HPS triggers a 1,2-shift of the cycloalkyl substituent. [1]

Structural analysis revealed that only nine amino acid substitutions are responsible for this functional divergence. [1] Systematic evaluation of 418 mutant combinations demonstrated that single amino acid mutations do not necessarily cause predictable changes in enzyme activity, revealing a complex catalytic landscape for terpene cyclase function. [1]

δ-Cadinene Synthase: Multiple Products from Alternative Substrates

δ-Cadinene synthase from cotton provides another compelling case of divergent cyclization. This enzyme cyclizes (E,E)-FDP to a single product, δ-cadinene, with >98% fidelity. [14] However, when provided with the potential intermediate (3RS)-nerolidyl diphosphate, the enzyme produces multiple sesquiterpenes including δ-cadinene (62.1%), α-bisabolol (15.8%), β-bisabolene (8.1%), and (E)-β-farnesene (9.8%). [14]

Competitive studies demonstrated that the (3R)-nerolidyl diphosphate enantiomer is the active intermediate that cyclizes to δ-cadinene. [14] The kcat/KM values show that the synthase uses (E,E)-FDP as effectively as (3R)-nerolidyl diphosphate in the formation of δ-cadinene, suggesting a direct cyclization mechanism without a free nerolidyl intermediate. [14]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table: Key Research Reagents and Methods for Terpene Cyclase Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Farnesyl Diphosphate (FPP) | Primary substrate for sesquiterpene cyclases | Commercially available or synthesized enzymatically |

| Isotopically Labeled FPP Analogs | Mechanistic studies of cyclization pathways | e.g., (1RS)-1-²H-FPP for tracking hydride shifts |

| Mg²⁺ or Mn²⁺ ions | Cofactors for class I terpene cyclases | Typically used at 10 mM concentration in assays |

| EnzChek Pyrophosphate Assay Kit | Coupled enzyme assay for continuous monitoring | Measures pyrophosphate release fluorometrically |

| GC-MS System | Product identification and quantification | DB-5 capillary column standard for terpene separation |

| His-tagged Enzyme Constructs | Protein purification for biochemical studies | pET28a(+) vector commonly used for bacterial expression |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Synthesis

The divergent strategies employed by nature in terpene biosynthesis offer valuable lessons for drug discovery and development. Understanding how minimal structural changes in enzyme active sites can redirect synthetic pathways provides inspiration for biomimetic catalyst design. [1] The terpene cyclase family demonstrates how nature generates structural diversity from minimal building blocks, a principle that can be applied to create diverse compound libraries for pharmaceutical screening.

Furthermore, the study of terpene cyclases has significant implications for enzyme engineering efforts. The modular domain architecture of terpene cyclases, along with the identification of key active site residues that control product specificity, enables the rational design of novel catalysts for the production of desired terpenoid compounds. [11] [1] As structural and mechanistic understanding of terpene cyclases deepens, the potential for engineering these enzymes to create non-natural terpenoid skeletons with tailored pharmaceutical properties continues to grow.

Figure 2. Comparison of natural biosynthetic and chemical synthetic strategies. Nature employs divergent approaches from common intermediates, while chemists typically use convergent routes to single targets.

This case study illustrates the fundamental synthetic logic underlying nature's approach to terpenoid diversity: divergent pathways from common intermediates controlled by specialized terpene cyclases. Through minimal alterations in active site architecture, nature redirects the reactive carbocationic intermediates derived from FPP down distinct cyclization pathways to generate structural diversity. This stands in contrast to the convergent strategies typically employed in laboratory synthesis, where multiple pathways are developed to reach a single target compound.

The study of terpene cyclases not only reveals nature's synthetic strategies but also provides powerful tools for biocatalytic applications. As our understanding of terpene cyclase structures and mechanisms deepens, the potential to harness these enzymes for sustainable production of valuable terpenoid natural products and pharmaceutical precursors continues to expand, bridging the gap between nature's synthetic prowess and human chemical ingenuity.

In the quest to synthesize complex natural products, chemists and nature employ fundamentally different, yet often complementary, strategies. Nature's approach, honed over billions of years of evolution, relies on template-driven enzymatic assembly—a highly efficient, pre-programmed process utilizing mega-enzymes like polyketide synthases (PKSs) and non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) [16]. These enzymatic assembly lines select and combine building blocks through a series of condensation reactions, often followed by tailored modifications, to produce structurally complex molecules with exquisite stereocontrol. In stark contrast, the synthetic chemist's toolkit is dominated by a logic of stepwise functional group manipulation and strategic bond disconnections, where reactions like electrophilic attacks and rearrangements are deployed to build molecular complexity iteratively [17] [18].

This article objectively compares these paradigms, focusing on the roles of electrophilic substitution and sigmatropic rearrangements as core mechanisms for C-C and C-X bond formation. We present experimental data and protocols to evaluate the efficiency, stereoselectivity, and applicability of these methods in constructing architecturally complex natural products, providing a comparative guide for researchers in drug development and synthetic science.

Core Mechanism 1: Electrophilic Attacks

Electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS) is a cornerstone reaction for functionalizing aromatic systems, a common scaffold in many natural products and pharmaceuticals. The mechanism is a two-step process involving a rate-determining electrophilic attack followed by deprotonation to restore aromaticity [19].

Mechanism and Regioselectivity

The initial attack of an electrophile (E+) on the aromatic ring generates a resonance-stabilized carbocation intermediate (arenium ion). The subsequent deprotonation reforms the aromatic system, resulting in overall substitution [19]. A critical aspect for synthesis is regiocontrol. Existing substituents on the ring powerfully direct the incoming electrophile to specific positions:

- Ortho/Para Directors: Electron-donating groups (e.g., -OH, -NH₂, -alkyl) activate the ring and direct substitution to the ortho and para positions [19].

- Meta Directors: Electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., -NO₂, -COOH, -C≡N) deactivate the ring and direct substitution primarily to the meta position [19].

This directing effect is powerfully illustrated by the nitration of toluene (an ortho/para director) versus nitrobenzene (a meta director), which yield vastly different product distributions [19].

Experimental Protocol: Electrophilic Bromination using N-Bromosuccinimide (NBS)

Title: Regioselective Bromination of Activated Arenes using NBS and a Lewis Acid Catalyst [20]

Principle: N-Halosuccinimides (NXS), such as NBS, are excellent halogenating reagents due to their stability, low cost, and ease of handling. For moderately reactive arenes, a Lewis acid catalyst (e.g., FeCl₃) activates NBS by coordinating to the carbonyl oxygen, enhancing its electrophilicity [20].

Materials:

- Substrate: Activated arene (e.g., anisole, toluene)

- Reagent: N-Bromosuccinimide (NBS)

- Catalyst: Anhydrous Iron(III) Chloride (FeCl₃)

- Solvent: Anhydrous Acetonitrile (MeCN)

- Work-up: Aqueous sodium thiosulfate solution, organic solvent for extraction

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Charge an oven-dried round-bottom flask with a magnetic stir bar. Under a nitrogen atmosphere, add the arene substrate (1.0 mmol) and anhydrous MeCN (5 mL).

- Catalyst Addition: Add anhydrous FeCl₃ (0.1 mmol, 10 mol%) to the stirring solution.

- Reagent Addition: Add NBS (1.1 mmol) portion-wise to the reaction mixture at room temperature.

- Monitoring: Stir the reaction at room temperature and monitor by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) until the starting material is consumed.

- Quenching: Quench the reaction by adding a saturated aqueous sodium thiosulfate solution (5 mL).

- Extraction: Transfer the mixture to a separatory funnel and extract with ethyl acetate (3 x 10 mL).

- Isolation: Combine the organic layers, dry over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Purify the crude product by flash column chromatography on silica gel.

Performance Comparison of Electrophilic Halogenation Methods

The following table compares different electrophilic halogenation methods for aromatic compounds, highlighting the reagents and conditions used for substrates of varying reactivity.

| Method / Reagent System | Target Reactivity Class | Key Feature | Reported Yield Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| NBS/FeCl₃ in MeCN [20] | Moderately Reactive Arenes | Broad substrate scope, good regioselectivity | Good Yields |

| NBS in BF₃–H₂O [20] | Electron-Deficient Arenes | Effective for deactivated rings | Good Yields |

| NBS with ZrCl₄ Catalyst [20] | Activated Arenes | Selective monohalogenation | Good Yields |

| NBS in Hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) [20] | Activated Arenes & Heterocycles | No added catalyst, high regioselectivity | Good Yields |

| NBS with (PhSO₂)₂NF [20] | Highly Reactive Arenes (Phenols/Anilines) | Fast and clean reaction at low temp | Excellent Yields |

Core Mechanism 2: Rearrangement Reactions

Rearrangement reactions offer unparalleled efficiency in natural product synthesis by enabling rapid skeletal reorganization and the stereoselective construction of congested carbon frameworks in a single step [17] [18].

The Power of [3,3]-Sigmatropic Rearrangements

Among pericyclic reactions, [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangements—such as the Cope, oxy-Cope, and Claisen rearrangements—are exceptionally valuable. They function as a "well-defined method for the stereoselective construction of carbon–carbon or carbon–heteroatom bonds" while enabling a significant build-up of molecular complexity [17]. Their utility is demonstrated in complex settings:

- In the synthesis of (-)-colombiasin A, a C–H activation step is followed by a facile [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement at ambient temperature, efficiently setting a key quaternary stereocenter and establishing the core polycyclic structure [17].

- Tandem sequences incorporating these rearrangements are particularly powerful. For instance, a single operation featuring a tandem oxy-Cope–Claisen–ene reaction was used as the keystone for synthesizing the diterpene wiedermannic acid, constructing multiple rings and stereocenters with high fidelity [17].

- The aza-Cope–Mannich rearrangement strategy has been successfully deployed to assemble the intricate 1-azatricyclic core of alkaloids like FR901483 and didehydrostemofoline [17].

Experimental Protocol: A Tandem Oxy-Cope–Claisen–Ene Reaction

Title: One-Pot Tandem Rearrangement for the Construction of Polycyclic Terpene Cores [17]

Principle: This cascade process begins with an oxy-Cope rearrangement of a 1,5-dien-3-ol system, which is accelerated by the presence of an alkoxide. The resulting 10-membered ring enol ether then undergoes a Claisen rearrangement, followed by a transannular ene reaction to deliver a complex polycyclic product in one pot.

Materials:

- Substrate: 1,5-Dien-3-ol (e.g., compound 9 from isopulegone)

- Base: Potassium hydride (KH)

- Solvent: Anhydrous Tetrahydrofuran (THF)

- Work-up: Aqueous ammonium chloride solution, organic solvent for extraction

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Synthesize the 1,5-dien-3-ol substrate according to literature procedures.

- Deprotonation: In an oven-dried flask under inert atmosphere, dissolve the substrate (1.0 mmol) in anhydrous THF (0.1 M concentration). Cool to 0°C and add KH (1.2 mmol) portion-wise. Stir for 30 minutes at 0°C.

- Heating: Seal the reaction vessel and heat under microwave irradiation at 210°C for 1 hour. Note: Conventional oil bath heating at reflux temperature for an extended period may also be used, but microwave irradiation significantly reduces reaction time.

- Monitoring: Monitor the reaction by TLC or GC-MS for consumption of the starting material.

- Quenching: Carefully quench the reaction with a saturated aqueous NH₄Cl solution (10 mL).

- Extraction and Isolation: Extract the aqueous layer with diethyl ether (3 x 15 mL). Combine the organic extracts, dry over Na₂SO₄, filter, and concentrate.

- Purification: Purify the crude product by flash chromatography on silica gel to yield the polycyclic product.

Comparative Analysis: Nature's Biosynthesis vs. Laboratory Synthesis

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in strategy between natural biosynthesis and laboratory synthesis for complex molecule assembly.

Comparative Efficiency Metrics

The table below provides a performance comparison of key strategies based on data from published syntheses.

| Strategy / Reaction | Representative Natural Product | Key Metric (Yield) | Step Count (Key Step to Core) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Assembly [16] | Various Polyketides (e.g., Erythromycin) | High In Vivo Efficiency | N/A (Template-Directed) |

| Tandem Oxy-Cope/Claisen/Ene [17] | Wiedermannic Acid Analog | 90% Yield (Key Step) | 1 (Key Tandem Sequence) |

| C–H Activation / Cope Rearrangement [17] | (-)-Elisapterosin B | >95% ee | 7 steps (from common intermediate) |

| Aza-Cope–Mannich Cascade [17] | (±)-Didehydrostemofoline | 94% Yield (Key Step) | Early-stage cyclization |

| Anodic Oxidation Cyclization [21] | (+)-Nemorensic Acid | 71% Yield | Key step in 7-step sequence |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of these synthetic strategies requires a carefully selected set of reagents and catalysts.

Research Reagent Solutions for Electrophilic and Rearrangement Chemistry

| Reagent / Material | Function / Utility | Key Feature / Application |

|---|---|---|

| N-Halosuccinimides (NXS) [20] | Electrophilic halogen source for aromatic substitution. | Stable, low-cost, easy to handle; used for bromination (NBS), chlorination (NCS), iodination (NIS). |

| Lewis Acids (e.g., FeCl₃, ZrCl₄) [20] | Activates NXS by coordinating to carbonyl oxygen. | Enhances electrophilicity; enables halogenation of moderately reactive arenes. |

| Hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) [20] | Solvent for electrophilic halogenation. | Promotes reaction without added catalyst; offers high regioselectivity. |

| 1,5-Dien-3-ol Systems [17] | Substrate for oxy-Cope rearrangement. | The alkoxide form undergoes rapid [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement at elevated temperatures. |

| Ketene Dithioacetals [21] | Substrate for anodic oxidation cyclization. | Low oxidation potential enables radical cation formation and intramolecular C-O bond formation. |

| Silyl Enol Ethers [21] | Substrate for anodic oxidation cyclization. | Generates radical cation for umpolung reactivity, trapped by pendant nucleophiles. |

The strategic comparison between Nature's biosynthetic assembly lines and the chemist's reliance on electrophilic attacks and rearrangement reactions reveals a powerful dichotomy. Nature's approach achieves unparalleled efficiency through enzymatic processivity and three-dimensional control within mega-synthases, but can be inflexible and difficult to reprogram for novel analogs [16]. In contrast, laboratory synthesis, while often step-intensive, offers ultimate flexibility through the rational deployment of discrete, high-impact reactions like regioselective electrophilic substitutions and complexity-generating sigmatropic rearrangements [19] [17] [18].

The future of natural product synthesis and diversification lies not in choosing one paradigm over the other, but in their strategic integration. Emerging techniques in combinatorial biosynthesis and enzyme engineering seek to introduce the chemist's logic of modularity and promiscuity into natural systems [22] [16]. Simultaneously, synthetic electrochemistry is providing new, sustainable ways to perform key oxidative and reductive transformations, expanding the chemist's toolkit for complex molecule assembly [21]. This synergistic approach, leveraging the strengths of both biological and chemical logic, promises to accelerate the discovery and development of novel therapeutic agents inspired by nature's architectural genius.

Integrated Toolkits: Combining Enzymatic, Synthetic, and Computational Strategies

The field of total synthesis has long been characterized by two distinct philosophical approaches: the strategies employed by nature and those designed by chemists. Biosynthetic pathways in living organisms are inherently divergent, often starting from a core set of simple building blocks that are transformed into an astonishing diversity of natural products through enzyme-catalyzed reactions [1]. In contrast, traditional organic synthesis, particularly for complex natural products, typically employs convergent approaches where numerous intermediate scaffolds are strategically assembled into a single target molecule [1]. Hybrid synthesis planning represents a paradigm shift that seeks to leverage the unique strengths of both worlds, creating synergistic routes that combine the selectivity and sustainability of enzymatic transformations with the broad scope and robustness of synthetic organic chemistry.

The fundamental challenge in hybrid synthesis planning lies in the historical separation of the computational tools designed for these two domains. Conventional Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) tools have been specialized for either fully synthetic [23] or fully enzymatic [23] synthesis planning, creating an artificial divide that limits the exploration of hybrid pathways. This review comprehensively compares emerging algorithms specifically designed to bridge this gap, evaluating their performance, methodologies, and practical applicability for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement the most efficient synthesis strategies.

Comparative Analysis of Hybrid Synthesis Planning Algorithms

Algorithm Architectures and Core Methodologies

Table 1: Core Architectural Features of Hybrid Synthesis Planning Algorithms

| Algorithm/Platform | Developer/Institution | Reaction Proposal Method | Enzymatic Templates | Synthetic Templates | Search Strategy | Ranking Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid Retrosynthetic Search | Various researchers [23] | Template-based (Dual NN) | 7,984 (BKMS database) | 163,723 (Reaxys) | Balanced exploration | Neural network scoring |

| ACERetro (SPScore-guided) | Scientific research team [24] | Template-based | Not specified | Not specified | Asynchronous search | Synthetic Potential Score (SPScore) |

| DORAnet | Northwestern University [25] | Template-based | 3,606 (MetaCyc) | 390 (Expert-curated) | Customizable network expansion | Customizable criteria |

The architectural foundation of hybrid planning algorithms primarily utilizes template-based approaches, where predefined reaction rules—derived from extensive reaction databases—are applied to identify potential retrosynthetic steps [25]. These algorithms differ fundamentally in how they integrate and balance the exploration of enzymatic versus synthetic transformations.

The Hybrid Retrosynthetic Search Algorithm employs two separate neural network models—one trained on 7,984 enzymatic transformations from the BKMS database and another on 163,723 synthetic transformations from Reaxys—that work in concert to prioritize retrosynthetic moves [23]. This dual-model architecture explicitly addresses the statistical dominance of synthetic reactions in combined databases by implementing a balancing mechanism that ensures enzymatic transformations receive adequate consideration during pathway exploration [23].

ACERetro introduces a unified scoring metric called the Synthetic Potential Score (SPScore), developed by training a multilayer perceptron on existing reaction databases to evaluate the potential of both enzymatic and organic reactions for synthesizing a target molecule [24]. This approach enables an asynchronous search algorithm that has demonstrated capability to find hybrid synthesis routes for 46% more molecules compared to previous state-of-the-art tools [24].

DORAnet (Designing Optimal Reaction Avenues Network Enumeration Tool) provides an open-source framework with extensive template libraries—3,606 enzymatic rules derived from MetaCyc and 390 expert-curated chemical/chemocatalytic rules [25]. Its modular, object-oriented architecture prioritizes customizability and scalability, offering researchers full control over reaction rules, expansion strategies, and filtering criteria [25].

Performance Benchmarking and Validation

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Hybrid Synthesis Planning Algorithms

| Performance Metric | Hybrid Retrosynthetic Search | ACERetro | DORAnet |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Discovery Rate | Finds routes when single-mode searches fail [23] | 46% more molecules than previous tools [24] | Frequently ranks known pathways in top 3 [25] |

| Route Efficiency | Designs shorter pathways for some targets [23] | Demonstrated efficient hybrid routes for FDA-approved drugs [24] | Identifies highly-ranked alternative pathways [25] |

| Case Study Validation | (-)-Δ9-THC (dronabinol) and R,R-formoterol [23] | 4 FDA-approved drugs [24] | 51 high-volume industrial chemicals [25] |

| Template Coverage | Adds 4,169 unique enzymatic templates [23] | Not specified | Covers C, H, O, N, S transformations [25] |

Performance validation across these platforms demonstrates their complementary strengths. The Hybrid Retrosynthetic Search algorithm has been shown to discover viable routes to molecules for which purely synthetic or enzymatic searches find none, while also designing shorter pathways for certain targets [23]. Application to pharmaceutical compounds like (-)-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and R,R-formoterol illustrates how hybrid planning can replace metal catalysis, high step counts, or costly enantiomeric resolution with more efficient hybrid proposals [23].

ACERetro's performance advantage is particularly notable in its benchmarked ability to find routes for nearly half again as many molecules as previous tools [24]. This significant improvement in pathway discovery rate highlights the effectiveness of its SPScore-guided asynchronous search strategy.

DORAnet demonstrates strong practical relevance through its validation against 51 high-volume industrial chemicals, where it frequently ranked known commercial pathways among the top three results while simultaneously uncovering numerous novel hybrid alternatives [25]. This performance indicates robust ranking accuracy alongside innovative pathway discovery.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Curation and Template Extraction

The foundation of reliable hybrid synthesis planning rests on comprehensive data curation. For enzymatic reaction data, the BKMS database provides approximately 37,000 enzyme-catalyzed reactions aggregated from BRENDA, KEGG, Metacyc, and SABIO-RK [23]. Processing involves removing biological cofactors, converting reactions to standardized SMILES strings, and performing atom-atom mapping to track correspondence between reactant and product atoms [23]. Through this process, 15,309 unique, single-product, atom-mapped reaction SMILES strings were generated, from which 7,984 unique reaction templates were extracted using RDChiral [23].

For synthetic chemistry, the Reaxys database provides the foundation for template extraction, containing over 10 million reactions with enzymatic transformations representing only a small fraction (~5×10⁴ versus >10⁷ total reactions) [23]. This disparity in data representation necessitates algorithmic balancing mechanisms to prevent synthetic transformations from dominating the search process.

Network Expansion and Pathway Search

The core algorithmic workflow for hybrid synthesis planning follows a retrosynthetic approach, beginning with the target molecule and recursively applying reaction templates to identify plausible precursors until pathways to commercially available starting materials are found. The search space grows exponentially with depth, making brute-force enumeration computationally intractable and necessitating sophisticated prioritization strategies [23].

The Hybrid Retrosynthetic Search algorithm employs a balanced exploration strategy that uses separate neural network models for enzymatic and synthetic transformations to score potential retrosynthetic moves, ensuring both reaction types receive consideration at each decision point [23].

ACERetro implements an asynchronous search strategy guided by the Synthetic Potential Score, which evaluates the likelihood of both enzymatic and synthetic transformations based on molecular structure [24]. This unified scoring enables more efficient navigation of the hybrid chemical space.

DORAnet provides customizable expansion strategies with advanced filtering capabilities, allowing researchers to tailor the search process based on available computational resources and specific research objectives [25]. Its open-source architecture supports implementation of both breadth-first and depth-first search variants with customizable depth limits.

Pathway Ranking and Evaluation Metrics

Pathway ranking constitutes a critical component of hybrid synthesis planning, with different algorithms employing distinct evaluation frameworks:

- The Synthetic Potential Score (SPScore) in ACERetro is generated by a multilayer perceptron trained on reaction databases to prioritize promising reaction types [24]

- Step count and convergence serve as primary efficiency metrics across platforms

- Atom economy and environmental sustainability considerations can be incorporated through customizable ranking criteria [25]

- Precedent support for individual transformations provides practical confidence in proposed steps [23]

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Hybrid Synthesis Planning

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function/Role | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Databases | BKMS [23], MetaCyc [25], Reaxys [23] | Source of enzymatic and synthetic transformations | BKMS: ~37,000 enzymatic reactions; Reaxys: >10⁷ total reactions |

| Template Libraries | Expert-curated chemical rules [25], Enzymatic rules from MetaCyc [25] | Encode transformation patterns as SMARTS | 390 chemical + 3,606 enzymatic rules in DORAnet |

| Software Tools | RDChiral [23], RDKit [25] | Molecule manipulation and reaction application | SMILES processing, substructure matching, stereochemistry handling |

| Platform Environments | DORAnet [25], ASKCOS [23], RetroBioCat [23] | Integrated synthesis planning | Open-source frameworks with customizable expansion strategies |

Philosophical Context: Nature's Logic Versus Chemical Design

The development of hybrid synthesis planning algorithms represents more than a technical advancement—it embodies a philosophical reconciliation between nature's biosynthetic strategies and human chemical design principles. Natural biosynthetic pathways exhibit characteristics fundamentally different from engineered systems: massive overlapping of functions, standard-free complexity, and context-dependent performance of biological components [26]. Where engineered systems achieve robustness through redundancy, biological systems employ functional degeneracy and promiscuous activities that enable evolutionary innovation [26].

This philosophical distinction manifests practically in pathway design. Nature typically employs divergent strategies where a minimal set of precursors gives rise to extensive structural diversity, as seen in terpene biosynthesis where a single precursor like farnesyl diphosphate is transformed into structurally distinct products like (+)-5-epi-aristolochene and (-)-premnaspirodiene by highly similar enzymes [1]. In contrast, traditional chemical synthesis more commonly employs convergent approaches, as evidenced by the numerous synthetic routes to staurosporinone that converge to a single product [1].

Hybrid synthesis planning represents a middleware position that respects nature's catalytic efficiency while acknowledging the practical scope of synthetic methodology. By algorithmically identifying opportunities where enzymatic selectivity can replace complex synthetic sequences for introducing stereochemistry or achieving challenging regioselectivity, these tools operationalize the strategic integration of both approaches [23]. The case of sitagliptin synthesis exemplifies this principle, where a transaminase selectively catalyzes formation of the chiral amine from chemically derived pro-sitagliptin, replacing traditional resolution methods [23].

Hybrid synthesis planning algorithms represent a significant advancement in chemical synthesis strategy, enabling systematic exploration of routes that combine the unique strengths of enzymatic and synthetic transformations. Through dual-network architectures, unified scoring metrics, and customizable search strategies, these tools facilitate discovery of more efficient, sustainable, and elegant synthetic pathways that might remain hidden when considering either approach in isolation.

The philosophical implications extend beyond practical efficiency to challenge the traditional dichotomy between natural biosynthetic strategies and human chemical design. By algorithmically identifying optimal integration points between these domains, hybrid planning embodies a more nuanced understanding of synthesis that respects both nature's evolutionary logic and chemists' design intelligence.

As these tools continue to evolve, their integration with experimental validation platforms and expansion to encompass broader reaction spaces will further enhance their utility for pharmaceutical development and industrial chemical synthesis. For researchers seeking to implement these approaches, the choice among available algorithms should be guided by specific research needs: DORAnet offers exceptional customizability for specialized applications, ACERetro provides demonstrated performance advantages in pathway discovery, and the Hybrid Retrosynthetic Search algorithm establishes a robust foundation for balanced enzymatic-synthetic integration.

In the realm of molecular construction, chemists and nature often employ divergent strategies to build complex carbon frameworks. While biosynthetic pathways frequently utilize enzyme-catalyzed, divergent routes from a core set of simple building blocks, synthetic chemists often devise convergent approaches that assemble complex targets from readily available precursors through key strategic bond-forming reactions [1]. Among the synthetic chemist's most valuable tools for carbon-carbon (C-C) bond formation is the Hosomi-Sakurai reaction (HSR), also known as the Sakurai allylation. This transformative reaction, discovered in the 1970s, enables the efficient allylation of carbonyl compounds using nucleophilic allylsilanes catalyzed by Lewis acids [27] [28]. The reaction has become indispensable in synthetic organic chemistry, particularly in the total synthesis of biologically active natural products featuring complex polycyclic architectures with multiple stereogenic centers [27].

The Hosomi-Sakurai reaction exemplifies the synthetic chemist's ability to create molecular complexity through carefully designed, atom-economical processes that often differ fundamentally from nature's biosynthetic machinery. Where natural product biosynthesis might employ tail-to-head terpene cyclizations from isopentenyl diphosphate precursors [1], synthetic chemists can employ the HSR to install key homoallylic alcohol functionalities that serve as versatile handles for further molecular elaboration. This article examines the Hosomi-Sakurai reaction as a case study in synthetic strategy, comparing its applications with natural approaches to molecular construction while providing detailed experimental protocols and performance data to guide researchers in synthetic chemistry and drug development.

Reaction Fundamentals: Mechanism and Historical Context

Historical Development and Key Advantages

The Hosomi-Sakurai reaction was first reported in 1976 as a superior alternative to classical allylation methods using organometallic reagents [27] [28]. The original transformation involved the Lewis acid-promoted reaction of allylsilanes with carbonyl compounds to form homoallylic alcohols [29]. This discovery was significant as it introduced allylsilanes as stable, non-toxic, and readily available nucleophiles that could be handled at room temperature without special precautions—unlike their highly reactive allyl-magnesium, -lithium, or -copper counterparts that require moisture-free conditions and specific temperatures [27] [28].

The key advantages of the Hosomi-Sakurai approach include:

- Functional group tolerance and compatibility with various substrates

- High regioselectivity with electrophiles attacking exclusively at the C3 terminus of the allylsilane [30]

- Quantitative yields with minimal byproduct formation [27]

- Operational simplicity with reactions often proceeding rapidly even at -78°C [27]

Reaction Mechanism

The Hosomi-Sakurai reaction proceeds through a well-established mechanism characterized by the β-silicon effect, where silicon stabilizes adjacent carbocations through hyperconjugation [29] [31]. The reaction begins with Lewis acid activation of the carbonyl compound, making the carbon more electrophilic. Nucleophilic attack by the γ-carbon of the allylsilane generates a silyl-stabilized β-carbocation intermediate. Finally, cleavage of the C-Si bond with concomitant double bond formation yields the homoallylic product [30] [32].

Figure 1: Hosomi-Sakurai Reaction Mechanism. The diagram illustrates the key steps: Lewis acid activation, nucleophilic attack forming a silyl-stabilized carbocation, and desilylation to yield the final product.

The β-silicon effect is crucial to the reaction's success, as silicon stabilizes the developing positive charge at the β-position through hyperconjugative interactions between the C-Si σ-bond and the empty p-orbital of the incipient carbocation [31]. This stabilization lowers the energy of the transition state and facilitates carbon-carbon bond formation. The reaction is highly regioselective, occurring exclusively at the γ-position of the allylsilane, remote from the silicon atom [27].

Experimental Implementation: Protocols and Catalyst Evolution

Standard Experimental Protocol

A typical Hosomi-Sakurai allylation follows this well-established procedure [30]:

Materials:

- Aldehyde substrate (1.0 equiv)

- Anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM) as solvent

- Titanium tetrachloride (TiCl₄, 1.0 equiv) as Lewis acid

- Allyltrimethylsilane (1.5 equiv)

Procedure:

- Add the aldehyde (2.90 mmol) to anhydrous DCM (29.0 mL) under nitrogen atmosphere.

- Cool the solution to -78°C using a dry ice/acetone bath.

- Slowly add TiCl₄ (1.0 equiv) via syringe and stir for 5 minutes at -78°C.

- Add allyltrimethylsilane (1.5 equiv) dropwise and continue stirring at -78°C for 30 minutes.

- Monitor reaction completion by TLC.

- Quench by adding saturated aqueous NH₄Cl solution.

- Dilute with DCM and transfer to a separatory funnel.

- Separate the organic layer and extract the aqueous layer with DCM.

- Combine organic extracts, dry over Na₂SO₄, filter, and concentrate.

- Purify the crude product by flash column chromatography.

This protocol typically affords the homoallylic alcohol in high yield (e.g., 89% as reported) [30]. The low temperature (-78°C) is crucial for controlling selectivity and preventing side reactions.

Evolution of Catalytic Systems

The journey of Hosomi-Sakurai reaction catalysts has progressed remarkably from stoichiometric to catalytic quantities, addressing economic and environmental concerns [33]:

First Generation (Stoichiometric):

- Traditional Lewis acids: TiCl₄, BF₃·OEt₂, SnCl₄, AlCl₃

- Required stoichiometric or near-stoichiometric amounts

- Limitations: tight coordination with alcohol oxygen, poor silicon transfer efficiency

Second Generation (Catalytic Metal Triflates):

- Rare earth metal triflates: Sc(OTf)₃, Yb(OTf)₃, La(OTf)₃

- Advantages: catalytic loading, moisture tolerance

- Limitations: high cost, moisture sensitivity

Third Generation (Economical & Sustainable):

- Inexpensive catalysts: I₂, FeCl₃, InCl₃

- Brønsted acids and heterogeneous catalysts

- Advantages: water tolerance, low cost, recyclability

Recent Innovations:

- Silver-catalyzed asymmetric variants for ketones [29]

- Brønsted acid catalyzed reactions of acetals [29]

- o-Benzenedisulfonimide as reusable Brønsted acid catalyst [29]

Table 1: Catalyst Evolution in Hosomi-Sakurai Reactions

| Catalyst Generation | Representative Examples | Typical Loading | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Generation | TiCl₄, BF₃·OEt₂, SnCl₄ | Stoichiometric | High reactivity | Moisture sensitivity, waste generation |

| Second Generation | Sc(OTf)₃, Yb(OTf)₃ | 5-30 mol% | Moisture tolerance, catalytic | High cost |

| Third Generation | I₂, FeCl₃, Bi(OTf)₃ | 5-30 mol% | Low cost, green credentials | Variable substrate scope |

| Recent Advances | Ag(I) complexes, TMSOTf | 1-10 mol% | Asymmetric induction, mild conditions | Limited applicability |

Multicomponent Hosomi-Sakurai Reactions

Recent developments have expanded the HSR to multicomponent reactions, incorporating aldehydes, trimethylsilyl ethers, and allyltrimethylsilane to generate homoallyl ethers [34]. This approach is particularly valuable for diversity-oriented synthesis and incorporates bio-based starting materials, aligning with green chemistry principles. However, studies have revealed significant challenges with complex aliphatic aldehydes, where yields remain low compared to activated aromatic aldehydes like 6-bromopiperonal (91% yield) [34]. Catalyst screening has demonstrated the superiority of TMSOTf for these transformations, with alternatives like Bi(OTf)₃ and iodine showing minimal reactivity [34].

Performance Analysis: Comparative Data Across Substrates and Conditions

Substrate Scope and Limitations

The Hosomi-Sakurai reaction demonstrates remarkable versatility across diverse electrophilic substrates while maintaining certain selectivity patterns:

High Reactivity Substrates:

- Acetals and ketals: Convert to homoallyl ethers in high yields [33]

- Aliphatic, alicyclic, and aromatic aldehydes: Form homoallylic alcohols efficiently [27]

- Activated aromatic aldehydes (e.g., 6-bromopiperonal): Excellent yields (91%) [34]

Moderate Reactivity Substrates:

- Ketones: Require more forceful conditions

- α,β-unsaturated aldehydes: React at carbonyl group [30]

- α-Alkoxyaldehydes: Exhibit lower yields due to side reactions [34]

Low Reactivity/Selectivity Challenges:

- α,β-unsaturated ketones: May undergo conjugate addition [30]