Directed Evolution of Biosynthetic Enzymes: Engineering the Next Generation of Biocatalysts for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the directed evolution of biosynthetic enzymes.

Directed Evolution of Biosynthetic Enzymes: Engineering the Next Generation of Biocatalysts for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the directed evolution of biosynthetic enzymes. It covers the foundational principles of mimicking natural selection in the laboratory to engineer enzymes with enhanced properties. The scope includes an exploration of key methodologies for generating genetic diversity and screening improved variants, a practical guide to troubleshooting and optimizing evolution campaigns, and a critical analysis of validated success stories and quantitative outcomes from the literature. By synthesizing current strategies and real-world applications, this review aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to harness directed evolution for creating efficient biocatalysts that can streamline the synthesis of complex therapeutic molecules.

The Principles and Promise of Directed Evolution in Bioscience

Directed evolution is a transformative protein engineering technology that harnesses the principles of Darwinian evolution—iterative cycles of genetic diversification and selection—within a laboratory setting to tailor proteins for specific, human-defined applications [1]. This forward-engineering process compresses geological timescales of natural evolution into weeks or months by intentionally accelerating mutation rates and applying user-defined selection pressure [1]. The profound impact of this approach was formally recognized with the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded to Frances H. Arnold for establishing directed evolution as a cornerstone of modern biotechnology and industrial biocatalysis [1].

The primary strategic advantage of directed evolution lies in its capacity to deliver robust solutions without requiring detailed a priori knowledge of a protein's three-dimensional structure or its catalytic mechanism [1]. This capability allows it to bypass the inherent limitations of rational design, which relies on a predictive understanding of sequence-structure-function relationships that is often incomplete [2] [1]. By exploring vast sequence landscapes through mutation and functional screening, directed evolution frequently uncovers non-intuitive and highly effective solutions that would not have been predicted by computational models or human intuition [1].

Today, this technology is routinely deployed across pharmaceutical, chemical, and agricultural industries to create enzymes and proteins with properties optimized for performance, stability, and cost-effectiveness [1]. For researchers focused on biosynthetic enzymes, directed evolution offers powerful methodology to optimize enzymes for producing valuable compounds, including sustainable biofuels and complex plant natural products [3] [4].

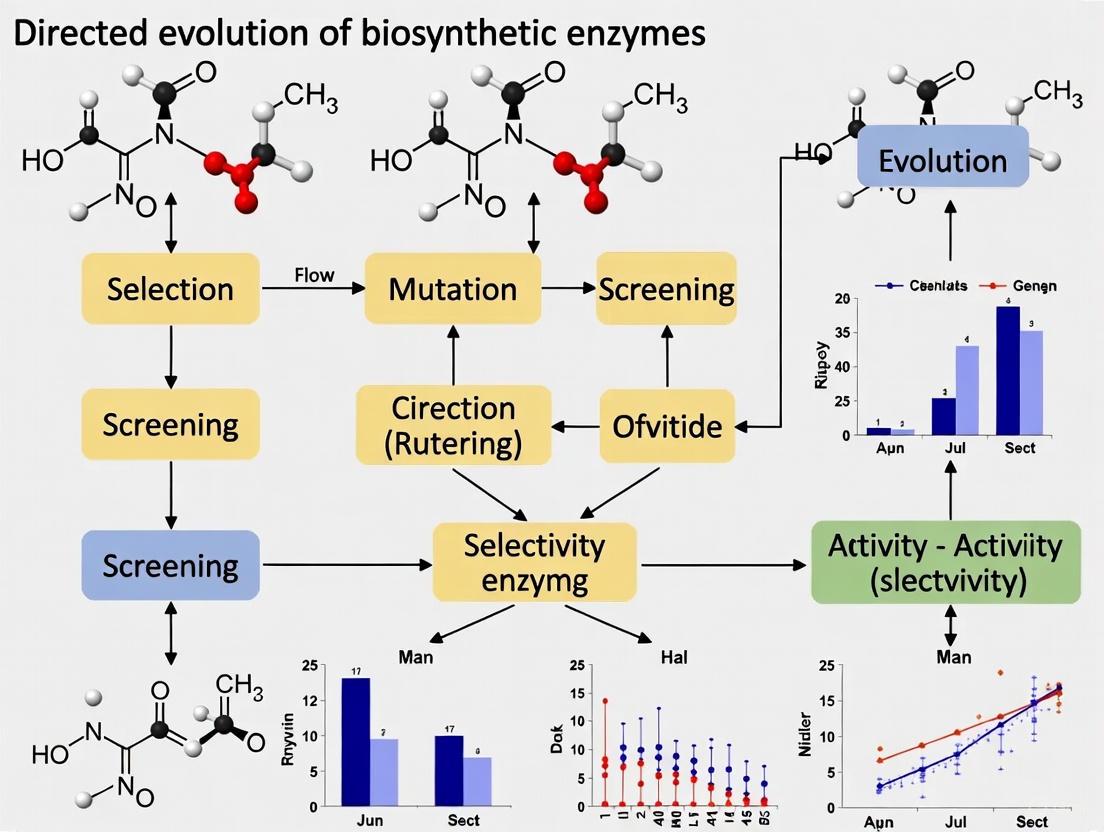

Core Methodology: The Directed Evolution Cycle

At its core, directed evolution functions as a two-part iterative engine, relentlessly driving a protein population toward a desired functional goal [1]. The basic workflow involves iterative rounds of (1) genetic diversification to create a library of protein variants, and (2) screening or selection to identify improved variants [5] [1]. These "winning" variants then serve as the template for subsequent rounds of evolution, allowing beneficial mutations to accumulate [1].

Step 1: Generating Genetic Diversity

The creation of a diverse library of gene variants is the foundational step that defines the boundaries of explorable sequence space [1]. The quality, size, and nature of this diversity directly constrain potential outcomes [1]. Several methods have been developed, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Random Mutagenesis Techniques

Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) is the most established method, introducing random mutations across the entire gene [2] [1]. This technique uses modified PCR conditions—employing polymerases without proofreading capability, creating dNTP imbalances, and adding manganese ions (Mn²âº)—to reduce replication fidelity [1]. The mutation rate is typically tuned to 1-5 base mutations per kilobase, resulting in approximately one or two amino acid substitutions per protein variant [1]. A significant limitation is that epPCR is not truly random; it exhibits transition/transversion bias and can only access approximately 5-6 of the 19 possible alternative amino acids at any given position due to genetic code degeneracy [1].

Recombination-Based Methods

DNA Shuffling (or "sexual PCR") more closely mimics natural recombination by fragmenting parent genes with DNaseI and reassembling them without primers [1]. This allows fragments from different templates to overlap and prime each other, creating chimeric genes with novel mutation combinations [1]. Family Shuffling extends this concept using homologous genes from different species, accessing nature's standing variation to explore broader, functionally relevant sequence space [1]. These methods require substantial sequence homology (typically 70-75% identity) for efficient reassembly [1].

Focused and Semi-Rational Mutagenesis

Site-Saturation Mutagenesis (SSM) comprehensively explores all 19 possible amino acid substitutions at targeted positions [2] [1]. This approach is particularly valuable when structural or functional information identifies "hotspot" residues, creating smaller, higher-quality libraries that deeply interrogate specific regions [1]. SSM can be used to target active site residues or regions identified from prior random mutagenesis rounds [6].

Step 2: Screening and Selection Strategies

Identifying improved variants from libraries dominated by neutral or non-functional mutants represents the primary bottleneck in directed evolution [1]. The screening method's throughput and quality must match the library size, with success dictated by the principle "you get what you screen for" [1].

Screening involves individual evaluation of each library member [1]. Selection establishes conditions where desired function directly couples to host organism survival or replication, automatically eliminating non-functional variants [1]. Selections handle larger libraries with less effort but provide less quantitative data and can be prone to artifacts [1].

Common Screening Platforms

- Plate-Based and Colony Screening: Host cells expressing enzyme libraries are grown on solid medium or in multi-well plates [1]. Activity is detected using colorimetric or fluorometric substrates that produce visible signals [1]. For example, colonies expressing active proteases form clear halos on milk-agar plates due to casein degradation [1].

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Enables ultra-high-throughput screening (up to 10⸠variants per day) when activity can be linked to fluorescence [2].

- Mass Spectrometry-Based Methods: Provide high-throughput screening without requiring specific substrate properties, useful for detecting small molecules like hydrocarbons [2].

Advanced Methodologies and Recent Innovations

Machine Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution

Traditional directed evolution can be inefficient when mutations exhibit non-additive (epistatic) behavior [6]. Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) represents a cutting-edge approach that leverages machine learning to navigate complex fitness landscapes more efficiently [6] [5]. ALDE alternates between wet-lab experimentation and computational modeling, using uncertainty quantification to prioritize which variants to test in each iteration [6].

In a recent application, ALDE optimized five epistatic residues in a protoglobin active site for a non-native cyclopropanation reaction [6]. Within three rounds (exploring only ~0.01% of the design space), the method improved product yield from 12% to 93% with excellent diastereoselectivity [6]. The optimal mutation combination was not predictable from initial single-mutation screens, demonstrating ALDE's ability to navigate challenging epistatic landscapes [6].

Artificial Enzymes with Non-Canonical Amino Acids

Recent breakthroughs enable creation of designer enzymes incorporating genetically encoded non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) with abiological catalytic functions [7]. This approach significantly expands the catalytic repertoire for non-native transformations [7]. A key innovation involves integrating ncAA biosynthesis with genetic code expansion, allowing in situ production and incorporation of catalytic ncAAs like S-(4-aminophenyl)-L-cysteine (pAPhC) [7].

After directed evolution, these artificial enzymes catalyze enantioselective Friedel-Crafts alkylation with excellent enantioselectivity (up to 95% e.e.) and yields (up to 98%) [7]. This strategy provides access to diverse artificial enzyme libraries with xenobiotic catalytic moieties, expanding the biocatalyst toolbox for abiological transformations [7].

In Situ Directed Evolution

Advanced techniques now enable targeted protein diversification within specific cellular compartments [8]. CRISPR-Cas9-based approaches generate mutant protein libraries targeted to specific organelles, allowing directed evolution in physiologically relevant environments [8]. This methodology validates protein function directly in desired subcellular locations, potentially accelerating engineering of proteins that must function in specific cellular contexts [8].

Technical Reference Tables

Comparison of Diversity Generation Methods

| Technique | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR [2] [1] | Random point mutations via low-fidelity PCR | Easy to perform; no prior knowledge needed | Mutagenesis bias; limited amino acid coverage | Initial diversification; stability improvements [2] [1] |

| DNA Shuffling [1] | Recombination of gene fragments | Mimics natural recombination; combines beneficial mutations | Requires high sequence homology (>70%) | Recombining beneficial mutations from different variants [1] |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis [2] [1] | All amino acids tested at targeted positions | Comprehensive exploration of specific sites | Limited to predefined positions | Active site engineering; optimizing key residues [2] [6] |

| RAISE [2] | Random short insertions and deletions | Generates indels across sequence | Introduces frameshifts; limited to few nucleotides | Beta-lactamase evolution [2] |

| Orthogonal Replication Systems [2] | In vivo mutagenesis using engineered DNA polymerases | Targeted mutagenesis in living cells | Relatively low mutation frequency | Dihydrofolate reductase evolution [2] |

Comparison of Screening and Selection Methods

| Method | Throughput | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plate Screening [2] [1] | Medium (10²-10³) | Colorimetric/fluorimetric assay in multi-well plates | Quantitative data; automation possible | Limited throughput; requires detectable signal [2] [1] |

| FACS-Based Screening [2] | High (10â·-10â¸/day) | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting | Ultra-high throughput; sensitive | Requires fluorescence linkage [2] |

| Mass Spectrometry [2] | Medium to High | Direct detection of substrates/products | No need for specialized substrates; versatile | Equipment cost; throughput limitations |

| Phage Display [2] | High (10â¹-10¹¹) | Binding selection via displayed proteins | Extremely high library sizes | Limited to binding proteins [2] |

| QUEST [2] | High | Coupling reaction to cell survival | Powerful positive selection | Limited to specific substrate types [2] |

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Directed Evolution | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| NNK Degenerate Codon Primers [6] | Site-saturation mutagenesis to cover all amino acids | NNK covers all 20 amino acids with 32 codons; reduces stop codons |

| epPCR Kits [1] | Introduce random mutations across gene sequence | Tunable mutation rates (typically 1-5 mutations/kb) via Mn²⺠concentration |

| Orthogonal Translation System [7] | Incorporates non-canonical amino acids | Requires engineered aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pair |

| Fluorescent Substrates [2] [1] | Enable high-throughput activity screening | Must correlate with target activity; can use surrogate substrates |

| Selection Plasmids [2] | Link desired activity to survival markers | Enables growth-based selection rather than screening |

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Directed Evolution

Q1: How do I address low library diversity in error-prone PCR?

The most common causes of low diversity are suboptimal Mn²⺠concentration and incorrect dNTP ratios [1]. Titrate MnCl₂ between 0.1-0.5 mM and create dNTP imbalances by reducing one dNTP while increasing others [1]. Remember that epPCR has inherent biases—it primarily generates transitions rather than transversions and accesses only 5-6 of 19 possible amino acid substitutions at each position [1]. For more comprehensive coverage, consider combining epPCR with other methods like saturation mutagenesis [1].

Q2: What screening throughput do I need for my library size?

The required throughput depends on library size and the frequency of improved variants [1]. For random mutagenesis libraries with mutation rates of 1-3 mutations/gene, screening 10³-10ⴠvariants is typically sufficient to find improvements [1]. For saturation mutagenesis at single positions (~20 variants), complete screening is feasible [1]. However, multi-site saturation libraries grow exponentially (20⿠for n positions), requiring efficient pre-screening or selection methods [1]. As a guideline, your screening capacity should exceed your library size by at least 3-5 fold to ensure adequate sampling.

Q3: How can I overcome epistasis (non-additive mutation effects)?

Epistasis is a major challenge where mutation effects depend on genetic background [6]. Traditional DE approaches that recombine individually beneficial mutations often fail due to negative epistasis [6]. Machine learning-assisted approaches like ALDE specifically address this by modeling higher-order interactions [6] [5]. Alternatively, use family shuffling to recombine naturally evolved sequences that have already been optimized for compatibility [1], or employ in vivo continuous evolution systems that allow mutations to accumulate in a single genetic background [2].

Q4: What are the typical costs and timelines for a directed evolution campaign?

Costs vary significantly based on library size and screening method [9]. For site-saturation mutagenesis, pooled delivery of all single-substitution variants costs approximately $100-150 per site, while individual variant delivery in plates costs $800-1,200 per site [9]. A typical GFP optimization project might cost around $10,000 [9]. Turnaround times are typically 4-6 weeks for gene libraries and 8 weeks for cloned libraries [9]. A complete directed evolution campaign with 3-4 rounds typically requires 3-6 months, depending on screening throughput [1].

Q5: How can I improve thermostability while preserving enzyme activity?

Thermostability engineering presents a challenge because mutations that enhance stability often reduce activity [9]. From customer examples using site-saturation mutagenesis, beneficial substitutions can come from different chemical groups (polar, uncharged, etc.), making them hard to predict rationally [9]. A successful strategy involves screening for stability (e.g., using thermal challenge) while subsequently assaying positive hits for retained activity [1]. Focus on surface residues for stability mutations and active-site adjacent residues for activity optimization, though beneficial mutations can sometimes occur in unexpected locations [9].

For researchers engineering biosynthetic enzymes, directed evolution provides a powerful methodology to optimize enzymes for industrial production of valuable compounds [3] [4]. Successful implementation requires careful planning of both diversity generation and screening strategies, with methods matched to project goals and resources [1]. Emerging approaches like machine learning-assisted directed evolution [6] and artificial enzymes with non-canonical amino acids [7] are pushing the boundaries of what's possible, enabling creation of biocatalysts with unprecedented functions and efficiency.

The integration of directed evolution with biosynthetic pathway engineering promises to accelerate development of sustainable production platforms for biofuels [3], plant natural products [4], and pharmaceutical compounds, ultimately expanding the toolbox of biocatalysts available for solving challenging problems in synthetic biology and industrial biotechnology.

Troubleshooting Guide: Directed Evolution in Enzyme and Pathway Engineering

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How can I improve the success rate of my directed evolution campaigns when working with complex drug substrates?

Success hinges on two main factors: the quality of your genetic library and the effectiveness of your screening method [1]. For new-to-nature substrates, a semi-rational approach combining computational design with directed evolution is often most effective [10]. If your initial libraries are not yielding improvements, consider shifting from purely random mutagenesis (like error-prone PCR) to methods that offer more focused diversity, such as site-saturation mutagenesis of predicted active-site residues [1] [2]. Furthermore, ensure your high-throughput screen accurately reflects your final desired activity, as screens using surrogate substrates can sometimes be misleading [2].

2. What is the most common cause of false positives in ultra-high-throughput selection platforms, and how can it be mitigated?

In emulsion-based selection platforms, a common cause of false positives is the recovery of "parasite" variants that survive due to non-specific or alternative activities, rather than the desired function [11]. For example, a polymerase variant might be recovered because it can utilize low levels of endogenous cellular nucleotides instead of the provided unnatural substrate. Mitigation requires careful optimization of selection parameters. A recommended strategy is to use a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach to screen and benchmark factors like cofactor concentration, substrate chemistry, and reaction time using a small, focused library before scaling up [11].

3. Our engineered enzyme performs well in vitro but fails to function in a whole-cell biosynthetic pathway. What could be wrong?

This is a common challenge when integrating engineered components into complex cellular metabolism [10]. The issue often lies in context-dependent factors not present in isolated assays. Key areas to investigate include:

- Cofactor Availability: Ensure your host cell can regenerate the necessary cofactors (e.g., NADH) at a sufficient rate [12].

- Substrate Transport: Verify that your drug synthesis precursor can efficiently enter the cell and reach the engineered enzyme.

- Product Toxicity or Sequestration: The product of your reaction may be toxic to the host cell or may be sequestered or modified by other native enzymes [10].

- Enzyme Solubility and Stability: Re-check that your enzyme is properly folded and stable in the cellular environment.

4. We need to engineer an enzyme for a reaction with no known natural analogue. What are the available strategies?

Creating entirely new catalytic activities is an advanced challenge. One powerful emerging strategy is the design of artificial enzymes using genetically encoded non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) [7]. This involves:

- Biosynthesis and Incorporation: Developing a system for the in-situ biosynthesis and genetic incorporation of an ncAA that harbors a catalytic functional group (e.g., a synthetic mercapto-aniline residue) into a protein scaffold [7].

- Directed Evolution: Once a baseline activity is established, subjecting this designer enzyme to directed evolution to fine-tune its efficiency and selectivity for the target abiological transformation [7].

Key Performance Metrics in Directed Evolution

The table below summarizes typical improvements in catalytic parameters achieved through directed evolution campaigns, providing a benchmark for your projects [12].

| Catalytic Parameter | Average Fold Improvement | Median Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|

kcat (or Vmax) |

366-fold | 5.4-fold |

Km |

12-fold | 3-fold |

kcat/Km |

2548-fold | 15.6-fold |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Directed Evolution Workflow

This protocol outlines the core iterative cycle for evolving improved enzymes [1] [13] [10].

Step 1: Generate Genetic Diversity (Library Generation)

- Method Selection: Choose a mutagenesis method based on your goal and prior knowledge.

- Error-Prone PCR (epPCR): Ideal for introducing random mutations across the entire gene without prior structural knowledge. Tune mutation rate using Mn2+ and unbalanced dNTPs to target 1-5 mutations/kb [1].

- DNA Shuffling: Recombines beneficial mutations from multiple parent genes. Requires >70% sequence homology for efficient crossover [1].

- Site-Saturation Mutagenesis: Targets specific residues to explore all 19 possible amino acids at that position. Use when structural data or previous rounds identify "hotspot" residues [1] [2].

- Library Size: Aim for a library size that your screening method can accommodate. For random approaches, larger libraries are better, but the screening bottleneck is critical [1].

Step 2: Link Genotype to Phenotype (Screening/Selection)

- Screening vs. Selection: Screening involves individually testing variants (e.g., in microtiter plates), while selection couples desired function to host survival [1].

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): For lower-throughput screens (e.g., 104-106 variants), use plate-based assays with colorimetric or fluorometric outputs. For higher throughput (107-109 variants), Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) is preferred if the activity can be linked to a fluorescence signal [2].

- Selection Platform: For the highest throughput, use platforms like phage display or in vitro compartmentalization (e.g., emulsion-based assays) that physically link the protein variant to its encoding DNA [11].

Step 3: Gene Amplification and Iteration

- Isolate the genes from the top-performing variants identified in Step 2.

- Use these improved sequences as the template for the next round of mutagenesis and screening.

- Repeat the cycle until the desired performance level is achieved or no further improvement is observed [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for setting up directed evolution experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kits | Introduce random mutations across the gene of interest. Kits with engineered polymerases (e.g., Mutazyme) offer less biased mutagenesis than Taq-based methods [12] [1]. |

| KAPA Biosystems Polymerases | Examples of commercially available enzymes engineered via directed evolution for enhanced performance in PCR, qPCR, and NGS applications, demonstrating the technology's real-world output [13]. |

| Orthogonal Translation System (OTS) | For incorporating non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs); typically consists of an orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pair that does not cross-react with the host's natural machinery [7]. |

| Fluorogenic/Chromogenic Substrates | Essential for high-throughput screening in microtiter plates or via FACS, providing a detectable signal upon enzyme activity [2] [13]. |

| Microtiter Plates (96-/384-well) | Standard format for medium-throughput screening of enzyme variants in cell lysates or culture supernatants [1]. |

| FACS (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter) | Instrument for ultra-high-throughput screening of cell-surface displayed libraries or intracellular enzymes using fluorescent reporters [2]. |

Workflow and Troubleshooting Visualizations

Directed Evolution Workflow

Troubleshooting No Improved Variants

Core Principles of the Directed Evolution Cycle

What is the "Core Cycle" in directed evolution? The Core Cycle is the fundamental, iterative engine of directed evolution, mimicking Darwinian evolution in a laboratory setting to tailor proteins for specific applications. It consists of two primary phases: (1) the generation of genetic diversity to create a library of protein variants, and (2) the application of a high-throughput screen or selection to identify the rare variants exhibiting improvement in a desired trait. The genes encoding these improved variants are then isolated and used as the starting material for the next round of evolution, allowing beneficial mutations to accumulate over successive generations [1].

How does directed evolution differ from rational design? The primary strategic advantage of directed evolution lies in its capacity to deliver robust solutions—such as enhanced stability, novel catalytic activity, or altered substrate specificity—without requiring detailed a priori knowledge of a protein's three-dimensional structure or its catalytic mechanism. This allows it to bypass the inherent limitations of rational design, which relies on a predictive understanding of sequence-structure-function relationships that is often incomplete. By exploring vast sequence landscapes, directed evolution frequently uncovers non-intuitive and highly effective solutions [1].

Phase 1: Generating Genetic Diversity - Methodologies and Protocols

Library Creation Techniques

Creating a diverse library of gene variants is the foundational step that defines the boundaries of explorable sequence space. The choice of method is a strategic decision that shapes the entire evolutionary search [1].

Table 1: Methods for Generating Genetic Diversity in Directed Evolution

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Mutation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) | Uses low-fidelity PCR conditions to introduce random point mutations across the gene [1]. | Simple, widely applicable, requires no structural information [1]. | Mutation bias (favors transitions), can only access ~5-6 of 19 possible amino acids per position [1]. | 1-5 base mutations/kb [1]. |

| DNA Shuffling | Homologous recombination of fragments from one or more parent genes to create chimeric variants [1]. | Combines beneficial mutations, mimics sexual recombination [1]. | Requires high sequence homology (>70-75%) for efficient reassembly [1]. | Not applicable (recombination). |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | Targets a specific codon to generate all 19 possible amino acid substitutions at that position [1]. | Exhaustively explores functional role of a specific residue, creates high-quality focused libraries [1]. | Requires prior knowledge or hypothesis about important residues [1]. | All amino acids at a single site. |

Advanced and Semi-Rational Protocols

How can I design smarter libraries to improve efficiency? To increase the efficiency of the search process, you can limit sequence space exploration to favorable amino acid exchanges. While predicting beneficial mutations is difficult, identifying and excluding destabilizing mutations is more straightforward. A proven protocol involves:

- Computational Filtering: Use a computational stability prediction tool, such as the Cartesian ΔΔG protocol in the Rosetta Protein Modeling Suite, to calculate the predicted free energy change (ΔΔG) for all possible single amino acid substitutions in your parent gene.

- Library Design: When designing your library, exclude all mutations that are predicted to be highly destabilizing (e.g., those with a ΔΔG above a set threshold, such as -0.5 Rosetta Energy Units). This allows you to screen a smaller, more focused library (e.g., 30% of all possible mutations) without losing beneficial variants [14].

- Targeted Saturation: Focus saturation on residues within a specific radius of the active site or substrate tunnel, applying the stability filter to the resulting variant list [14].

Phase 2: Screening & Selection - Troubleshooting High-Throughput Assays

Choosing the Right Strategy

What is the difference between a screen and a selection, and which should I use? This is a critical distinction. A selection establishes a condition where the desired function is directly coupled to the survival or replication of the host organism (e.g., growth on a toxic substrate or essential nutrient synthesis). Selections can handle extremely large libraries (millions to billions) but can be prone to artifacts and provide little quantitative data. A screen involves the individual evaluation of every library member for the desired property. While lower in throughput, it guarantees every variant is tested and provides valuable quantitative data on performance distribution. The choice depends on your library size and need for quantitative data [1].

Troubleshooting Common Screening Problems

FAQ: My screen has low throughput, creating a bottleneck. What are my options?

- Problem: Throughput of the screening method is mismatched with the size of the library.

- Solution A (Automation): Integrate laboratory automation and biofoundries. Robotic liquid handlers, plate sealers, and high-content screening systems can dramatically increase reproducibility and throughput. One platform demonstrated the construction and testing of 96 variants per round in a fully automated workflow [15].

- Solution B (Machine Learning): Implement machine learning to reduce experimental burden. Protein Language Models (PLMs) can make zero-shot predictions to prioritize the most promising variants for testing, requiring smaller, smarter libraries to be screened [15].

FAQ: I am engineering an enzyme that produces an insoluble or gaseous product (e.g., hydrocarbons). How can I detect activity?

- Problem: The physiochemical properties of the target molecule (e.g., aliphatic hydrocarbons) make detection in vivo challenging.

- Solution: This is a non-trivial challenge. Current research focuses on developing sophisticated biosensors or extraction methods coupled with analytical techniques like GC-MS. Dynamically coupling the abundance of these molecules to cell fitness for a true selection is an area of active development [3].

Integrating Machine Learning and Automation

How can modern computational tools accelerate the Core Cycle? Machine learning (ML) and automation are transforming directed evolution from a purely empirical process to a more predictive one. The integration creates a closed-loop Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle.

- Design: Protein Language Models (PLMs) like ESM-2, trained on vast evolutionary data, can predict high-fitness single mutants from scratch (zero-shot prediction) or design multi-mutant variants at predefined sites [15].

- Build & Test: An automated biofoundry physically constructs the proposed variants (e.g., via automated DNA assembly and transformation) and assays them for function [15].

- Learn: The experimental results are fed back to a supervised ML model (e.g., a multi-layer perceptron) to train a fitness predictor. This model then guides the design of the next, improved set of variants [15]. This approach has been shown to improve enzyme activity by up to 2.4-fold in just four rounds over 10 days [15].

Diagram 1: The machine learning-augmented Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle for accelerated directed evolution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Taq Polymerase (non-proofreading) | Essential enzyme for Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) to introduce random mutations [1]. | Lacks 3' to 5' exonuclease activity, leading to higher error rates during amplification [1]. |

| Manganese Ions (Mn²âº) | Critical additive for epPCR to further reduce fidelity of DNA polymerase [1]. | Concentration can be titrated to tune the mutation rate [1]. |

| DNase I | Enzyme used in DNA Shuffling to randomly fragment parent genes into small pieces for recombination [1]. | Creates fragments of 100-300 bp for subsequent reassembly [1]. |

| Oligo Pools / Gene Fragments | Custom DNA oligonucleotides for semi-rational library construction or full gene synthesis [14]. | Allows for precise control over randomized positions; used in stability-informed library design [14]. |

| Colorimetric/Fluorogenic Substrates | Enable high-throughput screening in microtiter plates by generating a detectable signal upon enzyme activity [1]. | Readily quantified by plate readers; essential for quantitative screening [1]. |

| Rosetta Software Suite | Computational tool for protein modeling and predicting stability changes (ΔΔG) upon mutation [14]. | Used to filter out destabilizing mutations prior to library construction [14]. |

| Triheptadecanoin | Triheptadecanoin | High-Purity Lipid Research Standard | High-purity Triheptadecanoin for research. A defined triglyceride standard for lipid metabolism & analytical method development. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| 4-Cyanoindole | 4-Cyanoindole, CAS:16136-52-0, MF:C9H6N2, MW:142.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram 2: The classic Directed Evolution Core Cycle of mutagenesis, screening, and amplification.

Engineering for Improved Activity, Selectivity, Stability, and Solubility

In the field of directed evolution of biosynthetic enzymes, engineering proteins for enhanced activity, selectivity, stability, and solubility is paramount for developing efficient microbial cell factories and viable industrial bioprocesses [3] [16] [10]. These properties are often interconnected; enhancing one can impact the others, requiring a balanced engineering approach [16] [17]. Directed evolution, which mimics natural selection through iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening, is a powerful tool for achieving these optimizations without requiring exhaustive prior knowledge of the enzyme's structure [10] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Enzyme Activity

Problem: Your enzyme variant shows low catalytic activity after a round of directed evolution. Question: What are the common causes for low enzyme activity and how can I resolve them?

- Potential Cause: Disruption of Active Site Residues. Mutations near the catalytic active site are highly likely to impair activity [17].

- Solution: Focus mutagenesis efforts on residues outside a certain radius from the active site. Utilize semi-rational design tools like CAST (Combinatorial Active-Site Saturation Test) to target residues lining the active site without completely disrupting its core architecture [18].

- Potential Cause: Reduced Solubility or Expression. The protein may be misfolding or aggregating, leading to a lower concentration of functional enzyme [17].

- Solution: Co-express with chaperones or use a different host strain. Screen for improved solubility using methods like yeast surface display (YSD) and prioritize mutations that are predicted to enhance solubility without sacrificing function, such as those found in surface-exposed residues [17].

- Potential Cause: Ineffective Library or Screen. Your screening method may not be capable of detecting the desired improvement, or the library diversity might be insufficient [3].

- Solution: Ensure your high-throughput screening assay is sensitive enough to detect small improvements in activity. Consider using a selection-based system if possible, or switch to a machine-learning guided approach that can predict functional variants from larger sequence spaces [18] [19].

Poor Enzyme Selectivity

Problem: An evolved enzyme produces unwanted by-products or has incorrect stereoselectivity. Question: How can I improve the selectivity of my enzyme for a desired product?

- Potential Cause: Broad Substrate Specificity. The enzyme's active site may be too promiscuous [20].

- Solution: Employ regio- or stereo-selectivity screens. Use structure-guided methods like ISM (Iterative Saturation Mutagenesis) on residues in the access tunnels or substrate-binding pockets to create steric or electronic constraints that favor the binding and transformation of the desired substrate [18] [20].

- Potential Cause: Suboptimal Reaction Conditions. Factors like pH, temperature, or solvent can influence selectivity [20].

- Solution: Optimize the reaction buffer and conditions. Even an evolved enzyme may require specific conditions to achieve maximum selectivity.

Reduced Stability or Solubility

Problem: Your engineered enzyme precipitates, degrades easily, or is inactive at required temperatures or pH. Question: How can I enhance the stability and solubility of my enzyme without completely losing activity?

- Potential Cause: Trade-off Between Stability and Activity. Many mutations that increase solubility can decrease catalytic activity, and vice-versa [17].

- Solution: Use deep mutational scanning to map solubility and fitness landscapes. Machine learning models trained on this data can predict "Pareto optimal" mutations that improve solubility with minimal impact on activity, achieving up to 90% accuracy [17].

- Potential Cause: Marginally Stable Native State. The wild-type enzyme may be inherently unstable under process conditions [17].

- Solution: Incorporate "back-to-consensus" mutations. Replace amino acids in your enzyme sequence with the most common residues found in its homologs (the consensus sequence), as these often improve stability [17] [18]. For thermostability, use epPCR (error-prone PCR) at higher temperatures and screen for retained activity [10] [18].

Table 1: Successfully Engineered Enzymes and Property Improvements

| Enzyme Name | Engineering Goal | Method Used | Key Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| McbA (amide synthetase) | Activity / Substrate Scope | ML-guided Cell-Free Expression | 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity for 9 pharmaceuticals [19] | |

| Levoglucosan Kinase (LGK) | Solubility & Activity | Deep Mutational Scanning | Identified Pareto-optimal mutations for solubility with 90% activity prediction accuracy [17] | |

| TEM-1 β-lactamase | Solubility & Activity | Deep Mutational Scanning | ~5% of all single missense mutations improved solubility [17] | |

| Cytochrome P450 (Alkane Hydroxylase) | Activity | Directed Evolution | Evolved a highly active, self-sufficient soluble hydroxylase [10] |

Table 2: High-Throughput Solubility and Fitness Screening Methods

| Method Name | Principle | Throughput | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Surface Display (YSD) | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting detects folded proteins on yeast surface [17] | High | Eukaryotic expression system, detecting soluble expression [17] | May not reflect solubility in bacterial hosts [17] |

| Tat Pathway Selection | Bacterial twin-arginine translocation exports only folded proteins to periplasm [17] | High | Bacterial expression, genetic selection (no FACS needed) [17] | Requires fusion protein; potential for false positives/negatives [17] |

| Cell-Free Expression & Assay | In vitro transcription/translation followed by direct functional assay [19] | Very High | Rapid, ML-guided iterative testing without cloning [19] | May lack cellular context (e.g., chaperones) [19] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Traditional Directed Evolution Workflow Using epPCR

This is a foundational method for introducing random mutations and screening for improved traits [10] [18].

- Diversity Generation (epPCR): Set up error-prone PCR reactions on your target gene using conditions that promote a low, controlled error rate (e.g., using Mn2+ ions). Aim for a mutation rate of 1-3 amino acid substitutions per gene.

- Library Construction: Clone the mutated PCR fragments into an appropriate expression vector. Transform the library into a bacterial host (e.g., E. coli) to create a variant library.

- Screening/Selection: Plate the transformed cells and pick colonies into 96- or 384-well plates for expression. Lyse the cells and assay for the desired enzymatic property (e.g., activity, selectivity).

- Hit Identification: Identify the top-performing variants from the screen.

- Iteration: Use the best hit(s) as the template(s) for the next round of epPCR. Repeat steps 1-4 until the desired improvement is achieved.

Protocol 2: Machine-Learning Guided Directed Evolution in a Cell-Free System

This modern, high-throughput protocol accelerates the engineering cycle [19].

- Design:

- Select target residues for mutagenesis based on structure or homology.

- Design primers for site-saturation mutagenesis.

- Build (Cell-Free DNA Assembly):

- Perform PCR with primers containing nucleotide mismatches to introduce mutations.

- Digest the parent plasmid with DpnI.

- Use intramolecular Gibson assembly to form the mutated plasmid.

- Perform a second PCR to amplify Linear DNA Expression Templates (LETs). This entire step can be done in a single day for thousands of variants.

- Test (Cell-Free Expression and Assay):

- Express the mutated proteins directly from the LETs using a cell-free gene expression (CFE) system.

- Directly perform the functional enzyme assay in the cell-free reaction mixture or a derived lysate.

- Learn (Machine Learning Model Training):

- Collect the sequence-function data for all tested variants.

- Use this data to train a supervised machine learning model (e.g., augmented ridge regression).

- The model predicts the fitness of higher-order mutants, guiding the selection of templates for the next "Design" round.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function in Workflow | Specific Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Diversity Generation | Introduces random mutations across the gene of interest. Kits often include optimized buffers with Mn2+ to control mutation rate [18]. |

| DNA Shuffling Reagents | Diversity Generation | Recombines beneficial mutations from multiple parent genes to explore sequence space more efficiently [18]. |

| Yeast Surface Display Kit | Screening | Identifies folded, soluble protein variants via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [17]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis System | Expression & Assay | Enables rapid, high-throughput expression and testing of enzyme variants without cloning or living cells [19]. |

| Methylation-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes | Cloning | Enzymes like DpnI are used to digest the methylated parent plasmid template after PCR, enriching for newly synthesized mutated DNA [19]. |

| E. coli dam-/dcm- Strains | Cloning | Host strains lacking methylation systems, used to produce plasmid DNA that is not blocked from digestion by methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: I am starting with a new enzyme and have no structural data. What is the best directed evolution strategy? Begin with random mutagenesis methods like error-prone PCR (epPCR) or DNA shuffling. These require no prior structural knowledge. Pair this with a robust high-throughput screen for your desired property. As you collect data, you can transition to more rational approaches [10] [18].

FAQ 2: How do I balance the trade-off between improving enzyme solubility and maintaining its catalytic activity? This is a classic challenge. Focus on mutations that are evolutionarily conserved and located far from the active site. These have a higher probability of improving solubility without disrupting function. Utilizing deep mutational scanning and machine learning models can help identify these Pareto-optimal mutations efficiently [17].

FAQ 3: What are the biggest challenges in applying directed evolution to hydrocarbon-producing enzymes? A major challenge is detection. Hydrocarbon products are often insoluble, gaseous, or chemically inert, making it difficult to design sensitive high-throughput screens or growth-coupled selections that dynamically link product abundance to cell fitness [3].

FAQ 4: When should I use a screening approach versus a selection approach? Use screening when you need to quantify a multi-parametric improvement (e.g., activity under specific conditions) or when no growth-coupled selection is available. Use selection when you can directly link enzyme function to host cell survival (e.g., antibiotic resistance). Selections allow you to search much larger libraries (>>106 variants) with less effort [3] [10].

FAQ 5: How is machine learning (ML) transforming directed evolution? ML is revolutionizing the field by using data from initial rounds of evolution to predict the fitness of unsampled variants. This drastically reduces the experimental screening burden and helps avoid local optima by identifying beneficial mutations that have synergistic (epistatic) effects [18] [19]. Tools like AlphaFold for structure prediction further provide structural context for semi-rational design [3].

A Toolkit for Enzyme Engineering: Methods and Real-World Applications

How do random mutagenesis methods integrate into a directed evolution workflow for biosynthetic enzymes?

Directed evolution is a powerful protein engineering technique that mimics natural selection in a laboratory setting to tailor enzymes for specific, human-defined applications, such as creating novel biocatalysts for drug synthesis [1]. The process functions as an iterative, two-part cycle [1]:

- Library Generation: Creating a diverse population of gene variants (a "library").

- Screening/Selection: Identifying the rare variants with improved properties (e.g., enhanced stability, novel activity).

Random mutagenesis is a foundational strategy for the first step, especially when structural information about the enzyme is unavailable [22]. These "sequence agnostic" methods allow for mutation at any position within the gene, exploring a wide sequence landscape to find non-intuitive and highly effective solutions that computational models might miss [1]. For drug development professionals, this is crucial for engineering enzymes with altered substrate specificity or improved efficiency, which can help reduce the complex and costly synthesis of small-molecule therapeutics, addressing issues of "financial toxicity" [12].

The two primary random mutagenesis methods discussed in this guide are Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) and Mutator Strains. This technical support center is designed to help you troubleshoot common issues with these methods to ensure the success of your directed evolution campaigns.

Troubleshooting FAQ

Why is my mutation frequency too low or too high in error-prone PCR?

Achieving the target mutation frequency is critical for a successful library. A low frequency yields insufficient diversity, while a high frequency can overload the enzyme with deleterious mutations.

- Problem: Mutation frequency is too low.

- Solutions:

- Adjust divalent cations: Systematically increase the concentration of MnClâ‚‚ (a common additive to reduce polymerase fidelity) or MgClâ‚‚ (which stabilizes non-complementary base pairs) in your reaction [23] [12].

- Unbalance dNTPs: Use a biased or unbalanced dNTP mixture to promote misincorporation by the polymerase [23] [12].

- Increase cycles/change polymerase: Increase the number of PCR cycles or use an engineered error-prone polymerase with inherently low fidelity, such as Mutazyme [12].

- Problem: Mutation frequency is too high.

- Solutions:

The following workflow provides a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving issues with mutation frequency in epPCR:

What are the common pitfalls when using bacterial mutator strains, and how can I avoid them?

Mutator strains, such as E. coli XL1-Red, are E. coli cells deficient in multiple DNA repair pathways (e.g., mutS, mutD, mutT), leading to a permanently elevated genomic mutation rate [24] [22].

- Problem: The host strain becomes sick and has low transformation efficiency or poor viability over time.

- Solution: This is an inherent issue. The progressive accumulation of deleterious mutations in the host genome reduces its fitness [25]. The solution is to use fresh, newly transformed cells for each mutagenesis experiment and avoid prolonged cultivation or serial passaging. Propagate your plasmid for only a limited number of generations before extracting the mutant library [22].

- Problem: Low mutation frequency in the recovered plasmid library.

- Solution: The standard mutation rate for strains like XL1-Red is relatively low (approximately 0.5 mutations per kilobase) [24]. Ensure you are allowing sufficient time for mutations to accumulate. Cultivation for 24-48 hours may be required to introduce multiple mutations. For higher mutation rates, consider combining this method with a second round of epPCR.

- Problem: Accumulation of "amnesic" mutations that reduce general host fitness and adaptability.

- Solution: This is a fundamental trade-off. Mutator strains rapidly specialize in their current environment but pay a cost in genetic "amnesia," making them less robust to new challenges [25]. This is less of a concern for a single, focused directed evolution campaign but should be considered if the evolved enzyme needs to function in multiple hosts or complex environments.

How do I choose between error-prone PCR and mutator strains for my project?

The choice between these two methods depends on your project's goals, timeline, and technical constraints. The following table provides a direct comparison to guide your decision.

| Feature | Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) | Mutator Strains |

|---|---|---|

| Mutation Rate | Tunable (1-20 mutations/kb [23]); can be very high. | Fixed, relatively low (~0.5 mutations/kb [24]). |

| Experimental Timeline | Fast (several hours for the PCR reaction). | Slow (requires cell cultivation over 24-48 hours [24]). |

| Technical Handling | Requires in vitro DNA manipulation, post-PCR processing, and cloning. | Simple protocol; transform, propagate, and recover plasmid [22]. |

| Mutation Bias | Biased towards transition mutations [1]. | Mutation spectrum depends on the specific repair pathways inactivated. |

| Primary Limitation | Requires cloning the PCR product back into a vector for expression. | Host fitness declines over time; can't be used for prolonged periods [22] [25]. |

| Best For | Rapid generation of highly diverse libraries from a single gene. | Simple, in vivo mutagenesis without specialized equipment or PCR/cloning steps. |

| Dodecyl acetate | Dodecyl acetate, CAS:112-66-3, MF:C14H28O2, MW:228.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Leu-Leu-OH | Leu-Leu-OH, CAS:3303-31-9, MF:C12H24N2O3, MW:244.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

My Gibson Assembly efficiency is low after cloning the error-prone PCR product. What could be wrong?

Low assembly efficiency is often linked to the quality and quantity of the insert DNA.

- Problem: Non-mutagenic nucleotides from the epPCR reaction are inhibiting the assembly enzyme mix.

- Solution: Always purify your epPCR product before assembly. Use a DNA cleanup kit (e.g., MinElute Reaction Cleanup kit) or perform gel extraction to isolate the mutated gene fragment and remove enzymes, salts, and unused dNTPs [24].

- Problem: Using an error-prone polymerase that leaves uneven ends or damages the DNA termini.

- Solution: If possible, use a polymerase that generates blunt ends or is compatible with subsequent cloning steps. Note that standard Taq polymerase often adds a single, non-templated adenosine (A-overhang) which may complicate cloning strategies.

- Problem: Incorrect insert-to-vector ratio.

- Solution: Precisely quantify your purified epPCR product using a fluorometric method (e.g., PicoGreen/Quantifluor) for accuracy, and follow the recommended molar ratios for your assembly method (e.g., a 2:1 insert-to-vector ratio) [23].

Essential Protocols & Reagents

Detailed Protocol: Error-Prone PCR

This protocol is adapted from standard epPCR methods and can be modified based on the desired mutation rate [23].

1. Reaction Setup:

- In a PCR tube, combine the following reagents to a final volume of 50 µL:

- 5 µL of 10X Error-Prone PCR Buffer (e.g., containing 70 mM MgCl₂) [23]

- 1 µL of 50X dNTP Mix (can be biased, e.g., with higher dATP and dTTP concentrations)

- 1 µL of 10 mM MnCl₂ (optional; titrate from 0.1-0.5 mM final concentration) [23]

- 30 pmol of each forward and reverse primer

- ~10 ng (2 fmol) of template DNA

- 1 µL of Taq polymerase (5 U) or a dedicated error-prone polymerase

- Nuclease-free water to 50 µL

2. PCR Amplification:

- Run the following program in a thermocycler:

- Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 2-3 minutes.

- Cycling (25-35 cycles):

- Denature: 94°C for 30 seconds.

- Anneal: 45-60°C for 30 seconds (use the Tm for your primers).

- Extend: 72°C for 1 minute per kilobase of gene length.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C.

3. Post-Amplification Processing:

- Purify the epPCR product using a commercial PCR purification kit.

- Quantify the yield and proceed with your chosen cloning method (e.g., Gibson Assembly, Golden Gate Assembly) into your expression vector [23].

Detailed Protocol: Mutator Strain Method

This protocol uses E. coli XL1-Red as an example [22].

1. Transformation:

- Transform your purified plasmid containing the target gene into commercially competent E. coli XL1-Red cells according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2. Outgrowth and Library Propagation:

- After transformation, add SOC medium and incubate the cells at 37°C with shaking for 1 hour.

- Plate the entire transformation culture onto a selective LB agar plate (e.g., with ampicillin).

- Incubate the plate at 37°C for 24-48 hours to allow colony formation and mutation accumulation.

3. Plasmid Library Recovery:

- Harvest the cells by scraping the colonies off the plate.

- Isolate the plasmid library from the pooled cells using a standard plasmid miniprep or midiprep kit. This plasmid pool is your mutant library, ready for retransformation into a standard expression strain for screening [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function in Random Mutagenesis | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | A common, low-fidelity polymerase used in epPCR due to its lack of 3'→5' proofreading activity [12]. | Inexpensive but has a mutation bias. Not suitable for applications requiring high fidelity. |

| MnClâ‚‚ (Manganese Chloride) | A critical additive that reduces the fidelity of DNA polymerases by promoting misincorporation of nucleotides [23] [12]. | Concentration must be optimized; too much can be toxic to the reaction or inhibit the polymerase. |

| Mutator Strain (e.g., E. coli XL1-Red) | An in vivo mutagenesis tool. Its defective DNA repair pathways lead to a high spontaneous mutation rate in the host genome and the plasmid it carries [24] [22]. | Host becomes progressively sick; plasmid library must be recovered and moved to a clean strain for expression and screening. |

| dNTP Mix (Unbalanced) | Using non-equimolar ratios of dA/dT/dG/dCTP forces the polymerase to make errors during synthesis [12]. | Different biases can be achieved by varying the ratios of specific dNTPs. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Used for routine cloning steps where high accuracy is required, e.g., amplifying the final mutant gene for stable expression [26]. | Possesses 3'→5' exonuclease (proofreading) activity to remove misincorporated bases. |

| Isobutyl laurate | Isobutyl laurate, CAS:37811-72-6, MF:C16H32O2, MW:256.42 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (-)-Isopulegol | (-)-Isopulegol, CAS:89-79-2, MF:C10H18O, MW:154.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications & Data Interpretation

How effective are these methods in generating improved enzymes?

An analysis of 81 directed evolution campaigns provides quantitative data on the average effectiveness of these methods. The table below summarizes the fold-improvements in key kinetic parameters that can be achieved, often through iterative cycles of mutagenesis and screening [12].

| Kinetic Parameter | Average Fold Improvement | Median Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| kcat (Turnover Number) | 366-fold | 5.4-fold |

| Km (Michaelis Constant) | 12-fold | 3-fold |

| kcat/Km (Catalytic Efficiency) | 2548-fold | 15.6-fold |

Note: The large difference between the average and median for kcat and kcat/Km indicates that while most campaigns achieve modest improvements (reflected by the median), a few exceptionally successful projects can skew the average, demonstrating the tremendous potential of directed evolution [12].

What are some advanced and emerging methods for random mutagenesis?

The field continues to evolve with new methods that offer different advantages.

- Error-Prone Rolling Circle Amplification (epRCA): This one-step isothermal method amplifies a circular plasmid template, and the linear tandem-repeat product can be used directly for E. coli transformation, bypassing the need for restriction enzymes and ligases. It can achieve a high mutation frequency (3-4 mutations/kb) [24].

- In Vivo Continuous Evolution Systems (e.g., OrthoRep, FREP): These advanced platforms use engineered systems in yeast or bacteria to continuously mutate a target gene in vivo over many generations, often with the mutation rate linked to a biosensor for autonomous evolution [27].

- DNA Shuffling: This method involves randomly fragmenting a pool of related genes (e.g., from a first round of epPCR) with DNase I and then reassembling them in a PCR-like process without primers. This "sexual PCR" recombines beneficial mutations from different variants, accelerating evolution [1] [22].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) and saturation mutagenesis (SM)?

A1: Site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) is typically used to introduce a single, specific amino acid change at a predetermined residue. In contrast, saturation mutagenesis (SM) is used to replace a single residue with all or many of the other 19 possible amino acids, creating a local library of variants at that position. When SM is applied to one residue, it is called Site-Saturation Mutagenesis (SSM). When applied to multiple residues simultaneously (e.g., in a CASTing approach), it is known as Combinatorial Saturation Mutagenesis (CSM) [28].

Q2: When should I use a CASTing (Combinatorial Active-Site Saturation Test) approach?

A2: The CASTing approach is a powerful semi-rational strategy used when you have structural information about your enzyme's active site. It involves performing SM on multiple residues that form the active site, either individually or in pairs, to explore the sequence space that directly influences substrate binding, specificity, and catalytic activity. This is particularly useful for altering enzyme selectivity or engineering novel activities without randomizing the entire protein sequence [28].

Q3: Why is my saturation mutagenesis library biased, and how can I avoid it?

A3: Library bias is a common issue where certain amino acids are over-represented while others are missing. The primary causes and solutions are [28]:

- Cause: Genetic Code Degeneracy. Using a standard NNK (N = A/T/G/C; K = G/T) primer mix results in unequal codon distribution. For example, leucine is encoded by 6 codons, while tryptophan is encoded by only 1.

- Solution: Use unbiased codon schemes. Employ methods like the "22c-trick" (using NDT, VHG, and TGG codons mixed in a 12:9:1 ratio) or the "20c-Tang method" (using NDT, VMA, ATG, and TGG codons in a 12:6:1:1 ratio). These methods create libraries where each amino acid is represented by a more equal number of codons, dramatically reducing bias and stopping codon redundancy [28].

Q4: My library size is becoming unmanageably large. How can I design "smarter" libraries?

A4: This is known as the "numbers problem." To create smaller, smarter libraries [28]:

- Use Structural Data: Focus SM on hotspot residues predicted from structural models (e.g., flexible loops, active site residues, substrate channel gates).

- Iterative Saturation Mutagenesis (ISM): Instead of mutating all target residues at once, mutate them in sequential cycles. The best variant from one round becomes the template for the next, accumulating beneficial mutations stepwise.

- Employ Reduced Alphabets: As mentioned in A3, using unbiased codon schemes like NDT (which encodes 12 amino acids) instead of NNK (which encodes all 20) can reduce the theoretical library size while maintaining high chemical diversity.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low Mutagenesis Efficiency or Poor Library Diversity

- Potential Cause: Imperfect PCR conditions, primer quality, or incomplete digestion of the parent template.

- Solutions:

- Verify primer quality (HPLC purification is recommended) and optimize annealing temperatures [28].

- When using restriction enzyme-based cloning methods (e.g., in Golden Gate assembly), ensure complete digestion of the parent plasmid to minimize background carry-over [29].

- Sequence a small number of library clones before large-scale screening to check the quality and diversity of your library [28].

Problem: Screening Reveals No Improved Variants

- Potential Causes: The screening assay is not sensitive enough, the wrong residues were targeted, or beneficial mutations require synergistic combinations.

- Solutions:

- Re-validate your screening or selection assay with known positive and negative controls.

- Re-assess your target residues based on structural data or previous mutational studies.

- Consider a strategy that combines beneficial mutations from initial, smaller libraries. Techniques like Golden Gate assembly allow you to seamlessly recombine mutated gene segments from different libraries (e.g., combining a randomly mutated segment with a site-saturated segment) in a single pot to search for synergistic effects [29].

Quantitative Data and Method Comparisons

Table 1: Comparison of Common Mutagenesis Techniques for Library Generation

| Technique | Purpose | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Typical Library Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis (SDM) | Introduce a specific pre-determined mutation. | High precision for single amino acid changes. | Does not generate diversity for screening. | N/A (single variant) |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis (SSM) | Explore all amino acid substitutions at a single residue. | Comprehensive analysis of a specific position's role. | Limited to one site; no exploration of epistasis. | ~20-100 variants per position [28] |

| Combinatorial Saturation Mutagenesis (CSM) | Explore all amino acid substitutions at multiple residues simultaneously. | Can find synergistic effects between mutations. | Library size explodes combinatorially (e.g., 2 residues = 400 variants; 5 residues = 3.2 million variants) [28]. | 10² - 10⸠variants [30] |

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) | Introduce random mutations across the entire gene. | No prior structural knowledge needed. | Biased mutation spectrum (e.g., favors transitions); most mutations are neutral or deleterious [1]. | 10ⴠ- 10ⶠvariants [1] |

Table 2: Comparison of Codon Schemes for Saturation Mutagenesis

| Codon Scheme | Codons Used | Amino Acids Encoded | Stop Codons? | Redundancy / Bias | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NNK | 32 codons | All 20 | Yes (1) | High bias; some AAs encoded by 6 codons, others by 1 [28]. | General use, especially with selection. |

| NNT | 32 codons | All 20 | Yes (1) | High bias; same as NNK [28]. | General use. |

| NDT | 12 codons | 12 (Phe, Leu, Ile, Val, Tyr, His, Asn, Asp, Cys, Arg, Ser, Gly) | No | Medium diversity; reduced set with good chemical diversity [29]. | Creating "smarter" focused libraries. |

| 22c-Trick | NDT, VHG, TGG (22 total) | All 20 | No | Low redundancy; only Val and Leu have 2 codons each [28]. | Creating high-quality, low-bias SSM/CSM libraries. |

| 20c-Tang Method | NDT, VMA, ATG, TGG (20 total) | All 20 | No | Minimal redundancy; one codon per amino acid [28]. | Creating the least redundant, unbiased libraries. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Site-Saturation Mutagenesis (SSM) Using Overlap Extension PCR

This is a standard method for creating a library of variants at a single amino acid position [30].

Materials:

- Template DNA: Plasmid containing the gene of interest.

- Primers: Forward and reverse mutagenic primers containing the degenerate codon (e.g., NNK or NDT) at the target position. Primers should be complementary, ~25-45 bases long, with the degenerate codon in the middle.

- High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase: To minimize introduction of secondary errors.

- DpnI Restriction Enzyme: To digest the methylated parent template.

- Competent E. coli cells.

Step-by-Step Method:

- PCR Amplification: Set up two separate PCR reactions.

- Reaction A: Uses a forward primer specific to your vector and the reverse mutagenic primer.

- Reaction B: Uses the forward mutagenic primer and a reverse primer specific to your vector.

- Purify PCR Products: Gel-purify the products from Reactions A and B to remove primers and non-specific products.

- Overlap Extension PCR: Combine the purified fragments from A and B. Perform a PCR reaction without any primers for ~10-15 cycles. The overlapping ends of the fragments will prime each other, resulting in a full-length gene containing the mutation.

- Amplify Full-Length Product: Add the external forward and reverse vector primers to the reaction and run for an additional ~20 cycles to amplify the now-assembled full-length plasmid.

- Digest Template: Treat the final PCR product with DpnI to digest the original methylated template DNA.

- Transform and Plate: Transform the resulting DNA into competent E. coli and plate on selective media to generate the library for screening [30].

Protocol 2: CASTing for a Two-Residue Hotspot

This protocol uses Golden Gate assembly to seamlessly combine saturation mutagenesis at two different sites [29].

Materials:

- Type IIS Restriction Enzymes: e.g., BsaI or SapI, which cut outside their recognition site, allowing for scarless assembly.

- T4 DNA Ligase: For ligation of the fragments.

- Gene Fragments: The gene is split into parts, with the target residues located in different parts. Each part is cloned into a vector with the appropriate Type IIS sites.

- Saturation Mutagenesis Libraries: Pre-created libraries for Part A (containing residue 1) and Part B (containing residue 2) using SSM (see Protocol 1).

Step-by-Step Method:

- Library Generation for Individual Parts: Perform SSM on Part A and Part B separately to create two focused libraries.

- Golden Gate Assembly:

- Set up a one-pot reaction containing:

- The library of mutated Part A

- The library of mutated Part B

- The recipient vector (containing the remaining parts of the gene)

- Type IIS restriction enzyme (e.g., BsaI)

- T4 DNA Ligase

- ATP

- Cycle the reaction between the restriction temperature and ligation temperature (e.g., 37°C and 16°C) for many cycles (~30-50).

- Set up a one-pot reaction containing:

- Assembly Principle: In each cycle, the enzyme cuts each fragment, releasing it with unique overhangs. The ligase then assembles them in the correct order. Because the recognition site is lost upon ligation, the reaction is driven to completion.

- Transform and Screen: Transform the final assembly reaction into E. coli. This creates a combinatorial library where mutations from Part A and Part B are randomly reassociated, allowing you to screen for synergistic effects [29].

Workflow and Strategy Diagrams

Diagram Title: SSM and CASTing Library Generation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Site-Directed and Saturation Mutagenesis

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies gene fragments with minimal error rates during PCR steps. | Essential for generating high-quality libraries without unwanted background mutations. Examples include Q5 (NEB) or PfuUltra (Agilent). |

| Unbiased Degenerate Primers | Encodes all (or a balanced set of) amino acids at the target codon during SM. | The choice of codon (NNK, NDT, 22c-trick) directly impacts library bias and must be selected based on experimental goals [28]. HPLC purification is recommended. |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes (e.g., BsaI, SapI) | Enables scarless, directional assembly of multiple DNA fragments. | The core enzyme for Golden Gate assembly strategies, allowing efficient combinatorial library construction from separate mutated gene parts [29]. |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Digests the methylated parent plasmid template after PCR. | Critical for reducing background and enriching for newly synthesized, mutated plasmids in many SDM and SSM protocols. |

| Golden Gate Assembly System | A pre-optimized system for modular cloning. | Streamlines the construction of complex libraries by combining a Type IIS enzyme and ligase in a single reaction buffer [29]. |

| Cloning Vector with Selection Marker | Carries the gene of interest and allows for selection in a host organism. | Vectors with a T5 or T7 promoter are common for expression in E. coli. An antibiotic resistance gene (e.g., ampicillin, kanamycin) is essential for selection. |

| Sulmazole | Sulmazole, CAS:73384-60-8, MF:C14H13N3O2S, MW:287.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| CRBN ligand-12 | CRBN ligand-12, MF:C15H16F2N2O3, MW:310.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the field of directed evolution, recombination techniques are powerful methods for mimicking natural sexual evolution in the laboratory. By shuffling genetic elements from multiple parent genes, researchers can create vast libraries of chimeric progeny sequences. This process allows for the block-wise exchange of beneficial mutations and the removal of deleterious ones, accelerating the evolution of proteins with enhanced properties such as stability, activity, and substrate specificity. For researchers engineering biosynthetic enzymes, these methods provide a critical tool for exploring functional sequence space more efficiently than methods relying solely on point mutations [31] [32].

This guide focuses on two key in vitro recombination methods: DNA shuffling and the Staggered Extension Process (StEP). The following sections provide detailed protocols, troubleshooting advice, and resource information to support your experimental work.

DNA Shuffling: Core Protocol & Methodology

DNA shuffling, also known as molecular breeding, is a method pioneered by Willem P.C. Stemmer in 1994. It involves the random fragmentation of parent genes followed by their reassembly into full-length, chimeric genes through a primerless PCR reaction [33] [34].

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Preparation of Linear Input DNA: Generate double-stranded DNA of your target gene(s). This can be achieved either by PCR amplification using gene-specific primers or by restriction digestion of parental plasmid DNA. Using a thermostable, proofreading DNA polymerase (e.g., Pfu or KOD) is recommended to minimize spurious point mutations. Purify the resulting linear DNA, typically 2 μg total, via agarose gel electrophoresis to eliminate residual primers, template, or protein [31].

Fragmentation via DNase I Digestion:

- Prepare a fresh 10X DNase I buffer (e.g., 500 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM MnCl2) [31].

- Combine 2 μg of purified linear DNA, 5 μl of 10X DNase I buffer, and water to a total volume of 50 μl.

- Equilibrate the mixture at 15°C for 5 minutes in a thermal cycler.

- Add 0.5 μl of DNase I (diluted to 1 U/μl in 1X buffer) and incubate at 15°C for 3 minutes.

- Stop the reaction by heating to 80°C for 10 minutes [31].

- Critical Note: Incubation time and enzyme concentration are crucial for controlling fragment size. Test aliquots with different incubation times (30 seconds to 12 minutes) to standardize your conditions. Fragments of 100-300 bp or 400-1000 bp are often ideal for efficient reassembly [31] [35] [1].

Purification of Fragments: Purify the digested DNA using a PCR clean-up kit. While not always essential, gel purification can be used to select a specific size range of fragments, which helps increase the diversity of the final library [31].

Reassembly by Primerless PCR:

- Set up a 100 μl reassembly reaction containing:

- 200 ng of purified DNA fragments

- 2 units of a blend of Family A and Family B DNA polymerases

- 10 μl of 600 mM Tris-SO4 (pH 8.9), 180 mM Ammonium Sulfate

- 5 μl of 4 mM dNTPs

- 4 μl of 50 mM MgSO4

- Water to volume [31].

- Run the following thermal cycling program ("progressive hybridization"):

- 94°C for 2 minutes

- 35 cycles of: [94°C for 30 seconds, then a series of annealing/extension steps from 65°C down to 41°C (e.g., 65°C for 90s, 62°C for 90s, 59°C for 90s, ...), finishing with 68°C for 90 seconds per kb of gene length]

- Final extension at 68°C for 2 minutes per kb [31].

- Set up a 100 μl reassembly reaction containing:

Reamplification of Shuffled Library:

- Use 5 μl of the purified reassembly product as template in a standard PCR.

- Use a proofreading DNA polymerase and a set of "inner" primers that bind to the ends of your gene of interest.

- 20 PCR cycles are typically sufficient [31].

- Gel-purify the final amplified library for downstream cloning, screening, or selection [31].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for DNA shuffling.

Staggered Extension Process (StEP): Core Protocol & Methodology

The Staggered Extension Process (StEP) is a simpler recombination technique that does not require a physical fragmentation step. Instead, recombination occurs during extremely short primer extension cycles in a single tube [32].

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Template Preparation: Prepare DNA templates containing the target sequences to be recombined. These can be plasmids, PCR products, or other DNA forms carrying your gene of interest [32].

StEP Reassembly Reaction:

- Set up a 50 μl reaction containing:

- 1-20 ng of total template DNA

- 30-50 pmol of each flanking primer

- 1X Taq buffer (e.g., 500 mM KCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3)

- 1.5 mM MgClâ‚‚

- 2 mM of each dNTP

- 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase [32].

- Run 80-100 cycles of the following two-step program:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 55°C for 5-15 seconds. This short extension time is critical. [32]

- Set up a 50 μl reaction containing:

Optional DpnI Digestion: If the parent templates were isolated from a dam methylation-positive E. coli strain, treat the StEP product with DpnI endonuclease for 1 hour at 37°C to digest the parental DNA and reduce background [32].

PCR Amplification (if needed):

- If a discrete full-length band is not obtained after the StEP reaction, use 1 μl of the StEP product as a template in a standard PCR.

- Use the same flanking primers and run 25 cycles with a full extension time (e.g., 60 seconds per kb) [32].

Cloning: Gel-purify the product, digest it with the appropriate restriction enzymes, and ligate it into your desired cloning vector [32].

The diagram below outlines the StEP recombination workflow.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low diversity in final library |

|

|

| No full-length product after reassembly |

|

|

| High background of non-recombined parent sequences |

|

|

| Excessive point mutations in final library |

|

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main advantages of DNA shuffling over random mutagenesis methods like error-prone PCR? DNA shuffling allows for the recombination of beneficial mutations from multiple parents in a single step and can effectively purge neutral and deleterious mutations. This enables a more efficient exploration of sequence space and can lead to faster functional improvements compared to the accumulation of solely point mutations [34] [32].

Q2: When should I choose StEP recombination over traditional DNA shuffling? StEP is technically simpler and less labor-intensive as it eliminates the DNase I fragmentation and purification steps, performing the entire process in a single tube. It is a good choice for rapid prototyping or when working with many different gene sets. However, controlling the crossover frequency can be more challenging than in DNA shuffling [32].