Comparative Substrate Specificity of Enzyme Homologs: Mechanisms, Methods, and Impact on Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the comparative substrate specificity of enzyme homologs, a critical factor in enzymology and pharmaceutical development.

Comparative Substrate Specificity of Enzyme Homologs: Mechanisms, Methods, and Impact on Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the comparative substrate specificity of enzyme homologs, a critical factor in enzymology and pharmaceutical development. We explore the foundational principles of enzyme-substrate interactions, including the lock-and-key and induced-fit models, and delve into the evolutionary mechanisms such as gene duplication and divergence that lead to functional diversity in enzyme families. The review covers advanced methodological approaches, including multiplexed assays and mass spectrometry, for accurately determining specificity constants in complex, multi-substrate environments. We also address common challenges in specificity profiling, such as enzyme promiscuity and stability-activity trade-offs, and present optimization strategies informed by recent studies on distal mutations. Finally, we discuss validation frameworks and the direct implications of specificity profiling for targeting enzymes in drug discovery, offering a synthesized perspective for researchers and scientists aiming to exploit enzymatic specificity for therapeutic innovation.

Unraveling the Principles: How Enzyme Homologs Achieve Substrate Specificity

Historical Foundations of Enzyme-Substrate Binding

The conceptual understanding of how enzymes recognize and bind their substrates has evolved significantly over the past century, driven by accumulating experimental evidence and technological advancements. The earliest model, proposed by Emil Fischer in 1894, introduced the lock-and-key analogy to explain enzyme specificity [1]. This model posited that the enzyme's active site and its substrate possess complementary, pre-formed shapes that fit together perfectly in a single step, much like a key fits into a specific lock. According to this framework, the enzyme's active site is a static, rigid structure that does not undergo conformational changes upon substrate binding [1] [2]. The binding was described as inflexible and very strong, with no development of a transition state before the reactants underwent chemical changes [1].

In contrast to this static view, the induced fit model, proposed by Daniel Koshland in 1958, presented a more dynamic interaction mechanism [1]. This model recognized that the active site of the enzyme often does not fit the substrate perfectly before binding [3]. Instead, the enzyme's active site is more flexible and undergoes a conformational change as the substrate binds, molding itself to fit the substrate more precisely [1] [3] [2]. This dynamic binding maximizes the enzyme's ability to catalyze its reaction by creating an ideal binding arrangement that stabilizes the transition state [3]. The induced fit model better accounts for the observed catalytic promiscuity of many enzymes and their ability to act on substrates beyond those for which they were originally evolved [4].

The evolution from the lock-and-key to the induced fit model represents a fundamental shift in understanding enzyme mechanics—from viewing enzymes as rigid structures to recognizing them as dynamic molecular machines with flexible active sites that optimize their configuration for substrate binding and catalysis. This conceptual framework provides the foundation for modern computational approaches to predicting and engineering enzyme specificity.

Contemporary Computational Models for Specificity Prediction

Recent advances in computational biology have produced sophisticated tools that build upon the foundational models of enzyme-substrate interactions. These tools employ machine learning and structural bioinformatics to predict substrate specificity with increasing accuracy, providing powerful resources for enzyme engineering and drug discovery. The table below compares three cutting-edge platforms for enzyme specificity prediction:

Table 1: Computational Tools for Predicting Enzyme Substrate Specificity

| Tool Name | Underlying Methodology | Key Innovations | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| EZSpecificity | Cross-attention SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network [4] [5] | Trained on comprehensive enzyme-substrate interactions; incorporates 3D structural data [4] | 91.7% accuracy for top pairing predictions with halogenases [4] [5] |

| EZSCAN | Logistic regression on homologous sequences [6] [7] | Machine learning classification of residue features; identifies specificity-determining residues [6] | Accurately predicted known specificity residues in trypsin/chymotrypsin, AC/GC, LDH/MDH pairs [7] |

| EnzyControl | Diffusion or flow matching with modular adapter (EnzyAdapter) [8] | Generates enzyme backbones conditioned on catalytic sites and substrates; two-stage training [8] | 13% improvement in designability and catalytic efficiency over baselines [8] |

These computational approaches differ significantly in their underlying principles and applications. EZSpecificity leverages three-dimensional structural information through graph neural networks that respect rotational and translational symmetry (SE(3)-equivariance), enabling it to capture intricate geometric relationships between enzymes and substrates [4]. In contrast, EZSCAN employs a sequence-based approach that identifies critical residues governing substrate specificity by analyzing patterns in homologous enzymes, framing the challenge as a binary classification problem [6] [7]. EnzyControl represents a more ambitious approach that actually generates novel enzyme backbones with specified substrate preferences, bridging rational design and de novo enzyme creation [8].

Each platform addresses distinct aspects of the substrate specificity prediction challenge. EZSpecificity excels at predicting interactions between known enzymes and substrates, while EZSCAN identifies the specific amino acid residues that determine specificity, providing insights for rational engineering. EnzyControl goes further by generating entirely new enzyme structures optimized for specific substrates, pushing the boundaries of computational enzyme design.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

EZSCAN's Sequence-Based Residue Identification

The EZSCAN methodology employs a systematic computational pipeline to identify amino acid residues critical for substrate specificity. The protocol begins with data acquisition of amino acid sequences from structurally homologous enzymes with differing substrate specificities [7]. These sequences undergo multiple sequence alignment to ensure proper positional correspondence [6] [7]. The aligned sequences are then converted into one-hot encoded vectors, where each residue position is represented numerically [7]. These encoded sequences serve as input features for a logistic regression classifier trained to distinguish between enzyme classes based on their substrate preferences [7]. The model identifies critical residues by analyzing the partial regression coefficients, with the magnitude of coefficients indicating the importance of specific amino acid types at particular positions for determining substrate specificity [7].

Validation of EZSCAN followed a rigorous experimental protocol. Researchers applied the method to three well-characterized enzyme pairs: trypsin/chymotrypsin, adenylyl cyclase/guanylyl cyclase (AC/GC), and lactate dehydrogenase/malate dehydrogenase (LDH/MDH) [6] [7]. For the LDH/MDH pair, they conducted experimental validation through site-directed mutagenesis of identified residues, followed by enzyme kinetics assays to measure catalytic efficiency with different substrates [7]. The results confirmed that mutations at predicted residues could alter substrate specificity while maintaining protein expression levels, successfully enabling LDH to utilize oxaloacetate [7].

Table 2: EZSCAN Validation on Enzyme Pairs

| Enzyme Pair | Key Specificity Residues Identified | Validation Approach | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin/Chymotrypsin | D189/S189 (ranked 4th); Y172/W172 (ranked 1st) [7] | Comparison with known literature | Confirmed known specificity-determining residues [7] |

| AC/GC | A946/V938; I1019/L1003; K938/E930 [7] | Computational validation | Recovered cofactor specificity patterns [7] |

| LDH/MDH | Q86; E90; I237; A223 [7] | Site-directed mutagenesis and kinetics | Switched substrate specificity; maintained expression [7] |

EZSpecificity's Structural Evaluation Protocol

The EZSpecificity framework employs a distinct methodology centered on three-dimensional structural information. The development team created a comprehensive database of enzyme-substrate interactions by combining existing experimental data with millions of docking simulations performed for different enzyme classes [4] [5]. These simulations provided atomic-level interaction data between enzymes and substrates, addressing the limitation of sparse experimental data [5]. The team then designed a cross-attention graph neural network architecture that processes both enzyme structures and substrate representations, allowing the model to learn complex interaction patterns [4].

For validation, the researchers employed a dual approach using both unknown substrate/enzyme databases and protein-family-specific testing [4]. The most compelling validation came from experimental testing on eight halogenase enzymes with 78 substrates—a class particularly relevant for pharmaceutical applications [4] [5]. The experimental protocol involved expressing the halogenases, incubating them with predicted substrates, and measuring product formation to determine reactive pairs [4]. EZSpecificity achieved remarkable 91.7% accuracy in identifying the single potential reactive substrate, significantly outperforming the state-of-the-art ESP model at 58.3% accuracy [4] [5].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between the historical models and modern computational approaches:

Performance Comparison Across Experimental Contexts

Rigorous benchmarking of computational tools is essential for assessing their practical utility in real-world research and development settings. The performance of specificity prediction platforms varies significantly across different enzyme classes and experimental scenarios, highlighting the importance of context-dependent tool selection.

Table 3: Comparative Performance Across Enzyme Classes and Applications

| Tool | Enzyme Class/Category | Performance Metric | Comparative Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| EZSpecificity | Halogenases [4] [5] | Accuracy for top pairing prediction | 91.7% vs. ESP's 58.3% [4] [5] |

| EZSCAN | LDH/MDH pair [7] | Success in altering substrate specificity | Enabled LDH to utilize oxaloacetate via mutations [7] |

| EnzyControl | Multiple enzyme families [8] | Designability and catalytic efficiency | 13% improvement over baseline models [8] |

| EZSpecificity | General enzyme classes [4] | Broad applicability | Outperformed existing models in four testing scenarios [4] |

The experimental data reveal distinctive strengths for each platform. EZSpecificity demonstrates exceptional performance in predicting reactive substrate pairs, particularly for enzyme classes like halogenases that are structurally characterized but poorly annotated in functional databases [4] [5]. Its graph neural network architecture appears particularly well-suited for capturing the complex three-dimensional relationships between enzyme active sites and potential substrates.

EZSCAN excels in identifying individual residues that govern substrate specificity, providing clear targets for rational engineering approaches [6] [7]. Its sequence-based methodology offers practical advantages when structural data are limited, and its successful application to diverse enzyme pairs (serine proteases, cyclases, and dehydrogenases) demonstrates broad applicability across different enzyme mechanistic classes [7].

EnzyControl represents a paradigm shift beyond prediction to actual generation of enzyme designs with desired substrate specificities [8]. Its performance in generating functional enzyme backbones with improved catalytic efficiency highlights the potential of generative artificial intelligence in enzyme engineering, though this approach may require more extensive experimental validation before widespread adoption [8].

The following workflow illustrates a typical experimental pipeline for developing and validating specificity prediction tools:

Successful investigation of enzyme substrate specificity requires both computational tools and experimental resources. The table below details key reagents and computational resources essential for research in this field:

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Substrate Specificity Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | EZSpecificity, EZSCAN, EnzyControl [6] [4] [8] | Prediction of enzyme-substrate interactions and specificity-determining residues |

| Enzyme-Substrate Datasets | EnzyBind (11,100 enzyme-substrate pairs) [8] | Training and benchmarking data for predictive models |

| Structural Biology Resources | PDBBind database, RDKit library [8] | Source of protein-ligand complexes and cheminformatics analysis |

| Validation Enzymes | Halogenases, LDH/MDH, trypsin/chymotrypsin [4] [7] | Experimental validation of specificity predictions |

| Sequence Analysis Tools | MAFFT software, multiple sequence alignment [8] | Identification of evolutionarily conserved functional motifs |

The EnzyBind dataset represents a particularly significant advancement, providing 11,100 experimentally validated enzyme-substrate pairs specifically curated from PDBbind with precise pocket structures and substrate conformations [8]. This addresses a critical limitation in earlier datasets that lacked precise pocket information or relied on synthetic data without experimental validation [8].

For researchers investigating specific enzyme mechanisms, halogenases have emerged as important model systems due to their pharmaceutical relevance and complex substrate specificity patterns [4]. The LDH/MDH enzyme pair continues to serve as a benchmark system for evaluating specificity prediction methods, as their structural homology contrasted with distinct substrate preferences provides an ideal test case for distinguishing functional from structural constraints [7].

Specialized substrates like 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose have gained importance for studying enzyme specificity in metabolic contexts, particularly in cancer metabolism and viral inhibition studies, where they serve as glycolytic inhibitors to probe substrate-enzyme interactions [9]. Similarly, hemopressin peptides are increasingly used in neuroscience research to study enzyme-substrate interactions involving cannabinoid receptors and their metabolic enzymes [9].

The evolution from simple lock-and-key analogies to sophisticated computational models reflects our deepening understanding of enzyme-substrate interactions. Contemporary tools like EZSpecificity, EZSCAN, and EnzyControl each offer distinct advantages for different research scenarios. EZSpecificity excels in predicting interactions for structurally characterized enzymes, making it ideal for enzyme selection in biocatalysis projects. EZSCAN provides unparalleled insights into the specific residues governing specificity, offering clear engineering targets for rational design approaches. EnzyControl represents the frontier of generative enzyme design, creating novel protein scaffolds optimized for specific substrates.

The choice among these tools depends fundamentally on the research objective: predicting interactions for known enzyme structures, identifying residues for engineering natural enzymes, or generating entirely new enzyme designs. As these computational approaches continue to evolve and integrate with experimental validation, they promise to accelerate both fundamental understanding of enzyme mechanism and practical applications in biotechnology, drug discovery, and sustainable chemistry.

The Role of Ligand-Driven Conformational Changes in Specificity

In enzymatic catalysis, substrate specificity—the precise recognition and selective transformation of particular substrates—is a fundamental property governing cellular function. A central, yet complex, mechanism underlying this specificity involves ligand-induced conformational changes, where the binding of a substrate or regulator actively reshapes the enzyme's three-dimensional structure [4]. This dynamic process transcends the static lock-and-key model, revealing that enzymes are molecular machines whose functional state is often achieved only upon interaction with their ligands. For enzyme homologs, subtle differences in how these conformational changes are orchestrated can dictate divergent biological roles and substrate profiles. Understanding these dynamics is therefore critical for elucidating reaction mechanisms, advancing protein engineering, and facilitating rational drug discovery [6]. This guide objectively compares the experimental strategies and technologies used to dissect these conformational dynamics, providing a framework for researchers aiming to study specificity within enzyme families.

Comparative Analysis of Research Methodologies

Research in this field relies on a suite of biophysical, computational, and structural techniques. The table below compares the primary methodologies used to detect and characterize ligand-induced conformational changes.

Table 1: Comparison of Methodologies for Studying Ligand-Driven Conformational Changes

| Methodology | Key Principle | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Applications in Specificity Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) [10] | Visualizes protein structures frozen in vitreous ice, capturing multiple conformational states. | Atomic (1.9 – 3.5 Å) | Static snapshots of different states | Mapping global conformational states in enzyme complexes (e.g., CODH-ACS); identifying open, closed, and intermediate structures. |

| Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) [11] | Measures deuterium incorporation into protein backbone, revealing solvent accessibility and hydrogen bonding dynamics. | Peptide-level (5-20 amino acids) | Seconds to hours | Profiling dynamic changes across the protein structure; comparing conformational impacts of different ligand modalities (agonists vs. antagonists). |

| Biosensor Platforms (SPR, SHG, SAW) [12] | Detects changes in mass, refractive index, or morphological state upon ligand binding in real-time. | Macromolecular (whole protein) | Milliseconds to minutes | Label-free detection of conformational transitions; distinguishing agonists from antagonists based on induced structural rearrangements. |

| Machine Learning (EZSpecificity) [4] | SE(3)-equivariant graph neural networks trained on enzyme-substrate structures to predict specificity. | Atomic and residue-level | Predictive (no temporal data) | In silico prediction of substrate specificity; identifying key residues governing functional differences in enzyme homologs. |

| X-ray Crystallography [12] | Provides a high-resolution static structure of the protein-ligand complex. | Atomic (~2 Ã…) | Static snapshot | Determining precise ligand-binding poses and active site geometry in specific conformational states. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Cryo-EM for Trapping Conformational Intermediates

The application of cryo-EM to the CO-dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase (CODH-ACS) complex from Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans provides a protocol for visualizing conformational states [10].

- 1. Sample Preparation and Trapping: The enzyme complex is purified under anaerobic conditions. Intermediate states of the catalytic cycle are trapped through substrate analog incubation or chemical quenching before rapid vitrification. For example, states are trapped by exposing the enzyme to carbon monoxide, methyl donors, or acetyl-CoA precursors.

- 2. Grid Preparation and Vitrification: A sample aliquot (3-4 µL) is applied to a cryo-EM grid, blotted to remove excess liquid, and plunged into a cryogen (ethane-propane mix) cooled by liquid nitrogen.

- 3. Data Collection and Processing: Micrographs are collected using a high-end cryo-electron microscope (e.g., Titan Krios). Hundreds to thousands of micrographs are processed through software pipelines involving particle picking, 2D classification, and 3D reconstruction to resolve structures at 1.9–2.5 Å resolution.

- 4. Conformational Analysis: Multiple 3D reconstructions are analyzed and classified to identify distinct conformational states (e.g., "wobbly," "half-closed," "closed"). The structural differences, particularly in flexible domains and active site access channels, are quantified.

HDX-MS for Mapping Dynamic Changes

The study of the turkey β1-adrenergic receptor (tβ1AR) exemplifies the use of HDX-MS to map ligand-specific dynamics [11].

- 1. Sample Preparation: The purified GPCR is reconstituted into a suitable membrane mimetic, such as lipid nanodiscs or detergent micelles (e.g., with 0.1% DDM).

- 2. Ligand Binding and Deuterium Labeling: The receptor is incubated with an excess of ligand (agonist, antagonist, or partial agonist) to achieve >98% binding occupancy. The labeling reaction is initiated by diluting the protein-ligand complex into deuterated buffer for defined time periods (e.g., 15 seconds, 2 minutes, 30 minutes, 120 minutes).

- 3. Quenching and Digestion: The reaction is quenched by lowering the pH and temperature (to pH 2.5 and 0°C). The quenched sample is passed over an immobilized protease column (e.g., pepsin, or a dual protease column of pepsin and type XIII) for rapid digestion.

- 4. LC-MS Analysis and Data Processing: The resulting peptides are separated by liquid chromatography and analyzed by mass spectrometry to measure mass increases due to deuterium uptake. Software is used to identify peptides and calculate deuterium incorporation levels. Differential HDX is calculated by comparing the deuterium uptake of the ligand-bound state against the apo receptor.

Figure 1: HDX-MS Experimental Workflow. The workflow shows the key steps from protein-ligand incubation to the generation of a differential deuterium uptake map, highlighting regions stabilized or destabilized by ligand binding [11].

Biosensor Analysis for Real-Time Detection

Biosensors offer a label-free method to detect binding and subsequent conformational changes [12].

- 1. Surface Immobilization: The protein (e.g., AChBP) is immobilized onto a biosensor chip surface (e.g., CMS chip for SPR) via standard amine-coupling chemistry. A reference surface is prepared without protein.

- 2. Ligand Injection and Data Acquisition: Ligands are injected over the protein and reference surfaces at a range of concentrations in a running buffer. Sensorgram data (response units vs. time) is collected for both the association and dissociation phases.

- 3. Data Interpretation: Sensorgrams are qualitatively analyzed. Simple, single-exponential curves suggest a 1:1 binding model. Complex sensorgrams with distortions, negative slopes, or signals dropping below baseline indicate secondary events, interpreted as ligand-induced conformational changes (e.g., compaction or expansion of the protein structure).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful experimentation in this field depends on specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions used in the cited research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Conformational Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| AChBPs (Ls-AChBP, Ac-AChBP) [12] | Soluble homologs of Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channels; model proteins that undergo nAChR-like conformational changes. | Used in biosensor and crystallography studies as a surrogate for membrane-bound neurotransmitter receptors. |

| Nanodiscs / Membrane Mimetics [11] | Lipid bilayers stabilized by membrane scaffold proteins (MSPs); provide a native-like environment for membrane proteins. | Reconstitution of GPCRs like tβ1AR for HDX-MS studies to maintain stability and functionality. |

| Immobilized Protease Columns [11] | Micro-reactors filled with agarose-immobilized pepsin or other non-specific proteases for rapid, efficient digestion. | Used in the HDX-MS workflow to digest the quenched protein sample into peptides for mass spectrometry analysis. |

| Ti(III)-EDTA / Dithionite [10] | Strong chemical reductants used to manipulate the oxidation state of metalloenzyme clusters. | Studying the effect of reduction on the conformational equilibrium of the CODH-ACS complex. |

| High-Throughput Peptide Arrays [13] | Cellulose-membrane or glass-slide bound peptide libraries representing protein segments or sequence permutations. | Profiling enzyme substrate specificity and generating training data for machine learning models (e.g., for SET8 methyltransferase). |

| 7,7-Dimethyloxepan-2-one | 7,7-Dimethyloxepan-2-one||RUO | 7,7-Dimethyloxepan-2-one is a lactone monomer for polymer research. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for personal use. |

| 1-Pentadecyne, 1-iodo- | 1-Pentadecyne, 1-iodo-|CAS 78076-36-5 | 1-Pentadecyne, 1-iodo- (CAS 78076-36-5) is a terminal alkyne for synthetic chemistry research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or therapeutic use. |

Integrating Computational and Experimental Data

Machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing the prediction of enzyme specificity by learning the structural and sequence determinants of substrate selection. The EZSpecificity model exemplifies this approach [4]. It uses a cross-attention-empowered, SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network architecture. This allows it to directly learn from the 3D atomic coordinates of enzyme structures and their associated substrates, enabling accurate predictions of which substrates an enzyme will act upon. In experimental validation with eight halogenases and 78 substrates, EZSpecificity achieved a 91.7% accuracy in identifying the single potential reactive substrate, a significant improvement over a state-of-the-art model that achieved only 58.3% accuracy [4].

A complementary "ML-hybrid" approach was successfully applied to predict substrates for PTM-inducing enzymes like the methyltransferase SET8 and deacetylases SIRT1-7 [13]. This method combines high-throughput in vitro peptide array experiments, which provide enzyme-specific training data, with machine learning models. This ensemble method demonstrated a significant performance increase, correctly predicting 37-43% of proposed PTM sites, and unveiled previously unreported pathways for SIRT family enzymes [13].

Figure 2: Integrating Machine Learning with Experiments. The diagram shows the synergistic cycle where experimental data trains ML models, which make predictions that are then validated experimentally, leading to new functional insights [6] [4] [13].

The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores that there is no single superior technique for studying ligand-driven conformational changes. Instead, the power lies in a complementary, multi-method approach. Cryo-EM provides unparalleled visual snapshots of distinct conformational states, HDX-MS offers a peptide-level map of dynamic flexibility, and biosensors deliver real-time kinetic data on structural transitions. The emerging integration of these experimental data with sophisticated machine learning models, such as EZSpecificity and ML-hybrid approaches, marks a transformative advance. This synergy between empirical observation and computational prediction is rapidly accelerating our ability to decipher the molecular logic of enzyme specificity, with profound implications for designing novel therapeutics and engineered biocatalysts.

The Innovation-Amplification-Divergence (IAD) model provides a fundamental framework for understanding how gene duplication enables functional evolution. This model proposes that new genes evolve through a three-step process: first, a pre-existing parental gene acquires a novel, low-level activity (innovation); second, the gene undergoes duplication and amplification to a high copy number (amplification); and finally, the amplified gene copies accumulate mutations that lead to enzymatic specialization (divergence) [14]. This process allows functionally distinct new genes to evolve under continuous selection pressure, with selection maintaining the initial amplification and beneficial mutant alleles while relaxing for less improved gene copies [14].

In the context of comparative substrate specificity research, the IAD model offers critical insights into how enzyme homologs develop distinct functional profiles. This guide examines the IAD model alongside alternative evolutionary pathways, focusing on their roles in shaping enzyme substrate specificity—a key consideration for drug development targeting specific enzymatic functions. We present experimental data and methodologies that enable researchers to trace these evolutionary pathways and manipulate substrate specificity for biomedical applications.

Theoretical Framework: Evolutionary Pathways to Novel Enzyme Functions

The Innovation-Amplification-Divergence Model

The IAD model demonstrates remarkable efficacy in real-time evolutionary studies. In one foundational experiment with Salmonella enterica, researchers observed the complete IAD process occurring in fewer than 3,000 generations [14]. The parental gene possessed low levels of two distinct activities before duplication. Following amplification, different gene copies accumulated mutations that provided enzymatic specialization of different copies, resulting in improved fitness. This rapid evolutionary process underscores how gene duplication events serve as crucial catalysts for functional diversification in enzymes.

Alternative Evolutionary Pathways

While the IAD model represents one important pathway, enzyme evolution proceeds through multiple mechanisms:

Gene Loss-Driven Evolution: In bacterial systems, gene loss can drive functional adaptation of retained enzymes. Studies of Actinomycetaceae genomes reveal that loss of biosynthetic pathways leads to functional changes in retained bifunctional enzymes like PriA, which adapts from bifunctionality to monofunctionality through mutations in structurally mapped residues [15].

Structural Evolution Driven by Metabolic Constraints: Recent large-scale structural analyses of yeast enzymes across 400 million years reveal that metabolic network architecture imposes hierarchical constraints on enzyme evolution. Enzymes in essential core pathways (e.g., purine biosynthesis) show high structural conservation, while those in peripheral pathways exhibit greater structural diversity [16] [17].

Neofunctionalization from Preexisting Enzymes: Plant evolution studies demonstrate how entirely new enzymatic functions can emerge through gradual modification of existing enzymes. Canadian moonseed evolved a rare chlorination ability through stepwise modification of flavonol synthase (FLS) via gene duplications, losses, and mutations over hundreds of millions of years [18].

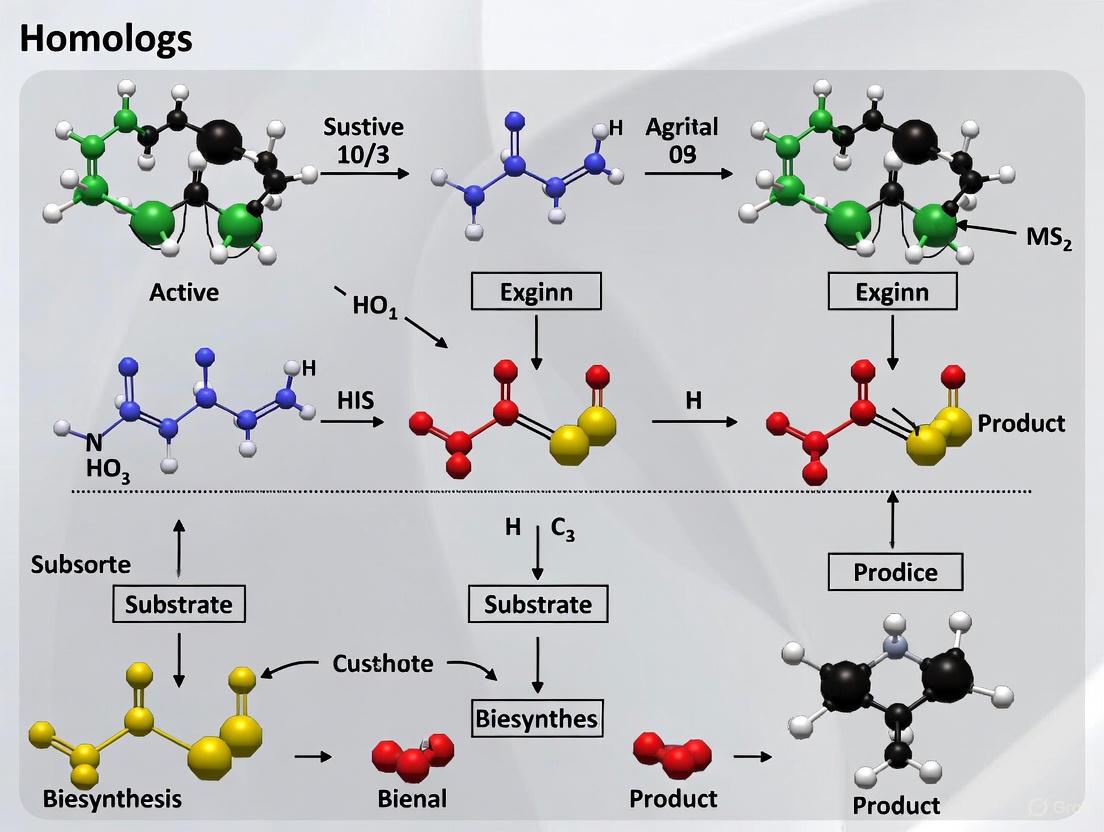

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in the IAD model compared to other evolutionary pathways:

Diagram Title: Evolutionary Pathways for Enzyme Specialization

Experimental Evidence: Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary Models

Direct Observation of IAD in Real-Time Evolution

The IAD model has been validated through direct experimental observation in bacterial systems. The key strength of this approach lies in its ability to track evolutionary trajectories under controlled laboratory conditions, providing quantitative data on the emergence of novel enzyme functions.

Table 1: Experimental Evidence for IAD Model in Bacterial Systems

| Experimental System | Parental Gene Function | Novel Function Emerged | Timeframe | Key Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella enterica model [14] | Preexisting parental gene with low levels of two activities | Specialized enzymatic activities in different copies | <3,000 generations | Gene copy number, growth rates, enzyme kinetics |

| Actinomycetaceae PriA evolution [15] | Bifunctional HisA/TrpF activity | Monofunctional specialized forms | Natural evolution across species | Enzyme kinetics, substrate specificity, phylogenetic analysis |

The experimental protocol for demonstrating IAD typically involves:

- Identifying a promiscuous parental enzyme with detectable low-level side activity

- Applying selective pressure that favors the novel activity

- Monitoring gene amplification events through PCR and sequencing techniques

- Tracking functional divergence through enzyme assays and kinetic measurements

- Sequencing evolved variants to identify mutations leading to specialization

Gene Loss-Driven Divergence in Natural Systems

In contrast to the IAD model, gene loss provides an alternative pathway for enzyme specialization. The study of PriA enzyme in Actinomycetaceae illustrates this principle beautifully [15]. Researchers combined phylogenomics and metabolic modeling to detect bacterial species evolving through gene loss, particularly in L-histidine and L-tryptophan biosynthesis pathways.

Experimental Protocol for Gene Loss Studies:

- Comparative genomics: Sequence multiple related genomes to identify patterns of gene loss

- Metabolic modeling: Predict which pathways become non-functional due to gene loss

- Phylogenetic analysis: Reconstruct evolutionary relationships between species

- Enzyme characterization: Express and purify homologous enzymes from different species

- Functional assays: Measure kinetic parameters and substrate specificity

- Structural analysis: Determine X-ray structures and map functional residues

This approach revealed how PriA enzymes adapted from bifunctionality in large genomes to monofunctional forms in reduced genomes, with mutations occurring primarily in residues subject to relaxed purifying selection [15].

Computational Prediction of Substrate Specificity Determinants

Modern bioinformatics approaches enable researchers to identify residues critical for substrate specificity, providing insights into evolutionary divergence. The EZSCAN (Enzyme Substrate-specificity and Conservation Analysis Navigator) method frames sequence comparison as a classification problem, treating each residue as a feature to identify key residues responsible for functional differences [6].

Table 2: Experimental Validation of Specificity-Determining Residues

| Enzyme Pair | Known Specificity Determinants | Computationally Predicted | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin/Chymotrypsin | S189, G216, G226 | Correctly identified | N/A (literature confirmation) |

| LDH/MDH | Multiple active site residues | Key specificity residues | Successful specificity switching via mutation |

| Adenylyl cyclase/Guanylyl cyclase | Substrate-binding residues | Accuracy confirmed | Method validation |

The experimental workflow for computational predictions involves:

- Multiple sequence alignment of homologous enzymes with different specificities

- Feature selection treating each residue position as a classification feature

- Machine learning classification to identify residues distinguishing specificities

- Site-directed mutagenesis to test predicted residues

- Enzyme kinetics to measure changes in substrate specificity

- Structural analysis to confirm mechanistic basis for specificity changes

Structural Insights into Enzyme Evolution

Large-Scale Structural Analysis of Enzyme Evolution

Recent advances in protein structure prediction, particularly through AlphaFold2, have revolutionized our ability to study enzyme evolution structurally. A landmark study analyzing 11,269 enzyme structures across 400 million years of yeast evolution revealed hierarchical patterns of structural evolution [16] [17] [19].

The methodology for this large-scale analysis included:

- Structure prediction and determination: 11,269 AlphaFold2-predicted and experimentally determined enzyme structures

- Orthogroup assignment: 424 orthologue groups associated with 361 metabolic reactions

- Structural alignment: Pairwise alignments to reference structures using matchmaker algorithm

- Quantitative metrics: Mapping Ratio (MR) and Conservation Ratio (CR) to quantify structural changes

- Metabolic integration: Linking structural data with metabolic network reconstructions and phenotypic data

This analysis revealed that enzyme evolution follows hierarchical constraints: species-level metabolic specialization impacts structural divergence, with enzymes in central carbon metabolism showing significant structural differences between fermentative and non-fermentative yeasts [17]. Furthermore, an enzyme's position in the metabolic network dictates evolutionary freedom, with essential core pathway enzymes showing high conservation compared to peripheral pathway enzymes [17].

Domain Acquisition and Functional Specialization

The comparison of two highly homologous chondroitinase ABC-type I enzymes (IM3796 and IM1634) demonstrates how domain acquisition drives functional diversification [20]. Despite 90.1% sequence identity, these enzymes show dramatically different substrate specificity and degradation patterns, primarily due to an extra N-terminal domain (Met1-His109) in IM1634.

The experimental approach for domain-function analysis:

- Sequence analysis: Identify homologous enzymes with divergent functions

- Structure modeling: Predict and compare tertiary structures

- Domain swapping: Delete domains from one enzyme and graft onto another

- Enzyme characterization: Measure activity, specificity, and degradation products

- Functional comparison: Corporate structural features with enzymatic properties

In the chondroitinase example, deletion of the N-terminal domain from IM1634 caused its enzymatic properties to resemble IM3796, while grafting this domain to IM3796 increased its similarity to IM1634 [20]. This demonstrates how domain acquisition represents an important mechanism in the divergence phase of the IAD model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Evolutionary Enzyme Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 [16] [17] | Protein structure prediction | Large-scale evolutionary analysis of enzyme structures |

| EZSCAN [6] | Identification of substrate specificity residues | Comparing enzyme homologs to identify key functional residues |

| Site-directed mutagenesis kits | Testing functional hypotheses | Validating predicted specificity-determining residues |

| Metabolic modeling software | Predicting pathway completeness and enzyme essentiality | Identifying genomes undergoing gene loss [15] |

| Droplet-based microfluidics [21] | Ultrahigh-throughput screening of enzyme variants | Directed evolution of enzymes with novel functions |

| Protein language models [22] | AI-driven protein design and fitness prediction | Generating novel enzyme sequences with desired functions |

| N-Undecylactinomycin D | N-Undecylactinomycin D, CAS:78542-40-2, MF:C73H108N12O16, MW:1409.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Anthracene, 2-ethynyl- | Anthracene, 2-ethynyl-, CAS:78053-56-2, MF:C16H10, MW:202.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Understanding evolutionary pathways of enzyme divergence has profound implications for pharmaceutical research. The IAD model provides a framework for explaining how enzyme families with diverse substrate specificities emerge in nature—knowledge that can be harnessed for drug development targeting specific enzyme isoforms. Similarly, gene loss-driven specialization reveals how environmental adaptations shape enzyme functions, offering insights for antimicrobial strategies against pathogenic bacteria [15].

The experimental protocols and computational methods summarized in this guide represent the cutting edge of enzyme evolution research. As structural prediction capabilities advance and high-throughput screening methods become more sophisticated, researchers are increasingly able to reconstruct evolutionary pathways and engineer enzymes with novel substrate specificities for therapeutic applications [22] [21]. These approaches continue to bridge evolutionary biology with drug discovery, enabling more precise targeting of enzymatic functions in disease treatment.

Enzyme Promiscuity as a Springboard for Evolving New Specificities

Enzyme specificity, the precise recognition of substrates by enzymes, has long been a foundational concept in biochemistry and catalytic machinery. However, the parallel phenomenon of enzyme promiscuity—where enzymes catalyze secondary reactions or act on non-native substrates—has emerged as a critical evolutionary springboard for developing new catalytic functions [23]. This inherent flexibility in enzyme function represents a fundamental resource in protein engineering, enabling researchers to bridge the gap between natural enzyme capabilities and industrial or therapeutic demands.

The comparative analysis of enzyme homologs reveals that catalytic promiscuity is not merely an experimental artifact but a widespread natural phenomenon with profound implications for enzyme evolution and engineering [23]. Current research leverages this promiscuity through sophisticated computational and directed evolution approaches, accelerating the creation of novel biocatalysts with tailored specificities for applications ranging from pharmaceutical synthesis to sustainable biomanufacturing.

Theoretical Foundation: Mechanisms and Classification of Enzyme Promiscuity

Defining Enzyme Promiscuity

Enzyme promiscuity generally manifests in three primary forms, each with distinct mechanistic bases and experimental implications [23]:

- Catalytic Promiscuity: The ability of an enzyme to catalyze multiple chemically distinct reactions through different catalytic mechanisms. This form often involves significant active site rearrangements or alternative transition state stabilizations.

- Substrate Promiscuity: Occurs when an enzyme catalyzes the same core reaction across different substrates. Methane monooxygenase exemplifies this category with its capacity to hydroxylate over 150 distinct substrates [23].

- Conditional Promiscuity: Enzymatic activities that emerge under non-physiological conditions, such as in organic solvents, extreme temperatures, or unusual pH values. Lipases, for instance, maintain functionality in both aqueous solutions and organic solvents [23].

Evolutionary Context of Promiscuous Activities

The YÄas-Jensen theory posits that ancestral enzymes at key evolutionary nodes possessed dual catalytic functions, with modern specialized enzymes evolving from these multifunctional ancestors [23]. This evolutionary trajectory suggests that contemporary enzymes retain latent promiscuous activities that can be reactivated under appropriate selective pressures. These residual activities provide a valuable foundation for engineering new enzymatic functions, particularly for reactions lacking natural enzyme templates.

Computational Approaches for Predicting and Engineering Specificity

Machine Learning-Driven Specificity Prediction

Recent advances in machine learning have revolutionized our capacity to predict and engineer enzyme substrate specificity. The EZSpecificity model, a cross-attention-empowered SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network, represents a breakthrough in accurately predicting enzyme-substrate interactions [4]. Trained on a comprehensive database of enzyme-substrate relationships, this architecture demonstrates remarkable predictive accuracy, achieving 91.7% accuracy in identifying single potential reactive substrates—significantly outperforming previous models (58.3% accuracy) [4].

The power of such models lies in their ability to integrate structural information with evolutionary data, creating predictive frameworks that account for the complex physical and chemical determinants of specificity. These computational tools enable researchers to navigate the vast sequence-function space of enzymes more efficiently, prioritizing variants with desired specificity profiles for experimental validation.

AI-Enhanced Enzyme Design Platforms

Integrated computational workflows now enable the in silico design of novel enzymes with customized specificities. These platforms employ machine learning algorithms to predict highly active enzyme variants from simulated mutant DNA sequences, dramatically accelerating the design-build-test cycle [24]. One such implementation demonstrated the capability to improve production of a small molecule drug from 10% to 90% yield while simultaneously designing specialized enzymes for eight additional therapeutic compounds [24].

These approaches leverage directed evolution principles while overcoming traditional bottlenecks through computational prediction, enabling rapid exploration of sequence spaces that would be prohibitive with conventional laboratory methods. The integration of artificial intelligence with high-throughput experimental validation represents a paradigm shift in enzyme engineering, compressing development timelines from months to days [24].

Structure Prediction Tools

Accurate protein structure prediction is fundamental to understanding and engineering enzyme specificity. AlphaFold has emerged as a transformative tool in this domain, enabling researchers to obtain high-confidence structural models without the time and resource investments of traditional methods like X-ray crystallography [25]. These predictions provide critical insights into active site architecture, substrate binding pockets, and potential catalytic residues—all essential for rational design of altered specificities.

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Structure Determination Methods

| Characteristic | AlphaFold | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Cost | Hours | Weeks to Months | Months |

| Sample Requirements | None | High-purity crystals | High-concentration samples |

| Cost Investment | Computational resources | Experimental equipment + supplies | High-end equipment |

| Suitable For | Monomers/multimers/complexes | Smaller proteins | Large complexes |

| Automation Level | High | Low | Medium |

Experimental Methodologies for Characterizing and Engineering Promiscuity

Directed Evolution and Rational Design

The engineering of promiscuous enzymes into specialized catalysts primarily employs two complementary approaches: directed evolution and rational design. Directed evolution mimics natural selection through iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening, progressively enhancing desired activities without requiring comprehensive mechanistic understanding [23]. Rational design, conversely, employs structural knowledge and computational modeling to make targeted modifications to enzyme active sites, often focusing on stabilizing transition states or altering substrate access [26].

These strategies frequently converge in semi-rational approaches that combine structural insights with combinatorial diversity. For instance, site-saturation mutagenesis targets specific residues while allowing combinatorial exploration of amino acid substitutions, efficiently balancing exploration and optimization in the sequence space.

CRISPR-Enabled Genome-Scale Screening

CRISPR-based technologies have unlocked powerful new approaches for functional genomics and enzyme discovery. The development of genome-scale multi-target CRISPR libraries enables systematic investigation of gene families with functional redundancy, overcoming a significant limitation in characterizing enzyme specificity [27]. In one implementation in tomato, researchers created a library containing 15,804 independent sgRNAs targeting 10,036 genes, organized into ten specialized sub-libraries focused on specific protein families like transporters, transcription factors, and enzymes [27].

This approach facilitated the identification of mutants with significant phenotypic variations in traits including fruit morphology, flavor compound synthesis, pathogen response, and nutrient absorption. The methodology demonstrates how systematic genetic perturbation can reveal novel enzyme functions and specificities at an unprecedented scale.

High-Throughput Screening in Enzyme Engineering

Advanced screening methodologies are essential for evaluating the functional outcomes of engineered enzyme variants. Droplet-based microfluidics has emerged as a particularly powerful platform, enabling ultra-high-throughput screening of enzyme libraries. In one application, researchers developed a novel bacteria-based biosensor for diacetylchitobiose deacetylase activity, allowing sorting of active enzyme variants at remarkable speeds [28].

These screening platforms typically incorporate the following key steps:

- Library generation through mutagenesis or DNA synthesis

- Compartmentalization of individual variants in water-in-oil emulsion droplets

- Fluorescent signal generation coupled to enzymatic activity

- Flow cytometry-based sorting of active variants

- Recovery and sequencing of enriched variants for iterative rounds of engineering

Case Studies in Specificity Engineering

Engineering Viral Protease Specificity for Antiviral Therapeutics

The SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease (3CLpro) represents a compelling case study in enzyme specificity and its therapeutic implications. Structural analyses reveal that 3CLpro maintains strict substrate specificity at the P1 position (preferring glutamine) and P2 position (favoring hydrophobic residues like leucine), while showing more flexibility at P1', P4, and P3 positions [29]. This specificity profile informed the design of protease inhibitors like nirmatrelvir and ensitrelvir, which incorporate complementary moieties that engage these specificity determinants while adding reactive warheads (e.g., aldehydes, α-ketoamides) for covalent inhibition [29].

The development journey from initial specificity characterization to approved therapeutics exemplifies how understanding enzyme specificity enables rational drug design. Structural biology provided critical insights into the conserved active site architecture across coronavirus 3CLproteases, facilitating the creation of broad-spectrum inhibitors with clinical utility against current and potentially emerging viral threats [29].

Exploiting Natural Promiscuity in Lanthipeptide Biosynthetic Enzymes

Lanthipeptide biosynthetic enzymes demonstrate remarkable natural promiscuity that researchers have harnessed to create diverse bioactive peptides. These enzymes, particularly those involved in post-translational modifications like dehydration and cyclization, exhibit exceptional substrate tolerance, enabling modification of non-cognate precursor peptides [30]. This flexibility has been leveraged to create lanthipeptide libraries with novel biological activities, including enhanced antimicrobial properties against multidrug-resistant pathogens.

For example, the promiscuous enzyme ProcM has been utilized to generate a library of 106 distinct lanthipeptides using identical leader peptide sequences, facilitating the discovery of novel inhibitors targeting the HIV p6 protein [30]. Similarly, the nisin biosynthetic machinery has been employed to install lanthionine rings on medically important peptides including angiotensin and erythropoietin, improving their stability and therapeutic potential [30].

Table 2: Representative Examples of Engineered Enzyme Specificities

| Enzyme/System | Native Specificity | Engineered Specificity | Engineering Approach | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytochrome P450 | Monooxygenation | C-H amination, other non-natural reactions | Directed evolution, rational design | Pharmaceutical synthesis |

| Lanthipeptide Biosynthetic Enzymes | Cognate precursor peptides | Diverse non-cognate substrates | Exploitation of natural promiscuity | Antimicrobial peptide development |

| SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro inhibitors | Viral polyprotein cleavage sites | Small molecule inhibitors | Structure-based drug design | Antiviral therapeutics |

| Halogenases | Limited native substrates | Expanded substrate range | Machine learning prediction | Synthesis of halogenated compounds |

Metabolic Engineering through Pathway-Wide Specificity Optimization

In metabolic engineering, simultaneous optimization of multiple enzyme specificities enables redirecting metabolic flux toward desired compounds. Researchers have developed CRISPR-dCas12a-mediated genetic circuit cascades that implement sophisticated control over biosynthetic pathways in Bacillus subtilis [28]. This system allows multiplexed regulation of gene expression, dynamically adjusting enzyme levels to balance pathway flux and minimize metabolic burden.

Similarly, the engineering of phosphatase substrate preference using a "Design–Build–Test–Learn" framework demonstrates how systematic specificity optimization can enhance bioproduction efficiency [28]. By iteratively refining enzyme specificities while monitoring system-level performance, researchers achieved significant improvements in product titers, showcasing the importance of considering enzyme specificity within its metabolic context.

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

The experimental approaches discussed require specialized reagents and methodologies. The following toolkit represents essential resources for research in enzyme specificity and promiscuity engineering.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Specificity Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-target CRISPR Libraries | Genome-scale screening of gene families | Identification of functionally redundant enzymes; discovery of new enzyme-substrate relationships [27] |

| AlphaFold Structure Predictions | Computational protein structure modeling | Active site analysis; substrate docking studies; rational design of specificity mutations [25] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Delivery of genome editing components | In vivo delivery of CRISPR systems for functional genomics [31] |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems | In vitro transcription and translation | Rapid testing of enzyme variants without cellular context limitations [24] |

| Directed Evolution Platforms | Iterative mutagenesis and screening | Optimization of enzyme specificity and activity [23] |

| Biosensors | Reporting on enzyme activity or metabolite production | High-throughput screening of enzyme libraries [28] |

Visualization of Key Concepts and Workflows

Enzyme Engineering Workflow Integrating Computational and Experimental Approaches

Enzyme Specificity Landscape and Engineering Strategies

The strategic exploitation of enzyme promiscuity has fundamentally transformed our approach to developing novel biocatalysts with customized specificities. By leveraging sophisticated computational tools, high-throughput screening methodologies, and deep mechanistic understanding, researchers can now navigate the vast landscape of possible enzyme functions with unprecedented precision and efficiency.

Future advances will likely emerge from several promising directions. The integration of artificial intelligence with automated experimental workflows will further compress design-build-test cycles, while single-cell multi-omics technologies will provide deeper insights into enzyme function within biological contexts [28] [24]. Additionally, the exploration of underexamined enzyme families and metagenomic sequences continues to reveal novel catalytic activities with potential biotechnological applications.

As these technologies mature, the systematic engineering of enzyme specificity will play an increasingly central role in addressing global challenges across medicine, manufacturing, and environmental sustainability. The continued refinement of comparative approaches for analyzing enzyme homologs will further illuminate the evolutionary principles governing enzyme function, providing foundational knowledge to guide future engineering efforts.

Analysis of Key Enzyme Superfamilies with Diverse Substrate Profiles

Enzyme superfamilies, groups of proteins descended from a common ancestor that often retain conserved structural features and catalytic mechanisms, are a fundamental source of functional diversity in biology. A key feature of many superfamilies is their divergent substrate specificity—the ability of individual homologs to recognize and catalyze reactions on distinct molecular substrates. Understanding the principles governing this specificity is critical for fields ranging from fundamental enzymology to industrial biocatalysis and drug discovery. This guide provides a comparative analysis of contemporary computational and experimental methodologies used to dissect substrate profiles within enzyme superfamilies, focusing on serine proteases, α-ketoglutarate-dependent non-heme iron (α-KG/Fe(II)) enzymes, and HAD superfamily phosphatases.

Comparative Analysis of Specificity Prediction Methodologies

Recent advances have produced powerful tools for predicting enzyme-substrate interactions. The table below compares three modern approaches, highlighting their core methodologies, performance, and optimal use cases.

Table 1: Comparison of Modern Enzyme Substrate Specificity Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Underlying Methodology | Key Superfamily Applications | Reported Performance | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZSpecificity [4] | Cross-attention SE(3)-equivariant Graph Neural Network | Halogenases; General enzyme-substrate pairs | 91.7% accuracy (vs. 58.3% for a state-of-the-art model) in identifying single reactive substrate from 78 candidates for halogenases [4]. | High accuracy; Incorporates 3D structural information of the active site; Generalizable model. | Requires enzyme structural data. |

| CATNIP [32] | Machine learning trained on High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) data | α-KG/Fe(II)-dependent enzymes | Successfully predicted compatible enzyme-substrate pairs for over 200 new biocatalytic reactions within the superfamily [32]. | Derisks synthetic biology; Built on validated experimental data; User-friendly web toolkit. | Currently specialized for α-KG/Fe(II) enzyme class. |

| EZSCAN [7] | Supervised machine learning (Logistic Regression) on sequence alignments | Serine Proteases (Trypsin/Chymotrypsin); Lactate/Malate Dehydrogenase (LDH/MDH) | Accurately predicted known specificity-determining residues (e.g., D189 in trypsin) and enabled experimental switching of LDH to MDH substrate preference [7]. | Pinpoints key residues; Only requires sequence information; Provides mechanistic insight. | Focuses on residue identification, not full substrate prediction. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Profiling Substrate Specificity

High-Throughput Experimentation for Reaction Discovery

The development of CATNIP for α-KG/Fe(II)-dependent enzymes provides a robust protocol for large-scale profiling of enzyme superfamilies [32].

- Library Design and Cloning: A diverse library of 314 α-KG/Fe(II)-dependent enzyme sequences was designed. Sequences were selected from a network of 265,632 unique sequences using a Sequence Similarity Network (SSN) to ensure coverage of distinct phylogenetic clusters and functional diversity. DNA for these sequences was synthesized and cloned into a pET-28b(+) expression vector.

- Protein Expression and Lysate Preparation: E. coli cells were transformed with the individual expression plasmids. Protein overexpression was carried out in a 96-deep-well plate format. Crude cell lysates were prepared and analyzed via SDS-PAGE to confirm protein expression; 78% of the library members showed clear expression.

- Biocatalytic Reaction Screening: Each enzyme lysate was tested against a diverse panel of potential substrate molecules under standard reaction conditions for the enzyme family (e.g., containing α-ketoglutarate and Fe(II)). Reactions were performed in a high-throughput microtiter plate format.

- Product Detection and Analysis: Reaction outcomes were monitored using techniques like liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to detect product formation. The result is a large, high-quality dataset of experimentally validated productive and non-productive enzyme-substrate pairs.

- Model Training and Validation: The curated experimental data was used to train the CATNIP machine learning model. The model was validated by its ability to predict new, previously unreported enzyme-substrate interactions within the superfamily.

Computational Identification of Specificity-Determining Residues

The EZSCAN tool offers a protocol for identifying key residues from sequence information alone [7].

- Sequence Data Curation: Collect two distinct sets of amino acid sequences from a comprehensive database (e.g., KEGG) for two related but functionally distinct enzyme subgroups (e.g., trypsin and chymotrypsin sequences).

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA): Perform a multiple sequence alignment of the combined sequence datasets to ensure positional correspondence of amino acid residues.

- Data Vectorization: Convert the aligned sequences into one-hot encoded vectors, where each residue position is represented as a binary vector indicating the presence of a specific amino acid.

- Machine Learning Classification: Train a logistic regression model to classify a given sequence as belonging to one subgroup or the other (e.g., trypsin vs. chymotrypsin) based on the amino acid type at each position in the alignment.

- Residue Importance Ranking: Analyze the trained model to identify the amino acid positions with the highest impact on the classification decision. The range between the maximum and minimum partial regression coefficients for each position serves as the primary metric for ranking the importance of residues in determining substrate specificity.

Experimental Validation by Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Predictions from tools like EZSCAN require experimental validation, often through mutagenesis [7].

- Mutagenesis Primer Design: Design oligonucleotide primers that encode the desired amino acid substitution(s) in the target enzyme gene.

- Plasmid Mutagenesis: Perform site-directed mutagenesis using a high-fidelity DNA polymerase on a plasmid containing the wild-type gene. The mutant plasmid is then transformed into a competent E. coli strain.

- Protein Expression and Purification: Express the wild-type and mutant proteins, typically via affinity chromatography, and confirm purity and stability (e.g., via SDS-PAGE and size-exclusion chromatography).

- Enzyme Activity Assay: Measure the catalytic activity of the wild-type and mutant enzymes against their native and non-native substrates. For example, after identifying key residues distinguishing Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) and Malate Dehydrogenase (MDH), mutations were introduced into LDH. The activity of the mutant was then assayed with its native substrate (pyruvate) and the new target substrate (oxaloacetate) to confirm a switch in substrate specificity.

Workflow Visualization for Specificity Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for analyzing substrate specificity in enzyme superfamilies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Enzyme Specificity Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| pET-28b(+) Vector | A common plasmid for high-level, inducible protein expression in E. coli. | Used for heterologous expression of the 314-member α-KG/Fe(II) enzyme library [32]. |

| α-Ketoglutarate (α-KG) | Essential co-substrate for α-KG/Fe(II)-dependent enzymes; consumed during the catalytic cycle. | A required component in all reaction screens for this enzyme family [32]. |

| Fe(II) Salts | Source of the catalytic iron metal center in the active site of metalloenzymes. | Used to reconstitute active enzymes in activity assays for α-KG-dependent enzymes and halogenases [4] [32]. |

| Sequence Similarity Network (SSN) | A computational tool to visualize and analyze sequence relationships within a protein family. | Used to design a phylogenetically diverse library for α-KG/Fe(II) enzymes, ensuring broad coverage of sequence space [32]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Enables the introduction of specific point mutations into a gene sequence. | Used to validate predictions from EZSCAN by mutating identified residues and testing for changes in substrate specificity [7]. |

| LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | An analytical technique for separating, detecting, and identifying reaction products. | The primary method for detecting product formation in high-throughput screens and validating new biocatalytic reactions [4] [32]. |

| Adenine dihydroiodide | Adenine dihydroiodide, CAS:73663-94-2, MF:C5H7I2N5, MW:390.95 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 11,15-Dimethylnonacosane | 11,15-Dimethylnonacosane C31H64 |

Advanced Techniques for Profiling and Applying Specificity Data

Enzyme kinetic analysis is fundamental to understanding catalytic mechanisms, substrate specificity, and cellular metabolism. Traditionally, classical enzyme assays have followed a one-substrate, one-enzyme approach, generating detailed kinetic parameters under controlled conditions. In contrast, multiplexed assays represent a paradigm shift, enabling simultaneous evaluation of multiple enzymatic activities or substrates within a single reaction mixture. This distinction is particularly critical in research on enzyme homologs, where subtle functional variations determine physiological roles and potential therapeutic applications.

The growing interest in multiplexed approaches stems from the recognition that enzymes frequently operate in complex metabolic networks with competing substrates rather than in isolation. As noted in studies of multi-substrate/product systems, "single target substrates matched with a single enzyme is the most direct and simplest system for investigating enzyme specificity in vitro," but this approach may fail to accurately predict enzyme behavior in vivo where multiple potential substrates compete for enzymatic attention [33]. This comprehensive guide examines both methodologies, providing researchers with the experimental frameworks and analytical tools needed to select the appropriate platform for their specific research objectives in comparative enzymology.

Fundamental Principles and Kinetic Considerations

Classical Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

The classical approach to enzyme kinetics is rooted in the Michaelis-Menten model, which describes enzyme-catalyzed reactions through the relationship between substrate concentration and reaction velocity. This model yields two fundamental parameters: the Michaelis constant (Km), which reflects the enzyme's affinity for its substrate, and the turnover number (kcat), which indicates the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme unit per time [34]. The specificity constant (kcat/Km) provides a composite measure of enzymatic efficiency that allows comparison between different enzyme-substrate pairs.

While this model has proven invaluable for understanding enzyme function, its applicability to multi-substrate systems is limited by its underlying assumptions. The Michaelis-Menten model assumes low enzyme concentrations relative to substrate and typically considers irreversible reactions without accounting for product inhibition or competing substrates [35]. These limitations have prompted the development of alternative models such as the total quasi-steady state assumption (tQSSA) and the differential quasi-steady state approximation (dQSSA), which offer improved accuracy for modeling complex biological networks without increasing parameter dimensionality [35].

Theoretical Basis of Multiplexed Analysis

Multiplexed assays for kinetic analysis operate on the principle of internal competition, where multiple substrates compete simultaneously for the same enzyme's active site. Under initial velocity conditions with equimolar substrates, the product abundances are directly proportional to the catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km) of the individual reactions [36]. This relationship holds true even when individual substrate concentrations exceed their Km values, providing a true measure of enzyme specificity.

However, when reactions proceed beyond the initial velocity regime—as is common in biocatalysis applications aiming for high conversion—the product profile becomes uncoupled from Michaelis-Menten kinetics and serves instead as a heuristic readout of overall reactivity [36]. In this context, both substrates and products can inhibit enzyme activity, with more reactive substrates often acting as strong competitive inhibitors of activity on poorer substrates. This complex interplay means that multiplexed assays can identify catalysts that maintain activity across multiple substrates under conditions more relevant to synthetic applications.

Experimental Platforms and Methodologies

Classical Assay Workflows

Classical enzyme kinetic analysis typically follows a standardized workflow beginning with enzyme purification to ensure that observed activities directly correspond to the enzyme of interest without interference from other cellular components. Researchers then perform a series of initial rate determinations across a range of substrate concentrations, with each reaction conducted separately under carefully controlled conditions of pH, temperature, and ionic strength [34]. The resulting data is fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation to extract Km and kcat values, enabling quantitative comparison of enzyme efficiency across different substrates or homologs.

The instrumentation for classical assays typically includes spectrophotometers or plate readers capable of detecting changes in absorbance, fluorescence, or luminescence over time. For example, the Infinite 200 PRO series plate reader supports various detection methods including light absorption, fluorescence intensity, time-resolved fluorescence, and fluorescence polarization, making it suitable for diverse enzyme assays [37]. These instruments enable researchers to monitor reaction progress continuously, providing comprehensive data sets for robust kinetic analysis. A significant advantage of this approach is the well-established theoretical framework for data interpretation and the ability to obtain precise, unambiguous kinetic parameters for individual enzyme-substrate pairs.

Multiplexed Assay Platforms

Multiplexed assays employ various technological platforms to simultaneously monitor multiple enzymatic activities, with mass spectrometry (MS) emerging as a particularly powerful tool. As demonstrated in a recent study profiling plant glycosyltransferases, liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) enabled screening of 85 enzymes against 453 natural products in a multiplexed format, resulting in nearly 40,000 potential reactions being assessed [38]. This approach leverages the consistent mass shift associated with glycosylation reactions, allowing identification of individual glycoside products from complex metabolite pools.

Other multiplexed platforms include electrochemiluminescence immunoassays (ECLIA), which use electrochemical and chemiluminescent principles for detection; Olink Proximity Extension Assay (PEA), which employs DNA-labeled antibody pairs for highly specific protein detection; and Luminex xMAP technology, which uses color-coded beads coated with specific capture antibodies [39]. The latter platform is particularly versatile, allowing simultaneous measurement of up to 500 targets for nucleic acids and approximately 80 targets for proteins in a single sample [39]. These platforms dramatically increase throughput while conserving precious samples, making them ideal for profiling enzyme homologs with potentially divergent substrate specificities.

Table 1: Comparison of Multiplexed Assay Platforms for Enzyme Kinetic Analysis

| Platform | Throughput Capacity | Key Applications | Detection Method | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS | 85 enzymes × 453 substrates [38] | Glycosyltransferase profiling, metabolic engineering | Mass spectrometry | Broad metabolite coverage, unambiguous product identification |

| Luminex xMAP | Up to 80 protein targets [39] | Cytokine analysis, signaling pathways, biomarker validation | Bead-based flow cytometry | High flexibility, validated assays, large dynamic range |

| ECLIA | Moderate to high multiplexing | Clinical biomarkers, therapeutic monitoring | Electrochemiluminescence | High sensitivity, wide dynamic range |

| Olink PEA | Up to 5,000+ proteins [39] | Proteomic profiling, biomarker discovery | qPCR or NGS | Exceptional specificity and sensitivity |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Throughput and Efficiency

The most apparent distinction between classical and multiplexed assays lies in their respective throughput capacities. Where classical assays require separate reactions for each enzyme-substrate combination, multiplexed platforms dramatically accelerate data acquisition. In a notable example, researchers implemented a substrate-multiplexed platform that screened 85 glycosyltransferases against 453 acceptor substrates pooled in sets of 40 compounds, resulting in 38,505 reactions being evaluated in a streamlined workflow [38]. This represents nearly two orders of magnitude improvement in throughput compared to classical approaches.

This enhanced throughput translates directly into practical efficiencies. Multiplexed assays conserve valuable sample volume—a critical consideration when working with precious biological specimens—by simultaneously measuring multiple analytes in the volume traditionally required for a single measurement [39]. Additionally, they significantly reduce hands-on time and reagent consumption while generating more comprehensive datasets. The cumulative effect is a substantially lower cost per data point, enabling researchers to explore enzyme specificity landscapes with unprecedented breadth and depth.

Data Quality and Kinetic Parameter Accuracy

Despite their throughput advantages, multiplexed assays present unique challenges in data quality and parameter accuracy. Classical assays excel in generating precise kinetic parameters (Km and kcat) under well-defined initial velocity conditions, making them indispensable for mechanistic studies. The recent development of structured kinetic datasets like SKiD (Structure-oriented Kinetics Dataset), which integrates kcat and Km values with corresponding 3D structural data, highlights the continuing value of carefully determined kinetic parameters [34].

Multiplexed assays may sacrifice some kinetic precision for increased scope, with product ratios in substrate competition experiments providing a relative measure of catalytic efficiency rather than exact kinetic parameters. However, when properly designed and validated, multiplexed platforms demonstrate excellent performance characteristics. For instance, the Invitrogen ProcartaPlex multiplex immunoassays exhibit intra-assay precision <15% CV, inter-assay precision <15% CV, and lot-to-lot consistency <30% CV, comparable to many traditional ELISAs [39]. The choice between approaches ultimately depends on the research objectives: classical assays for precise mechanistic insights, multiplexed platforms for comprehensive specificity profiling.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Classical vs. Multiplexed Assays

| Performance Metric | Classical Assays | Multiplexed Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low to moderate | High to very high |

| Kinetic Parameter Precision | High (direct Km/kcat determination) | Moderate (relative efficiency measures) |

| Sample Consumption | High (separate reactions per substrate) | Low (multiple analytes per reaction) |

| Data Comprehensiveness | Single substrate focus | Multi-substrate perspective |

| Technical Complexity | Low to moderate | Moderate to high |

| In Vivo Predictive Value | Limited for multi-substrate environments | Potentially higher for competitive environments |

Implementation in Enzyme Homolog Research

Experimental Design Considerations

Research comparing enzyme homologs presents unique challenges that influence assay selection. When designing kinetic studies, researchers must consider the degree of functional divergence among homologs, with closely related enzymes often amenable to multiplexed analysis while highly divergent homologs may require individual characterization. The availability of specific substrates also guides experimental design, as multiplexed approaches require substrates with distinct detection signatures (e.g., different mass shifts for MS-based detection).