Comparative Kinetics in Drug Development: Analyzing Bio-catalyzed vs. Chem-catalyzed Reaction Pathways

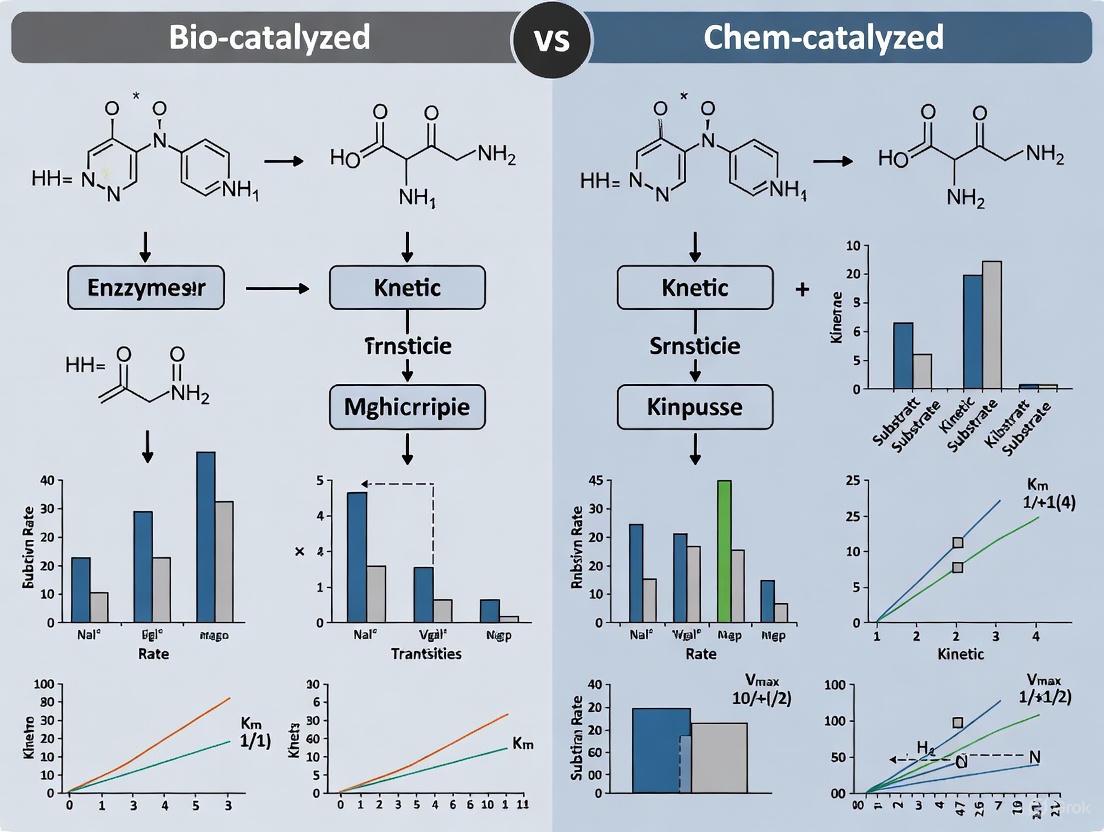

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the kinetics of bio-catalyzed and chem-catalyzed reactions, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Comparative Kinetics in Drug Development: Analyzing Bio-catalyzed vs. Chem-catalyzed Reaction Pathways

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the kinetics of bio-catalyzed and chem-catalyzed reactions, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational mechanisms distinguishing enzymatic from traditional chemical catalysis, detailing how parameters like catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) and Michaelis-Menten kinetics contrast with Langmuir-Hinshelwood models and transition metal catalysis. The scope extends to methodological approaches for measuring performance in pharmaceutical applications, including the critical assessment of operational stability, substrate selectivity, and productivity. It further addresses troubleshooting and optimization strategies for both catalyst types, covering enzyme immobilization, directed evolution, and ligand design for chemocatalysts. Finally, the article presents a validated, comparative framework for catalyst selection, benchmarking performance against industrial economic targets for active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) synthesis, integrating recent advances in protein engineering and sustainable process design.

Core Principles and Kinetic Frameworks: Unveiling the Mechanisms of Bio- and Chem-Catalysis

In the pursuit of efficient and sustainable chemical synthesis, particularly for pharmaceuticals, catalysis stands as a cornerstone technology. It enables the precise formation of complex molecular structures, often with multiple chiral centers, that are essential for modern drug development. Within this landscape, two distinct yet increasingly complementary catalyst classes have emerged: enzymes, nature's biological machines, and transition metal complexes, the workhorses of synthetic chemistry. Enzymes are protein-based biological catalysts that operate under mild, physiologically compatible conditions, leveraging intricate active sites to achieve remarkable specificity [1]. In contrast, transition metal complexes are synthetic or semi-synthetic constructs where a transition metal center, such as palladium, copper, or ruthenium, facilitates chemical transformations through processes like oxidative addition and reductive elimination [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data and methodologies, to inform research and development strategies.

Performance Comparison: A Data-Driven Analysis

The selection between enzymatic and transition metal catalysis depends on a multifaceted evaluation of performance characteristics. The following tables summarize key quantitative and qualitative metrics for easy comparison.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Catalytic Systems

| Performance Metric | Enzymatic Catalysis | Transition Metal Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Specificity | High; leads to minimal by-products [1] | Often lower; can result in more by-products [1] |

| Energy Consumption | Low (operates under mild conditions) [1] | High (often requires extreme T & P) [1] |

| Environmental Impact | Minimal; uses water, reduces hazardous waste [1] [3] | Significant; uses harsh chemicals/solvents [1] |

| Operational Costs | Lower (energy, waste disposal) [1] | Higher (energy, waste management) [1] |

| Typical Catalyst Loadings | Low (catalytic in substrate) | Variable (can require high loadings for certain reactions) |

| Development Timeline | Can be lengthy for enzyme engineering [3] | Often faster with pre-existing catalysts |

Table 2: Qualitative Operational Characteristics

| Characteristic | Enzymatic Catalysis | Transition Metal Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Medium | Often water or buffered solutions [3] | Mostly organic solvents [1] |

| Safety Profile | Safer; mild conditions, no heavy metals [1] [3] | Higher risk; hazardous chemicals, extreme conditions [1] |

| Functional Group Tolerance | Can be limited with non-natural substrates [4] | Broad, but can be compromised by sensitivity |

| Innovation & Development | Rapidly expanding with bioinformatics and directed evolution [1] [3] | Mature field with continuous ligand development [3] |

| Product Quality | High purity due to precision [1] | Can require complex purification [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Analysis

To generate comparative kinetic data, researchers employ standardized experimental setups. Below are detailed methodologies for assaying the activity of both catalyst types.

Protocol for Assessing a Cytochrome P450-Catalyzed Oxidation

This protocol is adapted from recent research on real-time capture of enzymatic intermediates [5].

- Objective: To monitor the kinetics and reactive intermediates of the CYP175A1-catalyzed oxidative dimerization of 1-methoxynaphthalene.

- Reagents:

- Purified N-terminal His-tagged CYP175A1 enzyme.

- 1-methoxynaphthalene substrate.

- Hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) as oxidant.

- 500 mM Ammonium Acetate (AA) buffer, pH 7.5.

- Equipment: High-resolution mass spectrometer (HRMS) with electrospray ionization (ESI) source, UV-Vis spectrophotometer, microfluidic infusion system.

- Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a 2 mL reaction vial, combine 5 µM CYP175A1 enzyme and 1 mM 1-methoxynaphthalene in 2 mL of 500 mM AA buffer.

- Initiation: Inject 40 µL of 250 mM H₂O₂ to initiate the reaction.

- Real-Time MS Monitoring: Continuously infuse the reaction mixture directly into the ESI-MS using a pressurized infusion setup. The applied voltage (+5 kV) creates microdroplets that stabilize transient intermediates.

- Data Collection:

- Operate the MS in full-scan mode to detect ions corresponding to the substrate (1-methoxynaphthalene, [M+H]âº), intermediates (e.g., 4-methoxy-1-naphthol, m/z 175.0750), and the final product (Russig's blue).

- Use tandem MS (MS/MS) to fragment and confirm the structure of detected intermediates.

- For radical intermediates, introduce a radical marker like TEMPO via a dual-channel infusion and use parallel reaction monitoring.

- Kinetic Analysis: Plot the time-dependent abundance of each ion to determine the sequence of intermediate formation and apparent reaction rates.

Protocol for Transition Metal-Catalyzed Lactam Synthesis

This protocol is based on methods for the multicomponent synthesis of benzo-fused γ-lactams [2].

- Objective: To evaluate the efficiency and enantioselectivity of a transition metal-catalyzed intramolecular C–H amination for lactam formation.

- Reagents:

- Transition metal catalyst (e.g., Pd, Cu, or Ru complex, ~5 mol%).

- Ligand (if required for the metal complex, e.g., chiral phosphines).

- Substrate (e.g., precursor containing both aryl and amine components).

- Suitable solvent (e.g., toluene, DMF).

- Additives (e.g., bases, oxidants).

- Equipment: Schlenk line for anaerobic reactions, gas chromatograph (GC) or high-performance liquid chromatator (HPLC), chiral HPLC column, NMR spectrometer.

- Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a flame-dried Schlenk tube under an inert atmosphere (Nâ‚‚ or Ar), combine the metal catalyst, ligand, and additive.

- Addition: Add the solvent and substrate via syringe.

- Initiation: Heat the reaction mixture to the specified temperature (e.g., 80-110 °C) with stirring.

- Reaction Monitoring:

- Withdraw aliquots at regular intervals.

- Quench the aliquots and analyze by GC or HPLC to monitor substrate consumption and product formation against a calibrated internal standard.

- Post-Reaction Analysis:

- After completion, cool the reaction mixture and purify the product via flash chromatography.

- Determine yield gravimetrically or via NMR.

- Analyze enantiomeric excess (ee) using chiral HPLC or by measuring optical rotation.

- Kinetic Analysis: Plot substrate concentration vs. time from the aliquot data to determine the reaction rate. Calculate turnover frequency (TOF) and number (TON).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful catalysis research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key items for both enzymatic and transition metal-catalyzed reactions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Catalysis Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| His-Tagged Enzymes | Allows for standardized purification via immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC). | Protein engineering and biocatalysis screening [5]. |

| Directed Evolution Kits | Commercial systems for rapid mutagenesis and screening to improve enzyme activity/stability. | Creating custom biocatalysts for non-natural reactions [3]. |

| Chiral Ligands | Induces asymmetry in transition metal-catalyzed reactions (e.g., BINAP, Duphos). | Asymmetric hydrogenation and C-C bond formation [3]. |

| Deuterated Solvents | Essential for NMR spectroscopy to monitor reaction progress and determine kinetics. | Reaction mechanism elucidation in both chemocatalysis and biocatalysis. |

| Stabilized Metal Precursors | Air- and moisture-stable sources of transition metals (e.g., Pd₂(dba)₃). | Ease of handling in catalyst preparation [2]. |

| EPR Spin Traps (e.g., TEMPO) | Chemically traps short-lived radical intermediates for detection and identification. | Probing radical mechanisms in photo- and biocatalysis [5]. |

| Heterogeneous Supports | Solid supports (e.g., polymers, silica) for immobilizing enzymes or metal catalysts. | Enabling catalyst recycling and continuous flow processes [1] [3]. |

| 2,2-Dimethyl-5-oxooctanal | 2,2-Dimethyl-5-oxooctanal|C8H14O2|RUO | 2,2-Dimethyl-5-oxooctanal is a high-purity keto-aldehyde for research, like organic synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| 6-Methylnona-4,8-dien-2-one | 6-Methylnona-4,8-dien-2-one|Research Chemical |

Visualizing Synergy: The Future of Integrated Catalysis

While often viewed as competitors, enzymes and transition metal complexes are increasingly used together in chemoenzymatic cascades. This approach combines the strengths of both worlds, minimizing intermediate isolation and streamlining synthesis. A significant challenge is overcoming incompatibilities in reaction media [4]. Advanced strategies like enzyme engineering, site-specific immobilization, and compartmentalization are being developed to facilitate their synergy.

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow and logical relationships in developing an integrated chemoenzymatic catalysis system, highlighting parallel strategies to overcome key challenges.

Both enzymes and transition metal complexes offer powerful, and often complementary, tools for catalytic synthesis. The choice between them is not a simple binary but a strategic decision based on the specific transformation, required selectivity, economic constraints, and environmental goals. Enzymes excel in stereoselective transformations under green chemistry principles, while transition metal complexes provide unparalleled versatility in bond-forming reactions. As the field advances, the integration of these catalytic worlds through chemoenzymatic cascades represents the most promising path forward, pushing the boundaries of synthetic efficiency and sustainability for drug development and beyond.

Catalytic processes are fundamental to chemical manufacturing, pharmaceutical synthesis, and numerous industrial transformations. Within this domain, two foundational kinetic models govern the understanding and optimization of distinct catalytic worlds: Michaelis-Menten kinetics for enzyme-catalyzed biocatalysis and Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetics for surface-mediated chemocatalysis. These models provide the mathematical framework for describing reaction rates, substrate binding, and product formation in their respective systems. While both models describe saturation kinetics where the reaction rate approaches a maximum velocity as substrate concentration increases, they originate from different scientific traditions and are applied to different catalytic contexts. Michaelis-Menten kinetics emerged from early 20th-century biochemistry through the work of Leonor Michaelis and Maud Menten, building on Victor Henri's earlier observations of enzyme-substrate interactions [6]. Conversely, the Langmuir-Hinshelwood model developed from Irving Langmuir's pioneering work in surface chemistry, which described the adsorption of gases onto solid surfaces [7]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these fundamental models, offering researchers and drug development professionals a structured analysis of their principles, applications, and experimental implementations to inform catalytic process design and optimization.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Michaelis-Menten Kinetics in Biocatalysis

The Michaelis-Menten model describes enzyme-catalyzed reactions through a fundamental mechanism where the enzyme (E) binds to its substrate (S) to form an enzyme-substrate complex (ES), which subsequently decomposes to yield the product (P) while regenerating the free enzyme. The general reaction scheme is represented as:

E + S ⇌ ES → E + P [8] [6]

This model operates under several key assumptions: (1) the enzyme concentration is much lower than the substrate concentration, (2) the system is in a steady state where the ES complex concentration remains constant, and (3) the reverse reaction of product to substrate is negligible, especially during initial rate measurements. The resulting rate equation describes how the reaction velocity (v) depends on the substrate concentration [a]:

v = (Vₘâ‚â‚› × [S]) / (Kₘ + [S]) [6]

where Vₘâ‚â‚› represents the maximum reaction rate achieved when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate, and Kₘ (the Michaelis constant) equals the substrate concentration at half of Vₘâ‚â‚›, reflecting the enzyme's affinity for the substrate—a lower Kₘ indicates higher affinity [8] [6]. The catalytic constant, kâ‚â‚œ (turnover number), defines the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per unit time, with Vₘâ‚â‚› = kâ‚â‚œ[Eâ‚€], where [Eâ‚€] is the total enzyme concentration [6].

Langmuir-Hinshelwood Kinetics in Chemocatalysis

The Langmuir-Hinshelwood model describes heterogeneous catalytic reactions where reactants adsorb onto a solid catalyst surface, undergo reaction, and then desorb as products. This mechanism originated from Langmuir's work on gas adsorption on surfaces and was later extended to describe catalytic reaction kinetics [7]. The model assumes: (1) adsorption creates a monolayer coverage on the surface, (2) the surface contains a finite number of identical adsorption sites, (3) adsorption is reversible, and (4) the reaction occurs between adsorbed species adjacent to one another on the surface.

The fundamental mechanism for a reaction between two adsorbed species A and B can be represented as:

A + * ⇌ A B + * ⇌ B A* + B* → AB + 2*

where * represents an active site on the catalyst surface, A* and B* represent adsorbed species, and AB is the product [7]. The rate expression derived from this mechanism depends on the adsorption equilibrium constants (KA, KB) and the surface reaction rate constant (k). For a single reactant A decomposing to product P, the rate equation takes the form:

v = (k KA [A]) / (1 + KA [A])

where k is the surface reaction rate constant, K_A is the adsorption equilibrium constant for A, and [A] is the concentration (or partial pressure for gases) of A [7]. The model was further refined in the Langmuir-Hinshelwood-Hougen-Watson (LHHW) formalism, which provides more comprehensive rate expressions accounting for various surface reaction mechanisms and activation energies [7].

Comparative Analysis: Mathematical Models and Parameters

The following tables summarize the key characteristics, parameters, and applications of both kinetic models, highlighting their similarities and fundamental differences.

Table 1: Fundamental Components of Kinetic Models

| Component | Michaelis-Menten (Biocatalysis) | Langmuir-Hinshelwood (Chemocatalysis) |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Type | Enzymes (biological macromolecules) | Solid surfaces (metals, metal oxides) |

| Reaction Phase | Typically homogeneous aqueous solutions | Heterogeneous (gas-solid or liquid-solid) |

| Active Sites | Enzyme active sites (specific 3D structures) | Surface adsorption sites (atomic arrays) |

| Binding Process | Substrate binding to form enzyme-substrate complex | Adsorption of reactants onto catalyst surface |

| Key Intermediate | Enzyme-substrate complex (ES) | Adsorbed species (A, B) |

| Rate-Determining Step | Typically decomposition of ES complex or chemical transformation | Often surface reaction between adsorbed species |

| Product Formation | Release from enzyme active site | Desorption from catalyst surface |

Table 2: Kinetic Parameters and Their Significance

| Parameter | Michaelis-Menten | Langmuir-Hinshelwood |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Rate | Vₘâ‚â‚› (maximum velocity) | k (surface reaction rate constant) |

| Binding/Affinity Constant | Kₘ (Michaelis constant) | KA, KB (adsorption equilibrium constants) |

| Catalyst Concentration | [E₀] (total enzyme concentration) | [*]ₜ (total active site concentration) |

| Specificity Metric | kâ‚â‚œ/Kₘ (specificity constant) | Selectivity factors (ratio of rate constants for parallel pathways) |

| Temperature Dependence | Complex due to enzyme denaturation at higher temperatures | Typically follows Arrhenius behavior until sintering occurs |

Table 3: Industrial Application Characteristics

| Characteristic | Biocatalysis (Michaelis-Menten) | Chemocatalysis (Langmuir-Hinshelwood) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Operating Conditions | Mild temperatures (20-40°C), aqueous solutions, narrow pH range | Often elevated temperatures/pressures, organic solvents or gas phase |

| Selectivity | High stereoselectivity and regioselectivity | Moderate to good selectivity, can be tuned with promoters |

| Stability | Limited operational stability, sensitive to conditions | Generally robust, can operate at harsh conditions |

| Reaction Examples | Asymmetric synthesis, pharmaceutical intermediates, fine chemicals | Bulk chemicals, petroleum refining, emissions control |

| Inhibition Effects | Substrate, product, competitive, uncompetitive inhibition | Reactant and product inhibition, site blocking |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Determining Michaelis-Menten Parameters

Protocol for Enzyme Kinetic Assays [8] [9]

Reaction Setup: Prepare a series of reactions with fixed enzyme concentration ([Eâ‚€]) and varying substrate concentrations ([S]). The enzyme concentration should be significantly lower than the lowest substrate concentration to satisfy the steady-state assumption.

Initial Rate Measurements: For each substrate concentration, measure the initial velocity (vâ‚€) of product formation or substrate depletion. Initial rates are crucial to avoid complications from product inhibition, reverse reaction, or enzyme denaturation over time.

Buffer Conditions: Maintain constant pH, temperature, and ionic strength using appropriate buffer systems. These factors significantly impact enzyme activity and stability.

Data Collection: Monitor the reaction progress using appropriate analytical techniques (spectrophotometry, HPLC, etc.) to determine the initial linear rate for each substrate concentration.

Parameter Estimation: Plot vâ‚€ versus [S] to obtain the characteristic hyperbolic curve. Estimate Vₘâ‚â‚› and Kₘ using nonlinear regression of the untransformed data, or using linearized plots such as Lineweaver-Burk (1/v vs. 1/[S]), Eadie-Hofstee (v vs. v/[S]), or Hanes-Woolf ([S]/v vs. [S]).

Validation: Verify that the data fit the Michaelis-Menten model and check for potential deviations indicating inhibition, allosteric effects, or other complexities.

Advanced Application in Biocatalysis [10]

For complex biocatalytic systems such as the dual-enzyme cascade for synthesizing the atorvastatin precursor (3R,5R)-2, kinetic modeling involves:

- Constructing kinetic models for each enzyme (aldo-keto reductase and glucose dehydrogenase)

- Accounting for cofactor regeneration kinetics

- Identifying rate-limiting steps through model-guided analysis

- Iteratively engineering biocatalysts based on kinetic limitations

Determining Langmuir-Hinshelwood Parameters

Protocol for Heterogeneous Catalyst Kinetics [7]

Adsorption Studies: First, characterize the adsorption behavior of individual reactants on the catalyst surface using techniques such as temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) or adsorption isotherms to determine adsorption equilibrium constants (KA, KB).

Reaction Rate Measurements: Conduct kinetic experiments by exposing the catalyst to reactant mixtures at varying concentrations (or partial pressures for gases) and measuring initial reaction rates.

Elimination of Mass Transfer Effects: Ensure that the measured rates are not influenced by external or internal mass transfer limitations by testing different catalyst particle sizes and agitation rates or flow conditions.

Systematic Variation: Systematically vary the concentration of one reactant while keeping others constant to determine the reaction order with respect to each reactant.

Model Fitting: Fit the experimental rate data to the proposed Langmuir-Hinshelwood rate expression using nonlinear regression techniques.

Parameter Estimation: Extract the kinetic parameters (rate constants, adsorption equilibrium constants) from the best-fit model.

Validation: Test the model's predictive capability by comparing predicted and experimental rates under conditions not used in the parameter estimation.

Reaction Mechanism Diagrams

Diagram 1: Comparative reaction mechanisms for Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetics (top) and Langmuir-Hinshelwood surface kinetics (bottom).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Kinetic Studies | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzymes | Biocatalyst for reaction rate determination | Michaelis-Menten kinetics; enzyme activity assays |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts | Solid surfaces for adsorption and reaction | Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetics; surface reaction studies |

| Cofactors (NAD(P)H, ATP, etc.) | Essential partners for enzyme catalysis | Oxidoreductase, kinase, and transferase assays |

| Buffer Systems | Maintain constant pH for enzyme activity | Biocatalysis optimization; pH-profile studies |

| Spectrophotometric Assays | Monitor substrate depletion or product formation | Initial rate measurements for both kinetic models |

| Chromatography Systems (HPLC, GC) | Quantitative analysis of reactants and products | Verification of conversion and selectivity |

| Adsorption Measurement Apparatus | Quantify reactant adsorption on surfaces | Determination of adsorption isotherms |

| Stopped-Flow Instruments | Measure very fast initial reaction rates | Pre-steady-state kinetic analysis |

| Oxaziridine-3-carbonitrile | Oxaziridine-3-carbonitrile|Research Chemical | Oxaziridine-3-carbonitrile is a versatile reagent for research (RUO). It is For Research Use Only. Not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic uses. |

| 2,9-Dimethyldecanedinitrile | 2,9-Dimethyldecanedinitrile|C14H24N2|For Research | High-purity 2,9-Dimethyldecanedinitrile for research applications. This product is for laboratory research use only (RUO) and not for human use. |

Application Case Studies

Biocatalysis: Pharmaceutical Synthesis with Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

A compelling application of Michaelis-Menten kinetics in pharmaceutical development is the synthesis of tert-butyl 6-cyano-(3R,5R)-dihydroxyhexanoate, a key chiral diol precursor of atorvastatin (Lipitor). This process employs a dual-enzyme system consisting of an aldo-keto reductase (AKR) for asymmetric reduction and glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) for cofactor regeneration [10].

Kinetic Challenge: The system required understanding the coupling efficiency between the two enzymes and identifying rate-limiting steps for process optimization.

Solution: Researchers developed a double-substrate ordered Bi-Bi kinetic model for the AKR and GDH-coupled bioreaction system. Through reaction-kinetic model-guided biocatalyst engineering, they implemented an iterative cycle of "kinetic model construction, limiting factor analysis, and biocatalyst engineering" [10].

Results: This approach enabled directed evolution of enzymes with improved catalytic efficiency, significantly enhancing the space-time yield of the atorvastatin precursor in both flask-scale and 50L bioreactor demonstrations [10].

Chemocatalysis: Surface Reactions with Langmuir-Hinshelwood Kinetics

The Langmuir-Hinshelwood model finds extensive application in heterogeneous catalytic processes, such as hydrogenation reactions, oxidation catalysis, and emissions control systems. The model provides the fundamental framework for understanding how reactants interact on catalyst surfaces and how surface coverage controls reaction rates.

Industrial Relevance: These principles guide the design of catalysts for numerous chemical processes, from petroleum refining to fine chemical synthesis [7]. The model helps engineers optimize catalyst composition, structure, and operating conditions to maximize reaction rates and selectivity.

Advanced Development: The Langmuir-Hinshelwood-Hougen-Watson (LHHW) extension of the model provides comprehensive rate expressions that account for complex surface reaction mechanisms, activation barriers, and the influence of surface coverage on reaction kinetics [7].

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The convergence of biocatalysis and chemocatalysis represents an emerging frontier in catalytic process development. Recent advances focus on combining the strengths of both catalytic approaches in chemo-biocascade reactions [11]. However, significant challenges remain in reconciling the different optimal operating conditions for enzymes and chemical catalysts.

Integration Strategies: Metal-organic framework micro-nanoreactors (MOF-MNRs) have been developed to spatially separate incompatible chemo- and biocatalysts while allowing controlled communication between them [11]. These systems enable concurrent chemo-biocatalysis by protecting sensitive enzymes while maintaining the activity of chemical catalysts under aqueous conditions.

Reaction Engineering: There is growing recognition that systematic reaction engineering approaches, long applied to chemical catalytic processes, are equally essential for advancing biocatalytic applications [9]. This includes developing kinetic models of sufficient accuracy for bioreactor design and integrating protein engineering with process optimization.

Kinetic Modeling Advances: Future research needs to focus on rapid methods for collecting kinetic data at sufficient accuracy for effective design of biocatalytic processes [9]. This includes accounting for the complex inhibition patterns that emerge at the high substrate concentrations required for industrial processes, far exceeding those found in natural biological systems.

As both kinetic modeling approaches continue to evolve, their intelligent integration and application will drive innovations in sustainable chemical synthesis, pharmaceutical manufacturing, and energy conversion technologies.

In the comparative analysis of bio-catalyzed and chem-catalyzed reactions, a deep understanding of distinct kinetic parameters is paramount for researchers and process developers. While kcat, KM, and the specificity constant (kcat/KM) form the bedrock of enzyme kinetics, Turnover Frequency (TOF) is a central metric in chemocatalysis. This guide provides an objective comparison of these parameters, underpinned by experimental data and methodologies, to inform catalyst selection and evaluation.

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

The kinetic parameters used to describe enzyme catalysts and traditional chemocatalysts, while conceptually similar in their aim to quantify efficiency, originate from different theoretical frameworks and are measured through distinct experimental protocols.

Core Enzyme Kinetic Parameters:

- kcat (Turnover Number): This parameter represents the maximal number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per unit of time when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate [12]. It is a first-order rate constant (units of sâ»Â¹ or minâ»Â¹) and reports on the catalytic power of the enzyme once the substrate is bound. The value of kcat is independent of enzyme concentration, as it is defined as ( \text{k}\text{cat} = \text{V}\text{max} / [\text{Enzyme}] ) [12].

- KM (Michaelis Constant): Operationally defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vmax, the KM is an inverse measure of the enzyme's apparent affinity for its substrate [13]. A lower KM value indicates that the enzyme requires a lower substrate concentration to reach half its maximum efficiency, signifying higher affinity [14].

- Specificity Constant (kcat/KM): This second-order rate constant (units of Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹) is the definitive metric for an enzyme's catalytic efficiency towards a specific substrate [13]. It incorporates both the efficiency of substrate binding (1/KM) and the catalytic rate once bound (kcat). A higher kcat/KM value indicates a more efficient enzyme, as it can effectively process substrate even at low concentrations.

Chemocatalysis Metric:

- Turnover Frequency (TOF): In chemocatalysis, TOF describes the number of catalytic cycles (turnovers) occurring per catalytic site per unit of time [11]. It is typically reported in units of hâ»Â¹ (hoursâ»Â¹). Unlike kcat, which is intrinsic to a specific enzyme-substrate pair, TOF is highly dependent on the precise reaction conditions, including temperature, pressure, and solvent.

Table 1: Core Definitions and Units of Key Kinetic Parameters

| Parameter | Definition | Typical Units | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| kcat | Turnover number; catalytic events per active site per second | sâ»Â¹, minâ»Â¹ | Enzyme Kinetics |

| KM | Substrate concentration at half Vmax; inverse measure of affinity | M (molar) | Enzyme Kinetics |

| Specificity Constant (kcat/KM) | Second-order rate constant for catalytic efficiency | Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹ | Enzyme Kinetics |

| Turnover Frequency (TOF) | Turnovers per catalytic site per hour | hâ»Â¹ | Chemocatalysis |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Determination

Accurate determination of these parameters requires careful experimental design. The following protocols outline established methods for both enzymatic and chemocatalytic systems.

Determining kcat and KM for Enzymes

The standard methodology for determining kcat and KM involves measuring the initial reaction velocity at varying substrate concentrations [12].

Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a series of reaction mixtures containing a fixed, known concentration of enzyme in an appropriate buffer. The substrate concentration is varied across the tubes, from values well below the expected KM to values intended to saturate the enzyme [12].

- Initial Velocity Measurement: For each reaction, initiate the catalysis and measure the initial rate of product formation (or substrate depletion) over a short, linear time period. This ensures the substrate concentration does not change significantly during the measurement, and product inhibition is minimal [15]. Techniques include spectrophotometry, fluorometry, or HPLC.

- Data Analysis: The resulting data of initial velocity (v) versus substrate concentration ([S]) typically produces a hyperbolic curve. The values for Vmax and KM can be extracted by fitting the data directly to the Michaelis-Menten equation (( v = (V{max} [S]) / (KM + [S]) )) using non-linear regression [15].

- Parameter Calculation: Once Vmax is determined, kcat is calculated using the formula ( \text{k}\text{cat} = \text{V}\text{max} / [\text{E}]_T ), where [E]T is the total concentration of active enzyme [12]. The specificity constant is then calculated as the ratio kcat/KM.

Visualization of Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data transformation from raw experimental measurements to the final kinetic parameters.

Determining Turnover Frequency (TOF) in Chemocatalysis

The measurement of TOF focuses on the activity per catalytic site, often under steady-state conditions.

Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: A known quantity of catalyst is introduced into a reaction vessel containing the reactants. The concentration of active catalytic sites must be known or determined through techniques like titration.

- Rate Measurement: The reaction is monitored, and the rate of product formation is measured under specific, controlled conditions (temperature, pressure, etc.). It is critical to measure the initial rate before significant catalyst deactivation or a drop in reactant concentration affects the turnover number.

- TOF Calculation: The TOF is calculated using the formula: ( \text{TOF} = \frac{\text{Moles of product formed}}{\text{(Moles of active sites)} \times \text{Time (hours)}} ). The "time" used is often the reaction time corresponding to the measured rate.

Comparative Analysis: Biocatalysis vs. Chemocatalysis

The choice between enzymatic and chemocatalytic routes often involves a trade-off between the remarkable specificity of biology and the robust reaction scope of chemistry.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Catalytic Parameters and Systems

| Feature | Biocatalysis (kcat/KM focus) | Chemocatalysis (TOF focus) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Range of kcat/TOF | Wide range (e.g., 1 to 10ⶠsâ»Â¹ for kcat) [12] | Highly variable, often from <1 to >10ⶠhâ»Â¹ |

| Typical Range of KM | µM to mM, highly substrate-dependent [16] | Not applicable |

| Influencing Factors | pH, temperature, enzyme integrity, substrate specificity | Ligand structure, metal center, solvent, temperature, pressure |

| Key Advantages | High stereo-/regio-selectivity; operates under mild, green conditions (often in water) [3] | Broad substrate scope; capable of high-temperature/pressure reactions; often easily tuned [3] |

| Inherent Limitations | Limited to natural-like reactions; can be inhibited by products/substrates; stability issues [16] | Can involve precious/toxic metals; may require stringent anaerobic conditions; lower selectivity can lead to by-products [3] |

Supporting Experimental Data: A study on engineering E. coli for vitamin B6 production highlights the challenges of low catalytic efficiencies in native enzymes. The key enzymes in the pathway (PdxA, PdxJ) were characterized by low kcat values and high KM values, resulting in low catalytic efficiency and limiting metabolic flux. This necessitated extensive protein engineering to improve these kinetic parameters for viable production [16].

Conversely, research into creating compatible chemo-biocatalytic systems demonstrates the performance of chemocatalysts. For example, one study developed a metal-organic framework micro-nanoreactor to spatially separate a biocatalyst from a chemocatalyst (Pt[(C6H5)3P]4). This setup was designed to protect both catalysts from mutual deactivation, allowing the TOF of the chemocatalyst to be enhanced under the aqueous, low-temperature conditions optimal for the enzyme, thereby matching the reaction dynamics of the two systems [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful kinetic analysis requires precise tools and materials. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Kinetic Analysis |

|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme (e.g., PdxA, PdxJ) | The catalyst of interest; requires high purity and accurately determined active concentration for kcat calculation [16]. |

| Chemocatalyst (e.g., Pt[(C6H5)3P]4) | The transition metal complex or heterogeneous catalyst for TOF measurement; active site concentration must be known [11]. |

| Varied Substrate Solutions | To generate the concentration gradient needed to determine the KM and Vmax (and thus kcat) of an enzymatic reaction [12]. |

| Appropriate Buffer Systems | To maintain constant pH, which is critical for enzyme stability and activity [16]. |

| Continuous Assay Components (e.g., Spectrophotometer) | To monitor the reaction in real-time, allowing for accurate determination of initial velocities [15]. |

| Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) Micro-nanoreactors | Advanced materials used to spatially separate incompatible chemo- and biocatalysts in cascade reactions, enabling accurate individual performance assessment [11]. |

| Computational Prediction Tools (e.g., UniKP) | A unified framework using pre-trained language models to predict enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat, KM) from protein sequence and substrate structure, accelerating enzyme screening and engineering [17]. |

| 1-tert-Butoxyoctan-2-ol | 1-tert-Butoxyoctan-2-ol, CAS:86108-32-9, MF:C12H26O2, MW:202.33 g/mol |

| 3-Methylfluoranthen-8-OL | 3-Methylfluoranthen-8-OL |

The direct numerical comparison of kcat (sâ»Â¹) and TOF (hâ»Â¹) is misleading due to different units and conceptual bases; a proper comparison requires contextualizing their values within the specific reaction and conditions. The distinction between the parameters is foundational: enzyme kinetics (kcat, KM, kcat/KM) provide a deep, mechanistic understanding of a highly specific catalyst, while TOF offers a practical measure of productivity for a broader-scope chemocatalyst.

The future of catalytic kinetics lies in the intelligent integration of both worlds. Advances in protein engineering allow for the optimization of kcat and KM in enzymes for non-natural reactions [16]. Simultaneously, novel reactor designs, such as MOF micro-nanoreactors, are solving compatibility issues, enabling efficient chemo-biocatalytic cascades by matching the TOF of chemocatalysts to enzymatic reaction dynamics [11]. Furthermore, the rise of computational tools like UniKP for predicting kinetic parameters is set to dramatically accelerate the pace of catalyst discovery and optimization for both biological and chemical systems [17].

The precise control of molecular asymmetry, or chirality, is a cornerstone of modern synthetic chemistry, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry where the biological activity of a molecule is often dictated by its three-dimensional structure. Two powerful paradigms have emerged for achieving high levels of stereocontrol: enzyme stereospecificity, honed by billions of years of evolution, and rational chiral ligand design in metal catalysis, a product of human ingenuity. Understanding the mechanistic basis, kinetic performance, and practical applications of these approaches is essential for researchers selecting the optimal catalytic strategy for a given transformation.

This guide provides a structured comparison of these two catalytic worlds, framing them within the broader context of comparative kinetics in bio-catalyzed versus chem-catalyzed reactions. We objectively examine their foundational principles, experimental characterization methods, and performance metrics through standardized data presentation, enabling scientists to make informed decisions in reaction design and catalyst selection.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Selectivity Origins

The mechanisms by which enzymes and chiral metal complexes achieve stereocontrol are fundamentally different, rooted in their distinct compositions and evolutionary histories.

Enzyme Stereospecificity

Enzyme stereospecificity is an inherent property arising from the precise three-dimensional arrangement of amino acids within the enzyme's active site. This creates a chiral environment that is exquisitely tuned to recognize and transform a single stereoisomer of a substrate.

- "Chiral Compartmentation": This concept describes how metabolic pathways can achieve operational compartmentation based not on physical membranes but on the stereospecificity of enzymes for their substrates. For instance, in mammalian erythrocytes, different stereoisomers of lactic acid generated by glycolysis (producing L-lactic acid) or the glyoxalase pathway (producing D-lactic acid) can be effectively compartmentalized due to the strict stereospecificity of the enzymes involved [18].

- Molecular Recognition: Enzyme active sites are structured to form multiple, simultaneous non-covalent interactions (hydrogen bonding, electrostatic, van der Waals, hydrophobic effects) with a specific substrate enantiomer. The mirror-image enantiomer fits poorly, leading to dramatically lower binding affinity and reaction rates.

- Reaction Mechanism: The catalytic process itself often involves stereospecific steps. A prime example is the action of amino acid racemases, which interconvert L- and D-amino acids. PLP-dependent racemases, such as alanine racemase, use a two-base mechanism involving a pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) cofactor. The enzyme's active site positions catalytic residues (e.g., a lysine and a tyrosine) to abstract a proton from one face of the substrate and donate a proton to the opposite face, enabling stereoinversion [19].

Chiral Ligand Design in Metal Catalysis

In asymmetric metal catalysis, stereocontrol is not inherent but is imposed externally by chiral organic molecules (ligands) coordinated to a metal center. The ligand framework constructs a steric and electronic environment around the metal that dictates the approach and orientation of the substrate.

- Ligand-Induced Chirality: This is the mainstream approach, where chiral ligands are solely responsible for transmitting chiral information. The ligand's structure controls the trajectory of substrate entry and binding at the metal center, favoring the formation of one product enantiomer over the other [20]. Thousands of chiral ligands, including privileged classes like BINAP, SALEN, and BOX, have been developed for this purpose [21] [22].

- Chiral-at-Metal Complexes: An emerging alternative employs achiral ligands that, due to their specific arrangement around the metal center, create an overall chiral complex where the metal itself is the stereogenic element. This "chiral-at-metal" strategy offers structural simplicity and can unlock unique catalytic properties and selectivities not accessible with traditional ligand designs [20] [21].

- Design Strategies: Recent advances in data science are revolutionizing ligand design. Machine learning (ML) models can now predict ligand performance and identify new patterns from complex datasets. Resources like the Chiral Ligand and Catalyst Database (CLC-DB), which contains 1,861 molecules with curated structural and property data, are accelerating the rational design of novel chiral catalysts [23].

Table 1: Fundamental Basis of Selectivity Comparison

| Feature | Enzyme Stereospecificity | Chiral Ligand Design |

|---|---|---|

| Origin of Selectivity | Pre-defined, evolved chiral active site | Engineered chiral environment via ligand/metal |

| Molecular Basis | Multiple, complementary non-covalent interactions | Primarily steric hindrance and electronic steering |

| Structural Scope | Highly specific for native substrates; can be engineered | Broadly tunable via ligand synthesis |

| Typical Mechanism | Often involves stereospecific proton transfers, nucleophilic attacks | Asymmetric induction via favored reaction trajectory |

| Evolution & Design | Directed evolution for new functions | Rational design & data-driven (ML) discovery |

Experimental Characterization and Kinetic Profiling

Quantifying catalytic performance and stereoselectivity requires rigorous kinetic measurements and advanced analytical techniques. Standardized protocols are vital for meaningful cross-platform comparisons.

Key Kinetic Parameters and Assays

The core kinetic parameters for both enzyme- and metal-catalyzed reactions are the turnover number (k_cat) and the Michaelis constant (K_m), or its equivalent in heterogeneous catalysis.

- For Enzyme Catalysis: The

k_cat(turnover number) represents the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time.K_m(Michaelis constant) is the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half ofV_max. Catalytic efficiency is often expressed ask_cat/K_m[24]. These parameters are typically determined by measuring initial reaction rates under varied substrate concentrations and fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten model. - For Metal Catalysis: The Turnover Frequency (TOF), analogous to

k_cat, is the number of substrate turnovers per catalytic site per unit time. The Enantiomeric Excess (e.e.) is the primary metric for stereoselectivity, calculated from the relative amounts of each enantiomer produced, typically measured by chiral chromatography or NMR spectroscopy [25].

Table 2: Standard Kinetic Parameters for Performance Comparison

| Parameter | Definition | Measurement Method | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

k_cat (sâ»Â¹) / TOF (hâ»Â¹) |

Turnover number/frequency | Progress curve analysis, initial rates | Intrinsic activity of the catalyst |

K_m (mM) / Apparent K_m |

Substrate affinity (enzyme) or binding (metal) | Variation of [substrate], Michaelis-Menten fit | Binding efficiency and saturation behavior |

k_cat/K_m (Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹) |

Specificity constant | Derived from k_cat and K_m |

Overall catalytic efficiency for a substrate |

| Enantiomeric Excess (e.e.) (%) | Purity of the chiral product | Chiral HPLC/GC, NMR with chiral solvating agents | Measure of stereoselectivity |

| Catalyst Loading (mol%) | Amount of catalyst used | - | Practical metric impacting cost and E-factor |

Structural and Data-Driven Characterization

- Enzyme-Substrate Complex Modeling: Understanding enzyme stereospecificity at an atomic level requires 3D structural data of enzyme-substrate complexes. Resources like the Structure-oriented Kinetics Dataset (SKiD) integrate kinetic parameters (

k_cat,K_m) with computationally modeled 3D structures of enzyme-substrate complexes. This allows researchers to correlate specific active site architectures and interactions with observed catalytic efficiency and selectivity [24]. - Ligand and Catalyst Databases: For metal catalysis, databases like CLC-DB provide curated information on chiral ligands and catalysts, including 2D/3D structures, chiral classifications, and computed molecular properties. This high-quality data is essential for training machine learning models to predict new catalytic structures and understand structure-selectivity relationships [23].

- Analytical Verification of Chirality: Techniques like NMR spectroscopy of stretched chiral hydrogels can be used to confirm the absolute configuration and enantiopurity of products, such as distinguishing between D- and L-lactic acid [18].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Comparative Catalyst Kinetics. This diagram outlines a standardized protocol for characterizing and comparing the performance of enzymatic and metal-based catalytic systems, from initial catalyst selection to final kinetic analysis.

Comparative Performance Data and Applications

The choice between enzymatic and chemical catalysis often hinges on practical performance metrics, operational stability, and applicability to the target reaction.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 3: Representative Performance Data for Selected Catalytic Systems

| Catalytic System | Reaction Type | Selectivity (e.e. %) | Turnover (k_cat / TOF) | Conditions | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine Racemase [19] | Stereoinversion (L-Ala D-Ala) | >99% (stereospecific) | k_cat ~ 2 sâ»Â¹ | Aqueous Buffer, 37°C | Perfect stereocontrol for metabolism |

| Palladium/PyDHIQ [25] | Conjugate Arylation | >90% e.e. | Not Specified | Organic Solvent | High e.e. for tetrasubstituted chromanones |

| Chiral-at-Ruthenium M8 [21] | Ring-Opening/Cross-Metathesis | 93% e.e. | 64 mol% yield | Organic Solvent | Structural simplicity (achiral ligands) |

| Chiral Paddle Wheel Rhodium [20] | Asymmetric C–H Activation | >90% e.e. | High yield reported | Varied | Inspired by enzyme (Cytochrome P450) |

Applications in Synthesis and Drug Development

Both systems are pivotal in synthesizing chiral intermediates for pharmaceuticals and other high-value chemicals.

- Enzymatic Catalysis: Leverages nature's biosynthetic pathways. The glyoxalase pathway naturally produces D-lactic acid with high stereospecificity [18]. Engineered enzymes are widely used in the synthesis of chiral amino acids, sugars, and other building blocks.

- Metal Catalysis: Offers broad synthetic flexibility. The design of novel chiral ligands like Pyridine-dihydroisoquinoline (PyDHIQ) enables efficient one-step synthesis of complex chiral scaffolds like tetrasubstituted chromanones, which possess numerous bioactivities [25]. Furthermore, the development of new, ultra-stable chiral molecules—such as those with oxygen/nitrogen-centered stereogenicity boasting half-lives of up to 84,000 years at room temperature—highlights the power of synthetic design to overcome inherent stability challenges in chiral drug development [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in comparative catalysis requires a suite of specialized reagents, databases, and computational tools.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example Sources / Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| BRENDA Database [24] | Comprehensive repository for enzyme kinetic data (k_cat, K_m). |

Reference for comparing native enzyme kinetics and substrate specificity. |

| SKiD Database [24] | Structure-oriented Kinetics Dataset linking enzyme 3D structures with kinetic parameters. | Modeling enzyme-substrate interactions; rational enzyme design. |

| Chiral Ligand & Catalyst Database (CLC-DB) [23] | Open-source database of 1,861 chiral ligands/catalysts with curated structures and properties. | Training ML models; rational ligand selection and design. |

| Chiral Stationary Phases (HPLC/GC) | Analytical columns for separation and quantification of enantiomers (e.e. determination). | Critical for measuring enantiomeric excess in both enzymatic and metal-catalyzed reactions. |

| PyDHIQ Ligands [25] | Chiral Pyridine-dihydroisoquinoline ligands for Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric conjugate arylation. | Synthesis of enantiomeriched tetrasubstituted chromanones. |

| Amino Acid Racemases [19] | Enzymes (PLP-dependent/independent) for interconverting L- and D-amino acids. | Production of non-natural D-amino acids for peptidoglycan mimics or pharmaceutical building blocks. |

| Gaussian Software [23] | Quantum chemistry package for computing molecular structures and properties. | Optimizing 3D ligand/catalyst structures using DFT (e.g., M062X/def2-SVP method). |

| RDKit [23] [24] | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Processing SMILES strings, generating 2D/3D molecular structures, and calculating descriptors. |

| 1-Octen-4-ol, 2-bromo- | 1-Octen-4-ol, 2-bromo-, CAS:83650-02-6, MF:C8H15BrO, MW:207.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Cyano-2-phenylpropanamide | 2-Cyano-2-phenylpropanamide | High-purity 2-Cyano-2-phenylpropanamide for life sciences research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The strategic choice between enzyme stereospecificity and chiral ligand design in metal catalysis is not a matter of declaring a universal winner but of matching the catalyst's inherent strengths to the application's specific demands. Enzyme stereospecificity offers unparalleled, evolutionarily perfected selectivity for specific metabolic transformations under mild conditions, as exemplified by the perfect chiral control in amino acid racemization [19]. Chiral ligand design, including the emerging chiral-at-metal paradigm, provides unparalleled flexibility, tunability, and the ability to mediate a vast range of abiotic transformations in synthetic organic chemistry [20] [21].

The future of catalytic selectivity lies not solely in one approach, but in their convergence. The integration of data-driven methodologies, such as machine learning powered by specialized databases like CLC-DB [23] and SKiD [24], is beginning to blur the lines between biological and chemical catalysis. By leveraging the deep mechanistic understanding of enzyme active sites to inspire the design of biomimetic metal complexes, and by applying the powerful tools of directed evolution to engineer and improve enzymes, scientists are forging a new hybrid discipline. This synergistic path promises to unlock unprecedented catalytic efficiencies and selectivities, accelerating the discovery and sustainable synthesis of the complex chiral molecules that will define the next generation of medicines and advanced materials.

The choice of reaction environment—aqueous media under mild conditions or organic solvents at elevated temperatures—is a pivotal decision in chemical synthesis, profoundly influencing reaction kinetics, selectivity, scalability, and environmental impact. This guide provides an objective comparison of these operational environments, with a specific focus on the comparative kinetics of bio-catalyzed versus chem-catalyzed reactions. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this analysis synthesizes current research data to inform strategic decisions in reaction optimization and process development.

Kinetic Comparison of Operational Environments

Quantitative Kinetic Parameter Analysis

The performance differential between bio-catalyzed and chem-catalyzed systems across operational environments can be quantified through key kinetic parameters. The following table summarizes experimental data characterizing these reactions.

Table 1: Comparative Kinetic Parameters for Bio- and Chem-Catalyzed Reactions in Different Environments

| Parameter | Bio-Catalysis (Aqueous, Mild) | Chem-Catalysis (Organic, Elevated T) | Kinetic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Temperature Range | 25-40°C (e.g., 37°C optimum for many human enzymes) [27] [28] | 50-150°C+ (Wide variation based on solvent and catalyst) | Higher temperature accelerates reaction rate but increases denaturation/deactivation risk in biocatalysis [27]. |

| Reaction Rate Trend with Temperature | Increases to an optimum, then declines sharply due to denaturation [28] | Generally increases steadily with temperature (Arrhenius-type behavior) | Biocatalysis has a narrow optimal window; chemocatalysis offers broader thermal acceleration. |

| pH Sensitivity | High (Sharp activity optimum, typically pH 5-8) [28] | Low to Moderate (Can often be performed across a wider pH range) | Biocatalysis requires careful buffering; chemocatalysis offers more flexibility. |

| Typical Michaelis Constant (Kₘ) | µM to mM range (High substrate binding affinity) [29] | Not typically characterized by Michaelis-Menten kinetics | Lower Kₘ indicates higher effective concentration of substrate at the catalyst active site in biocatalysis. |

| Typical Turnover Number (kcat) | 10²-10â´ sâ»Â¹ [29] | Highly variable (10â»Â²-10² sâ»Â¹ for many homogeneous catalysts) | A high kcat signifies a high catalytic efficiency for converting substrate to product. |

| Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/Kₘ) | 10â¶-10⸠Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹ (Extremely high efficiency) [29] | Generally several orders of magnitude lower than enzymatic efficiency | Quantifies the overall ability of a catalyst to convert substrate to product at low concentrations. |

Solubility and Solvent Properties

The reaction medium fundamentally dictates solute solubility and directly influences reaction kinetics and feasibility.

Table 2: Solubility and Environmental Impact of Operational Environments

| Factor | Aqueous, Mild Conditions | Organic Solvents, Elevated Temperatures |

|---|---|---|

| Solubility of Organic Compounds | Generally poor for non-polar organics; a key challenge in aqueous organic synthesis [30] [31] | Generally high for non-polar organics; solvents can be selected to optimize solute dissolution. |

| Solubility Prediction | Machine learning models (e.g., R² test values of 0.81-0.88) are increasingly reliable for aqueous systems [32]. | Prediction models exist, but experimental variability (aleatoric uncertainty of 0.5-1 log S) limits accuracy [33]. |

| "On Water" Effect | Significant rate accelerations for heterogeneous reactions of insoluble substrates due to unique properties at the organic-water interface [31]. | Not applicable. |

| Environmental & Safety Impact | Green, non-toxic, non-flammable, and environmentally benign [31]. | Many solvents are volatile organic compounds (VOCs) with associated toxicity, flammability, and environmental concerns [31]. |

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Analysis

Protocol for Determining Enzyme Kinetic Parameters

This methodology estimates the critical parameters Vmax and KM, which define the saturation kinetics of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction [29] [34].

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the substrate in an appropriate buffer, ensuring the pH is adjusted to the known optimum for the enzyme. Prepare a separate, standardized solution of the enzyme. Keep both solutions on ice until use.

- Initial Rate Measurements: In a series of reaction vessels (e.g., cuvettes), create solutions with a fixed, known concentration of the enzyme. Vary the concentration of the substrate across a wide range, typically from a value well below the expected KM to several times above it. Ensure the total reaction volume is consistent for all trials.

- Reaction Initiation and Monitoring: Start the reaction by adding the enzyme solution. Immediately monitor the formation of product or disappearance of substrate for a short initial period (usually 1-5 minutes) where the reaction rate is constant. Use an appropriate analytical method (e.g., spectrophotometry, HPLC).

- Data Analysis: Plot the initial reaction rate (vâ‚€) against the substrate concentration ([S]). The resulting hyperbolic curve can be fit using nonlinear regression to the Michaelis-Menten equation to directly obtain Vmax and KM [34]. Alternatively, linearized plots like Lineweaver-Burk can be used, though they are more susceptible to error propagation.

Protocol for Comparing Catalytic Efficiency Across Environments

This procedure allows for the direct comparison of a chemical catalyst in an organic solvent at elevated temperature versus a biocatalyst in water at mild temperatures.

- Standardized Reaction Selection: Select a model reaction that can be competently catalyzed by both a defined chemical catalyst (e.g., a transition metal complex) and an enzyme.

- Condition Optimization: For the chem-catalyzed reaction, identify the optimal organic solvent (e.g., toluene, DMF) and temperature. For the bio-catalyzed reaction, identify the optimal pH buffer and temperature (e.g., 37°C). These are the "best case" conditions for each system.

- Controlled Kinetic Experiment: Conduct the two reactions under their respective optimized conditions. Use the same initial molar concentration of catalyst and substrate in both setups.

- Quantitative Analysis: Withdraw aliquots at regular time intervals and quench the reaction. Analyze the aliquots to determine substrate conversion and product yield over time. Plot the conversion versus time to compare the reaction rates and final yields directly.

- Parameter Calculation: For the bio-catalyzed reaction, calculate kcat and KM as in Protocol 3.1. For the chem-catalyzed reaction, determine the apparent rate constant (kapp) by fitting the kinetic data to an appropriate model (e.g., pseudo-first-order). The ratio kcat/KM can then be compared to kapp for a direct efficiency comparison [29].

Workflow for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

The following diagram illustrates the robust, multi-step methodology for estimating kinetic parameters for biocatalytic reactions, moving beyond simple graphical analysis [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting experiments in the compared operational environments.

Table 3: Essential Reagent Solutions and Research Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Relevance to Operational Environment |

|---|---|---|

| pH Buffers | Maintain the optimal pH for enzyme activity and stability (e.g., phosphate, Tris buffers). | Critical for bio-catalysis in aqueous media due to high enzyme pH sensitivity [28]. |

| Engineered Enzymes | Bio-catalysts with enhanced stability, activity, or specificity. | Key reagent for aqueous, mild-condition synthesis. Often exhibit high catalytic efficiency (kcat/Kₘ) [29]. |

| Designer Surfactants | Form micelles in water to solubilize hydrophobic organic substrates [31]. | Enables "in water" chem-catalysis by creating a dispersed organic phase, expanding the scope of aqueous media. |

| Organic Solvents | Dissolve hydrophobic substrates and catalysts; can influence reaction rate and mechanism. | Essential for chem-catalysis. Selection is a key variable (e.g., polarity, boiling point for elevated T) [31]. |

| Homogeneous/Heterogeneous Catalysts | Chemical catalysts (e.g., metal complexes, solid acids) that promote bond formation/cleavage. | Key reagent for chem-catalysis in organic solvents. Performance is often temperature-dependent. |

| Kinetic Analysis Software | Performs nonlinear regression on progress curve data to fit kinetic models and extract parameters [34]. | Universal tool for rigorous comparison of kinetic performance across both environments. |

| 6-Chloro-2-methylhept-2-ene | 6-Chloro-2-methylhept-2-ene|C8H15Cl|80325-37-7 | 6-Chloro-2-methylhept-2-ene (CAS 80325-37-7) is a chemical intermediate for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Dimethylnitrophenanthrene | Dimethylnitrophenanthrene|High-Purity Reference Standard |

The operational environment is an integral determinant of catalytic efficiency, reaction scope, and process sustainability. Biocatalysis in aqueous, mild conditions offers unparalleled catalytic proficiency, exquisite selectivity, and a green profile but operates within a narrower window of temperature and pH. Chemocatalysis in organic solvents at elevated temperatures provides robust, broad-scope reactivity and simpler reaction engineering, though often with lower catalytic efficiency and greater environmental impact. The choice is not inherently superior but strategically aligned with the specific reaction constraints and process goals, a consideration paramount for researchers in drug development and synthetic chemistry.

Performance Metrics and Industrial Applications in Pharmaceutical Synthesis

In the evolving landscape of industrial biocatalysis, particularly within the pharmaceutical and specialty chemicals sectors, the accurate assessment of catalyst performance has become paramount for process development and commercialization. As biocatalysis matures as a field, researchers and process engineers require robust, standardized metrics that enable direct comparison between different biocatalysts and with traditional chemocatalytic alternatives [35] [36]. These metrics must provide meaningful insights into economic viability, scalability, and sustainability under industrially relevant conditions. While conventional measurement techniques have often focused on single parameters, a comprehensive evaluation requires the integrated assessment of three fundamental metrics: total turnover number (TTN) representing lifetime productivity, volumetric or specific productivity indicating reaction rate efficiency, and operational stability defining functional longevity under process conditions [35] [36]. These metrics collectively inform critical decisions in biocatalyst selection, process optimization, and economic modeling, especially as the field expands from high-value pharmaceuticals to medium-priced commodity chemicals where cost constraints become increasingly stringent [35].

The significance of these metrics extends beyond mere technical characterization to addressing core challenges in biocatalytic process development. Enzymes, as biological catalysts, possess inherent limitations in stability outside their natural physiological environments, often operating within narrow windows of temperature, pH, and solvent compatibility [35] [36]. Understanding and quantifying performance through TTN, productivity, and operational stability provides the foundation for protein engineering efforts, immobilization strategies, and reactor configuration selection, ultimately determining translational success from laboratory synthesis to industrial-scale production [35]. This review systematically examines these essential metrics, their methodological determination, and their application in comparative performance assessment between biocatalytic and chemocatalytic systems.

Fundamental Metrics for Biocatalyst Evaluation

Total Turnover Number (TTN): Lifetime Productivity Metric

The Total Turnover Number (TTN) represents a crucial dimensionless parameter defined as the total number of catalytic events performed by a single active site of an enzyme molecule throughout its operational lifespan [37]. Expressed mathematically, TTN equals the moles of product generated divided by the moles of biocatalyst used in a reaction, providing a direct correlation between catalyst input and product output that is particularly valuable for cost estimation in industrial processes [37]. This metric directly scales product yield to catalyst input, making it indispensable for economic modeling and cost-effectiveness assessments, especially when comparing engineered enzyme variants with similar activity but differing stability profiles [37].

For continuous processes utilizing soluble enzymes, TTN can be estimated as the quotient of the catalyst turnover number and the rate constant of spent catalyst replacement [37]. Importantly, research has demonstrated that TTN can be predicted from readily measurable biochemical quantities through the relationship TTN = kcat,obs/kd,obs, where kcat,obs is the observed catalytic constant and kd,obs is the observed deactivation rate constant, both measured under identical process conditions [37]. This calculation method applies to any enzyme whose thermal deactivation follows first-order kinetics, regardless of the number of unfolding intermediates, and circumvents potential problems associated with measuring specific catalyst output when a portion of the enzyme is already unfolded [37].

Productivity: Rate-Based Performance Metric

Productivity measures the rate of product formation per unit time and unit reactor volume (volumetric productivity) or per unit mass of catalyst (specific productivity) [35]. This metric captures the catalytic efficiency of the biocatalyst under specific process conditions, reflecting both intrinsic enzyme activity and the influence of reaction environment, mass transfer limitations, and substrate/product concentrations.

In industrial applications, productivity must be evaluated at sufficient substrate concentrations to minimize downstream product recovery costs, which typically means operating at substrate concentrations greatly in excess of KM [35] [36]. The traditional biochemical parameter of catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) becomes less relevant under these conditions, as it describes enzyme performance at substrate concentrations below KM [35] [36]. Exceptions where KM knowledge remains critical include: conversion of non-natural substrates with potentially high KM values; reactions with poorly water-soluble substrates supplied from a second organic phase; waste treatment applications where final substrate concentrations may be well below KM; and reactions requiring high substrate conversions where the final stages occur at substrate concentrations below KM [35] [36].

Operational Stability: Functional Longevity Metric

Operational stability defines the functional longevity of a biocatalyst under specific process conditions, representing its resistance to deactivation mechanisms such as thermal denaturation, inactivation by solvents, proteolysis, or poisoning by inhibitors [35] [38]. Unlike thermodynamic stability (often expressed as melting temperature, Tm), which measures the transition between native and unfolded states, operational stability reflects the retention of catalytic function over time in the actual reaction environment [35] [38].

This metric is typically quantified as the half-life (t½) of the biocatalyst, representing the time required for the enzyme to lose 50% of its initial activity under process conditions [37] [38]. The half-life can be determined through continuous reactor systems (e.g., plug-flow or continuous stirred tank reactors) or through repeated-batch methods where enzyme activity is measured over multiple reaction cycles [38]. For enzymes following first-order deactivation kinetics, the deactivation rate constant (kd) relates to half-life through the equation t½ = ln(2)/kd [37].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Biocatalyst Evaluation

| Metric | Definition | Typical Units | Significance | Measurement Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Turnover Number (TTN) | Moles product per mole catalyst over lifetime | Dimensionless | Lifetime productivity; cost estimation | Full catalyst lifetime under process conditions |

| Productivity | Product formation rate per unit volume or catalyst mass | g·Lâ»Â¹Â·hâ»Â¹ or g·gcatâ»Â¹Â·hâ»Â¹ | Process efficiency; reactor sizing | At substrate concentrations >> KM |

| Operational Stability | Retention of catalytic activity over time | Half-life (hours or days) | Catalyst longevity; replacement frequency | Under actual process conditions |

Experimental Methodologies for Metric Determination

Determining TTN Through Kinetic Measurements

The experimental determination of TTN requires monitoring both catalytic activity and deactivation kinetics under process-relevant conditions. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for TTN estimation:

Measure Observed Catalytic Constant (kcat,obs): Determine the reaction rate under substrate saturation conditions ([S] >> KM) at the desired process temperature and pH. Use initial rate measurements with varying enzyme concentrations to establish linearity. Calculate kcat,obs from the maximum velocity (Vmax) and total enzyme concentration ([E]total) using the relationship kcat,obs = Vmax/[E]total [37].

Determine Deactivation Rate Constant (kd,obs): Incubate the enzyme under process conditions (temperature, pH, solvent system) in the absence of substrate. At predetermined time intervals, withdraw aliquots and measure residual activity under standard assay conditions. Plot the natural logarithm of residual activity versus time; the slope of the linear regression provides kd,obs [37].

Calculate TTN: Compute TTN as the ratio TTN = kcat,obs/kd,obs. This relationship holds for enzymes whose thermal deactivation follows first-order kinetics, regardless of the number of unfolding intermediates [37].

For continuous processes, TTN can be validated by operating a bench-scale reactor and directly measuring total product formed versus catalyst consumed over the catalyst's operational lifetime [37] [35].

Assessing Operational Stability: Automated Repeated-Batch Method

Operational stability is optimally measured using methods that simulate industrial process conditions. An automated repeated-batch system provides a compromise between simple batch measurements and complex continuous reactor systems, enabling high-throughput determination of biocatalyst half-lives [38]:

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Operational Stability Assessment

Apparatus Setup: The system employs a reaction vessel with temperature control, automated sampling, and analytical detection (e.g., spectrophotometer, pH-stat, or gas uptake system). For carbonic anhydrase stability measurements, researchers have developed specialized systems monitoring CO2 hydration activity through pH changes or gas pressure variations [38].

Experimental Procedure:

- Prepare biocatalyst in appropriate reaction buffer under process conditions (temperature, pH).

- Initiate reaction by substrate addition at concentration relevant to industrial application.

- Monitor reaction progress continuously or through discrete sampling.

- Upon reaction completion or predetermined time point, automatically replace consumed substrate.

- Repeat cycles multiple times while recording reaction rate for each cycle.

- Continue until catalyst activity declines to ≤50% initial activity.

- Plot residual activity versus total operational time and determine half-life.

This method is particularly valuable for enzymes exhibiting substrate or product inhibition, where traditional batch methods with high initial substrate concentrations would be inappropriate [38]. The automated approach enables characterization of multiple enzymes in parallel with minimal manual intervention, with systems capable of stable operation for 36-48 hours [38].

Productivity Measurement Under Industrially Relevant Conditions

Productivity assessment requires careful attention to reaction conditions to ensure data relevance for scale-up:

Substrate Concentration: Use substrate concentrations significantly above KM (typically 10-100 × KM) to mimic industrial conditions where high product concentrations facilitate downstream processing [35] [36].

Reaction Monitoring: Employ continuous monitoring or frequent sampling to establish initial reaction rates without substrate depletion or significant product inhibition.

Environmental Parameters: Maintain strict control of temperature, pH, mixing intensity, and phase ratios (for multiphase systems) throughout the measurement.

Calculation: Determine volumetric productivity as (product concentration)/(reaction time × reactor volume). Specific productivity is calculated as (product mass)/(catalyst mass × time).

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Biocatalyst Performance Assessment

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Experiments | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biocatalyst | Purified enzyme or whole-cell preparation | Primary catalyst | Source (wild-type vs. engineered), purity, immobilization status |

| Substrate | High purity, specific stereochemistry when relevant | Reaction reactant | Solubility in reaction medium, potential inhibition effects |

| Buffer Components | Appropriate pKa for target pH | pH maintenance | Compatibility with enzyme and reaction, ionic strength effects |

| Cofactors | NAD(P)H, ATP, etc. as required | Enzyme activators | Recycling system requirements, stability under reaction conditions |

| Analytical Standards | Authentic product and intermediate samples | Quantification and identification | Availability, stability, detection characteristics |

| Immobilization Support | Functionalized resin, membrane, or particle | Catalyst carrier for immobilized systems | Pore size, functional groups, stability, cost |

Comparative Analysis: Biocatalysis vs. Chemocatalysis

Performance Metric Comparison

Direct comparison between biocatalytic and chemocatalytic systems reveals distinct advantages and limitations for each approach:

Total Turnover Number: Biocatalysts often demonstrate superior TTN for specific transformations, particularly those involving chiral synthesis or reactions under mild conditions. Engineered transaminases used in pharmaceutical synthesis achieve TTN values exceeding 100,000 in industrial applications [39]. However, chemocatalysts based on precious metals can sometimes achieve higher TTN in high-temperature processes where enzyme stability would be limited [3] [40].

Productivity: Biocatalytic systems typically operate at moderate temperatures (20-70°C) with high substrate specificity, enabling excellent productivity for target reactions without by-product formation [40] [1]. Chemocatalytic systems often require more extreme conditions (200-1000°C) but can achieve exceptionally high space-time yields in established processes like catalytic cracking [40].

Operational Stability: This represents a traditional challenge for biocatalysts, though significant advances have been made through protein engineering and immobilization [35] [39]. While chemocatalysts often maintain activity for months in continuous processes, biocatalysts typically require more frequent replacement, though engineered enzymes now maintain activity for weeks at elevated temperatures, rivaling some chemical catalyst performance [40].

Economic and Environmental Considerations

The application of these performance metrics directly influences process economics and sustainability: