Biosynthesis-Guided Discovery of Natural Products: Accelerating Drug Development with Synthetic Biology

This article explores the paradigm of biosynthesis-guided discovery, a transformative approach that leverages biosynthetic pathways and synthetic biology to efficiently uncover novel natural products with therapeutic potential.

Biosynthesis-Guided Discovery of Natural Products: Accelerating Drug Development with Synthetic Biology

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm of biosynthesis-guided discovery, a transformative approach that leverages biosynthetic pathways and synthetic biology to efficiently uncover novel natural products with therapeutic potential. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of linking genotype to chemical phenotype, core methodologies like genetically encoded biosensors and heterologous expression, and strategies for optimizing pathways and troubleshooting bottlenecks. It further examines the critical process of validating and comparing the biological activity and selectivity of newly discovered molecules, providing a comprehensive overview of how this integrated field is revitalizing natural product-based drug discovery for applications in diabetes, cancer, and beyond.

The Foundation of Biosynthesis-Guided Discovery: From Serendipity to Systematic Mining

Natural products provide privileged scaffolds for drug discovery, but their complex stereochemical architectures have often placed them beyond the reach of efficient synthetic preparation [1]. For decades, the discovery of bioactive natural products relied predominantly on traditional bioactivity screening—an approach characterized by the systematic extraction of compounds from biological sources followed by empirical testing against phenotypic assays or molecular targets. While this method yielded many foundational therapeutics, it suffers from inherent limitations including high rediscovery rates, limited chemical diversity, and neglect of silent biosynthetic gene clusters that are not expressed under laboratory conditions. These constraints have propelled a fundamental reorientation in discovery methodology toward biosynthesis-guided discovery, a paradigm that leverages genomic insights to predict chemical output and strategically access microbial natural products.

This technical guide examines the core principles, methodological framework, and practical implementation of biosynthesis-guided discovery, contextualizing it within the broader thesis that understanding and exploiting biosynthetic logic represents the most transformative development in natural products research of the past decade. Where traditional approaches treat the producing organism as a black box from which compounds are randomly isolated, biosynthesis-guided approaches open this box, using genetic blueprints to predict chemical output, manipulate biosynthetic pathways, and discover compounds with predefined structural properties.

Core Principles: From Genetic Blueprint to Chemical Structure

Biosynthesis-guided discovery operates on several foundational principles that distinguish it from traditional screening:

- Genetic Predictability Principle: The identity and sequence of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) reliably predict core structural features of their small molecule products, enabling in silico chemical prediction prior to isolation.

- Silent Cluster Activation: BGCs that are not expressed under laboratory conditions ("silent" or "cryptic" clusters) represent untapped chemical diversity that can be activated through targeted genetic or environmental manipulation.

- Biosynthetic Logic Integration: Understanding the enzymatic logic of natural product assembly—including stereochemical outcomes, modular synthesis, and post-assembly functionalization—enables rational discovery and engineering of analogues.

- Evolutionary Inference: Phylogenetic analysis of biosynthetic enzymes across species reveals evolutionary relationships that inform substrate specificity and chemical reactivity predictions.

The conceptual shift between traditional screening and biosynthesis-guided discovery represents a move from randomness to predictability, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Fundamental Contrast Between Traditional Screening and Biosynthesis-Guided Discovery

| Aspect | Traditional Screening | Biosynthesis-Guided Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Crude extracts from biological sources | Genomic sequences and predicted biosynthetic gene clusters |

| Discovery Driver | Bioactivity in assays | Genetic potential and biosynthetic logic |

| Chemical Prediction | Post-isolation structure elucidation | Pre-isolation in silico prediction |

| Silent Cluster Access | Limited to expressed compounds | Targeted activation through genetic/environmental manipulation |

| Engineering Potential | Limited to semi-synthesis | Pathway engineering and combinatorial biosynthesis |

| Key Limitation | High rediscovery rate | Requires high-quality genomic data and functional annotation |

Methodological Framework: The Technical Workflow

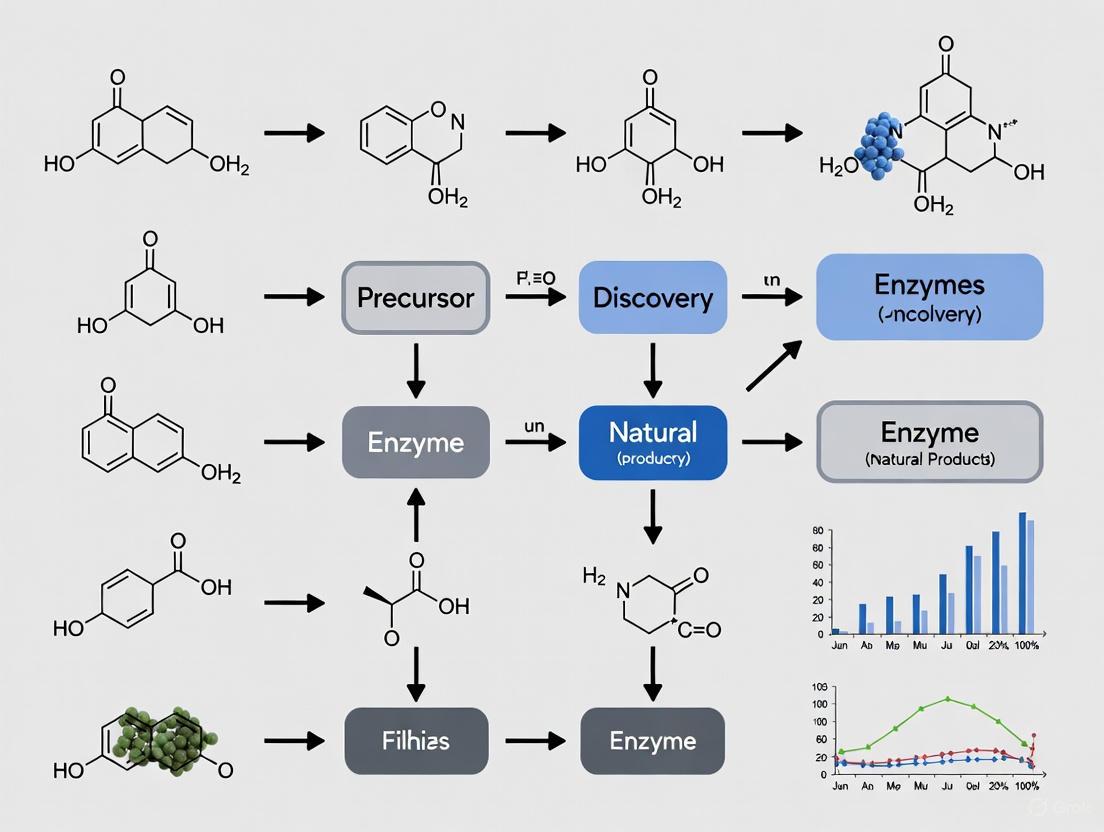

The operationalization of biosynthesis-guided discovery follows a systematic workflow that transforms genomic data into characterized natural products. The following diagram illustrates this integrated process:

Genome Mining and BGC Identification

The initial phase involves comprehensive genomic analysis to identify and annotate biosynthetic gene clusters:

- Genome Sequencing and Assembly: High-quality draft or complete genomes are generated using long-read (PacBio, Nanopore) or hybrid assembly approaches to ensure contiguous sequence through GC-rich and repetitive BGC regions.

- BGC Detection: Specialized algorithms (antiSMASH, PRISM, BAGEL) scan assembled genomes for signature genes of major natural product classes (nonribosomal peptide synthetases, polyketide synthases, ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides, terpenes).

- Cluster Boundary Delineation: Flanking genes, regulatory elements, and resistance mechanisms are identified to define complete cluster boundaries and potential regulatory networks.

In Silico Chemical Prediction

Bioinformatic analysis enables structural prediction prior to experimental work:

- Substrate Specificity Prediction: Adenylation domain specificity in NRPS systems (NRPSpredictor2, SANDPUMA) and acyltransferase domain specificity in PKS systems (PKSDB, SBSPKS) predict monomer incorporation.

- Collinearity Analysis: For modular systems, the linear organization of catalytic domains directly correlates with product assembly, enabling prediction of core scaffold structures.

- Post-assembly Modification Prediction: Identification of tailoring enzymes (oxidases, methyltransferases, glycosyltransferases) predicts functional group modifications and final product maturation.

Cluster Activation and Compound Production

Silent or poorly expressed BGCs require targeted activation strategies:

- Heterologous Expression: BGCs are cloned into optimized production hosts (Streptomyces coelicolor, Aspergillus nidulans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae) with strong constitutive promoters to bypass native regulation.

- Culture Manipulation: OSMAC (One Strain Many Compounds) approaches systematically vary cultivation parameters (media composition, temperature, aeration, co-culture) to induce silent clusters.

- Genetic Manipulation: CRISPR-based activation, promoter engineering, and transcription factor overexpression directly manipulate regulatory circuits controlling BGC expression.

- Precursor-Directed Biosynthesis: Feeding non-natural precursors to bypass pathway bottlenecks or generate analog libraries.

Compound Isolation and Characterization

Targeted isolation based on genetic predictions:

- Analytical Guided Fractionation: MS-based detection targets predicted molecular weights and fragmentation patterns, increasing efficiency over bioactivity-guided fractionation.

- Dereplication: UV, MS, and NMR spectra are compared against databases to identify known compounds early in the isolation process.

- Structure Elucidation: Advanced NMR techniques (HSQC, HMBC, ROESY) confirm predicted structural features and establish stereochemistry.

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies in Practice

Genome Mining for Terpene Cyclases

Terpene cyclases generate complex carbocyclic skeletons with multiple stereocenters—prime targets for biosynthesis-guided discovery [1].

Protocol: Identification and Characterization of Diterpene Synthases

Genome Sequencing and Annotation

- Sequence actinomycete genomes using Illumina NovaSeq (150bp paired-end) and PacBio Sequel II (long-read) for hybrid assembly

- Annotate using Prokka v1.14.6 with custom databases for terpenoid biosynthesis

- Identify terpene synthase genes using hidden Markov models (HMMs) for terpene synthase domains (PF03936, PF01397)

Phylogenetic Analysis

- Extract terpene synthase sequences and align with MAFFT v7.475

- Construct maximum-likelihood phylogeny with IQ-TREE v2.1.2 (1000 ultrafast bootstraps)

- Cluster sequences with characterized enzymes to predict cyclization mechanism

Heterologous Expression

- Amplify terpene synthase genes with native ribosomal binding sites

- Clone into pET28a(+) vector with C-terminal His₆-tag

- Transform E. coli BL21(DE3) for protein expression

- Induce with 0.1mM IPTG at 16°C for 20h

Enzyme Assay and Product Characterization

- Purify recombinant protein using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography

- Perform in vitro assays with 50μM geranylgeranyl diphosphate in 50mM HEPES (pH7.3), 10mM MgCl₂, 10% glycerol

- Extract with hexane and analyze by GC-MS (Agilent 8890/5977B)

- Compare retention indices and mass spectra with known diterpenes

Stereodivergent Enzyme Discovery

Recent genome mining has revealed enzymes exhibiting unusual stereoselectivities, expanding the enzymatic repertoire for constructing complex chiral architectures [1].

Protocol: Identification of Stereodivergent Oxygenases

Sequence-Based Discovery

- Compile seed sequences of characterized 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases

- Perform BLASTP search against microbial genomes with e-value cutoff 1e-10

- Identify divergent homologs with <60% sequence identity to characterized enzymes

Heterologous Expression and Screening

- Clone candidate genes into expression vector with strong constitutive promoter

- Transform Streptomyces lividans TK24 as heterologous host

- Culture in modified R5 medium for 5 days at 28°C

- Supplement with 1mM proline or pipecolinic acid substrates

Product Analysis and Stereochemical Determination

- Extract culture broth with ethyl acetate and concentrate

- Derivatize with diazomethane for GC-MS analysis

- Compare retention times to authentic standards on chiral stationary phase (Cyclosil-B column)

- Confirm absolute configuration by NMR with chiral shift reagents

Kinetic Characterization

- Measure initial velocities at varying substrate concentrations (0.1-5mM)

- Determine kcat and KM values by nonlinear regression

- Assess stereoselectivity by product ratio determination at 50% substrate conversion

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative Assessment of Discovery Approaches

The methodological shift from traditional screening to biosynthesis-guided approaches produces measurable differences in discovery outcomes, as quantified in Table 2.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Discovery Approach Efficiency

| Performance Metric | Traditional Screening | Biosynthesis-Guided Discovery | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel Compound Rate | 0.5-2% of tested extracts | 15-30% of prioritized BGCs | Comparative analysis of actinomycete screening [1] |

| Silent Cluster Access | <5% activation rate | 40-70% activation via heterologous expression | Heterologous expression studies [1] |

| Discovery Timeline | 12-24 months (extraction to structure) | 3-9 months (sequence to structure) | Methodology workflow comparisons [1] |

| Rediscovery Rate | 70-95% in common strains | <10% with genomic dereplication | Metagenomic analysis comparisons |

| Engineering Potential | Limited to semi-synthesis | Pathway engineering, combinatorial biosynthesis | Enzyme engineering studies [1] |

| Stereochemical Control | Empirical resolution | Predictive based on enzyme characterization | Stereodivergent enzyme studies [1] |

The efficiency advantage of biosynthesis-guided discovery is particularly evident in accessing compounds with specific stereochemical properties. Where traditional approaches rely on serendipitous discovery of desired stereoisomers, biosynthesis-guided methods can strategically identify enzymes with complementary stereoselectivities. For example, genome mining has revealed multiple proline hydroxylases with distinct regio- and stereoselectivities (cis-3-, cis-4-, trans-3-, and trans-4-hydroxylation) from various Streptomyces and Bacillus species, enabling systematic access to diverse hydroxyproline stereoisomers [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of biosynthesis-guided discovery requires specialized reagents and materials tailored to each workflow stage, as cataloged in Table 3.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biosynthesis-Guided Discovery

| Reagent/Material | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nextera XT DNA Library Kit | Fragmentation and adapter ligation for Illumina sequencing | Genome sequencing for BGC identification |

| pCAP01 Bacmid Vector | Heterologous expression of large BGCs in streptomycetes | Cluster activation in optimized hosts |

| antiSMASH 6.0 Database | Hidden Markov models for BGC boundary prediction | In silico chemical prediction from genomic data |

| Cytiva HisTrap HP Columns | Immobilized metal affinity chromatography | Recombinant enzyme purification for mechanistic studies |

| Chiralcel OD-H Column | Polysaccharide-based chiral stationary phase | Stereochemical analysis of enzyme products |

| Deuterated DMSO-d6 | NMR solvent for polar natural products | Structure elucidation of hydrophilic compounds |

| Silica Gel 60 (230-400 mesh) | Normal phase flash chromatography | Compound purification after fermentation |

| Restriction Enzyme BsaI | Golden Gate assembly for multigene constructs | Modular cloning of large BGCs |

| S. coelicolor M1152 | Engineered host with deleted native BGCs | Heterologous expression with reduced background |

| Authentic Standard Hydroxyprolines | Chiral reference compounds for stereochemical assignment | Configuration determination of enzyme products |

Pathway Visualization: Stereodivergent Enzyme Mechanisms

The discovery of stereodivergent enzymes through genome mining enables strategic access to diverse stereoisomers from identical substrates. The following diagram illustrates the mechanistic basis for stereodivergence in nonheme iron oxygenases, a enzyme family frequently identified through biosynthesis-guided approaches:

This mechanistic diversity, revealed through comparative genomics and enzyme characterization, enables the strategic selection of specific enzymes to produce desired stereoisomers. For example, genome mining has identified distinct proline hydroxylases from Kutzneria albida and other actinomycetes that exhibit complementary stereoselectivities, providing a toolbox for manufacturing specific hydroxyproline isomers that would be challenging to access through traditional synthesis [1].

Biosynthesis-guided discovery represents more than a technical advancement—it constitutes a fundamental philosophical shift in natural products research. By prioritizing genetic potential over expressed chemistry, this approach has dramatically expanded accessible chemical space, particularly for stereochemically complex scaffolds that remain challenging for synthetic chemistry. The integration of genomic data with structural prediction algorithms and heterologous expression systems has transformed natural product discovery from an empirical screening process to a rational, predictive science.

For drug development professionals, this paradigm offers strategic advantages: the ability to prioritize compounds based on predicted structural properties, access to previously inaccessible chemical space through silent cluster activation, and opportunities for bioinspired engineering of non-natural analogues. As genome sequencing becomes increasingly inexpensive and automated, and as bioinformatic prediction algorithms continue to improve, biosynthesis-guided approaches will likely become the dominant paradigm in natural product discovery, finally realizing the potential of microbial and plant genomes as the next frontier for drug discovery.

The genomic era has unveiled a profound discrepancy in natural product research: microbial and plant genomes are replete with biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) that far outpace the number of known metabolites. These BGCs represent a vast reservoir of untapped chemical diversity, offering tremendous potential for discovering new therapeutic agents and biochemical tools. The field has adopted the framework of "known unknowns" and "unknown unknowns" to categorize this hidden potential. Known unknowns refer to bioinformatically predicted BGCs for which the encoded natural product remains unidentified, while unknown unknowns represent BGCs that escape conventional prediction algorithms entirely, often because they lack recognizable core biosynthetic enzymes [2] [3].

This whitepaper explores the sophisticated methodologies developed to access this cryptic biosynthetic potential, framed within the context of biosynthesis-guided discovery. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these approaches is crucial for advancing natural product discovery into its next golden age. We provide a comprehensive technical overview of the experimental strategies, visualization tools, and reagent solutions driving this innovative field forward.

Defining the Landscape: Cryptic vs. Silent Gene Clusters

Precise terminology is essential for effective scientific communication in natural product research. According to Hoskisson and Seipke, the terms "cryptic" and "silent" should be disambiguated as follows [2]:

Cryptic BGCs: The term should describe BGCs and/or natural products that are hidden or unknown. This includes clusters where a natural product has been observed but its cognate BGC hasn't been identified (Unknown Knowns), and clusters where BGC expression is confirmed but the product remains unobserved under laboratory conditions (Known Unknowns).

Silent BGCs: This term should be reserved specifically for BGCs that are not expressed under standard laboratory conditions due to transcriptional or translational dormancy [2] [4].

The most challenging category, Unknown Unknowns, represents truly cryptic BGCs that lack functional annotation and escape detection by standard bioinformatic tools, potentially harboring completely novel biosynthetic mechanisms and compound classes [2].

Table 1: Classification of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

| Category | BGC Status | Product Status | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Known Knowns | Identified | Identified | Characterized BGCs linked to known natural products |

| Known Unknowns | Identified | Not observed | Bioinformatically-predicted BGCs with no identified product |

| Unknown Knowns | Not identified | Identified | Isolated natural products with unknown biosynthetic origin |

| Unknown Unknowns | Not identified | Not identified | BGCs lacking functional annotation that evade standard detection |

Quantitative Scope of the Opportunity

Genome sequencing initiatives have revealed the staggering scale of unexplored natural product diversity. In filamentous Actinobacteria alone, a study of 830 genomes identified >11,000 natural product BGCs representing >4,000 distinct chemical families [2]. Individual bacterial strains typically harbor 20-50 BGCs each, yet under standard laboratory conditions, only a fraction of these pathways are expressed [2] [4].

The model organism Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) provides a classic example, with 27 BGCs identified in its genome but only a handful of metabolites observed under conventional cultivation [4]. Similarly, in the fungal kingdom, Aspergillus nidulans possesses 52-63 predicted BGCs, while Neurospora crassa contains approximately 70 BGCs, most of which remain cryptic [5]. With over 1.2 million bacterial genomes and approximately 500,000 metagenomes now sequenced, the gap between predicted and characterized natural products continues to widen dramatically [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Assessment of Cryptic BGCs Across Organisms

| Organism Type | Representative Species | BGCs per Genome | Estimated Unexplored Diversity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteria | Streptomyces coelicolor | 27 | 17 out of 27 BGCs now assigned to metabolites |

| Fungi | Aspergillus nidulans | 52-63 | >97% of BGCs remain unlinked to products |

| Burkholderia | B. plantarii & B. gladioli | >20 each | Multiple novel metabolites discovered via HiTES |

| Plants | Various higher plants | ~20% of genes in specialized metabolism | Millions of predicted structures across 500,000 species |

Experimental Methodologies for Unlocking Cryptic BGCs

High-Throughput Elicitor Screening (HiTES) on Solid Media

HiTES represents a powerful forward chemical genetics approach for activating cryptic BGCs. The recently developed agar-based HiTES methodology is particularly effective for microbes whose natural habitat involves growth on solid surfaces [6].

Protocol: Agar-Based HiTES in 96-Well Format

Plate Preparation: Dispense liquid media into microtiter plates, followed by robotic addition of 320-1,000 structurally diverse candidate elicitors from libraries (e.g., FDA-approved drug library) [6].

Inoculation: Mix each well with bacterial inoculum containing 1% agar, maintained at 45°C for solubility but allowed to solidify at <35°C to facilitate even growth [6].

Incubation: Incubate plates for 3 days at optimal growth temperature (e.g., 30°C for Burkholderia species) [6].

Metabolite Extraction: Extract the content of each well with methanol, followed by filtration to remove particulate matter [6].

Metabolomic Analysis: Analyze filtered extracts using UPLC-Qtof-MS coupled with metabolic expression (MetEx) software. The MetEx output generates a three-dimensional map displaying m/z and intensity of observed metabolites as a function of the elicitor library [6].

Data Interpretation: Identify induced metabolites by binning detected ions above a selected abundance threshold and subtracting twice the average value for that bin in vehicle-treated controls. Positive values in the resulting difference matrix indicate induced features [6].

Validation and Scale-Up: Confirm production in larger agar plates (10-20 mL media) with optimal elicitor concentration determined through dose-response assays (typically 15-120 μM range) [6].

Genome Mining for Unknown-Unknown BGCs

Conventional genome mining targets BGCs with recognizable core enzymes (PKS, NRPS, etc.). Discovering unknown-unknown BGCs requires alternative strategies [3]:

Protocol: Identification of Unknown-Unknown BGCs

Cluster Criteria: Search for BGCs that lack canonical core enzymes but contain clusters of tailoring enzymes (oxidoreductases, methyltransferases, acyltransferases) and/or genes encoding hypothetical proteins (HPs) or domains of unknown function (DUFs) [3].

Comparative Genomics: Identify homologous BGCs across multiple species to highlight conserved open reading frames and define cluster boundaries [3].

Heterologous Expression: Express candidate BGCs in heterologous hosts (e.g., Aspergillus nidulans A1145 ΔEMΔST for fungal BGCs) and monitor for novel metabolites via LC-MS [3].

Gene Inactivation: Systematically inactivate individual genes within the BGC via knockout or knockdown approaches to correlate genes with metabolic features [3].

Biochemical Characterization: Purify and assay recombinant enzymes to validate predicted functions, particularly for novel scaffold-forming enzymes [3].

Transient Plant Expression Systems

For plant natural products, transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana provides a rapid alternative to microbial heterologous expression [7]:

Protocol: Agro-infiltration for Plant Natural Product Pathway Reconstitution

Vector Construction: Clone candidate biosynthetic genes into appropriate expression vectors compatible with Agrobacterium tumefaciens transformation [7].

Agrobacterium Preparation: Transform A. tumefaciens with expression constructs and culture to optimal density [7].

Infiltration: For small-scale work, manually infiltrate bacterial suspension into N. benthamiana leaves using a needleless syringe. For larger scale, vacuum infiltrate whole plants [7].

Incubation: Incubate plants for 3-5 days to allow for gene expression and metabolite production [7].

Metabolite Analysis: Extract and analyze leaf tissue for target compounds using LC-MS and NMR spectroscopy [7].

Discovery Pipeline for Cryptic Natural Products

Visualization of Biosynthetic Pathways and Workflows

Agar-Based HiTES Workflow

The HiTES approach on solid media has proven particularly effective for discovering metabolites that are not produced in liquid cultures, as demonstrated by the identification of burkethyls A and B from Burkholderia plantarii [6].

Agar-Based HiTES Workflow

Proposed Burkethyl Biosynthetic Pathway

Gene knockout studies and bioinformatic analysis of the bet BGC in Burkholderia plantarii have enabled proposal of a complete biosynthetic pathway for the unusual m-ethylbenzoyl-containing burkethyl compounds [6].

Burkethyl Biosynthetic Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Cryptic BGC Activation Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| FDA-Approved Drug Library | Elicitor library for HiTES; contains structurally diverse bioactive compounds | Used to identify ipratropium bromide, atropine, and zolmitriptan as inducers of burkethyl production [6] |

| antiSMASH Software | Genome mining platform for BGC identification and analysis | Identifies BGCs in bacterial and fungal genomes with customizable search parameters [2] [4] |

| MetEx Analytical Software | Metabolomics data analysis for HiTES; generates 3D metabolite maps | Used to visualize m/z features as a function of elicitor treatment in Burkholderia species [6] |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Delivery vector for transient plant expression systems | Enables heterologous expression of plant BGCs in N. benthamiana via agro-infiltration [7] |

| Nicotiana benthamiana | Model plant host for transient expression of biosynthetic pathways | Used for reconstitution of complex pathways like QS-21 (20 steps) [7] |

| Hypothetical Protein (HP) | Marker for unknown-unknown BGCs; indicates novel enzymatic functions | AnkA from A. thermomutatus identified as novel arginine cyclodipeptide synthase [3] |

The systematic exploration of cryptic biosynthetic pathways represents a paradigm shift in natural product discovery. By moving beyond traditional cultivation and screening approaches, researchers can now leverage genome mining, sophisticated elicitation strategies, and heterologous expression systems to access nature's full chemical repertoire. The distinction between known unknowns and unknown unknowns provides a valuable framework for prioritizing discovery efforts, with each category requiring specialized methodological approaches.

As sequencing technologies continue to advance and bioinformatic tools become more sophisticated, the potential for discovering novel therapeutic agents from cryptic BGCs continues to expand. The integration of machine learning with bioactivity prediction, coupled with high-throughput pathway refactoring capabilities, promises to further accelerate this field. For drug development professionals, these approaches offer exciting opportunities to access previously inaccessible chemical space, potentially yielding new classes of antibiotics, anticancer agents, and other therapeutics to address pressing medical needs.

Bioactive compounds, indispensable in medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology, are often encoded by Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)—groups of co-localized genes in microbial genomes that orchestrate the production of specialized metabolites [8]. Understanding the link between these genetic blueprints and the chemical molecules they produce is the cornerstone of modern natural product discovery. This paradigm shift from traditional activity-guided screening to biosynthesis-guided discovery leverages genomic data to uncover the vast, and largely silent, biosynthetic potential of microorganisms [9]. With the global ocean microbiome alone predicted to contain over 64,000 BGCs [8], efficient strategies to connect these clusters to their bioactive products are critical for accelerating the development of new therapeutics, such as novel antibiotics essential in the fight against antimicrobial resistance [10].

Fundamental Concepts: BGC Diversity and Classification

BGCs are categorized based on the core biosynthetic enzymes they encode, which determine the structural class of the resulting natural product. The major classes include:

- Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS): Large, modular enzyme assembly lines that synthesize peptides independent of the ribosome, producing a diverse array of bioactive compounds [8].

- Polyketide Synthases (PKS): Multi-domain enzymes that sequentially condense small carbon units into complex polyketide scaffolds, which include many clinically important drugs.

- Ribosomally synthesized and Post-translationally Modified Peptides (RiPPs): A rapidly growing class of peptides derived from a ribosomally synthesized precursor that is extensively modified by associated enzymes.

- Terpenoids: A large and structurally diverse family of compounds built from isoprene units.

- NI-Siderophores: Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS)-independent siderophores, which are small-molecule iron chelators crucial for microbial survival in iron-limited environments like the ocean [8].

The distribution of these BGCs is not uniform across taxa. Genomic studies reveal significant diversity; for instance, an analysis of marine bacteria identified 29 distinct BGC types, with NRPS, betalactone, and NI-siderophores being the most predominant [8]. Similarly, fungi in the genus Alternaria harbor an average of 34 BGCs per genome, with the specific profile of BGCs often correlating with phylogenetic relationships and ecological niche [11]. This taxonomic distribution provides the first layer of insight for prioritizing organisms in discovery campaigns.

Table 1: Prevalence of Major BGC Types in Recent Genomic Studies

| Study Organism / Group | Total Genomes Analyzed | Predominant BGC Types Identified | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Bacteria (21 species) [8] | 199 | NRPS, Betalactone, NI-Siderophore | 29 BGC types identified; vibrioferrin BGCs showed high structural variability. |

| Streptomyces albidoflavus VIP-1 [9] | 1 | PKS, NRPS, Terpene | The single marine strain's genome revealed a rich potential for novel bioactive compounds. |

| Fungi (Alternaria & relatives) [11] | 187 | PKS, NRPS, Other | An average of 34 BGCs per genome; distribution patterns correlated with phylogeny. |

Methodological Workflow: From Genome to Compound

The established pipeline for linking BGCs to bioactive molecules integrates bioinformatics, genetic analysis, and analytical chemistry in an iterative cycle.

Genome Mining and In Silico Prediction

The initial phase involves computationally identifying and characterizing BGCs from genomic data.

- BGC Prediction: Tools like antiSMASH (antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis SHell) are used for comprehensive BGC detection. The standard protocol involves running antiSMASH on a genomic file (e.g., GenBank or FASTA format) with default settings, enabling features like KnownClusterBlast and ClusterBlast to compare against validated BGC databases [8] [9].

- BGC Clustering and Prioritization: Identified BGCs are grouped into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) using tools like BiG-SCAPE (Biosynthetic Gene Similarity Clustering and Prospecting Engine). This networks analysis clusters BGCs based on protein domain sequence similarity, helping researchers prioritize clusters that are novel or widespread [8]. Clustering at different similarity cutoffs (e.g., 10% vs. 30%) can reveal fine-scale diversity or broader family relationships [8].

- Regulatory Gene Analysis: An emerging prioritization strategy involves analyzing regulatory genes, such as Streptomyces Antibiotic Regulatory Proteins (SARPs) and LuxR family regulators, which are often associated with the expression of bioactive compounds. Their presence can serve as a beacon for high-potential BGCs [10].

Genetic and Metabolic Validation

Following in silico prediction, wet-lab experiments are required to confirm the BGC's function.

- Gene Cluster Activation: For silent or cryptic BGCs, various strategies can be employed, including heterologous expression in a model host (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor), manipulation of culture conditions, or overexpression of pathway-specific regulatory genes [10] [9].

- Gene Inactivation: Targeted gene disruption or knockout is a definitive method to link a BGC to a compound. The loss of compound production in the mutant strain confirms the BGC's role. For example, the disruption of the

ugsAgene in a fungal BGC halted the production of unguisin cyclopeptides [12]. - Metabolite Analysis: Advanced analytical techniques such as Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) are used to characterize the chemical structure of the compound produced by the BGC. Correlating the presence of a BGC with the detection of its predicted metabolite is a key step in validation [12].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow connecting these stages.

Advanced Strategies: Engineering and Activation

Overcoming the challenge of silent BGCs requires advanced genetic and synthetic biology approaches.

Regulatory Gene Decoding

As noted in a study analyzing 440 Streptomyces genomes, investigating the protein domain architectures of regulatory genes can uncover strong associations with specific biosynthetic classes. This approach not only aids in prioritization but can also reveal 82 putative SARP-associated BGCs that were missed by standard antiSMASH analysis, highlighting its power for novel discovery [10].

Synthetic Biology and Enzyme Engineering

Combinatorial biosynthesis aims to rationally redesign BGCs to produce novel compounds. A key challenge is ensuring compatibility between enzymatic modules. Recent advances employ synthetic interface strategies to engineer modular enzyme assembly [13]. These include:

- Cognate Docking Domains: Natural interaction domains from PKS and NRPS systems.

- Synthetic Coiled-Coils: Engineered protein motifs that provide orthogonal binding.

- SpyTag/SpyCatcher: A protein ligation system that forms irreversible isopeptide bonds.

- Split Inteins: Self-splicing protein elements that facilitate post-translational fusion.

These synthetic interfaces function as standardized connectors, facilitating the programmable assembly of biosynthetic pathways and expanding accessible chemical space [13].

Case Studies in BGC-Driven Discovery

Vibrioferrin BGCs in Marine Bacteria

A comprehensive analysis of 199 marine bacterial genomes revealed significant genetic variability in vibrioferrin-producing NI-siderophore BGCs. While the core biosynthetic genes were conserved, the accessory genes showed high plasticity, influencing the resulting siderophore's structure and iron-chelation properties. BiG-SCAPE clustering showed these BGCs formed 12 distinct families at a 10% sequence similarity threshold, but merged into a single family at 30% similarity, demonstrating a spectrum of genetic diversity with implications for microbial competition and nutrient acquisition [8].

Unguisin Cyclopeptides from a Marine Fungus

The discovery of unguisin K from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus candidus exemplifies a complete BGC elucidation pathway. Researchers isolated the compound and then:

- Identified the candidate

ugsBGC. - Disrupted the key non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) gene

ugsA, which abolished production. - Characterized the function of enzymes

UgsB(a methyltransferase) andUgsC(an alanine racemase located outside the core BGC) through in vitro assays, fully elucidating the biosynthetic pathway [12].

Bioactive Streptomyces from a Red Sea Tunicate

The genome of Streptomyces albidoflavus VIP-1, isolated from the marine tunicate Molgula citrina, was sequenced and found to contain numerous BGCs for polyketides, non-ribosomal peptides, and terpenes [9]. This genomic potential correlated with observed bioactivity; crude extracts from the strain exhibited significant antimicrobial and antitumor activities in standard well-diffusion and MTT assays, respectively [9]. This case shows how genome mining can rapidly identify strains with high potential for subsequent compound discovery.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for BGC Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in BGC Research |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH [8] | Bioinformatics Software | Predicts and annotates BGCs in genomic sequences by comparing against known cluster databases. |

| BiG-SCAPE [8] | Bioinformatics Software | Clusters BGCs into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) based on protein domain sequence similarity. |

| MIBiG Database [8] | Reference Database | A curated repository of known BGCs used for comparative analysis and annotation. |

| SARP/LuxR Regulators [10] | Genetic Element | Regulatory genes used as markers to prioritize BGCs likely to produce bioactive compounds. |

| SpyTag/SpyCatcher [13] | Synthetic Biology Tool | A protein ligation system used to engineer modular enzyme assembly in PKS and NRPS pathways. |

| Ethyl Acetate [9] | Laboratory Solvent | Used for the extraction of secondary metabolites from microbial fermentation broths. |

| MTT Assay [9] | Bioactivity Test | A colorimetric assay for assessing cell viability and the antitumor activity of purified compounds or extracts. |

The strategic linking of BGCs to bioactive molecules represents a powerful, genomics-driven framework for natural product discovery. The core principles—comprehensive genome mining, phylogenetic and regulatory analysis, genetic validation, and metabolic profiling—provide a robust roadmap for researchers. Future progress will be fueled by deeper integration of artificial intelligence for predicting BGC function and product structure [14], advanced metabolon engineering to optimize pathway efficiency [14], and the continuous exploration of underexplored microbial habitats like the deep sea [9]. As these tools and datasets expand, the pace of discovering novel bioactive compounds with therapeutic potential will accelerate, solidifying the central role of BGCs in natural product research and drug development.

Natural products represent an invaluable source of therapeutic agents, with terpenoids, polyketides, and non-ribosomal peptides constituting three major classes renowned for their structural diversity and potent biological activities. This technical guide examines the biosynthetic principles, discovery methodologies, and engineering strategies for these compound classes within the framework of biosynthesis-guided natural product research. As emerging technologies transform this field, understanding the core biosynthetic logic becomes crucial for unlocking the vast potential of natural products in drug discovery and development. The integration of synthetic biology, heterologous expression, artificial intelligence, and automated high-throughput platforms is revolutionizing how researchers explore these complex molecules, offering solutions to longstanding challenges in structural elucidation, yield optimization, and compound accessibility [15] [16] [17].

Fundamental Biosynthetic Pathways

Core Building Blocks and Assembly Logic

The three natural product classes share a common paradigm: they are assembled from simple precursor molecules through enzyme-catalyzed reactions, yet each follows distinct biosynthetic logic with characteristic building blocks and assembly mechanisms.

Table 1: Core Biosynthetic Characteristics of Major Natural Product Classes

| Natural Product Class | Primary Building Blocks | Key Enzymatic Machinery | Representative Structures | Biological Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids | Isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP), Dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) | Prenyltransferases, Terpene synthases, Cytochrome P450s | Artemisinin, Paclitaxel | Antimalarial, Anticancer, Anti-inflammatory |

| Polyketides | Acetyl-CoA, Malonyl-CoA, Methylmalonyl-CoA | Polyketide synthases (PKSs) | Doxorubicin, Lovastatin | Antibiotic, Anticancer, Antihypercholesterolemic |

| Non-Ribosomal Peptides | Proteinogenic and non-proteinogenic amino acids | Non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) | Penicillin, Vancomycin | Antibiotic, Immunosuppressant, Antiviral |

Visualizing Core Biosynthetic Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental biosynthetic pathways for terpenoids, polyketides, and non-ribosomal peptides, highlighting their characteristic building blocks and key enzymatic stages:

Biosynthesis-Guided Discovery Approaches

Genome Mining and Heterologous Expression

The decentralization of biosynthetic genes in non-microbial organisms presents significant challenges for pathway elucidation. In Caenorhabditis elegans, nemamide biosynthesis requires at least seven genes distributed across the worm genome that are united by their common expression in specific neurons [18]. This distribution complicates the identification of complete biosynthetic pathways using conventional clustering algorithms.

Heterologous expression in genetically tractable hosts provides a powerful solution for accessing cryptic metabolic pathways. Established microbial platforms include:

- Streptomyces species (S. coelicolor, S. albus): Optimized for expressing actinomycete-derived pathways with high GC content [19] [17]

- Escherichia coli: Offers excellent genetic tools and rapid growth characteristics [19]

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Eukaryotic host suitable for fungal and plant pathways [17]

- Nicotiana benthamiana: Plant-based expression system particularly valuable for terpenoid pathways [20]

For terpenoid discovery, microbial high-yield terpene chassis engineered with optimal protein ratios through "Targeted Synthetic Metabolism" strategies enable stable and efficient synthesis of high-value terpenes [17]. The integration of rate-limiting enzymes such as HMGR or DXS boosts metabolic flux for improved product yields [20].

Artificial Intelligence and Pathway Prediction

Deep learning approaches are revolutionizing bio-retrosynthetic prediction, addressing the challenge that complete biosynthetic pathways are unknown for most natural products. BioNavi-NP employs transformer neural networks trained on biochemical reactions and implements an AND-OR tree-based planning algorithm for multi-step bio-retrosynthetic route prediction [21]. This system achieves a top-10 prediction accuracy of 60.6% for single-step biosynthetic reactions, significantly outperforming conventional rule-based approaches [21].

AI-driven enzyme function prediction facilitates the identification of terpenoid synthesis components with novel mechanisms, while automated high-throughput bio-foundry workstations accelerate the construction of comprehensive terpenoid libraries [15]. These technologies collectively address the critical bottlenecks of repetitive discoveries and low research throughput in natural product exploration.

Engineering and Combinatorial Biosynthesis

Rational reprogramming of biosynthetic machinery enables the production of unnatural metabolites with enhanced properties. Successful engineering strategies include:

Module swapping: Replacing the loading module of the avermectin PKS with the cyclohexanecarboxylic acid (CHC) loading module from the phoslactomycin PKS resulted in production of doramectin, a veterinary antiparasitic drug [16]

Precursor-directed biosynthesis: Chromosomal replacement of the chlorinase gene salL with the fluorinase gene flA in Salinispora tropica enabled biosynthesis of fluorosalinosporamide, a fluorinated analog of the anticancer agent salinosporamide A [16]

Termination module engineering: Swapping the unusual termination module from the glidonin NRPS to other nonribosomal peptide synthetases successfully added putrescine to the C-terminus of related peptides, improving their hydrophilicity and bioactivity [22]

These combinatorial biosynthetic approaches leverage Nature's strategies for structural diversification while overcoming the limitations of traditional synthetic chemistry for complex natural product scaffolds.

Experimental Methodologies

Heterologous Expression and Pathway Characterization

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for Natural Product Discovery

| Methodology | Technical Approach | Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Expression in Microbial Chassis | Cloning of biosynthetic gene clusters into optimized hosts (E. coli, S. cerevisiae, S. coelicolor) | Activation of silent gene clusters, Production enhancement, Pathway manipulation | Host compatibility, Precursor availability, Post-translational modifications |

| Transcriptome Mining | RNA sequencing (long-read and short-read technologies) followed by de novo transcriptome assembly | Identification of terpene synthases and modifying enzymes from non-model organisms | Tissue-specific expression patterns, Quality of assembly, Functional annotation |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing | Domain inactivation via point mutations (e.g., catalytic serine to alanine) | Elucidating biosynthetic steps, Intermediate trapping, Pathway mapping | Efficient delivery system, Off-target effects, Phenotypic screening |

| In Vitro Enzymatic Assays | Heterologous expression and purification of individual domains or dissected enzymes | Substrate specificity profiling, Kinetic characterization, Intermediate transfer studies | Protein solubility, Cofactor requirements, Maintenance of protein-protein interactions |

Protocol: Transcriptome Mining for Terpenoid Biosynthesis Enzymes

Based on the discovery and characterization of terpenoid biosynthesis enzymes from Daphniphyllum macropodum [20]:

Transcriptome Sequencing and Assembly

- Collect tissues of interest (e.g., leaf buds, flowers, immature leaves) and immediately freeze on dry ice

- Isolate DNA-depleted RNA using commercial kits (e.g., Direct-Zol RNA miniprep kit)

- Perform quality assessment (e.g., Agilent Tapestation system)

- Prepare libraries for both short-read (Illumina NovaSeq) and long-read (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) sequencing

- Execute de novo transcriptome assembly using specialized tools (e.g., Rattle for ONT reads)

- Polish assembly with Medaka (ONT reads) and Pilon (Illumina reads)

- Filter transcripts and identify open reading frames with Transdecoder

Identification of Terpenoid Biosynthesis Genes

- Annotate predicted peptides using InterProScan for domain annotations

- Perform BlastP searches against curated SwissProt database (E-value < 0.05)

- Identify terpenoid-related genes using InterPro accessions (e.g., IPR005630 for TPSs) and GO terms

- Validate candidates through blast matches to reference proteins (e.g., Arabidopsis TAIR10)

Functional Characterization via Heterologous Expression

- Amplify ORFs from cDNA with primers containing overlaps homologous to expression vectors (e.g., pHREAC)

- Co-express candidate genes with flux-enhancing enzymes (e.g., HMGR, DXS) in N. benthamiana

- Analyze products using GC-MS with authentic standards for comparison

- For triterpene cyclases, analyze products via LC-MS following extraction and derivatization

Protocol: Engineering NRPS Termination for C-Terminal Putrescine Addition

Based on the engineering of nonribosomal peptides with C-terminal putrescine [22]:

Identification and Characterization of Termination Module

- Bioinformatic analysis of NRPS termination module containing C domain, partial A domain (A*), T domain, and noncanonical TE domain

- Confirm absence of Stachelhaus codes in A* domain indicating non-functionality in amino acid activation

- Heterologously express and purify individual domains for in vitro biochemical assays

- Demonstrate that the C domain directly catalyzes condensation with putrescine

Module Swapping for Engineering Novel Peptides

- Amplify termination module using primers with appropriate restriction sites

- Clone into expression vectors containing recipient NRPS genes

- Express hybrid NRPS systems in heterologous hosts (e.g., Schlegelella brevitalea)

- Analyze products using LC-MS/MS to confirm putrescine incorporation

- Evaluate changes in bioactivity and hydrophilicity of modified peptides

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Natural Product Discovery

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Expression Systems | Platform for expressing biosynthetic pathways from diverse organisms | E. coli BL21, S. coelicolor, S. cerevisiae, N. benthamiana |

| Biosynthetic Gene Clusters | Genetic blueprints for natural product biosynthesis | Identified through genome mining, PCR-amplified or synthesized |

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms | Automated workflow for rapid gene cluster expression and product analysis | YES (Yeast Expression System) with robotic instrumentation |

| Bioinformatic Tools | In silico prediction of biosynthetic pathways and enzyme functions | BioNavi-NP, AntiSMASH, HMMER, Pfam, RetroPathRL |

| Precursor Compounds | Building blocks for natural product biosynthesis | IPP, DMAPP, Malonyl-CoA, Methylmalonyl-CoA, Amino acids |

| Analytical Standards | Reference compounds for structural identification | Valencene, Caryophyllene, Limonene, R-linalool (Sigma-Aldrich) |

| Enzyme Expression Vectors | Plasmid systems for heterologous protein production | pHREAC, pET series, customizable promoters and tags |

Integrated Discovery Workflow

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive biosynthesis-guided natural product discovery pipeline, integrating computational, molecular biology, and analytical approaches:

Biosynthesis-guided discovery represents a paradigm shift in natural product research, moving from traditional activity-guided isolation to targeted exploitation of biosynthetic logic. The integration of genomic mining, heterologous expression, combinatorial biosynthesis, and AI-driven prediction creates a powerful framework for accessing Nature's chemical diversity. As these technologies mature, we anticipate accelerated discovery of novel therapeutic candidates from terpenoids, polyketides, and non-ribosomal peptides, addressing the critical need for new chemical entities in drug development, particularly in combating antimicrobial resistance and complex diseases.

Future advancements will likely focus on refining pathway prediction algorithms, expanding the repertoire of heterologous hosts with customized metabolic capabilities, and developing more sophisticated engineering approaches for megasynthase manipulation. The continued convergence of biology, chemistry, and computational sciences will further solidify biosynthesis-guided discovery as an indispensable strategy in natural product research and development.

The discovery of bioactive natural products has been revolutionized by the advent of omics technologies, which provide powerful tools for elucidating complex biosynthetic pathways. Historically, the identification of metabolic pathways relied on labor-intensive biochemical methods, but the integration of genomics and transcriptomics has accelerated the pace and precision of discovery [23]. These technologies have become indispensable for mapping the genetic blueprint of valuable plant and microbial metabolites, enabling researchers to move from traditional bioactivity-guided isolation to targeted, gene-informed discovery strategies [24] [25]. This paradigm shift is particularly crucial in natural products research, where the diminishing returns of conventional approaches and high rediscovery rates of known compounds have created an urgent need for more efficient discovery methodologies [26] [27].

The fundamental challenge in natural product research lies in the complexity of biosynthetic pathways and the fact that many remain silent under standard laboratory conditions [26]. Omics technologies address this challenge by providing comprehensive datasets that reveal the intricate relationships between genes, their expression patterns, and the resulting metabolic profiles [23] [24]. This review examines how genomics and transcriptomics are being leveraged to identify and characterize biosynthetic pathways, with profound implications for drug discovery and development.

Genomic Foundations of Pathway Discovery

Genome Mining and Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Identification

Genome sequencing provides a complete blueprint of an organism's genetic capacity for natural product biosynthesis [25] [27]. The cornerstone of genomic approaches is the identification of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) – groups of co-localized genes encoding the enzymatic machinery for specific metabolic pathways [24] [26]. Early genomic studies revealed a surprising discrepancy: the number of detected BGCs far exceeds the number of known compounds from most organisms, suggesting extensive untapped biosynthetic potential [26] [25]. For instance, genome analysis of Streptomyces coelicolor uncovered significantly more BGCs than previously anticipated based on known metabolites [27].

Advanced bioinformatic tools have been developed to automate BGC detection and characterization. These tools leverage our growing understanding of biosynthetic logic to predict natural product assembly lines and their putative structures from gene sequences [26]. The table below summarizes key genomic tools and databases used in biosynthetic pathway identification:

Table 1: Key Bioinformatic Tools for Genomic Mining of Biosynthetic Pathways

| Tool/Database | Primary Function | Application Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | Detection & annotation of BGCs | Identification of novel BGCs in marine Streptomyces | [25] [27] |

| PRISM | Prediction of chemically structures from BGCs | Structural prediction of ribosomal peptides | [25] [27] |

| MIBiG | Repository of known BGCs | Reference database for BGC classification | [24] [25] |

| DeepBGC | Machine learning-based BGC detection | Discovery of novel BGC classes | [26] [27] |

| NP.searcher | Identification of natural product structures | Linking BGCs to known compounds | [27] |

Genomic Mining Strategies

Several specialized strategies have emerged to enhance the efficiency of genomic mining. Homology-based screening identifies candidate genes by searching for sequences similar to known biosynthetic enzymes, often using BLAST searches against curated databases [23]. This approach has successfully identified novel pathways for compounds such as spiroxindole alkaloids and benzylisoquinoline alkaloids [23].

Phylogeny-guided discovery examines the evolutionary relationships between biosynthetic genes across different species to identify conserved pathways and lineage-specific innovations [26]. This strategy has revealed how gene duplication and neofunctionalization contribute to metabolic diversity in plants [23].

Resistance gene-based mining targets self-resistance mechanisms that organisms employ to avoid toxicity from their own natural products, as these resistance genes are often co-localized with BGCs [26]. This approach successfully identified the thiolactomycin BGC in Salinispora strains and pyxidicyclins in Pyxidicoccus fallax [26].

Transcriptomic Approaches to Pathway Elucidation

Transcriptome Mining and Co-expression Analysis

Transcriptomics provides critical functional context to genomic blueprints by revealing when and where biosynthetic genes are active [23] [28]. Co-expression analysis identifies genes that show correlated expression patterns across different tissues, developmental stages, or experimental conditions, suggesting their involvement in related biological processes [23]. This approach has been instrumental in elucidating pathways for numerous plant natural products, including etoposide, colchicine, strychnine, and triterpenes [23].

The power of transcriptome mining is exemplified by recent work on plant ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs). Researchers optimized RNA-seq assembly pipelines to mine transcriptomes from 7,569 plant species, discovering novel macrocyclic analogs of the stephanotic acid scaffold with improved bioactivity against lung adenocarcinoma cells [28]. This large-scale approach demonstrates how transcriptome data can diversify the medicinal chemistry toolbox for natural product discovery.

Table 2: Transcriptomic Approaches in Biosynthetic Pathway Elucidation

| Method | Principle | Key Applications | Tools/Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-expression Analysis | Identifies genes with correlated expression | Linking uncharacterized genes to known pathways | Pearson correlation, self-organizing maps |

| Differential Expression | Compares gene expression under different conditions | Identifying pathway regulation in response to stimuli | RNA-seq analysis pipelines |

| Transcriptome Assembly | Reconstructs transcript sequences from RNA-seq reads | Gene discovery in non-model organisms | Trinity, SPAdes, MEGAHIT |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Profiles gene expression at single-cell resolution | Mapping spatial organization of pathways | Cell sorting, droplet-based sequencing |

Experimental Workflow for Transcriptome-Guided Discovery

A typical transcriptome-guided pathway discovery workflow involves multiple standardized steps [23] [28]:

Sample Collection: Tissues are selected based on metabolic profiling, often targeting organs or developmental stages with high accumulation of target compounds.

RNA Extraction: High-quality RNA is isolated using standardized kits, with quality verification via bioanalyzer systems.

Library Preparation and Sequencing: cDNA libraries are prepared using reverse transcriptase and adapter ligation, followed by sequencing on platforms such as Illumina.

Data Processing: Raw reads are quality-checked (FastQC) and trimmed (Trimmomatic) to remove adapters and low-quality bases.

Transcript Assembly: For non-model organisms without reference genomes, de novo assembly is performed using specialized assemblers. Recent benchmarking identified MEGAHIT as the most efficient assembler for plant RiPP discovery, balancing speed (fastest), memory usage (lowest), and accuracy in reconstructing precursor peptides [28].

Expression Analysis: Assembled transcripts are quantified and analyzed for co-expression patterns and differential expression.

Candidate Gene Selection: Genes showing correlation with metabolite abundance or known pathway genes are prioritized for functional characterization.

Integrated Omics Workflows

Multi-Omics Data Integration

The most powerful applications of omics technologies emerge from their integration, where genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic data are combined to create comprehensive pathway models [23] [24]. This integrated approach follows a logical progression from genetic potential to functional activity:

Genomics provides the blueprint of all possible biosynthetic capacities through BGC identification [24] [26]. Transcriptomics reveals which pathways are active under specific conditions and helps connect orphan BGCs to their metabolic products [23] [28]. Metabolomics completes the picture by characterizing the chemical structures of pathway intermediates and final products [24] [29].

Advanced computational methods are essential for integrating these diverse datasets. Machine learning algorithms can predict substrate specificity and reaction outcomes from enzyme sequences [23] [24]. Network-based approaches link genes to metabolites through correlation analysis, creating integrated knowledge networks that facilitate the identification of rate-limiting steps and regulatory bottlenecks [24] [29].

Visualization of Integrated Omics Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated omics workflow for biosynthetic pathway discovery:

Integrated Omics Workflow for Pathway Discovery

Implementation and Experimental Considerations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of omics-guided pathway discovery requires specialized reagents and platforms. The table below outlines key solutions and their applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Omics Studies

| Category | Specific Solutions | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Isolation | TRIzol/Plant RNA kits | High-quality RNA/DNA extraction from diverse sample types |

| Sequencing Library Prep | Illumina TruSeq kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries for genomics/transcriptomics |

| Heterologous Expression | pET vectors, Gateway system | Cloning and expression of candidate genes in hosts like E. coli and yeast |

| Transient Expression | Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains | Rapid functional validation in Nicotiana benthamiana |

| Metabolite Profiling | LC-MS grade solvents, analytical columns | Chromatographic separation and detection of metabolites |

| Gene Silencing | VIGS/RNAi constructs | Functional validation through gene knockdown in native hosts |

Functional Validation Protocols

Following candidate gene identification through omics approaches, several experimental protocols are essential for functional validation [23]:

Heterologous expression involves cloning candidate genes into suitable vectors (e.g., pET series) and expressing them in host systems such as Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or Nicotiana benthamiana [23]. The Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression in N. benthamiana has become particularly valuable for rapid co-expression of multiple metabolic genes with significantly less engineering effort compared to microbial systems [23].

In vitro enzyme assays test the catalytic function of purified recombinant proteins against predicted substrate analogs. These assays typically involve incubation of the enzyme with potential substrates followed by metabolite analysis using LC-MS/MS or NMR to detect reaction products [23].

Gene silencing techniques such as virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) or RNA interference (RNAi) confirm gene function in the native host organism by knocking down expression and monitoring resulting changes in metabolite profiles [23].

Genomics and transcriptomics have fundamentally transformed the field of natural product research, moving the discovery process from serendipitous finding to systematic, data-driven exploration. The integration of these omics technologies provides a powerful framework for elucidating complex biosynthetic pathways, revealing the extensive hidden metabolic potential within plants and microorganisms [23] [26]. As these technologies continue to evolve alongside advances in computational tools, machine learning, and data analytics, they promise to further accelerate the discovery of novel bioactive compounds with applications in medicine, agriculture, and industry [23] [24]. The future of natural product research lies in the continued refinement of these integrated omics approaches, enabling researchers to navigate the vast chemical diversity of nature with unprecedented precision and efficiency.

Core Methodologies and Applications: Engineering Living Discovery Platforms

Genetically encoded biosensors represent a transformative technology in metabolic engineering and natural product discovery. By coupling the detection of specific intracellular metabolites—such as the inhibitory products of biosynthetic pathways—directly to cellular survival, these tools enable high-throughput selection of optimized microbial factories. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of biosensor design principles, experimental methodologies, and applications within biosynthesis-guided natural product research. We detail the implementation of product inhibition-coupled survival systems that leverage metabolite-sensing transcription factors fused to fluorescent reporters and selection markers, allowing researchers to overcome critical bottlenecks in yield optimization and novel compound discovery. The integration of these approaches with emerging genome-mining strategies creates a powerful framework for unlocking the full potential of microbial natural products for drug development.

Natural products (NPs) and their derivatives represent a cornerstone of pharmaceutical development, with over 60% of chemotherapeutic agents originating from these compounds [30]. However, the discovery and optimization of NP production face significant challenges, including the silent nature of many biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in laboratory conditions and the complexity of measuring low-abundance metabolites in living systems. Genetically encoded biosensors have emerged as powerful tools to address these limitations by providing real-time, non-destructive monitoring of metabolic fluxes with high spatial and temporal resolution [31] [32].

The convergence of biosensor technology with natural product research has created new paradigms for biosynthesis-guided discovery. These approaches are particularly valuable for detecting "product inhibition," where the accumulation of pathway intermediates or final products limits overall yield—a common challenge in engineered microbial systems. By coupling biosensor detection to cellular survival through selectable markers, researchers can directly link metabolite production to host viability, creating powerful evolutionary pressure for strain improvement [33]. This review examines the fundamental principles, implementation strategies, and research applications of these coupled systems within the context of contemporary natural product discovery.

Biosensor Design Principles and Molecular Components

Core Architecture of Genetically Encoded Biosensors

Genetically encoded biosensors typically consist of two fundamental modules: a sensing domain and a reporting domain. The sensing module is often derived from natural transcription factors that undergo conformational changes upon binding specific small molecules. The reporting module typically consists of a fluorescent protein or enzyme that generates a quantifiable signal, allowing detection of the sensing event.

Sensing Mechanisms: Biosensors exploit various molecular mechanisms for metabolite detection. Transcription factor-based sensors utilize natural regulatory systems where metabolite binding alters DNA affinity, modulating transcription of reporter genes [33]. Allosteric transcription factors from bacterial systems are particularly valuable for their specificity and dynamic range. For example, the HgcR protein from Pseudomonas putida specifically binds d-2-hydroxyglutarate (d-2-HG) and activates transcription, serving as the foundation for the DHOR biosensor [33].

Reporter Systems: Common reporter modules include fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP, YFP, RFP) for optical detection and enzymatic reporters (e.g., luciferase, β-galactosidase) for amplified signals. Recent advances have employed circularly permuted fluorescent proteins (cpFP) that undergo conformational changes upon sensing, directly transducing metabolite concentration into fluorescence intensity [33].

Key Biosensor Classes for Metabolic Monitoring

Table 1: Major Genetically Encoded Biosensor Classes and Their Applications

| Biosensor Class | Detection Target | Mechanism | Dynamic Range | Applications in NP Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATeam [31] | ATP/ADP ratio | FRET between mseCFP and mVenus | ~150% | Monitoring cellular energy status during NP production |

| iATPSnFR [31] | ATP | cpSFGFP fluorescence turn-on | ~200% | Detecting ATP heterogeneity at single synapses |

| MaLions [31] | ATP | Split-FP complementation | 90-390% | Compartment-specific ATP monitoring |

| PercevalHR [31] | ATP/ADP ratio | cpYFP spectral shift | ~500% | Real-time energy charge measurements |

| DHOR [33] | d-2-hydroxyglutarate | HgcR-cpYFP conformational change | >1700% | Point-of-care testing & live-cell d-2-HG detection |

Table 2: Technical Specifications of Representative Metabolic Biosensors

| Biosensor | Sensing Domain | Reporting Domain | Kd/EC50 | pH Sensitivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATeam1.03YEMK | ε-subunit of F0F1-ATP synthase | FRET (mseCFP/mVenus) | 3.3 mM | Moderate | [31] |

| iATPSnFR | ε-subunit of F0F1-ATP synthase | cpSFGFP | 50-120 μM | Sensitive | [31] |

| MaLionG | ε-subunit of F0F1-ATP synthase | Split-citrine | 1.1 mM | Sensitive to low pH | [31] |

| DHOR | HgcR transcription factor | cpYFP | Not specified | Not specified | [33] |

Coupling Mechanisms: From Product Detection to Cell Survival

Fundamental Coupling Strategy

The core innovation in survival-coupled biosensor systems lies in connecting metabolite detection to essential gene expression. This is typically achieved by placing a selectable marker—such as an antibiotic resistance gene or essential metabolic enzyme—under the control of a biosensor-responsive promoter. When the target metabolite (e.g., a natural product) reaches a threshold concentration, it triggers expression of the survival gene, allowing only high-producing cells to proliferate under selective conditions.

Molecular Implementation Approaches

Transcription Factor-Based Selection: This approach utilizes natural transcription factors that regulate essential genes in response to metabolite binding. The native regulatory system is engineered so that the transcription factor controls a heterologous essential gene, creating dependence on the target metabolite.

Hybrid Promoter Systems: Synthetic promoters containing transcription factor binding sites control expression of selection markers. These systems can be tuned by modifying operator sequences, promoter strength, and ribosome binding sites to adjust the selection threshold.

Two-Component System Integration: Some implementations incorporate bacterial two-component systems where a sensor kinase detects the metabolite and phosphorylates a response regulator, which then activates survival gene expression.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Biosensor Engineering and Characterization

Protocol 1: Biosensor Construction from Native Transcription Factors

Transcription Factor Identification: Mine microbial genomes for regulators associated with natural product pathways or metabolite-responsive systems [1]. HgcR was identified through analysis of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 D2HGDH genes [33].

Sensing Domain Isolation: Amplify the coding sequence of the ligand-binding domain using high-fidelity PCR with incorporation of appropriate restriction sites.

Vector Assembly: Clone the sensing domain into a modular biosensor scaffold vector containing a cpFP reporter using Golden Gate or Gibson assembly.

Initial Characterization: Transform the construct into a model host (e.g., E. coli) and measure fluorescence response to metabolite supplementation using plate readers or flow cytometry.

Affinity Maturation: For suboptimal sensors, employ directed evolution through error-prone PCR or DNA shuffling to improve dynamic range, specificity, or affinity.

Protocol 2: Coupling to Survival Systems

Selection Marker Choice: Identify an appropriate selection marker based on the host system (e.g., antibiotic resistance, essential metabolic gene complementation).

Promoter Engineering: Replace the native promoter of the selection marker with the biosensor-responsive promoter element.

Threshold Tuning: Modulate system sensitivity by:

- Varying operator copy number

- Adjusting ribosome binding site strength

- Incorporating translational fusions

- Adding regulatory RNA elements

System Validation: Test the coupled system under selective conditions with varying metabolite concentrations to establish the correlation between production and survival.

Implementation in Natural Product Discovery

Protocol 3: High-Throughput Strain Selection

Library Generation: Create genetic diversity through random mutagenesis, CRISPR-based editing, or homologous recombination of pathway genes.

Selection Pressure Application: Culture the library under conditions where the survival gene is essential (e.g., antibiotic-containing media for resistance markers).

Enrichment Cycles: Perform multiple rounds of growth and dilution to progressively enrich for high-producing variants.

Single-Cell Isolation: Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate individual clones based on biosensor signal intensity.

Validation: Characterize selected strains for product yield using analytical methods (LC-MS, HPLC) to correlate biosensor signal with actual production.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Implementation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolite Biosensors | ATeam, iATPSnFR, MaLions, PercevalHR, DHOR | Real-time monitoring of metabolic fluxes | Vary in affinity, dynamic range, and pH sensitivity [31] |

| Reporter Proteins | cpYFP, cpSFGFP, mVenus, mRuby3 | Signal generation via fluorescence changes | cpFPs offer intensity-based sensing; FRET pairs enable rationetric measurements [33] |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance genes, essential gene complementation | Coupling product detection to cellular survival | Choice depends on host system and selection stringency required |

| Expression Vectors | Modular cloning systems, chromosomal integration vectors | Biosensor delivery and maintenance | Consider copy number, stability, and compatibility with production hosts |

| Genome Mining Tools | antiSMASH, PRISM, BAGEL | Identification of BGCs and potential sensing elements | Essential for discovering native regulatory systems [1] |

Applications in Natural Product Research and Drug Discovery

Overcoming Product Inhibition in Engineered Pathways

Product inhibition represents a major bottleneck in microbial natural product synthesis, where accumulation of pathway intermediates or final products suppresses further production. Survival-coupled biosensors directly address this challenge by selecting variants that maintain flux through inhibited steps. For example, in polyketide and nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis, thioesterase domains often show product inhibition; biosensors detecting final products can select for mutant thioesterases with reduced inhibition.

Activation of Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

Most BGCs in microbial genomes remain silent under laboratory conditions. Biosensor-coupled survival systems enable direct selection for activating mutations or regulatory elements that trigger expression of these silent clusters. This approach has been successfully applied to discover novel natural products from actinomycetes and cyanobacteria by using product-sensing biosensors to detect antibiotic activity or specific chemical scaffolds.

Dynamic Pathway Optimization

Traditional metabolic engineering often employs constitutive overexpression, which may create imbalances and accumulation of inhibitory intermediates. Biosensor-regulated pathways automatically adjust enzyme expression levels in response to metabolite concentrations, preventing bottleneck formation. This dynamic control has been demonstrated in terpenoid and alkaloid pathways where intermediate toxicity limits production.

Integration with Advanced Analytics

The combination of biosensor-based selection with machine learning (ML) approaches creates powerful platforms for strain optimization. ML algorithms can analyze high-dimensional data from biosensor outputs to predict optimal genetic modifications, effectively closing the design-build-test-learn cycle [34]. This integration is particularly valuable for complex natural product pathways with poorly understood regulation.

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

Genetically encoded biosensors coupled to survival systems represent a rapidly advancing technology with transformative potential for natural product discovery and development. Future directions will likely focus on expanding the biosensor toolbox to cover a wider range of chemical scaffolds, improving the dynamic range and orthogonality of sensing systems, and developing more precise coupling mechanisms that allow graded selection based on production levels.