Unlocking Azetidine Biosynthesis: The Catalytic Power of Non-Haem Iron Enzymes in Drug Discovery

This article explores the recent groundbreaking discovery of a novel biosynthetic pathway for azetidine-containing amino acids, a class of compounds with significant pharmaceutical potential.

Unlocking Azetidine Biosynthesis: The Catalytic Power of Non-Haem Iron Enzymes in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the recent groundbreaking discovery of a novel biosynthetic pathway for azetidine-containing amino acids, a class of compounds with significant pharmaceutical potential. We delve into the mechanism by which non-haem iron-dependent enzymes, specifically PolF from the HDO superfamily and its helper PolE, catalyze the formation of the highly strained azetidine ring from linear amino acid precursors like L-isoleucine. Covering foundational concepts, methodological approaches, and troubleshooting strategies, this resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive understanding of this enzymatic process. The content also validates this pathway against known mechanisms and discusses its broader implications for the efficient synthesis of bioactive molecules and the development of new antifungal agents.

The Azetidine Enigma: From Bioactive Motif to Biosynthetic Breakthrough

Azetidines, four-membered saturated nitrogen-containing heterocycles, are increasingly significant scaffolds in medicinal chemistry and organic synthesis. Their importance stems from a combination of unique structural properties, substantial ring strain, and presence in bioactive molecules. This guide provides a technical overview of azetidine characteristics, explores a novel biosynthetic pathway relevant to azetidine amino acid production, and details contemporary synthetic methodologies.

Core Structural Properties and Significance in Drug Discovery

The azetidine ring is a cyclobutane derivative where one carbon atom is replaced by nitrogen. This substitution creates a polar, strained heterocycle with distinct physicochemical properties.

Ring Strain and Conformation: The bond angles within the azetidine ring are constrained to approximately 90°, a significant deviation from the ideal tetrahedral geometry of sp³-hybridized atoms (109.5°). This distortion results in a ring strain energy of about 105 kJ molâ»Â¹ [1]. This strain is a primary driver of azetidine reactivity, facilitating ring-opening and ring-expansion reactions. The ring adopts a "wing-shaped" conformation, and the introduction of substituents can significantly influence its overall geometry and steric profile [2].

Physicochemical Advantages: Incorporating azetidines into bioactive molecules is a established strategy for improving drug-like properties. Azetidines can increase molecular rigidity, which reduces the entropic penalty upon binding to a biological target. They often improve aqueous solubility and enhance metabolic stability by blocking sites of oxidative metabolism. Furthermore, as saturated rings, they help increase the fraction of Csp³ character (Fsp³) in a molecule, a parameter associated with higher clinical success rates in drug development [3].

Presence in Bioactive Molecules: Azetidine is a key pharmacophore in several approved drugs and clinical candidates. Notable examples include:

- Cobimetinib: A mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitor used in oncology [4].

- Azelnidipine: A dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker used as an antihypertensive agent [4] [2].

- Baricitinib: A Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor used for autoimmune diseases [2].

- Ximelagatran: An oral direct thrombin inhibitor [4].

A Novel Biosynthetic Pathway for Azetidine Amino Acids

While traditional chemical synthesis of azetidines is challenging, nature has evolved enzymatic pathways to construct this strained ring. Recent groundbreaking research has elucidated a novel biosynthetic route to azetidine-containing amino acids in the polyoxin antifungal pathway, mediated by non-haem iron-dependent enzymes [5] [6] [7].

Experimental Protocol: Elucidating the PolF and PolE Pathway

The following methodology outlines the key experiments used to characterize this biosynthesis.

Gene Knockout and Metabolite Analysis: The genes encoding putative biosynthetic enzymes PolE and PolF were individually disrupted in the polyoxin producer Streptomyces cacaoi via in-frame deletion [5].

- Analysis: The resulting mutant strains were cultured under polyoxin-producing conditions. The fermentation broth was analyzed using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS). The polF mutant did not produce any measurable polyoxin A (<1% of wild-type), demonstrating its essential role. The polE mutant produced a reduced amount (~10% of wild-type), indicating its auxiliary function [5].

Enzyme Expression and Purification: The polF gene was expressed in E. coli, and the resulting protein was purified. The enzyme was initially isolated in an apo (metal-free) form [5].

In Vitro Reconstitution of Activity:

- Metallation: Apo-PolF was incubated with an excess of Fe(II) under anaerobic conditions. Unbound iron was removed via a desalting column, resulting in Fe-reconstituted PolF [5].

- Assay Conditions: Enzyme assays were performed by incubating PolF with L-isoleucine (L-Ile) or L-valine (L-Val) under anaerobic conditions. Reactions were initiated by adding an Oâ‚‚-saturated buffer. The dependence on Oâ‚‚ and Fe(II) was confirmed through control experiments omitting each component [5].

- Product Analysis: Reaction products were derivatized with dansyl chloride (DnsCl) and analyzed by LC-MS. The azetidine product from L-Ile was identified as polyoximic acid (PA) by comparison with an authentic standard. The product from L-Val was identified as 3-methyl-ene-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (MAA) through NMR characterization [5].

Mechanistic Probing via Intermediate Trapping: Assays with L-Val under single-turnover conditions (using 2 equivalents of Fe(II) and no external reductant) allowed for the detection and quantification of reaction intermediates, including 3,4-dehydrovaline (3,4-dh-Val) and 3-dimethylaziridine-2-carboxylic acid (Azi) [5].

Biosynthetic Mechanism and Pathway Logic

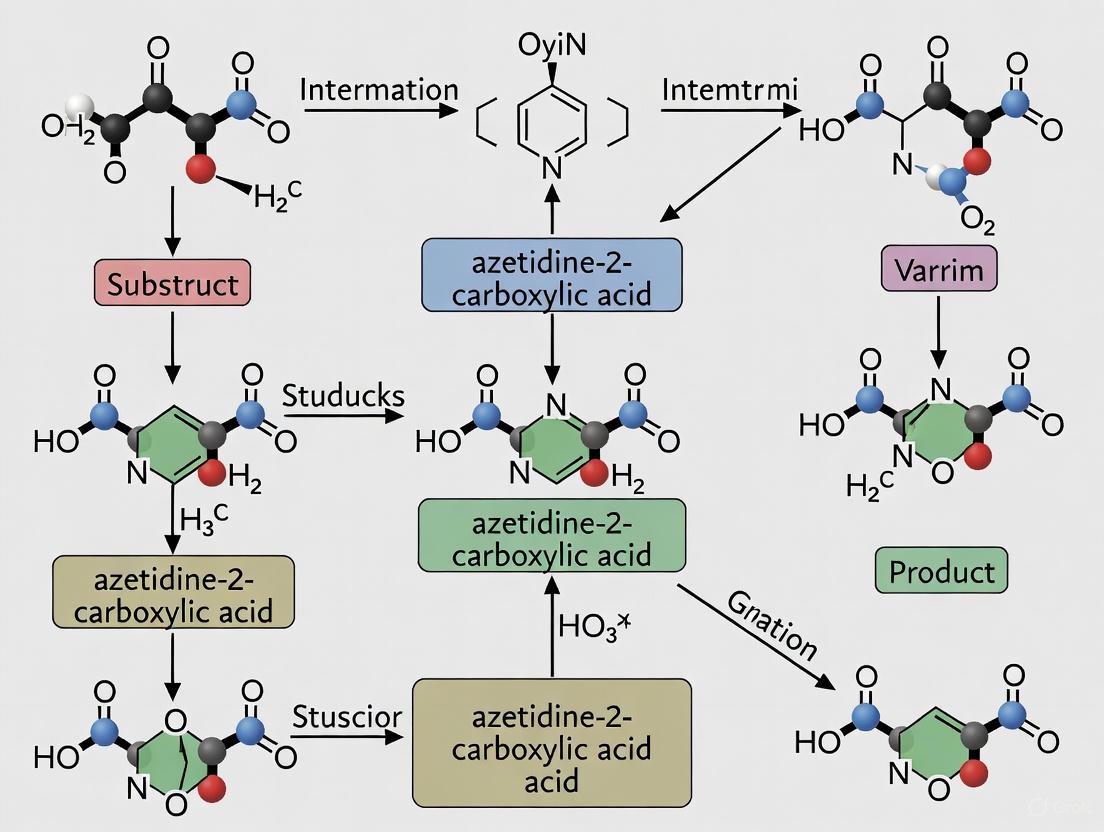

The biosynthesis of polyoximic acid from L-Ile is a two-step enzymatic process. The following diagram illustrates the roles of PolE and PolF in this pathway.

Role of PolE: PolE is an Fe and pterin-dependent oxidase that catalyzes the desaturation of L-Ile to form a 3,4-dehydroisoleucine intermediate. This step increases the flux through the pathway but is not strictly essential, as PolF can process the native amino acid directly at a lower efficiency [5] [7].

Role of PolF: PolF is the key enzyme responsible for azetidine ring formation. It belongs to the haem-oxygenase-like dimetal oxidase and/or oxygenase (HDO) superfamily. It utilizes a diiron (Feâ‚‚) core to activate molecular oxygen [5] [7].

- Mechanism: The current model suggests PolF generates a μ-peroxo-Fe(III)₂ intermediate capable of cleaving an unactivated C–H bond. The subsequent transformations, including the crucial intramolecular C–N bond formation to close the four-membered ring, are proposed to proceed through radical mechanisms [5]. The enzyme can catalyze multiple reactions on a single substrate—desaturation, hydroxylation, and C–N bond formation—with the azetidine-forming pathway being dominant for L-Ile and L-Val [5].

Quantitative Profile of PolF Substrate Specificity

The substrate specificity of PolF was experimentally determined, revealing its preference for medium-chain aliphatic amino acids. The table below summarizes the products formed from various substrates.

Table 1: Substrate Specificity and Product Profile of PolF Enzyme

| Substrate | Primary Product(s) | Product Type | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Isoleucine | Polyoximic Acid | Azetidine | Native biosynthetic substrate [5] |

| L-Valine | 3-Methylene-azetidine-2-carboxylic Acid | Azetidine | Efficient conversion to azetidine [5] |

| L-Leucine | Hydroxylation (major), Desaturation (minor) | Non-cyclic | No azetidine formed [5] |

| L-Methionine | Hydroxylation (major), Desaturation (minor) | Non-cyclic | No azetidine formed [5] |

| L-allo-Ile, D-Ile, D-allo-Ile | Azetidine | Azetidine | Small but detectable amounts; stereochemistry not absolute [5] |

Modern Synthetic Approaches to Azetidines

Beyond biosynthesis, organic chemists have developed innovative synthetic strategies to access diverse azetidine scaffolds. Three contemporary methods are highlighted below.

Intermolecular Aza Paternò-Büchi Reaction

This photochemical [2+2] cycloaddition between imines and alkenes is a direct and modular approach. A recent breakthrough uses N-sulfamoyl fluoride-substituted imines, which, upon triplet energy transfer catalysis, generate reactive intermediates that couple with a wide range of alkenes to form azetidines in high yields [3]. The N-SFâ‚‚ group is a valuable handle for further functionalization or removal.

Strain-Release Difunctionalization of Azabicyclo[1.1.0]butanes (ABBs)

Highly strained ABBs serve as versatile precursors to 1,3-disubstituted azetidines. Under photoredox catalysis, these spring-loaded scaffolds undergo ring-opening difunctionalization. For example, using a bench-stable SFâ‚…-transfer reagent, ABBs can be converted to N-SFâ‚… azetidines, a novel class of potential bioisosteres with high aqueous stability and increased lipophilicity [8].

Enantioselective Difunctionalization of Azetines

A powerful catalytic method provides access to chiral 2,3-disubstituted azetidines. Using a Cu/bisphosphine catalyst system, azetines undergo asymmetric borylallylation, installing two versatile functional groups with concomitant creation of two stereogenic centers in a single step with excellent regio-, enantio-, and diastereocontrol [9]. The boryl and allyl groups can be further transformed, enabling rapid diversification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Azetidine Biosynthesis and Synthesis Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Fe(II) Salts (e.g., FeSOâ‚„) | Cofactor for non-haem iron enzymes (PolE, PolF) [5]. | In vitro enzymatic assays |

| Bâ‚‚pinâ‚‚ (Bis(pinacolato)diboron) | Boron source for enantioselective borylallylation reactions [9]. | Synthetic chemistry: Cu-catalyzed difunctionalization |

| ABB Precursors (Azabicyclo[1.1.0]butanes) | Spring-loaded intermediates for strain-release synthesis [8]. | Synthetic chemistry: Photocatalytic synthesis of N-SFâ‚… azetidines |

| SFâ‚… Transfer Reagents (Bench-stable) | Source of SFâ‚… radical for pentafluorosulfanylation [8]. | Synthetic chemistry: Radical difunctionalization of ABBs |

| Sulfamoyl Fluoride Imines | Substrates for generating reactive triplet imine intermediates [3]. | Synthetic chemistry: Aza Paternò-Büchi reaction |

| Chiral Bisphosphine Ligands (e.g., Ph-BPE) | Control enantioselectivity in metal-catalyzed reactions [9]. | Synthetic chemistry: Asymmetric synthesis of azetidines |

| Photocatalysts (e.g., 2,7-Brâ‚‚-TXT) | Mediate energy or electron transfer under light irradiation [3] [8]. | Synthetic chemistry: Photochemical cyclizations and radical reactions |

| Fmoc-D-Pro-OH | Fmoc-D-Pro-OH, CAS:101555-62-8, MF:C20H19NO4, MW:337.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fmoc-1-Nal-OH | Fmoc-1-Nal-OH, CAS:96402-49-2, MF:C28H23NO4, MW:437.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Azetidine, a saturated four-membered ring containing one nitrogen atom, is a structure of significant interest in medicinal chemistry due to its substantial ring strain (approximately 25.4 kcal molâ»Â¹) and presence in numerous bioactive compounds [5] [10]. This high-energy configuration imparts unique reactivity and conformational properties that make it valuable for drug design, particularly in the development of antimicrobial agents [7]. Despite its pharmaceutical importance, the biosynthetic origins of azetidine-containing natural products have remained largely enigmatic until recent investigations elucidated novel enzymatic pathways [5] [6].

The antifungal nucleoside polyoxin A contains a distinctive azetidine amino acid known as polyoximic acid (PA) [5] [10]. Early isotope-labeling studies indicated that PA originates from l-isoleucine (l-Ile), suggesting a previously uncharacterized biosynthetic mechanism distinct from known pathways [10]. Two previously unidentified enzymes, PolE and PolF, encoded within the polyoxin biosynthetic gene cluster, have now been identified as the key catalysts responsible for azetidine ring formation [5]. This review comprehensively examines the mechanistic details of this recently discovered biosynthetic pathway, with particular emphasis on the novel non-haem iron-dependent enzymes that construct this strained heterocycle.

Biosynthetic Pathways to Azetidine Rings

Previously Characterized Pathways

Before the elucidation of the polyoxin pathway, two primary enzymatic mechanisms were known to generate azetidine rings in natural products:

S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM)-dependent enzymes: These catalysts promote an intramolecular nucleophilic cyclization of SAM, yielding azetidine carboxylic acid and 5'-methylthioadenosine [5] [10]. This pathway represents a well-established route to azetidine-containing amino acids.

α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) and Fe-dependent oxygenases: Exemplified by the okaramine biosynthetic pathway, these enzymes facilitate radical-mediated oxidative C–C bond formation to generate the azetidine ring [5] [10]. This mechanism expands the repertoire of radical enzymes in natural product biosynthesis.

Both these established routes share a common limitation: their dependence on metabolically expensive precursors (SAM or α-KG), which restricts their utility for biocatalytic applications [5] [10].

The Polyoxin Azetidine Biosynthetic Pathway

The biosynthesis of polyoximic acid in the antifungal polyoxin pathway represents a distinct mechanistic paradigm. Gene knockout experiments in Streptomyces cacaoi demonstrated that PolF is absolutely essential for polyoxin A production (<1% of wild-type levels), while PolE disruption resulted in substantially reduced titers (~10% of wild-type) [5] [10]. This genetic evidence established PolF as the central catalyst in azetidine formation, with PolF playing an auxiliary role in enhancing pathway efficiency.

Table 1: Key Enzymes in Azetidine Amino Acid Biosynthesis

| Enzyme | Family | Cofactor Requirement | Catalytic Function | Essentiality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PolF | Heme-oxygenase-like dimetal oxidase/oxygenase (HDO) | Diiron center (Feâ‚‚) | Transforms l-Ile and l-Val to azetidine derivatives via desaturated intermediate | Essential (<1% product without PolF) |

| PolE | DUF6421 | Fe and pterin | Catalyzes desaturation of l-Ile, increasing pathway flux | Non-essential but increases titer (~10% product without PolE) |

Enzymatic Mechanisms of Azetidine Formation

PolF: A Novel HDO Enzyme Catalyzing Azetidine Ring Formation

PolF represents a newly discovered member of the heme-oxygenase-like dimetal oxidase and/or oxygenase (HDO) superfamily, an emerging class of diiron-dependent enzymes that activate Oâ‚‚ for diverse oxidative transformations [5] [10]. Structural homology analysis using Foldseek revealed that PolF shares structural features with characterized HDO enzymes, despite lacking significant sequence similarity [5]. Notably, PolF expands the catalytic repertoire of HDO enzymes, as no previously characterized family member was known to construct azetidine rings.

Biochemical characterization demonstrated that PolF is sufficient to convert l-Ile to polyoximic acid in vitro when reconstituted with Fe(II) under aerobic conditions [5]. The enzyme exhibits a strict metal requirement, with activity observed only with Fe(II) among tested transition metals [5]. Activity dependence on external reductants such as ascorbate or dithiothreitol aligns with the established need for reducing equivalents during multiple catalytic turnovers of HDO enzymes [5] [10].

Table 2: Substrate Specificity of PolF

| Substrate | Major Product(s) | Structural Requirement | Proposed Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| l-Isoleucine | Polyoximic acid (azetidine) | β-Methyl group | Steric and electronic stabilization of radical intermediate |

| l-Valine | 3-methylene-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (MAA) | β-Methyl group | Similar branching to l-Ile at β-position |

| l-Leucine | Hydroxylation products (minor desaturation) | Lack of β-methyl group | Altered radical migration pathway |

| l-Methionine | Hydroxylation products (minor desaturation) | Sulfur-containing side chain | Competing reaction pathways |

| Other proteogenic amino acids | No detectable products | - | Specific active site constraints |

Mechanistic Insights into PolF Catalysis

Detailed investigation of PolF catalysis using l-valine as a substrate revealed a complex reaction mechanism involving multiple intermediates [5]. Under single-turnover conditions, the following species were detected, indicating a branched catalytic pathway:

- 3,4-dehydrovaline (3,4-dh-Val): The major initial product, characterized by a -2 Da mass shift corresponding to desaturation.

- 3-dimethylaziridine-2-carboxylic acid (Azi): A three-membered ring intermediate demonstrating PolF's capacity for C–N bond formation.

- 4-hydroxyvaline and 3-hydroxyvaline: Hydroxylation products representing alternative oxidative outcomes.

The conversion of 3,4-dh-Val to the azetidine product MAA under both enzymatic and chemical conditions suggests that the desaturated intermediate can undergo non-enzymatic cyclization, though the enzymatic pathway significantly accelerates this process [5].

Spectroscopic and structural studies indicate that PolF employs a μ-peroxo-Fe(III)â‚‚ species to initiate catalysis by cleaving an unactivated C–H bond with a bond dissociation energy up to 101 kcal molâ»Â¹ [5] [10]. This potent oxidant abstracts a hydrogen atom from the substrate, generating a carbon-centered radical that subsequently participates in C–N bond formation through radical mechanisms [5]. Crystal structures of PolF in complex with l-Ile reveal precise substrate positioning that orients the reactive centers for selective azetidine formation over alternative oxidative outcomes.

The following diagram illustrates the proposed catalytic cycle of PolF:

PolE: A Supplementary Enzyme Enhancing Biosynthetic Flux

PolE, a member of the DUF6421 family, functions as an Fe- and pterin-dependent oxidase that catalyzes the desaturation of l-Ile to 3,4-dehydroisoleucine [5] [10]. This activity positions PolE as an auxiliary enzyme that increases the local concentration of the desaturated intermediate, thereby enhancing the flux through the azetidine biosynthetic pathway. The coordinated action of PolE and PolF represents an efficient metabolic strategy for producing the strained azetidine ring system.

Experimental Characterization of Azetidine Biosynthesis

Gene Knockout and Microbial Fermentation

Protocol: Gene Disruption in Streptomyces cacaoi

- Strain Preparation: Culture wild-type S. cacaoi under polyoxin-producing conditions.

- Gene Deletion: Perform in-frame deletion of polE and polF genes using standard genetic techniques.

- Fermentation: Culture wild-type and mutant strains under identical polyoxin-producing conditions.

- Metabolite Extraction: Harvest fermentation broth and extract metabolites using appropriate solvents.

- LC-MS Analysis: Analyze polyoxin A production using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry with multiple reaction monitoring.

- Quantification: Compare peak areas of polyoxin A in mutants versus wild-type strains.

This genetic approach established that PolF is absolutely essential for polyoxin biosynthesis, while PolE significantly enhances production yield [5] [10].

In Vitro Enzyme Assays

Protocol: PolF Activity Assay

- Enzyme Preparation: Express and purify PolF from E. coli in predominantly apo form.

- Metallation: Incubate apo-PolF with 3 equivalents of Fe(II) under anaerobic conditions in an inert atmosphere chamber.

- Excess Metal Removal: Remove unbound Fe(II) using a desalting column.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare enzyme-substrate mixture anaerobically with l-Ile or l-Val as substrate.

- Reaction Initiation: Inject Oâ‚‚-saturated buffer to initiate the oxidative reaction.

- Product Derivatization: Treat reaction products with dansyl chloride (DnsCl) for enhanced detection.

- Analysis: Identify and quantify products using LC-MS with comparison to authentic standards.

Critical controls include reactions without Fe(II), without Oâ‚‚, and with heat-inactivated enzyme, all of which should show no product formation [5].

Intermediate Trapping and Characterization

Protocol: Single-Turnover Experiments

- Enzyme Preparation: Reconstitute PolF with precisely 2 equivalents of Fe(II).

- Reaction Setup: Combine enzyme and substrate under anaerobic conditions without external reductant.

- Rapid Mixing: Expose to Oâ‚‚ for defined time intervals.

- Reaction Quenching: Acidify or flash-freeze to terminate reactions at specific timepoints.

- Intermediate Identification: Analyze timepoints by LC-MS to detect transient intermediates.

- Kinetic Analysis: Determine relative rates of formation for different intermediates.

This approach identified 3,4-dh-Val as the major initial product, followed by Azi, 4-OH-Val, and 3-OH-Val, providing critical insights into the branched reaction mechanism [5].

The following workflow summarizes the key experimental approaches for characterizing azetidine biosynthesis:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Azetidine Biosynthesis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Sources | Recombinant PolF and PolE expressed in E. coli | Catalytic core of azetidine formation; study structure-function relationships |

| Metal Cofactors | Fe(II) salts (e.g., FeSOâ‚„) | Essential cofactor for both PolF and PolE; reconstitutes active enzymes |

| Substrates | l-Isoleucine, l-Valine, l-allo-Isoleucine | Natural substrates for azetidine formation; study substrate specificity |

| Analytical Standards | Polyoximic acid (from polyoxin A hydrolysis), 3,4-dehydrovaline | Reference compounds for product identification and quantification |

| Derivatization Reagents | Dansyl chloride (DnsCl) | Enhances detection sensitivity of amino acid products in LC-MS |

| Reducing Agents | Ascorbate, dithiothreitol (DTT) | Maintains Fe in reduced state during multiple turnover experiments |

| Chromatography | Reverse-phase LC columns, mobile phases | Separation and analysis of substrates, intermediates, and products |

Implications and Future Perspectives

The discovery of PolF and PolE as the catalysts for azetidine amino acid biosynthesis represents a significant advancement in natural product biochemistry. This pathway demonstrates nature's ingenuity in employing radical chemistry to construct strained ring systems that challenge conventional synthetic approaches. The identification of PolF as a novel HDO enzyme expands the functional diversity of this emerging superfamily and provides new insights into diiron-mediated C–H activation [5] [10].

From a pharmaceutical perspective, understanding this biosynthetic route enables potential bioengineering approaches to produce azetidine-containing compounds with enhanced properties. The azetidine ring's capacity to modulate molecular rigidity, improve metabolic stability, and enhance target binding affinity makes it particularly valuable in drug design [7]. The enzymatic machinery revealed in this pathway offers potential biocatalytic tools for sustainable synthesis of these valuable motifs under mild conditions, contrasting with traditional chemical methods that often require harsh reagents and elevated temperatures [7].

Future research directions include detailed structural characterization of the enzyme-substrate complexes, exploration of the enzyme's engineering potential for producing azetidine derivatives, and investigation of whether similar mechanisms operate in other azetidine-containing natural products. The interplay between PolE and PolF also presents an interesting model for studying metabolic channeling and pathway optimization in natural product biosynthesis.

The azetidine ring, a four-membered nitrogen-containing saturated heterocycle, is a crucial structural motif in numerous bioactive compounds and pharmaceuticals [5] [10]. Its high ring strain of approximately 25.4 kcal molâ»Â¹ makes it a valuable substrate for various chemical transformations, including ring opening, expansion, and metal-catalyzed reactions [5] [10]. Despite its significance, the enzymatic pathways responsible for azetidine biosynthesis have remained largely enigmatic, creating a major bottleneck in understanding natural product biosynthesis and developing biocatalytic applications [5] [10] [11].

Historically, researchers have identified only a limited number of enzymatic mechanisms capable of forming this strained ring system. The two principal known pathways—S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-dependent cyclization and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)/Fe-dependent oxygenase catalysis—have significant biochemical and practical limitations that restrict their utility in drug discovery and bioengineering [5] [10] [11]. These pathways require metabolically expensive precursors, exhibit limited substrate scope, and offer minimal flexibility for synthetic biology applications.

This review comprehensively analyzes the historical constraints of established azetidine biosynthetic pathways, providing a detailed examination of their mechanistic limitations and biochemical requirements. Furthermore, we contextualize these limitations within the recent groundbreaking discovery of a new biosynthetic route mediated by non-haem iron-dependent enzymes PolE and PolF in the polyoxin antifungal pathway [5] [10] [11]. By framing this new pathway as a solution to longstanding challenges, this review provides researchers with a comprehensive understanding of the evolving landscape of azetidine biosynthesis.

Established Azetidine Biosynthetic Pathways and Their Constraints

SAM-Dependent Azetidine Formation

The best-characterized mechanism for azetidine ring formation involves S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-dependent enzymes that catalyze an intramolecular nucleophilic cyclization [5] [10]. In this pathway, SAM serves as both the substrate and cofactor, undergoing an internal cyclization to yield azetidine carboxylic acid and 5'-methylthioadenosine (MTA) as a byproduct [10].

Table 1: Limitations of SAM-Dependent Azetidine Biosynthesis

| Limitation Factor | Biochemical Impact | Practical Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolically Expensive Precursor | Requires SAM, consuming ATP equivalents | Energetically costly for microbial production systems |

| Fixed Product Structure | Produces only azetidine-2-carboxylic acid | Limited chemical diversity for drug discovery |

| Byproduct Accumulation | Generates 5'-methylthioadenosine (MTA) | Potential feedback inhibition and metabolic burden |

| Limited Substrate Scope | Restricted to SAM or close analogs | Difficult to generate azetidine derivatives with side-chain variations |

The SAM-dependent pathway presents substantial metabolic challenges for industrial or biocatalytic applications. The requirement for SAM, an expensive nucleotide derivative, increases the metabolic burden on production hosts [5]. Furthermore, the structural limitation of producing exclusively azetidine-2-carboxylic acid constrains its utility for generating diverse azetidine-containing compounds with varied pharmaceutical properties [5] [10].

α-Ketoglutarate and Fe-Dependent Oxygenase Pathway

An alternative azetidine formation mechanism occurs in the biosynthesis of okaramine, where an α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) and Fe-dependent oxygenase catalyzes a radical-mediated oxidative C–C bond formation to produce the azetidine ring [5] [10] [11]. This pathway represents a distinct biochemical strategy that diverges from the SAM-dependent cyclization mechanism.

Table 2: Limitations of α-KG/Fe-Dependent Azetidine Biosynthesis

| Limitation Factor | Biochemical Impact | Practical Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Cofactor Requirement | Needs α-ketoglutarate as essential cosubstrate | Increased metabolic cost and complexity |

| Stoichiometric Byproduct | Forms succinate and COâ‚‚ for each reaction cycle | Potential metabolic imbalance in production hosts |

| Radical Intermediate Control | Requires precise radical stabilization | Limited enzyme engineering potential |

| Substrate Specificity | Highly specific to native biosynthetic context | Difficult to repurpose for novel compound production |

The α-KG-dependent pathway, while mechanistically distinct from the SAM-dependent route, shares similar practical limitations [5]. The requirement for α-ketoglutarate as an essential cosubstrate adds significant metabolic cost, while the production of stoichiometric byproducts (succinate and CO₂) complicates bioprocess optimization [5] [11]. Additionally, the need for precise control of radical intermediates limits engineering possibilities for creating modified azetidine structures.

Experimental Characterization of Azetidine Biosynthesis

Gene Inactivation Studies

Critical insights into azetidine biosynthesis emerged from targeted gene knockout experiments in the polyoxin producer Streptomyces cacaoi [5] [10]. Researchers performed in-frame deletion of polE and polF genes, then cultured the mutants under polyoxin-producing conditions. The fermentation broth was analyzed using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to quantify polyoxin production [5] [10].

Protocol: Gene Knockout and Metabolite Analysis

- In-frame gene deletion: Precisely delete polE and polF genes from S. cacaoi genome (Supplementary Fig. 1 [5])

- Fermentation culture: Grow wild-type and mutant strains under polyoxin-producing conditions

- Metabolite extraction: Process fermentation broth for LC-MS analysis

- LC-MS analysis: Quantify polyoxin A production using validated methods

- Data interpretation: Compare metabolite profiles between strains

The gene inactivation results demonstrated that PolF is absolutely essential for polyoximic acid biosynthesis, with the polF mutant producing less than 1% of wild-type polyoxin A levels [5] [10]. In contrast, the polE mutant produced approximately 10% of wild-type levels, indicating a supplementary rather than essential role for PolE [5] [10]. These findings established PolF as the core enzymatic component responsible for azetidine formation.

Enzyme Expression and Purification

To biochemically characterize PolF, researchers expressed and purified the enzyme from E. coli (Supplementary Fig. 3 [5] [10]). The initial purification yielded predominantly apo-PolF, consistent with the weak iron affinity reported for haem-oxygenase-like dimetal oxidase and/or oxygenase (HDO) superfamily enzymes in the absence of substrate [5] [10].

Protocol: PolF Reconstitution and Activity Assay

- Enzyme purification: Express PolF in E. coli and purify using affinity chromatography

- Iron reconstitution: Incubate apo-PolF with 3 equivalents of Fe(II) under anaerobic conditions

- Excess iron removal: Use desalting column to remove unbound Fe(II)

- Iron quantification: Measure iron content (typically ~1.5 eq. per PolF) [5] [10]

- Anaerobic assay preparation: Mix enzyme and substrate in oxygen-free environment

- Reaction initiation: Add Oâ‚‚-saturated buffer to start reaction

- Product derivatization: Treat reaction products with dansyl chloride (DnsCl)

- Product analysis: Analyze derivatized products by LC-MS (Supplementary Figs. 4-6 [5])

Activity assays demonstrated that PolF exclusively catalyzes the transformation of L-isoleucine to polyoximic acid when reconstituted with Fe(II) and oxygen [5] [10]. Control reactions lacking Fe(II), Oâ‚‚, or containing heat-inactivated PolF showed no product formation, confirming the enzyme's dependence on both iron and oxygen [5].

Substrate Specificity Profiling

Comprehensive substrate specificity studies revealed that PolF reacts selectively with medium-size aliphatic amino acids [5] [10]. When tested against the 20 proteogenic amino acids, PolF showed significant activity toward L-valine, producing 3-methylene-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (MAA) as a -4 Da modified product (Supplementary Fig. 9 [5] [10]). L-leucine and L-methionine yielded primarily hydroxylation products with minor desaturation products, while other amino acids produced no detectable products [5] [10].

Table 3: PolF Substrate Specificity and Products

| Substrate | Major Product(s) | Structural Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| L-isoleucine | Polyoximic acid (PA) | β-methyl group critical |

| L-valine | 3-methylene-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (MAA) | Medium-size aliphatic chain |

| L-leucine | Hydroxylation products (minor desaturation) | Branched chain but no azetidine |

| L-methionine | Hydroxylation products (minor desaturation) | Sulfur-containing but no azetidine |

| Other proteogenic amino acids | No detectable products | Specificity for aliphatic substrates |

Stereochemical studies using L-isoleucine stereoisomers revealed that while L-allo-Ile, D-Ile, and D-allo-Ile all yielded small amounts of azetidine products, the stereochemistries at C2 and C3 positions significantly influence catalytic efficiency [5] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Azetidine Biosynthesis Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Apo-PolF enzyme | Catalytic core for azetidine formation | Recombinantly expressed in E. coli [5] [10] |

| Fe(II) solution | Cofactor for enzyme reconstitution | Anaerobic preparation essential [5] [10] |

| Oâ‚‚-saturated buffer | Oxidant for initiating catalysis | Reaction initialization [5] [10] |

| Ascorbate/DTT | External reductant for multiple turnovers | Maintains diiron center reduction state (Supplementary Fig. 7 [5]) |

| Dansyl chloride (DnsCl) | Derivatization agent for LC-MS detection | Enables product visualization and quantification [5] [10] |

| L-Ile, L-Val analogs | Substrate specificity mapping | Comprehensive activity profiling [5] [10] |

| Polyoxin A standard | Authentic standard for PA identification | Product verification (Supplementary Fig. 5 [5]) |

| Boc-L-Pra-OH (DCHA) | N-cyclohexylcyclohexanamine;(2S)-2-[(2-methylpropan-2-yl)oxycarbonylamino]pent-4-ynoic acid | This product, N-cyclohexylcyclohexanamine;(2S)-2-[(2-methylpropan-2-yl)oxycarbonylamino]pent-4-ynoic acid (CAS 63039-49-6), is a dicyclohexylamine (DCHA) salt of a Boc-protected amino acid for research use only (RUO). It is not for personal, veterinary, or household use. |

| Methyl (tert-butoxycarbonyl)-L-leucinate | Methyl (tert-butoxycarbonyl)-L-leucinate, CAS:63096-02-6, MF:C12H23NO4, MW:245.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Mechanistic Workflow and Pathway Relationships

The experimental characterization of azetidine biosynthesis involves a logical progression from genetic validation to biochemical mechanism elucidation. The following diagram maps this workflow and the relationships between key experimental approaches:

Transition to a New Biosynthetic Paradigm

The historical limitations of SAM-dependent and α-KG-dependent pathways created a compelling need for alternative azetidine biosynthesis mechanisms. The constraints of these established pathways—particularly their metabolic costs, limited product diversity, and restricted substrate scope—hindered progress in both understanding natural product biosynthesis and developing biocatalytic applications [5] [10] [11].

The recent discovery of the non-haem iron-dependent pathway featuring PolF represents a significant paradigm shift in azetidine biosynthesis [5] [10] [11]. This new mechanism operates through a fundamentally different biochemical strategy, utilizing a μ-peroxo-Fe(III)₂ intermediate for unactivated C–H bond cleavage and proceeding through radical mechanisms for C–N bond formation [5] [10]. Unlike previous pathways, the PolF system transforms simple, readily available amino acid precursors (L-Ile, L-Val) into azetidine derivatives via 3,4-desaturated intermediates, bypassing the requirement for expensive cofactors [5] [10].

This breakthrough not only addresses the historical limitations outlined in this review but also substantially expands the toolbox available for synthetic biology and drug development. The mechanistic insights from PolF catalysis, combined with the auxiliary function of PolE in enhancing desaturation flux, provide a new foundation for engineering azetidine biosynthesis in heterologous systems and developing novel biocatalytic applications for pharmaceutical development [5] [7] [10].

The azetidine ring, a strained four-membered nitrogen-containing heterocycle, is a crucial structural feature in numerous bioactive compounds and pharmaceuticals [5] [11]. Its high ring strain (approximately 25.4 kcal molâ»Â¹) makes it both challenging to synthesize and a valuable scaffold in drug discovery [5]. For decades, the biosynthetic pathways leading to this ring in natural products remained largely enigmatic. Prior to the discovery of the Polyoxin system, only two known enzymatic mechanisms for azetidine formation were characterized: (1) S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-dependent enzymes that catalyze an intramolecular nucleophilic cyclization, and (2) α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) and Fe-dependent oxygenases that facilitate radical-mediated oxidative C–C bond formation [5] [11]. Both these routes depend on metabolically expensive precursors, limiting their utility for biocatalytic applications [11].

The antifungal nucleoside polyoxin A, produced by Streptomyces cacaoi, contains an azetidine amino acid known as polyoximic acid (PA) [5] [12]. Early isotope-labelling studies indicated that PA is derived from L-isoleucine (L-Ile), suggesting the existence of a novel biosynthetic mechanism distinct from the known pathways [5]. Within the polyoxin biosynthetic gene cluster, two genes coding for putative enzymes, PolE and PolF, were identified as likely participants in the construction of the azetidine ring, yet their precise functions were unknown [5] [11] [13]. This guide details the elucidation of this novel pathway, focusing on the groundbreaking discovery of the non-haem iron-dependent enzymes PolE and PolF.

The Polyoxin System: Gene Cluster and Essential Enzymes

The polyoxin biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC0000877) from Streptomyces cacaoi subsp. asoensis contains the genes polE and polF, which were initially annotated as a hypothetical protein and a putative molybdopterin oxidoreductase, respectively [13]. Functional analysis through gene knockout experiments established their critical roles. Disruption of the polF gene completely abolished polyoxin A production (<1% of wild-type), demonstrating that PolF is essential for PA biosynthesis. In contrast, a polE mutant produced a reduced but detectable amount of polyoxin A (~10% of wild-type), indicating that PolE plays a supporting role in enhancing the biosynthetic flux [5].

Table 1: Key Enzymes in the Polyoxin Azetidine Biosynthetic Pathway

| Enzyme | Gene Locus | Protein Family | Cofactors | Essential for Production? | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PolF | ABX24498.1 [13] | HDO (Haem-oxygenase-like dimetal oxidase/or oxygenase) superfamily [5] | Diiron (Feâ‚‚) [5] | Yes (<1% yield without polF) [5] | Catalyzes azetidine ring formation from L-Ile and L-Val [5] |

| PolE | ABX24499.1 [13] | DUF6421 family [5] | Iron (Fe) and pterin [5] | No (~10% yield without polE) [5] | Assists PolF by catalyzing desaturation of L-Ile [5] |

Functional Characterization of the Key Enzyme PolF

PolF is an HDO Superfamily Enzyme

Bioinformatic analysis revealed that PolF is a member of the haem-oxygenase-like dimetal oxidase and/or oxygenase (HDO) superfamily, an emerging group of diiron-dependent enzymes that activate Oâ‚‚ to perform diverse oxidative reactions [5]. Unlike previously characterized HDOs, PolF possesses the unique ability to construct an azetidine ring.

In Vitro Reconstitution of PolF Activity

To confirm its function, PolF was heterologously expressed in E. coli and purified. The enzyme was reconstituted with Fe(II) under anaerobic conditions for functional assays [5].

Table 2: Summary of PolF Activity Assay Conditions and Results

| Assay Component | Condition | Observation | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Active PolF | PA production detected | PolF is necessary for reaction [5] |

| Heat-inactivated PolF | No PA detected | ||

| Cofactor | With Fe(II) | PA production detected | Fe(II) is essential metal cofactor [5] |

| With other transition metals (e.g., Mn, Co, Ni) | No PA detected | ||

| Atmosphere | Aerobic (Oâ‚‚ present) | PA production detected | Oâ‚‚ is essential co-substrate [5] |

| Anaerobic | No PA detected | ||

| Reductant | With ascorbate or DTT | Multiple turnovers observed | External reductant required for catalytic cycling [5] |

| No external reductant | Limited turnover |

The assay mixture, containing L-Ile and Fe-reconstituted PolF, was initiated by introducing an Oâ‚‚-saturated buffer. Subsequent LC-MS analysis of the dansyl chloride-derivatized products revealed a compound with a mass 4 Da less than L-Ile, which was identified as polyoximic acid (PA) by comparison with an authentic standard from polyoxin A [5].

Substrate Specificity and Catalytic Versatility of PolF

Investigation into PolF's substrate scope revealed its ability to accept L-valine (L-Val) as a substrate, converting it to 3-methylene-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (MAA). Among other proteogenic amino acids, only L-leucine and L-methionine yielded minor products, primarily hydroxylated derivatives, but no azetidine rings, highlighting a specificity for medium-sized aliphatic amino acids and suggesting the β-methyl group is critical for cyclization [5].

Under single-turnover conditions, PolF was found to catalyze three distinct reactions on L-Val: desaturation (producing 3,4-dehydrovaline, 3,4-dh-Val), hydroxylation (producing 3- and 4-hydroxyvaline), and C–N bond formation (producing an azetidine-containing product and an intermediate aziridine, 3-dimethylaziridine-2-carboxylic acid). This demonstrates the remarkable catalytic versatility of a single HDO enzyme [5].

The Supporting Role of PolE

Functional characterization showed that PolE, a member of the DUF6421 family, is an Fe and pterin-dependent oxidase [5]. It catalyzes the desaturation of L-Ile to a 3,4-desaturated intermediate. This activity primes the substrate for PolF, increasing the efficiency and specificity of the pathway by providing a more direct flux toward the azetidine ring compared to the multi-functional catalysis of PolF alone [5].

Proposed Biosynthetic Pathway and Mechanism

Based on genetic, enzymological, and structural data, the biosynthetic route to the azetidine ring in polyoximic acid can be summarized as follows.

Diagram 1: Biosynthetic pathway to polyoximic acid. PolE and PolF can act sequentially or PolF can act alone on L-Ile.

The mechanism of PolF involves a μ-peroxo-Fe(III)₂ intermediate that is directly responsible for the challenging cleavage of the unactivated C–H bond [5]. Subsequent steps, including the crucial C–N bond formation, are proposed to proceed through radical mechanisms [5] [11]. The crystal structure of PolF in complex with L-Ile has provided critical insights into how the enzyme facilitates this strained ring cyclization [5].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Enzyme Purification and Reconstitution

- Heterologous Expression: Express PolF in E. coli and purify using standard chromatographic techniques (e.g., affinity and size-exclusion chromatography) [5].

- Apo-Enzyme Preparation: Isolate PolF in its apo-form, largely devoid of metal cofactors [5].

- Anaerobic Reconstitution: Incubate apo-PolF with a 3-fold molar excess of Fe(II) under strictly anaerobic conditions (e.g., in a glovebox or using Schlenk techniques) [5].

- Removal of Excess Metal: Pass the reconstituted mixture through a desalting column (e.g., PD-10) to remove unbound Fe(II). Typical reconstitution yields PolF with ~1.5 equivalents of bound Fe(II), consistent with the weak metal affinity of HDO enzymes in the absence of substrate [5].

PolF Activity Assay

- Reaction Setup: Prepare an anaerobic mixture containing the reconstituted PolF (~1.5 eq Fe) and substrate (e.g., 1 mM L-Ile or L-Val) in a suitable buffer [5].

- Initiate Reaction: Start the reaction by rapidly adding an Oâ‚‚-saturated buffer to the mixture. Include controls without enzyme, without Fe(II), without Oâ‚‚, and with heat-inactivated enzyme [5].

- Include Reductant: For multiple turnover assays, include an external reductant like ascorbate or dithiothreitol (DTT) in the reaction mixture to re-reduce the diiron centre [5].

- Product Derivatization and Analysis:

- Derivatize reaction products with dansyl chloride (DnsCl) [5].

- Analyze derivatized products using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) [5].

- Identify polyoximic acid by comparison of retention time and mass with an authentic standard. A product with a mass of -4 Da relative to the substrate indicates the formation of the azetidine ring [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying the Polyoxin Azetidine Pathway

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Key Details / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Apo-PolF Enzyme | Catalytic core for in vitro mechanistic studies. | Heterologously expressed and purified from E. coli [5]. |

| Fe(II) Salts | Essential metallo-cofactor for reconstituting active PolF and PolE. | e.g., Ammonium iron(II) sulfate or FeSOâ‚„; handling requires anaerobic conditions [5]. |

| L-Isoleucine (L-Ile) | Native biosynthetic substrate. | Used in activity assays and kinetic studies [5]. |

| L-Valine (L-Val) | Alternative substrate for probing enzyme mechanism and specificity. | Yields 3-methylene-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (MAA) [5]. |

| Oâ‚‚-saturated Buffer | Co-substrate for the oxidative reaction. | Prepared by bubbling oxygen through the buffer immediately before assay initiation [5]. |

| External Reductants | Maintains catalytic cycling during multiple turnovers. | e.g., Ascorbate or Dithiothreitol (DTT) [5]. |

| Dansyl Chloride (DnsCl) | Derivatization agent for enhancing LC-MS detection of amino acid substrates and products. | Reacts with amine groups for sensitive fluorescence and MS detection [5]. |

| Authentic PA Standard | Reference for confirming product identity in chromatographic analyses. | Can be prepared from hydrolyzed polyoxin A [5]. |

| Boc-L-Ala-OH | Boc-L-Ala-OH, CAS:15761-38-3, MF:C8H15NO4, MW:189.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dabcyl acid | Dabcyl acid, CAS:6268-49-1, MF:C15H15N3O2, MW:269.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The discovery of the Polyoxin system, centered on the enzymes PolE and PolF, represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of azetidine biosynthesis. This pathway unveils a third, distinct mechanistic strategy for forming the strained azetidine ring, fundamentally different from SAM-dependent cyclization or α-KG/Fe-dependent oxygenase mechanisms [5] [11]. The characterization of PolF as a diiron-dependent HDO enzyme capable of catalyzing desaturation, hydroxylation, and radical-mediated C–N bond formation significantly expands the known catalytic repertoire of this enzyme superfamily [5].

From a biotechnological perspective, this novel pathway is particularly promising. Unlike previous routes, it utilizes readily available proteinogenic amino acids (L-Ile, L-Val) as starting materials, bypassing the need for expensive precursors and potentially enabling more efficient biocatalytic applications for the synthesis of azetidine-containing pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals [11]. Future research will likely focus on further elucidating the detailed radical rearrangement mechanism, engineering PolF for altered substrate scope and enhanced stability, and exploring its application in synthetic biology for the production of valuable azetidine compounds.

Azetidine, a saturated four-membered nitrogen-containing heterocycle, is a crucial structural motif in numerous bioactive compounds and drugs [5] [11]. Its high ring strain (approximately 25.4 kcal molâ»Â¹) makes it both energetically challenging to form and a valuable substrate for various chemical transformations [5]. In nature, the azetidine ring is found in important molecules such as polyoximic acid (PA), the azetidine amino acid present in the antifungal nucleoside polyoxin A [5] [11]. Early isotope-labelling studies indicated that PA is derived from L-isoleucine (L-Ile), suggesting a biosynthetic pathway distinct from previously known mechanisms [5].

Until recently, the characterized enzymatic mechanisms for azetidine ring formation were limited. The best-known pathways involve S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-dependent enzymes that catalyze an intramolecular nucleophilic cyclization, or α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)- and Fe-dependent oxygenases that mediate a radical-based oxidative C–C bond formation [5] [11]. A significant limitation of these routes is their dependence on metabolically or chemically expensive precursors, which restricts their utility for biocatalytic applications [11]. The biosynthesis of the azetidine ring in polyoxin, therefore, presented an intriguing enigma. Within the polyoxin biosynthetic gene cluster, two genes encoding putative enzymes, PolE and PolF, were proposed to be involved in PA biosynthesis, but their specific functions and mechanisms remained unknown [5] [11]. This whitepaper details the elucidation of PolF as a novel non-haem iron-dependent enzyme from the haem-oxygenase-like dimetal oxidase and/or oxygenase (HDO) superfamily, responsible for the unique transformation of L-amino acids into azetidine derivatives.

PolF: Essential Role and Catalytic Function

Genetic Evidence for PolF's Essential Role

The critical role of polF in azetidine biosynthesis was unequivocally demonstrated through targeted gene knockout experiments in Streptomyces cacaoi, the native polyoxin producer [5]. Analysis of the fermentation broth using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) revealed that inactivation of polF completely abolished the production of polyoxin A, reducing titers to below 1% of wild-type levels [5]. In contrast, a polE mutant still produced detectable amounts of polyoxin A, albeit at a significantly reduced yield (~10% of wild-type) [5]. These genetic findings established that PolF is indispensable for polyoximic acid biosynthesis, while PolE appears to play a supporting, non-essential role in enhancing biosynthetic flux.

In Vitro Characterization of PolF Activity

Recombinant PolF was expressed and purified from E. coli in its apo-form [5]. Functional characterization confirmed its activity as a diiron-dependent enzyme. Table 1 summarizes the key experimental parameters and conditions for the in vitro reconstitution of PolF activity.

Table 1: Summary of PolF Activity Assay Conditions

| Parameter | Description/Value | Function/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Form | Apo-PolF | Purified from E. coli; requires Fe(II) reconstitution |

| Metal Cofactor | Fe(II) | Essential; other transition metals (e.g., Mn, Co, Ni, Cu) could not substitute [5] |

| Reconstitution | Incubation with 3 eq. Fe(II) under anaerobic conditions | Resulted in ~1.5 eq. Fe bound per PolF, consistent with weak Fe affinity in HDOs without substrate [5] |

| Reaction Initiation | Addition of Oâ‚‚-saturated buffer | Requires molecular oxygen |

| External Reductant | Ascorbate or Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Required for multiple turnovers to re-reduce the diiron center [5] |

| Product Detection | Derivatization with dansyl chloride (DnsCl) followed by LC-MS | Enabled detection and identification of reaction products |

Assays performed under these conditions, with L-Ile as the substrate, successfully produced a compound with a molecular mass 4 Da lower than L-Ile [5]. This product was confirmed to be polyoximic acid (PA) by comparison with an authentic standard derived from polyoxin A and through structural characterization by NMR [5]. Control reactions lacking Fe(II), Oâ‚‚, or using heat-inactivated PolF yielded no PA, confirming the enzyme's specific and catalytic role in this transformation [5].

Catalytic Mechanism and Substrate Specificity

Proposed Catalytic Cycle of PolF

PolF is a member of the haem-oxygenase-like dimetal oxidase and/or oxygenase (HDO) superfamily, an emerging class of diiron enzymes that activate Oâ‚‚ for diverse oxidative reactions [5]. Mechanistic studies, including spectroscopic characterization, suggest that a μ-peroxo-Fe(III)â‚‚ intermediate is directly responsible for the initial, chemically challenging cleavage of an unactivated C–H bond (bond strength up to 101 kcal molâ»Â¹) [5]. Subsequent steps, including the critical C–N bond formation that closes the azetidine ring, are proposed to proceed via radical mechanisms [5]. The following diagram illustrates the current understanding of the PolF catalytic cycle, integrating the formation of key intermediates.

Diagram 1: Proposed catalytic cycle of PolF, highlighting the key μ-peroxo-Fe(III)₂ intermediate and radical-mediated C-N bond formation.

Identification of Intermediates and Reaction Landscape

The catalytic versatility of PolF was revealed through experiments using L-valine (L-Val) as a substrate, which allowed for the detection and characterization of several intermediates [5]. Under multiple turnover conditions, the primary product from L-Val is 3-methyene-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (MAA) [5]. However, under single-turnover conditions (using 2 equivalents of Fe(II) and no external reductant), several intermediates were observed, indicating that PolF can catalyze three distinct reactions on a single substrate [5]:

- Desaturation: Formation of 3,4-dehydrovaline (3,4-dh-Val), the major initial product.

- Hydroxylation: Formation of 3-hydroxyvaline (3-OH-Val) and 4-hydroxyvaline (4-OH-Val).

- C–N Bond Formation: Formation of 3-dimethylaziridine-2-carboxylic acid (Azi), a direct precursor to the azetidine ring.

Notably, when 3,4-dh-Val was used as a substrate, it was quantitatively converted to MAA, identifying it as a key intermediate en route to the azetidine product [5]. This suggests a pathway where desaturation precedes azetidine ring closure.

Substrate Scope and Specificity

The substrate specificity of PolF was probed using the 20 proteogenic amino acids. Table 2 summarizes the reactivity of different amino acid substrates with PolF, highlighting its selectivity for medium-sized aliphatic amino acids.

Table 2: Substrate Specificity of PolF

| Substrate | Product(s) | Relative Reactivity / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| L-Isoleucine (L-Ile) | Polyoximic Acid (PA) | Native substrate; azetidine ring formed efficiently [5] |

| L-Valine (L-Val) | 3-Methylene-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (MAA) | Azetidine ring formed efficiently [5] |

| L-Leucine (L-Leu) | Mostly hydroxylation products; minor desaturation | No azetidine product detected [5] |

| L-Methionine (L-Met) | Mostly hydroxylation products; minor desaturation | No azetidine product detected [5] |

| Other Proteogenic Amino Acids | No detectable products | PolF reacts selectively with medium-size aliphatic amino acids [5] |

| L-allo-Ile, D-Ile, D-allo-Ile | Small amounts of azetidine products | Stereochemistry at C2 and C3 is important but not absolutely essential [5] |

The data indicate that PolF exhibits a strict requirement for a β-methyl group for successful azetidine formation, as neither L-Leu nor L-Met yielded azetidine products [5]. The enzyme also shows a degree of stereochemical flexibility, as all stereoisomers of isoleucine were transformed into azetidine products, albeit less efficiently [5].

The Supporting Role of PolE

While PolF alone is sufficient to convert L-Ile to PA, the biosynthetic pathway is assisted by PolE, a member of the DUF6421 family [5] [11]. Functional characterization revealed that PolE is an iron and pterin-dependent oxidase that specifically catalyzes the desaturation of L-Ile to the 3,4-dehydroisoleucine intermediate [5]. By providing this desaturated intermediate, PolE increases the flux through the PolF-catalyzed reaction, making the overall biosynthesis of PA more specific and efficient [5]. This explains the genetic evidence showing that a polE knockout strain still produces polyoxin, but at a significantly reduced titer [5].

Experimental Workflow and Methodologies

This section provides detailed protocols for key experiments used to characterize PolF, from gene to mechanism. The overall workflow is summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram 2: Integrated experimental workflow for characterizing PolF function, encompassing genetics, biochemistry, and structural biology.

Genetic Inactivation and Metabolite Analysis

- Method: In-frame deletion of polE and polF genes in Streptomyces cacaoi [5].

- Procedure: The target gene is replaced with a selectable marker via homologous recombination. Mutants are selected and verified by genomic analysis. The wild-type and mutant strains are cultured under polyoxin-producing conditions [5].

- Analysis: Fermentation broths are analyzed by Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). The presence or absence of polyoxin A is determined by comparing chromatographic retention times and mass spectra with authentic standards [5].

In Vitro Enzyme Activity Assay

- Enzyme Preparation: Apo-PolF is purified from E. coli. The enzyme is reconstituted by incubation with a 3-fold molar excess of Fe(II) under anaerobic conditions (e.g., in an anaerobic glovebox). Unbound iron is removed using a desalting column [5].

- Reaction Setup: Inside the anaerobic chamber, PolF is mixed with substrate (e.g., L-Ile, L-Val) in a suitable buffer. The reaction is initiated by transferring the mixture to an Oâ‚‚-saturated buffer outside the chamber [5].

- Detection and Quantification:

- Derivatization: Reaction products can be derivatized with dansyl chloride (DnsCl) to improve detection [5].

- LC-MS Analysis: Products are separated by reverse-phase LC and detected by MS. Identification is based on mass loss (-4 Da for azetidine products) and comparison to authentic standards. Quantification can be achieved via calibration curves [5].

- Single-Turnover Experiments: Conducted with a stoichiometric amount of Fe(II) (2 eq. per PolF) and no external reductant to trap and observe reaction intermediates [5].

Structural and Mechanistic Probes

- Crystallography: X-ray crystallography of PolF, particularly in complex with substrates like L-Ile, provides atomic-level insights into the active site architecture and substrate binding mode, informing the mechanism of C–N bond formation [5]. Advanced methods like time-resolved crystallography and automated multiconformer model building (e.g., with tools like qFit) can further reveal dynamic changes and conformational heterogeneity during catalysis [14] [15].

- Spectroscopic Characterization: Techniques such as Mössbauer and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy are used to characterize the diiron cluster and identify reactive oxygen intermediates (e.g., the μ-peroxo-Fe(III)₂ species) during the catalytic cycle [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying PolF and Related Iron-Dependent Enzymes

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Apo-PolF Enzyme | Catalytic core for in vitro functional studies | Recombinantly expressed and purified from E. coli [5] |

| Fe(II) Salts (e.g., Fe(NHâ‚„)â‚‚(SOâ‚„)â‚‚) | Reconstitution of the active diiron cofactor | Must be handled under anaerobic conditions to prevent oxidation [5] |

| External Reductants (Ascorbate, DTT) | Maintains diiron center in reduced state for multiple catalytic turnovers | Essential for sustained enzyme activity in assays [5] |

| Deuterated Solvents & NMR Standards | Structural elucidation of novel products and intermediates | Used for NMR characterization of PA, MAA, and other intermediates [5] |

| Derivatization Agents (e.g., Dansyl Chloride) | Enhances detection sensitivity for LC-MS analysis | Facilitates identification and quantification of amino acid-based products [5] |

| Synchrotron Radiation | High-intensity X-ray source for protein crystallography | Enables high-resolution structure determination of PolF and complexes [16] |

| Automated Model Building Software (e.g., qFit) | Models conformational heterogeneity from high-resolution crystallographic or cryo-EM data | Identifies alternative protein conformations relevant to catalysis [15] |

| XL413 hydrochloride | XL413 hydrochloride, CAS:1169562-71-3, MF:C14H13Cl2N3O2, MW:326.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SB-277011 dihydrochloride | SB-277011 dihydrochloride, MF:C28H32Cl2N4O, MW:511.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The identification and characterization of PolF as a non-haem iron-dependent HDO enzyme has unveiled a novel and remarkable biocatalytic strategy for the formation of the strained azetidine ring. Unlike previously known mechanisms, PolF utilizes a μ-peroxo-Fe(III)₂ intermediate to drive a radical-mediated process that directly transforms simple L-amino acids into azetidine carboxylates. Its catalytic prowess, which includes desaturation, hydroxylation, and C–N bond formation activities on a single platform, coupled with the auxiliary desaturation function of PolE, provides a more efficient and potentially generalizable route to these valuable structures. The insights gained from the genetic, enzymological, and structural studies of PolF not only solve a long-standing biosynthetic puzzle but also significantly expand the known catalytic repertoire of the HDO superfamily. For researchers in drug development and synthetic biology, PolF represents a promising biocatalytic tool for the sustainable production of azetidine-containing building blocks, opening new avenues for the creation of pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals.

Mechanistic Insights and Practical Applications of Non-Haem Iron Enzymes

This technical guide outlines integrated genetic and enzymological workflows for characterizing biosynthetic pathways, using the recent elucidation of azetidine amino acid biosynthesis by non-haem iron-dependent enzymes as a foundational case study. We provide detailed methodologies for gene knockout, enzyme production, functional characterization, and structural analysis tailored to researchers investigating specialized metabolic pathways. The protocols emphasize practical considerations for handling oxygen-sensitive metalloenzymes and detecting transient reaction intermediates, with specific application to the PolF and PolE enzymes responsible for azetidine ring formation in polyoxin antifungal compounds.

The biosynthesis of azetidine-containing amino acids represents a significant biochemical challenge due to the high ring strain (25.4 kcal molâ»Â¹) characteristic of four-membered heterocycles [5]. Recent breakthroughs in understanding polyoximic acid biosynthesis in Streptomyces cacaoi have revealed novel non-haem iron-dependent enzymes capable of catalyzing this energetically demanding transformation [5] [6] [7]. This guide frames core genetic and enzymological techniques within this research context, providing standardized workflows for pathway validation and enzyme characterization that can be applied to similar biosynthetic systems.

The azetidine ring is a crucial structural element in many bioactive compounds and drugs, yet its biosynthetic origins have remained largely enigmatic until recent studies identified PolF as a haem-oxygenase-like dimetal oxidase and/or oxygenase (HDO) superfamily member capable of transforming L-isoleucine and L-valine into their azetidine derivatives via a 3,4-desaturated intermediate [5]. The accompanying PolE enzyme, a DUF6421 family member, functions as an Fe and pterin-dependent oxidase that increases flux through the pathway by catalyzing desaturation of L-Ile [5].

Genetic Workflow: Gene Knockout and Functional Analysis

Gene Knockout Strategies

Gene knockout techniques enable researchers to determine gene function by observing phenotypic consequences of specific gene inactivation [17]. In the context of azetidine biosynthesis, knockout experiments established the essential role of polF in polyoximic acid formation [5].

2.1.1 CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Knockout CRISPR-Cas9 has revolutionized gene knockout efficiency across diverse organisms [18]. The system utilizes a guide RNA (gRNA) to direct the Cas9 nuclease to a specific genomic locus, creating a double-strand break (DSB) that is repaired predominantly through error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), resulting in frameshift mutations and gene inactivation [18] [19].

Critical Design Considerations:

- Target Selection: For complete knockout, target early exons common to all transcript variants [19]

- Off-target Assessment: Use tools like CRISPOR or CRISPRdirect to minimize off-target effects [19]

- Critical Exon Strategy: Delete exons meeting these criteria: present in all splicing variants, total nucleotide count not a multiple of 3, >50 bp from termination codon, and disruption destroys ≥50% of coding sequence [19]

2.1.2 Homologous Recombination Traditional homologous recombination-based methods remain valuable for specific applications, particularly when large deletions or precise modifications are required [17]. This approach involves creating a DNA construct with long homology arms flanking a drug selection marker, which replaces the target gene via the cell's native repair mechanisms [17].

Experimental Protocol: Microbial Gene Knockout

The following protocol was applied successfully in Streptomyces cacaoi to elucidate azetidine biosynthesis genes [5]:

Step 1: Target Identification and gRNA Design

- Identify target gene sequence within biosynthetic gene cluster

- Design gRNAs targeting critical exons or functional domains

- For polF and polE, target sequences within DUF6202 and DUF6421 domains respectively

Step 2: Vector Construction

- Clone selected gRNAs into appropriate Cas9-expression vector

- Include selection markers (antibiotic resistance) for stable transformants

- Incorporate inducible systems for essential gene analysis

Step 3: Transformation and Selection

- Introduce construct into host via electroporation or conjugation

- Plate on selective media and incubate until colonies form

- Screen colonies by PCR for desired genomic modifications

Step 4: Phenotypic Analysis

- Culture knockout mutants under polyoxin-producing conditions [5]

- Analyze metabolites via LC-MS comparing knockout to wild-type

- For polF knockout: complete loss of polyoxin A production (<1% of wild-type) [5]

- For polE knockout: significantly reduced but detectable polyoxin A (~10% of wild-type) [5]

Step 5: Genotype Validation

- Sequence target locus to confirm intended mutation

- Verify absence of off-target modifications through whole-genome sequencing

- Assess expression levels of flanking genes to rule out polar effects

Data Interpretation and Validation

Knockout results must be interpreted cautiously, as compensatory mechanisms may mask phenotypic effects [17]. For essential genes, conditional knockouts using Cre-loxP or similar systems enable temporal control of gene expression [17]. In the azetidine pathway, the differential phenotypes of polE versus polF knockouts revealed their distinct functional contributions, with PolF being essential while PolE serves an auxiliary role [5].

Enzymological Workflow: Recombinant Enzyme Production and Characterization

Enzyme Production and Purification

Functional characterization begins with recombinant production of catalytically active enzyme [5]:

Expression in E. coli:

- Clone gene into appropriate expression vector (e.g., pET series)

- Transform into expression strain (e.g., BL21(DE3))

- Induce expression with IPTG at optimal temperature (often 16-18°C for metalloenzymes)

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and lyse via sonication or French press

Purification of Metalloenzymes:

- Purify via affinity chromatography (His-tag, GST-tag, etc.)

- For iron-dependent enzymes like PolF: perform under anaerobic conditions when necessary

- Remove unbound metal via desalting chromatography

- Reconstitute apo-enzyme with excess Fe(II) (3 eq.) under anaerobic conditions

- Remove excess metal and verify incorporation (PolF contained 1.5 eq. Fe(II) after reconstitution) [5]

Enzyme Activity Assays

Standard Activity Assay for PolF-like Enzymes [5]:

- Prepare assay mixture anaerobically in glove box

- Include: enzyme (PolF), substrate (L-Ile or L-Val), excess Fe(II), buffer

- Initiate reaction by adding Oâ‚‚-saturated buffer

- Terminate reaction at appropriate timepoints

- Derivatize products with dansyl chloride (DnsCl) for detection

- Analyze via LC-MS

Key Controls:

- No enzyme (background reaction)

- No Fe(II) (metal dependence)

- No Oâ‚‚ (oxygen dependence)

- Heat-inactivated enzyme (enzyme dependence)

- Alternative metals (specificity)

Table 1: Substrate Specificity of PolF

| Substrate | Major Product | Relative Activity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-isoleucine | Polyoximic acid (PA) | 100% | Natural substrate |

| L-valine | 3-methylene-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (MAA) | ~80% | Forms azetidine ring |

| L-leucine | Hydroxylation products | <5% | Minor desaturation |

| L-methionine | Hydroxylation products | <5% | Minor desaturation |

| L-allo-Ile | Azetidine products | <10% | Stereochemistry important |

| Other proteogenic amino acids | No detectable products | - | High specificity |

Kinetic Characterization

Establish kinetic parameters using optimized assay conditions [20]:

Initial Velocity Measurements:

- Vary substrate concentration while maintaining saturating other components

- Determine initial rates at each substrate concentration

- Plot data and fit to appropriate model (Michaelis-Menten, etc.)

Advanced Kinetic Analysis:

- Pre-steady-state kinetics for mechanistic studies

- Single-turnover experiments to isolate specific steps

- For PolF: single-turnover revealed 3,4-dh-Val as major intermediate (0.23 minâ»Â¹) followed by Azi, 4-OH-Val and 3-OH-Val (0.15 minâ»Â¹, 0.14 minâ»Â¹ and 0.036 minâ»Â¹) [5]

Reductant Dependence: Assess requirement for external reductants (ascorbate, DTT) which are often necessary for multiple turnovers in HDO enzymes [5].

Structural and Mechanistic Characterization

Spectroscopic Methods

Multiple spectroscopic techniques provide insight into metalloenzyme active sites:

UV-Visible Spectroscopy [20]:

- Monitor reaction progress and intermediate formation

- Identify charge-transfer bands characteristic of metal centers

Advanced Spectroscopic Techniques:

- Mössbauer spectroscopy for iron oxidation and coordination states

- EPR for paramagnetic intermediates

- For PolF: identification of μ-peroxo-Fe(III)₂ intermediate responsible for C–H cleavage [5]

Structural Biology Approaches

X-ray Crystallography [20]:

- Grow high-quality crystals of native and substrate-bound forms

- Collect diffraction data at synchrotron sources

- Solve structure by molecular replacement or experimental phasing

- For PolF: structures revealed active site architecture and substrate positioning [5]

Alternative Structural Methods:

- Cryo-EM for large complexes or difficult-to-crystallize proteins

- NMR for solution dynamics and conformational changes [20]

Reaction Intermediate Analysis

Trapping and Identification:

- Use single-turnover conditions with limited Oâ‚‚

- Quench reactions at various timepoints

- Analyze intermediates via LC-MS and NMR

- For PolF: identified 3,4-dehydrovaline (3,4-dh-Val) as key intermediate quantitatively converted to MAA [5]

Mechanistic Probes:

- Isotope labeling (²H, ¹â¸O) to track atom fate

- Substrate analogs to test specificity

- Radical traps to identify radical intermediates

Biosynthesis of Azetidine Amino Acids: A Case Study

The biosynthesis of polyoximic acid in Streptomyces cacaoi provides a comprehensive example integrating these genetic and enzymological approaches [5].

Early isotope-labelling experiments indicated L-isoleucine as the polyoximic acid precursor, suggesting a novel biosynthetic mechanism distinct from SAM-dependent or α-ketoglutarate-dependent routes [5]. Gene cluster analysis identified polE and polF as candidate biosynthetic genes, though their specific functions were unknown.

Functional Characterization of PolF

Genetic knockout established PolF as essential for polyoximic acid biosynthesis [5]. In vitro reconstitution demonstrated that PolF alone could convert L-Ile to polyoximic acid, with absolute requirement for Fe(II) and Oâ‚‚ [5]. Substrate specificity studies revealed that PolF accepts L-Ile and L-Val as primary substrates, generating azetidine products, while other amino acids yield only minor hydroxylation products [5].

Mechanistic studies identified PolF as an HDO superfamily member that utilizes a μ-peroxo-Fe(III)₂ intermediate for unactivated C–H bond cleavage [5]. The subsequent C–N bond formation proceeds through a radical mechanism, with 3,4-desaturated intermediates serving as precursors to azetidine ring formation.

Role of PolE

While PolF alone can catalyze the complete transformation, PolE enhances pathway efficiency by catalyzing Fe and pterin-dependent desaturation of L-Ile, increasing flux through the pathway [5]. This auxiliary function explains the reduced but detectable polyoxin production in polE knockout strains.

Integrated Reaction Mechanism

The current mechanistic model for azetidine formation includes:

- Initial C–H activation by μ-peroxo-Fe(III)₂ species

- Formation of 3,4-desaturated intermediate

- Radical-mediated C–N bond formation

- Azetidine ring closure with concomitant reduction

Diagram 1: Azetidine Biosynthesis Pathway

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Azetidine Biosynthesis Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Specific Examples | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Engineering | |||

| CRISPR-Cas9 system | Targeted gene knockout | Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 | Most widely used system [19] |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Targets Cas9 to specific locus | CRISPOR-designed sequences | Minimize off-target effects [19] |

| Homologous recombination vectors | Traditional gene replacement | pKO vectors with selection markers | Lower efficiency than CRISPR [17] |

| Enzyme Characterization | |||

| Affinity chromatography resins | Protein purification | Ni-NTA (His-tag), Glutathione (GST-tag) | Maintain anaerobic conditions for metalloenzymes |

| Iron supplements | Metalloenzyme reconstitution | Fe(II) salts (e.g., FeSOâ‚„) | Add anaerobically to prevent oxidation [5] |

| Anaerobic chamber | Oxygen-sensitive procedures | PolF assay setup | Essential for Fe(II)-dependent enzymes [5] |

| Analytical Tools | |||

| LC-MS systems | Metabolic and enzyme analysis | Q-TOF, Orbitrap instruments | Detect -4 Da mass change in azetidine formation [5] |

| NMR spectroscopy | Structural characterization of products | ¹H, ¹³C NMR | Confirm azetidine ring structure [5] |

| X-ray crystallography | Enzyme structure determination | Synchrotron sources | Reveal active site architecture [5] [20] |

| Specialized Reagents | |||

| Dansyl chloride (DnsCl) | Product derivatization for detection | PolF assay derivatization | Enhances LC-MS sensitivity [5] |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate | PEP-dependent reactions | Pyruvyltransferase assays | Substrate for pyruvylation [21] |

| UDP-sugar donors | Glycosyltransferase assays | SCWP biosynthesis studies | Lipid-linked repeat formation [21] |

The integration of genetic knockout strategies with detailed enzymological characterization provides a powerful framework for elucidating biosynthetic pathways, as demonstrated by the recent breakthroughs in understanding azetidine amino acid biosynthesis. The case study of PolF and PolE highlights how coordinated application of these techniques can unravel novel enzymatic mechanisms, even for chemically challenging transformations like four-membered ring formation.

These workflows establish a standardized approach applicable to diverse biosynthetic systems, particularly those involving metalloenzymes and specialized metabolism. The continued refinement of gene editing technologies coupled with advanced structural and mechanistic enzymology promises to accelerate the discovery and characterization of novel enzymatic functions with potential applications in drug development and biocatalysis.