The Biosynthetic Logic of Polyketide Synthases: From Assembly Line Mechanisms to Drug Discovery and Engineering

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the biosynthetic logic underpinning polyketide synthases (PKSs), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Biosynthetic Logic of Polyketide Synthases: From Assembly Line Mechanisms to Drug Discovery and Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the biosynthetic logic underpinning polyketide synthases (PKSs), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of PKS classification, architecture, and the assembly-line mechanism of polyketide chain elongation and modification. The scope extends to advanced methodological approaches, including chemoenzymatic synthesis and combinatorial biosynthesis for generating novel compounds. The content addresses key challenges in PKS engineering, such as optimizing protein-protein interactions and overcoming substrate specificity constraints, and presents validation strategies through case studies of clinically relevant polyketides. By synthesizing insights across these four core intents, this review serves as a strategic resource for leveraging PKS logic in natural product discovery and bioengineering.

Deconstructing the PKS Assembly Line: Core Principles and Architectural Diversity

Polyketides represent one of the largest families of natural products with profound impacts on human health, including many clinically essential drugs such as the antibiotic tetracycline, the immunosuppressant rapamycin, and the cholesterol-lowering agent lovastatin [1]. These structurally diverse compounds are biosynthesized by polyketide synthases (PKSs), enzymatic systems that share a core biosynthetic logic with fatty acid synthases (FASs) through the iterative decarboxylative condensation of acyl-CoA precursors [2] [3]. However, PKSs have evolved extraordinary mechanisms to generate vastly greater structural diversity than FASs through controlled variations at each step of the assembly process [3]. The current scientific understanding classifies PKSs into three major paradigms—type I, II, and III—based on their distinctive protein architectures, catalytic mechanisms, and evolutionary relationships [1]. This review provides a comprehensive technical overview of these three PKS paradigms, framed within the context of their biosynthetic logic and their expanding applications in drug discovery and development.

Comparative Analysis of PKS Architectures and Mechanisms

The three PKS paradigms represent nature's solution to producing chemical diversity through variations on a conserved catalytic theme. Table 1 summarizes the fundamental characteristics of each system, highlighting their distinct approaches to polyketide biosynthesis.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Type I, II, and III Polyketide Synthases

| Feature | Type I PKS | Type II PKS | Type III PKS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Architecture | Large, multimodular multidomain proteins | Discrete, dissociated monofunctional enzymes | Homodimeric enzymes |

| Carrier Protein | Integrated ACP domains | Discrete ACP protein | ACP-independent |

| Catalytic Process | Assembly-line, non-iterative | Iterative multicomponent | Iterative condensing enzyme |

| Chain Length Control | Defined by module number | Primarily by KS/CLF complex | By active site pocket |

| Representative Products | Erythromycin, rapamycin [1] | Tetracycline, daunorubicin [1] [3] | Flavolin, alkyl-resorcinols [1] [4] |

| Substrate Selection | AT domains in cis or trans | MAT (malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase) | Direct acyl-CoA utilization |

| Reductive Processing | Variable reductive domains per module | Variable reductive enzymes | Limited to condensation |

Type I PKS: The Assembly Line Paradigm

Type I PKSs are multifunctional enzymes organized into modular assembly lines, where each module houses a set of distinct, non-iteratively acting catalytic domains responsible for one cycle of polyketide chain elongation [1]. The prototypical example is the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase (DEBS), which synthesizes the macrocyclic core of erythromycin A through a highly coordinated, vectorial biosynthetic process [1] [2]. Each canonical module minimally contains three core domains: a ketosynthase (KS) that catalyzes chain elongation, an acyltransferase (AT) that selects and loads extender units, and an acyl carrier protein (ACP) that shuttles the growing polyketide chain between domains [2]. Additionally, modules may contain variable combinations of reductive domains - ketoreductase (KR), dehydratase (DH), and enoylreductase (ER) - that modify the β-keto group after each condensation cycle [2].

The catalytic cycle of a Type I PKS module involves three fundamental reactions: transacylation (transfer of an extender unit onto the ACP), elongation (decarboxylative Claisen condensation catalyzed by the KS), and translocation (movement of the growing chain to the next module) [2]. This process is distinguished from iterative PKSs and FASs by its requirement for two distinct translocation steps - entry from the previous module and exit to the next module - necessitating precise extraction and reinsertion of the polyketide intermediate at each stage [2]. Notably, while DEBS represents the canonical cis-AT Type I PKS, evolution has produced trans-AT PKSs where multiple AT-less modules share a stand-alone AT protein that acts iteratively in trans [1] [2].

Type II PKS: The Iterative Aromatic Specialist

Type II PKSs are multienzyme complexes that carry a single set of iteratively acting catalytic activities, typically producing aromatic polyketides through the controlled generation of reactive poly-β-ketone intermediates [1] [3]. The core "minimal PKS" consists of three essential components: a ketosynthase (KS), a chain length factor (CLF) that controls the number of elongation cycles, and an acyl carrier protein (ACP) [3] [5]. This system generates polyketide intermediates of specific chain lengths, with decaketides (C20) being most common, though nonaketides (C18) and other lengths also occur [5]. The poly-β-ketone backbone then undergoes specific cyclization and aromatization patterns mediated by cyclases/aromatases, followed by various tailoring modifications to produce the final bioactive compound [3].

Recent research has revealed unexpected flexibility in some Type II PKS systems. For instance, the var and oxt clusters in Streptomyces varsoviensis demonstrate dual chain-length programming, producing both decaketide-derived tetracyclines and nonaketide-derived tricyclic aromatic polyketides from the same minimal PKS [5]. This challenges the traditional view that individual Type II PKSs produce polyketide intermediates with a fixed, invariant chain length [5].

Type III PKS: The Minimalist Condensing Enzyme

Type III PKSs, also known as chalcone synthase-like PKSs, are homodimeric enzymes that function as iteratively acting condensing enzymes without requirement for an ACP cofactor [1] [4]. These systems directly utilize acyl-CoA substrates rather than ACP-tethered intermediates, representing a more simplified architectural approach to polyketide biosynthesis [1]. Despite their structural simplicity, Type III PKSs exhibit remarkable functional flexibility, as demonstrated by MMAR_2190 from Mycobacterium marinum, which can concurrently biosynthesize alkyl-resorcinols, acyl-phloroglucinols, and alkyl-α-pyrones from a single catalytic core [4]. This product diversity stems from alternative cyclization modes of the same polyketide intermediate, highlighting the mechanistic versatility of these systems [4].

Experimental Methodologies for PKS Research

Gene Cluster Identification and Manipulation

The study of PKS systems begins with the identification and analysis of their biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). For Type II PKSs, a common approach involves targeted strategies for identifying specific classes of BGCs, such as those for tetracycline biosynthesis [5]. Once identified, BGCs can be activated through various methods, including overexpression of pathway-specific regulatory genes, as demonstrated with the var cluster where SARP family regulator overexpression led to production of new metabolites [5]. For heterologous expression, the ExoCET technology can be employed to construct E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle plasmids containing complete BGCs, enabling expression in various streptomycete hosts [6].

Chassis Development for Heterologous Expression

Selecting an optimal host is critical for efficient PKS expression and natural product discovery. Streptomyces species serve as ideal chassis for heterologous expression of Type II PKSs due to their native compatibility with polyketide biosynthesis [6]. Development of high-performance chassis involves in-frame deletion of endogenous PKS gene clusters to mitigate precursor competition, as demonstrated with the creation of Chassis2.0 from Streptomyces aureofaciens J1-022 [6]. This chassis shows enhanced production efficiency for diverse Type II polyketides, including a 370% increase in oxytetracycline production compared to conventional strains [6].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for PKS Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ExoCET Technology | Construction of E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle plasmids | Enables cloning of large PKS gene clusters [6] |

| Chassis2.0 | Heterologous expression host for Type II PKS | High-yield Streptomyces aureofaciens with endogenous clusters deleted [6] |

| BioPKS Pipeline | Automated retrobiosynthesis tool combining PKS and monofunctional enzymes | Integrates RetroTide (PKS design) and DORAnet (monofunctional enzymes) [7] |

| ClusterCAD 2.0 Database | Platform for PKS engineering and design | Provides curated PKS domains and modules for combinatorial biosynthesis [7] |

Computational Design and Engineering

Advanced computational tools are revolutionizing PKS research and engineering. The BioPKS pipeline represents an automated retrobiosynthesis tool that combines the design of chimeric Type I PKSs with monofunctional enzymatic pathways [7]. This system includes two complementary components: RetroTide for designing PKS carbon scaffolds and DORAnet for planning post-PKS tailoring steps [7]. These tools enable the in silico design of pathways for complex natural products, expanding the accessible chemical space for biomanufacturing.

Gene Conversion-Associated Engineering

Evolutionary-inspired approaches provide powerful strategies for PKS engineering. Gene conversion-associated engineering mimics natural evolutionary processes where genetic material is exchanged between adjacent homologous modules [8]. This approach involves identifying highly homologous DNA fragments between modules, then using these regions as boundaries for domain swapping [8]. Key guidelines include: (i) designing DNA fragments spanning from "GTNAH" to "HHYWL" signature motifs, (ii) prioritizing catalytic elements from the same BGC, and (iii) when using foreign elements, selecting those with high sequence homology to the host BGC [8].

Visualization of PKS Research Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationships and experimental workflows in contemporary PKS research, highlighting the interconnected approaches to understanding and engineering these complex biosynthetic systems.

The three PKS paradigms represent nature's elegant solutions to generating chemical diversity through variations on a conserved biosynthetic theme. While the type I, II, and III classifications have served the scientific community well, emerging research continues to reveal systems that challenge these categorical boundaries, highlighting the remarkable evolutionary plasticity of these enzymatic systems [1]. Current research is increasingly focused on leveraging this understanding for targeted engineering approaches, including the development of optimized chassis strains [6], computational design tools [7], and evolutionary-inspired engineering strategies [8]. As these approaches mature, they promise to unlock the full potential of PKS systems for drug discovery and development, enabling the efficient production of both natural and "unnatural" natural products with optimized pharmaceutical properties. The continued integration of structural biology, bioinformatics, and synthetic biology will undoubtedly yield new insights into the molecular mechanisms governing these fascinating enzymatic assembly lines and expand our ability to harness their biosynthetic potential.

Polyketide synthases (PKSs) represent a family of multifunctional enzymes that catalyze the biosynthesis of an extraordinarily diverse array of complex natural products with clinically valuable properties, including antibiotic, antifungal, anticancer, and immunosuppressant activities [2] [9]. These enzymatic systems operate on a biosynthetic logic closely related to that of fatty acid synthases (FAS), building complex molecules through the iterative decarboxylative Claisen condensation of acyl-CoA building blocks [10] [11]. However, PKSs generate far greater structural diversity than FASs through controlled variations in building block selection, chain length, and the programmed reduction of β-carbonyl groups at each elongation cycle [10]. The modular architecture of type I PKSs, in particular, embodies a remarkable molecular assembly line where discrete catalytic units operate in sequence to channel growing polyketide chains along uniquely defined pathways in a process termed vectorial biosynthesis [2]. This in-depth technical guide examines the fundamental organization of the core ketosynthase-acyltransferase-acyl carrier protein (KS-AT-ACP) domains and their auxiliary partners, framing this architectural logic within the broader context of programmable biosynthetic engineering.

Architectural Organization of PKS Modules

The Core KS-AT-ACP Domains

The minimal catalytic unit of a type I modular PKS consists of three essential domains that form the foundation of polyketide chain assembly: the ketosynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), and acyl carrier protein (ACP). These domains operate in concert to execute two universal reactions shared by all PKSs and FASs: transacylation and elongation [2].

Ketosynthase (KS): The KS domain serves as the gatekeeper of chain elongation, catalyzing the decarboxylative Claisen condensation between the growing polyketide chain and the extender unit [11]. This carbon-carbon bond-forming reaction represents the principal exergonic step within the catalytic cycle and is typically rate-limiting [2] [11]. Biochemical and evolutionary analyses indicate that KS domains strongly co-evolve with upstream domains, suggesting they function as part of the preceding catalytic unit—a concept formalized in the "PKS exchange unit" model where a module begins with the AT and ends after the KS [11].

Acyltransferase (AT): The AT domain is responsible for selecting and loading the appropriate extender unit (e.g., malonyl-CoA, methylmalonyl-CoA) onto the PKS assembly line [10]. It catalyzes a thiol-to-thioester exchange that transfers the α-carboxyacyl building block from acyl-CoA onto the phosphopantetheinyl arm of the ACP domain [2]. AT domains typically exhibit strict substrate specificity, with some exclusively accepting malonyl-CoA while others preferentially load methylmalonyl-CoA or other substituted malonyl extender units [12] [10].

Acyl Carrier Protein (ACP): The ACP serves as the central hub of the biosynthetic process, shuttling the growing polyketide chain between catalytic domains [13]. ACP function requires post-translational modification by a phosphopantetheinyl transferase that installs a 4'-phosphopantetheine (Ppant) arm, which serves as a flexible tether for covalent attachment of polyketide intermediates [13]. The inherent flexibility of the ACP, coupled with the 18-Å reach of its Ppant arm, enables it to interact with multiple catalytic partners throughout the elongation cycle [13].

Table 1: Core Catalytic Domains in Type I Modular PKSs

| Domain | Catalytic Function | Key Features | Essential for Elongation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ketosynthase (KS) | Decarboxylative Claisen condensation | Active site cysteine for covalent substrate attachment; gatekeeper function | Yes |

| Acyltransferase (AT) | Selection and loading of extender unit | Specificity for malonyl-/methylmalonyl-CoA; can function in cis or trans | Yes |

| Acyl Carrier Protein (ACP) | Shuttling of intermediates | Phosphopantetheine arm for thioester linkage; highly flexible structure | Yes |

Structural Organization and Interdomain Linkers

High-resolution structural studies of intact PKS modules have revealed an asymmetric organization with two reaction chambers that operate asynchronously [14]. The core KS-AT didomain forms a stable structural unit, with the AT domain further divided into subdomains that undergo conformational changes during catalysis [12]. Critical to the structural integrity and function of these domains are the interdomain linker regions, particularly the KS-AT linker and the post-AT linker [12].

The post-AT linker, a approximately 30-residue segment that wraps around both the AT domain and the KS-AT linker, has been shown to be essential for chain elongation but not for the transacylation activity of the AT domain [12]. Experimental dissection of DEBS module 3 demonstrated that while AT domains lacking the post-AT linker could still be methylmalonylated and transfer the methylmalonyl unit to ACP, they failed to support KS-catalyzed condensation [12]. This highlights the critical role of linker regions in facilitating proper domain-domain interactions necessary for the coordination of catalysis.

Auxiliary Domains for β-Keto Processing

Following each chain elongation event, the β-keto group of the nascent polyketide intermediate can be processed by a variable set of reductive domains that determine the final oxidation state at each carbon center. The reductive loop of a PKS module can include up to three auxiliary domains that act sequentially on the β-carbonyl [2] [10].

Ketoreductase (KR): The KR domain catalyzes the NADPH-dependent reduction of the β-keto group to a β-hydroxyl group, introducing the first level of reductive processing [10]. KRs exhibit stereospecificity, generating hydroxyl groups with specific chiral configurations that significantly influence the three-dimensional structure of the final polyketide product [12].

Dehydratase (DH): Following ketoreduction, the DH domain catalyzes the dehydration of the β-hydroxy group to form an α,β-unsaturated enoyl intermediate [2]. This elimination reaction introduces a double bond at the β-position, further reducing the oxidation state of the carbon chain.

Enoylreductase (ER): The final reductive step is catalyzed by the ER domain, which reduces the enoyl double bond to a fully saturated methylene group using NADPH as a cofactor [2]. The presence of all three reductive domains results in complete reduction of the β-carbon to the most reduced state possible.

Table 2: Auxiliary Reductive Domains in Type I Modular PKSs

| Domain | Catalytic Function | Cofactor Requirement | Resulting Functional Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ketoreductase (KR) | Reduces β-keto to β-hydroxy | NADPH | Secondary alcohol |

| Dehydratase (DH) | Eliminates water to form enoyl | None | α,β-unsaturated thioester |

| Enoylreductase (ER) | Reduces enoyl to acyl | NADPH | Fully saturated carbon chain |

The combinatorial presence or absence of these reductive domains, along with variations in their stereochemical preferences, generates remarkable diversity in the final polyketide structures. For example, in DEBS, Module 2 contains only a KR domain, resulting in a hydroxyl group at the corresponding position, while Module 4 contains KR, DH, and ER domains, leading to a fully reduced carbon center [2].

Catalytic Cycle and Vectorial Biosynthesis

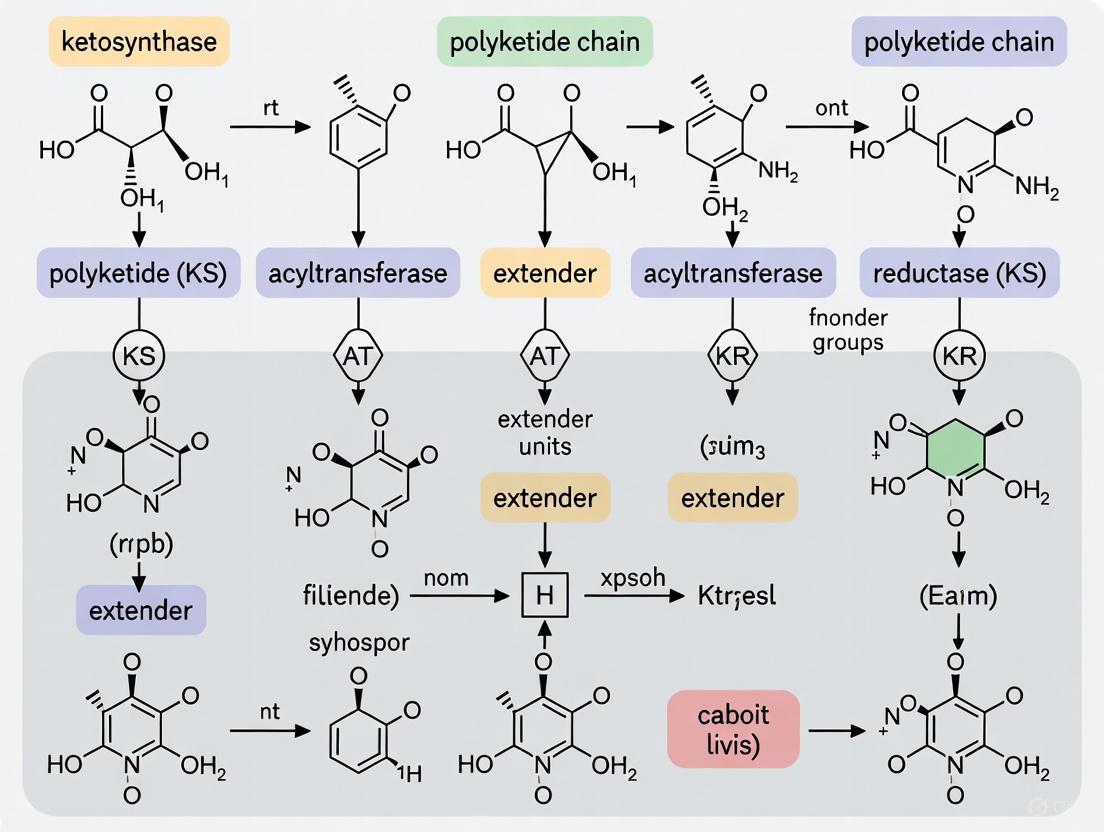

The coordinated activity of core and auxiliary domains enables the sequential elongation and processing of the polyketide chain through a carefully orchestrated catalytic cycle. As illustrated in Figure 1, the cycle begins with the AT domain selecting and loading an extender unit onto the ACP domain (transacylation). Concurrently, the KS domain receives the growing polyketide chain from the upstream module (entry translocation). The KS then catalyzes decarboxylative condensation between the extender unit and the polyketide chain (elongation), followed by β-keto processing by the reductive domains. Finally, the elongated chain is transferred to the KS domain of the next module (exit translocation), completing the cycle [2].

Figure 1: Catalytic Cycle of a PKS Module

A defining feature of assembly-line PKSs is the vectorial biosynthesis of polyketide chains, where intermediates are channeled along a uniquely defined sequence of modules, each used only once in the overall catalytic cycle [2]. This process involves two distinct translocation events: entry translocation (transfer from the upstream ACP to the current KS) and exit translocation (transfer from the current ACP to the downstream KS) [2]. This stands in contrast to iterative systems where the growing chain toggles back and forth between the same KS-ACP pair throughout biosynthesis [2].

The translocation mechanism remains incompletely understood but represents an evolutionary innovation that enables assembly-line PKSs to function as programmed biosynthetic factories. Recent structural studies have captured PKS modules in different catalytic states, showing the ACP domain docked alternately with the AT domain (during transacylation) and with the KS domain (during condensation), demonstrating the dynamic nature of these interactions [14].

Experimental Dissection and Reconstitution of PKS Modules

Domain Dissection Methodologies

Understanding PKS structure-function relationships has been advanced significantly through domain dissection approaches, wherein individual domains are expressed as standalone proteins and their activities characterized biochemically. The following protocol outlines the key steps for dissecting and reconstituting PKS modules based on successful experiments with DEBS module 3 [12]:

Identification of Domain Boundaries: Define authentic domain boundaries based on limited proteolysis and high-resolution structural data. Critical junction sites, such as the EEAPERE sequence following the KS3 domain in DEBS, serve as natural separation points [12].

Construct Design for Soluble Expression: Design expression constructs that include essential linker regions. For AT domains, inclusion of the complete KS-to-AT linker at the N-terminus and the post-AT linker at the C-terminus is crucial for solubility and activity [12].

Heterologous Expression and Purification: Express recombinant domains in suitable host systems (e.g., E. coli). Purify proteins using affinity chromatography followed by size exclusion chromatography to obtain monodisperse preparations [12].

Functional Assays: Develop specific assays to monitor individual domain activities:

- AT Acylation: Incubate AT with [¹⁴C]methylmalonyl-CoA and analyze covalent intermediate formation by radio-SDS-PAGE [12].

- KS Acylation: Monitor KS loading using N-acetyl cysteamine thioester analogs of polyketide intermediates [12].

- Condensation Activity: Reconstitute the complete elongation cycle by combining KS, AT, and ACP with appropriate substrates and detect products by radio-TLC [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for PKS Domain Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| N-Acetyl Cysteamine (NAC) Thioesters | Surrogate substrates for KS acylation | Mimic native ACP-tethered intermediates [12] |

| [¹⁴C]-Labeled Methylmalonyl-CoA | Radiolabeled extender unit | Tracing AT-mediated loading and transacylation [12] |

| Discrete ACP Domains | Standalone carrier proteins | Studying protein-protein interactions and substrate channeling [12] [13] |

| Post-AT Linker Peptides | Critical structural elements | Reconstitution of condensation activity in dissected systems [12] |

| Phosphopantetheinyl Transferase | ACP activation enzyme | Conversion of apo-ACP to holo-ACP [13] |

Engineering Perspectives and Future Directions

The modular architecture of PKSs presents extraordinary opportunities for biosynthetic engineering through the rational design and recombination of catalytic domains. Two primary strategies have emerged for engineering novel polyketide pathways: module swapping and combinatorial domain assembly [15] [11]. However, these approaches face significant challenges related to domain-domain compatibility and the gatekeeping activity of KS domains, which often reject non-natural substrates from upstream modules [11].

Evolutionary analyses suggest that alternative module boundaries may enhance the success of engineering efforts. The PKS exchange unit (XU) model, which defines a module as beginning at the AT and ending after the KS (in contrast to the genetic organization), aligns better with functional constraints and co-evolution patterns [11]. Engineering studies utilizing XU boundaries have demonstrated improved activity in chimeric PKSs, particularly in trans-AT systems [11].

Recent advances in structural biology, including the first high-resolution structures of intact PKS modules, have revealed unprecedented details of interdomain interactions and asynchronous catalytic chambers [14]. These structural insights, combined with powerful computational tools like AlphaFold2 for protein structure prediction, are paving the way for more rational design principles in PKS engineering [11]. The integration of synthetic biology approaches—including standardized synthetic interfaces such as docking domains, coiled-coils, and SpyTag/SpyCatcher systems—further enables the programmable assembly of functional PKS chimeras [15].

As our understanding of the fundamental architectural principles governing PKS module organization continues to deepen, so too does our capacity to harness these remarkable molecular machines for the programmed biosynthesis of structurally complex and pharmacologically active polyketides.

Polyketides represent one of the largest classes of bioactive natural products, with profound importance in modern medicine due to their diverse pharmacological activities, including antibiotic, antifungal, anticancer, antiviral, antihypercholesterolemic, and immunosuppressant properties [3] [9]. These compounds are assembled by polyketide synthases (PKSs), enzymatic systems that share a core biosynthetic logic with fatty acid synthases, iteratively building complex molecules from simple precursors through decarboxylative Claisen condensation reactions [3] [16]. However, PKSs generate incredible structural diversity through strategic variations at each stage of synthesis, incorporating different building blocks and processing intermediates through tailored biochemical modifications [17]. Understanding the precise mechanisms of the biosynthetic stages—from starter unit loading to chain termination and release—provides the foundation for engineering novel polyketides with enhanced medicinal properties, representing a central focus in contemporary natural product research [3] [8].

This technical guide examines the core biosynthetic stages of polyketide assembly, framing these processes within the broader context of biosynthetic logic that governs PKS function. We present detailed experimental methodologies, quantitative data summaries, and visualization tools to equip researchers with practical resources for advancing polyketide engineering and drug development.

PKS Architecture and Classification

Polyketide synthases are classified into three primary types based on their architectural organization and catalytic mechanism [18]. Type I PKSs are large, multimodular proteins with catalytic domains covalently linked in a specific sequence, functioning like an assembly line where each module is responsible for one round of chain extension [19] [16]. These are further subdivided into modular systems (non-iterative) and iterative systems where the same module is reused multiple times [16]. Type II PKSs consist of discrete, monofunctional enzymes that form dissociable complexes and typically work iteratively to produce aromatic polyketides [3] [18]. The minimal components include a ketosynthase chain-length factor heterodimer (KSα-KSβ) and an acyl carrier protein (ACP) [18]. Type III PKSs (chalcone synthase-like) are homodimeric enzymes that utilize free acyl-CoA substrates directly without requirement for an ACP partner [18].

Despite their architectural differences, all PKS types share a common biosynthetic logic centered on the iterative assembly of simple carboxylic acid precursors. The structural diversity of final polyketide products stems from variations in: (1) starter and extender unit selection, (2) number of elongation cycles, (3) degree of β-keto group processing after each condensation, and (4) the mechanism of chain termination and release [17] [16]. This systematic variability provides nature with a powerful toolkit for chemical diversification, which researchers are now learning to harness through PKS engineering.

The Initiation Stage: Starter Unit Loading

The biosynthesis of polyketides initiates with the selection and loading of a starter unit onto the catalytic machinery of the PKS. The starter unit provides the foundation upon which the polyketide chain is assembled and significantly influences the structural properties of the final natural product [17].

Diversity of Starter Units

PKSs incorporate a remarkable variety of starter units, efficiently introducing unusual moieties such as p-nitrobenzenes, alkynes, branched-alkyl chains, and halogenated pyrroles into polyketide scaffolds [17]. The following table summarizes key starter units and their origins in representative polyketides:

Table 1: Diversity of Polyketide Starter Units and Their Incorporation

| Starter Unit | Biosynthetic Origin | Representative Polyketide | Structural Feature Introduced |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propionyl-ACP [17] | Methylmalonyl-ACP decarboxylation by AT/DC | Lomaiviticins (2) [17] | Ethyl side chain |

| p-Nitrobenzoic acid [17] | Sequential oxidation of p-aminobenzoic acid by AurF [17] | Aureothin (3) [17] | Nitroaryl moiety |

| Pyrrolyl-Carrier Protein [17] | Dehydrogenation of L-prolyl-S-CP by RedW [17] | Undecylprodiginine (4) [17] | Pyrrole ring |

| 4,5-Dichloropyrrolyl-CP [17] | Dichlorination of Pyrrolyl-CP by PltA [17] | Pyoluteorin (7) [17] | Halogenated pyrrole |

| 4-Guanidinobutyryl-CoA [17] | Oxidative decarboxylation of L-arginine [17] | Azalomycin F3a (13) [17] | Guanidinium group |

Experimental Analysis of Starter Unit Incorporation

The investigation of starter unit biosynthesis employs targeted genetic and biochemical approaches to elucidate novel priming mechanisms.

Protocol 3.2.1: In vitro Reconstitution of Starter Unit Biosynthesis

- Objective: To characterize the enzymatic activity of a putative bifunctional acyltransferase/decarboxylase (AT/DC) in generating a propionyl-ACP starter unit.

- Reagents:

- Recombinant AT/DC enzyme (e.g., Lom62)

- Standalone ACP (e.g., Lom63) in apo-form

- Methylmalonyl-CoA

- ATP, Mg²⁺

- Analytical buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, pH 7.5-8.0)

- Methodology:

- Enzyme Purification: Clone, express, and purify the recombinant AT/DC and ACP proteins using affinity chromatography.

- Reaction Setup: Incubate the AT/DC enzyme with ACP, methylmalonyl-CoA, and necessary cofactors in analytical buffer.

- Product Analysis:

- Key Application: This approach confirmed that Lom62 selectively loads methylmalonyl-CoA onto Lom63 and subsequently decarboxylates it to yield propionyl-ACP, a novel priming mechanism for type II PKSs [17].

The Elongation Stage: Chain Extension and Processing

Following initiation, the polyketide chain undergoes iterative cycles of extension and processing, ultimately determining the carbon skeleton length and oxidation state.

Extender Unit Diversity and Incorporation

The elongation of the polyketide chain is facilitated by extender units, which contribute significantly to its structural diversity. The acyltransferase (AT) domain acts as the "gatekeeper," selecting the specific extender unit and transferring it to the ACP domain [16].

Table 2: Major Polyketide Synthase Extender Units

| Extender Unit | PKS Type(s) | Enzymatic Origin | Resulting Polyketide Structural Motif |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malonyl-CoA [16] | I, II, III [16] | Acetyl-CoA carboxylation [16] | Unsubstituted carbon backbone (β-keto) |

| (2S)-Methylmalonyl-CoA [16] | I, II [16] | Propionyl-CoA carboxylation or succinyl-CoA mutase/epimerase pathway [16] | α-Methyl branch |

| (2S)-Ethylmalonyl-CoA [16] | I, II [16] | Ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway from acetyl-CoA and crotonyl-CoA [16] | α-Ethyl branch |

| (2R)-Methoxymalonyl-ACP [16] | I (Modular) [16] | Glycolytic intermediates (1,3-bisphosphoglycerate) [16] | α-Methoxy branch |

| (2R)-Hydroxymalonyl-ACP [16] | I (Modular) [16] | Glycolytic intermediates [16] | α-Hydroxy branch |

| (2S)-Aminomalonyl-ACP [16] | I (Modular) [16] | Serine oxidation and activation [16] | α-Amino branch |

The core elongation cycle within a typical type I PKS module involves several coordinated steps [18]:

- The AT domain selects an extender unit (e.g., malonyl-CoA) and transfers it to the phosphopantetheine arm of the ACP domain.

- The KS domain catalyzes a decarboxylative Claisen condensation between the ACP-bound extender unit and the growing polyketide chain from the previous module, resulting in a two-carbon extension and a β-keto thioester.

- Optional processing of the β-keto group by a variable set of reductive domains (KR, DH, ER) follows.

Figure 1: Polyketide Chain Elongation Cycle. The diagram illustrates the coordinated action of KS, AT, and ACP domains within a PKS module to extend the polyketide chain by two carbons.

Experimental Analysis of Extender Unit Fidelity

Engineering PKSs to incorporate non-native extender units is a key strategy for drug discovery but is often hampered by the intrinsic specificity of AT domains and proofreading mechanisms.

Protocol 4.2.1: Gene Conversion-Associated AT Domain Swapping

- Objective: To successively engineer a modular PKS to alter extender unit incorporation specificity for the de novo production of analog structures.

- Reagents:

- Parent bacterial strain with target PKS gene cluster (e.g., cmm BGC for cinnamomycin).

- Donor DNA fragments from homologous BGC (e.g., mgm BGC).

- PCR reagents for amplification and assembly.

- Vectors and reagents for genetic manipulation in the host (e.g., Streptomyces).

- Methodology:

- Identify Gene Conversion Regions: Analyze homologous BGCs to locate regions of high nucleotide sequence identity, typically spanning from the C-terminus of the KS domain through the AT domain to the post-AT linker [8].

- Design Replacement Fragments: Design chimeric genes where the identified "ATc region" (e.g., from "GTNAH" to "HHYWL" motifs) from the donor BGC replaces the corresponding region in the parent PKS [8].

- Genetic Engineering: Introduce the designed constructs into the parent strain using appropriate genetic techniques (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9, REDIRECT) [8].

- Metabolite Analysis: Ferment the mutant strains and analyze extracts using HPLC and LC-MS to detect and characterize new polyketide analogs [8].

- Key Application: This strategy was successfully applied to the cinnamomycin BGC, enabling the production of mangromycin-like compounds with predicted alterations in their side chains [8].

The Termination Stage: Chain Release and Functionalization

The final stage of polyketide biosynthesis involves the release of the full-length chain from the PKS assembly line, often coupled with cyclization or other functionalization to yield the mature natural product.

Diverse Chain Termination Mechanisms

The thioesterase (TE) domain, typically found at the C-terminus of the final module in type I PKSs, is most commonly responsible for chain release [18]. The classic termination mechanism involves hydrolysis to release a linear acid or intramolecular cyclization to form a macrolactone [20] [18]. However, recent research has uncovered unprecedented and complex termination mechanisms that install unique functional groups.

A notable example is the termination process in the biosynthesis of curacin A, an anticancer agent from Lyngbya majuscula [20]. The terminal module contains adjacent sulfotransferase (ST) and thioesterase (TE) domains. Biochemical characterization revealed a novel decarboxylative chain termination mechanism:

- The ST domain selectively sulfonates the (R)-β-hydroxyl group of the full-length intermediate attached to the ACP.

- The TE domain then catalyzes hydrolysis of the thioester linkage.

- The sulfonate group acts as a leaving group, triggering successive decarboxylative elimination to form a terminal olefin, a rare moiety in the final metabolite [20].

Table 3: Polyketide Chain Termination Mechanisms and Outcomes

| Termination Mechanism | Catalytic Domain/Enzyme | Resulting Chemical Structure | Example Polyketide |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis [18] | Thioesterase (TE) [18] | Free carboxylic acid | Various fatty acids |

| Macrolactonization [18] | Thioesterase (TE) [18] | Macrolactone | 6-Deoxyerythronolide B [19] |

| Decarboxylative Elimination [20] | Sulfotransferase + Thioesterase (ST-TE) [20] | Terminal olefin | Curacin A [20] |

| Claisen Cyclization | Ketosynthase (KS) | Aromatic ring | Aromatic polyketides (e.g., Actinorhodin) |

Experimental Characterization of Chain Termination

Elucidating novel termination mechanisms requires a combination of bioinformatics, molecular biology, and rigorous in vitro biochemistry.

Protocol 5.2.1: Biochemical Characterization of a Novel Termination Module

- Objective: To reconstitute and analyze the activity of an unusual ACP-ST-TE termination module in vitro.

- Reagents:

- Cloned genes for ACP, ST, and TE domains.

- Expression vectors for protein overproduction in E. coli.

- Apo-ACP protein.

- Svp phosphopantetheinyltransferase.

- Acyl-CoA substrates for generating model ACP-linked intermediates.

- PAPS (sulfonate donor for ST).

- HPLC, FTICR-MS, GC-MS systems.

- Methodology:

- Protein Production: Express and purify individual ACP, ST, and TE domains as soluble proteins. Confirm oligomeric state via size-exclusion chromatography [20].

- Substrate Synthesis: Generate model ACP-linked substrates (e.g., 3-hydroxy-5-methoxytetradecanoyl-ACP) by loading the corresponding acyl-CoA onto apo-ACP using Svp phosphopantetheinyltransferase [20].

- Individual Enzyme Assays:

- Incubate TE with ACP-substrate to test for canonical hydrolytic release.

- Incubate ST with ACP-substrate and PAPS to test for sulfonation.

- Analyze reactions by HPLC and FTICR-MS to detect conversion and mass changes of the ACP-bound species [20].

- Coupled Reaction Assay: Incubate ACP-substrate with both ST and TE in the presence of PAPS. Analyze the reaction mixture by LC-MS for sulfonated acid product and by GC-MS for the volatile terminal olefin product [20].

- Key Application: This protocol confirmed the sequence of ST sulfonation preceding TE hydrolysis and the subsequent decarboxylative elimination, establishing a novel chain termination pathway [20].

Figure 2: Curacin A Decarboxylative Termination. The ST-TE di-domain catalyzes a two-step termination process involving sulfonation and hydrolysis, leading to decarboxylative elimination and formation of a terminal olefin [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies

Advancing research in PKS biochemistry and engineering requires a standardized set of reagents and analytical tools. The following table catalogues essential components for experimental investigations into PKS biosynthetic stages.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for PKS Studies

| Reagent / Methodology | Core Function | Key Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Apo-ACP Proteins [20] [19] | Scaffold for covalent attachment of polyketide intermediates via phosphopantetheinyl arm. | In vitro reconstitution assays; substrate loading studies. |

| Phosphopantetheinyl Transferases (e.g., Svp) [20] | Activates apo-ACP by installing the 4'-phosphopantetheine moiety from CoA. | Generation of holo-ACP and loading of acyl-CoA substrates to create ACP-linked intermediates [20]. |

| Acyl-CoA Substrates [20] [16] | Provide activated building blocks (starter and extender units) for polyketide assembly. | Feeding studies; generation of ACP-linked substrates for enzymatic assays. |

| PAPS (3'-Phosphoadenosine-5'-phosphosulfate) [20] | Universal sulfonate group donor for sulfotransferase enzymes. | Assaying novel termination steps involving sulfonation [20]. |

| HPLC & LC-MS [20] | Separation and identification of organic compounds and their modifications. | Monitoring enzyme reactions, detecting intermediate and product formation [20] [8]. |

| FTICR-MS (Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry) [20] | Ultra-high mass accuracy analysis of biomolecules and their modifications. | Precisely determining mass changes of ACP-bound intermediates during catalysis [20]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy [19] | Determination of 3D protein structure and dynamics in solution. | Solving structures of PKS domains (e.g., ACP) to understand protein-protein interactions [19]. |

The biosynthetic logic of polyketide synthases—from starter unit loading through chain elongation to termination—represents a sophisticated paradigm for the combinatorial assembly of chemical complexity in nature. A detailed understanding of each stage, supported by the experimental protocols and analytical tools summarized in this guide, is critical for the rational engineering of these systems [3]. While significant progress has been made in understanding domain function and engineering PKSs to produce novel compounds, challenges remain, particularly regarding the fidelity and yield of engineered chimeric PKSs [3] [8]. Future research will increasingly focus on the structural basis of specific protein-protein interactions between ACPs and catalytic domains [3] [19], the application of evolutionary guidance for engineering [8], and the elucidation of yet-uncharacterized termination and tailoring steps. As these efforts mature, the systematic reprogramming of PKS assembly lines will unlock a new generation of therapeutic polyketides, firmly grounded in the fundamental biosynthetic logic dissected here.

The evolution of polyketide synthases (PKSs) from iterative fatty acid synthases (FASs) to vectorial modular assembly lines represents a fundamental adaptive innovation in natural product biosynthesis. This transition enabled microorganisms to generate unprecedented chemical diversity, yielding many pharmacologically essential compounds. By examining phylogenetic relationships, structural architectures, and catalytic mechanisms, this review delineates the molecular trajectory through which iterative, generalist FAS-like precursors evolved into specialized, assembly-line PKSs capable of programmed biosynthesis. Understanding these evolutionary principles provides a framework for engineering next-generation synthases to produce novel therapeutic agents.

Polyketides constitute one of the largest families of bioactive natural products, encompassing antibiotics, antifungals, anticancer agents, and immunosuppressants [3]. Their biosynthetic machinery, represented by PKSs, shares a core catalytic logic with FASs, iteratively constructing complex carbon skeletons from simple acyl-CoA precursors through decarboxylative Claisen condensation [3] [21]. However, while FASs generate chemically monotonic fatty acid chains through repetitive use of a single set of catalytic domains, PKSs have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to introduce remarkable structural diversity by varying substrate selection, chain length, and β-carbon processing at each elongation cycle [3] [22].

The evolutionary progression from iterative FAS-like systems to vectorial modular PKS assembly lines represents a key innovation in secondary metabolism. This transition enabled organisms to produce chemically complex metabolites with specialized biological activities, many of which have been harnessed for human medicine. This review examines the fundamental evolutionary insights underlying this biosynthetic sophistication, focusing on structural, phylogenetic, and mechanistic evidence that illuminates how iterative systems gave rise to modular assembly lines.

Structural and Mechanistic Foundations

The Catalytic Core: Shared Mechanisms and Divergent Outcomes

FASs and PKSs share fundamental catalytic domains and reaction mechanisms. Both systems utilize a ketosynthase (KS) for carbon-carbon bond formation, an acyl carrier protein (ACP) for substrate shuttling, and various modifying domains for β-keto processing [3] [23]. The critical distinction lies in how these components are organized and utilized.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of FAS and PKS Architectures

| Feature | Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS) | Iterative PKS | Modular PKS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Organization | Multifunctional polypeptide with single set of domains | Single module with full catalytic complement | Multiple modules, each with specific domains |

| Catalytic Logic | Repetitive use of all domains for each elongation | Repetitive use with variable reduction levels | Vectorial; each domain used once per chain |

| Processivity | High processivity with synchronized reactions | Moderate processivity with cryptic programming | Programmed processivity with defined intermediates |

| Product Diversity | Limited to saturated hydrocarbons | Moderate diversity through substrate variation | High diversity through module combination |

| Evolutionary Relationship | Ancestral state | Intermediate evolutionary form | Derived, specialized state |

In mammalian FAS, the homodimeric enzyme contains all catalytic domains within a single polypeptide, functioning as an iterative system that performs synchronized reactions to produce saturated fatty acids [23]. Recent cryo-EM studies of human FAS reveal an open architecture where the ACP domain shuttles between catalytic sites without requiring large-scale rotational motions between condensing and modifying wings [23]. This efficient iterative mechanism stands in contrast to the programmed biosynthesis of modular PKSs.

Structural Transitions: From Reaction Chambers to Assembly Lines

Cryo-electron microscopy studies of modular PKSs have revealed architectural principles distinct from FAS. The pikromycin PKS module (PikAIII) exhibits an arch-shaped symmetric dimer with a single ACP reaction chamber in the center, allowing the ACP to access all catalytic sites within a module while excluding foreign ACPs to maintain fidelity [24]. This organization differs fundamentally from the mammalian FAS structure, where catalytic sites are more accessible [24].

The structural transition from iterative to modular systems involved the creation of discrete reaction chambers that enforce biospecificity and prevent crosstalk. In modular PKSs, the ACP from the preceding module utilizes a separate entrance outside the reaction chamber to deliver the upstream polyketide intermediate, ensuring strict linear progression through the assembly line [24].

Evolutionary Trajectory and Phylogenetic Evidence

From Iterative Precursors to Modular Descendants

The evolutionary relationship between FASs and PKSs is well-established, with PKSs thought to share a common ancestor with mammalian FAS [24]. However, the specific mechanisms through which iterative systems evolved into modular assembly lines have remained elusive until recently.

Emerging evidence suggests that iterative PKSs served as evolutionary intermediates in this transition. Genome mining approaches have revealed that iterative PKSs are more broadly distributed in bacteria than previously recognized [21]. Phylogenetic analysis of ketosynthase domains indicates tight evolutionary relationships between bacterial iterative PKSs, bacterial modular PKSs, and fungal iterative PKSs, suggesting a complex evolutionary history with multiple horizontal gene transfer events [21] [25].

A pivotal insight comes from the observation that monomodular iterative PKSs could have served as direct ancestors for multimodular PKSs through gene duplication events [21]. The high substrate specificity and chain length tolerance of iterative PKSs would make them particularly competent precursors for generating functional multimodular systems. Supporting this hypothesis, the mycolactone-producing PKS assembly line contains KS domains with >97% sequence identity yet accepts substrates of remarkably different chemistry and chain length, reminiscent of their putative iterative precursors [21].

Figure 1: Evolutionary Trajectory from FAS to Vectorial Modular PKSs. The diagram illustrates key transitional events, including gene duplication, domain specialization, and horizontal gene transfer, that facilitated the emergence of programmed assembly-line biosynthesis.

The Role of Horizontal Gene Transfer in PKS Diversification

Phylogenetic comparisons of PKS genes and 16S ribosomal DNA sequences reveal disparate evolutionary patterns, indicating that bacterial evolution and polyketide evolution proceed independently through horizontal gene transfer [25]. Studies of actinomycetes have demonstrated that strains with identical 16S rDNA sequences can harbor diverse aromatic PKS genes, while strains with divergent 16S rDNA sequences can possess highly similar KS sequences [25]. This horizontal transfer of biosynthetic gene clusters has served as a powerful driver of chemical diversity in natural products, allowing organisms to rapidly acquire new metabolic capabilities.

Experimental Approaches for Elucidating PKS Evolution

Phylogenetic Analysis and Genome Mining

Protocol 1: KS Domain Phylogenetics

- Sequence Acquisition: Retrieve ketosynthase domain sequences from characterized PKS clusters using databases such as ClusterCAD [7]

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Perform alignment using specialized algorithms (e.g., MAFFT, MUSCLE) with emphasis on conserved active site motifs

- Tree Construction: Generate phylogenetic trees using Bayesian inference and maximum likelihood methods

- Topology Comparison: Compare KS phylogenies with organismal phylogenies based on 16S rDNA to detect horizontal gene transfer events [25]

Protocol 2: Bacterial Iterative PKS Identification

- Genome Mining: Scan bacterial genomes for standalone PKS modules using strict selection criteria [21]

- KS-based Classification: Perform phylogenetic analysis of identified KS domains to classify iterative candidates

- Heterologous Expression: Express candidate PKS genes in suitable hosts (e.g., Streptomyces lividans) under strong promoters

- Product Characterization: Identify metabolic products using LC-MS/NMR to confirm iterative function [21]

Structural Biology Techniques

Protocol 3: Cryo-EM Analysis of PKS Architecture

- Sample Preparation: Tag and purify endogenous PKS complexes from native producers or heterologous systems [24] [23]

- Grid Preparation: Apply purified protein to cryo-EM grids, vitrify using liquid ethane

- Data Collection: Acquire cryo-EM images using modern detectors with dose fractionation

- Image Processing: Employ single-particle analysis with 3D classification to separate conformational states [24]

- Model Building: Rigidly fit homologous domain structures into EM densities to generate pseudo-atomic models [24]

Recent cryo-EM studies of human FAS have revealed unexpected dynamics, showing that the condensing and modifying wings exhibit unsynchronized catalytic reactions between monomers, challenging previous models of synchronized iterations [23]. Similar approaches applied to PKS systems have illuminated the structural basis for both intra-module and inter-module substrate transfer [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for PKS Evolutionary Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Expression Systems (Streptomyces lividans, E. coli) | Host organisms for pathway refactoring and characterization | Expression of bacterial iterative PKS genes for product identification [21] |

| ClusterCAD Database | Computational platform for PKS engineering and design | Retrobiosynthetic design of chimeric PKS systems [7] |

| BioPKS Pipeline | Automated retrobiosynthesis tool combining PKS and monofunctional enzymes | Designing pathways for complex natural products like cryptofolione [7] |

| 1,3-Dibromopropane (DBP) | Crosslinking reagent for ACP-KS interactions | Trapping ACP-engaged conformations in FAS and PKS structural studies [23] |

| Orlistat | Thioesterase inhibitor for human FAS | Stabilizing FAS complexes for structural analysis [23] |

| Nile Red Assay | Fluorescent dye for lipid detection | High-throughput screening of fatty acid production in engineered strains [26] |

Implications for Biosynthetic Engineering

Understanding the evolutionary principles governing PKS diversification provides powerful insights for engineering novel biosynthetic pathways. The natural evolutionary mechanisms of gene duplication, domain recombination, and horizontal gene transfer can be mimicked in laboratory settings to create chimeric PKS systems with altered product specificity [7] [25].

Emerging computational tools like BioPKS pipeline combine the deterministic logic of PKSs with the precision of monofunctional enzymes, enabling retrobiosynthetic design of complex molecules [7]. This approach mirrors nature's strategy of combining multifunctional enzymes for scaffold construction with monofunctional enzymes for structural fine-tuning.

Engineering strategies informed by evolutionary principles have already demonstrated success. For instance, modular optimization of multi-gene pathways for fatty acid production in E. coli has achieved titers of 8.6 g/L through balanced partitioning of acetyl-CoA formation, acetyl-CoA activation, and fatty acid synthase modules [26]. Similarly, domain-swapping experiments in DEBS (deoxyerythronolide B synthase) have enabled incorporation of non-natural extender units, including fluorinated precursors, expanding the chemical space accessible through engineered biosynthesis [7].

The evolutionary trajectory from iterative fatty acid synthases to vectorial modular PKS assembly lines represents a remarkable natural experiment in metabolic innovation. Through gene duplication, domain specialization, and horizontal transfer, biological systems have evolved sophisticated molecular assembly lines capable of programmed biosynthesis of complex natural products.

Future research directions include elucidating the structural determinants of intermodular communication, developing more accurate predictive models for chimeric PKS behavior, and harnessing evolutionary principles to design next-generation synthases for sustainable chemical production. By learning from nature's evolutionary playbook, we can accelerate the engineering of biosynthetic systems for drug discovery and green manufacturing.

The integration of phylogenetic, structural, and biochemical insights continues to illuminate the fundamental biosynthetic logic of polyketide synthases, providing both intellectual fascination and practical solutions to pressing challenges in medicine and sustainability.

Harnessing PKS Logic: Engineering Strategies for Novel Polyketide Production

Polyketide natural products, including clinical staples like erythromycin A (antibiotic), rapamycin (immunosuppressant), and lovastatin (anti-cholesterol), represent a cornerstone of modern therapeutics, with blockbuster drugs boasting sales exceeding $15 billion [27]. These complex molecules are biosynthesized by polyketide synthases (PKSs), enzymatic assembly lines that follow a deterministic logic to build carbon skeletons from simple acyl-CoA precursors [27] [2]. Type I PKSs, the focus of this review, are megadalton complexes organized into sequential modules. Each module minimally contains a ketosynthase (KS), an acyltransferase (AT), and an acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain, and is responsible for one round of chain elongation and potential modification of the growing polyketide [27] [2].

The biosynthetic logic is a recursive, vectorial process: the AT domain selects and loads an extender unit (e.g., malonyl-CoA or methylmalonyl-CoA) onto the ACP. The KS domain then catalyzes a decarboxylative Claisen condensation, extending the polyketide chain from the upstream module by two carbon atoms. Subsequently, optional reductive domains—ketoreductase (KR), dehydratase (DH), and enoylreductase (ER)—adjust the β-keto group's oxidation state. This process repeats, with the fully extended chain finally released from the assembly line, often by a thioesterase (TE) domain [27] [2]. Understanding and harnessing this logic is paramount for drug discovery, as it enables the rational redesign of PKSs to produce novel analogs with enhanced bioactivity or to combat antibiotic resistance [27] [28]. Chemoenzymatic synthesis, which merges the precision of enzymatic transformations with the flexibility of synthetic chemistry, has emerged as a powerful strategy to achieve this goal, with synthetic thioesters serving as indispensable probes [27] [29].

Synthetic Thioesters: Indispensable Tools for PKS Manipulation

Synthetic thioesters are biomimetic analogs of native acyl-CoA or acyl-ACP intermediates. Their primary role is to bypass specific steps of the native PKS pathway, allowing researchers to probe enzyme function, interrogate biosynthetic pathways, and incorporate unnatural chemical moieties into polyketide structures [27] [30].

N-Acetylcysteamine (SNAC) Thioesters

The N-acetylcysteamine (SNAC) thioester is the most widely used and versatile proxy for native phosphopantetheine-linked intermediates [27] [30]. Its popularity stems from its structural similarity to the native coenzyme A (CoA) thioester handle, commercial availability, ease of synthesis, and lack of pungent odor compared to alternatives like thiophenol [27].

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Chemoenzymatic PKS Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Chemical Structure/Type | Primary Function in PKS Research |

|---|---|---|

| SNAC Thioester | N-Acetylcysteamine thioester | Biomimetic probe for acyl-CoA and acyl-ACP intermediates; used for in vitro reconstitution, substrate specificity assays, and precursor-directed biosynthesis [27] [30]. |

| Diimide Couplers (e.g., EDC, DCC) | Carbodiimide-based reagents | Activate carboxylic acids for direct coupling with SNAC to form thioesters [27]. |

| Meldrum's Acid Adducts | 2,2-Dimethyl-1,3-dioxane-4,6-dione | Pyrolysis yields β-keto thioesters cleanly, releasing CO₂ and acetone [27]. |

| Discrete Thioesterases (e.g., NanE) | Type II thioesterase enzyme | Hydrolyzes ACP-bound or SNAC-linked full-length polyketide to release the final product; demonstrates substrate specificity for glycosylated vs. aglycone products [31]. |

Synthetic Methodologies for Thioester Construction

Several robust chemical methods have been developed to synthesize these often-reactive and unstable thioester probes [27] [30].

- Direct Coupling with SNAC: The most common method involves coupling the carboxylic acid of the desired substrate with the free thiol of SNAC using diimide coupling reagents such as ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), or diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) [27].

- Trans-thioesterification: This two-step strategy first involves forming a thiophenyl thioester, which then undergoes a mild trans-thioesterification reaction with SNAC or CoA. This is particularly useful for fragile substrates resistant to direct coupling conditions [27].

- Pyrolysis of Meldrum's Acid Adducts: This method is highly efficient for constructing sensitive β-keto thioesters. Pyrolysis of the Meldrum's acid adduct cleanly releases carbon dioxide and acetone, yielding the desired β-keto thioester [27].

- Enzymatic Ligation: Complementary to chemical synthesis, enzymes like MatB (a malonyl-CoA ligase) can ligate malonate derivatives to CoA, providing a bio-based route to building blocks usable in both in vitro and in vivo settings [27].

Experimental Workflows and Core Applications

The application of synthetic thioesters enables several key experimental paradigms for studying and engineering PKSs. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow integrating these approaches.

Precursor-Directed Biosynthesis and Mutasynthesis

This approach feeds synthetic SNAC-thioesters mimicking native PKS intermediates to either wild-type or genetically engineered PKS systems. If the PKS enzymes exhibit sufficient substrate promiscuity, they will process the unnatural precursor, leading to a "non-natural" natural product [27] [28]. A classic example is feeding fluorinated or allylated extender unit analogs to the DEBS system, resulting in polyketides with fluorine atoms or terminal alkene handles regioselectively incorporated into their scaffolds [7].

Detailed Protocol: In Vitro Precursor-Directed Biosynthesis

- Synthesis: Prepare the unnatural SNAC-thioester (e.g., allylmalonyl-SNAC) using one of the synthetic methods described in Section 2.2. Purify and characterize the compound (NMR, MS).

- Enzyme Preparation: Isolate and purify individual PKS modules, multidomain complexes, or full PKS proteins from a heterologous host like E. coli or Streptomyces.

- Reaction Setup: In a suitable reaction buffer (e.g., pH 7.0-7.5 Tris-HCl), combine the following:

- Purified PKS enzyme(s).

- Unnatural SNAC-thioester (typical final concentration 0.1 - 1.0 mM).

- Cofactors as required (e.g., NADPH for reductive domains, Mg²⁺).

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at a permissive temperature (e.g., 25-30°C) for several hours.

- Product Extraction: Terminate the reaction by acidification or heat. Extract the products with an organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate).

- Analysis and Purification: Analyze the crude extract by LC-MS to detect new product formation. Purify the target analog using preparative HPLC or chromatography for full structural elucidation (NMR) and biological testing.

Probing Enzyme Mechanism and Specificity

Synthetic thioesters are vital tools for mechanistic enzymology. For instance, studies on the discrete thioesterase NanE in nanchangmycin biosynthesis used SNAC-thioesters of the full-length polyketide and its aglycone to quantitatively characterize the enzyme's function. The assay revealed NanE had a nearly 17-fold preference for hydrolyzing the glycosylated nanchangmycin-SNAC over its aglycone counterpart, providing crucial evidence that thioesterase-catalyzed hydrolysis is the final step in the pathway [31]. Furthermore, site-directed mutagenesis of NanE's catalytic triad (Ser96, His261, Asp120) confirmed their essential role, solidifying our understanding of thioesterase chemistry [31].

Computational Guide for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

Transitioning between chemical and enzymatic steps can be inefficient. New computational tools like minChemBio and the BioPKS pipeline are being developed to plan hybrid synthesis routes that minimize these costly transitions [32] [7].

minChemBio uses a curated database of over 1.8 million chemical and 57,000 biological reactions. Its algorithm plans synthetic routes that minimize switches between chemical and biological reaction vessels, streamlining the overall process as demonstrated for bioplastic precursors [32].

The BioPKS pipeline integrates two tools: RetroTide for designing chimeric type I PKSs to build carbon scaffolds, and DORAnet for planning post-PKS tailoring using monofunctional enzymes. This in silico tool successfully proposed pathways for complex therapeutics like cryptofolione and basidalin, showcasing the power of combining multifunctional PKSs with precise tailoring enzymes [7].

Another tool, ACERetro, employs a Synthetic Potential Score (SPScore) to unify synthesis planning. The SPScore, derived from machine learning models trained on massive reaction databases (USPTO for chemistry, ECREACT for biology), heuristically guides whether a given intermediate is more promisingly synthesized by a chemical or enzymatic reaction, leading to routes for 46% more test molecules than previous state-of-the-art tools [33].

Synthetic thioesters, particularly SNAC derivatives, have cemented their role as indispensable tools for dissecting and reprogramming the biosynthetic logic of PKSs. They provide a direct conduit between synthetic organic chemistry and enzymatic biosynthesis, enabling researchers to probe complex protein-protein interactions, study domain specificity with quantitative precision, and generate diverse polyketide analogs. The future of this field lies in the deeper integration of these experimental strategies with powerful and emerging computational tools like BioPKS and SPScore-guided planning. This synergy between chemical synthesis, mechanistic enzymology, and computational design will undoubtedly accelerate the discovery and development of novel polyketide-based therapeutics to address pressing human health challenges.

Modular polyketide synthases (PKSs) function as enzymatic assembly lines, orchestrating the stepwise biosynthesis of structurally complex natural products with significant pharmaceutical value, including antibiotics, anticancer agents, and immunosuppressants [34] [2]. The biosynthetic logic of these systems is governed by a collinear architecture where each catalytic module is responsible for one round of polyketide chain elongation and modification [2]. A typical elongation module contains core domains—ketosynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), and acyl carrier protein (ACP)—and optional processing domains—ketoreductase (KR), dehydratase (DH), and enoylreductase (ER) [34]. The AT domain plays a critical role in this process by selecting a specific extender unit, typically malonyl-CoA or methylmalonyl-CoA, and loading it onto the ACP [34] [35].

Building block engineering focuses on reprogramming the biosynthetic machinery to incorporate non-native starter and extender units, thereby expanding the chemical diversity of polyketide scaffolds. This strategy leverages the inherent or engineered promiscuity of key catalytic domains, particularly the AT domain, to activate and incorporate structurally diverse building blocks [34] [35]. The fundamental logic of PKSs posits that controlled alterations to the building block repertoire can predictably alter the final polyketide structure, enabling the rational design of novel analogs. This review details the experimental strategies and mechanistic insights underlying the expansion of starter and extender unit diversity within the framework of PKS biosynthetic logic.

Engineering Strategies for Starter and Extender Unit Diversity

Acyltransferase (AT) Domain Engineering

The AT domain is the primary determinant of extender unit specificity and thus represents a major target for engineering efforts. Rational engineering strategies have included domain swaps, motif exchanges, and site-directed mutagenesis to alter substrate selectivity [34] [35].

- Domain Swapping: Replacing native AT domains with heterologous ATs possessing different inherent specificities can redirect the incorporation of extender units. This approach has been successfully implemented in both cis-AT and trans-AT PKSs [34] [36]. For example, an AT swap in the first module of the lipomycin PKS, combined with a reductive loop exchange, enabled the production of the fragrance compound 3-isopropyl-6-methyltetrahydropyranone [36].

- Active-Site Engineering: Targeted mutagenesis of AT active site residues can fine-tune or completely switch specificity without perturbing the overall protein architecture. A seminal study demonstrated that mutation of a conserved tryptophan residue could switch an AT's specificity from ACP-linked to coenzyme A (CoA)-linked extender units, opening a new route to diversification [35]. In the pikromycin PKS, mutagenesis of the final two modules enabled the unprecedented incorporation of consecutive non-natural extender units into the macrolactone core [35].

Precursor-Directed Biosynthesis and Pathway Engineering

Precursor-directed biosynthesis supplements the native cellular metabolism with synthetic, non-natural precursor analogs, leveraging the inherent promiscuity of PKS enzymes [35].

- Extender Unit Synthesis and Activation: The limited diversity of natural extender units has been expanded by employing malonyl-CoA synthetases to activate diverse C2-substituted malonates into their corresponding CoA-thioesters in vivo. A native malonyl-CoA synthetase from Streptomyces cinnamonensis was used to generate allyl-, propargyl-, and propyl-CoAs, leading to the production of monensin analogues [35].

- Halogenated Analogues: Halogenases such as SalL can be utilized to generate chlorinated and fluorinated malonyl-CoA analogs. Once incorporated into the polyketide chain, these halogens serve as chemical handles for further diversification via downstream cross-coupling reactions [35].

- In vitro Enzymatic Synthesis: The native promiscuity of enoyl-thioester carboxylase/reductases (ECRs) has been leveraged to produce non-natural extender units in vitro, providing a purified and controlled source of building blocks for PKS reactions [35].

The table below summarizes key engineered building blocks and their biosynthetic origins.

Table 1: Engineered Starter and Extender Units for Polyketide Diversification

| Building Block Type | Specific Example | Biosynthetic Origin/Engineering Strategy | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Halogenated Extender | Chlorinated/fluorinated mCoA | Halogenase (SalL) catalysis [35] | Introduces bioorthogonal handles for downstream chemistry |

| Alkyl Extender | Allyl-, Propargyl-, Propyl-CoA | Malonyl-CoA synthetase from S. cinnamonensis [35] | Production of monensin analogs with modified side chains |

| Non-natural Consecutive Extenders | Consecutive non-native units | AT domain mutagenesis in pikromycin PKS modules [35] | Altered macrolactone core structure |

| Non-natural Starter | 3-Hydroxybenzoic acid | Hybrid PKS construction with updated module boundaries [37] | Generation of a combinatorial library of novel molecules |

Combinatorial Biosynthesis and Module Engineering

Combinatorial biosynthesis applies a "plug-and-play" logic to PKS engineering, creating chimeric synthases through the exchange, insertion, or deletion of entire catalytic modules [35] [37]. The success of this strategy is highly dependent on the compatibility of the re-engineered protein interfaces.

- Updated Module Boundaries: Recent research has challenged the traditional module boundary definition (immediately upstream of the KS domain). A revised boundary situated downstream of the KS (following the AT-ACP-KS order) has demonstrated significantly higher success rates in constructing functional chimeric PKSs [37]. A large-scale study constructing 155 synthases from pikromycin PKS modules found that using the updated boundary led to the detection of anticipated products from 60% of triketide, 32% of tetraketide, and 6.4% of pentaketide synthases [37].

- Docking Domain Engineering: Efficient intermodular communication is facilitated by N- and C-terminal docking domains (NDDs and CDDs). Engineering these domains, such as using orthogonal docking motifs from the spinosyn synthase, can improve the self-assembly and activity of hybrid PKS polypeptides [37].

- Major Impediments: Despite advanced engineering, KS gatekeeping (where the KS domain selectively accepts intermediates from the previous module based on their structure) and module-skipping remain significant challenges to obtaining the intended polyketide products, especially in larger, multi-modular systems [37].

Experimental Protocols for Building Block Engineering

Protocol for High-Throughput PKS Assembly and Screening

The following methodology, adapted from a recent combinatorial study, details the construction and screening of a library of engineered PKSs [37].

- Platform Design (BioBricks-like): A cloning platform is established where DNA fragments encoding individual PKS modules, flanked by standardized restriction sites (e.g., HindIII/XbaI), are maintained on separate cloning plasmids. Each module is designed to include compatible docking domains (e.g., from the spinosyn synthase) at its termini to facilitate inter-polypeptide assembly [37].

- Sequential Ligation: The expression plasmid, containing the first and last modules of the target PKS (e.g., P1 and P7 from the pikromycin synthase), is digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes. Module-encoding DNA fragments from the cloning plasmids are then sequentially ligated into the expression vector in a predefined order to build synthases with the desired number and sequence of modules [37].

- Heterologous Expression: The constructed expression plasmids are transformed into a metabolically engineered production host, such as E. coli K207-3. This strain is engineered to heterologously express PKS proteins, activate them via phosphopantetheinylation, and supply methylmalonyl-CoA extender units [37].

- Fermentation and Metabolite Extraction: Transformed cells are cultured in shake flasks at a permissive temperature (e.g., 19°C) for an extended period (e.g., 7 days) to allow for polyketide production. Metabolites are then extracted from the culture media using ethyl acetate [37].

- Product Detection and Characterization: The extracts are analyzed by high-resolution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS). The masses of detected compounds are compared to those calculated for the anticipated products. Key metabolites are isolated and their structures are confirmed using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and crystallography [37].

Protocol for In Vivo Precursor-Directed Biosynthesis

This protocol outlines the steps for leveraging precursor pathway engineering to diversify polyketides [35] [36].

- Identify a Promiscuous Enzyme: Select a native or engineered enzyme with demonstrated promiscuity for non-natural substrates, such as a malonyl-CoA synthetase or an enoyl-thioester carboxylase/reductase (ECR) [35].

- Engineer the Host Pathway:

- Introduce the Promiscuous Enzyme: Express the gene encoding the promiscuous enzyme (e.g., the S. cinnamonensis malonyl-CoA synthetase) in the production host under a strong, inducible promoter [35].

- Modulate Native Metabolism (Optional): In some cases, it may be necessary to knockout native extender unit biosynthesis pathways or competing enzymatic activities to enhance the flux toward the desired non-natural building block [36].

- Provide Synthetic Precursors: Supplement the fermentation medium with the synthetic acid precursor corresponding to the desired extender unit (e.g., allylmalonate, propargylmalonate) [35].

- Express the Target PKS: Co-express the engineered or wild-type PKS gene cluster in the same host strain. The PKS must possess AT domains capable of recognizing and incorporating the newly generated CoA-thioesters [35] [36].

- Fermentation, Extraction, and Analysis: Cultivate the engineered strain, extract metabolites, and analyze the products using LC/MS and NMR as described in section 3.1 to identify and characterize the novel polyketide analogs [37].

Performance and Outcomes of Engineering Strategies

The success of building block engineering is quantified by the production titers of novel polyketides and the functional success rates of engineered synthases. The following table synthesizes key quantitative data from recent studies.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Polyketide Engineering Strategies

| Engineering Strategy | System/Model Used | Key Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial Biosynthesis | Pikromycin PKS modules (155 synthases) | Functional Success Rate (Triketide) | 60% | [37] |

| Functional Success Rate (Tetraketide) | 32% | [37] | ||

| Functional Success Rate (Pentaketide) | 6.4% | [37] | ||

| Reductive Loop + KR Knockout | Bimodular Lipomycin PKS | Titer of Ethyl Ketone (4,6 dimethylheptanone) | 20.6 mg/L | [36] |

| Module Boundary Comparison | Pikromycin PKS (P1-P2-P3-P4-P7) | Relative Titer (Updated vs. Traditional Boundary) | 10.4-fold higher | [37] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Polyketide Building Block Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolically Engineered Chassis | Provides essential PKS precursors (e.g., methylmalonyl-CoA) and supports heterologous expression. | E. coli K207-3 [37]; Streptomyces albus [36] |

| BioBricks-like Cloning Plasmids | Standardized vectors for rapid, sequential assembly of PKS module DNA, facilitating high-throughput combinatorial library construction. | pUC19-derived vectors with T7 promoter/terminator and docking domains [37] |

| Orthogonal Docking Domains | Engineered protein-protein interaction motifs that ensure proper assembly of hybrid PKS polypeptides from different origins. | Docking motifs from spinosyn synthase (SpnB/SpnC, SpnC/SpnD) [37] |