The Biosynthetic Logic of Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS): From Assembly Lines to Medical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the biosynthetic logic of nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), the massive enzymatic assembly lines that produce a vast array of complex natural products with...

The Biosynthetic Logic of Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS): From Assembly Lines to Medical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the biosynthetic logic of nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), the massive enzymatic assembly lines that produce a vast array of complex natural products with clinical importance. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of NRPS domains and modular organization, delves into advanced methodological and engineering approaches for novel compound discovery, addresses key challenges in troubleshooting and optimization, and discusses rigorous validation and comparative analysis techniques. By synthesizing the latest research, this review aims to bridge fundamental enzymology with applied synthetic biology, highlighting pathways for developing new therapeutic agents against pressing global threats like antimicrobial resistance.

Decoding the NRPS Assembly Line: Domains, Modules, and Biosynthetic Logic

The Core Mechanism of Nonribosomal Peptide Synthesis

Nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) are massive, multimodular enzyme complexes that function as molecular assembly lines to synthesize peptides independently of the ribosomal machinery [1] [2]. These systems are prevalent in bacteria and fungi and are responsible for producing a diverse array of secondary metabolites with significant pharmacological activities, including antibiotics (e.g., vancomycin, daptomycin), immunosuppressants (e.g., cyclosporine), and anticancer agents (e.g., bleomycin) [1] [3] [4]. Unlike ribosomal synthesis, which is constrained to the 20 canonical L-amino acids and operates based on mRNA templates, NRPSs utilize a template-independent, thiotemplate mechanism that enables the incorporation of a vast repertoire of over 400 distinct monomers, including D-amino acids, non-proteinogenic amino acids, fatty acids, and hydroxy acids [3] [2]. This fundamental difference underpins the ability of NRPSs to generate structurally complex peptides with unique chemical properties and potent bioactivities that are inaccessible through ribosomal pathways [2].

The biosynthesis initiated by NRPSs proceeds in an N- to C-terminal direction, typically producing peptides between 3 and 15 amino acids in length [1]. The primary peptide products can be linear, cyclic, or branched-cyclic, and they often undergo further post-synthetic modifications—such as methylation, glycosylation, hydroxylation, acylation, or halogenation—by dedicated tailoring enzymes to achieve their mature, biologically active forms [1] [4]. This extensive chemical diversification contributes to the broad spectrum of biological activities observed in nonribosomal peptides (NRPs) [1].

The NRPS Assembly Line: Modular Organization and Domain Functions

The NRPS assembly line is organized into sequential modules, each responsible for incorporating a single monomeric building block into the growing peptide chain [2]. Each module is further subdivided into catalytic domains that perform discrete steps in the elongation cycle. A minimal elongation module comprises three core domains: Condensation (C), Adenylation (A), and Thiolation (T) [1] [2]. The order of these modules generally collates with the sequence of the final peptide product [1].

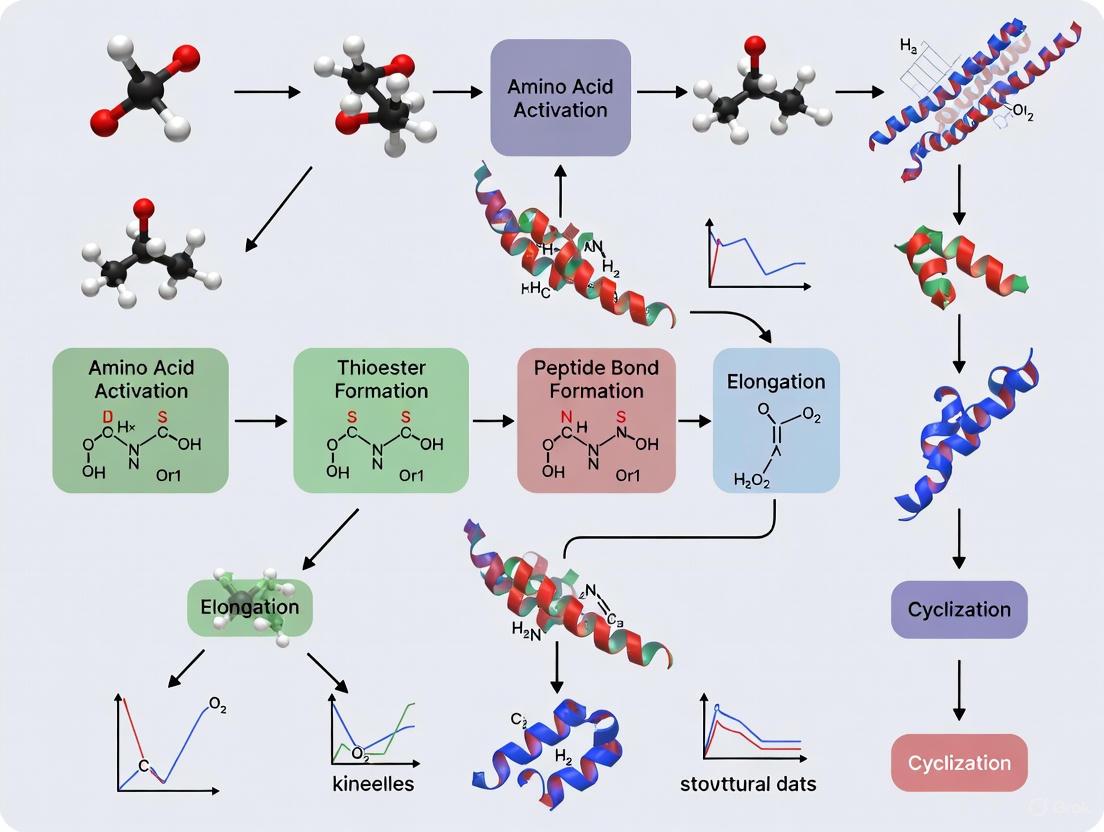

The following diagram illustrates the core domains and the linear flow of the NRPS assembly line:

The table below summarizes the core and common auxiliary domains within NRPS modules, detailing their specific functions and molecular mechanisms:

| Domain | Size (approx.) | Primary Function | Molecular Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenylation (A) | 550 amino acids [1] | Selects and activates the amino acid substrate [2] | Uses Mg-ATP to form an aminoacyl-adenylate intermediate [1] |

| Thiolation (T)/PCP | 80 amino acids [1] | Shuttles activated substrates and intermediates [2] | Covalently binds intermediates via a thioester bond to a 4'-phosphopantetheine (PP) arm [1] |

| Condensation (C) | 450 amino acids [1] | Catalyzes peptide bond formation [1] | Mediates nucleophilic attack by the downstream amino acid on the upstream thioester [2] |

| Thioesterase (TE) | 30 kDa [2] | Releases the full-length peptide from the NRPS [2] | Hydrolysis or macrocyclization [1] [2] |

| Epimerization (E) | 50 kDa [2] | Converts L-amino acids to their D-form [2] | Epimerization of the amino acid attached to the PCP domain [2] |

| Heterocyclization (Cy) | Not Specified | Forms thiazoline or oxazoline rings from Cys/Ser/Thr residues [4] | Catalyzes cyclization and subsequent dehydration [4] |

Table 1: Core and common auxiliary domains in NRPS modules. PCP: Peptidyl Carrier Protein.

Before an NRPS can initiate synthesis, a crucial activation step is required. Phosphopantetheinyl transferases (PPTases) post-translationally modify the T domains by attaching a 4'-phosphopantetheine prosthetic group, converting them from their inactive "apo" forms to active "holo" forms [2]. This modification provides the flexible Ppant arm that acts as a swinging arm to covalently tether and shuttle intermediates between catalytic domains [2].

Engineering the NRPS Assembly Line

The modular architecture of NRPSs suggests a compelling potential for bioengineering—swapping domains or modules like building blocks to create novel assembly lines that produce custom peptides [2]. However, this engineering endeavor faces significant challenges. NRPSs are highly interdependent systems, and simply swapping fragments at random junctions often disrupts crucial protein-protein interactions, leading to non-functional enzymes or dramatically reduced product yields [5] [2]. A primary obstacle is the incompatibility between parts from different NRPS systems, which can result in impaired catalytic activity or the production of unintended side products [5].

Advanced Strategies for NRPS Engineering

To overcome these challenges, researchers have developed sophisticated strategies based on the concept of eXchange Units (XUs), which are conserved motifs located within or between domains that serve as reliable "split sites" for recombination [2]. These strategies aim to preserve the natural interfaces and "handshake" between functional units, thereby improving the compatibility and success rate of generating functional chimeric NRPSs [2].

The following workflow visualizes the decision process for selecting an appropriate NRPS engineering strategy:

The table below compares the primary XU strategies developed for NRPS engineering:

| Strategy | Split Site Location | Key Advantages | Potential Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| XU | C-A interface (within WNATE motif) [2] | Enables modular recombination while preserving domain specificity [2] | Often results in reduced production titers [2] |

| XUC | Inside the C domain [2] | Significantly higher product yields; reduces diversity of side products [2] | Less flexible for single-domain swaps [2] |

| XUTI | Linker region between A-T domains [2] | Broad applicability across diverse NRPSs; preserves intact T domain and its interaction with the downstream C domain [2] | Incompatibilities may still arise at inter-module interfaces (e.g., upstream A to downstream T) [2] |

| XUTIV | Inside the T domain [2] | Inspired by natural evolutionary recombination; allows assembly of fragments from highly diverse sources [2] | Risk of incompatibility within the T domain itself [2] |

Table 2: Comparison of eXchange Unit (XU) strategies for NRPS engineering.

A recent pioneering example of NRPS engineering involved the repurposing of a termination module responsible for adding a C-terminal putrescine moiety to glidonins, a class of dodecapeptides [6]. Researchers successfully swapped this unusual termination module into two other NRPS systems, which led to the addition of putrescine to the C-terminus of the resulting peptides. This modification improved the hydrophilicity and bioactivity of the engineered products, demonstrating the potential of module swapping for generating novel and improved nonribosomal peptides [6].

Experimental and Computational Toolkit for NRPS Research

Key Experimental Protocols and Reagents

Elucidating the biosynthetic logic of NRPSs and engineering new pathways requires a combination of robust experimental protocols. The following table lists essential reagents and materials used in key experiments within the field:

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in NRPS Research |

|---|---|

| Redαβ7029 Recombineering System | An efficient genetic tool used for in-situ promoter insertion to activate silent NRPS gene clusters in native producers like Schlegelella brevitalea and for targeted gene inactivation [6]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing | Enables precise domain inactivation within NRPS genes in the native host organism (e.g., point mutations in TE, C, or A domains) to map biosynthetic steps and characterize intermediates [7]. |

| Heterologous Expression Hosts | Chassis organisms (e.g., E. coli) used to express entire NRPS gene clusters from difficult-to-manipulate native producers, facilitating product isolation and pathway characterization [8]. |

| High-Resolution LC-MS/MS | Used for comparative metabolomics to identify novel NRPs, characterize their structures, and detect biosynthetic intermediates that accumulate in engineered or mutant strains [7] [6]. |

| 4'-Phosphopantetheinyl Transferase (PPTase) | Essential post-translational activation reagent that converts inactive apo-NRPSs into their active holo-forms by installing the phosphopantetheine cofactor on T domains [1] [2]. |

| Glepidotin B | Glepidotin B, CAS:87440-56-0, MF:C20H20O5, MW:340.4 g/mol |

| BTA-2 | BTA-2, CAS:10205-62-6, MF:C16H16N2S, MW:268.4 g/mol |

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for NRPS experimentation.

A critical protocol for functional characterization involves domain inactivation via genome editing followed by comparative metabolomics [7]. This methodology can be broken down into the following steps:

- Design and Introduction of Mutations: Use CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce specific point mutations into the target NRPS gene within the native producer organism. The mutations are designed to alter key catalytic residues in a specific domain (e.g., replacing the active-site serine in a TE domain with alanine) [7].

- Cultivation and Metabolite Extraction: Grow the mutant strain under appropriate fermentation conditions alongside a wild-type control. Harvest cells and extract metabolites using standard organic solvents [7] [6].

- Metabolite Analysis via LC-MS: Analyze the crude extracts using high-resolution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Compare the chromatograms and mass spectra of the mutant and wild-type strains to identify the absence of the final product and the potential accumulation of biosynthetic intermediates [7].

- Intermediate Purification and Structure Elucidation: For conclusive identification, scale up the culture of the mutant strain. Purify the accumulated intermediates through multiple chromatographic steps (e.g., HPLC). Elucidate their structures using advanced techniques such as NMR spectroscopy and MS/MS fragmentation [7] [6].

Computational Tools for Pathway Prediction and Engineering

Computational tools are increasingly vital for navigating the complexity of NRPS systems, from predicting the function of enigmatic domains to planning the engineering of new pathways.

- BioNavi-NP: A deep learning-driven toolkit that predicts biosynthetic pathways for natural products via bio-retrosynthesis [9]. It uses transformer neural networks trained on biochemical and organic reactions to propose plausible precursor molecules for a target compound. Its AND-OR tree-based planning algorithm can then map multi-step pathways from simple building blocks to the complex target NP, achieving a high success rate in recovering known building blocks [9]. This is particularly useful for elucidating or reconstructing pathways for NRPs of unknown biogenesis.

- Phylogenetic Analysis for Engineering: Computational phylogenetics can analyze the evolutionary relationships between NRPS domains and modules. This analysis helps predict the compatibility between units from different NRPS systems, guiding the pre-selection of functional combinations for engineering and increasing the success rate of generating active chimeric assembly lines [2].

- Specificity Predicting Tools: Online tools and algorithms (e.g., based on the signature sequences of A domains, known as Stachelhaus codes) can predict the substrate specificity of A domains from genomic sequence data, providing a preliminary blueprint of the peptide structure encoded by an NRPS gene cluster [1] [6].

Nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) are monumental enzymatic assembly lines responsible for the biosynthesis of a vast array of complex peptide natural products with potent biological activities, including many essential pharmaceuticals. The biosynthetic logic of these systems is governed by a modular, assembly-line architecture where each module, responsible for incorporating a single monomeric unit, contains core catalytic domains that perform sequential activation, carrier, and condensation functions. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the three core domains—the Adenylation (A) domain, the Thiolation/Peptidyl Carrier Protein (T/PCP) domain, and the Condensation (C) domain. We summarize their precise molecular mechanisms, structural characteristics, and intricate functional coordination, which together determine the sequence and structure of the final peptide product. Framed within the context of biosynthetic engineering, this review also details contemporary experimental methodologies and reagents essential for probing NRPS function, aiming to equip researchers with the tools to harness and reprogram these machineries for the synthetic biology-driven discovery of novel bioactive compounds.

Nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) are multimodular megaenzymes that catalyze the synthesis of a wide spectrum of peptide-based natural products without the direct template of mRNA [10] [11]. These peptides, such as the antibiotic daptomycin and the immunosuppressant cyclosporin A, are notable for their structural complexity, which arises from the incorporation of non-proteinogenic amino acids, D-amino acids, and various heterocyclic rings, as well as tailoring modifications like N-methylation and glycosylation [10]. The pharmaceutical relevance of these compounds has driven extensive research into the fundamental principles of their biosynthesis.

The foundational logic of NRPSs is their modular and assembly-line-like organization. A single module is typically responsible for the incorporation of one building block into the growing peptide chain [10] [12]. A minimal elongation module comprises three core catalytic domains that perform a coordinated sequence of operations:

- Adenylation (A) Domain: Selects and activates a specific amino acid substrate.

- Thiolation/Peptidyl Carrier Protein (T/PCP) Domain: Shuttles the activated substrate and the growing peptide chain between catalytic domains.

- Condensation (C) Domain: Catalyzes peptide bond formation between adjacent building blocks.

The initiation module of an NRPS pathway lacks a C domain, while the termination module features a specialized domain such as a Thioesterase (TE) or Reductase (R) domain to release the fully assembled product [10] [11]. The following sections delve into the structure, function, and mechanistic details of each core domain, providing a comprehensive guide to the biosynthetic logic of these complex molecular machines.

The Adenylation (A) Domain: The Gatekeeper of Specificity

Structure and Catalytic Mechanism

The A domain is the primary determinant of substrate specificity in NRPS assembly lines. It is a ~550 residue domain belonging to the adenylate-forming enzyme superfamily, which also includes firefly luciferase [12]. Structurally, it is composed of a large N-terminal subdomain (Acore, residues ~1-400) and a smaller C-terminal subdomain (Asub, residues ~500-550) [12] [13]. The active site, located at the interface of these two subdomains, features conserved signature sequences designated A1 through A10 [12].

The A domain catalyzes a two-step reaction through a Bi Uni Uni Bi ping-pong mechanism:

- Adenylation: The A domain recognizes its specific amino acid substrate and, in an ATP-dependent reaction, activates it to form an aminoacyl-adenylate (aminoacyl-AMP) intermediate, releasing inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi).

- Thioesterification: The aminoacyl moiety is subsequently transferred from the adenylate to the thiol of the 4'-phosphopantetheine (PPant) arm, which is covalently attached to the adjacent PCP domain. This forms a stable thioester linkage [12].

A critical feature of this mechanism is domain alternation. After the adenylation step, the Asub domain undergoes a ~140° rotation relative to the Acore domain. This dramatic conformational change reorients the active site, ejecting the spent AMP and creating a new binding surface to accommodate the incoming PCP domain for the thioesterification step [12].

Substrate Selection and Engineering

The A domain contains a dedicated substrate specificity pocket within the Acore subdomain that sterically and chemically defines which amino acid it activates [10]. Ten key residues within this pocket, known as the "nonribosomal code," have been identified as primary determinants of substrate selection [11]. This knowledge enables bioinformatic prediction of incorporated substrates from gene sequences using tools like NRPSpredictor2 [11] and facilitates rational engineering efforts. By mutating these specificity-conferring residues, researchers have successfully altered the substrate selectivity of A domains, a cornerstone strategy for generating novel "non-natural" natural products through pathway engineering [10] [11].

Table 1: Key Structural and Functional Features of the Core NRPS Domains

| Domain | Core Function | Key Structural Motifs | Essential Cofactors/ Ligands | Catalytic Steps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenylation (A) | Substrate activation | A1-A10 motifs; Substrate specificity pocket | ATP, Mg²âº, Amino Acid | 1. Adenylation (aminoacyl-AMP formation)2. Thioesterification (loading onto PCP) |

| Thiolation/Peptidyl Carrier Protein (T/PCP) | Substrate/ intermediate shuttling | 4-helix bundle; Conserved serine residue | Coenzyme A (for PPant post-translational modification) | Covalent tethering of substrates via thioester bond |

| Condensation (C) | Peptide bond formation | HHxxxDG catalytic motif; Donor & Acceptor Tunnels | None (catalyzes nucleophilic attack) | Amide bond formation between PCP-bound donors and acceptors |

The Thiolation/Peptidyl Carrier Protein (T/PCP) Domain: The Molecular Shuttle

Structure and Post-Translational Modification

The T/PCP domain is a small, ~80-100 amino acid domain that serves as a flexible swing arm, tethering the growing peptide chain and shuttling intermediates between the catalytic centers of the NRPS module [10] [12]. Its structure is characterized by a compact, four-helix bundle fold [14] [12]. A conserved serine residue, located at the beginning of the second helix, is the site for an essential post-translational modification catalyzed by a phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) [10] [12]. The PPTase attaches the 4'-phosphopantetheine (PPant) moiety derived from coenzyme A to this serine, converting the inactive "apo" form of the PCP to the active "holo" form [12]. The terminal thiol of this PPant arm serves as the covalent attachment point for all amino acid and peptidyl intermediates during synthesis.

Conformational Dynamics and Partner Domain Interactions

The PCP domain does not operate in isolation; its function is defined by its interactions with other catalytic domains. Structural studies, including NMR and X-ray crystallography, reveal that the PCP domain utilizes a hydrophobic patch surrounding the PPant-attachment site to dock with its partner domains, such as the A and C domains [12] [15]. These interactions are dynamic and are believed to be guided by the PCP's conformational flexibility, which allows it to present its cargo to the correct active site at the appropriate time in the catalytic cycle [14] [12]. The functional interplay between the PCP and its partner domains is a critical area of research, as improper PCP-domain interactions are a major hurdle in the engineering of functional hybrid NRPSs [10].

The Condensation (C) Domain: The Peptide Bond Architect

Structure and Catalytic Motif

The C domain is responsible for the central chemical step in NRP synthesis: the formation of the peptide bond. It is a ~450 residue domain that adopts a pseudo-dimeric fold, with each half resembling the structure of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) [15] [16]. The two subdomains create a V-shaped active site cleft with two distinct substrate-access tunnels: one for the donor substrate (the upstream peptidyl-S-PCP) and one for the acceptor substrate (the downstream aminoacyl-S-PCP) [15].

At the heart of the C domain active site lies the universally conserved HHxxxDG motif [15] [16]. The first histidine residue of this motif is generally considered the primary catalytic base, responsible for deprotonating the α-amino group of the acceptor substrate, thereby enhancing its nucleophilicity for attack on the thioester carbonyl carbon of the donor substrate [15] [16].

Acceptor Substrate Selectivity and Gatekeeping

While A domains are the primary arbiters of substrate selection, C domains also exhibit significant acceptor substrate selectivity, which is crucial for ensuring the correct order of amino acid incorporation [15]. Structural studies of a C domain in complex with an aminoacyl-PCP acceptor substrate have illuminated the mechanism behind this selectivity. The interface is predominantly hydrophobic, and access to the active site is controlled by a "gatekeeping" arginine residue [15]. This residue is thought to prevent unloaded or incorrectly loaded PCPs from entering the acceptor tunnel, thereby acting as a checkpoint for fidelity [15].

Furthermore, recent research has revealed that C domains can possess specialized functions beyond standard peptide bond formation. These include epimerization (E) activities, where the C domain works in concert with a dedicated E domain to control stereochemistry, and heterocyclization (Cy) activities, where the C domain catalyzes both peptide bond formation and the subsequent cyclization of Cys, Ser, or Thr residues to form thiazoline or oxazoline rings [10] [16].

Figure 1: The Catalytic Cycle of a Minimal NRPS Elongation Module. The core domains work in concert: the A domain activates and loads a building block onto the PCP domain; the PCP domain shuttles the cargo to the C domain, which catalyzes peptide bond formation with the upstream peptide chain.

Coordination Between Core Domains: The RXGR Motif and Structural Dynamics

The high efficiency of NRPSs relies on the precise coordination between the A, PCP, and C domains, minimizing the diffusion of intermediates and ensuring catalytic fidelity. Recent structural biology breakthroughs have provided molecular insights into this coordination. A key discovery is the role of a conserved RXGR motif located in the C domain [13].

This motif mediates a dynamic interaction with the A domain of the same module. The substrate-induced rotation of the A domain's Asub subdomain is guided by its interaction with the C domain via the RXGR motif. This interaction enhances the adenylation activity of the A domain by stabilizing a more efficient state transition [13]. When this interaction is disrupted, the Asub domain rotates randomly, leading to significantly reduced adenylation efficiency. This reveals a previously underappreciated mechanism where the C domain allosterically assists its cognate A domain in substrate selection and activation, ensuring the rapid and correct loading of the PCP domain to fuel the assembly line [13].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Core Domains

Structural Elucidation Methodologies

Understanding the structure-function relationships of NRPS domains has been propelled by techniques like X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy.

- Protein Engineering for Crystallography: A common strategy involves dissecting the mega-enzyme into single domains or stable didomain constructs (e.g., A-PCP, PCP-C, C-A) with carefully chosen domain boundaries [12] [15]. For instance, the structure of the fuscachelin PCP2-C3 didomain was solved by expressing this discrete construct, which yielded stable, crystallizable protein [15].

- Trapping Transient Complexes: Capturing the transient interaction between a PCP and its partner catalytic domain is challenging. This has been achieved using mechanism-based inhibitors, such as fluorophosphonates and aminophosphates, which form stable covalent mimics of the reaction intermediates (e.g., acyl-enzymes or tetrahedral intermediates) [12] [17]. For example, a fluorophosphonate analog of nocardicin G was used to trap and solve the structure of the thioesterase domain in a substrate-bound state [17].

- Solution-State Studies with NMR: NMR is particularly valuable for studying the dynamics of individual domains like the PCP, which sample multiple conformations in solution. NMR structures of PCP domains in both apo and holo forms have provided critical insights into the conformational flexibility that enables their shuttling function [14] [12].

Functional and Biochemical Assays

- Adenylation Activity (ATP-PPi Exchange Assay): This classic assay quantifies the first half-reaction of the A domain. It measures the A domain's ability to catalyze the ATP-dependent formation of an aminoacyl-adenylate by tracking the incorporation of radioactively labeled PPi back into ATP. The rate of this exchange is proportional to the A domain's activity and specificity for a given amino acid substrate [12].

- Holoprotein Formation and Loading Assay: The activity of the PPTase and the subsequent loading of the amino acid onto the holo-PCP can be monitored using radioactively labeled substrates (e.g., ³H- or ¹â´C-amino acids) or by mass spectrometry. Following the covalent attachment of the radiolabeled amino acid to the PCP domain via gel electrophoresis or HPLC confirms successful priming and loading [12].

- Condensation Activity Assays: C domain activity is typically assayed in reconstituted systems containing the donor peptidyl-S-PCP (or mimic), the acceptor aminoacyl-S-PCP (or mimic), and the C domain. Product formation is analyzed by HPLC or LC-MS. Using stable PCP-domain mimics, such as acyl-N-acetylcysteamine (SNAC) thioesters, simplifies these assays by providing soluble, small-molecule surrogates for the PCP-bound substrates [17].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for NRPS Domain Analysis

| Reagent / Method | Function / Application | Technical Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Domain Constructs (e.g., A-PCP, C-A) | Enables structural and biochemical studies of discrete functional units. | Constructs are designed based on bioinformatic analysis of domain boundaries and linker regions to ensure proper folding and activity [15]. |

| Mechanism-Based Inhibitors (e.g., Fluorophosphonates) | Traps catalytic domains in a specific, substrate-bound state for crystallography. | Forms a stable covalent complex with the active site serine (e.g., in TE domains), mimicking the tetrahedral intermediate of the hydrolysis reaction [17]. |

| S-N-acetylcysteamine (SNAC) Thioesters | Soluble, small-molecule mimics of PCP-bound substrates. | Used in in vitro assays to study the activity of C, TE, and other domains without the need for full-length, difficult-to-express PCP proteins [17]. |

| ATP-PPi Exchange Assay | Quantifies the substrate specificity and catalytic activity of Adenylation (A) domains. | A radioactive or colorimetric/microplate-based version of this assay is a standard tool for characterizing A domain function and engineering altered specificities [12]. |

| Phosphopantetheinyl Transferase (PPTase) | Converts inactive apo-PCP domains to active holo-PCP domains in vitro. | An essential reagent for in vitro reconstitution experiments. Coexpression of a PPTase is also required for functional NRPS expression in heterologous hosts like E. coli [12]. |

The core A, T/PCP, and C domains form the foundational machinery of the nonribosomal peptide assembly line, operating through a highly coordinated and dynamic biosynthetic logic. The A domain serves as the specificity gatekeeper, the PCP domain as the indispensable molecular shuttle, and the C domain as the peptide bond-forming architect. Recent structural biology breakthroughs, such as the elucidation of the RXGR-mediated C-A domain interaction and the structures of PCP-acceptor complexes with C domains, have profoundly deepened our understanding of the allosteric regulation and selectivity mechanisms that govern these systems [15] [13].

This advanced knowledge is critical for overcoming the historical challenges in NRPS engineering, such as poor yield and incorrect processing in hybrid systems. As the structural and functional data continue to accumulate, the rational design and reprogramming of NRPSs become increasingly feasible. The continued development of robust experimental tools—including high-throughput methods for characterizing domain specificity, advanced computational modeling for predicting domain interactions, and CRISPR-based tools for precise genome editing in native producers—will empower scientists to more effectively harness these enzymatic assembly lines. The ultimate goal is to reliably expand the chemical diversity of nonribosomal peptides, opening new avenues for the discovery and development of next-generation therapeutics to address pressing medical needs.

The multiple carrier model of nonribosomal peptide synthesis represents a fundamental paradigm in secondary metabolite biosynthesis, describing a modular, assembly-line process where dedicated carrier proteins shuttle substrates and intermediates between catalytic domains. This mechanistic framework explains how large, multifunctional enzyme complexes known as nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) produce an enormous diversity of structurally and functionally complex peptides, including many clinically essential pharmaceuticals. Unlike ribosomal peptide synthesis, this model enables the incorporation of non-proteinogenic amino acids and facilitates extensive structural tailoring, creating natural products with optimized bioactive properties. This technical guide examines the core principles of the multiple carrier model, its structural basis, and the experimental methodologies driving both fundamental understanding and engineering applications in drug discovery.

Nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) are massive, multi-domain enzymatic assembly lines responsible for producing a vast array of biologically active peptide natural products. These secondary metabolites include critically important drugs such as penicillin (antibiotic), cyclosporine (immunosuppressant), and vancomycin (antibiotic) [18] [19]. The biosynthetic logic of NRPS systems contrasts sharply with ribosomal protein synthesis. Rather than relying on messenger RNA templates and the ribosome, NRPSs utilize a modular architecture where each module is responsible for incorporating a single building block into the growing peptide chain [18] [20]. This template-free strategy allows for the incorporation of hundreds of different amino acid precursors, including D-amino acids, fatty acids, and hydroxy acids, vastly expanding the chemical diversity of the final products [20].

The multiple carrier model, first explicitly named and substantiated in 1996, provides the mechanistic foundation for understanding this assembly line process [21]. It superseded the earlier "thiotemplate mechanism," which proposed a single, shared carrier cofactor for the entire enzyme complex. The key distinction of the multiple carrier model is its assertion that each amino acid-activating module within the NRPS contains its own 4'-phosphopantetheine (4'-Ppant) cofactor, forming independent thioester binding sites for amino acid substrates and the elongating peptide chain [21] [18]. This architecture eliminates the need for transthiolation reactions between modules and allows the growing peptide to be passed sequentially from one carrier protein to the next in a coordinated, directional manner.

Historical Development and Mechanistic Evolution

The conceptual journey to the multiple carrier model began with observations that the biosynthesis of peptides like gramicidin S and tyrocidine was unaffected by ribosome-targeting inhibitors, indicating a template-independent pathway [18]. Fritz Lipmann and colleagues played a pivotal role in the early 1960s and 1970s by demonstrating that amino acid incorporation was ATP-dependent and that the growing peptide chain remained covalently tethered to the enzyme throughout synthesis [18].

A critical breakthrough was the identification of the 4'-phosphopantetheine (4'-Ppant) cofactor, derived from coenzyme A, as the covalent attachment point for substrates [18]. Early hypotheses suggested a single 4'-Ppant might service the entire enzyme. However, protein sequencing data later revealed a correlation of approximately 70-75 kDa of protein per amino acid activated, hinting at a modular organization [18]. This led to the initial "thiotemplate mechanism," which involved a complex series of transthiolation reactions between cysteine thiols and a single, shared 4'-Ppant cofactor.

The definitive shift to the multiple carrier model came from affinity-labeling and peptide-mapping studies on gramicidin S synthetase. These experiments demonstrated that each of the five thiolation centers in the enzyme system possessed its own 4'-Ppant cofactor attached to a conserved serine residue within a specific thiolation motif (LGG(H/D)S(L/I)) [21]. This finding was consistent with emerging genetic data showing repeating sequences in NRPS genes equivalent to the number of activated amino acids, solidifying the model of a modular, multiple-carrier system where each module operates with its own dedicated carrier protein [18].

Table 1: Evolution of NRPS Mechanistic Models

| Model | Key Feature | Carrier Cofactor Usage | Key Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thiotemplate Mechanism | Single shared carrier; transthiolation reactions between cysteine thiols and one 4'-Ppant | One cofactor per synthetase | Insensitivity to ribosome inhibitors; covalent tethering of intermediates; initial biochemical characterization [18] |

| Multiple Carrier Model | Dedicated carrier domain per module; sequential peptide elongation without transthiolation | One 4'-Ppant cofactor per activation module | Affinity labeling of all thiolation centers; CNBr/protease digestion and peptide isolation; genetic sequencing revealing repeating domains [21] [18] |

Core Domains and the Stepwise Elongation Mechanism

The multiple carrier model is operationalized through the coordinated activity of core catalytic domains organized into modules. A minimal initiation module contains an adenylation (A) domain and a peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) domain, while each elongation module contains, at a minimum, a condensation (C) domain, an A domain, and a PCP domain. A termination module concludes with a thioesterase (TE) or reductase (R) domain [12] [20].

The Core Catalytic Domains

Adenylation (A) Domain: The A domain is responsible for substrate selection and activation. It catalyzes a two-step reaction: first, it recognizes a specific amino acid and reacts it with ATP to form an aminoacyl-adenylate (aminoacyl-AMP), releasing pyrophosphate (PPi); second, it transfers the aminoacyl moiety to the thiol of the 4'-Ppant cofactor attached to the associated PCP domain, forming a covalent aminoacyl-thioester and releasing AMP [12] [18]. The A domain belongs to the adenylate-forming enzyme superfamily and undergoes a large conformational change, described as "domain alternation," between the adenylate-forming and thioester-forming states [12].

Peptidyl Carrier Protein (PCP) Domain: The PCP domain is a small, four-helix bundle protein (70-90 amino acids) that serves as the mobile shuttle of the assembly line [12] [22]. A conserved serine residue is post-translationally modified by a phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) to attach the 4'-Ppant prosthetic group. The thiol terminus of this swinging arm covalently binds the amino acid and peptide intermediates as thioesters. The PCP delivers its cargo to the various catalytic domains within its module [12].

Condensation (C) Domain: The C domain catalyzes the central reaction of peptide elongation: the formation of the peptide bond. It is a ~450 amino acid V-shaped pseudodimer [12] [20]. The C domain facilitates the nucleophilic attack of the amino group from the downstream (acceptor) PCP-bound aminoacyl-thioester on the carbonyl carbon of the upstream (donor) PCP-bound peptidyl-thioester. This results in the transfer of the growing peptide chain to the downstream PCP, elongating it by one residue [12] [23].

Thioesterase (TE) Domain: The TE domain is typically found in the termination module and catalyzes the release of the full-length peptide from the final PCP domain. This often occurs through hydrolysis (producing a linear peptide) or, more commonly, intramolecular cyclization to form macrocyclic lactones or lactams [12] [20].

The Stepwise Elongation Cycle

The following diagram illustrates the core cycle of the multiple carrier model for a single elongation module.

The elongation cycle proceeds as follows:

- Loading (A Domain Activity): The A domain in the elongation module activates its cognate amino acid and loads it onto its associated PCP domain, forming an aminoacyl-S-PCP thioester [12] [18].

- Carrier Translocation: The upstream module's PCP domain is loaded with the growing peptidyl-S-PCP chain (n residues long). Both the upstream (donor) and the current (acceptor) PCP domains translocate and dock at the condensation (C) domain of the current module [12] [20].

- Peptide Bond Formation (C Domain Activity): The C domain catalyzes nucleophilic attack by the primary amine of the aminoacyl-S-PCP (acceptor) on the carbonyl of the peptidyl-S-PCP (donor). This transpeptidation reaction forms a new peptide bond, resulting in an elongated peptidyl-S-PCP (n+1 residues) attached to the current module's carrier protein. The upstream PCP is left as a vacant holo-protein [12] [23].

- Chain Translocation: The cycle repeats as the newly elongated peptidyl-S-PCP is now the donor substrate for the C domain of the next downstream module. This process continues until the complete peptide is assembled and delivered to the termination module [20].

Table 2: Core NRPS Domains and Their Functions in the Multiple Carrier Model

| Domain | Size & Key Features | Catalytic Function | Key Motifs/Structures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenylation (A) | ~500 aa; Two subdomains (N & C-terminal); "Domain alternation" [12] | Selects/activates amino acid; Forms aminoacyl-AMP; Thioesterifies PCP [12] [18] | A1-A10 core motifs for ATP & substrate binding [12] |

| Peptidyl Carrier Protein (PCP) | ~80 aa; 4-helix bundle; Post-translational modification site [12] [22] | Shuttles covalently-bound substrates/peptides between catalytic domains [12] | Conserved serine for 4'-Ppant attachment; LGG(H/D)S(I/L) motif [21] [12] |

| Condensation (C) | ~450 aa; V-shaped pseudodimer; Active site tunnel [12] [20] | Catalyzes peptide bond formation between donor and acceptor PCP-bound thioesters [12] [23] | Donor and acceptor PCP binding sites; HHxxxDG motif often associated [20] |

| Thioesterase (TE) | ~275 aa; α/β-hydrolase fold; Variable lid region [12] [20] | Releases full-length peptide from terminal PCP via hydrolysis or cyclization [12] | Catalytic triad (Ser-His-Asp); Oxyanion hole [20] |

Structural Biology and Conformational Dynamics

The functional reality of the multiple carrier model hinges on extensive conformational dynamics. Structural biology has been instrumental in visualizing these complex enzymes, revealing how carrier proteins interact with catalytic domains and how linkers facilitate communication.

The PCP domain is the workhorse of the carrier model. NMR and crystal structures show it is an oblong four-helix bundle, with the 4'-Ppant cofactor attached to a conserved serine at the N-terminus of helix α2 [12] [22]. This location allows the PCP to present its covalently attached cargo to the active sites of partner domains. NMR studies of PCP domains, including those with their native linker regions, reveal that these domains are not static. They exhibit dynamics on fast (ps-ns) timescales, particularly in the loops and the region surrounding the active serine, which is likely necessary for the many molecular interactions and transformations it must undergo [22]. Furthermore, the unstructured linker regions flanking the PCP are not merely passive tethers. The N-terminal linker, in particular, can interact with the PCP core, stabilizing the folded state and modulating dynamics at sites involved in partner domain interactions, suggesting a role for allosteric communication within the NRPS [22].

Structures of multi-domain complexes provide snapshots of the carrier model in action. For instance, the structure of the SrfA-C termination module (C-A-PCP-TE) from surfactin synthetase revealed large distances between active sites, confirming that substantial conformational changes are required for the PCP to visit each domain [12] [20]. More recently, innovative techniques like crosslinking have been used to trap transient states, such as the peptide condensation step between two modules, allowing visualization by electron microscopy and providing unprecedented insight into how these dynamic proteins coordinate their activities [19].

Experimental Methodologies and Research Toolkit

Studying the complex dynamics and specificity of NRPSs requires a sophisticated toolkit of biochemical, structural, and engineering techniques. The following workflow and associated reagent table outline key methodologies for probing the multiple carrier model.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for NRPS (Multiple Carrier Model) Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Role in NRPS Research | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Sfp Phosphopantetheinyl Transferase | Converts inactive apo-PCP domains to active holo-PCP by installing the 4'-Ppant cofactor from CoA [23]. | Broad substrate specificity; Essential for in vitro reconstitution of NRPS activity; Used in chemoenzymatic loading of PCPs [23] [12]. |

| Mechanism-Based Inhibitors / Crosslinkers | Trap NRPS complexes in specific conformational states, enabling structural characterization of transient intermediates [19]. | Covalently link domains (e.g., A and PCP) or modules; Allow visualization of steps like condensation by Cryo-EM [19] [12]. |

| Yeast Surface Display | High-throughput platform for engineering NRPS domain specificity (e.g., of C domains) by linking function to cell sorting [23]. | Allows functional display of large NRPS modules; Enables FACS-based screening of mutant libraries after "click" chemistry-based product detection [23]. |

| N-glycosylation Site Mutants | Enables functional studies of NRPSs in heterologous hosts like yeast, which can add inhibitory sugar moieties [23]. | Point mutations (e.g., Asn→Gln) to disrupt glycosylation motifs; Critical for maintaining A domain activity in eukaryotic expression systems [23]. |

| Chemical Probes (e.g., Alkyne-tagged Substrates) | Facilitate detection and isolation of NRPS-bound intermediates via bioorthogonal chemistry (e.g., click chemistry with azide-fluorophores/biotin) [23]. | Allow tracking of substrate channeling and product formation without radioactive labels; Used in conjunction with yeast display and FACS [23]. |

| MMP12-IN-3 | MMP12-IN-3, MF:C20H26N2O5S, MW:406.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Methoxycinnamyl alcohol | 3-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-2-propen-1-ol|RUO | 3-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-2-propen-1-ol is a versatile RUO for fragrance synthesis, pharmaceutical research, and method development. For Research Use Only. Not for personal use. |

Key Experimental Workflows

In Vitro Reconstitution: A foundational approach involves expressing and purifying individual NRPS modules or domains. The PCP domains are converted to their active holo-form using Sfp PPTase and coenzyme A. Activity is then assayed by providing ATP, Mg²âº, and amino acid substrates, with products analyzed by HPLC or mass spectrometry. This method allows precise dissection of the kinetics and specificity of each enzymatic step [12] [18].

Yeast Display for Engineering: A powerful high-throughput method involves displaying a full NRPS module (e.g., C-A-T) on the yeast surface. An upstream donor module, provided in solution, can dock and its substrate be condensed with the acceptor substrate on the displayed module. The product, tethered to the yeast, is labeled via a bioorthogonal tag (e.g., an alkyne) and detected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). This platform allows for the screening of massive mutant libraries to reprogram A or C domain specificity [23].

Structural Characterization of Intermediates: The inherent dynamics of NRPSs make structural studies challenging. To overcome this, researchers use mechanism-based crosslinkers that trap the enzyme in a specific state, such as during condensation. These stabilized complexes can then be studied using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) or X-ray crystallography to provide atomic-level snapshots of the multiple carrier model in action [19] [12].

Engineering and Applications in Drug Discovery

The modular logic of the multiple carrier model makes NRPSs attractive targets for bioengineering to produce novel peptides with tailored properties. The primary strategies involve domain or module swapping, where A, C, or entire modules are exchanged between different NRPS systems to create hybrid assembly lines that produce chimeric peptides [23]. Additionally, reprogramming A domains via site-directed mutagenesis of their substrate-binding pockets allows for the incorporation of non-native amino acids [23].

A major recent advance is the high-throughput engineering of C domains, which have long been a bottleneck due to their complex structure and role as selectivity filters. Using the yeast display platform described above, researchers successfully reprogrammed the C domain of the surfactin termination module to accept fatty acid donors instead of its native peptidyl donor, increasing catalytic efficiency for this noncanonical substrate by >40-fold [23]. This demonstrates the potential to rationally alter the core condensation chemistry to generate entirely new peptide scaffolds.

These engineering efforts are driven by the profound medical importance of nonribosomal peptides. Understanding the multiple carrier model enables synthetic biology approaches to create new antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and anticancer agents, helping to address the growing crisis of antibiotic resistance and the constant need for new therapeutics [18] [23].

The multiple carrier model provides a comprehensive mechanistic framework for understanding the assembly-line biosynthesis of nonribosomal peptides. From its historical roots in foundational biochemistry to its modern validation through structural biology and its application in cutting-edge enzyme engineering, the model continues to guide research in the field. The precise coordination of multiple PCP domains shuttling intermediates between catalytic centers like the A and C domains represents a sophisticated solution for template-independent peptide synthesis. Ongoing research, leveraging high-throughput engineering and advanced structural techniques, continues to refine our understanding of this model, pushing the boundaries of our ability to harness and reprogram these enzymatic assembly lines for the discovery and production of novel bioactive compounds.

The modular architecture of nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), with its core adenylation (A), peptidyl carrier protein (PCP), and condensation (C) domains, functions as a molecular assembly line. However, the true chemical diversity of nonribosomal peptides (NRPs) stems from the activity of specialized auxiliary domains. These domains, which include epimerization (E), cyclization (Cy), thioesterase (TE), and reductase (R) domains, perform intricate modifications on the nascent peptide chain, profoundly influencing its final three-dimensional structure, stability, and biological activity. Understanding the precise mechanisms of these domains is not merely an academic exercise; it is a prerequisite for the rational engineering of NRPS machinery to produce novel therapeutics, a critical pursuit in the face of escalating antimicrobial resistance [24] [25]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the structure, function, and experimental investigation of these key specialized domains.

Domain Functions and Characteristics

The following table summarizes the core attributes, mechanisms, and outcomes associated with the four key specialized NRPS domains.

Table 1: Characteristics and Functions of Specialized NRPS Domains

| Domain | Primary Function | Key Catalytic Motif/Residues | Position in Module | Resulting Modification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epimerization (E) | Epimerization of the last amino acid in the growing peptide chain from L- to D-conformation [16]. | Proposed base-acid mechanism; specific residues still debated [16]. | Following a PCP domain in an elongation module [11]. | Incorporation of D-amino acids, which confers protease resistance and influences peptide conformation [11]. |

| Cyclization (Cy) | Catalyzes both peptide bond formation and the cyclization of Cys, Ser, or Thr side chains [16] [11]. | Likely a variant of the C-domain HHxxxDG motif [16]. | Replaces the C-domain in elongation modules [11]. | Formation of thiazoline (from Cys) or oxazoline (from Ser/Thr) rings; often followed by oxidation to aromatic thiazoles/oxazoles [16] [11]. |

| Thioesterase (TE) | Releases the full-length peptide from the NRPS assembly line [12] [25]. | Catalytic triad (e.g., Ser-His-Asp) [12]. | Termination module [11] [25]. | Hydrolysis (linear peptide) or macrocyclization (cyclic peptide) [12] [11]. |

| Reductase (R) | Releases the peptide by reducing the terminal thioester to an aldehyde or alcohol [11]. | NADPH-binding motif [12]. | Termination module (as an alternative to TE) [11]. | Peptide aldehydes or alcohols, which represent distinct chemical functionalities and bioactivities [12] [11]. |

Experimental Methodologies for Probing Domain Function

Elucidating the specific role of an auxiliary domain within a multi-modular NRPS requires a combination of genetic, biochemical, and analytical techniques. The workflow below outlines a general strategy for characterizing a specialized domain, from target identification to functional validation.

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Domain Characterization

Detailed Methodologies:

Domain-Targeted Mutagenesis: A primary method for establishing domain function is the creation of targeted point mutations. This involves substituting key catalytic residues (e.g., the serine in the TE domain catalytic triad or histidines in the Cy domain motif) with alanine or other non-functional amino acids [7]. The mutant NRPS gene is then expressed in a suitable host (e.g., E. coli or a native producer strain with the original gene cluster knocked out). The metabolites produced by the mutant strain are compared to those from the wild-type strain using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). The absence of the final product or the accumulation of a putative intermediate, as seen in NRPS-1 TE domain mutants [7], provides direct evidence of the domain's role.

In vitro Reconstitution with Synthetic Substrates: For a biochemical dissection of activity, individual domains or didomains (e.g., a PCP-E didomain) can be cloned and heterologously expressed. A powerful technique to bypass the A domain's specificity and study downstream domains like C, E, or Cy involves loading aminoacyl-CoA analogues directly onto the PCP domain using a promiscuous phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) like Sfp from Bacillus subtilis [26] [27]. These pre-loaded PCPs can then be incubated with the purified target domain and necessary co-factors to monitor the reaction in vitro. This approach was used to demonstrate the high stereospecificity of the acceptor site of C domains [26].

Structural Analysis via X-ray Crystallography: Determining high-resolution three-dimensional structures of domains, either alone or in complex with their substrates or partner proteins, is invaluable for understanding mechanism and specificity. Techniques involve generating truncated protein constructs with carefully considered domain boundaries and using mechanism-based inhibitors to trap transient complexes, such as those between A domains and PCPs [12]. For example, structures of condensation domains in complex with acceptor PCPs have revealed the hydrophobic nature of the PCP-C interface and identified gating residues that control substrate access to the active site [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for NRPS Specialized Domain Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| Sfp Phosphopantetheinyl Transferase | A broad-substrate PPTase used to convert apo-PCPs to holo-PCPs and to load PCPs with synthetic aminoacyl-/peptidyl-CoA substrates, enabling in vitro assays [26] [27]. |

| Aminoacyl-CoA Synthetases / Chemical Synthesis | Methods to generate stable aminoacyl-CoA or peptidyl-CoA analogs, which serve as donors for Sfp-mediated PCP loading [26]. |

| Catalytic Residue Mutants | Plasmids encoding NRPSs with point mutations in key catalytic residues (e.g., Ser→Ala in TE, His→Ala in Cy/C) are essential controls for confirming domain function via mutagenesis studies [7]. |

| Structured Domain Constructs | Cloned DNA for expressing individual domains or didomains (e.g., PCP-TE, PCP-E, Cy) with optimized boundaries for solubility, used in structural and in vitro biochemical studies [12] [15]. |

| Mechanism-Based Inhibitors | Small molecules that form covalent or highly stable intermediates with the target domain (e.g., adenylate analogs for A domains), used to trap and crystallize otherwise transient domain complexes [12]. |

| p-Hydroxyphenethyl anisate | 2-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)ethyl 4-Methoxybenzoate For Research |

| DAF-2DA | DAF-2DA, CAS:205391-02-2, MF:C24H18N2O7, MW:446.4 g/mol |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Engineering

The specialized domains of NRPSs are prime targets for combinatorial biosynthesis, an approach aimed at creating new-to-nature peptides with improved or novel pharmaceutical properties. The TE domain's capacity for macrocyclization can be harnessed to generate diverse cyclic peptide libraries, a structural class of high interest in drug discovery due to their metabolic stability and ability to target protein-protein interactions [24]. Engineering E domains or incorporating them into hybrid assembly lines allows for the programmed installation of D-amino acids, a key feature in many antibiotic peptides like penicillin and gramicidin [11] [25].

However, engineering efforts often face challenges such as low yields of the desired hybrid product. This underscores the complexity of NRPS machinery, where successful biosynthesis depends not only on the catalytic activity of individual domains but also on precise protein-protein interactions and the efficient channeling of intermediates [26] [24] [25]. A deep understanding of the structural and mechanistic principles outlined in this guide is therefore fundamental to overcoming these barriers and fully unlocking the potential of NRPS engineering for the discovery of next-generation therapeutics.

Nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) are molecular assembly lines that generate a diverse array of bioactive natural products without ribosomal instruction. These massive, multi-domain enzymes follow a precise biosynthetic logic, activating and incorporating specific amino acid and carboxylic acid building blocks into complex peptide architectures. The NRPS machinery operates through a modular organization where each "module," responsible for incorporating one building block, contains catalytic domains that activate, modify, and condense substrates in an assembly-line fashion [28] [29]. This review examines the biosynthetic logic of NRPS systems through two detailed case studies: the fimsbactin pathway from Acinetobacter baumannii and the gramillin pathway from Fusarium graminearum. By dissecting the domain organization, substrate selectivity, and unique biochemical strategies employed by these systems, we aim to illuminate the fundamental principles governing nonribosomal peptide assembly and highlight emerging engineering approaches for generating novel bioactive compounds.

Case Study 1: Fimsbactin Biosynthesis inAcinetobacter baumannii

Fimsbactin A is a mixed-ligand siderophore critical for the virulence of the multi-drug resistant pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. This structurally unusual siderophore contains phenolate-oxazoline, catechol, and hydroxamate metal-chelating groups branching from a central L-Ser tetrahedral unit via both amide and ester linkages [30]. Its biosynthesis is encoded by the fbs operon, which facilitates the conversion of simple precursors—two molecules of L-Ser, two molecules of 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB), and one molecule of L-Orn—into the final functional siderophore [30]. Fimsbactin represents a compelling NRPS target for engineering therapeutic interventions because its iron-scavenging capability is essential for bacterial survival under low-iron conditions during infection [28].

Domain Architecture and Biosynthetic Logic

The fimsbactin assembly line comprises four NRPS enzymes (FbsE, FbsF, FbsG, and FbsH) working in concert with tailoring enzymes (FbsI, FbsJ, FbsK). The biosynthetic logic follows a branched pathway rather than a linear assembly, an unusual feature in NRPS systems [28] [30].

Key Enzymes and Domains:

- FbsH: A stand-alone aryl adenylation domain that activates and loads DHB onto the N-terminal peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) of FbsE [28].

- FbsE: Contains two PCP domains (N-terminal and C-terminal) and a truncated adenylation domain. The N-terminal PCP partners with FbsH to accept the DHB moiety [28].

- FbsF: Features adenylation and PCP domains responsible for activating and loading L-Ser onto the C-terminal PCP of FbsE and the PCP of FbsG [30].

- FbsG: Contains condensation and cyclization domains that catalyze oxazoline formation and product release [30].

- FbsIJK: A set of tailoring enzymes that convert L-Orn to N1-acetyl-N1-hydroxy-putrescine (ahPutr), the hydroxamate precursor [30].

The fimsbactin pathway exemplifies a unique "branching" logic facilitated by a terminating C-T-C motif in FbsG, which enables dynamic equilibration between N-DHB-Ser and O-DHB-Ser thioester intermediates, ultimately forming both amide and ester linkages in the final product [30].

Structural Basis for Substrate Selectivity and Engineering

Recent structural studies of FbsH have provided insights into the molecular determinants of substrate selectivity. The enzyme's active site contains specific residues that form hydrogen bonds with the two hydroxyl groups of its native substrate, DHB, while hydrophobic residues create a complementary binding pocket [28]. Structures of FbsH bound to DHB and the inhibitor Sal-AMS revealed the conformational flexibility of its C-terminal subdomain, which adopts distinct orientations during the adenylate-forming and thioester-forming steps of the catalytic cycle [28].

Engineering Expanded Substrate Promiscuity: Structure-guided mutagenesis of FbsH has successfully expanded its binding pocket to accommodate DHB analogs with bulkier substituents. These engineered FbsH variants showed significantly improved activity toward non-native substrates in adenylation assays, demonstrating the potential for pathway engineering to generate novel siderophore analogs [28]. In vitro reconstitution experiments confirmed that some of these alternate substrates can progress through the entire fimsbactin assembly line, albeit with varying efficiencies, indicating that downstream domains also exert selectivity constraints [28].

Table 1: Key Catalytic Domains in Fimsbactin Biosynthesis

| Enzyme | Domain Organization | Function | Native Substrate |

|---|---|---|---|

| FbsH | A domain | Activates and adenylates aryl acid | 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) |

| FbsE | PCP(N)-A({trunc})-PCP(_C) | Carriers for aryl acid and first serine | DHB (on PCP(N)), L-Ser (on PCP(C)) |

| FbsF | A-T | Activates and loads serine | L-Serine |

| FbsG | C(1)-C(2)-Cy-T-TE | Condensation, cyclization, release | N-DHB-Ser, O-DHB-Ser, ahPutr |

| FbsIJK | Decarboxylase, Monooxygenase, Acetyltransferase | Converts L-Orn to ahPutr | L-Ornithine |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Reconstitution

In Vitro Reconstitution of Fimsbactin Biosynthesis: The complete fimsbactin biosynthesis has been successfully reconstituted in a cell-free system using purified enzymes [30]. The protocol involves:

- Enzyme Purification: Heterologous expression and purification of individual Fbs enzymes (FbsEFGH and FbsIJK).

- Substrate Preparation: Preparation of DHB, L-Ser, L-Orn, and ATP as core substrates.

- Reaction Assembly: Combining substrates and enzymes in appropriate buffer conditions with necessary cofactors (Mg(^{2+}), NADPH).

- Product Analysis: LC-MS analysis to detect fimsbactin A and intermediates.

Chemoenzymatic Production of Analogs: For producing fimsbactin analogs, the protocol can be modified:

- Alternate Substrate Screening: Incubation of FbsH with DHB analogs to assess activation efficiency.

- Partial Reconstitution: Using synthetic ahPutr with FbsEFGH to bypass the tailoring steps.

- Thioesterase Assay: Monitoring FbsM activity through detection of the shunt metabolite DHB-oxa [30].

Case Study 2: Gramillin Biosynthesis inFusarium graminearum

Gramillins A and B are bicyclic lipopeptides identified as virulence factors produced by the filamentous fungus Fusarium graminearum. These compounds possess a unique fused bicyclic structure where the main peptide macrocycle is closed via an anhydride bond—the first documented instance of such cyclization in a natural peptide [31] [29]. Gramillins display host-specific virulence, promoting fungal infection in maize but not in wheat, illustrating how pathogens can deploy specialized metabolites in a host-dependent manner [31]. Their production in planta on maize silks enhances fungal virulence, and infiltration of purified gramillins induces cell death specifically in maize leaves [31].

Domain Architecture and Biosynthetic Logic

Gramillin biosynthesis is governed by the NRPS8 gene cluster, which includes the core NRPS enzyme GRA1 and a pathway-specific transcription factor GRA2 that regulates cluster expression [31] [29]. GRA1 is a multi-modular NRPS containing seven adenylation (A) and condensation (C) domains that assemble the cyclic lipopeptide backbone through a defined sequence of catalytic events [29].

Biosynthetic Logic: The gramillin assembly line follows a linear logic initiated with either glutamic acid or 2-amino adipic acid, with subsequent modules incorporating leucine, serine, HO-glutamine, 2-amino decanoic acid, and two cysteine residues [29]. The unique anhydride bond formation occurs during the cyclization release step, creating the characteristic fused bicycle that defines the gramillin structure.

Table 2: Gramillin Structural Features and Bioactivity

| Feature | Gramillin A | Gramillin B |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Type | Bicyclic lipopeptide | Bicyclic lipopeptide |

| Cyclization | Anhydride bond | Anhydride bond |

| Biological Role | Host-specific virulence factor | Host-specific virulence factor |

| Host Specificity | Virulent in maize | Virulent in maize |

| Cellular Effect | Induces cell death in maize | Induces cell death in maize |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Elucidation

Gene Cluster Identification and Validation:

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identification of the NRPS8 cluster using antiSMASH and similar genome mining tools.

- Targeted Gene Disruption: Knockout of GRA1 and GRA2 to confirm their essential role in gramillin production.

- Heterologous Expression: Expression of cluster genes in heterologous hosts to confirm biosynthetic capability.

Structural Elucidation Protocols:

- Compound Purification: Isolation of gramillins from fungal cultures using chromatographic methods.

- NMR Analysis: Application of advanced NMR techniques including (^1)H-(^{15})N-(^{13})C HNCO and HNCA on isotopically enriched compounds to determine the bicyclic structure.

- Mass Spectrometry: High-resolution LC-MS to confirm molecular formulas and fragmentation patterns.

Comparative Biosynthetic Logic and Engineering Strategies

Domain Organization and Product Structural Diversity

Despite sharing the fundamental NRPS assembly-line logic, fimsbactin and gramillin biosynthesis employ distinct domain organizations that yield dramatically different products. The fimsbactin system utilizes a combination of stand-alone adenylation domains and multi-domain proteins with specialized termination domains that enable branched architecture formation [28] [30]. In contrast, the gramillin system employs a more conventional linear multi-modular NRPS but achieves unique cyclization through anhydride bond formation—a rare release mechanism that creates its signature bicycle [31] [29].

This comparison highlights how nature has evolved diverse solutions within the NRPS paradigm: fimsbactin exemplifies branching logic through dynamic intermediate equilibration, while gramillin demonstrates innovative release mechanisms that create constrained architectures. Both systems illustrate how module number, domain composition, and release mechanisms collectively determine final product structure.

Experimental and Engineering Frameworks

The investigation of both systems exemplifies modern approaches to elucidating and engineering NRPS logic. For fimsbactin, in vitro reconstitution has been pivotal for understanding the pathway biochemistry and enabling engineering efforts [30]. For gramillin, genetic approaches including targeted gene disruption coupled with detailed structural analysis have revealed the biosynthetic pathway [31] [29].

Emerging Engineering Strategies: Recent advances in synthetic biology offer powerful strategies for engineering NRPS systems like fimsbactin and gramillin:

- Synthetic Interface Engineering: Implementation of synthetic coiled-coils, SpyTag/SpyCatcher systems, and split inteins as orthogonal connectors to facilitate module swapping and pathway engineering [32].

- Cell-Free Biosynthesis Platforms: Utilization of cell-free expression systems for rapid prototyping of NRPS pathways and production of novel analogs [33].

- mRNA Truncation Rescue: Splitting large NRPS genes into smaller, separately translated subunits to rescue translation of truncated mRNAs, significantly improving biosynthetic efficiency as demonstrated in polyketide systems [34].

- Structure-Guided Engineering: Using structural information of adenylation domains to rationally engineer substrate specificity, as successfully demonstrated with FbsH [28].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools for NRPS Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Sal-AMS | Inhibitor of aryl adenylation domains | Structural studies of FbsH substrate binding [28] |

| Cell-free expression systems | In vitro pathway reconstitution | Fimsbactin biosynthesis from purified enzymes [33] [30] |

| Heterologous hosts (e.g., P. pastoris) | Cluster expression and validation | Expression of fgm genes for GAA biosynthesis [29] |

| AntiSMASH | Bioinformatic identification of BGCs | NRPS8 cluster identification in F. graminearum [29] |

| Isotopically labeled substrates | NMR-based structure elucidation | Structural determination of gramillins [31] |

Visualization of NRPS Biosynthetic Logic

The following diagrams illustrate key concepts in NRPS biosynthetic logic using Dot language, visualizing the fundamental domain organization and assembly line processes.

Fimsbactin Assembly Line Logic

Gramillin NRPS Assembly Line

The case studies of fimsbactin and gramillin biosynthesis exemplify the sophisticated logic embedded in NRPS assembly lines while highlighting distinct strategies for generating structural diversity. Fimsbactin demonstrates how branching architectures arise through dynamic equilibration of intermediates and specialized termination domains, while gramillin illustrates how novel release mechanisms can create constrained bicyclic scaffolds. Both systems underscore the relationship between domain organization and product structure—a fundamental principle of NRPS logic.

The experimental frameworks and engineering strategies discussed provide a roadmap for future NRPS research and applications. Structure-guided engineering of adenylation domains, combined with emerging synthetic biology tools such as synthetic interfaces and cell-free systems, offers powerful approaches for reprogramming these molecular assembly lines. As our understanding of NRPS logic deepens through continued investigation of diverse systems, the potential to harness these enzymes for generating novel bioactive compounds continues to expand, promising new avenues for therapeutic development in an era of increasing antimicrobial resistance.

Nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) are massive enzymatic assembly lines that produce a vast array of structurally complex peptides with significant pharmaceutical applications, including antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and anticancer agents [26] [35]. Unlike ribosomally synthesized peptides, NRPSs generate peptides with extraordinary structural diversity, which can be categorized into three primary architectural classes: linear, cyclic, and branched forms [26] [3]. The biosynthetic logic of NRPSs follows a modular organization where each module, typically comprising core adenylation (A), thiolation (T), and condensation (C) domains, is responsible for incorporating a specific monomeric building block into the growing peptide chain [26] [29]. This collinear arrangement between module organization and peptide sequence provides the foundational biosynthetic logic that enables the predictable engineering of novel peptide structures [26]. The remarkable architectural diversity of nonribosomal peptides stems from the intricate coordination of multifunctional domains and their tailoring enzymes, which work in concert to generate structural modifications that significantly expand the chemical space beyond what is achievable through ribosomal peptide synthesis [26] [3].

Core NRPS Domains and Their Functions in Peptide Assembly

The NRPS assembly line operates through the coordinated activity of specialized domains that activate, transport, and join monomeric building blocks. Understanding these core catalytic domains is essential for comprehending the structural diversity of the final peptide products.

Table 1: Core Catalytic Domains in NRPS Assembly Lines

| Domain | Function | Role in Peptide Architecture |

|---|---|---|

| Adenylation (A) Domain | Selects and activates amino acid substrates through adenylation | Determines monomer incorporation and side chain properties |

| Thiolation (T/PCP) Domain | Carries activated substrates on phosphopantetheine arm | Shuttles intermediates between catalytic sites |

| Condensation (C) Domain | Catalyzes peptide bond formation between donor and acceptor substrates | Controls chain elongation and stereochemistry |

| Thioesterase (TE) Domain | Releases full-length peptide from assembly line | Determines linear vs. cyclic architecture through hydrolysis or cyclization |

| Epimerization (E) Domain | Converts L-amino acids to D-amino acids | Introduces stereochemical diversity critical for bioactivity |

| Heterocyclization (Cy) Domain | Catalyzes cyclization of Cys/Ser/Thr residues | Forms thiazoline/oxazoline rings for structural complexity |

The biosynthesis begins when the A domain recognizes and activates a specific amino acid substrate through adenylation, forming an aminoacyl-AMP intermediate [26] [35]. The activated substrate is then transferred to the T domain (also called peptidyl carrier protein, PCP), which tethers it via a thioester linkage to a 4'-phosphopantetheine (Ppant) cofactor [26]. The C domain subsequently catalyzes peptide bond formation between the upstream donor substrate and the downstream acceptor substrate, resulting in peptide chain elongation [26] [23]. This process repeats along the NRPS assembly line until the complete peptide is assembled and released, typically by a TE domain that can catalyze either hydrolysis to yield linear peptides or cyclization to generate cyclic architectures [26] [29].

Figure 1: NRPS Core Domain Organization and Biosynthetic Logic

Linear Nonribosomal Peptides: Biosynthesis and Examples

Linear nonribosomal peptides represent the simplest architectural class, where amino acid monomers are joined in a sequential chain without branching or macrocyclization. These peptides are characterized by their straightforward assembly line biosynthesis and N-to-C terminal directionality.

Biosynthetic Mechanism of Linear Peptides

The biosynthesis of linear peptides follows the canonical NRPS assembly line logic, where modules activate, transport, and condense amino acids in a colinear fashion [26]. The defining feature of linear peptide biosynthesis is the final cleavage step catalyzed by the thioesterase (TE) domain, which hydrolyzes the thioester bond linking the completed peptide to the final T domain, resulting in the release of a linear peptide product [26] [29]. In some specialized cases, linear peptides undergo C-terminal functionalization, such as the addition of putrescine moieties observed in glidonins, where an unusual termination module directly catalyzes the assembly of putrescine into the peptidyl backbone [6].

Representative Linear Peptides and Functions

Table 2: Representative Linear Nonribosomal Peptides and Their Properties

| Peptide Name | Producing Organism | Amino Acid Composition | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fusaoctaxins | Fusarium graminearum | GABA/GAA initiation, 7 L/D-amino acids | Virulence factors during wheat infection |

| Gramillin | Fusarium graminearum | Glu/2-amino adipic acid, Leu, Ser, HO-Gln, 2-amino decanoic acid, 2xCys | Host-specific virulence factor |

| Glidonins | Schlegelella brevitalea | Dodecapeptides with C-terminal putrescine | Bioactivity enhanced by improved hydrophilicity |

| Viscosin | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Cyclic lipopeptide precursor | Biosurfactant properties, root colonization under drought |

Fusaoctaxins A and B exemplify linear peptides with unusual structural features. These octapeptides, produced by Fusarium graminearum, are characterized by C-terminally reduced structures rich in D-amino acid residues [29]. Their biosynthesis involves two core NRPS genes (nrps5 and nrps9) that collaborate to assemble the peptide chain, with NRPS9 serving as a load module for initiating unit binding (either γ-aminobutyric acid or guanidoacetic acid), while NRPS7 contains seven extension modules [29]. The linear peptide gramillin represents another fascinating example, featuring a unique anhydride bond involvement in its cyclization, marking the first reported occurrence of such structural feature in a cyclic peptide [29].

Cyclic Nonribosomal Peptides: Structural Diversity and Biosynthetic Logic

Cyclic architecture represents one of the most common structural motifs in nonribosomal peptides, with nearly three-quarters of NRPs featuring cyclic components [3]. These structures provide enhanced metabolic stability and conformational restraint that often translates to improved biological activity.

Macrocyclization Mechanisms

The cyclization of nonribosomal peptides is primarily mediated by thioesterase (TE) domains that catalyze intramolecular cyclization rather than hydrolysis [26] [29]. These TE domains recognize the full-length peptide tethered to the final T domain and facilitate nucleophilic attack by an internal functional group (typically a hydroxyl, amine, or thiol side chain) on the thioester bond, resulting in macrocyclization and product release [26]. In some cases, such as the cyclic hexapeptide fusahexin, additional structural features like uncommon ether bonds between proline C-δ and threonine C-β further increase structural complexity [29].

Cyclic Peptide Structural Classes

Cyclic nonribosomal peptides exhibit significant variation in their cyclization patterns, including:

- Homodetic cyclic peptides: Feature backbone amide bonds between the N- and C-termini, such as cyclosporine [3].