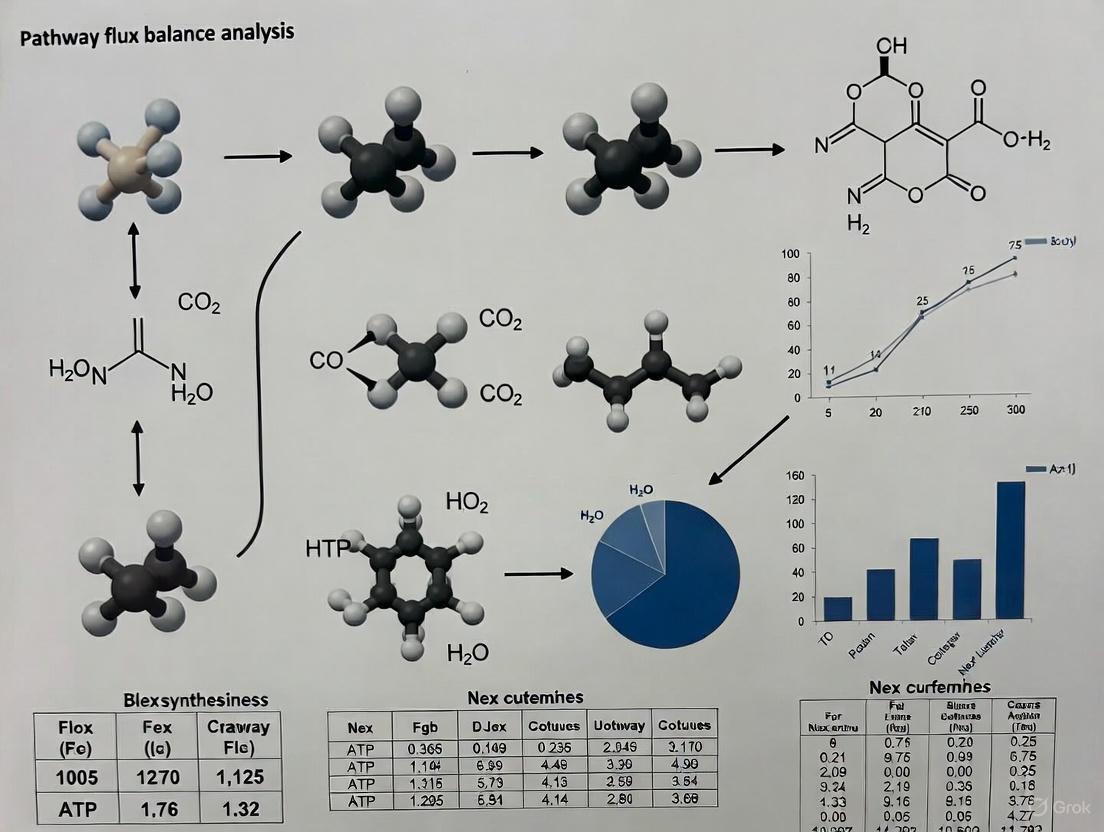

Resolving Pathway Flux Balance Challenges: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Validation in Metabolic Engineering

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the persistent challenges in metabolic pathway flux balance analysis (FBA).

Resolving Pathway Flux Balance Challenges: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Validation in Metabolic Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the persistent challenges in metabolic pathway flux balance analysis (FBA). It explores the foundational principles of constraint-based modeling, examines advanced methodological frameworks like TIObjFind that integrate FBA with metabolic pathway analysis, and presents practical strategies for troubleshooting optimization bottlenecks. The content critically reviews validation techniques and model selection criteria to enhance predictive accuracy, offering a holistic perspective on translating in silico flux predictions into reliable biological insights for biomedical and biotechnological applications.

Understanding Flux Balance Analysis: Core Principles and Persistent Challenges in Metabolic Modeling

Core Mathematical Principles

What is the fundamental mathematical problem that Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) solves?

FBA is a mathematical approach for analyzing the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network. It finds an optimal net flow of mass through the network that follows a set of constraints defined by the user [1]. The core problem is solving for the flux vector v that satisfies the steady-state mass balance equation [2]:

Sv = 0

where S is the stoichiometric matrix of size m × n (m metabolites and n reactions), and v is the vector of reaction fluxes. This system is typically underdetermined (more reactions than metabolites), so linear programming is used to find a unique solution that maximizes or minimizes a biological objective function [2] [3].

How does the steady-state assumption constrain the solution space?

The steady-state assumption requires that the concentration of internal metabolites remains constant. This means the rate of production must equal the rate of consumption for each metabolite [1] [3]. Mathematically, this is represented by the mass balance equations where the sum of fluxes producing a metabolite equals the sum of fluxes consuming it. This constraint eliminates dynamically changing flux distributions and focuses the analysis on balanced metabolic states that can be maintained over time [2].

Table: Key Components of the FBA Mathematical Framework

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | Matrix of coefficients (m metabolites × n reactions) | Network structure: defines metabolite participation in reactions [1] [2] |

| Flux Vector (v) | v = [v₁, v₂, ..., vₙ]ᵀ | Reaction rates through each metabolic pathway [1] |

| Mass Balance Constraints | Sv = 0 | Metabolic steady state: no net accumulation of internal metabolites [2] [3] |

| Flux Constraints | lb ≤ v ≤ ub | Thermodynamic and capacity constraints on reaction rates [4] |

| Objective Function | Z = cᵀv | Biological goal to optimize (e.g., biomass production) [1] [2] |

Troubleshooting Infeasible FBA Problems

Why does my FBA problem become infeasible when I integrate measured flux values?

Infeasibility occurs when known (e.g., measured) fluxes of certain reactions create inconsistencies that violate the steady-state or other constraints [4]. This typically happens when:

- Measurement inconsistencies: Some measured fluxes conflict with others, causing violation of mass balance constraints [4]

- Thermodynamic violations: Fixed flux values force reactions to proceed in thermodynamically infeasible directions [4]

- Bound conflicts: The combination of fixed values and flux bounds creates an empty solution space [4]

What methods can resolve infeasible FBA scenarios?

Two primary methods can find minimal corrections to given flux values to make FBA problems feasible [4]:

Linear Programming (LP) Approach: Finds the minimal set of flux corrections by minimizing the sum of absolute deviations between measured and adjusted fluxes [4]

Quadratic Programming (QP) Approach: Finds corrections by minimizing the sum of squared deviations, which tends to distribute small corrections across multiple fluxes rather than concentrating them on a few [4]

Table: Comparison of Infeasibility Resolution Methods

| Method | Mathematical Formulation | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LP-Based | min Σᵢ│vᵢ - fᵢ│ subject to Sv = 0, lb ≤ v ≤ ub | Simpler computation; tends to sparse solutions (few corrected fluxes) [4] | May produce extreme flux distributions [4] |

| QP-Based | min Σᵢ(vᵢ - fᵢ)² subject to Sv = 0, lb ≤ v ≤ ub | Smoother corrections; better for normally distributed measurement errors [4] | More computationally intensive; corrections spread across multiple fluxes [4] |

Computational Workflow & Experimental Protocols

FBA Computational Workflow

Protocol: Performing Basic Flux Balance Analysis

Objective: Calculate the optimal flux distribution for biomass production in a metabolic network [1] [2]

Materials:

- Computer with linear programming solver [1]

- Metabolic network reconstruction [2]

- Programming environment (e.g., Python3 with appropriate libraries, MATLAB with COBRA Toolbox) [1] [2]

Methodology:

- Network Representation: Encode the metabolic network as a stoichiometric matrix where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions [1] [2]

- Constraint Definition:

- Objective Function: Formulate objective as Z = cᵀv, where c is a vector with 1 at the position of the biomass reaction and 0 elsewhere [2]

- Linear Programming Solution: Use simplex method or other LP algorithms to find v that maximizes Z subject to all constraints [1]

- Validation: Compare predicted growth rates with experimental measurements when available [2]

Troubleshooting:

- If problem is infeasible, use LP or QP correction methods to identify inconsistent constraints [4]

- If solution is non-unique, perform flux variability analysis to identify ranges of possible fluxes [2]

Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

Table: Essential Components for FBA Implementation

| Component | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix | Encodes network structure; defines metabolite relationships in reactions [1] [2] | Sparse matrix representation in computational software [2] |

| Linear Programming Solver | Computes optimal flux distribution [1] | Python's SciPy, MATLAB's linprog, COBRA Toolbox [1] [2] |

| Flux Constraints | Incorporates thermodynamic and regulatory limitations [4] | Lower/upper bounds on reaction fluxes [4] |

| Objective Function | Defines biological goal for optimization [2] | Biomass reaction for growth simulation [2] |

| Null Space Analysis | Identifies feasible flux routes under steady state [1] | Singular value decomposition of stoichiometric matrix [1] |

FBA Mathematical Structure

Advanced Applications & Methodologies

How can FBA be used for metabolic engineering and drug target identification?

FBA enables systematic identification of modifications to metabolic networks that improve product yields of industrially important chemicals [3]. For drug target identification, FBA can:

- Identify essential reactions: Delete each reaction and measure impact on biomass production [3]

- Find synthetic lethal pairs: Identify non-essential reaction pairs whose simultaneous deletion is lethal [3]

- Predict gene essentiality: Convert reaction essentiality to gene essentiality using gene-protein-reaction relationships [3]

Protocol: Gene Deletion Analysis Using FBA

Objective: Identify essential genes for bacterial growth [3]

Methodology:

- Represent Gene-Reaction Relationships: Encode Boolean gene-protein-reaction (GPR) expressions [3]

- Simulate Gene Deletions: For each gene, constrain associated reaction fluxes to zero based on GPR rules [3]

- Compute Growth Phenotype: Perform FBA with biomass maximization for each deletion mutant [3]

- Classify Gene Essentiality: Genes causing significant growth defect when deleted are classified as essential [3]

Interpretation:

- Single gene essentiality: Reactions catalyzed by essential gene products are potential drug targets [3]

- Synthetic lethality: Non-essential gene pairs whose simultaneous deletion is lethal represent combinatorial drug targets [3]

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone constraint-based method for modeling genome-scale metabolic networks. By leveraging stoichiometric models and optimization principles, FBA predicts metabolic flux distributions that maximize or minimize specific biological objective functions under steady-state conditions [5]. While powerful, traditional FBA faces three interconnected challenges that can limit its predictive accuracy: the selection of appropriate objective functions, capturing dynamic metabolic adaptations, and managing inherent network complexity. This technical guide addresses these challenges through troubleshooting FAQs and experimental solutions framed within pathway flux balance research.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs & Solutions

Objective Function Selection

Q: How can I determine the most biologically relevant objective function for my specific organism and experimental conditions?

The Challenge: The predictive accuracy of FBA is highly sensitive to the chosen objective function. While biomass maximization is common for microbes, it doesn't universally apply across all organisms or environmental contexts [6] [5]. Suboptimal choices can lead to physiologically irrelevant flux predictions.

Solution Framework: Implement the Topology-Informed Objective Find (TIObjFind) framework to systematically identify context-specific objective functions [7] [8].

Experimental Protocol:

- Input Preparation: Gather your genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) and experimental flux data (

v_exp) for key metabolites under study conditions. - Optimization Problem Setup: Formulate an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between FBA-predicted fluxes and

v_exp, while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal. - Mass Flow Graph (MFG) Construction: Map the FBA solution to a directed, weighted graph

G(V,E)where nodes represent reactions and edge weights represent metabolic fluxes. - Pathway Analysis: Apply a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to the MFG to identify critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs). These coefficients quantify each reaction's contribution to the overall objective [7].

- Validation: Use the derived CoIs as weights in a new objective function (

c_obj · v) and validate against a separate set of experimental data.

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function in TIObjFind |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | Provides stoichiometric matrix (S) and flux constraints (vmin, vmax). |

| Experimental Flux Data (v_exp) | Serves as ground truth for aligning model predictions. |

| MATLAB with maxflow package | Computes minimum cut sets for pathway identification [7]. |

| COBRApy Toolbox | Performs standard FBA simulations and model manipulation [9]. |

| BRENDA/PAXdb Databases | Sources for enzyme kinetic data (Kcat) and protein abundance [9]. |

Visualization: TIObjFind Workflow

Dynamic Response Limitations

Q: My FBA model fails to predict metabolic shifts over time or in response to environmental perturbations. How can I capture these dynamic adaptations?

The Challenge: Standard FBA operates at steady-state, making it unsuitable for predicting transient metabolic states or responses to changing nutrient availability, which are crucial for understanding processes like replicative ageing or bioprocess fermentation [6].

Solution Framework: Employ multi-scale modeling that integrates FBA with dynamic modules or use Dynamic FBA (dFBA).

Experimental Protocol:

- Multi-Scale Integration: Couple your FBA model with an Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) system that tracks damage accumulation, biomass growth, and extracellular metabolite concentrations over time [6].

- Lexicographic Optimization: Perform sequential optimizations to handle multiple objectives. First, optimize for a primary objective (e.g., biomass). Then, constrain the solution to this optimum (allowing a small flexibility factor, ε) and optimize for a secondary objective (e.g., ATP production or minimal nutrient uptake) [6].

- Dynamic FBA (dFBA): Implement dFBA by repeatedly solving an FBA problem at discrete time intervals. Update the model's constraints (e.g., substrate uptake rates) at each step based on the simulated consumption and production from previous steps.

- Regulatory Constraints: Incorporate Boolean logic rules (as in rFBA) to constrain reaction fluxes based on gene expression states or environmental signals [7] [8].

Quantitative Data from Ageing Study: The table below shows how different objective functions in a multi-scale model of yeast ageing lead to varying predictions for lifespan and generation time [6].

| Objective Function | Predicted Lifespan (Cell Divisions) | Average Generation Time | Key Metabolic Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximal Growth (Parsimonious) | 23 | ~1.5 hours | Reference (wild-type) cell |

| Maximal ATP Production | Improved predictions | Varied | Increased respiratory activity |

| Multi-Objective Optimization | Improved predictions | Varied | Enhanced antioxidative activity in early life |

Network Complexity

Q: The complexity of my genome-scale model makes the FBA results difficult to interpret or validate. How can I simplify the analysis without losing biological insight?

The Challenge: Dense, interconnected metabolic networks produce high-dimensional solution spaces. Interpreting optimal flux distributions and relating them to specific pathway activities is non-trivial [5] [7].

Solution Framework: Deconstruct the network using Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) and graph-based algorithms to focus on functionally relevant sub-networks.

Experimental Protocol:

- Pathway-Centric Analysis: Instead of analyzing all reactions, use MPA tools like Elementary Flux Modes or Extreme Pathways to decompose the network into meaningful functional units [5].

- Targeted Sub-Network Analysis: Define a "start" reaction (e.g., glucose uptake) and a "target" reaction (e.g., product secretion). Use the TIObjFind framework to compute the Mass Flow Graph and apply a minimum-cut algorithm to identify the most critical pathways connecting these points [7] [8].

- Enzyme Constraints: Add realism and reduce solution space by incorporating enzyme capacity constraints using the ECMpy workflow [9]. This involves adding a total enzyme pool constraint based on enzyme kinetic data (kcat) and molecular weights.

- Gap Filling: Manually curate the model by adding missing reactions critical for your study (e.g., thiosulfate assimilation pathways for L-cysteine production) based on organism-specific databases like EcoCyc [9].

Visualization: Constraint-Based Modeling Workflow

| Item | Category | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| COBRApy | Software Toolbox | Python-based toolkit for performing FBA and related constraint-based analyses [9]. |

| ECMpy | Software Toolbox | Workflow for adding enzyme constraints to a GEM without altering its core structure [9]. |

| TIObjFind Framework | Software/Method | Integrated framework (MPA + FBA) for identifying context-specific objective functions [7] [8]. |

| BRENDA Database | Database | Curated source of enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat values) [9]. |

| EcoCyc / KEGG | Database | Resources for organism-specific metabolic pathways and gap-filling [7] [9]. |

| Lexicographic Optimization | Mathematical Method | Handles multiple cellular objectives by sequential optimization [6]. |

| Mass Flow Graph (MFG) | Analytical Construct | A directed graph representation of flux distributions for pathway analysis [7] [8]. |

| Minimum-Cut Algorithm | Algorithm | Identifies critical, high-flux pathways within a complex MFG [7]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing and Resolving Epistatic Interaction Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Epistasis-Related Roadblocks in Pathway Engineering

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Approach | Resolution Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low product yield despite high pathway gene expression | Incoherent epistasis: Synergistic for one phenotype but antagonistic for target metabolite production [10]. | - Construct multi-phenotype epistasis maps [10]- Measure flux distributions for single/double mutants | - Refactor pathway genes to minimize antagonistic interactions- Use dynamic regulation to decouple growth and production [11] |

| Unpredicted gene essentiality in engineered strain | Background-dependent epistasis: Network context alters essentiality predictions [12] [13]. | - Compare FBA predictions with topology-based ML models [13]- Perform gene deletion screens in relevant genetic backgrounds | - Identify alternative pathways using tools like SubNetX [14]- Incorporate network topology analysis into essentiality assessment [13] |

| Unstable production across scale-up or prolonged fermentation | Metabolic burden and subpopulation emergence due to lack of autonomous regulation [11]. | - Monitor metabolite dynamics and population heterogeneity [15]- Analyze flux balance under different conditions | - Implement dynamic control circuits with metabolite biosensors [11]- Adopt two-stage fermentation strategies [11] |

| Inaccurate FBA predictions of pathway performance | Biological redundancy allowing flux rerouting in simulations that doesn't occur in vivo [13]. | - Benchmark FBA against curated experimental data [13]- Compare with topology-based predictions | - Supplement FBA with machine learning approaches using graph-theoretic features [13]- Incorporate kinetic constraints into models [15] |

| Inability to connect pathway to host metabolism stoichiometrically | Unbalanced subnetwork designs lacking cofactor and cosubstrate connectivity [14]. | - Use constraint-based optimization to check stoichiometric feasibility [14]- Analyze cofactor balance in proposed pathways | - Apply SubNetX algorithm to extract balanced subnetworks [14]- Ensure cofactors link to native host metabolism |

Addressing Metabolic Control and Flux Imbalance Issues

Table 2: Metabolic Flux Control and Modeling Troubleshooting

| Problem Category | Specific Symptoms | Diagnostic Methods | Verified Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Control Failures | - Oscillating metabolite levels- Inconsistent TRY metrics across bioreactors [11] | - Build kinetic models of pathway enzymes and metabolites [15]- Simulate control system response to perturbations | - Implement bistable switches with hysteresis for robust two-stage control [11]- Use surrogate ML models to speed up FBA-in-loop simulations [15] |

| Pathway Connectivity Gaps | - Accumulation of pathway intermediates- Failure to produce complex molecules from simple precursors [14] | - Search biochemical databases (ARBRE, ATLASx) for missing reactions [14]- Check for unbalanced reactions in proposed pathways | - Expand known reaction networks with computationally predicted reactions [14]- Design balanced pathways using mixed-integer linear programming [14] |

| Resource Competition | - Reduced host growth and fitness- Declining production over time [11] | - Quantify metabolic burden via omics analysis- Measure cellular resource allocation (ATP, cofactors) | - Decouple growth and production phases using two-stage systems [11]- Engineer resource-aware pathways with appropriate promoter strengths |

| Kinetic-Phenotype Mismatch | - Accurate flux predictions but incorrect metabolite dynamics [15] | - Integrate kinetic models with genome-scale metabolic models [15]- Validate against time-course metabolite data | - Combine FBA with local kinetic models for better dynamic prediction [15]- Use machine learning surrogates for FBA to enable kinetic integration [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing Multi-Phenotype Epistasis Maps

Purpose: To systematically identify epistatic interactions across multiple metabolic flux phenotypes, revealing 8-fold more interactions than single growth phenotype analysis [10].

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., S. cerevisiae model [10])

- Computational resources for flux balance analysis

- Software for minimization of metabolic adjustment (MOMA)

Methodology:

- Generate Single Mutants: Compute all possible single enzyme gene deletions in the metabolic model using constraint-based modeling.

- Generate Double Mutants: Compute all possible double enzyme gene deletions using the same approach.

- Calculate Flux Phenotypes: For each mutant, calculate steady-state metabolic reaction rates (fluxes) for all metabolic reactions in the model. The experimentally driven variant of MOMA provides best correlation with measured fluxes (Spearman rank correlation >0.90) [10].

- Quantify Epistasis: For each gene pair and each flux phenotype, calculate epistasis coefficients using a multiplicative model:

- ε = (Fij - Fi * Fj) where Fij is the double mutant flux, Fi and Fj are single mutant fluxes

- Classify interactions as synergistic (ε > 0) or antagonistic (ε < 0) [10]

- Construct 3D Matrix: Build a matrix with dimensions: Gene A × Gene B × Flux Phenotype containing epistasis coefficients.

- Validate Interactions: Compare predictions with experimental flux measurements where available [10].

Interpretation: Genes involved in many interactions across phenotypes are typically highly expressed, evolve slower, and may associate with diseases, indicating their biological importance [10].

Protocol 2: Implementing Dynamic Metabolic Control Systems

Purpose: To engineer autonomous metabolic control that improves titer, rate, and yield (TRY) metrics by dynamically adjusting flux in response to metabolic state [11].

Materials:

- Microbial chassis (E. coli, yeast)

- Metabolic biosensors (transcription factor-based)

- Inducible expression systems

- Genome-scale metabolic model of host

Methodology:

- Valve Identification: Use computational algorithm to identify metabolic reactions that can serve as "valves" to switch between biomass production (growth phase) and metabolite production (production phase) [11].

- Sensor Selection: Choose or engineer biosensors that respond to key pathway metabolites, internal metabolic state, or external environment [11].

- Circuit Design: Design genetic circuits that link sensor input to valve control:

- For two-stage systems: engineer bistable switches with hysteresis for robust switching [11]

- For continuous control: implement proportional response systems

- Integration and Testing: Integrate control system into host genome and test in laboratory bioreactors.

- Model-Based Optimization: Use kinetic modeling to optimize control parameters:

- Scale-Up Validation: Validate performance in industrial-scale fermentation conditions [11].

Interpretation: Dynamic control systems can overcome metabolic burden, improve resource allocation, and maintain production stability in varying conditions [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does FBA often fail to predict gene essentiality accurately in engineered pathways?

A: FBA fails primarily due to biological redundancy in metabolic networks. The optimization-based approach can reroute flux through alternative pathways isozymes in simulations, predicting minimal growth impact when the gene is actually essential in vivo. This results in high specificity but low sensitivity. A topology-based machine learning approach that uses graph-theoretic features (betweenness centrality, PageRank) has been shown to decisively outperform FBA, achieving an F1-score of 0.400 compared to 0.000 for FBA on the E. coli core network [13].

Q2: How can we identify epistatic interactions that specifically impact our target product yield?

A: Traditional epistasis maps based on growth phenotype capture only a fraction (approximately 1/8th) of relevant interactions. Construct multi-phenotype epistasis maps relative to all metabolic flux phenotypes, which plateau at approximately 80 phenotypes and reveal 8-fold more interactions. This approach can identify "incoherent" epistasis where gene pairs interact synergistically for some phenotypes but antagonistically for others, including your target product [10].

Q3: What computational tools can help design pathways for complex biochemical production?

A: Use SubNetX, an algorithm that combines constraint-based and retrobiosynthesis methods to extract and assemble balanced subnetworks from biochemical databases. It connects target molecules to host metabolism through multiple precursors while maintaining stoichiometric balance of cofactors and energy currencies. The tool can process large reaction networks (>400,000 reactions) and identify feasible pathways for complex natural and non-natural compounds [14].

Q4: When should we implement a two-stage versus continuous dynamic control system?

A: Choose two-stage control for batch processes where nutrients become limited, as it decouples growth and production phases. Choose continuous control for fed-batch processes with constant nutrient availability. Theoretical models show that in constant nutrient environments, one-stage fermentation with high metabolic activity is preferred, while in nutrient-limited conditions, two-stage processes with dedicated production phases outperform one-stage approaches [11].

Q5: How does epistasis propagate from enzymatic level to organismal fitness?

A: Theory shows that epistasis between mutations with small effects propagates from lower- to higher-level phenotypes in hierarchical metabolic networks with first-order kinetics. Weak epistasis at the enzymatic level may become distorted as it propagates to higher levels, meaning pairwise inter-gene epistasis commonly depends on genetic background and environment. Therefore, epistasis coefficients measured for high-level phenotypes may not directly reveal underlying functional relationships [12].

Q6: What strategies can overcome metabolic burden in engineered strains?

A: Implement dynamic metabolic control systems that autonomously adjust flux in response to metabolic state. This includes two-stage switches that separate growth and production phases, continuous control using metabolite biosensors, and population control mechanisms. These approaches reduce resource competition, prevent toxic metabolite accumulation, and improve stability against non-producing mutants [11].

Pathway Diagrams and Workflows

Multi-Phenotype Epistasis Mapping Workflow

Dynamic Metabolic Control System Architecture

Epistasis Propagation in Metabolic Networks

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Pathway Engineering

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Applications | Implementation Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SubNetX [14] | Extracts and assembles balanced subnetworks from biochemical databases | - Designing pathways for complex natural products- Connecting heterologous pathways to host metabolism | - Requires biochemical reaction database input- Can process networks of >400,000 reactions- Outputs feasible pathways ranked by yield and thermodynamics | |

| Pathway Tools [16] | Comprehensive software for genome informatics and systems biology | - Metabolic reconstruction- Flux-balance modeling- Omics data visualization and analysis | - Powers BioCyc database collection- Includes MetaFlux for flux modeling- Free for academic/research use | |

| BioKIT [17] | Versatile toolkit for processing and analyzing biological sequences | - Genome assembly quality assessment- Relative synonymous codon usage analysis- File format conversion | - 42 functions for diverse bioinformatic analyses- Supports alternative genetic codes- Useful for codon optimization in heterologous expression | |

| Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) [10] | Predicts metabolic fluxes in mutant strains | - Computing epistatic interactions- Predicting double mutant phenotypes | - Experimentally driven variant shows >0.90 Spearman correlation with measured fluxes- Based on hypothesis of minimal flux rerouting after perturbation | |

| Topology-Based ML Models [13] | Predicts gene essentiality using graph-theoretic features | - Identifying essential genes for drug targeting- Complementing FBA predictions | - Uses betweenness centrality, PageRank, closeness centrality- Random Forest implementation handles imbalanced data | - Decisively outperforms FBA on E. coli core network (F1: 0.400 vs 0.000) |

| Dynamic Control Theory Framework [11] | Provides design principles for metabolic control systems | - Implementing two-stage fermentations- Engineering continuous metabolic control | - Incorporates bistability for robust switching | - Considers hysteresis for noise filtering- Guides sensor-actuator selection and circuit design |

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Common FBA Inaccuracies

Problem 1: Model Infeasibility or Inability to Produce Biomass

- Error Message/Symptom: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) solver returns a non-zero solution or fails to produce biomass precursors.

- Root Cause: Draft metabolic models, derived from genome annotations, often lack essential reactions due to missing or incorrect annotations. Common issues include incomplete metabolic pathways and missing transporters that move metabolites across cell membranes [18].

- Resolution:

- Perform Gap-Filling: Use a computational gap-filling algorithm to suggest a minimal set of reactions to add to your model, enabling biomass production on a specified growth medium [19] [18].

- Strategy: Start the gap-filling process on a minimal media. This forces the algorithm to add the maximal set of biosynthetic reactions, ensuring the model can produce necessary substrates, rather than relying on them being present in a rich media [18].

- Verification: After gap-filling, verify that the model can now produce all biomass components on your intended growth medium.

Problem 2: Prediction of Theoretically Possible but Biologically Irrelevant Fluxes

- Error Message/Symptom: FBA predicts growth or metabolite production that does not align with experimental data, or fluxes are concentrated in unrealistic, high-yield pathways.

- Root Cause: The standard FBA formulation may lack biological constraints present in real cells, such as limited enzyme capacity or regulatory mechanisms [20] [21].

- Resolution:

- Apply a Total Enzyme Activity Constraint: Limit the sum of enzyme concentrations in the model based on the assumption that the cell has limited resources for protein synthesis [20].

- Implement Thermodynamic Constraints: Apply constraints based on reaction directionality and energy balance to prevent thermodynamically infeasible cycles [20].

- Use a Hybrid Approach: Integrate experimental exometabolomic data with machine learning, as in the NEXT-FBA method, to derive biologically relevant bounds for intracellular fluxes [22].

Problem 3: Incorrect Objective Function Leading to Poor Flux Predictions

- Error Message/Symptom: FBA predictions consistently deviate from experimental fluxomic data (e.g., from 13C-labeling) under the same environmental conditions.

- Root Cause: The assumed cellular objective (e.g., biomass maximization) may not accurately reflect the organism's true metabolic priorities under all conditions [8].

- Resolution:

- Utilize the TIObjFind Framework: This framework integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to identify context-specific objective functions [8].

- Calculate Coefficients of Importance (CoIs): Use TIObjFind to quantify each reaction's contribution to an objective function that best aligns your model's predictions with the experimental flux data [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is gap-filling and how does the algorithm work?

Gap-filling is the process of completing a draft metabolic model by adding essential reactions from a reference database to allow the model to produce biomass on a specified growth medium [18]. The algorithm uses a cost function for reactions and aims to find a solution that requires the fewest additions to fill all gaps, often using Linear Programming (LP) to minimize the sum of flux through gapfilled reactions [18].

How do I choose a media condition for gap-filling?

It is often best to start with a minimal media for the initial gap-filling. This ensures the algorithm adds the necessary reactions for the model to biosynthesize many common substrates, rather than simply importing them from a rich medium [18]. Using "complete" media (an abstraction containing all transportable compounds in the biochemistry database) first may result in a model that is overly reliant on transport reactions and less predictive under different conditions [18].

Which reactions were added during gap-filling and why?

After gap-filling, you can typically sort the reactions in your model by a "Gapfilling" column. Reactions that are new and were added by the algorithm will be irreversible (e.g., => or <=). Reactions that were already present but made reversible by the process will be marked as <=> [18]. The primary reason for adding any reaction is to enable biomass production, but the process is a heuristic and may require manual curation to ensure biological relevance [18].

Methodologies & Data Presentation

The table below summarizes modern approaches that improve FBA predictions by incorporating experimental data.

| Framework/Method | Core Approach | Type of Experimental Data Used | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEXT-FBA [22] | Uses artificial neural networks (ANNs) to correlate exometabolomic data with intracellular fluxes. | Exometabolomic data from cell cultures. | Derives biologically relevant constraints for intracellular fluxes with minimal input data for pre-trained models. |

| TIObjFind [8] | Integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to infer metabolic objectives. | Experimental flux data (e.g., from 13C-labeling). | Identifies context-specific objective functions and quantifies reaction importance (Coefficients of Importance). |

| gapseq [23] | Uses a curated reaction database and LP-based gap-filling informed by sequence homology and network topology. | Genomic sequence; validated against large-scale phenotype data (e.g., enzyme activity, carbon source use). | Reduces false negative predictions and improves accuracy for non-model organisms. |

Gap-Filling Algorithm Performance Comparison

The following table compares the performance of different reconstruction tools based on a large-scale validation using experimental enzyme activity data [23].

| Software Tool | True Positive Rate | False Negative Rate | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| gapseq | 53% | 6% | Informed gap-filling using a curated database and sequence homology. |

| ModelSEED | 30% | 28% | Automated pipeline for high-throughput model generation. |

| CarveMe | 27% | 32% | Uses a universal model and directionality constraints. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Validation |

|---|---|

| 13C-labeled Substrates | Used in 13C fluxomics to trace the fate of carbon atoms through metabolic networks, providing experimental data for intracellular flux validation [8]. |

| Exometabolomic Profiling Kits | Enable quantitative measurement of extracellular metabolite concentrations, which serve as input for data-driven methods like NEXT-FBA [22]. |

| Enzyme Activity Assays | Provide ground-truth data for specific enzymatic functions (e.g., catalase, cytochrome oxidase) used to validate the presence of reactions in metabolic models [23]. |

| Curated Biochemistry Databases (e.g., MetaCyc, ModelSEED) | Serve as reference repositories of biochemical reactions for gap-filling algorithms and model reconstruction [19] [18]. |

Experimental Protocol: Workflow for Model Refinement Using Experimental Flux Data

The diagram below outlines a general workflow for integrating experimental data to improve model accuracy.

Technical Deep Dive: The TIObjFind Framework Workflow

For cases where standard gap-filling is insufficient, the TIObjFind framework provides a systematic method to infer cellular objectives from data.

Advanced FBA Frameworks and Practical Implementation for Pathway Optimization

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This technical support resource addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing the TIObjFind framework, a novel method that integrates Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) to identify context-specific metabolic objectives [7] [8].

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the primary function of TIObjFind and how does it improve upon traditional FBA? Traditional FBA often uses a static objective function, like biomass maximization, which can fail to capture flux variations under different environmental conditions [7]. TIObjFind addresses this by introducing a data-driven optimization framework that identifies Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) for reactions. These coefficients quantify each reaction's contribution to a cellular objective that best aligns with experimental flux data, thereby enhancing the biological relevance and accuracy of predictions [7] [8].

2. My TIObjFind predictions do not align with my experimental data. What could be wrong? Misalignment often stems from two sources:

- Insufficient or inaccurate experimental constraints: The framework requires high-quality experimental flux data (

vjexp) for key extracellular compounds to guide the optimization. Ensure your input data, such as uptake and secretion rates, is accurate and correctly applied as constraints in the initial FBA [7]. - Incorrect specification of start and target reactions: The Mass Flow Graph and subsequent pathway analysis are built between defined start (e.g., glucose uptake) and target (e.g., product secretion) reactions. Verify that these are correctly specified for your biological system [7].

3. Which minimum-cut algorithm is recommended for large, genome-scale models and why? The Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm is recommended due to its superior computational efficiency. It delivers near-linear performance across various graph sizes, making it significantly faster than conventional algorithms like Ford-Fulkerson or Edmonds-Karp for large-scale metabolic networks [7] [8].

4. How does TIObjFind prevent overfitting to specific experimental conditions? Unlike its predecessor (ObjFind), which could assign weights across all metabolites, TIObjFind focuses on specific pathways identified via Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA). This topology-informed method selectively evaluates fluxes in key pathways, which enhances interpretability and reduces the potential for overfitting to particular conditions [7] [8].

Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Data Integration | Large discrepancy between model predictions and experimental fluxes for key products. | Re-formulate the objective function selection as an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal [7]. |

| Model Interpretation | Difficulty identifying the most critical pathways in a dense metabolic network. | Map FBA solutions onto a Mass Flow Graph (MFG) and apply a minimum-cut algorithm to extract critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance [7]. |

| Computational Performance | Slow pathway analysis when working with multi-species models. | Implement the Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm for the minimum-cut calculation, as provided in MATLAB's maxflow package, to improve processing speed [7] [8]. |

| Biological Relevance | The model fails to capture adaptive metabolic shifts between different culture stages. | Use TIObjFind to analyze differences in Coefficients of Importance across different stages (e.g., acidogenesis vs. solventogenesis) to reveal shifting metabolic priorities [8]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Below is a step-by-step methodology for applying the TIObjFind framework, as illustrated in the published case studies [7] [8].

Protocol: Identifying Stage-Specific Metabolic Objectives

1. Prerequisite: Formulate the Base Metabolic Model

- Function: Represents the stoichiometry of all known biochemical reactions in the organism.

- Procedure: Reconstruct a genome-scale model or obtain a pre-existing model (e.g., iCAC802 for C. acetobutylicum). Define the system boundary by specifying exchange reactions for environmental nutrients and secreted products.

2. Step 1: Perform Initial FBA with Experimental Constraints

- Function: To generate candidate flux distributions that are both stoichiometrically feasible and consistent with experimental measurements.

- Procedure:

- Constrain the model with measured experimental data (e.g., glucose uptake rate, product secretion rates).

- Solve a single-stage optimization (Karush-Kuhn-Tucker formulation) of FBA to find flux distributions (

v*) that minimize the squared error from the experimental data (vexp) for a given candidate objective [7].

3. Step 2: Construct the Mass Flow Graph (MFG)

- Function: To translate the FBA solution into a directed, weighted graph for pathway analysis.

- Procedure:

- Represent the metabolic network as a graph

G(V,E), where reactions (V) are connected by edges (E) representing metabolite flow. - Use the derived flux distribution

v*to assign weights to the edges, creating a flux-dependent weighted reaction graph [7].

- Represent the metabolic network as a graph

4. Step 3: Apply Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with Minimum-Cut Algorithm

- Function: To identify essential pathways and calculate Coefficients of Importance (CoIs).

- Procedure:

- Select start (source,

s) and target (sink,t) reactions relevant to the study (e.g., glucose uptake and product secretion). - Apply a minimum-cut (max-flow) algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to the MFG to find the critical bottleneck between

sandt. - The results of this analysis are used to compute the Coefficients of Importance, which serve as pathway-specific weights [7].

- Select start (source,

5. Step 4: Infer the Objective Function and Validate

- Function: To identify the metabolic objective that best explains the experimental data.

- Procedure:

- Use the calculated CoIs as hypothesis coefficients within a new objective function (a weighted sum of fluxes).

- Validate the framework by comparing the flux predictions using this new objective function against a separate set of experimental data, ensuring a good match and capturing stage-specific metabolic objectives [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following tools and resources are critical for implementing the TIObjFind framework.

Table: Key Computational Tools for TIObjFind Implementation

| Item Name | Function/Application in TIObjFind | Specific Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MATLAB | Primary programming environment for implementing the TIObjFind optimization framework. | Hosts the custom code for the main analysis, including the KKT formulation and integration with the maxflow package [7] [8]. |

| MATLAB maxflow package | Performs the critical minimum cut set calculations on the Mass Flow Graph. | Used to identify essential pathways by computing the max-flow/min-cut between source and sink reactions [7]. |

| Boykov-Kolmogorov Algorithm | The specific algorithm used to solve the minimum-cut problem. | Selected for its computational efficiency and near-linear performance with large graphs [7]. |

| Python with pySankey | Used for the visualization of results and flux distributions. | Creates intuitive Sankey diagrams to visualize flux through different pathways, aiding in the interpretation of complex networks [7] [8]. |

| GitHub Repository | Source for all case study data, metabolic models, and supplemental codes. | Provides the scripts and data needed to replicate the Clostridium and IBE system case studies [8]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core TIObjFind workflow.

TIObjFind Framework Core Workflow

The diagram below shows the flow of information from a simple metabolic model through to the final calculation of the Coefficients of Importance.

From Metabolic Model to Coefficients of Importance

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: What are Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) and what is their primary function? Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) are quantitative metrics that measure each metabolic reaction's contribution to a cellular objective function within a metabolic network model [8] [24]. Their primary function is to align Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) predictions with experimental flux data, thereby enhancing the interpretability of complex metabolic networks and providing insights into adaptive cellular responses under different environmental conditions [8].

FAQ: My FBA predictions do not align with experimental flux data. How can CoIs help? Misalignment often stems from using an inappropriate or static objective function. The TIObjFind framework addresses this by determining pathway-specific CoIs. It solves an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while inferring a weighted metabolic objective based on the network's topology [8]. This method prioritizes critical reactions and pathways, which can rectify discrepancies between your model and experimental observations.

FAQ: How do I determine which reactions to assign CoIs to in a large metabolic network? Applying CoIs to an entire genome-scale model can lead to overfitting. The TIObjFind framework recommends focusing on specific pathways of interest. You should identify start reactions (e.g., glucose uptake as a primary metabolic input) and target reactions (e.g., product secretion). A path-finding algorithm is then used to analyze the Coefficients of Importance between these selected points, highlighting critical connections within the dense network [8].

FAQ: Can CoIs capture metabolic shifts over time or under different conditions? Yes, a key application of CoIs is analyzing differences in metabolic priorities across various stages of a biological system [8]. By applying the TIObjFind framework to data from different conditions (e.g., different growth phases or nutrient availability), you can compute stage-specific CoIs. Examining the differences in these coefficients reveals how the network dynamically reallocates fluxes to adapt to environmental changes.

FAQ: What software tools are available for implementing the TIObjFind framework and calculating CoIs?

The TIObjFind framework was implemented in MATLAB, utilizing its maxflow package for the minimum-cut calculations central to the algorithm [8]. For visualization of results, such as Sankey diagrams of metabolic fluxes, the Python package pySankey can be used. Scripts and case study data are available from the cited research group's GitHub repository [8].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Materials and Computational Tools for CoI Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example/Model |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB/Python toolbox for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis of metabolic networks. | Used for performing standard FBA [25]. |

| OptFlux | An open-source software platform for in silico metabolic engineering using constraint-based models. | Used for performing standard FBA [25]. |

| FASIM | A tool for Flux Balance Analysis simulation and analysis. | Used for performing standard FBA [25]. |

| TIObjFind Framework | A custom framework integrating MPA with FBA to compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs). | Implemented in MATLAB; available on GitHub [8]. |

| Metabolic Network Reconstructions | Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) providing the stoichiometric matrix (S) for FBA. | Models for E. coli, C. acetobutylicum (iCAC802), and C. ljungdahlii (iJL680) [8]. |

| Experimental Flux Data | Quantitative measurements of metabolic reaction rates, essential for validating and informing model predictions. | Data from techniques like isotopomer analysis [8]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Table: Protocol for Identifying Metabolic Objectives with TIObjFind

| Step | Action | Purpose & Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Problem Formulation | Define an optimization problem that minimizes the difference (e.g., sum of squared deviations) between predicted FBA fluxes and experimental flux data, while maximizing an inferred, weighted metabolic goal. | This scalarizes a multi-objective problem, balancing model accuracy with biological relevance [8]. |

| 2. Construct Mass Flow Graph (MFG) | Map the FBA solution onto a directed graph where nodes represent metabolic reactions and edge weights represent flux values. | This provides a pathway-based interpretation of the metabolic flux distribution, integrating network topology [8]. |

| 3. Apply Minimum-Cut Algorithm | Use a graph theory algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) on the MFG to find the critical pathway between a defined start reaction (e.g., glucose uptake) and a target reaction (e.g., product secretion). | This step efficiently identifies the most critical fluxes and connections, improving interpretability. The algorithm is chosen for its computational efficiency [8]. |

| 4. Compute Coefficients of Importance | Calculate the CoIs based on the results of the minimum-cut, which quantify each reaction's additive contribution to the objective function. | A higher coefficient indicates that a reaction's flux is closely aligned with its maximum potential under the given conditions [8]. |

| 5. Validate & Interpret | Compare the model predictions using the new CoI-weighted objective function against a separate set of experimental data. Analyze shifts in CoIs across different biological stages. | Validation confirms the model's predictive power. Interpreting CoI shifts reveals changing metabolic priorities, such as in a multi-species IBE fermentation system [8]. |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows and Pathways

TIObjFind Computational Workflow

Metabolic Objective Finding Logic

Core FBA Concepts & Workflow

What is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)?

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a constraint-based computational method used to predict the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network. It analyzes the metabolic capabilities of an organism by applying constraints based on stoichiometry, thermodynamics, and enzyme capacity [26]. FBA calculates the optimal flux distribution that maximizes a specific biological objective, such as biomass production or ATP synthesis, under steady-state assumptions [26] [27].

Standard FBA Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the typical workflow for performing Flux Balance Analysis.

Model Selection & Setup

How do I select an appropriate metabolic model for my FBA study?

Model selection depends on your biological system and research question. Consider these factors:

- Organism Specificity: Choose a genome-scale model (GSM) that matches your organism of study. For human metabolic studies, Recon3D is the most comprehensive reconstruction [26].

- Tissue Context: For multicellular organisms, select tissue-specific models. Methods like iMAT or INIT can create context-specific models from expression data [26].

- Model Quality: Prefer models that have been experimentally validated and cited extensively. Check databases like BioModels or the systems biology repository at UCSD [26].

What are the essential steps for preparing a model for FBA?

Constraint Definition & Configuration

What types of constraints are essential for FBA?

FBA relies on multiple constraint types to obtain biologically relevant solutions:

Table 1: Essential Constraint Types in FBA

| Constraint Type | Mathematical Representation | Biological Basis | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-State | S · v = 0 | Metabolic concentrations remain constant over time [26] | Applied automatically by COBRApy |

| Reaction Bounds | α ≤ v ≤ β | Thermodynamic constraints and enzyme capacity [26] | model.reactions.EX_glc__.bounds = (-10, 0) |

| Nutrient Availability | vuptake ≤ maxuptake | Environmental nutrient limitations | Set exchange reaction bounds |

| Gene Knockouts | v = 0 if gene deleted | Genetic modifications | cobra.manipulation.delete_model_genes(model, ['gene1']) |

How do I define constraints for different environmental conditions?

Environmental constraints are implemented through exchange reactions:

Software Tools & Solver Configuration

How do I set up COBRApy with different solvers?

COBRApy uses optlang as an interface to mathematical solvers [28]. The configuration process is straightforward:

What are the key differences between solver options?

Table 2: Comparison of FBA Solvers

| Solver | Type | License | Performance | Installation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLPK | Open-source | Free | Good for small-medium models | Automatic with COBRApy [29] |

| Gurobi | Commercial | Paid, free academic | Excellent for large models | pip install gurobi |

| CPLEX | Commercial | Paid, free academic | Excellent for large models | pip install cplex |

Common FBA Challenges & Troubleshooting

Why does my model show no flux through the network?

Problem: Model returns zero flux for all reactions or cannot find a feasible solution.

Solutions:

- Check exchange reactions: Ensure nutrient uptake reactions are properly set

- Verify reaction bounds: Confirm no essential reactions are constrained to zero

- Test model integrity: Use

model.validate()to check for stoichiometric inconsistencies

How can I improve agreement between FBA predictions and experimental data?

Recent frameworks like TIObjFind address this by integrating Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA [7]. This approach:

- Determines Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution

- Uses topology information to identify critical pathways

- Minimizes differences between predicted and experimental fluxes [7]

Implementation requires additional optimization steps beyond basic FBA:

How do I handle objective function selection for complex systems?

For multicellular systems or changing environmental conditions, consider:

- Multi-objective optimization: Combine biomass with other cellular functions

- Dynamic FBA (dFBA): Simulate time courses using outputs from earlier steps as inputs for next steps [26]

- Regulatory FBA (rFBA): Integrate Boolean logic-based rules with FBA to account for gene regulation [26] [7]

Essential Research Reagents & Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for FBA Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled substrates | Enable experimental flux measurement via 13C-MFA [27] | Validation of FBA-predicted fluxes |

| GC-MS or LC-MS | Analytical platforms for metabolite detection and quantification | Measurement of extracellular fluxes and intracellular metabolites |

| Cell culture media | Defined nutrient conditions for constraint definition | Setting realistic boundary conditions for FBA |

| Gene knockout strains | Validation of model predictions through genetic manipulation | Testing essentiality predictions from FBA |

| Antibiotics/Inhibitors | Chemical perturbation of metabolic pathways | Testing model predictions under pathway inhibition |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why does my genome-scale metabolic model (GSMM) fail to predict the production of a known secondary metabolite?

- Problem: A common issue in pathway flux balance research is that reconstructed GSMMs often lack complete pathways for secondary metabolites, leading to false-negative predictions.

- Solution:

- Cause: Standard automated reconstruction tools (e.g., CarveMe, ModelSEED) and major metabolic databases (e.g., BiGG, SEED) have limited coverage of species-specific secondary metabolic pathways [30].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Utilize Specialized Tools: Employ BGC-based pathway reconstruction tools like BiGMeC (for polyketides and nonribosomal peptides) or retrosynthesis tools like BioNavi-NP to augment your model [30].

- Manual Curation: Manually curate the pathway into the GSMM using literature and experimental evidence. Be aware that this is labor-intensive and may omit intermediary metabolites, potentially hiding bottlenecks [30].

- Preventive Measure: Always verify the completeness of the biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) for your target metabolite using genome mining tools like antiSMASH before model reconstruction [30].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the accuracy of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) predictions for secondary metabolite production, which often does not align with growth objectives?

- Problem: Conventional FBA, which optimizes for biomass production, often fails to accurately predict fluxes towards secondary metabolites, as their synthesis is not always coupled with growth [30].

- Solution:

- Cause: The standard biomass objective function does not represent the regulatory and ecological triggers for secondary metabolism [30].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Alternative Objective Functions: Define a custom objective function that directly maximizes the flux through the reaction producing the target secondary metabolite [1].

- Apply Additional Constraints: Incorporate transcriptomic or proteomic data to constrain the flux bounds of specific reactions, forcing the model to redirect flux according to experimental conditions [31].

- Dynamic FBA: Implement dynamic FBA to simulate time-varying changes in the extracellular environment, which can trigger secondary metabolite production [30].

FAQ 3: What are the best strategies for optimizing a fermentation medium to maximize the yield of a secondary metabolite?

- Problem: The yield of a target metabolite in a fermentation process is suboptimal, and the influence of different medium components is unclear.

- Solution:

- Cause: The type and concentration of carbon and nitrogen sources can exert catabolite repression or other regulatory effects that inhibit secondary metabolite synthesis [32].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Screen Carbon Sources: Replace rapidly metabolized carbon sources (e.g., glucose), which can cause repression, with slowly assimilated ones (e.g., lactose, galactose) that often enhance secondary metabolite production [32].

- Optimize Nitrogen Sources: Identify and optimize the concentration of nitrogen sources, as specific amino acids can either stimulate or inhibit the synthesis of the target metabolite [32].

- Use Statistical Optimization: Employ statistical and mathematical techniques like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) or Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) instead of the classical "one-factor-at-a-time" approach to efficiently navigate the complex interactions between multiple medium components [32] [33].

FAQ 4: My multi-species metabolic model produces thermodynamically infeasible cycles or unrealistic flux distributions. How can I resolve this?

- Problem: Integrated host-microbe or community metabolic models generate predictions that violate thermodynamic laws or are biologically unrealistic.

- Solution:

- Cause: This is often due to inconsistencies when merging models from different sources, such as differing metabolite protonation states, nomenclature, or polymeric compound definitions [31].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Namespace Harmonization: Use standardization resources like MetaNetX to convert all model components (metabolites, reactions) into a unified namespace before integration [31].

- Detect Energy-Generating Cycles: Actively scan the integrated model for cyclic reaction pathways that generate energy or metabolites without inputs, and manually curate or remove them [31].

- Apply Thermodynamic Constraints: Incorporate constraints based on reaction directionality and Gibbs free energy to prevent thermodynamically infeasible flux loops [31].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Reconstruction of a Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GSMM) from an Annotated Genome

Purpose: To create a computational model of an organism's metabolism for FBA simulations [30] [31].

Materials:

- Annotated genome file (e.g., GenBank, GFF format)

- High-performance computing environment

- Metabolic reconstruction software (e.g., mpwt from the metage2metabo suite, CarveMe, RAVEN Toolbox) [30] [31] [34]

- Reference metabolic database (e.g., MetaCyc, KEGG) [30] [34]

Methodology:

- Data Input: Provide the annotated genome as input to the automated reconstruction tool.

- Database Mapping: The tool maps the annotated genes to enzymatic reactions in the reference database (e.g., MetaCyc).

- Network Assembly: The software assembles these reactions into a stoichiometric matrix (S), where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions [1] [31].

- Compartmentalization: For eukaryotic hosts, define different cellular compartments (e.g., mitochondria, cytosol) and assign reactions accordingly [31].

- Biomass Definition: Formulate a biomass reaction that aggregates all essential macromolecules (proteins, lipids, RNA, DNA) in their physiological proportions to represent cellular growth [31].

- Export Model: Convert the reconstructed network into a standard format (e.g., SBML) for use in FBA simulations [34] [35].

Workflow Diagram:

Protocol 2: Performing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) on a GSMM

Purpose: To predict the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network and identify an optimal flux distribution for a given objective [1] [31].

Materials:

- A reconstructed GSMM in SBML format

- Linear programming solver (e.g., GLPK, Gurobi, CPLEX)

- FBA software (e.g., CobraPy in Python, the COBRA Toolbox in MATLAB)

Methodology:

- Define the Problem: Formulate the FBA problem as a linear program using the stoichiometric matrix S and a vector of reaction fluxes, v.

- Apply Steady-State Assumption: Constrain the system so that for all internal metabolites, S · v = 0. This ensures metabolite concentrations remain balanced over time [1].

- Set Flux Boundaries: Define lower and upper bounds (

lb,ub) for each reaction flux (v_i) based on reaction directionality and enzyme capacity [31]. - Define the Objective Function: Select a reaction (or set of reactions) to optimize. This is typically the biomass reaction, formulated as

maximize Z = c^T · v, where c is a vector of weights (usually 1 for the biomass reaction and 0 for others) [1] [31]. - Solve the Linear Program: Use a solver to find the flux distribution v that maximizes (or minimizes) the objective function while satisfying all constraints [1].

- Analyze Output: The solution provides the optimal growth rate and the flux through every reaction in the network under the defined conditions.

Workflow Diagram:

Protocol 3: Building and Simulating a Multi-Species Metabolic Model

Purpose: To investigate metabolic interactions, such as cross-feeding, between different microbial species or a host and its microbiota [31] [34].

Materials:

- Individual GSMMs for all species in the community

- Model integration software or script (e.g., MetaNetX for namespace standardization)

- FBA software capable of handling community models (e.g., Miscoto scopes) [34]

Methodology:

- Model Retrieval/Reconstruction: Obtain or reconstruct high-quality GSMMs for each species using tools like CarveMe or gapseq [31].

- Namespace Standardization: Use a tool like MetaNetX to harmonize metabolite and reaction identifiers across all individual models to ensure consistency [31].

- Model Integration: Create a unified stoichiometric matrix by merging the individual models. A common approach is to create a compartment for each species and add exchange reactions for metabolites that can be shared [31].

- Define Community Objective: The objective function can be tailored, for example, to maximize the total biomass of the community or the biomass of a keystone species [34].

- Simulate and Analyze: Perform FBA on the integrated model. Analyze the flux solution to identify putative metabolic exchanges (cross-feeding) and inter-dependencies [34].

Workflow Diagram:

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 1: Key computational tools and databases for metabolic modeling and fermentation optimization.

| Item Name | Category | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH [30] | Genome Mining Tool | Identifies Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) for secondary metabolites in microbial genomes. |

| CarveMe [30] [31] | Model Reconstruction | An automated tool for reconstructing genome-scale metabolic models from annotated genomes. |

| BiGMeC [30] | Pathway Reconstruction | A bottom-up tool for reconstructing pathways for polyketides (PKs) and nonribosomal peptides (NRPs) from BGCs. |

| COBRA Toolbox [31] | Modeling & Simulation | A MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) of metabolic models, including FBA. |

| CobraPy [1] | Modeling & Simulation | A Python package for constraint-based modeling of metabolic networks, enabling FBA and other analyses. |

| AGORA [31] | Model Repository | A resource of curated, genome-scale metabolic models for hundreds of human gut microbes. |

| MetaCyc [30] [34] | Metabolic Database | A curated database of metabolic pathways and enzymes used as a reference for model reconstruction. |

| MetaNetX [31] | Namespace Standardization | A platform that helps harmonize metabolite and reaction identifiers across different metabolic models and databases. |

| Response Surface Methodology (RSM) [32] [33] | Fermentation Optimization | A statistical technique for modeling and optimizing multiple fermentation medium components simultaneously. |

Data Presentation: Carbon Source Impact on Metabolite Production

Table 2: The effect of different carbon sources on the production of selected secondary metabolites, illustrating carbon catabolite repression. Data adapted from [32].

| Carbon Source | Type | Metabolite | Producer Microorganism | Observed Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Monosaccharide | Penicillin | Penicillium chrysogenum | Repression / Interfering |

| Glucose | Monosaccharide | Actinomycin | Streptomyces sp. | Repression / Interfering |

| Lactose | Disaccharide | Penicillin | Penicillium chrysogenum | Enhanced Production / Non-interfering |

| Lactose | Disaccharide | Erythromycins | Streptomyces erythreus | Enhanced Production / Non-interfering |

| Galactose | Monosaccharide | Penicillin | Penicillium chrysogenum | Repression / Interfering |

| Galactose | Monosaccharide | Actinomycin | Streptomyces antibioticus | Enhanced Production / Non-interfering |

Solving FBA Implementation Hurdles: From Model Debugging to Pathway Balancing Strategies

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Resolving Infeasible FBA Solutions

Q: My Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) model has become infeasible after integrating measured flux values. How can I diagnose and resolve this issue?

Infeasibility occurs when known flux values violate the steady-state or other constraints of your model, rendering no solution possible within the defined bounds [4].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Check for Redundancy and Consistency: Calculate the degrees of redundancy (

degR) using the formuladegR = m - rank(NU), wheremis the number of metabolites andNUis the stoichiometric submatrix for unknown fluxes. A redundant system (degR > 0) may be inconsistent with the measured data [4]. - Identify Conflicting Constraints: Use linear programming (LP) feasibility analysis to pinpoint which fixed flux constraints conflict with the mass balance

Nr = 0and other boundslbi ≤ ri ≤ ubi[4].

Resolution Methods: Apply minimal corrections to the given flux values to achieve feasibility using one of these optimization-based methods:

- Linear Programming (LP) Method: Finds the minimal set of flux corrections (

δ) by minimizing the sum of absolute deviations, suitable for resolving gross errors [4]. - Quadratic Programming (QP) Method: Finds minimal corrections by minimizing the sum of squared deviations, ideal for handling small, normally distributed measurement errors and is equivalent to a weighted least-squares approach [4].

Experimental Protocol: Resolving Infeasibility with Quadratic Programming

- Problem Formulation: Define the QP problem to minimize the correction vector

δ:- Objective:

min δᵀWδ - Constraints:

N(r + δ) = 0andlb ≤ r + δ ≤ ub - Here,

Wis a diagonal weighting matrix, often using the inverse of the measurement variance [4].

- Objective:

- Implementation: Solve the QP using a solver like CPLEX, Gurobi, or the

quadprogfunction in MATLAB. - Validation: Verify that the corrected fluxes

(r + δ)satisfy all model constraints and that the correctionsδare biologically plausible given the experimental context [4].

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Managing Unbounded Fluxes

Q: My FBA solution suggests unrealistically high or infinite fluxes through certain reactions. How can I interpret and bound these fluxes?

Unbounded fluxes indicate directions in the flux space where the solution can extend infinitely without violating constraints, often due to incomplete modeling of cellular limitations [36].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Perform Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): Calculate the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction while achieving optimal objective (e.g., growth). Unbounded fluxes will show an infinite or impractically large range [36].

- Identify Thermodynamic Loops: Check for cyclic sets of reactions that can carry flux without a net change in metabolites, a common source of unbounded solutions.

Resolution Methods:

- Apply the Solution Space Kernel (SSK): The SSK approach identifies a bounded, low-dimensional subset of the solution space that contains the physically meaningful flux variations. It separates unbounded directions as "ray vectors" and focuses analysis on the bounded "kernel" [36].

- Introduce Enzyme Constraints: Cap reaction fluxes based on enzyme availability and their catalytic turnover rates (

kcatvalues). This imposes a physical upper limit on flux [9]. - Add Realistic Reaction Bounds: Incorporate literature-derived or experimentally measured upper and lower bounds for uptake and exchange reactions.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Enzyme Constraints using ECMpy

- Data Curation:

- Split reversible reactions into forward and reverse directions.

- Split reactions with isoenzymes into independent reactions.

- Collect

kcatvalues from the BRENDA database and molecular weights from EcoCyc [9].

- Model Constraining:

- Add a global constraint on the total enzyme pool:

Σ (|vi| / kcat_i) * MW_i ≤ Total_Enzyme_Mass - Here,

viis the flux,kcat_iis the turnover number, andMW_iis the molecular weight of the enzyme catalyzing reactioni[9].

- Add a global constraint on the total enzyme pool:

- Simulation: Perform FBA with the enzyme-constrained model to obtain more realistic, bounded flux distributions.

Troubleshooting Guide 3: Handling Multiple Optimal Solutions

Q: My FBA problem has multiple flux distributions that yield the same optimal objective value (e.g., growth rate). How can I analyze this solution space?

Degeneracy in FBA is common because metabolic networks are typically underdetermined. Analyzing the space of optimal solutions is crucial for robust biological conclusions [37].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): Determine the range of possible fluxes for each reaction within a certain optimality factor (

μ) of the maximum objective valueZ0. Solve the optimization problem:max / min vi- subject to:

Sv = 0,cᵀv ≥ μZ0, andlb ≤ v ≤ ub[37].

- Check Solution Uniqueness: If FVA shows a range of fluxes for many reactions, the solution is degenerate, and the single flux vector from FBA is not unique.

Resolution Methods:

- Lexicographic Optimization: Optimize a series of objectives in a predefined priority order. For example, first maximize biomass, then fix biomass at its optimum and minimize total flux, or maximize/minimize the production of a metabolite of interest [9] [38].

- Use an Improved FVA Algorithm: Reduce computational time by leveraging the basic feasible solution property of LPs. This allows the algorithm to skip redundant optimizations, making comprehensive FVA more efficient for large models [37].

- Solution Space Kernel (SSK) Analysis: Characterize the entire space of optimal solutions by extracting a bounded, low-dimensional kernel. This provides a manageable geometric representation of all possible optimal flux states [36].

Experimental Protocol: Efficient FVA with Solution Inspection

- Initial Optimization: Solve the initial FBA problem to find the maximum objective value

Z0[37]. - Iterative Bound Calculation: For each reaction

i, solve the max and min problems to find its flux range. However, implement a solution inspection step [37]:- After solving any LP, check if the solution

v*has any flux variables at their upper or lower bounds. - If a flux

vjis found at its bound, remove the corresponding FVA problem (max or min forvj) from the queue, as the bound is already known to be attainable.

- After solving any LP, check if the solution

- Output: Report the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction within the optimal solution space. Reactions with zero variability are uniquely determined [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential computational tools and resources for troubleshooting FBA models.

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [39] | A MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling. | Performing FBA, FVA, and many other types of analyses. |

| SSKernel Software [36] | Computes the Solution Space Kernel (SSK) and accompanying ray vectors. | Characterizing bounded, meaningful flux ranges and handling unbounded solutions. |

| ECMpy [9] | A workflow for building enzyme-constrained metabolic models. | Adding realistic flux bounds based on enzyme kinetics and abundance data. |

| BRENDA Database [9] | Curated database of enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat, Km). |

Parameterizing enzyme constraints in metabolic models. |

| FastFVA [37] | A high-performance, parallelized implementation of Flux Variability Analysis. | Rapidly analyzing solution space for large, genome-scale models. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagnostic and Resolution Workflow

This diagram outlines the logical process for diagnosing and resolving the three common FBA pitfalls.

Conceptual Solution Space

This diagram illustrates the concepts of feasible/infeasible solutions, bounded/unbounded fluxes, and multiple optima within the FBA solution space.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental concept behind the bottlenecking-debottlenecking strategy in pathway evolution?

The bottlenecking-debottlenecking strategy is a biofoundry-assisted approach designed to navigate the complex and rugged evolutionary landscapes of multiple pathway enzymes. It first intentionally creates a controlled bottleneck by placing a pathway gene on a low-copy-number plasmid. This constrained environment provides a smoother, more predictable evolutionary trajectory, allowing for the identification of beneficial mutations for that enzyme without causing cellular toxicity or imbalanced flux. Subsequently, this process is repeated for each enzyme in the pathway in a parallel and iterative manner. Once improved variants are identified, the debottlenecking phase begins, where these evolved enzymes are re-assembled into a single, high-activity pathway, often followed by machine learning-aided optimization of gene expression to further balance metabolic flux [40] [41].

Q2: Why is traditional directed evolution often ineffective for optimizing multiple enzymes in a heterologous pathway simultaneously?