Reprogramming Nature's Machinery: A Chemoenzymatic Strategy for Lariat Lipopeptide Biosynthesis

This article explores a groundbreaking chemoenzymatic strategy for synthesizing lariat lipopeptides, a complex class of antimicrobial agents.

Reprogramming Nature's Machinery: A Chemoenzymatic Strategy for Lariat Lipopeptide Biosynthesis

Abstract

This article explores a groundbreaking chemoenzymatic strategy for synthesizing lariat lipopeptides, a complex class of antimicrobial agents. For researchers and drug development professionals, we detail how versatile non-ribosomal peptide cyclases—SurE, WolJ, and TycC thioesterase—can be repurposed through innovative substrate design to overcome traditional synthetic hurdles. The content covers the foundational principles of non-ribosomal peptide synthesis, the methodological breakthrough of stereochemical control and one-pot tandem reactions, optimization for yield and selectivity, and a comparative validation of the platform's efficiency and discovered bioactivities. This paradigm shift enables the modular construction of diverse macrocyclic libraries, directly fueling the discovery of new antibiotic candidates against rising drug-resistant pathogens.

Lariat Lipopeptides: Unveiling Complex Architectures and Biosynthetic Hurdles

Lariat lipopeptides represent a fascinating class of naturally occurring antimicrobial agents characterized by their unique topological architecture. These complex molecules feature a carboxy-terminal macrocyclic "head" group and a long acyl chain appended to an amino-terminal "tail," creating a distinctive lasso-like or lariat-shaped structure [1]. This particular configuration is not merely a structural curiosity but is intimately linked to their biological function, particularly their ability to interact with biological membranes and disrupt microbial cell surfaces [2]. Naturally occurring lariat lipopeptides, such as the clinically significant antibiotics daptomycin (used against severe Gram-positive infections including MRSA) and colistin (a last-line defense against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens), underscore the therapeutic importance of this molecular family [1].

The global rise of antibiotic resistance has intensified the search for novel antimicrobial agents with new modes of action, positioning lariat lipopeptides as promising therapeutic candidates. However, the efficient exploration of their rich chemical space has been persistently hampered by their molecular complexity [1]. The conventional chemical synthesis of these compounds faces substantial challenges, particularly in achieving regioselective macrocyclization, which typically requires orthogonal protecting group strategies and stoichiometric coupling reagents [1]. Furthermore, the dilute conditions needed to suppress intermolecular coupling consume substantial amounts of organic solvents, making production inefficient and environmentally burdensome. It is within this context that innovative biosynthetic approaches, particularly those leveraging non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) and their cyclase domains, have emerged as transformative methodologies for accessing and diversifying these valuable natural products [1] [3].

Structural Topology and Biosynthetic Origins

Defining Structural Characteristics

The lariat lipopeptide family exhibits several defining structural features that differentiate them from other peptide natural products. At their core, they are amphiphilic molecules composed of a hydrophobic fatty acid chain and a hydrophilic peptide moiety [2]. This amphiphilic nature enables their interaction with biological membranes, which is fundamental to their mechanism of action. The characteristic lariat shape arises from a macrocyclic peptide core (the "head") and a linear lipid tail, creating a topology that resembles a lasso [3].

The structural diversity within this family is considerable. The fatty acid chain can vary in length, isomeric form, and saturation degree, and may be further modified through β-hydroxylation, β-amination, or guanylation [2]. The peptide moiety consists of variable sequences incorporating both proteinogenic and non-proteinogenic amino acids, including residues in the D-form, which confer resistance to proteolytic degradation [4]. These peptides can range dramatically in size, with fatty acid chains reported from C7 to C43 and peptide moieties containing anywhere from 2 to 25 amino acid residues [2].

Biosynthesis by Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases

Lariat lipopeptides are primarily synthesized by massive multi-enzyme complexes known as non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) [5]. These enzymatic assembly lines operate through a thiotemplate mechanism that does not rely on ribosomal translation, allowing for the incorporation of diverse non-proteinogenic amino acids and the formation of complex structures [4].

The NRPS machinery is modular in organization, with each module typically responsible for incorporating a single amino acid building block into the growing peptide chain [5]. Each module contains several core domains with distinct catalytic functions:

- Adenylation (A) domains select and activate specific amino acid building blocks as acyl adenylates using ATP [5] [4].

- Peptidyl Carrier Protein (PCP) domains shuttle the activated amino acids and peptide intermediates between catalytic sites using a phosphopantetheine cofactor [5].

- Condensation (C) domains catalyze peptide bond formation between the upstream peptidyl-S-PCP and the downstream aminoacyl-S-PCP [5].

- Thioesterase (TE) domains, located in the final module, catalyze the release of the completed peptide from the NRPS machinery, often through cyclization or hydrolysis [5].

The macrocyclic "head" of lariat lipopeptides is typically constructed by specialized thioesterase domains that catalyze cyclization using side-chain nucleophiles [1]. For lariat-shaped structures, this involves a unique cyclization pattern where the nucleophile is not the N-terminus (as in head-to-tail cyclization) but rather an internal residue, creating the characteristic lariat topology [1].

Table 1: Core Catalytic Domains in Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases

| Domain | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Adenylation (A) Domain | Selects and activates amino acid substrates | Recognizes specific amino acids; uses ATP to form acyl-adenylate intermediate [5] [4] |

| Peptidyl Carrier Protein (PCP) Domain | Shuttles substrates and intermediates | Contains phosphopantetheine cofactor; covalently binds amino acids and peptides via thioester linkage [5] |

| Condensation (C) Domain | Catalyzes peptide bond formation | Forms amide bonds between upstream peptidyl-S-PCP and downstream aminoacyl-S-PCP [5] |

| Thioesterase (TE) Domain | Releases and cyclizes final product | Typically located in terminal module; catalyzes macrocyclization or hydrolysis [1] [5] |

Revolutionary Chemoenzymatic Synthesis Approach

Overcoming Traditional Synthetic Challenges

Traditional chemical synthesis of lariat lipopeptides faces significant obstacles, particularly in achieving regioselective macrocyclization. Conventional approaches require orthogonal protecting group strategies and stoichiometric amounts of coupling reagents, along with dilute conditions to suppress intermolecular side reactions [1]. These requirements make production inefficient, low-yielding, and environmentally taxing, severely hampering structural diversification and exploration of structure-activity relationships.

A groundbreaking study published in Nature Chemistry in 2025 has introduced a transformative chemoenzymatic approach that bypasses these limitations [1] [6]. This methodology repurposes nature's biosynthetic machinery—specifically, non-ribosomal peptide cyclases—by combining enzymatic precision with synthetic flexibility. The strategy involves preparing tailored peptide substrates chemically, then using highly selective enzymatic catalysts to achieve the macrocyclization under mild conditions [1].

Reprogramming Cyclase Specificity Through Substrate Engineering

The key innovation in this approach lies not in engineering the enzymes themselves, but in strategically redesigning their substrates to redirect cyclization specificity [1] [3]. The researchers focused on penicillin-binding protein-type thioesterases (PBP-type TEs), such as SurE and WolJ, which are naturally proficient head-to-tail macrocyclases [3]. These enzymes typically join a peptide's N- and C-termini, forming conventional cyclic peptides rather than lariat structures.

To redirect this activity toward lariat formation, the researchers engineered branched peptide substrates containing a "pseudo-N-terminus"—a dipeptide unit featuring an additional N-terminus within a peptide side chain [1] [3]. This design creates two potential nucleophilic sites for cyclization: the native N-terminus and the pseudo-N-terminus. When the native N-terminus had an L-configured amino acid, SurE produced both the conventional head-to-tail macrocycle and the lariat-shaped peptide in comparable amounts (60% and 40% respectively), demonstrating that the pseudo-N-terminus could serve effectively as a nucleophile [1].

Stereochemical Control for Exclusive Lariat Formation

To achieve exclusive lariat formation, the researchers implemented a stereochemical switching strategy [1] [3]. They exploited the fact that PBP-type TEs strictly recognize the stereochemical configuration of nucleophiles, accepting only L-configured residues while rejecting D-configured ones. By replacing the native N-terminal L-amino acid with its D-configured counterpart, they effectively blocked the head-to-tail cyclization pathway. This forced the enzyme to use exclusively the pseudo-N-terminus (with its L-configured residue) as the nucleophile, resulting in quantitative production of the lariat-shaped cyclic peptide with complete regiospecificity [1].

This strategy demonstrated remarkable generality, working effectively with multiple macrocyclases including SurE, WolJ (both PBP-type TEs), and TycC-TE (a type-I thioesterase) [1] [3]. The ability to repurpose different cyclases through substrate design alone, without protein engineering, significantly expands the synthetic toolbox available for lariat lipopeptide production.

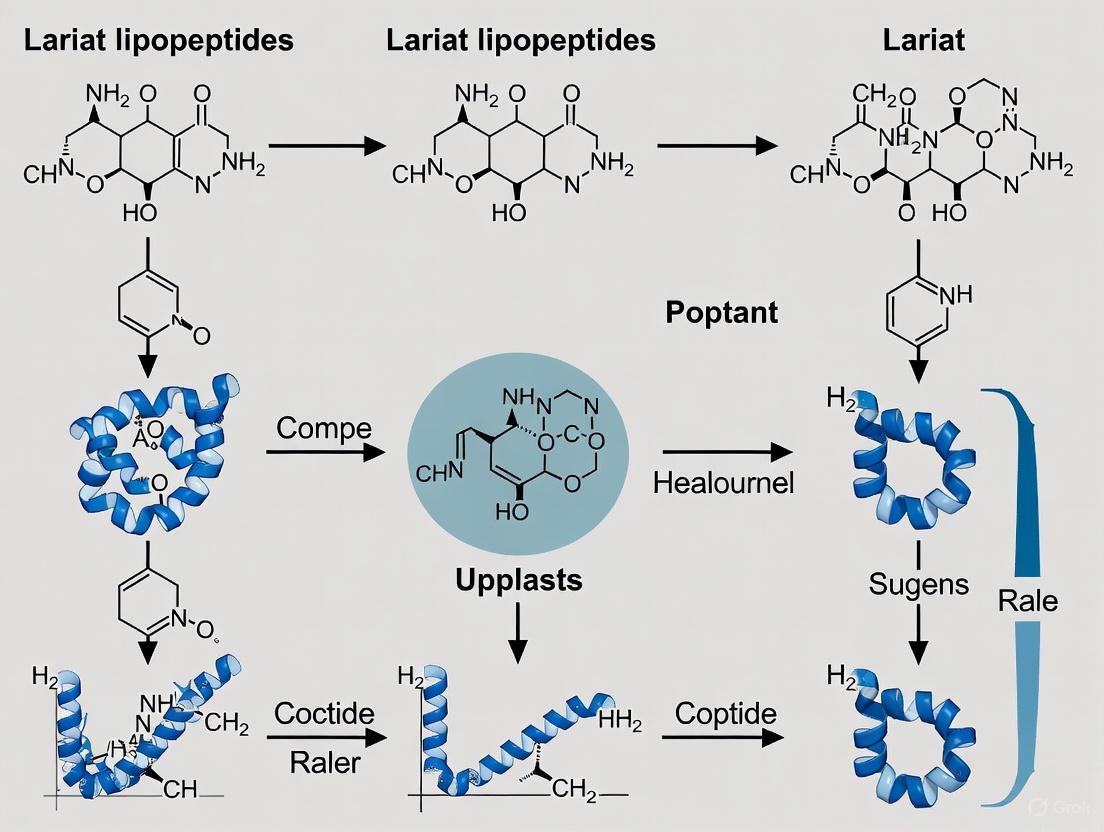

Diagram 1: Stereochemical Control of Lariat Cyclization

Tandem Cyclization-Aylation Strategy

A particularly innovative aspect of this methodology is the development of a one-pot tandem cyclization-acylation process [1] [3]. After enzymatic macrocyclization, the remaining nucleophile (the one not used in cyclization) serves as a reactive handle for subsequent diversification via site-selective Ser/Thr ligation (STL). This enables the direct attachment of various acyl groups to create the characteristic lipophilic "tail" of lariat lipopeptides.

This sequential one-pot approach eliminates the need for intermediate purification and enables efficient parallel synthesis of diverse lariat lipopeptide libraries [3]. The ability to perform both cyclization and acylation under mild conditions in a single pot represents a significant streamlining of the synthetic workflow, facilitating rapid generation of structural diversity for biological evaluation.

Table 2: Key Enzymes in Chemoenzymatic Lariat Synthesis

| Enzyme | Classification | Role in Synthesis | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| SurE | Penicillin-Binding Protein-type Thioesterase (PBP-type TE) | Macrocyclization catalyst | Broad substrate tolerance; strictly accepts only L-configured nucleophiles [1] [3] |

| WolJ | Penicillin-Binding Protein-type Thioesterase (PBP-type TE) | Macrocyclization catalyst | Functions similarly to SurE; demonstrates versatility in lariat formation [1] |

| TycC Thioesterase (TycC-TE) | Type-I Thioesterase | Macrocyclization catalyst | Originally a head-to-tail cyclase; repurposed for lariat synthesis [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Substrate Design and Synthesis

The synthesis of branched peptide substrates begins with solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) on a resin functionalized with ethylene glycol (EG), which serves as a simplified surrogate for the natural pantetheine leaving group [1]. This design simplifies substrate synthesis and streamlines the overall process. The peptide main chain is assembled using standard SPPS protocols, with the incorporation of an L-lysine residue at the intended branching point. This lysine side chain is protected with an orthogonal 1-(4,4-dimethyl-2,6-dioxocyclohex-1-ylidene)ethyl (Dde) protecting group.

After assembly of the linear sequence, the Dde protecting group is selectively removed using 2% hydrazine, exposing the ε-amino group of lysine. The pseudo-N-terminal dipeptide unit is then installed on this side chain through additional coupling cycles. Finally, resin cleavage and global deprotection yield the ethylene glycol-functionalized branched peptide substrate ready for enzymatic cyclization [1].

Enzymatic Macrocyclization Protocol

The enzymatic macrocyclization is performed under mild, aqueous conditions. The branched peptide substrate (typically at concentrations of 0.5-1.0 mM) is incubated with the selected cyclase enzyme (SurE, WolJ, or TycC-TE) at a catalytic loading of 5 mol% in an appropriate buffer system [1]. The reaction proceeds at 30°C with gentle agitation for several hours. Reaction progress is monitored by LC-MS until complete consumption of the starting material is observed.

For the stereochemically controlled exclusive lariat formation, the substrate features a D-configured amino acid at the native N-terminus and an L-configured amino acid at the pseudo-N-terminus. This configuration ensures that only the pseudo-N-terminus can serve as the nucleophile for cyclization, resulting in quantitative conversion to the lariat product without formation of head-to-tail byproducts [1].

One-Pot Tandem Cyclization-Acylation

The tandem process begins with the enzymatic macrocyclization as described above. Upon completion of cyclization (typically within 3 hours), the reaction mixture is directly subjected to Ser/Thr ligation without intermediate purification [1]. The site-selective acylation targets the free N-terminus not used in the cyclization process, allowing attachment of various lipid tails under mild conditions compatible with the aqueous enzymatic reaction.

This streamlined approach enables the rapid generation of diverse lariat lipopeptide libraries. The resulting compounds can be directly screened for biological activity without extensive purification, significantly accelerating the discovery process [1] [3].

Diagram 2: Chemoenzymatic Synthesis Workflow

Therapeutic Significance and Biological Activity

Antimicrobial Properties and Mechanisms

Lariat lipopeptides exhibit potent antimicrobial activity through diverse mechanisms, primarily targeting bacterial cell surfaces [3]. Their amphiphilic structure enables interaction with biological membranes, leading to disruption of membrane integrity or interference with essential membrane-associated processes [2]. Different lipopeptides may target specific components of microbial membranes, with some acting on cell wall biosynthesis through complex formation with bactoprenol phosphate, while others directly disrupt membrane integrity [7].

The unique lariat topology appears to optimize these interactions, positioning the macrocyclic head for specific molecular recognition while the lipid tail embeds within membrane environments. This structural arrangement often results in selective toxicity toward microbial cells over mammalian cells, though this varies considerably with specific structural features [2].

Antimycobacterial Activity of Synthetic Variants

Biological screening of the lariat lipopeptide library generated through the chemoenzymatic approach revealed significant antimycobacterial activity [1] [7]. Several compounds demonstrated potent inhibition of Mycobacterium intracellulare growth, with half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) ranging from 8-16 µg/ml [1]. This activity is particularly valuable given the rising concerns about drug-resistant mycobacterial infections, including tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial diseases.

The screening identified eight particularly promising compounds that effectively inhibited M. intracellulare growth at these low concentrations [1]. Importantly, the site-selective acylation strategy was found to be crucial for conferring this antimycobacterial activity, as the specific nature and positioning of the lipid tail dramatically influenced both potency and selectivity [1].

Antiviral Activity and Structure-Activity Relationships

Beyond antibacterial applications, lipopeptides also demonstrate significant antiviral potential, particularly against enveloped viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 [2]. Studies have shown that certain lipopeptides can reduce SARS-CoV-2 RNA to undetectable levels at concentrations of 100 µg/ml, with surfactin, WLIP, fengycin, and caspofungin emerging as particularly promising anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents [2].

These lipopeptides appear to target multiple stages of the viral life cycle that involve the viral envelope. Surfactin and WLIP significantly reduce viral RNA levels in replication assays, comparable to neutralizing serum, while surfactin uniquely inhibits viral budding, and fengycin impacts viral binding after pre-infection treatment of cells [2]. Structure-activity relationship studies have identified that lipopeptides with a high number of amino acids, particularly those with charged (preferentially anionic) amino acids, tend to exhibit the most potent anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity with lower cytotoxicity [2].

Table 3: Biological Activities of Representative Lipopeptides

| Lipopeptide | Primary Activity | Reported Efficacy | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daptomycin | Antibacterial (Gram-positive) | Clinical use against MRSA | Disrupts bacterial membrane potential; inhibits cell wall synthesis [1] |

| Colistin | Antibacterial (Gram-negative) | Last-line defense drug | Binds to LPS, disrupts outer membrane [1] |

| Surfactin | Antiviral (SARS-CoV-2) | Reduces viral RNA to undetectable levels at 100 µg/mL [2] | Multiple mechanisms: reduces viral RNA, inhibits budding [2] |

| Chemoenzymatic Variants | Antimycobacterial | IC50 8-16 µg/mL against M. intracellulare [1] | Membrane disruption; precise mechanism under investigation [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The chemoenzymatic synthesis of lariat lipopeptides requires specialized reagents and materials that enable this sophisticated approach. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for implementing these methodologies.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Lariat Lipopeptide Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| PBP-type Thioesterases (SurE, WolJ) | Macrocyclization catalysts | Recombinantly expressed; 5 mol% catalytic loading; strict L-nucleophile specificity [1] [3] |

| Type-I Thioesterase (TycC-TE) | Alternative macrocyclization catalyst | Broad substrate tolerance; repurposable for lariat synthesis [1] |

| Ethylene Glycol (EG)-Functionalized Resin | Solid support for SPPS | Simplifies substrate synthesis; surrogate for pantetheine leaving group [1] |

| Dde-Protected Lysine | Orthogonal protection for branching point | Allows selective deprotection with 2% hydrazine for pseudo-N-term installation [1] |

| Ser/Thr Ligation (STL) Reagents | Site-selective acylation | Enables lipid tail attachment to free N-terminus in one-pot procedure [1] |

| H-DL-Glu(Ome)-OMe.HCl | H-DL-Glu(Ome)-OMe.HCl, CAS:23150-65-4, MF:C7H14ClNO4, MW:211.64 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| D,L-Tryptophanamide hydrochloride | D,L-Tryptophanamide hydrochloride, CAS:67607-61-8, MF:C11H14ClN3O, MW:239.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The structural topology of lariat lipopeptides—characterized by their macrocyclic head and linear lipid tail—confers unique biological properties that make them valuable therapeutic candidates, particularly in an era of escalating antimicrobial resistance. The development of innovative chemoenzymatic synthesis methodologies represents a paradigm shift in our ability to access and diversify these complex natural products.

By repurposing versatile non-ribosomal peptide cyclases through strategic substrate design rather than protein engineering, researchers have overcome long-standing synthetic challenges. The implementation of stereochemical control to switch cyclization specificity, coupled with tandem cyclization-acylation in one pot, enables efficient generation of diverse lariat lipopeptide libraries for biological evaluation. These advances have already yielded promising compounds with potent antimycobacterial activity and revealed structure-activity relationships that can guide future design.

Looking forward, this chemoenzymatic platform offers exciting opportunities for further innovation. The directed evolution of peptide cyclases could expand substrate scope and enhance catalytic efficiency, while incorporation of non-natural amino acids or chemically modified lipids could dramatically enrich structural diversity. As the threat of antimicrobial resistance intensifies, such advanced synthetic strategies will become increasingly critical for developing the next generation of therapeutic agents. The integration of nature's catalytic precision with synthetic ingenuity, as demonstrated in the synthesis of lariat lipopeptides, provides a powerful blueprint for future natural product-based drug discovery.

The Role of Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS) in Natural Biosynthesis

Non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) represent a class of massive modular enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of structurally and functionally diverse peptide secondary metabolites independently of the ribosomal machinery [8]. These enzymatic assembly lines are primarily found in bacteria and fungi and are responsible for producing numerous pharmacologically active compounds, including antibiotics (e.g., penicillin, vancomycin), immunosuppressants (e.g., cyclosporine), and anticancer agents [5] [9]. Unlike ribosomally synthesized peptides, non-ribosomal peptides (NRPs) often feature complex structures including cyclic, branched, or linear architectures; incorporate non-proteinogenic amino acids (e.g., D-amino acids, N-methylated amino acids); and contain various modifications such as glycosylation, acylation, and halogenation [10] [8]. This chemical diversity, inaccessible to ribosomal synthesis, underpins the broad biological activities of NRPs and their importance in drug discovery [9].

The biosynthesis of lariat lipopeptides represents a particularly sophisticated application of NRPS machinery. These compounds, exemplified by important antimicrobial agents like daptomycin and colistin, feature a carboxy-terminal macrocyclic "head" group and a long acyl chain appended to an amino-terminal "tail" [1]. Their complex lariat-shaped topologies have posed significant challenges for chemical synthesis, hampering efficient structural diversification for drug development [1] [3]. Recent advances in understanding NRPS cyclization mechanisms, particularly through the repurposing of non-ribosomal peptide cyclases, have opened new avenues for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of these valuable compounds, demonstrating the continued relevance of NRPS systems in addressing modern antibiotic resistance challenges [1] [3].

NRPS Modular Architecture and Domain Organization

Core Domains and Their Functions

NRPSs exhibit a modular organization where each module is responsible for incorporating one monomeric building block into the growing peptide chain. Each module contains three core catalytic domains that work in concert to activate, carry, and connect amino acid substrates [5] [9].

Table 1: Core Domains in Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases

| Domain | Abbreviation | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenylation Domain | A | Selects and activates amino acid substrates using ATP | Forms aminoacyl-AMP intermediate; determines substrate specificity [5] |

| Peptidyl Carrier Protein | PCP | Carries activated amino acids and peptide intermediates | Contains 4'-phosphopantetheine prosthetic group; swivels between domains [5] |

| Condensation Domain | C | Catalyzes peptide bond formation between donor and acceptor substrates | Contains HHxxxDG catalytic motif; exhibits substrate gating function [11] [9] |

| Thioesterase Domain | TE | Releases full-length peptide from NRPS assembly line | Catalyzes hydrolysis or cyclization; often forms macrocyclic structures [12] [5] |

The adenylation (A) domain belongs to the ANL superfamily of adenylating enzymes and performs the critical first step of substrate recognition and activation [5]. Using ATP, it catalyzes the formation of an aminoacyl-adenylate mixed anhydride, which then gets loaded onto the thiol group of the 4'-phosphopantetheine (PPant) arm attached to the peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) domain [5] [9]. The PCP domain serves as a flexible swivel arm, shuttling the covalently tethered substrates between different catalytic sites [5]. The condensation (C) domain catalyzes the central chemical step of peptide bond formation, facilitating nucleophilic attack by the α-amino group of the downstream ("acceptor") aminoacyl-PCP on the upstream ("donor") peptidyl-PCP thioester [11] [9]. In the termination module, the thioesterase (TE) domain mediates product release, often through hydrolysis or intramolecular cyclization, the latter being particularly relevant for generating macrocyclic scaffolds found in lariat lipopeptides [1] [12].

Modular Organization and Assembly Line Logic

NRPSs are organized as sequential modules, with the number and order of modules typically correlating with the sequence of the final peptide product [9]. A minimal elongation module contains C-A-PCP domains, while the initiation module often lacks the C domain, and the termination module contains additional domains like TE for product release [5] [8]. This assembly line logic enables the coordinated elongation of the peptide chain, with each module incorporating one specific monomer before passing the growing chain to the next module [9].

Table 2: Optional Modification Domains in NRPS Systems

| Domain | Abbreviation | Function | Structural Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epimerization Domain | E | Converts L-amino acids to D-amino acids | Incorporates D-configured residues [8] |

| N-Methyltransferase Domain | NMT | Adds methyl groups to amino groups | Creates N-methylated peptides [8] |

| Cyclization Domain | Cy | Catalyzes heterocyclization of Cys/Ser/Thr | Forms thiazoline/oxazoline rings [8] |

| Oxidation Domain | Ox | Oxidizes heterocycles to aromatic forms | Converts thiazolines to thiazoles [8] |

| Reduction Domain | R | Reduces terminal thioester to aldehyde/alcohol | Creates peptide aldehydes/alcohols [8] |

Figure 1: NRPS Modular Organization and Assembly Line Logic

Structural and Mechanistic Insights into NRPS Domains

Condensation Domain: The Peptide Bond Formation Catalyst

The condensation (C) domain serves as the central catalyst for amide bond formation in NRPS systems. Structural studies have revealed that C domains typically consist of approximately 450 amino acids and adopt a pseudo-dimeric chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) fold, composed of two similar subdomains at the N- and C-termini [11] [9]. Between the interfaces of these subdomains, a cleft forms that accommodates the donor and acceptor Ppant arms, which must access the conserved active site motif HHxxxDG located in the N-terminal subdomain [9].

Structural characterization of C domain complexes has provided crucial insights into their mechanism of action. The structure of the PCP2-C3 didomain from the fuscachelin NRPS of Thermobifida fusca revealed that the interface between the PCP and C domains is dominated by hydrophobic interactions, with key residues from both domains mediating this interaction [11]. Access to the C domain active site appears to be gated by an arginine residue (R2906) that helps position the PCP domain and likely prevents unloaded PCP substrates from accessing the active site [11].

The precise catalytic mechanism of C domains remains partially unresolved. While the second histidine in the HHxxxDG motif was initially proposed to act as a catalytic base that deprotonates the α-amino group of the acceptor substrate, mutation studies have shown that this residue is not always essential for activity [9]. Alternative hypotheses suggest this histidine may instead function in positioning the acceptor substrate or stabilizing the transition state [9]. Beyond catalysis, C domains play a crucial role as secondary gatekeepers for substrate specificity, providing a proofreading function that significantly reduces error rates in monomer incorporation [9].

Thioesterase Domains and Cyclization Mechanisms

Thioesterase (TE) domains perform the critical terminal step in NRPS synthesis by releasing the full-length peptide from the assembly line. These domains typically adopt an α/β-hydrolase fold and contain a distinctive bowl-shaped hydrophobic cavity that hosts the acylpeptide substrate and accommodates its folding into cyclic structures [12]. Two major classes of TEs have been identified in NRPS systems: type I TEs (α/β-hydrolase type) and the more recently discovered penicillin-binding protein (PBP)-type TEs [1] [3].

In lariat lipopeptide biosynthesis, TE domains catalyze intramolecular cyclization to form macrolactam rings. Traditional lariat-forming type I TEs typically utilize side chain nucleophiles for cyclization but are often sensitive to changes in the local environment of the nucleophilic residue, limiting their utility for generating diverse lariat peptides [1]. In contrast, PBP-type TEs such as SurE and WolJ demonstrate broader substrate tolerance and have been repurposed for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of lariat peptides through strategic substrate redesign [1] [3].

Structural studies of TE domains, such as the excised 28 kDa SrfTE domain from surfactin synthetase, have revealed how the hydrophobic cavity hosts the acylpeptide substrate and facilitates its folding into cyclic structures [12]. Docking studies with the peptidyl carrier protein domain immediately preceding SrfTE have shown how the 4'-phosphopantetheinyl prosthetic group positions the nascent acyl-peptide chain for transfer to the TE domain [12].

Experimental Approaches in NRPS Research

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Lariat Lipopeptides

Recent groundbreaking work has demonstrated the repurposing of head-to-tail NRP cyclases for lariat peptide synthesis through strategic substrate engineering rather than protein engineering [1] [3]. The key innovation involves introducing an internal dipeptide unit as a "pseudo-N terminus," where an L-Ile residue is attached to the side chain of L-Lys via an isopeptide bond, creating a branched substrate with two potential nucleophiles for cyclization [1]. When incubated with the PBP-type TE SurE, this branched substrate is converted into both canonical head-to-tail cyclic peptides and lariat-shaped cyclic peptides in comparable amounts [1].

To achieve exclusive lariat formation, researchers exploited the stereospecificity of PBP-type TEs, which accept only L-configured residues as nucleophiles [1] [3]. By replacing the native N-terminal L-Ile residue with D-Val, head-to-tail cyclization was suppressed, forcing the enzyme to use the pseudo-N-terminal L-Ile as the nucleophile and quantitatively producing lariat-shaped cyclic peptides [1]. This strategy demonstrated remarkable regioselectivity, as substrates containing three different nucleophiles (N-terminal D-Val, pseudo-N-terminal L-Ile, and ε-NH₂ of L-Lys) cyclized exclusively via the pseudo-N-terminal L-Ile [1].

Table 3: Experimental Results for SurE-Catalyzed Lariat Peptide Synthesis

| Substrate | N-terminal Configuration | Products Generated | Yield | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branched substrate 1 | L-Ile (native) | Head-to-tail cyclic (2) + Lariat cyclic (3) | 60% + 40% | Pseudo-N-terminus as effective nucleophile [1] |

| Branched substrate 4 | D-Val (modified) | Lariat cyclic (5) only | Quantitative | Complete regiospecificity for lariat formation [1] |

| Substrates 6-11 | D-Val with varied pseudo-N terminus positions | Lariat peptides with different ring sizes | Varied | Tolerance for different pseudo-N terminus positions [1] |

The tandem cyclization-acylation strategy enables one-pot, modular synthesis of lariat-shaped lipopeptides equipped with various acyl groups [1]. This approach facilitated the creation of a 51-member library of lariat lipopeptides that could be directly screened for antimicrobial activity, leading to the identification of compounds that inhibit Mycobacterium intracellulare growth by 50% at concentrations of 8-16 μg mlâ»Â¹ [1] [3].

Figure 2: Chemoenzymatic Synthesis Workflow for Lariat Lipopeptides

Structural Biology Techniques for NRPS Characterization

Structural characterization of NRPS domains and complexes has been instrumental in understanding their mechanisms. X-ray crystallography has provided high-resolution structures of individual domains, including adenylation domains, condensation domains, peptidyl carrier proteins, and thioesterase domains [11] [12] [5]. The crystallization of didomain constructs, such as PCP-C and A-PCP complexes, has offered insights into interdomain interactions and conformational dynamics [11] [5].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have complemented experimental structural data by providing dynamic information about substrate-enzyme interactions. In studies of SurE-catalyzed lariat peptide formation, MD simulations of covalent docking models constructed using the crystal structure of apo SurE revealed that L-Ile nucleophiles are retained in the nucleophile binding site with an average distance of 4.5 Ã… from the C-terminal carbonyl carbon, while D-configured nucleophiles exhibit positional variability with much longer distances (>10 Ã…), explaining the observed stereospecificity [1].

Mechanism-based inhibitors have been particularly valuable for trapping transient interactions between catalytic and carrier protein domains [5]. For example, the use of stable analogs of acyl acceptor substrates complexed to C domains has enabled structural characterization of these typically dynamic complexes [11]. Similarly, the formation of crosslinked domains using mechanism-based inhibitors has facilitated crystallization of meta-stable intermediates along the catalytic pathway [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for NRPS Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for NRPS Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| EG-functionalized Resins | Solid-phase synthesis of peptide substrates with C-terminal ethylene glycol leaving group | Wang resin derivatives with ethylene glycol linkers | Simplifies enzymatic substrate synthesis; streamlines process [1] |

| PBP-type Thioesterases | Enzymatic macrocyclization of linear peptide substrates | SurE, WolJ | Broad substrate tolerance; 5 mol% catalyst loading; quantitative yields [1] [3] |

| Type I Thioesterases | Comparative cyclization studies; lariat formation | TycC thioesterase | Demonstrated adaptability to lariat synthesis via substrate engineering [1] |

| Stable Acyl-CoA Analogs | Investigation of C domain specificity and PCP interactions | Aminoacyl-coenzyme A analogs | Bypasses A domain selectivity; allows direct C domain specificity studies [9] |

| Mechanism-based Inhibitors | Trapping domain interactions for structural studies | Crosslinking analogs of aminoacyl-AMP | Enables crystallization of transient complexes [5] |

| MbtH-like Proteins | Activation of A domains in certain NRPS systems | Various MbtH homologs | Required for activity of some A domains; essential cofactor [8] |

| Phosphopantetheinyl Transferases | Conversion of apo- to holo-PCP domains | Sfp from B. subtilis | Broad substrate specificity; essential for in vitro reconstitution [9] |

Applications and Future Directions in NRPS Engineering

Genome Mining for Novel NRPS Discovery

Bioinformatics approaches have revolutionized the discovery of novel NRPS systems through genome mining. Analysis of 123 complete genomes of Bacillus strains isolated from soil and fermented foods using antiSMASH version 7 revealed that 83% possess biosynthetic gene clusters for siderophore bacillibactin, 61% for surfactins, 37% for fengycins, 23% for iturins, 15% for kurstakins, and 3% for bacitracin [13]. Importantly, this study identified seven novel biosynthetic gene clusters coding NRPSs in various Bacillus strains, demonstrating the significant potential of genome mining strategies for discovering new metabolites [13].

Computational tools have been developed to predict substrate specificity from DNA or protein sequence data, with methods such as SANDPUMA and NRPSpredictor2 enabling researchers to identify the likely products of NRPS clusters directly from genomic information [8]. These approaches have accelerated the discovery of novel nonribosomal peptides and facilitated the prioritization of clusters for experimental characterization.

Engineering Strategies for Novel Peptide Production

NRPS engineering holds tremendous promise for generating novel peptides with tailored properties. The modular architecture of NRPS systems theoretically allows for the creation of hybrid assembly lines through domain or module swapping [10] [9]. Successful examples include the engineering of surfactin and daptomycin synthetases to produce analogs with modified amino acid composition [10].

Rational protein design has yielded methodologies to computationally switch the specificities of A-domains, with ten amino acids identified that control substrate specificity and can be considered the 'codons' of nonribosomal peptide synthesis [8]. Engineering of C domains has proven more challenging due to their complex structure and dual donor-acceptor selectivity, but progress in understanding C domain structure and mechanism is gradually enabling more targeted engineering approaches [9].

The chemoenzymatic approach to lariat lipopeptide synthesis represents a particularly promising direction for NRPS engineering. By combining enzymatic cyclization with chemical diversification, this strategy leverages the efficiency and selectivity of enzymatic transformations while enabling modular access to diverse compound libraries [1] [3]. The ability to perform cyclization and acylation reactions sequentially in a single pot without intermediate purification significantly streamlines the synthesis workflow and enables rapid generation of libraries for biological screening [1].

As structural and mechanistic understanding of NRPS systems continues to advance, and as tools for manipulating these complex enzymes improve, the potential for engineering NRPSs to produce novel therapeutic compounds continues to expand. The integration of computational design, structural biology, and synthetic biology approaches promises to unlock the full potential of these remarkable molecular assembly lines for drug discovery and development.

The Emergence of Non-Ribosomal Peptide Cyclases as Biocatalytic Tools

Non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) represent nature's sophisticated molecular assembly lines for producing structurally complex peptides with valuable biological activities, including antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and anticancer agents [9] [14]. These massive multi-modular enzymes activate, incorporate, and join amino acid building blocks in an assembly-line fashion, with the final product release often catalyzed by specialized thioesterase (TE) domains that can hydrolyze or cyclize the fully assembled peptide chain [5] [12]. For decades, scientists have recognized the potential of harnessing these enzymatic machineries for synthetic biology and drug development, particularly for generating complex cyclic peptide architectures that are challenging to produce using conventional chemical methods [9].

The global health crisis of antimicrobial resistance has intensified the search for new antibiotics with novel mechanisms of action, bringing lariat lipopeptides into sharp focus [1] [3]. These naturally occurring compounds, exemplified by clinically important drugs like daptomycin and colistin, feature a unique topology consisting of a carboxy-terminal macrocyclic "head" group and a long acyl chain appended to an amino-terminal "tail" [1]. This lariat configuration enables diverse modes of action, primarily targeting bacterial cell surfaces, which reduces the likelihood of cross-resistance with conventional antibiotics [1]. However, the efficient exploration of this rich chemical space has been hampered by significant synthetic challenges. Traditional chemical synthesis of lariat-shaped lipopeptides requires orthogonal protecting group strategies, stoichiometric coupling reagents, and dilute conditions to suppress intermolecular side reactions, resulting in substantial organic solvent waste and limited scalability [1].

This technical guide examines the emerging paradigm shift in which non-ribosomal peptide cyclases are being repurposed as versatile biocatalytic tools to overcome these synthetic limitations, with particular emphasis on recent breakthroughs in chemoenzymatic synthesis of lariat lipopeptides.

Fundamental NRPS Architecture and Cyclization Mechanisms

Core Domains and Their Functions

Non-ribosomal peptide synthetases employ a modular architecture where each module is responsible for incorporating a single amino acid residue into the growing peptide chain [9]. A minimal elongation module contains three core domains:

- Adenylation (A) domain: Selects and activates specific amino acid substrates through ATP-dependent adenylation [5] [9]

- Peptidyl Carrier Protein (PCP) domain: Shuttles the activated amino acids and peptide intermediates between catalytic domains using a 4'-phosphopantetheine (Ppant) prosthetic group [5]

- Condensation (C) domain: Catalyzes peptide bond formation between the upstream donor and downstream acceptor substrates [9]

The thioesterase (TE) domain, located at the C-terminus of the terminal module, is particularly relevant to cyclization processes. This domain catalyzes the release of the fully assembled peptide from the NRPS machinery through hydrolysis or, more commonly, intramolecular cyclization [5] [12]. TE domains belong to the α/β-hydrolase fold family and typically feature a distinctive bowl-shaped hydrophobic cavity that hosts the acylpeptide substrate and accommodates its folding into a cyclic structure [12].

Structural Basis of Cyclization

Structural studies of NRPS components have revealed critical insights into the cyclization mechanism. The excised 28 kDa SrfA-C thioesterase domain, for instance, exhibits a hydrophobic cavity that positions the peptide substrate for macrocyclization [12]. Docking studies with the peptidyl carrier protein domain immediately preceding the TE domain show how the 4'-phosphopantetheinyl prosthetic group transfers the nascent acyl-peptide chain to the TE active site [12].

The catalytic triad of TE domains (typically serine-histidine-aspartate) first catalyzes the transfer of the peptide from the PCP-bound thioester to an active site serine, forming an acyl-enzyme intermediate. The peptide then folds into a conformation that allows a nucleophilic attack from an internal residue (amine or hydroxyl group), resulting in macrocyclization and product release [12].

Figure 1: Catalytic Cycle of NRPS Thioesterase Domains in Peptide Cyclization

Breaking the Specificity Barrier: Reprogramming Cyclases for Lariat Peptide Synthesis

The Substrate Engineering Breakthrough

Historically, application of lariat-forming TE domains in biocatalysis has been limited by their narrow substrate specificity and sensitivity to changes in the local environment of the nucleophilic residue [1]. However, a groundbreaking approach reported in 2025 has circumvented these limitations through creative substrate design rather than extensive enzyme engineering [1] [3].

The key innovation involves introducing a "pseudo-N-terminus" – a dipeptide unit featuring an additional N-terminus within the peptide side chain – creating two possible nucleophilic sites for cyclization [1] [3]. When the branched substrate was incubated with SurE, a penicillin-binding protein-type thioesterase, the enzyme generated both canonical head-to-tail cyclic peptides and lariat-shaped cyclic peptides in comparable amounts (60% and 40% respectively), demonstrating that the pseudo-N-terminus could serve as an effective nucleophile for cyclization [1].

Stereochemical Control for Regioselective Cyclization

To achieve exclusive lariat peptide formation, researchers implemented a stereochemical switching strategy. Building on the knowledge that PBP-type TEs strictly recognize the stereochemical configuration of nucleophiles (accepting only l-configured residues, not d-configured ones), the native N-terminal residue was replaced with its mirror-image d-amino acid [1] [3]. This simple but elegant modification effectively suppressed head-to-tail cyclization while forcing the enzyme to use the pseudo-N-terminus as the nucleophile, yielding lariat peptides with complete selectivity [1].

Molecular dynamics simulations provided structural insights into this stereochemical control mechanism. When an l-configured nucleophile was positioned in the nucleophile binding site, it remained stably positioned with the nucleophilic amine approximately 4.5 Ã… from the C-terminal carbonyl carbon [1]. In contrast, d-configured nucleophiles exhibited positional variability with much longer distances to the electrophilic carbon (>10 Ã…), explaining their inability to participate efficiently in cyclization [1].

Table 1: Key Non-Ribosomal Peptide Cyclases Used in Lariat Lipopeptide Synthesis

| Enzyme | Class | Natural Specificity | Engineered Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SurE | PBP-type TE | Head-to-tail cyclization | Lariat cyclization | Broad substrate tolerance, strict l-nucleophile specificity |

| WolJ | PBP-type TE | Head-to-tail cyclization | Lariat cyclization | Similar to SurE, compatible with diverse sequences |

| TycC-TE | Type I TE | Head-to-tail cyclization | Lariat cyclization | α/β-hydrolase fold, processes decapeptidyl substrates |

Experimental Framework: Methodologies for Chemoenzymatic Lariat Synthesis

Substrate Design and Synthesis Protocol

The synthesis of branched peptide substrates for lariat cyclization involves these key steps:

Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS): Peptide main chains are synthesized on a solid support functionalized with ethylene glycol (EG), which serves as a simplified surrogate for the natural pantetheine leaving group, significantly streamlining the synthetic process [1].

Orthogonal Protection Strategy: An orthogonal protecting group (1-(4,4-dimethyl-2,6-dioxocyclohex-1-ylidene)ethyl, Dde) on the l-Lys side chain enables selective deprotection using 2% hydrazine [1].

Pseudo-N-Terminus Installation: Following Dde removal, the pseudo-N-terminal amino acid (e.g., l-Ile) is coupled to the side chain of l-Lys via an isopeptide bond in an additional round of coupling [1].

Global Deprotection and Cleavage: Resin cleavage with concomitant global deprotection generates the ethylene glycol-functionalized branched peptide ready for enzymatic cyclization [1].

This synthetic approach demonstrates significant advantages over traditional methods. For instance, the lariat peptide 5 could be obtained by chemical synthesis in 19 steps with a yield of 33%, while the corresponding EG substrate 4 was obtained in 17 steps with an 83% yield, followed by quantitative cyclization using SurE [1].

Enzymatic Cyclization and One-Pot Diversification

The core enzymatic cyclization process follows this optimized protocol:

Reaction Conditions: Branched EG-functionalized substrate (e.g., compound 4) is incubated with 5 mol% SurE at 30°C for 3 hours [1].

Real-Time Monitoring: Reaction progress is monitored by LC-MS to confirm complete substrate conversion, typically achieving quantitative yields for optimized substrates [1].

Product Characterization: Tandem mass spectrometry (MS²) verifies the cyclic structure and differentiates between head-to-tail and lariat cyclization products based on fragmentation patterns [1].

For generating pharmaceutically relevant lariat lipopeptides, researchers developed a tandem cyclization-acylation strategy that combines enzymatic macrocyclization with serine/threonine ligation (STL) in a single pot [1] [3]. This approach exploits the remaining nucleophile (not involved in cyclization) as a reactive handle for site-selective acylation with various lipid chains, which are essential for biological activity [1]. The one-pot process eliminates intermediate purification and enables efficient parallel synthesis of diverse lariat lipopeptide libraries [3].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Enzymatic vs. Chemical Synthesis Approaches

| Synthetic Method | Number of Steps | Overall Yield | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chemical Synthesis | 19 steps | 33% | Full control over structure | Low efficiency, protecting groups required |

| Chemoenzymatic Approach | 17 steps (chemical) + 1 enzymatic | 83% (substrate) → quantitative cyclization | Minimal protecting groups, high yield | Requires enzyme production and optimization |

| One-Pot Tandem Strategy | Combined steps | Not specified | No intermediate purification, rapid diversification | Potential compatibility issues between steps |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NRPS Cyclase Studies

| Reagent/Enzyme | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PBP-type TEs (SurE, WolJ) | Macrocyclization catalysts | Broad substrate tolerance, strict l-nucleophile specificity, require minimal cofactors |

| Type I TE (TycC-TE) | Macrocyclization catalyst | α/β-hydrolase fold, processes diverse sequence and length variants |

| Ethylene Glycol (EG)-functionalized Resin | Solid support with simplified leaving group | Streamlines substrate synthesis, mimics natural pantetheine function |

| Dde Protecting Group | Orthogonal protection for lysine side chains | Selective removal with 2% hydrazine enables pseudo-N-terminus installation |

| Ser/Thr Ligation (STL) Reagents | Site-selective acylation | Compatible with one-pot procedures after enzymatic cyclization |

| H-Asp-OMe | H-Asp-OMe|Aspartic Acid Ester for Peptide Research | H-Asp-OMe is a protected aspartic acid derivative for RUO in peptide synthesis, notably for aspartame. Strictly for research; not for personal use. |

| 6-Isothiocyanato-Fluorescein | 6-Isothiocyanato-Fluorescein, CAS:3012-71-3, MF:C21H11NO5S, MW:389.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Analytical and Screening Approaches

Characterization Techniques

Comprehensive analysis of lariat lipopeptides requires multiple complementary techniques:

- Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS²): Essential for differentiating between head-to-tail and lariat cyclization products based on characteristic fragmentation patterns [1]

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Provide insights into substrate-enzyme interactions and the structural basis of regiospecificity [1]

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Confirms three-dimensional structure and macrocycle topology [6]

Biological Activity Screening

The therapeutic potential of synthesized lariat lipopeptides is evaluated through systematic biological screening:

Library Generation: The tandem cyclization-acylation approach enabled creation of a 51-member library of lariat lipopeptides with diverse sequences and acyl groups [1] [3]

Antimicrobial Profiling: Compounds are screened against clinically relevant pathogens including Mycobacterium intracellulare, Mycobacterium abscessus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli [3]

Potency Assessment: Eight compounds from the library inhibited M. intracellulare growth by 50% at concentrations of 8-16 µg mlâ»Â¹, demonstrating significant antimycobacterial activity [1] [3]

Figure 2: Integrated Workflow for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis and Screening of Lariat Lipopeptides

The emergence of non-ribosomal peptide cyclases as versatile biocatalytic tools represents a paradigm shift in complex peptide synthesis. The strategies outlined in this technical guide demonstrate how creative substrate engineering, combined with fundamental understanding of enzyme specificity, can overcome long-standing limitations in lariat lipopeptide production. The stereochemical control approach provides a elegant alternative to extensive protein engineering, leveraging nature's catalytic precision while expanding the accessible chemical space.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas:

- Enzyme Engineering: Directed evolution or rational design of NRPS cyclases with enhanced promiscuity, stability, and altered specificity [6]

- Expanded Substrate Scope: Incorporation of non-proteinogenic amino acids and chemically modified lipid chains to access unprecedented structural diversity [6]

- Process Optimization: Development of immobilized enzyme systems and continuous flow processes for scalable production [3]

- Therapeutic Translation: Advancement of promising lariat lipopeptide candidates through preclinical development toward clinical applications [1]

As the global threat of antimicrobial resistance intensifies, the ability to rapidly generate and optimize complex peptide architectures through these chemoenzymatic approaches will become increasingly valuable. The integration of enzymatic precision with synthetic flexibility represents a powerful strategy for accessing new therapeutic modalities to address unmet medical needs.

Substrate Engineering and Stereochemical Control for Modular Synthesis

The biosynthesis of complex lariat lipopeptides, a class of compounds with significant antimicrobial properties, has long been hampered by formidable synthetic challenges. Traditional approaches struggle with regioselective macrocyclization, often requiring extensive protecting group strategies and suffering from low yields under highly dilute conditions. This whitepaper details a groundbreaking chemoenzymatic strategy that repurposes versatile non-ribosomal peptide (NRP) cyclases to overcome these obstacles. The core innovation involves engineering branched peptide substrates featuring a 'pseudo-N-terminus'—an internal dipeptide unit installed on a lysine side chain. By manipulating the stereochemical configuration of potential nucleophiles, researchers have successfully redirected the cyclization specificity of powerful biocatalysts like the penicillin-binding protein-type thioesterase SurE. This paradigm shift enables the efficient, selective synthesis of lariat-shaped macrocycles, facilitating the construction of diverse libraries and the discovery of new anti-infective agents. The methodology represents a significant advance in the toolkit available to researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of synthetic biology and natural product biosynthesis.

Naturally occurring lariat lipopeptides are a structurally distinct and pharmaceutically vital class of natural products characterized by a carboxy-terminal macrocyclic "head" and a long, linear acyl "tail" [1]. Their complex architectures underpin diverse modes of biological action, particularly against bacterial pathogens. Clinically used exemplars include daptomycin, deployed against severe infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and drug-resistant enterococci, and colistin, a last-line defense against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens [1] [3]. The escalating global antibiotic resistance crisis necessitates the exploration of novel antibiotics, and the rich chemical space of lariat lipopeptides represents a promising frontier. However, the efficient synthesis and structural diversification of these molecules have been persistently hampered by their molecular complexity [1].

The primary synthetic obstacle lies in the regioselective construction of the macrocyclic ring [1]. Conventional chemical synthesis requires orthogonal protecting group strategies to differentiate between multiple nucleophilic sites (e.g., the native N-terminus, side-chain functional groups) and stoichiometric coupling reagents. Furthermore, to suppress undesired intermolecular oligomerization, these cyclizations must be performed under high dilution, consuming substantial volumes of organic solvents and limiting practical throughput [1]. In nature, these lariat-shaped scaffolds are typically assembled by non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), where a type-I thioesterase (TE) domain catalyzes the final cyclization step. Unfortunately, these native lariat-forming TEs generally exhibit narrow substrate specificity, showing sensitivity to changes in the position, stereochemistry, and nucleophilicity of the residue involved in ring closure [1]. This rigidity has severely restricted their utility as broad-spectrum biocatalysts for generating diverse lariat peptide libraries.

The Conceptual Framework: From Head-to-Tail to Lariat Cyclization

The Limitations of Existing NRP Cyclases

An emerging alternative to chemical synthesis involves harnessing NRPS cyclases as biocatalysts. Enzymes like the penicillin-binding protein-type TE SurE and the type-I TE TycC have gained attention for their exceptional promiscuity and efficiency in catalyzing the head-to-tail macrocyclization of linear peptide precursors [1] [3]. These versatile cyclases can tolerate a wide range of substrate sequences and lengths, operating under mild, aqueous conditions. However, their utility has been confined to a single topology: the canonical head-to-tail cyclic peptide, wherein the N-terminal amine attacks the C-terminal thioester [3]. Consequently, the formation of lariat topologies, which require a side-chain nucleophile to initiate cyclization, remained inaccessible to these otherwise powerful enzymes—until a fundamental rethinking of the substrate design.

The 'Pseudo-N-Terminus' Innovation

The core innovation detailed here is not the engineering of the enzyme, but the strategic redesign of its substrate. The research team hypothesized that the relaxed specificity of PBP-type TEs for the N-terminal nucleophile could be exploited by creating a substrate with more than one "N-terminus" [1] [3]. To this end, they engineered a branched peptide substrate containing an internal dipeptide unit attached via an isopeptide bond to the side chain of a lysine residue. This dipeptide unit presents a secondary amine group, termed the 'pseudo-N-terminus', which effectively competes with the native N-terminus as a potential nucleophile for the cyclization reaction [1].

Table: Key Components of the Branched Substrate Design

| Component | Description | Role in Cyclization |

|---|---|---|

| Native N-Terminus | The α-amine of the first amino acid in the peptide backbone. | A potential nucleophile for canonical head-to-tail cyclization. |

| Pseudo-N-Terminus | The α-amine of an internal dipeptide unit (e.g., l-Ile) attached to a Lys side chain. | A potential nucleophile for lariat (head-to-side-chain) cyclization. |

| C-Terminal EG Leaving Group | An ethylene glycol ester at the peptide C-terminus. | Mimics the natural pantetheine thioester, simplifying chemical synthesis [1]. |

| Stereochemical Control | Use of D-amino acids at the native N-terminus. | Blocks the head-to-tail pathway, forcing the enzyme to use the pseudo-N-terminus. |

The following diagram illustrates this conceptual shift from standard head-to-tail cyclization to the novel lariat-forming pathway, enabled by the pseudo-N-terminus.

Experimental Realization and Methodologies

Substrate Synthesis and Enzymatic Cyclization

The practical implementation of this strategy begins with the solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) of the branched, linear precursor. The peptide main chain is synthesized on a solid support functionalized with an ethylene glycol (EG) leaving group, which serves as a simplified mimic of the natural pantetheine moiety [1]. A critical step involves the orthogonal deprotection of a Dde-protected lysine side chain within the sequence. Following deprotection with 2% hydrazine, the pseudo-N-terminal dipeptide unit (e.g., l-Ile) is installed on the ε-amine of the lysine residue via a standard coupling reaction [1]. Subsequent resin cleavage and global deprotection yield the EG-functionalized branched peptide substrate, ready for enzymatic cyclization.

The branched substrate is incubated with a catalytic amount (e.g., 5 mol%) of the NRP cyclase, such as SurE, at 30°C. When the substrate possesses two L-configured N-termini (the native and the pseudo), the enzyme produces a mixture of both head-to-tail and lariat-shaped cyclic peptides in comparable amounts, demonstrating that the pseudo-N-terminus is as effective a nucleophile as the native one [1]. To achieve exclusive lariat formation, a stereochemical switch is employed. Since PBP-type TEs strictly accept only L-configured residues as nucleophiles, the native N-terminal residue is replaced with its D-configured analogue (e.g., D-Val). This substitution effectively blocks the head-to-tail cyclization pathway, forcing the enzyme to utilize the L-configured pseudo-N-terminus as the sole nucleophile, resulting in the quantitative and selective formation of the lariat macrocycle [1] [3].

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application in Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin-Binding Protein (PBP)-Type Thioesterases | A family of NRP cyclases (e.g., SurE, WolJ) with broad substrate tolerance. | Biocatalyst for regioselective macrocyclization of branched peptides [1]. |

| Type-I Thioesterase (TycC-TE) | An α/β-hydrolase fold enzyme from tyrocidine biosynthesis. | Alternative biocatalyst for head-to-tail and lariat cyclization [1]. |

| Ethylene Glycol (EG) Leaving Group | A diol-based C-terminal ester. | Surrogate for the pantetheine thioester, simplifying substrate synthesis [1]. |

| Orthogonal Protecting Group (Dde) | 1-(4,4-dimethyl-2,6-dioxocyclohex-1-ylidene)ethyl protecting group. | Protects the Lys side chain during SPPS, allowing for selective later functionalization [1]. |

| Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) | Automated or manual synthesis of peptides on a resin. | Foundation for constructing the complex branched peptide substrates [15]. |

Tandem Cyclization–Acylation for Lipopeptide Synthesis

A significant advantage of enzymatic transformations is their high selectivity, which often yields sufficiently pure products for subsequent reactions without intermediate purification. To complete the synthesis of lariat lipopeptides, the free N-terminus remaining after cyclization (the one not used in macrocyclization) was exploited as a reactive handle for further diversification [1] [3]. This was achieved through a tandem cyclization–acylation strategy using Ser/Thr ligation (STL), a site-selective acylation reaction.

Remarkably, both the enzymatic cyclization and the chemical acylation steps proceed sequentially in a one-pot reaction under mild conditions [1]. This streamlined process eliminates the need for laborious intermediate purification and enables efficient parallel synthesis. This modular approach was successfully deployed to generate a 51-member library of lariat lipopeptides equipped with various acyl groups, which could be directly screened for antimicrobial activity [1]. The entire workflow, from substrate design to functional lipopeptide, is summarized below.

Key Findings and Biological Relevance

The developed chemoenzymatic platform demonstrated remarkable efficiency and generality. The cyclization of the model branched substrate 4 by SurE proceeded quantitatively to yield the lariat peptide 5 [1]. This contrasts favorably with a purely chemical synthesis route, which provided the same lariat peptide in a yield of only 33% over 19 steps; the chemoenzymatic route, by comparison, achieved an 83% yield for the linear precursor over 17 steps, followed by quantitative cyclization [1]. The strategy was also shown to be generalizable across different enzyme families, as demonstrated by the successful repurposing of WolJ (another PBP-type TE) and TycC-TE for lariat peptide synthesis [1].

The power of this methodology for drug discovery was validated through biological screening. The 51-member library of lariat lipopeptides generated via the tandem cyclization–acylation approach was screened against a panel of pathogens, including Mycobacterium intracellulare, Mycobacterium abscessus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli [1]. The screening revealed that the site-selective acylation was crucial for conferring antimycobacterial activity, leading to the identification of several hit compounds. Notably, eight lipopeptides were found to inhibit the growth of M. intracellulare by 50% at concentrations of 8–16 µg mlâ»Â¹, underscoring the therapeutic potential of this synthetic platform [1].

Table: Quantitative Outcomes of the Chemoenzymatic Approach

| Parameter | Result / Value | Context / Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Lariat Cyclization Yield | Quantitative (for substrate 4 with SurE) | Demonstrates high efficiency and conversion of the enzymatic step [1]. |

| Chemical Synthesis Yield | 33% (over 19 steps) | Highlights the synthetic challenge of traditional methods [1]. |

| Chemoenzymatic Yield | 83% (linear precursor) + ~100% (cyclization) | Showcases the superior efficiency of the hybrid approach [1]. |

| Library Size | 51 members | Demonstrates the utility for generating structural diversity [1]. |

| Best MICâ‚…â‚€ Values | 8–16 µg mlâ»Â¹ (against M. intracellulare) | Confirms the biological relevance and identifies promising anti-infective hits [1]. |

The innovation of designing branched peptides with a 'pseudo-N-terminus' represents a paradigm shift in the biosynthesis of complex lariat lipopeptides. By moving beyond traditional enzyme engineering and focusing instead on strategic substrate design, this research has successfully repurposed highly versatile NRP cyclases for a new catalytic function. The incorporation of a stereochemical switch ensures exclusive regiospecificity, enabling the efficient and modular construction of lariat macrocycles that were previously inaccessible via these biocatalysts. When integrated with a one-pot acylation step, this platform provides a powerful route for generating structurally diverse lipopeptide libraries directly amenable to biological screening. This approach not only streamlines the synthesis of an important class of antimicrobial agents but also opens new avenues for exploring the chemical space of macrocyclic peptides for various therapeutic applications. For researchers in synthetic biology and drug discovery, this methodology offers a robust, efficient, and generalizable tool for accessing complex natural product-like scaffolds.

Harnessing Enzyme Stereospecificity as a Cyclization Switch

The biosynthesis of complex natural products, such as lariat lipopeptides, represents a significant area of research in drug discovery and development. These compounds, characterized by their macrocyclic "head" and linear lipid "tail," include important antibiotics like daptomycin and colistin [1] [3]. However, their structural complexity, particularly the regioselective construction of the macrocyclic ring, poses substantial synthetic challenges that have hampered efficient structural diversification and the development of new therapeutic agents [1]. Traditional chemical synthesis of these lariat-shaped lipopeptides requires orthogonal protecting group strategies and stoichiometric coupling reagents, often necessitating dilute conditions to suppress intermolecular coupling, which involves substantial amounts of organic solvents [1].

An emerging alternative methodology leverages the power of enzymatic catalysis, specifically non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) and their associated cyclization domains, which catalyze peptide cyclization regio-, chemo-, and stereoselectively under mild conditions [1] [16]. This technical guide explores the paradigm of harnessing enzyme stereospecificity as a molecular switch to control cyclization outcomes, with a specific focus on the biosynthesis of lariat lipopeptides by non-ribosomal peptide cyclases. The precise manipulation of this stereochemical switching mechanism offers a powerful strategy for the efficient synthesis and diversification of complex macrocyclic peptides, opening new avenues for drug discovery.

Conceptual Framework: Stereospecificity as a Cyclization Control Element

Fundamentals of Enzyme Stereospecificity

Enzyme stereospecificity refers to the ability of enzymes to discriminate between chiral substrates, enantiomers, or stereoisomers [17]. This exquisite selectivity stems from the inherently chiral nature of enzymes themselves, which are composed of L-amino acids (with the exception of glycine) and thus form asymmetric three-dimensional active sites [17]. In the context of non-ribosomal peptide synthesis, this stereospecificity plays a crucial role in determining substrate selection, catalytic activity, and ultimately, product structure.

The biosynthetic machinery for non-ribosomal peptide synthesis utilizes large multienzyme complexes that operate as assembly lines, catalyzing stepwise peptide condensation without direct ribosomal involvement [18]. These systems incorporate a diverse array of building blocks, including D-amino acids, N-methylated residues, and heterocyclic elements, providing structural features not commonly found in ribosomally synthesized peptides [18]. The final cyclization step, essential for constraining peptide conformation and often for biological activity, is typically catalyzed by specialized domains such as thioesterase (TE) domains or condensation-like (CT) domains [16] [18].

Lariat Lipopeptide Biosynthesis: The Cyclization Challenge

Lariat lipopeptides represent a topologically distinct class of macrocyclic peptides characterized by a carboxy-terminal macrocyclic head group and a long acyl chain appended to the amino-terminal tail [1]. Naturally occurring lariat lipopeptides are typically biosynthesized via non-ribosomal pathways in which lariat-shaped macrocyclic scaffolds are constructed by type-I thioesterases (TEs), an α/β-hydrolase fold enzyme fused to the C terminus of a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase [1]. These lariat-forming TEs catalyze selective cyclization using side chain nucleophiles, but they generally demonstrate narrow substrate specificity and sensitivity to changes in the local environment of the nucleophilic residue, including its position, stereochemistry, and nucleophilicity [1]. This sensitivity has limited their application in generating structurally diverse lariat peptides.

Table 1: Key Enzymes in Peptide Cyclization

| Enzyme Type | Structural Features | Native Function | Substrate Flexibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type-I Thioesterases (TEs) | α/β-Hydrolase fold fused to NRPS C-terminus | Lariat formation using side chain nucleophiles | Low sensitivity to changes in nucleophile position and stereochemistry |

| PBP-Type Thioesterases (e.g., SurE, WolJ) | Penicillin-binding protein fold | Head-to-tail macrocyclization | High tolerates diverse sequences and lengths |

| Fungal CT Domains | Condensation-like domain terminating NRPS | Macrocyclization in fungal systems | Varies between specific systems |

Experimental Implementation of Stereospecificity Switching

Redesigning Substrate Architecture

A groundbreaking approach to controlling cyclization outcomes involves engineering the shape of substrates rather than the enzymes themselves. This strategy was successfully demonstrated in recent work by Kobayashi and colleagues, who repurposed the head-to-tail cyclase SurE for lariat peptide synthesis through strategic substrate redesign [1] [3]. SurE, a penicillin-binding protein-type thioesterase, normally exhibits strict specificity for a D-configured C-terminal α-amino acid and an L-configured N-terminal α-amino acid, resulting in canonical head-to-tail cyclic peptides [1].

To redirect this specificity toward lariat formation, researchers introduced an internal dipeptide unit functioning as a "pseudo-N terminus," where L-Ile was attached to the side chain of L-Lys via an isopeptide bond [1]. The resulting branched substrate contained two N-terminal L-amino acids, both capable of serving as nucleophiles for cyclization. When this engineered substrate was incubated with SurE, the enzyme produced both the expected head-to-tail cyclic peptide (60%) and a novel lariat-shaped cyclic peptide (40%), where the pseudo-N-terminal L-Ile in the dipeptidyl unit acted as the nucleophile for cyclization [1]. This demonstrated that the pseudo-N terminus could compete effectively with the native N terminus as a nucleophile in SurE-catalyzed cyclization.

Stereochemical Control of Regiospecificity

To achieve exclusive lariat formation, researchers exploited the stereospecificity of PBP-type TEs, which strictly recognize the stereochemical configuration of the nucleophile, accepting only L-configured residues while rejecting D-configured residues [1] [3]. By replacing the native N-terminal L-Ile residue with D-Val, the head-to-tail cyclization pathway was effectively suppressed, forcing the enzyme to utilize the pseudo-N-terminal L-Ile as the exclusive nucleophile [1].

This stereochemical switching approach resulted in quantitative production of the lariat-shaped cyclic peptide, with complete regiospecificity for the pseudo-N-terminal nucleophile [1]. Notably, even though the substrate contained three different potential nucleophiles (N-terminal D-Val, pseudo-N-terminal L-Ile, and the ε-NH₂ of L-Lys), cyclization occurred exclusively via the pseudo-N-terminal L-Ile, demonstrating the powerful gatekeeping function of enzyme stereospecificity.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of Stereochemical Switching in SurE-Catalyzed Cyclization

| Substrate Structure | N-terminal Residue | Pseudo-N-terminal Residue | Major Product | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear peptide with native N-terminus | L-Ile | Not present | Head-to-tail cyclic peptide | N/A |

| Branched peptide with dual L-nucleophiles | L-Ile | L-Ile | Mixed: 60% head-to-tail, 40% lariat | 100% conversion |

| Branched peptide with stereochemical switch | D-Val | L-Ile | Exclusive lariat peptide | Quantitative |

Molecular Basis of Stereospecificity

Molecular dynamics simulations provided insights into the structural basis for the observed stereospecificity [1]. Using the crystal structure of apo SurE, researchers constructed covalent docking models with substrates containing different stereochemical configurations. These simulations revealed that when an L-configured nucleophile (L-Ile) was positioned in the nucleophile binding site, it remained stably bound during 50 ns of molecular dynamics simulations, with the distance between the nucleophilic amine and the C-terminal carbonyl carbon averaging 4.5 Å – conducive to catalysis [1].

In contrast, when the configuration of the N-terminal residue was inverted to D-allo-Ile, significant variability in the position of the N terminus was observed, with the distance between the nucleophilic amine and the electrophilic carbon exceeding 10 Ã…, rendering catalysis unfavorable [1]. These computational findings align with the experimental observations and suggest that the nucleophile stereoselectivity stems from the spatial arrangement of the side chain-recognizing pocket and a proton-abstracting tyrosine residue (Tyr154) in the nucleophile binding site of SurE.

Diagram 1: Mechanism of stereochemical switching in SurE-catalyzed cyclization. The native pathway (top) utilizes the L-configured N-terminus as a nucleophile for head-to-tail cyclization. The switched pathway (bottom) employs a D-configured N-terminus to block the native pathway, forcing the enzyme to use the L-configured pseudo-N-terminus for lariat formation.

Research Protocols and Methodologies

Substrate Design and Synthesis Protocol

The successful implementation of stereospecificity switching requires precise substrate design and synthesis. The following protocol outlines the key steps for preparing branched peptide substrates with controlled stereochemistry:

Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS): Synthesize the linear peptide backbone on a solid support functionalized with an ethylene glycol (EG) leaving group at the C-terminus [1]. The EG group serves as a surrogate for the pantetheine leaving group, simplifying substrate synthesis and streamlining the enzymatic process.

Orthogonal Protection Strategy: Incorporate an L-Lys residue with its side chain protected by a 1-(4,4-dimethyl-2,6-dioxocyclohex-1-ylidene)ethyl (Dde) group, which can be selectively removed without affecting other protecting groups [1].

Side Chain Deprotection: Remove the Dde protecting group using 2% hydrazine solution, exposing the ε-amino group of the L-Lys residue [1].

Pseudo-N-Terminus Installation: Couple L-Ile or another L-configured amino acid to the exposed ε-amino group of L-Lys using standard peptide coupling reagents, creating the branched dipeptidyl unit with a pseudo-N-terminus [1].

Global Deprotection and Cleavage: Cleave the peptide from the resin and remove all protecting groups simultaneously, yielding the ethylene glycol-functionalized branched peptide substrate ready for enzymatic cyclization [1].