Overcoming Product Inhibition in Biosynthesis: Advanced Strategies for Enhanced Metabolic Yield and Therapeutic Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of product inhibition, a fundamental regulatory mechanism in enzymatic biosynthesis where the end product negatively feedback-inhibits its own synthesis, limiting metabolic yield.

Overcoming Product Inhibition in Biosynthesis: Advanced Strategies for Enhanced Metabolic Yield and Therapeutic Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of product inhibition, a fundamental regulatory mechanism in enzymatic biosynthesis where the end product negatively feedback-inhibits its own synthesis, limiting metabolic yield. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of allosteric and feedback inhibition across pathways like amino acid and siderophore biosynthesis. The scope extends to methodological advances in screening and characterization, practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing industrial and therapeutic processes, and finally, to rigorous validation and comparative analysis of these approaches. The synthesis of this information aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to overcome this bottleneck, thereby accelerating innovations in biotechnology and drug development.

Understanding Product Inhibition: The Natural Brakes on Metabolic Pathways

Defining Allosteric Feedback Inhibition and its Physiological Role

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is allosteric feedback inhibition? Allosteric feedback inhibition is a fundamental regulatory mechanism where the end-product of a metabolic pathway binds to an allosteric site on an enzyme (typically the first committed-step enzyme), causing a conformational change that reduces the enzyme's activity. This binding occurs at a location distinct from the enzyme's active site and acts as a rapid, negative feedback loop to prevent overproduction of the pathway's end-product [1] [2].

2. How does it differ from other types of enzyme inhibition? Unlike competitive inhibition, where an inhibitor competes with the substrate for the active site, allosteric feedback inhibitors bind to a separate, regulatory site. This often results in non-competitive or uncompetitive inhibition patterns, where the inhibitor can bind to both the enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex, reducing the maximum reaction rate (Vmax) and potentially altering the enzyme's affinity for its substrate (Km) [2] [3].

3. What is its primary physiological role? The primary role is to maintain metabolic homeostasis and ensure efficient use of cellular energy and resources. It allows a cell to dynamically control the flux through biosynthetic pathways, preventing the wasteful over-accumulation of metabolites. This provides a crucial layer of regulation that is independent of transcription and translation, allowing for nearly instantaneous response to metabolic demands [1] [4] [3].

4. Why is understanding this mechanism important for biosynthesis research? In industrial biotechnology, the natural feedback inhibition of biosynthetic pathways strongly limits the overproduction of desired compounds, such as amino acids. Overcoming this inhibition is a key objective in metabolic engineering. By understanding the structural basis of allostery, researchers can design "desensitized" enzyme variants that are resistant to feedback inhibition, thereby enabling the construction of efficient microbial cell factories for high-yield production [5] [6].

Key Quantitative Data in Allosteric Feedback Inhibition

The tables below summarize empirical data from studies on allosteric feedback inhibition, highlighting the metabolic consequences of its disruption and specific kinetic parameters of inhibited enzymes.

Table 1: Metabolic Impact of Removing Allosteric Feedback Inhibition in E. coli Amino Acid Pathways

| Dysregulated Pathway | End Product Accumulation | Change in Enzyme Levels | Flux Limitation? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arginine | Increased 2-16 fold | Decreased | No |

| Tryptophan | Increased 2-16 fold | Decreased | No |

| Histidine | Increased 2-16 fold | Decreased | No |

| Threonine | Increased 2-16 fold | Decreased | No |

| Leucine | Increased 2-16 fold | Decreased | No |

| Proline | Increased 2-16 fold | No Change | No |

| Isoleucine | Increased 2-16 fold | No Change | No |

Source: Sander et al. (2019) [4]. Data demonstrates that removing feedback inhibition leads to metabolite accumulation and compensatory downregulation of enzyme expression, while revealing inherent enzyme overabundance that maintains flux.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Inhibition Constants for Allosteric Enzymes

| Enzyme | Organism | Inhibitor (End Product) | Reported Kᵢᵢ (Inhibition Constant) | Inhibition Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP-Phosphoribosyltransferase (HisG) | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | L-Histidine | 4 µM (at neutral pH) | Uncompetitive vs ATP; Noncompetitive vs PRPP |

| Homoserine Dehydrogenase | Corynebacterium glutamicum | L-Threonine | Not Specified (>90% activity lost with 10 mM) | Allosteric Feedback |

| Homoserine Dehydrogenase | Corynebacterium glutamicum | L-Isoleucine | Not Specified (>90% activity lost with 25 mM) | Allosteric Feedback |

Source: Mechanism of Feedback Allosteric Inhibition of ATP Phosphoribosyltransferase (2012) and Engineering allosteric inhibition of homoserine dehydrogenase (2024) [3] [5]. Kᵢᵢ represents the concentration of inhibitor required to achieve half-maximal inhibition.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inability to relieve feedback inhibition in a production strain. Solution: Employ a semi-rational engineering approach combining structural analysis and high-throughput screening.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Determine Oligomeric State: Confirm the native oligomeric state (e.g., dimer, tetramer, hexamer) of your target enzyme using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) or analytical ultracentrifugation. Allosteric regulation is often linked to quaternary structure [3] [5].

- Identify Mutation Sites: Use homology modeling and multiple sequence alignment to identify conserved amino acid residues at the subunit interface or within the predicted effector-binding domain [5] [6].

- Build Mutant Library: Perform saturation mutagenesis on the selected target residues.

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Develop a growth-based screening method. For example, plate the mutant library on solid media containing a toxic analog of the pathway's end-product (e.g., a threonine analog for homoserine dehydrogenase mutants). Resistant colonies are likely to harbor feedback-relieved mutants [5].

- Validate and Characterize: Purify the wild-type and mutant enzymes. Perform enzyme activity assays in the presence and absence of the inhibitor to quantitatively confirm the relief of feedback inhibition while retaining high catalytic activity [5].

Problem: Determining the kinetic mode of inhibition is inconclusive. Solution: Perform a comprehensive steady-state kinetic analysis.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Measure Initial Velocities: Conduct a series of enzyme assays where the substrate concentration is varied across a range, with each series performed at a different, fixed concentration of the allosteric inhibitor.

- Plot and Analyze Data: Plot the data using Lineweaver-Burk (double-reciprocal) plots or fit the data directly to the Michaelis-Menten equation using non-linear regression.

- Diagnose the Pattern:

- If the lines on a Lineweaver-Burk plot intersect on the y-axis, inhibition is competitive.

- If the lines are parallel, inhibition is uncompetitive.

- If the lines intersect to the left of the y-axis, and the intersection point's x-coordinate is not equal to -1/Km, inhibition is mixed-type.

- If the lines intersect to the left of the y-axis on the x-axis (x-coordinate = -1/Km), inhibition is non-competitive [2] [3].

- For allosteric inhibitors, non-competitive or mixed-type inhibition is commonly observed, as the inhibitor binds to a site distinct from the active site, affecting catalysis (Vmax) and potentially substrate binding (Km) [2].

Essential Pathways and Workflows

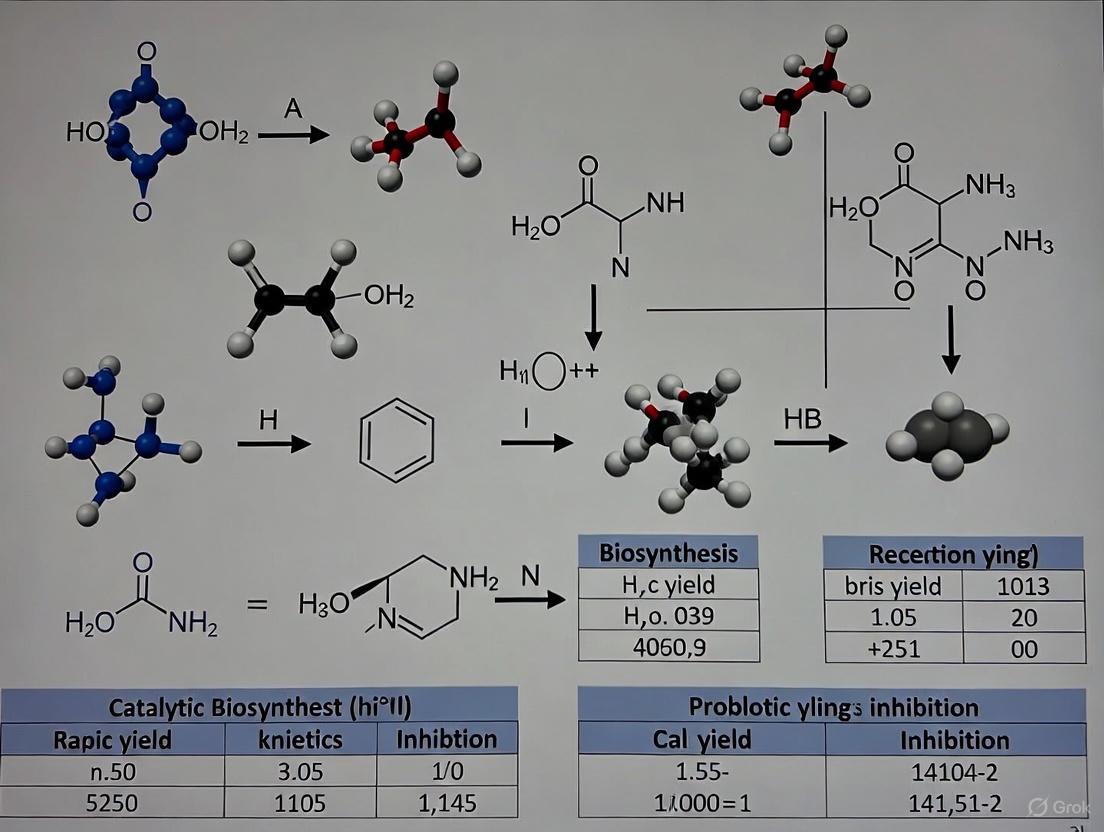

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and regulatory feedback within a classic biosynthetic pathway governed by allosteric feedback inhibition.

Classic Feedback Inhibition Loop

The experimental workflow for engineering enzymes with relieved feedback inhibition is outlined below.

Enzyme Deregulation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Studying Allosteric Feedback Inhibition

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Allosteric Enzyme Mutants (e.g., ArgA, HisG) | Study the metabolic and kinetic consequences of removed feedback regulation. | Scarless CRISPR or site-directed mutagenesis is used to introduce point mutations that abolish inhibitor binding while preserving catalytic activity [4]. |

| Amino Acid Analogs (e.g., Threonine analog) | High-throughput screening for feedback-resistant mutants. | Toxic analogs mimic the natural end-product, allowing only mutants with relieved inhibition to grow on selective media [5]. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Quantitative metabolomics to measure intracellular metabolite concentrations. | Used to confirm elevated end-product levels (e.g., 2-16 fold increases) in feedback-dysregulated strains [4]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Determine the native oligomeric state of an allosteric enzyme. | Critical as allosteric regulation often involves conformational changes across multiple subunits (e.g., dimer to hexamer) [3] [5]. |

| GFP-Promoter Fusions | Monitor changes in enzyme expression levels in live cells. | Reports on transcriptional-level compensatory mechanisms in response to pathway dysregulation [4]. |

| Vallesamine N-oxide | Vallesamine N-oxide, CAS:126594-73-8, MF:C20H24N2O4, MW:356.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Indoleacetonitrile | 3-Indoleacetonitrile, CAS:771-51-7, MF:C10H8N2, MW:156.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The aspartate-family biosynthesis pathway is a crucial metabolic route in plants and microorganisms, leading to the production of four essential amino acids: lysine (Lys), threonine (Thr), methionine (Met), and isoleucine (Ile) [7]. From a nutritional and biotechnological standpoint, this pathway is a primary target for metabolic engineering, as these amino acids must be supplemented in the diets of humans and monogastric livestock [7]. A significant challenge in optimizing the yield of these amino acids, particularly through engineered biological or catalytic systems, is product inhibition. This phenomenon occurs when the end products of a reaction act as potent inhibitors of the enzymes responsible for their own synthesis, severely limiting the efficiency and throughput of the production process [8] [9]. This technical support center provides a focused guide on identifying, troubleshooting, and overcoming product inhibition in aspartate-family amino acid biosynthesis.

FAQs on Product Inhibition in Biosynthesis

Q1: What is product inhibition and why is it a major problem in catalytic biosynthesis? Product inhibition is a form of enzyme regulation where the product of a catalytic reaction binds to the enzyme and suppresses its activity, preventing catalytic turnover [8] [10]. In the context of biosynthesis, this leads to incomplete conversions and low yields. For example, in the aspartate pathway, the accumulation of Lys can inhibit key enzymes in its own biosynthetic pathway, creating a negative feedback loop that halts production long before the substrate is fully consumed [7].

Q2: How can I experimentally determine if my biosynthesis experiment is suffering from product inhibition? A straightforward experimental test involves running the reaction with and without the suspected inhibiting product included in the initial feed mixture [8]. If the initial reaction rate is significantly lower when the product is pre-added, product inhibition is likely occurring. For instance, in NO oxidation over catalysts, including the product NO2 in the feed stream was necessary to obtain accurate, uninhibited kinetic parameters [8].

Q3: What are the consequences of ignoring product inhibition in kinetic studies? Failure to account for product inhibition during kinetic analysis can lead to significant errors in calculated parameters [8]. This includes:

- Lower apparent activation energy: As temperature increases, conversion and product concentration rise, which diminishes the observed rate increase.

- Lower apparent reaction order: Increasing reactant concentration produces more product, which dampens the expected rate response [8]. These inaccuracies can misguide the rational design of improved catalytic or enzymatic systems.

Q4: What general strategies exist for overcoming product inhibition? Several biochemical and chemical engineering strategies can be employed:

- In situ product removal (ISPR): Using adsorbents or extraction methods to physically remove the inhibitory product from the reaction environment as it is formed [9].

- Enzyme engineering: Developing enzyme variants through directed evolution or rational design that have lower affinity for the inhibitory product while maintaining high catalytic activity.

- Co-feeding: Introducing the inhibitory product at the start of the experiment to saturate potential inhibition sites and maintain a consistent, quantifiable level of inhibition throughout the kinetic study [8].

- Process engineering: Utilizing specific reactor configurations (e.g., membrane reactors) that allow for continuous separation of products from the catalyst.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Incomplete Conversion Despite Excess Substrate

- Description: The reaction stalls at a conversion plateau well below 100%, even though plenty of starting material remains.

- Possible Cause: Strong inhibition by one or more reaction products.

- Solution:

- Confirm the Cause: Spike the reaction mixture with purified product. A further decrease in rate confirms inhibition.

- Employ ISPR: Add a polymeric adsorbent to the reaction. For example, MP-carbonate has been successfully used to scavenge inhibitory phenol co-products in ene-reductase catalyzed disproportionations, pushing conversions from ≤65% to >90% [9].

- Consider Metabolic Engineering: In biological systems, consider knockout mutations of genes encoding catabolic enzymes. In one study, combining a feedback-insensitive enzyme with a knockout of lysine catabolism successfully increased free Lys levels in seeds [7].

Problem: Retarded Microbial Growth or Seed Germination in Production Strains

- Description: Engineered microbial strains or plants show poor growth or delayed germination, despite high product titers.

- Possible Cause: Disruption of central metabolism due to pathway engineering. Enhancing the flux towards one product (e.g., Lys) can starve the TCA cycle of intermediates (like oxaloacetate and pyruvate), reducing energy production [7].

- Solution:

- Analyze Metabolites: Use GC-MS to profile central metabolites. A reduction in TCA cycle intermediates like fumarate and citrate confirms competition for precursors [7].

- Use Inducible Promoters: Implement seed-specific or inducible promoters to decouple product synthesis from growth phases, minimizing interference with cellular energy status [7].

Problem: Inaccurate Measurement of Kinetic Parameters

- Description: Experimentally determined activation energies and reaction orders are unexpectedly low and non-integer.

- Possible Cause: Unaccounted product inhibition during initial-rate measurements, even at low conversions [8].

- Solution:

- Co-feed Products: Conduct kinetic experiments with the inhibiting product present at a fixed, known concentration in the initial feed stream [8].

- Use a Differential Reactor: Ensure the reactor is operated at a sufficiently low conversion where product concentration is negligible, though this may not always be practically feasible [8].

Quantitative Data on Product Inhibition

Table 1: Consequences of Unaccounted Product Inhibition on Kinetic Parameters

| Kinetic Parameter | Apparent Value (with Inhibition) | True Value (without Inhibition) | Primary Cause of Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Energy (Ea) | Lower | Higher | Increased temperature raises product concentration, which diminishes the observed rate increase [8]. |

| Reaction Order (w.r.t. reactant) | Lower | Higher | Increased reactant concentration yields more inhibitory product, dampening the rate response [8]. |

Table 2: Strategies to Overcome Inhibition in Aspartate-Derived Amino Acid Production

| Strategy | Experimental Example | Key Outcome | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Situ Product Removal | Use of MP-carbonate to adsorb phenol during alkene reduction [9]. | Conversion increased from ≤65% to >90%. | Scavenger must be specific and not remove substrate or catalyst. |

| Metabolic Engineering | Seed-specific expression of feedback-insensitive DHDPS and knockout of LKR/SDH in Arabidopsis [7]. | Significant increase in free Lys level in seeds. | Can cause metabolic imbalance and retard germination [7]. |

| Enzyme Engineering | Use of a feedback-insensitive dihydrodipicolinate synthase (DHDPS) in Lys synthesis [7]. | Increased flux into the Lys branch of the pathway. | Requires deep understanding of enzyme structure and allosteric sites. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Testing for Product Inhibition via Co-feeding

Objective: To determine if a specific product is inhibiting a biosynthesis reaction. Materials: Purified substrate, purified putative inhibitory product, catalyst (enzyme or whole cells), buffer, standard lab equipment (reactor, HPLC/GC for analysis). Procedure:

- Prepare two identical reaction mixtures containing the substrate and catalyst.

- To the experimental mixture, add a known concentration of the purified product. The control mixture has no added product.

- Initiate the reactions simultaneously under the same conditions (temperature, agitation).

- Monitor the initial rate of substrate consumption or product formation in both mixtures.

- Interpretation: If the initial rate in the experimental mixture (with added product) is significantly lower than in the control, the product is an inhibitor of the reaction [8].

Protocol 2: In Situ Product Removal Using a Scavenging Resin

Objective: To increase reaction conversion by continuously removing an inhibitory co-product. Materials: Substrate, catalyst, inhibitory product scavenger (e.g., MP-carbonate), appropriate buffer, anaerobic vial (if required), shaker [9]. Procedure:

- Set up the reaction in a vial according to your standard protocol (e.g., substrate in degassed buffer).

- Add a measured amount of the scavenging resin (e.g., 40 equivalents of loading capacity relative to the theoretical phenol produced) [9].

- Initiate the reaction by adding the catalyst.

- Agitate the mixture to allow the scavenger to adsorb the inhibitory product as it forms.

- Optimization Note: The amount of scavenger may need optimization. Run control reactions without scavenger to directly compare final conversion.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram Title: Aspartate Biosynthesis Pathway and Key Inhibition Points

Diagram Title: Troubleshooting Workflow for Suspected Product Inhibition

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying the Aspartate Family Pathway

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback-Insensitive DHDPS | A key bacterial enzyme in lysine synthesis that is not subject to feedback inhibition by Lys. | Used in metabolic engineering to push carbon flux toward Lys overproduction [7]. |

| MP-Carbonate | A polymeric adsorbent that acts as a scavenger for phenolic compounds. | In situ removal of inhibitory phenol co-products in OYE-family enzyme reactions [9]. |

| LKR/SDH Knockout Mutant | A genetic line lacking the bifunctional lysine-ketoglutarate reductase/saccharopine dehydrogenase enzyme. | Used to block the catabolism of Lys, leading to its accumulation in seeds [7]. |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase | Catalyzes the transamination of oxaloacetate to aspartate. | The foundational enzyme for initiating the entire aspartate-family biosynthetic pathway [11]. |

| Perlolyrin | Perlolyrin, CAS:29700-20-7, MF:C16H12N2O2, MW:264.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Peiminine | Peiminine, MF:C27H43NO3, MW:429.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My enzyme's reaction rate has dropped significantly, but adding more substrate doesn't help. What type of inhibition should I suspect? This behavior is characteristic of non-competitive inhibition [12] [13]. In this mechanism, the inhibitor binds to an allosteric site on the enzyme, reducing the catalytic rate (Vmax) regardless of how much substrate is present [14]. Since the inhibitor does not block the active site, increasing substrate concentration cannot overcome the inhibition. To confirm, perform kinetic assays; a unchanged Km with a decreased Vmax indicates non-competitive inhibition [15] [16].

Q2: How can I experimentally distinguish between competitive and uncompetitive inhibition? The key is to analyze how the inhibitor affects the enzyme's kinetic parameters, Km and Vmax, using Michaelis-Menten or Lineweaver-Burk plots [16].

- Competitive Inhibition: The apparent Km increases, while Vmax remains unchanged [15] [13]. The inhibitor competes with the substrate for the active site.

- Uncompetitive Inhibition: Both the apparent Km and Vmax decrease [16] [17]. The inhibitor binds only to the Enzyme-Substrate complex.

Q3: What is "product inhibition" and why is it a problem in catalytic biosynthesis? Product inhibition occurs when the final product of a catalytic pathway acts as an inhibitor of an enzyme earlier in the same pathway [18]. This is a common form of feedback regulation in metabolism. In biosynthesis, this can severely limit reaction yield and efficiency, as the accumulating product shuts down its own production [19]. Overcoming this, such as by using specific solvents or low catalyst loadings, is a key goal in industrial biocatalysis [19].

Q4: Are there any clinical applications for these inhibition types? Yes, understanding these mechanisms is fundamental to pharmacology.

- Competitive Inhibitors include drugs like Methotrexate (for cancer and rheumatoid arthritis) and Sildenafil [15] [13].

- Non-Competitive Inhibitors are seen in cases of cyanide poisoning, where cyanide inhibits cytochrome c oxidase, and in the action of some heavy metals like lead and mercury [14] [12].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low reaction rate that does not improve with more substrate. | Non-competitive inhibition [14]. | Identify and remove the allosteric inhibitor. Increase enzyme concentration, as the inhibitor inactivates enzyme molecules [13]. |

| Low reaction rate that improves with high substrate concentration. | Competitive inhibition [15]. | Increase substrate concentration to outcompete the inhibitor. Purify the substrate to remove inhibitory contaminants. |

| Unexpected changes in Km and Vmax that don't fit standard models. | Mixed inhibition or allosteric regulation [16] [20]. | Perform more detailed kinetic analysis to determine inhibitor binding constants for the free enzyme and enzyme-substrate complex. |

| Enzyme activity decreases over time during the reaction. | Product inhibition [19] [18]. | Implement a continuous process to remove the inhibitory product, or engineer the enzyme to reduce its affinity for the product. |

| Inhibition potency changes with substrate concentration. | Uncompetitive inhibition (potency increases) [16] or Competitive inhibition (potency decreases) [15]. | Carefully model substrate and inhibitor dependence to identify the correct mechanism. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Determining Mechanism of Action via Steady-State Kinetics

Objective: To characterize the type of reversible inhibition for a novel compound.

Materials:

- Purified target enzyme

- Substrate(s)

- Inhibitor compound

- Assay buffer

- Spectrophotometer or other detection instrument

Method:

- Initial Rate Measurements: Perform a series of enzyme reactions with varying substrate concentrations (e.g., 0.5x, 1x, 2x, and 5x Km) both in the absence and presence of at least two different, fixed concentrations of the inhibitor [16].

- Data Analysis: Plot the initial velocity (v) against substrate concentration ([S]) for each condition.

- Linear Transformation: Create a Lineweaver-Burk (double-reciprocal) plot (1/v vs. 1/[S]) for all datasets [14].

- Interpretation: Analyze the patterns in the Lineweaver-Burk plot:

The following table summarizes the kinetic parameter changes for the primary types of reversible inhibition.

Table 1: Kinetic Signatures of Reversible Enzyme Inhibition

| Inhibition Type | Binding Site | Apparent Km (Affinity) | Apparent Vmax (Rate) | Overcoming by ↑ [S]? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | Active Site | Increases [15] [12] [13] | Unchanged [15] [12] [13] | Yes [15] [17] |

| Non-Competitive | Allosteric Site | Unchanged [14] [12] [13] | Decreases [14] [12] [13] | No [14] [17] |

| Uncompetitive | Allosteric Site (on ES complex) | Decreases [16] [17] | Decreases [16] [17] | No [20] |

Visualization of Mechanisms & Workflows

Mechanisms of Enzyme Inhibition

Mechanism of Action Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Inhibition Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate | A classic competitive inhibitor of Dihydrofolate Reductase (DHFR). Used as a positive control in competitive inhibition assays [15]. | Resembles the natural substrate, folate. Useful for studying nucleotide metabolism inhibition. |

| Malonate | A classic competitive inhibitor of Succinate Dehydrogenase. Used to study metabolic pathway regulation [13] [17]. | Structurally similar to succinate, making it an excellent teaching and model system inhibitor. |

| Heavy Metal Ions (e.g., Pb²âº, Hg²âº) | Act as non-competitive inhibitors for many enzymes. Used to study allosteric and toxicological inhibition mechanisms [14] [17]. | Can cause irreversible denaturation over time. Use carefully at defined concentrations. |

| Hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) | A strong hydrogen-bond-donating solvent. Used in catalysis to help overcome product inhibition, enabling lower catalyst loadings [19]. | Changes the solvent environment, which can alter enzyme kinetics and stability. |

| Cyanide Salts | A potent non-competitive inhibitor of Cytochrome c Oxidase. Used to study mitochondrial electron transport chain disruption [14] [12]. | EXTREMELY TOXIC. Use only with strict safety protocols in a controlled environment. |

| Lineweaver-Burk Plot | A graphical tool for analyzing enzyme kinetics data. Used to visually diagnose the type of inhibition based on the pattern of lines [14]. | Can be prone to error amplification at low substrate concentrations. Always pair with Michaelis-Menten plots. |

| Etioporphyrin I | Etioporphyrin I, CAS:448-71-5, MF:C32H38N4, MW:478.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Acalyphin | Acalyphin, CAS:81861-72-5, MF:C14H20N2O9, MW:360.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Understanding Product Inhibition

What is product inhibition and why is it a critical issue in biocatalysis?

Product inhibition is a form of enzyme regulation where the final product of a reaction binds to the enzyme, reducing its activity and slowing down further production [21] [22]. This acts as a natural negative feedback mechanism in cells [23]. In industrial biotechnology, this is a major bottleneck because it limits the yield and productivity of desired compounds, such as biofuels, antibiotics, and organic acids [21] [22] [24]. Overcoming it is essential for economically viable bioprocesses.

How does competitive product inhibition differ from other types of inhibition?

In competitive product inhibition, the product molecule, which often structurally resembles the substrate, binds to the same active site on the enzyme [21] [15]. This prevents the substrate from binding. The key kinetic signature is that the apparent Michaelis constant (Kₘ) increases, while the maximum velocity (Vₘâ‚â‚“) remains unchanged [21] [15] [25]. This means that at high substrate concentrations, the inhibition can be overcome. This contrasts with uncompetitive and mixed inhibition, where Vₘâ‚â‚“ is decreased [2].

What are the common methods to detect and characterize product inhibition?

The standard method involves measuring the initial velocity of the enzyme reaction under different conditions [26]. This typically includes:

- Varying substrate concentrations at multiple, fixed concentrations of the product (inhibitor) [26] [27].

- Fitting the collected velocity data to inhibition models (e.g., Michaelis-Menten equations modified for inhibition) to determine kinetic constants like Káµ¢ (inhibition constant) and ICâ‚…â‚€ (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) [26] [27].

- A modern, efficient approach termed 50-BOA uses a single inhibitor concentration greater than the ICâ‚…â‚€ to precisely estimate inhibition constants, significantly reducing experimental workload [26].

How can I mitigate product inhibition in my bioreactor?

Several engineering strategies can help overcome product inhibition:

- Membrane Bioreactors: Using a semi-permeable membrane to continuously separate the inhibitory product from the reaction mixture while retaining the enzyme and substrate [21] [22].

- In Situ Product Recovery (ISPR): Integrating techniques like liquid-liquid extraction or vacuum extraction to remove the product as it is formed [22].

- Metabolic Engineering: Engineering microbial hosts to be more tolerant to the product and to enhance export mechanisms [23] [24]. For example, a study on cadaverine production engineered E. coli for improved tolerance and yield [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexpectedly Low Reaction Yield

Potential Cause: Severe product inhibition reducing the effective reaction rate over time.

Solutions:

- Confirm the Cause: Measure reaction velocity at different time points. A progressive slowdown that correlates with product accumulation strongly indicates product inhibition [21].

- Characterize the Inhibition: Determine the ICâ‚…â‚€ and inhibition constant (Káµ¢) of your product [27]. This quantitative data is crucial for modeling and scaling up your process. The 50-BOA method is recommended for efficient characterization [26].

- Adapt the Process: Implement a fed-batch or continuous reactor coupled with a product separation method, such as a membrane, to maintain low product concentration in the reactor [21] [22].

Problem: Inconsistent Kinetic Data

Potential Cause: Neglecting to account for product inhibition in initial rate studies, leading to an overestimation of the apparent Kₘ [21] [27].

Solutions:

- Design Robust Experiments: Ensure initial velocity measurements are taken at a very early stage of the reaction when the product concentration is negligible [21].

- Use Comprehensive Models: When fitting your kinetic data, employ equations that include an inhibition term for the product. For competitive product inhibition, the model is:

v = (Vₘâ‚â‚“ * [S]) / ( Kₘ * (1 + [P]/Káµ¢) + [S] )[21] [25]. - Employ Advanced Assays: Consider using a unified assay platform, like a quantitative FRET (qFRET) method, to determine all kinetic parameters and interaction affinities simultaneously, reducing inter-method variability [27].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining ICâ‚…â‚€ for a Product Inhibitor

Principle: This protocol determines the concentration of a product that reduces the enzyme's activity by 50% under a specific substrate concentration.

Procedure:

- Prepare a reaction mixture with a fixed, known concentration of substrate (often near the Kₘ value) and enzyme [26].

- Set up a series of reactions with increasing concentrations of the product (inhibitor).

- Measure the initial velocity of each reaction.

- Plot the percentage of enzyme activity (relative to a control with no inhibitor) against the logarithm of the product concentration.

- Fit the data to a sigmoidal curve and determine the ICâ‚…â‚€ value from the plot.

Protocol 2: Single-Inhibitor Concentration Method (50-BOA) for Precise Inhibition Constant Estimation

Principle: This modern protocol allows for accurate and precise estimation of inhibition constants using a single, optimally chosen inhibitor concentration, drastically reducing the number of experiments needed [26].

Procedure:

- Estimate ICâ‚…â‚€: First, perform an initial experiment as described in Protocol 1 to get an approximate ICâ‚…â‚€ value.

- Set Up Reactions: For a single inhibitor concentration

[I] > IC₅₀, measure the initial reaction velocity across a wide range of substrate concentrations[S]. - Fit the Data: Fit the collected velocity and substrate concentration data to the mixed inhibition model (Equation 1 below), incorporating the relationship between IC₅₀, Kₘ, and the inhibition constants (Kᵢc and Kᵢu) during the fitting process [26].

- Extract Parameters: The fitting algorithm will output the estimated values for Káµ¢c and Káµ¢u.

The General Mixed Inhibition Model:

Vâ‚€ = (Vₘâ‚â‚“ * Sâ‚œ) / [ Kₘ * (1 + Iâ‚œ/Káµ¢c) + Sâ‚œ * (1 + Iâ‚œ/Káµ¢u) ] [26]

Data Presentation

Table 1: Kinetic Signatures of Reversible Inhibition Types

| Inhibition Type | Binding Site | Effect on Vₘâ‚â‚“ | Effect on Kₘ (Apparent) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive [15] [2] | Active Site | Unchanged | Increases |

| Non-competitive [2] | Allosteric Site (equal affinity for E and ES) | Decreases | Unchanged |

| Uncompetitive [2] | Allosteric Site (only ES) | Decreases | Decreases |

| Mixed [2] | Allosteric Site (different affinity for E and ES) | Decreases | Increases or Decreases |

Table 2: Strategies to Overcome Product Inhibition in Bioprocessing

| Strategy | Method | Example | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactor Design [22] | Membrane Bioreactor | Continuous lactic acid fermentation [22] | Product must differ in size/solubility from substrate and enzyme. |

| In Situ Recovery [22] | Liquid-Liquid Extraction / Vacuum Extraction | Removal of 1,3-propanediol or ethanol [22] | Requires a solvent or condition that does not harm the catalyst. |

| Host Engineering [23] [24] | Metabolic Engineering & Adaptive Evolution | Engineering E. coli for high cadaverine tolerance [24] | A robust, genetically tractable host organism is required. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram: Metabolic Pathway with End-Product Inhibition

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Inhibition Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Product Inhibition Studies |

|---|---|

| Membrane Bioreactor | A reactor system that uses a semi-permeable membrane to continuously separate inhibitory products from the reaction vessel, alleviating feedback inhibition [21] [22]. |

| qFRET Assay Components (CyPet/YPet tagged proteins) | A unified assay platform using Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) to quantitatively determine enzyme kinetics, substrate affinity, and product-inhibitor binding constants in a single, compatible system [27]. |

| ICâ‚…â‚€-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA) | A computational and experimental methodology that uses a single, optimal inhibitor concentration (greater than ICâ‚…â‚€) to precisely estimate inhibition constants, drastically reducing experimental workload [26]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Computational models used to predict metabolic capabilities of microbial cell factories, identify bottlenecks, and derive metabolic engineering strategies to optimize flux and circumvent product inhibition [23]. |

| Bendazac | Bendazac, CAS:20187-55-7, MF:C16H14N2O3, MW:282.29 g/mol |

| Moschamine | Moschamine, CAS:193224-22-5, MF:C20H20N2O4, MW:352.4 g/mol |

Escherichia coli employs a sophisticated, multi-layered regulatory network to assimilate nitrogen efficiently and respond to environmental changes. At the core of this system lies feedback regulation, where end-products of assimilation dynamically control enzyme activity and gene expression. This precise control allows the bacterium to conserve energy and maintain metabolic homeostasis, particularly under nitrogen-limiting conditions. Understanding these regulatory mechanisms, especially the phenomenon of product inhibition, provides valuable insights for overcoming similar challenges in catalytic biosynthesis research, where accumulation of target compounds often limits process efficiency and yield.

Core Pathways and Key Components

E. coli possesses two primary pathways for ammonium assimilation into glutamate, each with distinct kinetic properties and regulatory logic.

Table 1: Key Ammonium Assimilation Pathways in E. coli

| Pathway Name | Enzymes Involved | Reaction Catalyzed | Affinity for NH₄⺠| Energy Cost | Primary Functional Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate Dehydrogenase (GDH) Pathway | GDH | NH₄⺠+ 2-oxoglutarate + NADPH → Glutamate | Low (~1 mM Km) [28] | Lower (No ATP consumed) | Nitrogen-rich conditions [28] |

| GS-GOGAT Pathway | Glutamine Synthetase (GS) & Glutamate Synthase (GOGAT) | GS: Glutamate + NH₄⺠+ ATP → GlutamineGOGAT: Glutamine + 2-oxoglutarate + NADPH → 2 Glutamate | High (~0.1 mM Km for GS) [28] | Higher (1 ATP per Glutamine synthesized) | Nitrogen-limiting conditions [28] |

The hierarchical regulatory network revolves around several key proteins and small molecule signals.

Table 2: Key Regulatory Components in E. coli Nitrogen Assimilation

| Component | Type | Function in Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| GlnB (PII) & GlnK | Signal Transduction Protein | Sense intracellular nitrogen status (via 2-oxoglutarate and glutamine levels); regulate ATase, UTase, and transporter activity [29] [28]. |

| NtrC | Response Regulator | Master transcriptional activator of the nitrogen stress response; activates genes for alternative nitrogen scavenging [30] [28]. |

| GS (GlnA) | Metabolic Enzyme & Regulation Target | Key assimilatory enzyme; activity is post-translationally regulated by adenylylation, which is controlled by the PII proteins and UTase/UR enzyme [28]. |

| ppGpp | Signal Molecule ("Alarmone") | Effector of the stringent response; synthesis is tied to nitrogen starvation via NtrC-dependent activation of relA [30]. |

| Glutamine | Metabolite (End-Product) | Key signaling molecule; high levels indicate nitrogen sufficiency, triggering feedback inhibition on GS and repression of NtrC-dependent transcription [28]. |

Regulatory Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The system integrates multiple regulatory layers to provide a robust and dynamic response.

Post-translational Regulation: The GS Regulatory Cascade

The activity of Glutamine Synthetase is rapidly modulated via reversible covalent modification in response to nitrogen availability.

Figure 1: Post-translational Regulation of Glutamine Synthetase. Under nitrogen sufficiency, the UTase/UR enzyme is active in its uridylyl-removing mode, leading to unmodified GlnK (PII). GlnK stimulates ATase to adenylylate GS, rendering it inactive. During nitrogen starvation, UTase/UR is inactive, allowing GlnK to be uridylylated (GlnK-UMP). This form stimulates ATase to deadenylylate GS, activating it for nitrogen assimilation [28].

Transcriptional Regulation and System Coupling

During nitrogen limitation, a two-component system composed of the sensor kinase NtrB and the response regulator NtrC is activated. Phosphorylated NtrC (NtrC~P) then activates the transcription of genes involved in scavenging alternative nitrogen sources [30] [28]. A critical coupling mechanism was discovered between the nitrogen stress response and the stringent response: NtrC~P directly binds to and activates the transcription of relA, the primary enzyme responsible for synthesizing the alarmone ppGpp [30]. This directly links nitrogen status to the global stringent response.

Figure 2: Coupling of Nitrogen Stress and Stringent Responses. Nitrogen limitation activates NtrB, which phosphorylates NtrC. NtrC~P not only activates transcription of traditional nitrogen-stress genes but also directly activates transcription of relA. Increased RelA synthesis leads to elevated levels of ppGpp, thereby activating the stringent response and globally altering cell physiology to cope with nitrogen stress [30].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: Why is my engineered E. coli strain showing poor growth or low yield under nitrogen-fixing or nitrogen-limiting conditions?

- Potential Cause: Inefficient regulatory coupling or metabolic burden. The host's native regulatory systems may not be optimally integrated with heterologous pathways (e.g., introduced nitrogenase genes), leading to improper expression or energy drain.

- Solution:

- Verify Regulatory Compatibility: Ensure heterologous genes are placed under promoters recognized by the host's Ntr system (e.g., σ54-dependent promoters) [31].

- Modulate PII Proteins: Consider engineering

glnBorglnKmutants to manipulate the signal transduction cascade favoring pathway activation [29] [28]. - Optimize Energy Supply: Transcriptomic data suggest that under nitrogen-fixation conditions, flux through the pentose phosphate pathway may increase to supply NADPH. Engineering central carbon metabolism (e.g., overexpressing

zwffor glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) can enhance reducing power supply [31].

FAQ 2: How can I overcome product inhibition in a metabolic pathway for nitrogenous compound synthesis (e.g., cadaverine)?

- Potential Cause: Accumulation of the target product (e.g., cadaverine) inhibits the activity of key enzymes in the biosynthesis pathway or suppresses precursor synthesis, halting production [24].

- Solution:

- Develop Robust Hosts: Use mutagenesis (e.g., ARTP mutagenesis) and selection to generate host strains with higher tolerance to the target inhibitor [24].

- Engineer Efflux Systems: Overexpress native or heterologous exporter genes to actively transport the inhibitory product out of the cell, reducing intracellular concentration [24].

- Relieve Precursor Inhibition: Use transcriptome analysis to identify pathway bottlenecks. For example, if product inhibition suppresses synthesis of a key precursor like lysine (for cadaverine), engineer regulatory genes (e.g.,

PuuR) or enhance glycolytic flux to restore precursor supply [24].

FAQ 3: Why are the gene expression changes I observe in my NtrC mutant different from established models?

- Potential Cause: Overlooked indirect effects or interactions with other global regulators. NtrC directly activates

relA, thereby elevating ppGpp levels, which globally alter transcription [30]. - Solution:

- Monitor ppGpp Levels: Measure intracellular ppGpp concentrations in your mutant versus wild-type strain under identical conditions.

- Profile Stringent Response Genes: Use RNA-seq or qPCR to check the expression of known ppGpp-regulated genes to confirm whether the observed changes are a direct consequence of NtrC or an indirect effect via the stringent response [30].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Measuring Glutamine Synthetase (GS) Activity and Adenylylation State

Principle: GS activity can be measured by its biosynthetic reaction (γ-glutamyl transferase assay is a common coupled assay). The adenylylation state is determined by comparing activity under conditions that favor the adenylylated (inactive) versus deadenylylated (active) form.

Materials:

- Lysis Buffer: 50 mM imidazole-HCl (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM MnCl2.

- Assay Buffer A (for Deadenylylated GS): 50 mM imidazole-HCl (pH 7.0), 50 mM L-glutamate, 100 mM NHâ‚‚OH, 20 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ADP, 0.4 mM MnCl2.

- Assay Buffer B (for Total GS): 50 mM imidazole-HCl (pH 7.0), 150 mM L-glutamate, 100 mM NHâ‚‚OH, 60 mM MgCl2.

- Stop Solution: 1 M FeCl3, 0.5 M HCl, 0.25 M Trichloroacetic acid.

Procedure:

- Cell Extract Preparation: Grow E. coli culture to mid-log phase under experimental conditions. Harvest cells, resuspend in Lysis Buffer, and disrupt by sonication. Centrifuge to remove cell debris.

- Activity Assay:

- For each sample, set up two reaction tubes.

- Tube 1 (Deadenylylated GS): Mix 100 µL of cell extract with 400 µL of Assay Buffer A.

- Tube 2 (Total GS): Mix 100 µL of cell extract with 400 µL of Assay Buffer B.

- Incubate all tubes at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Stop the reaction by adding 500 µL of Stop Solution.

- Measurement: Centrifuge the stopped reactions to remove precipitate. Measure the absorbance of the supernatant at 540 nm. The amount of γ-glutamylhydroxamate formed is proportional to GS activity.

- Calculation: The activity in Tube 1 represents the fraction of active, deadenylylated GS. The activity in Tube 2 represents the total GS activity regardless of adenylylation state. The adenylylation state is expressed as the ratio of activities: (1 - ActivityTube1/ActivityTube2) [28].

Protocol: Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to Map NtrC Binding Sites

Principle: This protocol, adapted from [30], cross-links proteins to DNA in vivo, immunoprecipitates the protein-DNA complexes with an antibody against the protein of interest (e.g., FLAG-tagged NtrC), and then identifies the bound DNA sequences by high-throughput sequencing.

Materials:

- E. coli strain with chromosomally encoded, epitope-tagged NtrC (e.g., NtrC-3xFLAG).

- Anti-FLAG M2 antibody and compatible magnetic beads.

- Cross-linking solution: 1% formaldehyde.

- Lysis buffers, Wash buffers, Elution buffer.

- Protease K, RNase A.

- Equipment for sonication (to shear DNA) and PCR/qPCR or library prep for sequencing.

Procedure:

- Cross-linking: Grow cells to desired density under nitrogen-starvation conditions. Add formaldehyde directly to the culture (final concentration 1%) and incubate for 20-30 minutes at room temperature to cross-link. Quench the cross-linking with glycine.

- Cell Lysis and Sonication: Harvest cells, wash, and resuspend in lysis buffer. Lyse cells by sonication. Sonicate the lysate to shear DNA into fragments of 200-500 bp.

- Immunoprecipitation: Clarify the lysate by centrifugation. Incubate the supernatant with anti-FLAG antibody conjugated to magnetic beads overnight at 4°C.

- Washing and Elution: Wash the beads extensively with a series of wash buffers to remove non-specifically bound DNA. Elute the protein-DNA complexes from the beads.

- Reverse Cross-linking and DNA Purification: Reverse the cross-links by incubating the eluate at 65°C overnight. Treat with Protease K and RNase A. Purify the DNA.

- Analysis: The purified DNA can be analyzed by qPCR for specific targets or used to prepare a library for high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) to map all binding sites genome-wide [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Nitrogen Assimilation in E. coli

| Reagent / Strain | Function / Feature | Key Application / Utility |

|---|---|---|

| ASKA Library Strains | Collection of E. coli strains with His-tagged versions of ORFs [32]. | Source for purification of enzymes like GlnA, GlnK, NtrC for in vitro assays. |

| NtrC-FLAG Strain | E. coli with a chromosomal 3xFLAG tag on glnG (NtrC) [30]. |

Mapping genome-wide binding sites of NtrC via ChIP-seq under different nitrogen conditions. |

| ΔglnG (ΔntrC) & ΔrelA Strains | Isogenic knockout mutants of key regulatory genes. | Dissecting the specific roles of NtrC and RelA/ppGpp in the regulatory network [30]. |

| Anti-FLAG M2 Antibody | Monoclonal antibody against the FLAG epitope. | Immunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged NtrC in ChIP experiments [30]. |

| Anti-E. coli RelA Antibody | Monoclonal antibody against E. coli RelA protein [30]. | Detecting RelA protein accumulation via Western blotting under different nitrogen regimes. |

| Mass-Spectrometry Compatible Assay Buffers | Standardized buffer (e.g., 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) with physiological metabolite concentrations [32]. | High-throughput screening of allosteric effectors on enzyme activities in central nitrogen metabolism. |

| 3-Deoxy-galactosone | 3-Deoxy-galactosone, MF:C6H10O5, MW:162.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| UDP-GlcNAc | UDP-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine Supplier for Research |

Methodological Arsenal: From Screening to Engineering Resistance

In the field of catalytic biosynthesis research, end-product inhibition significantly hampers process efficiency and yield. This technical support article details how simulated enzyme progress curves serve as an advanced screening tool, enabling researchers to overcome product inhibition and identify effective enzyme inhibitors with greater accuracy and reduced resource expenditure.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues and Solutions in Progress Curve Experiments

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low observed inhibition in endpoint assays | Assay read at suboptimal time point; high product concentration causing inhibition. | Use simulation tools to identify the time of maximum difference (Δmax[P]) in product concentration between inhibited and uninhibited reactions, which often occurs at >75% substrate conversion [33]. |

| Poor Z-factor in HTS | High experimental noise; low signal-to-background ratio; suboptimal observation window. | Simulate progress curves to tune reactant concentrations and identify an observation window that maximizes the separation between hits and controls [33]. |

| Inconsistent IC50 values | Underlying theory based on initial reaction rates is violated at extended reaction times. | Base interpretation on full progress curve analysis instead of the Michaelis-Menten initial velocity equation. Use simulation tools that account for reversibility and product inhibition [33]. |

| Difficulty identifying true inhibitors | Assay artifacts and false positives obscure true enzyme modulation effects. | Apply a 3-point method of kinetic analysis, using enzymology principles on three data points from the reaction progress to distinguish true inhibitors from false positives [34]. |

Interpreting Simulated Progress Curves

The graph below illustrates a simulated progress curve for an uninhibited enzyme reaction compared to one with competitive inhibition, highlighting the point of maximum difference in product formation (Δmax[P]).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Methodology

Q: What is the primary advantage of using simulated progress curves for inhibitor screening? A: The primary advantage is significantly increased resource efficiency. Traditional brute-force virtual or experimental screening is expensive and time-consuming. An approach combining molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with active learning, for instance, has been shown to reduce the number of compounds requiring experimental testing to less than 20, cutting computational costs by approximately 29-fold [35].

Q: How can progress curve analysis help overcome product inhibition in biosynthesis? A: Progress curve analysis allows researchers to model and predict the extent to which accumulating product slows down the reaction. This insight is crucial for designing strategies to mitigate inhibition, such as in-situ product removal or engineering more robust enzymes. For example, in cadavarine production, overcoming end-product inhibition through host engineering and process optimization led to a record yield of 58.7 g/L [24].

Technical Implementation

Q: My high-throughput screening (HTS) assay has a low Z-factor. How can progress curve simulation help?

A: Simulation tools allow you to adjust key reaction variables and parameters—such as initial substrate concentration [S], enzyme concentration [E], and Km—and visually determine the conditions that maximize the difference (Δ[P]) between inhibited and uninhibited reactions [33]. Optimizing for the point of Δmax[P] improves the signal-to-background ratio and separation, which directly enhances the Z-factor.

Q: Why does my observed inhibition (%) change depending on when I read the assay? A: Observed inhibition is not constant throughout a reaction; it is a function of time and the degree of substrate conversion. The graph below shows how the observed inhibition for different mechanisms varies as the reaction proceeds. This is why identifying the optimal readout time via simulation is critical for accurate assessment of inhibitor potency [33].

Data Analysis

Q: What is the "3-point method" of kinetic analysis and how does it improve screening? A: The 3-point method is a post-Michaelis-Menten approach where each screened reaction is probed at three different time points, none of which are required to be during the initial constant-velocity period. This method uses enzymology principles to identify assay artifacts and accurately distinguish true enzyme modulators from false positives, thereby drastically improving hit success rates and the robustness of the screening data [34].

Q: How can I account for different modes of inhibition (e.g., competitive, uncompetitive) in my simulations?

A: Advanced simulation tools in spreadsheet format allow for interactive adjustment of parameters for different inhibition modes, including competitive (Kic), uncompetitive (Kiu), and mixed inhibition. The tool simulates the progress curves for each mechanism, allowing for direct comparison of Δ[P] and determination of Δmax[P] for each type [33].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Active Learning Framework for Virtual Inhibitor Screening

This methodology uses molecular dynamics (MD) and active learning to efficiently navigate chemical space and identify potent inhibitors [35].

- Generate a Receptor Ensemble: Run a long-timescale (≈100 µs) MD simulation of the target enzyme. From this simulation, extract multiple snapshots (e.g., 20 structures) to account for protein flexibility and conformational states [35].

- Initial Docking and Scoring: Dock a small, initial subset (e.g., 1%) of a compound library (e.g., DrugBank) to each structure in the receptor ensemble. Score the resulting poses using a target-specific score (e.g., an empirical "h-score" that rewards occlusion of the active site and key interaction distances) rather than a generic docking score [35].

- Active Learning Cycle: Rank the candidates based on the target-specific score. Select the top-ranking compounds and run more extensive MD simulations (e.g., 100 ns per ligand) for dynamic h-scoring. Use the results to select the next set of compounds for testing. Repeat this cycle until known or potent inhibitors consistently rank at the top [35].

- Experimental Validation: The final shortlist of top-ranked compounds (often less than 20) requires experimental validation (e.g., measuring IC50).

Protocol 2: Setting Up an In-Situ Product Removal System

This protocol is directly applicable to overcoming co-product inhibition in enzymatic biosynthesis, as demonstrated in disproportionation reactions catalyzed by Old Yellow Enzymes (OYEs) [9].

- Identify Inhibitory Co-product: Determine if a reaction co-product acts as a strong inhibitor. For OYEs, electron-rich phenols form stable charge-transfer complexes with the flavin cofactor, severely inhibiting the enzyme [9].

- Select a Scavenger: Choose a polymeric adsorbent suitable for the co-product. For phenolic compounds, MP-Carbonate has been successfully used [9].

- Run the Reaction under Optimized Conditions:

- Prepare a degassed buffer solution in a sealed vial under an inert atmosphere (e.g., argon).

- Add the substrate, enzyme, and the MP-carbonate scavenger (e.g., 40 equivalents relative to its loading capacity).

- Agitate the mixture for the desired reaction time (e.g., 24 hours at 30°C).

- The scavenger will continuously remove the inhibitory phenol from the solution, preventing it from binding to the enzyme's active site and driving the reaction to high conversion (>90%) [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Receptor Ensemble | A collection of protein structures from MD simulations that accounts for flexible binding pockets, crucial for improving virtual screening accuracy [35]. | Used in docking to avoid bias from a single, static crystal structure. |

| Target-Specific Score (e.g., h-score) | An empirical or machine-learned scoring function tailored to a specific protein target, evaluating features critical for inhibition rather than just binding affinity [35]. | More accurate ranking of potential inhibitors than generic docking scores. |

| MP-Carbonate | A polymeric adsorbent with a high loading capacity for phenolic compounds, used for in-situ co-product removal [9]. | Scavenges inhibitory phenol in OYE-catalyzed disproportionation reactions, enabling high conversion. |

| Progress Curve Simulation Tool | A spreadsheet-based tool that models the time progress of enzyme-catalyzed reactions, allowing adjustment of variables and parameters [33]. | Optimizing HTS conditions and identifying the optimal time for assay readout. |

| Robust Engineered Host | A microbial strain engineered for high tolerance to inhibitory end-products through mutagenesis and metabolic engineering [24]. | Production of platform chemicals like cadaverine at high titers by mitigating end-product inhibition. |

| Ecliptasaponin D | Ecliptasaponin D, MF:C36H58O9, MW:634.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ganoderenic acid C | Ganoderenic acid C, MF:C30H44O7, MW:516.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In catalytic biosynthesis research, product inhibition is a fundamental regulatory mechanism and a significant challenge for maximizing product yield. This form of negative feedback control occurs when the end product of an enzymatic reaction binds to the enzyme, reducing its activity and limiting the overall efficiency of the biosynthetic pathway [27]. Traditional methods for studying these kinetics often require multiple, disparate technologies to characterize the various parameters, leading to compatibility issues with integrated data and standard errors [36] [27].

The development of Quantitative FRET (qFRET) technology provides a unified solution to this challenge. qFRET is a high-throughput assay platform that enables the determination of protein interaction affinity, enzymatic kinetics, and pharmacological parameters within a single, standardized system [37]. By utilizing a cross-wavelength correlation coefficiency approach to dissect the sensitized FRET signal from the total fluorescence signal, qFRET allows researchers to obtain comprehensive kinetic parameters—including the real ( KM ), ( K{cat} ), and inhibitor constant ( K_i )—under identical experimental conditions, thereby providing more accurate and reliable characterization of product inhibition mechanisms [27].

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My FRET signal is weak or inconsistent. What could be the cause?

A: A weak FRET signal can result from several factors. First, verify the fluorophore pair distance. FRET efficiency is highly sensitive to the distance between donor and acceptor fluorophores, which should typically be within 1–10 nm [37]. Second, check the orientation of dipoles; the energy transfer efficiency depends on the relative orientation of the donor and acceptor transition dipoles. Third, confirm the spectral overlap between donor emission and acceptor excitation spectra. Finally, ensure that your protein fusion constructs do not sterically hinder the interaction you intend to measure [38].

Q2: How can I accurately distinguish the FRET signal from direct emission background?

A: Use the cross-wavelength correlation coefficiency method to dissect the sensitized FRET signal. Determine the cross-talk ratio of the donor (α) as the ratio of the donor's emission at the FRET wavelength (530 nm) to its emission at the donor wavelength (475 nm) when excited at the donor excitation wavelength (414 nm): ( α = I{d530/414} / I{d475/414} ). Similarly, determine the cross-talk ratio of the acceptor (β) as the ratio of the acceptor's emission at the FRET wavelength when excited at the donor excitation wavelength (414 nm) to its emission at the FRET wavelength when excited at the acceptor excitation wavelength (475 nm): ( β = I{a530/414} / I{a530/475} ). The absolute FRET signal (EmFRET) can then be calculated as: ( EmFRET = I{total} - α × FL{DD} - β × FL{AA} ), where ( I{total} ) is the total emission at the FRET wavelength, ( FL{DD} ) is the donor emission at the donor wavelength, and ( FL{AA} ) is the acceptor emission at the FRET wavelength with acceptor excitation [36] [27].

Q3: What are the advantages of qFRET over traditional methods like SPR or ITC for studying product inhibition?

A: qFRET offers several distinct advantages. It allows real-time monitoring of enzymatic reactions and inhibition directly in solution, unlike SPR which requires surface immobilization that can alter protein conformation and binding kinetics [36]. qFRET requires smaller protein quantities compared to ITC, which needs micromolar range concentrations [36] [37]. Most importantly, qFRET enables the determination of multiple parameters (( KD ), ( K{cat} ), ( KM ), ( Ki ), IC50) within a single assay platform, eliminating technical variations between different methods and providing more reliable kinetics for product inhibition studies [37] [27].

Q4: How do I validate that my qFRET assay is accurately reporting on product inhibition?

A: Implement these validation steps. First, determine cross-talk coefficients (α and β) for each new batch of purified proteins to account for any variations in fluorophore properties [27]. Second, include a non-cleavable mutant substrate as a negative control to establish baseline FRET efficiency [38]. Third, correlate initial findings with established methods if possible; for instance, researchers have found excellent agreement between qFRET-derived KD values and those determined by SPR and ITC [36]. Finally, perform dose-response experiments with known inhibitors to verify that the assay can accurately determine IC50 values [27].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Protease Kinetics and Product Inhibition Using qFRET

This protocol outlines the procedure for determining the kinetics of SENP1 protease activity and its inhibition by the mature SUMO1 product, based on established qFRET methodologies [39] [27].

Step 1: Construct Preparation Clone genes encoding CyPet-(pre-SUMO1)-YPet FRET substrate and SENP1 catalytic domain (SENP1c) into appropriate expression vectors (e.g., pET28(b)). Verify all constructs by DNA sequencing.

Step 2: Protein Expression and Purification Express proteins in E. coli BL21(DE3). Induce expression with 1 mM IPTG when cultures reach OD600 of 0.5-0.6. Purify proteins using affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag purification) followed by buffer exchange into appropriate reaction buffer.

Step 3: Determine Cross-Talk Coefficients

- Donor cross-talk (α): Using purified CyPet-SUMO1, measure emission at 475 nm (( I{d475/414} )) and 530 nm (( I{d530/414} )) with excitation at 414 nm. Calculate ( α = I{d530/414} / I{d475/414} ). A typical value is approximately 0.332 [27].

- Acceptor cross-talk (β): Using purified YPet, measure emission at 530 nm with excitation at 414 nm (( I{a530/414} )) and 475 nm (( I{a530/475} )). Calculate ( β = I{a530/414} / I{a530/475} ). A typical value is approximately 0.026 [27].

Step 4: Enzymatic Reaction and Real-Time Monitoring Set up reactions in a 384-well plate with a fixed concentration of CyPet-(pre-SUMO1)-YPet substrate and varying concentrations of SENP1c. To study product inhibition, include reactions with fixed concentrations of both substrate and enzyme while titrating in the product (mature SUMO1). Monitor fluorescence in a plate reader with excitation at 414 nm and dual emission detection at 475 nm and 530 nm.

Step 5: Data Analysis

- Calculate the absolute FRET signal (EmFRET) at each time point using the formula: ( EmFRET = I{530/414} - α × I{475/414} - β × I_{530/475} ).

- Plot EmFRET versus time to determine initial reaction velocities at different substrate concentrations.

- Fit the velocity data to the Michaelis-Menten equation to obtain ( KM ) and ( V{max} ) values.

- For product inhibition, analyze the reduction in initial velocity with increasing product concentration to determine the inhibitor constant ( K_i ) [27].

Protocol 2: Determining Protein-Protein Interaction Affinity (KD)

This protocol describes how to determine the dissociation constant (( K_D )) for protein-protein interactions using qFRET [36].

Step 1: Sample Preparation Prepare a constant concentration of donor-labeled protein and titrate with increasing concentrations of acceptor-labeled protein across a suitable range (e.g., donor:acceptor ratio from 4:1 to 1:40).

Step 2: Fluorescence Measurement For each sample, measure three fluorescence values:

- ( FL_{DD} ): Donor emission (475 nm) with donor excitation (414 nm)

- ( FL_{DA} ): Acceptor emission (530 nm) with donor excitation (414 nm)

- ( FL_{AA} ): Acceptor emission (530 nm) with acceptor excitation (475 nm)

Step 3: FRET Signal Calculation Calculate the absolute FRET signal (EmFRET) for each sample using the formula: ( EmFRET = FL{DA} - α × FL{DD} - β × FL_{AA} ), where α and β are the predetermined cross-talk coefficients.

Step 4: KD Calculation Plot the EmFRET values against the acceptor concentration and fit the binding curve to appropriate binding models (e.g., one-site specific binding) to determine the ( KD ) value. This approach has shown excellent agreement with ( KD ) values determined by SPR and ITC [36].

Data Presentation

Quantitative Kinetics Parameters Determined by qFRET

qTable 1: Exemplary kinetic parameters for SENP1 protease determined by qFRET.

| Parameter | Description | Value | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( K_M ) | Michaelis constant for pre-SUMO1 substrate | 1.13 µM | Fixed [SENP1c], varying [CyPet-(pre-SUMO1)-YPet] [27] |

| ( K_{cat} ) | Catalytic constant | 0.017 sâ»Â¹ | Fixed [SENP1c], varying [CyPet-(pre-SUMO1)-YPet] [27] |

| ( K{cat}/KM ) | Catalytic efficiency | 0.015 µMâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹ | Calculated from ( K{cat} ) and ( KM ) [27] |

| ( K_i ) | Dissociation constant for product (SUMO1) inhibition | 2.54 µM | Fixed [Substrate] & [SENP1c], varying [SUMO1] [27] |

| IC₅₀ | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration of SUMO1 | 6.27 µM | Fixed [Substrate] & [SENP1c], varying [SUMO1] [27] |

Key Instrumentation and Reagent Specifications

qTable 2: Essential research reagents and equipment for qFRET assays. [36] [37] [38]

| Category | Item | Specification/Example | Function/Role in Assay |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorophores | Donor Fluorescent Protein | CyPet (Ex/Em: 414/475 nm) | FRET energy donor [36] |

| Acceptor Fluorescent Protein | YPet (Ex/Em: 475/530 nm) | FRET energy acceptor [36] | |

| Alternative FRET Pair | AcGFP1 (Donor) & mCherry (Acceptor) | Red-shifted pair for reduced autofluorescence [38] | |

| Expression System | Plasmid Vectors | pET28(b), pLVX-AcGFP1-N1 | Protein expression and fusion construct creation [38] [27] |

| Expression Host | E. coli BL21(DE3) | Recombinant protein expression [27] | |

| Hardware | Detection Instrument | Fluorescence plate reader (capable of 384-well plates) | High-throughput fluorescence measurement [36] [37] |

| Required Filters | Ex 414 ± 10 nm, Em 475 ± 20 nm, Em 530 ± 15 nm | Specific excitation and emission wavelength detection [36] |

Essential Visualizations

qFRET Signal Calculation Workflow

qFRET Signal Calculation Workflow

Product Inhibition Mechanism

qFRET Application in Product Inhibition

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Challenges in Developing Feedback-Resistant Enzymes

Problem: Engineered enzyme exhibits poor catalytic activity despite feedback resistance.

| Possible Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Disruption of Active Site | Mutations near allosteric site distort catalytic site geometry [40]. | Perform coupled rational design; re-optimize active site residues after introducing feedback-resistant mutation [41]. |

| Reduced Protein Stability | Amino acid substitutions decrease overall protein folding stability [40]. | Use computational tools (FoldX, Rosetta) to calculate folding free energy change and select stabilizing mutations [40]. |

| Incorrect Screening | Screening method does not replicate true industrial process conditions [42]. | Implement HPLC-based screening mimicking actual process parameters (pH, temperature, substrate concentration) [42]. |

Problem: Introduced mutation fails to confer expected feedback resistance.

| Possible Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Allosteric Disruption | Single mutation insufficient to disrupt effector binding; other residues maintain interaction [43]. | Create double or triple mutants based on structural analysis of allosteric site [40]. |

| Synergistic Regulation | Enzyme remains regulated via transcriptional control or phosphorylation, independent of allostery [43]. | Engineer regulatory elements (e.g., promoter) or use constitutive expression system alongside protein engineering [43]. |

| Unexpected Inhibition Mechanism | Inhibition occurs via unusual mechanism (e.g., product release blockage) not targeted by design [44]. | Conduct thorough kinetic characterization (steady-state and transient) to identify true inhibition mechanism before engineering [44]. |

Problem: Engineered enzyme performs well in vitro but fails in whole-cell system.

| Possible Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Metabolite Degradation | Key pathway intermediates or products are rapidly degraded by other cellular enzymes [43]. | Engineer host background by knocking out degradative enzymes or competing pathways [43]. |

| Suboptimal Enzyme Expression | Codon usage, mRNA stability, or promoter strength limit enzyme expression in host [41]. | Optimize codon usage, use stronger promoters, and fine-tune expression levels to balance metabolic burden [41]. |

| Insufficient Precursor Supply | Metabolic precursors (PEP, E4P) are limited, constraining flux through engineered pathway [40]. | Engineer host to enhance precursor supply (e.g., overexpress translketolase for E4P) [40]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between rational design and directed evolution for creating feedback-resistant enzymes?

A1: Rational design uses knowledge of enzyme structure-function relationships to make targeted mutations in allosteric sites, often leveraging crystal structures with bound effectors [40] [41]. Directed evolution mimics natural selection through random mutagenesis and high-throughput screening to accumulate beneficial mutations without requiring prior structural knowledge [42]. Modern approaches often combine both strategies in semi-rational design, using computational tools to create "smart" libraries focused on specific protein regions [41].

Q2: Which computational tools are most valuable for predicting mutations that confer feedback resistance?

A2: Key computational tools include:

- FoldX and Rosetta: Calculate protein folding free energy changes to assess mutation stability [40].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Model atomic-level movements to study allosteric mechanisms and inhibitor binding [44].

- Markov State Models (MSM): Analyze MD simulation data to identify and characterize kinetically distinct states in allosteric pathways [44].

- Homology Modeling: Predict tertiary structures when experimental structures are unavailable [40].

Q3: How can we quantitatively compare the performance of different feedback-resistant enzyme variants?

A3: Performance is quantified using these key parameters in enzyme kinetics assays:

- Residual Activity at High Inhibitor Concentration: Percentage of activity remaining at saturating inhibitor levels (e.g., 5 mM tyrosine) [40].

- Apparent Inhibition Constant (Ki,app): Measure of inhibitor affinity for engineered versus wild-type enzyme [43].

- Specific Activity in Absence of Inhibitor: Ensures catalytic efficiency is not compromised [40].

The table below summarizes performance data for exemplary feedback-resistant mutants of DAHPS (AroF) from Corynebacterium glutamicum:

Table: Quantitative Comparison of Feedback-Resistant DAHPS (AroF) Variants

| Variant | Residual Activity at 5 mM Tyr | Specific Activity (No Tyr) | Key Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | Very Low (Baseline) | 100% (Reference) | N/A |

| E154N | >80% | >50% | Direct interference with binding |

| P155L | >50% | >50% | Destabilizes inhibitor site |

| E154S | ~100% (Completely Resistant) | Data Not Provided | Direct interference with binding |

Q4: What are the most critical steps for validating that an engineered mutation truly confers feedback resistance rather than causing nonspecific effects?

A4: Essential validation steps include:

- Steady-State Kinetics: Determine Km, kcat, and Ki values for wild-type and mutants across multiple inhibitor concentrations [43] [40].

- Thermal Shift Assays: Verify mutations do not significantly destabilize protein fold [40].

- X-ray Crystallography or Cryo-EM: Confirm structural changes are localized to allosteric site without disrupting catalytic architecture [40].

- In Vivo Testing: Demonstrate improved product titers in microbial hosts under controlled fermentation conditions [42].

Q5: Can feedback resistance be engineered into any enzyme, and what are the potential trade-offs?

A5: While theoretical possible for most allosteric enzymes, success depends on detailed structural knowledge of allosteric and catalytic sites [43]. Potential trade-offs include:

- Reduced Catalytic Efficiency: Mutations may negatively impact kcat or substrate binding [40].

- Decreased Protein Stability: Allosteric sites often contribute to structural integrity; mutations can destabilize fold [40].

- Metabolic Imbalance: Unregulated enzymes may deplete cellular precursors or energy, hindering host growth [43].

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: In Vitro Screening for Feedback-Resistant Enzyme Variants

Objective: Identify feedback-resistant mutants from a library of enzyme variants using a high-throughput activity assay [40] [42].

Materials:

- Purified enzyme variants (wild-type control and mutants)

- Substrate solution (concentration ≥ 10×Km)

- Inhibitor stock (target amino acid, e.g., 100 mM L-tyrosine)

- Reaction buffer (optimal pH and ionic strength)

- Stopping solution (compatible with detection method)

- Microtiter plates (96-well or 384-well)

- Plate reader or HPLC system for quantification

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In separate wells, prepare two reaction mixtures for each variant:

- Condition A (Uninhibited): 90 µL substrate solution + 10 µL enzyme

- Condition B (Inhibited): 85 µL substrate solution + 5 µL inhibitor stock + 10 µL enzyme

- Incubation: Incubate at process temperature (e.g., 30-37°C) for precisely 10 minutes.

- Reaction Termination: Add 100 µL stopping solution to each well.

- Product Quantification: Measure product formation using plate reader (if chromogenic/fluorogenic) or HPLC for accurate quantification [42].

- Data Analysis: Calculate residual activity for each variant: (ActivityCondition B / ActivityCondition A) × 100%. Select variants showing >50% residual activity at inhibitor concentrations that fully inhibit wild-type.

Protocol 2: Computational Workflow for Predicting Resistance Mutations

Objective: Use homology modeling and free energy calculations to predict stabilizing mutations that disrupt allosteric binding [40].

Materials:

- Target enzyme sequence (FASTA format)

- Template structures (from PDB) with high sequence identity

- Homology modeling software (e.g., MODELLER, SWISS-MODEL)

- Molecular dynamics software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER)

- Folding energy calculation tools (FoldX, Rosetta)

Procedure:

- Homology Modeling:

- Identify suitable template structures (≥30% sequence identity) from PDB.

- Generate 3D model of target enzyme using comparative modeling.

- Validate model geometry using Ramachandran plots and clash scores.

- Allosteric Site Identification:

- Superpose target model with template structures complexed with inhibitors.

- Identify residues within 5Ã… of bound inhibitor as potential mutation targets.

- Mutation Design: