Measuring Success: Key Efficiency Metrics and Optimization Strategies for Biosynthetic Pathways

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of quantifying and enhancing efficiency in biosynthetic pathways for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Measuring Success: Key Efficiency Metrics and Optimization Strategies for Biosynthetic Pathways

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of quantifying and enhancing efficiency in biosynthetic pathways for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore foundational metrics like titer, yield, and productivity, then delve into advanced computational methodologies for pathway design and optimization. The article provides practical troubleshooting frameworks for overcoming metabolic bottlenecks and presents rigorous validation approaches through comparative omics analysis. By synthesizing recent advances in lifespan engineering, computational workflow integration, and AI-driven pathway navigation, this resource offers a strategic roadmap for developing high-performance microbial cell factories capable of economically viable production of valuable plant natural products and pharmaceuticals.

Defining Biosynthetic Efficiency: Core Metrics and Fundamental Barriers

In the field of synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, the successful scaling of microbial production from laboratory experiments to industrial manufacturing depends on the rigorous optimization of three fundamental efficiency indicators: titer, yield, and productivity. Collectively known as the TRY metrics, these parameters provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating the technical and economic viability of biosynthetic pathways [1] [2]. Titer, measured typically in grams per liter (g/L), represents the final concentration of the target compound achieved in a fermentation broth, directly influencing downstream processing costs. Yield, expressed as grams of product per gram of substrate (g/g), quantifies the conversion efficiency of raw materials, determining resource utilization and material costs. Productivity, measured as grams per liter per hour (g/L/h), reflects the volumetric production rate, which dictates the reactor size and capital investment required for a given output [1] [3] [2].

The critical importance of these metrics extends beyond technical performance to encompass fundamental economic considerations. As noted in research on strain design strategies, "the economic viability of a bioprocess is commonly evaluated by its product yield, titer, and productivity" [3]. These parameters respectively reflect the downstream processing costs, reactor size determinants, and raw material utilization efficiency that collectively determine commercial feasibility [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of TRY metrics across diverse biosynthetic pathways, experimental methodologies for their optimization, and visual frameworks for understanding their interconnected relationships in pathway engineering.

Comparative Performance of TRY Metrics Across Biosynthetic Pathways

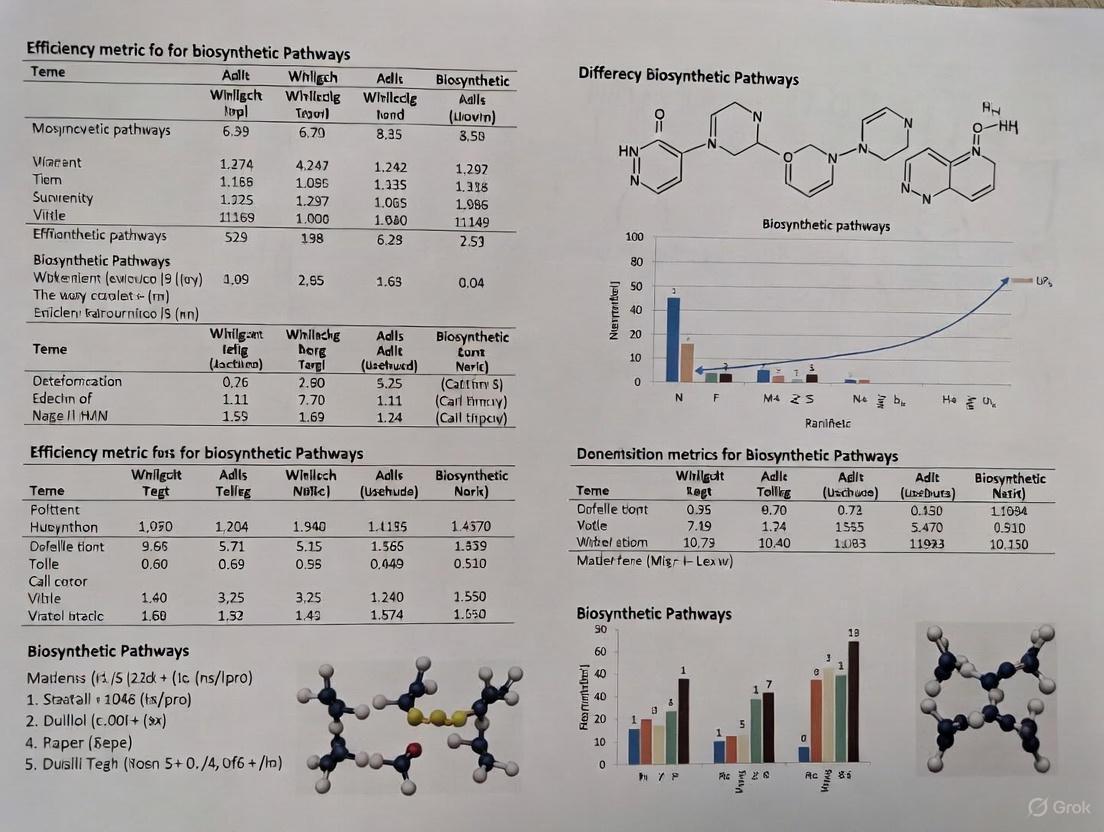

The TRY metrics vary significantly across different microbial hosts and target compounds, reflecting the unique metabolic challenges and engineering solutions for each system. The following table summarizes reported performance data for several biologically-produced compounds, illustrating the range of achievable efficiencies.

Table 1: Comparative TRY Metrics for Selected Biological Productions

| Compound | Host Organism | Titer (g/L) | Yield (g/g) | Productivity (g/L/h) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | E. coli W3110 | 22.58 | - | - | [4] |

| Psilocybin | E. coli (de novo) | 2.00 | - | - | [5] |

| Psilocybin | S. cerevisiae | 0.627 | - | - | [5] |

| Naringenin | E. coli M-PAR-121 | 0.765 | - | - | [6] |

| Naringenin | S. cerevisiae | 1.129 | - | - | [6] |

| Indigoidine | P. putida KT2440 | 25.6 | 0.33 (g/g glucose) | 0.22 | [2] |

The data reveals substantial variability in optimization performance across different host systems. For instance, the highest reported naringenin titer in S. cerevisiae (1.129 g/L) significantly exceeds that in E. coli (0.765 g/L), highlighting host-specific metabolic capabilities [6]. Similarly, psilocybin production has been more successful in S. cerevisiae (627 mg/L in fed-batch) compared to early E. coli systems (27.7 mg/L), though recent engineering advances in E. coli have dramatically improved performance to 2.00 g/L [5]. These differences underscore the importance of host selection and pathway optimization in achieving competitive TRY metrics.

The MCF2Chem knowledge base, a manually curated resource containing 8,888 production records for 1,231 compounds produced by 590 microbial cell factories, provides broader context for these performance benchmarks [7]. Statistical analysis of this database shows that bacteria account for approximately 60% of microbial chassis used in production, with Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Yarrowia lipolytica, and Corynebacterium glutamicum collectively synthesizing 78% of reported chemical compounds [7]. This distribution reflects the established engineering tools and metabolic capabilities of these preferred platforms.

Experimental Protocols for TRY Metric Optimization

Systematic Pathway Optimization for Naringenin Production

The stepwise optimization of naringenin production in E. coli demonstrates a systematic methodology for enhancing TRY metrics [6]. The research began with the evaluation of tyrosine ammonia-lyase (TAL) genes from different sources expressed in three distinct E. coli strains to maximize p-coumaric acid production (achieving 2.54 g/L in the tyrosine-overproducing M-PAR-121 strain with TAL from Flavobacterium johnsoniae). The optimal strain was then used to express combinations of 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL) and chalcone synthase (CHS) genes from various organisms, resulting in 560.2 mg/L of naringenin chalcone with the FjTAL, At4CL (Arabidopsis thaliana), and CmCHS (Cucurbita maxima) combination. Finally, different chalcone isomerase (CHI) genes were validated, with CHI from Medicago sativa yielding the highest naringenin production of 765.9 mg/L [6]. This sequential approach isolates variables at each pathway step, enabling identification of the optimal enzyme combination.

Dynamic Strain Scanning Optimization (DySScO) Strategy

For more sophisticated TRY optimization, the Dynamic Strain Scanning Optimization (DySScO) strategy integrates dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA) with existing strain design algorithms to balance yield, titer, and productivity [3]. This computational framework consists of three phases:

- Scanning Phase: Identification of the production envelope (Pareto frontier in product flux vs. biomass flux) and creation of hypothetical flux distributions along this envelope, followed by dFBA simulations of these distributions in bioreactor environments.

- Design Phase: Application of strain design algorithms (such as OptKnock or GDLS) to find high-product-yield strains within the optimal growth rate range identified in the scanning phase.

- Selection Phase: Dynamic simulation of designed strains using dFBA, performance evaluation using a consolidated performance metric (CSP) that weights yield, titer, and productivity, and selection of the optimal strain design [3].

This approach addresses a critical limitation of metabolic engineering strategies that focus solely on cellular metabolism without considering bioprocess dynamics, thereby enabling simultaneous optimization of all three TRY metrics [3].

Growth-Coupled Production Using Minimal Cut Sets

The application of Minimal Cut Set (MCS) analysis represents an advanced strategy for TRY optimization by genetically rewiring metabolism to couple product synthesis with growth [2]. In one demonstration, researchers computed MCS solution-sets for indigoidine production in Pseudomonas putida KT2440, identifying one experimentally feasible solution requiring 14 simultaneous reaction interventions from 63 possible solutions. Implementing these 14 gene knockdowns using multiplex-CRISPRi shifted production from stationary to exponential phase, achieving 25.6 g/L titer, 0.22 g/L/h productivity, and approximately 50% of the maximum theoretical yield (0.33 g indigoidine/g glucose) [2]. This growth-coupled approach ensures continuous production during active biomass accumulation, significantly enhancing volumetric productivity.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TRY Optimization

| Reagent/Technique | Function in TRY Optimization | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex CRISPRi | Enables simultaneous knockdown of multiple metabolic reactions | Implementing 14 reaction interventions in P. putida for growth-coupled indigoidine production [2] |

| dFBA (Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis) | Models metabolic network within bioreactor dynamics | Predicting titer and productivity in DySScO strategy [3] |

| Minimal Cut Set (MCS) Algorithm | Identifies minimal reaction sets whose elimination couples production to growth | Designing P. putida strain with obligatory indigoidine production during growth [2] |

| Tyrosine-overproducing Strains (E. coli M-PAR-121) | Provides enhanced precursor supply for pathway optimization | Increasing p-coumaric acid production for naringenin synthesis [6] |

| Two-stage pH Fermentation Strategy | Separates growth and production phases, reduces product degradation | Enhancing dopamine yield in E. coli (22.58 g/L) [4] |

Visualization of TRY Optimization Workflows and Metabolic Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental workflows and metabolic relationships for TRY optimization, providing visual guidance for implementing these strategies.

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for systematic TRY metric optimization in biosynthetic pathway engineering, illustrating the progression from in silico design to strain engineering and bioprocess optimization.

Diagram 2: Metabolic pathway for naringenin production in engineered E. coli, highlighting both native metabolism (gray) and heterologous enzymes (blue) introduced for biosynthesis [6].

The comparative analysis of TRY metrics across diverse biosynthetic pathways reveals several strategic implications for researchers and drug development professionals. First, the selection of microbial host should be guided not only by historical precedent but by systematic evaluation of the specific metabolic demands of the target pathway, as demonstrated by the superior naringenin production in S. cerevisiae versus E. coli [6]. Second, the integration of computational design tools like MCS analysis and DySScO with advanced gene editing technologies enables more predictable and effective pathway optimization [3] [2]. Third, the development of specialized fermentation strategies, such as two-stage pH control or cofactor feeding, can dramatically enhance TRY metrics even in extensively engineered strains [4].

As synthetic biology continues to expand the range of complex molecules accessible through microbial production, the strategic optimization of titer, yield, and productivity will remain essential for translating laboratory innovations into commercially viable bioprocesses. The frameworks, data, and methodologies presented in this guide provide a foundation for researchers to systematically approach this optimization challenge, balancing the inherent trade-offs between these critical metrics while advancing the frontier of sustainable chemical production.

Within industrial biotechnology, prolonged fermentation processes are critical for producing high-value biomolecules, from therapeutic proteins to alternative food ingredients. However, the productivity of these bioprocesses is intrinsically limited by the physiological decline of microbial and cellular workhorses. This review examines the critical limitations imposed by cellular aging and metabolic stress on prolonged fermentation, framing these challenges within the broader thesis of evaluating efficiency metrics for biosynthetic pathways. As living catalysts, the metabolic vitality of production organisms directly dictates the economic viability and scalability of fermentation-based manufacturing. A comparative analysis of experimental data reveals how aging-associated decline in metabolic function creates bottlenecks, providing a framework for researchers to quantify and overcome these barriers in pathway engineering and bioprocess optimization.

Cellular Hallmarks of Aging in Production Organisms

During extended fermentation, production organisms exhibit molecular and cellular changes that mirror hallmark aging processes, directly impacting metabolic output and culture longevity. These processes are conserved across model systems from yeast to mammalian cells.

- Genomic Instability and DNA Damage: Accumulation of DNA damage during prolonged culture activates DNA damage response (DDR) pathways, diverting cellular resources away from production and toward repair mechanisms. In yeast models, this damage is exacerbated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated as metabolic byproducts, particularly under industrial fermentation conditions [8] [9].

- Metabolic Dysregulation: Aging cells experience mitochondrial dysfunction and declining energy production. Integrated metabolic models of aging mouse gut microbiomes reveal a pronounced reduction in metabolic activity accompanied by downregulation of essential pathways in nucleotide metabolism critical for maintaining cellular replication and homeostasis during sustained fermentation [10].

- Loss of Proteostasis: With replicative age, cells progressively lose the ability to maintain protein homeostasis, leading to accumulation of misfolded proteins. This is particularly detrimental in precision fermentation where microbial hosts are engineered to overexpress recombinant proteins, creating substantial proteostatic stress that can trigger stress responses and reduce yields [9].

- Cellular Senescence: Production organisms can enter a state of irreversible growth arrest while remaining metabolically active but with altered secretion profiles. Senescent cells exhibit the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), releasing inflammatory cytokines and proteases in mammalian systems or altering metabolite secretion in microbial systems, which can negatively impact product quality and culture homogeneity [9].

Table 1: Hallmarks of Cellular Aging in Fermentation Systems

| Aging Hallmark | Impact on Fermentation Efficiency | Experimental Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Instability | Reduced genetic fidelity, mutation accumulation | γ-H2AX foci, COMET assay [8] |

| Metabolic Dysregulation | Declining ATP production, reduced biosynthesis | NAD+/NADH ratio, ATP assays [10] |

| Loss of Proteostasis | Recombinant protein aggregation, reduced yields | Heat shock protein levels, aggregation assays [9] |

| Cellular Senescence | Culture growth arrest, altered product profile | β-galactosidase staining, SASP analysis [9] |

| Mitochondrial Dysfunction | Increased ROS, oxidative stress damage | ROS staining, mitochondrial membrane potential [8] |

Comparative Analysis of Aging Across Model Systems

Different production platforms exhibit distinct aging dynamics under industrial fermentation conditions. Understanding these system-specific aging trajectories is essential for selecting appropriate production hosts for long-duration bioprocesses.

Microbial Systems (Yeast/Bacteria)

The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae serves as a fundamental eukaryotic model for aging research due to its short lifespan and well-characterized genetics. Yeast aging studies have identified clear relationships between intracellular metabolites and aging under fermentation conditions. Specifically, trehalose levels increase with aging and under calorie restriction, indicating activation of protective responses against cellular stress during fermentation [11]. NMR-based metabolomics reveals that both calorie restriction and quercetin treatment significantly increase intracellular proline levels, which regulate mitochondrial function and decline with age, suggesting shared metabolic pathways for longevity promotion in fermentation environments [11].

Mammalian Cell Systems

Mammalian cells used in advanced fermentation applications exhibit more complex aging phenotypes. Primary cells have a finite replicative capacity—the Hayflick limit—before entering replicative senescence, fundamentally limiting their utility in prolonged bioprocesses [9]. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) offer potential solutions but still retain aging signatures from donor cells. Research demonstrates that neurons from aged donors retain critical features of aging including reduced mitochondrial activity and increased ROS levels, which would directly impact their performance as production hosts in extended fermentations [9].

Table 2: System-Specific Aging Characteristics in Fermentation

| Production System | Key Aging Markers | Impact on Prolonged Fermentation |

|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae (Yeast) | Trehalose accumulation, proline decline, ROS increase [11] | Reduced ethanol tolerance, decreased recombinant protein yield |

| L. plantarum (Lactic Acid Bacteria) | Acid stress response, redox imbalance [12] | Reduced viability, altered metabolite profiles in fermented foods |

| Mammalian Cell Culture | Telomere attrition, SASP secretion, epigenetic alterations [9] | Growth arrest, altered product glycosylation, batch inconsistency |

| Filamentous Fungi | Hyphal fragmentation, autolysis [13] | Reduced enzyme secretion, morphology changes |

Metabolic Stress Pathways and Experimental Assessment

Metabolic stress during fermentation arises from intrinsic and extrinsic factors that collectively impact cellular aging and biosynthetic capacity. The interplay between these stressors and aging pathways creates a self-reinforcing cycle that accelerates functional decline in production organisms.

Diagram 1: Metabolic Stress Pathways in Prolonged Fermentation. Intrinsic and extrinsic stressors converge on core cellular damage pathways that ultimately impact fermentation performance.

Experimental Methodologies for Quantifying Aging and Stress

Research into fermentation-associated aging employs standardized assays to quantify both chronological and replicative lifespan under industrial conditions:

Chronological Lifespan (CLS) Assay: Measures the survival time of non-dividing cells in stationary phase, relevant for batch fermentation processes. Implementation involves spot assays where yeast cells are cultured in YPD media under different glucose concentrations (2.0%, 0.5%, 0.2% for calorie restriction studies), transferred to fresh media, and viability determined through serial dilution spotting on agar plates followed by incubation and colony counting [11].

Replicative Lifespan (RLS) Assay: Quantifies the number of daughter cells produced by a mother cell before senescence, critical for continuous fermentation systems. This typically uses biotin-streptavidin labeling or mother cell enrichment systems with micromanipulation to count progeny [11].

Metabolomic Profiling: ¹H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-based metabolomics enables comprehensive quantification of intracellular metabolites during aging. Sample preparation involves adjusting cell densities to OD₆₀₀=20, washing pellets with phosphate buffer, quenching in liquid nitrogen, and metabolite extraction before analysis to identify aging signatures like trehalose and proline fluctuations [11].

Integrated Metabolic Modeling: Constraint-based reconstruction of metabolic networks from multi-omics data (metagenomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics) predicts metabolic fluxes and host-microbiome interactions during aging. This approach has revealed aging-associated declines in metabolic activity and reduced beneficial interactions in mouse gut microbiome studies, with applications to fermentation systems [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Fermentation-Associated Aging

| Reagent/Category | Function in Aging Research | Specific Examples & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Lifespan Assay Kits | Quantify replicative and chronological aging | Yeast CLS spot assay components [11] |

| Metabolic Probes | Detect mitochondrial function and ROS | H2DCFDA for ROS, TMRE for membrane potential [8] |

| Senescence Markers | Identify senescent cells in culture | β-galactosidase detection kits [9] |

| NMR Metabolomics | Comprehensive metabolite profiling | ¹H NMR instrumentation and protocols [11] |

| DNA Damage Assays | Quantify genomic instability | γ-H2AX antibodies, COMET assay kits [8] |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Tools | Predict metabolic flux changes | gapseq for metabolic network reconstruction [10] |

Cellular aging and metabolic stress represent fundamental bottlenecks in prolonged fermentation processes, directly impacting key efficiency metrics for biosynthetic pathways. The experimental data comparative analysis reveals that strategies targeting metabolic resilience—such as calorie restriction mimetics, antioxidant treatments, and proline supplementation—show promise in extending the productive lifespan of fermentation hosts. Future pathway engineering efforts should prioritize stability metrics alongside productivity, incorporating age-resilience as a design parameter in synthetic biology approaches. By quantifying and addressing these critical limitations, researchers can develop next-generation production systems that maintain metabolic vitality throughout prolonged fermentation cycles, ultimately enhancing the sustainability and economic viability of industrial biotechnology.

Comparative Analysis of Native vs. Heterologous Pathway Performance Metrics

In the development of microbial cell factories, a fundamental strategic choice involves utilizing a host's innate, native metabolic pathways versus introducing engineered, heterologous pathways from other organisms. This decision critically influences the overall efficiency, yield, and economic viability of bioproduction processes for chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and enzymes. Native pathways are integrated into the host's existing regulatory and metabolic networks, whereas heterologous pathways often provide a direct and optimized route to the target compound but require careful balancing with host physiology [14]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, underpinned by recent experimental data and performance metrics, to inform researchers and scientists in the field of drug development and metabolic engineering.

Performance Metrics Comparison

The performance of biosynthetic pathways is quantitatively assessed using three key metrics: titer (the concentration of the product, typically in mg/L or g/L), yield (the amount of product formed per unit of substrate, often in mol/mol or g/g), and productivity (the rate of product formation, in mg/L/h or g/L/h) [15]. The following tables summarize these metrics for various products from recent studies, comparing native and heterologous production routes.

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Metabolite Production in Engineered Strains

| Target Product | Host Organism | Pathway Type | Key Engineering Strategy | Max Titer (mg/L) | Yield (mol/mol glucose) | Productivity (mg/L/h) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naringenin | E. coli | Heterologous | Step-wise enzyme screening & host engineering (M-PAR-121) | 765.9 (Shake-flask) | - | - | [6] |

| Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) | Bacillus subtilis | Native & Heterologous | DXP-independent pathway & medium optimization | 174.6 (Fed-batch) | - | - | [16] |

| Indigoidine | E. coli BL21(DE3) | Heterologous | NRPS/PPTase screening & membrane engineering | 26,710 (Fed-batch) | - | - | [17] |

| L-Lysine | S. cerevisiae | Native (L-2-aminoadipate) | - | - | 0.8571 (YT) | - | [15] |

| L-Lysine | E. coli | Native (Diaminopimelate) | - | - | 0.7985 (YT) | - | [15] |

| L-Lysine | C. glutamicum | Native (Diaminopimelate) | - | - | 0.8098 (YT) | - | [15] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Heterologous Protein Production in Aspergillus niger [18]

| Target Protein | Origin | Expression Host | Engineering Strategy | Max Titer (mg/L) | Enzyme Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (AnGoxM) | Aspergillus niger (Homologous) | A. niger AnN2 | TeGlaA copy reduction & PepA disruption | 416.8 | ~1276-1328 U/mL |

| Pectate Lyase (MtPlyA) | Myceliophthora thermophila | A. niger AnN2 | Site-specific integration & Cvc2 overexpression | 130.7 (+18%) | ~1627-2106 U/mL |

| Triose Phosphate Isomerase (TPI) | Bacterial | A. niger AnN2 | Site-specific integration | 110.8 | ~1751-1907 U/mg |

| Immunomodulatory Protein (LZ8) | Ganoderma lucidum | A. niger AnN2 | Site-specific integration | 163.3 | - |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: De Novo Naringenin Production in E. coli

This protocol outlines the step-wise optimization of a heterologous pathway in E. coli for the high-titer production of naringenin, a plant polyphenol [6].

- Strain Construction: The heterologous pathway was constructed in the tyrosine-overproducing E. coli strain M-PAR-121. Genes were cloned into plasmid vectors (e.g., pRSFDuet-1, pCDFDuet-1) under inducible T7 promoters.

- Step-wise Pathway Validation:

- TAL Screening: Two tyrosine ammonia-lyase (TAL) genes from different sources were expressed in three E. coli strains (BL21(DE3), K-12 MG1655(DE3), M-PAR-121). Production of the intermediate p-coumaric acid was measured to select the best TAL (from Flavobacterium johnsoniae) and host (M-PAR-121) combination.

- 4CL and CHS Screening: The best TAL was combined with different 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL) and chalcone synthase (CHS) genes. The combination of FjTAL, At4CL (Arabidopsis thaliana), and CmCHS (Cucurbita maxima) yielded the highest naringenin chalcone.

- CHI Screening: Different chalcone isomerase (CHI) genes were tested. CHI from Medicago sativa (MsCHI) was identified as the most effective for the final conversion to naringenin.

- Cultivation and Production: Production experiments were conducted in shake flasks. After initial growth, gene expression was induced, and cultures were supplemented with the carbon source. Naringenin production was quantified over time using HPLC after removing cell biomass via centrifugation.

Protocol 2: Platform for Heterologous Protein Expression in Aspergillus niger

This protocol describes the creation of a chassis strain and a modular platform for high-yield heterologous protein expression in the industrial fungus A. niger [18].

- Chassis Strain Development: The industrial glucoamylase hyperproducer A. niger AnN1 was engineered using a CRISPR/Cas9-assisted marker recycling system.

- Gene Copy Reduction: Thirteen of the 20 native tandem copies of the TeGlaA gene were deleted to reduce background protein secretion.

- Protease Disruption: The major extracellular protease gene PepA was disrupted to minimize degradation of the target heterologous protein. The resulting strain was named AnN2.

- Modular Protein Expression:

- Vector Construction: A donor DNA plasmid was designed with the native AAmy promoter and AnGlaA terminator as homologous arms for integration.

- Site-Specific Integration: Target genes (e.g., MtPlyA, LZ8) were integrated into the high-expression loci previously occupied by the deleted TeGlaA copies in the AnN2 chassis strain via CRISPR/Cas9.

- Secretory Pathway Engineering: To further enhance yield, the COPI vesicle trafficking component gene Cvc2 was overexpressed in strains expressing target proteins like MtPlyA.

- Cultivation and Analysis: Transformants were cultivated in shake flasks for 48-72 hours. Extracellular proteins in the culture supernatant were analyzed. Target protein titer was quantified, and enzyme activity was measured using specific activity assays.

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow for heterologous pathway optimization and the specific engineered pathways discussed in this guide.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for the step-wise optimization of a heterologous biosynthetic pathway in a microbial host, as demonstrated for naringenin production [6].

Figure 2: The heterologous pathway for de novo naringenin production in E. coli. Enzyme abbreviations and their optimal sources identified in the study are: TAL (Tyrosine ammonia-lyase), 4CL (4-coumarate-CoA ligase), CHS (Chalcone synthase), CHI (Chalcone isomerase) [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section details key reagents, strains, and molecular tools frequently employed in the construction and optimization of heterologous pathways.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Pathway Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Model Host Organisms | Microbial chassis for pathway integration and testing. | E. coli BL21(DE3), B. subtilis, S. cerevisiae, A. niger [15] [18] |

| Specialized Engineered Strains | Hosts with enhanced precursor supply for specific pathways. | E. coli M-PAR-121 (Tyrosine overproducer) [6] |

| Expression Vectors | Plasmids for cloning and expressing heterologous genes. | pRSFDuet-1, pCDFDuet-1, pACYCDuet-1 [6] |

| Genome Editing Systems | Tools for precise genomic modifications (deletions, integrations). | CRISPR/Cas9 system for A. niger [18] |

| Enzyme / Gene Libraries | Diverse sources of heterologous genes for pathway screening. | TAL, 4CL, CHS, CHI genes from various plants and microbes [6] |

| Computational Pathway Tools | Algorithms for in silico pathway design and host selection. | SubNetX for pathway extraction and ranking [19] |

| Genome-Scale Models (GEMs) | Metabolic models for predicting yield and flux analysis. | GEMs of E. coli, S. cerevisiae, etc., for calculating YT and YA [15] |

Within metabolic engineering and biosynthetic pathway research, the selection of an appropriate microbial host is a critical determinant of success. The model organisms Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae represent the two most extensively utilized platforms for the production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and commodity chemicals. Framed within a broader thesis on efficiency metrics for biosynthetic pathways, this guide provides an objective comparison of these organisms' inherent metabolic capabilities, supported by experimental data. Understanding their core physiological and genetic differences enables researchers to make informed, rational decisions for host selection to maximize titer, yield, and productivity for a given target compound [20].

Core Physiological and Metabolic Comparison

The fundamental divergence between the prokaryotic E. coli and the eukaryotic S. cerevisiae extends beyond cellular structure to their core metabolism, regulatory mechanisms, and tolerance to process conditions. These inherent characteristics directly influence their suitability for specific biosynthetic pathways.

Table 1: Core Physiological and Metabolic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Escherichia coli | Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

|---|---|---|

| Organism Type | Prokaryote (Bacterium) | Eukaryote (Yeast) |

| Metabolic Pathway | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) pathway [21] | Mevalonate (MVA) pathway [21] |

| IPP Precursors | Pyruvate & Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate [21] | Acetyl-CoA [21] |

| Theoretical Max IPP Yield (Glucose) | Higher potential yield from glucose [21] | Lower potential yield from glucose due to carbon loss in Acetyl-CoA formation [21] |

| Preferred Carbon Sources | Wide range, including glycerol [22] | Sugars (e.g., glucose, sucrose) |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Can be engineered for high furfural tolerance [23] | Naturally high tolerance to low pH and osmotic pressure [21] |

| Post-Translational Modifications | Limited; inability to perform eukaryotic PTMs [24] | Extensive; capable of complex PTMs similar to higher eukaryotes [25] [24] |

| Cofactor Regeneration | Can be engineered for balanced NADPH/NADH usage [26] | Native strong tendency to regenerate NAD+ for anaerobic growth [27] |

| Subcellular Organization | Cytoplasmic production; can store hydrophobic products in enlarged membranes [26] | Compartmentalization; allows for harnessing organelles [21] |

| GRAS Status | Not classified as GRAS | Generally Regarded As Safe (GRAS) [27] [25] |

Quantitative Performance in Key Pathways

Direct comparative studies and organism-specific optimizations reveal performance disparities in the production of valuable compounds. The data below, drawn from peer-reviewed literature, highlights achievable titers and yields.

Table 2: Representative Production Metrics for Selected Compounds

| Product | Host | Titer | Yield | Key Engineering Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Squalene | E. coli | 1267 mg/L [26] | N/R | Redox-balanced HMGR, membrane lipid remodeling, in situ extraction [26] |

| Lycopene | E. coli | N/R | N/R | Systematic computational search & gene deletion using MOMA [28] |

| Ethanol (from Crude Glycerol) | E. coli | ~2.5 g/L [22] | N/R | Microaerobic fermentation conditions [22] |

| S. cerevisiae | ~4.5 g/L [22] | N/R | Use of isolated or evolved strains [22] | |

| L-Threonine | E. coli | N/R | N/R | Model-driven parametric sensitivity analysis of key enzymes [28] |

| Artemisinic Acid | S. cerevisiae | 25 g/L [25] | N/R | Full pathway reconstruction & strain optimization [25] |

| Vinblastine | S. cerevisiae | N/R | N/R | Extensive genomic engineering (56 edits) [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Analysis and Engineering

In Silico Profiling of Terpenoid Production Potential

Objective: To computationally compare the theoretical potential of E. coli and S. cerevisiae for producing isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP), the universal terpenoid precursor [21].

Methodology:

- Network Reconstruction: Genome-scale metabolic models for both organisms are constructed. The model for E. coli typically incorporates 65 reactions and 50 metabolites, while the model for S. cerevisiae includes 69 reactions and 60 metabolites, focusing on central carbon metabolism [21].

- Stoichiometric Analysis: The carbon, energy, and redox stoichiometries of the native DXP (E. coli) and MVA (S. cerevisiae) pathways are analyzed independently of the host network.

- Elementary Mode Analysis (EMA): EMA is used to calculate all feasible steady-state flux distributions through the metabolic network. This identifies the theoretical maximum yield of IPP on a given carbon source (e.g., glucose, xylose, glycerol) without requiring kinetic parameters [21].

- Identification of Engineering Targets:

- Overexpression Targets: EMs are analyzed to pinpoint reactions in central metabolism whose overexpression could alleviate energy and redox deficiencies that limit terpenoid yield.

- Knockout Strategies: The concept of Constrained Minimal Cut Sets (cMCSs) is applied. This computational algorithm identifies a minimal set of gene deletions that obligately couple cell growth to a high yield of the desired product, forcing the organism to become a high-yielding factory [21].

Systems Metabolic Engineering for Squalene Production in E. coli

Objective: To enhance the production of the hydrophobic triterpene squalene in E. coli by addressing pathway efficiency and product storage [26].

Methodology:

- Cofactor Engineering:

- A hybrid 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGR) system is developed by combining NADPH-dependent and NADH-preferred enzymes.

- This strategy balances the intracellular NADPH/NADH ratio, leading to increased precursor flux and a reported squalene titer of 852.06 mg/L [26].

- Membrane & Storage Engineering:

- To address the limited storage capacity for hydrophobic products, the membrane morphology is engineered.

- Overexpression of genes dgs, murG, and plsC generates lipid-enriched, elongated cells, creating more internal storage space. This intervention boosts squalene production to 970.86 mg/L [26].

- Process Optimization:

- A delayed induction strategy is implemented to separate the growth and production phases.

- An in situ recovery system using a 10% dodecane overlay is applied to continuously extract squalene from the culture, mitigating potential product toxicity. This final optimization achieves a final titer of 1267.01 mg/L in a 3 L bioreactor [26].

Metabolic Pathway Diagrams

The diagram illustrates the fundamental metabolic routes for producing the universal terpenoid precursors, IPP and DMAPP, in E. coli and S. cerevisiae. The DXP pathway in E. coli starts from the glycolysis intermediates glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) and pyruvate (PYR). In contrast, the Mevalonate (MVA) pathway in S. cerevisiae initiates from acetyl-CoA (AcCoA). This divergence in precursor origin is a critical factor in the theoretical yield calculations, with the DXP pathway possessing a higher potential carbon yield from glucose [21].

This workflow provides a rational framework for selecting between E. coli and S. cerevisiae based on project-specific requirements and the metabolic characteristics of each organism. Key decision points include the complexity of the target molecule, the theoretical yield of the biosynthetic pathway, and the intended application of the final product [25] [21] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Enables precise genome editing, knockout, and insertion of heterologous pathways. [23] [25] | Used in S. cerevisiae for the complex engineering required to produce vinblastine (56 edits). [25] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | In silico models (e.g., iAF1260 for E. coli) that predict organism behavior and identify engineering targets. [28] | Used in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to predict gene knockout strategies for improving lycopene production. [28] |

| Constrained Minimal Cut Sets (cMCSs) | A computational algorithm to identify minimal gene knockouts that couple growth to high product yield. [21] | Identified knockout strategies for E. coli and S. cerevisiae to create IPP-overproducing strains. [21] |

| Heterologous Pathways | Introduction of non-native metabolic routes into a host chassis. | Introduction of the MVA pathway into E. coli to enhance terpenoid production, circumventing native regulation. [21] |

| Inducible Promoters (e.g., GAL, CUP1) | Tightly regulated promoters that control the timing and level of gene expression. [24] | Used in S. cerevisiae to control the expression of toxic proteins or to separate growth and production phases. [24] |

| In Situ Extraction Solvents (e.g., Dodecane) | An overlay solvent that continuously extracts hydrophobic products from the fermentation broth. [26] | Used in E. coli squalene production to reduce product toxicity and inhibition, boosting final titer. [26] |

A fundamental challenge in metabolic engineering is rewiring a microbe's core metabolism to channel carbon and energy toward a desired product, a process that often creates a metabolic burden and trade-off with cell growth [29]. The optimization of central precursor availability is therefore paramount. Platform strains with engineered central carbon metabolism (CCM)—encompassing glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)—provide the foundational metabolic driving force, or flux, for diverse biosynthetic pathways [30]. This guide objectively compares the performance of major platform strain engineering strategies, providing the experimental data and methodologies essential for selecting the optimal chassis for a given biosynthetic goal.

Comparative Analysis of Platform Strain Performance

Different engineering strategies manipulate CCM to enhance the supply of key precursor metabolites. The table below summarizes the performance outcomes of several major approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Platform Strain Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Metabolic Flux

| Engineering Strategy | Key Precursor Enhanced | Chassis Organism | Target Product | Reported Yield/Improvement | Key Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterologous PHK Pathway [30] | Acetyl-CoA, E4P | S. cerevisiae | Fatty Acid Ethyl Esters | 5100 ± 509 g/CDW (cell dry weight) [30] | Overexpression of Adh2, Ald6, ACS; introduction of PHK pathway. |

| Heterologous PHK Pathway [30] | Acetyl-CoA, E4P | S. cerevisiae | p-Hydroxycinnamic Acid | 12.5 g/L (154.9 mg/g glucose yield) [30] | Promoter optimization & dynamic regulation post-PHK introduction. |

| Heterologous PDH Pathway [30] | Acetyl-CoA | S. cerevisiae | General Acetyl-CoA | ~2-fold increase in acetyl-CoA [30] | Expression of NADP+-dependent E. coli PDH pathway. |

| Dynamic Genetic Circuits [29] | Varies based on pathway | E. coli | Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) | High-level production from glycerol [29] | Dynamic metabolic control circuit to balance growth and production. |

| Sensor-Driven Evolution [31] | Varies based on pathway | E. coli | Naringenin & Glucaric Acid | 36-fold and 22-fold increase, respectively [31] | Biosensor-coupled selection; 4 rounds of evolution. |

| Flux-Enhanced Cell Extracts [32] | Shikimate Pathway Precursors | E. coli Extract | Muconic Acid | 4.5 mg/L (enabled detection) [32] | Cell-free prototyping using extract from rewired strain. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Engineering Methodologies

Protocol: Engineering the Heterologous Phosphoketolase (PHK) Pathway

The introduction of the PHK pathway is a widely validated strategy to enhance acetyl-CoA and E4P supply [30].

- Gene Identification and Cloning: Identify and codon-optimize genes for phosphoketolase (PK) and phosphotransacetylase (PTA) from donor organisms (e.g., Aspergillus nidulans).

- Vector Construction: Clone the PK and PTA genes into an appropriate expression vector under the control of strong, constitutive, or inducible promoters.

- Strain Transformation: Introduce the constructed plasmid into the chassis organism (e.g., S. cerevisiae).

- Pathway Validation: Confirm functional enzyme expression via proteomics and measure the impact on central metabolism by tracking changes in intracellular metabolite pools (e.g., acetyl-CoA, E4P) using LC-MS.

- Host Strain Optimization (Optional): To further enhance flux, knock out competing pathways (e.g., phosphofructokinase in Yarrowia lipolytica to redirect glycolytic flux) or overexpress downstream pathway genes [30].

- Fermentation and Analysis: Perform fed-batch fermentation with glucose as a carbon source. Quantify product titer, yield, and productivity using HPLC or GC-MS.

Protocol: Sensor-Driven Evolution of Biosynthetic Pathways

This method uses biosensors to couple production of a target metabolite to cell fitness, enabling high-throughput evolution [31].

- Biosensor Selection/Engineering: Identify a natural transcriptional regulator or riboswitch responsive to the target chemical. Engineer its promoter to control the expression of a selectable marker gene (e.g., antibiotic resistance).

- Sensor-Selector Strain Construction: Integrate the biosensor circuit into the host genome. To minimize "cheater" cells, implement strategies like appending a degradation tag (ssrA tag) to the selector protein or mutating the Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) for fine-tuned translation [31].

- Library Generation: Use targeted genome-wide mutagenesis (e.g., MAGE) on genes predicted by Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to be critical for the pathway. This creates a vast library of pathway variants.

- Toggled Selection Rounds:

- Positive Selection: Grow the mutant library under antibiotic pressure. Cells producing sufficient levels of the target metabolite will activate the biosensor and survive.

- Negative Selection: Counter-screen the enriched population under conditions where the selector gene is toxic without the inducer (e.g., using a different antibiotic or SDS). This eliminates cheaters that survive via sensor malfunction.

- Iteration and Analysis: Repeat steps 3-4 for multiple rounds. Isolate evolved strains and sequence their genomes to identify causative mutations. Validate production titers with analytical methods.

Visualizing Key Metabolic Engineering Concepts

Rewiring Central Carbon Metabolism with the PHK Pathway

The diagram below illustrates how the heterologous PHK pathway integrates into native CCM to enhance flux toward acetyl-CoA and E4P, key precursors for lipids and aromatics.

Biosensor-Driven Evolution Workflow

This flowchart outlines the iterative process of using a genetically encoded biosensor to evolve high-producing strains.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This table details key genetic elements, strains, and methodologies that form the toolkit for flux enhancement research.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Resources for Flux Engineering Research

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Example/Description | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Tools [33] | Genome Editing | CRISPR-based markerless mutagenesis in E. coli [33]. | Enables precise, scarless deletion of competing genes (e.g., waaL, wecA) and integration of pathway genes. |

| Genetic Circuits [29] | Dynamic Regulation | Circuits responsive to metabolic intermediates (e.g., malonyl-CoA, acetyl-CoA). | Automatically balances cell growth and product synthesis, preventing metabolic burden. |

| Biosensors [31] | Screening & Selection | Transcription factors (e.g., TtgR, TetR) or riboswitches coupled to reporter genes. | High-throughput screening of mutant libraries by linking metabolite concentration to fluorescence or survival. |

| Flux-Enhanced Strains [32] | Chassis Platform | E. coli and S. cerevisiae strains with rewired CCM (e.g., enhanced shikimate pathway flux). | Provides a pre-engineered background with high precursor supply for pathway prototyping. |

| Cell-Free Extracts [32] | Prototyping System | Lysates derived from metabolically rewired strains. | Allows for rapid in vitro testing of pathway enzymes and feasibility before in vivo implementation. |

| Flux Analysis Algorithms [34] | Computational Tool | Enhanced Flux Potential Analysis (eFPA). | Predicts relative metabolic flux changes by integrating proteomic or transcriptomic data at the pathway level. |

The data demonstrates that no single strategy is universally superior; the choice depends on the target product's metabolic demands. The heterologous PHK pathway is exceptionally powerful for products deriving from acetyl-CoA and E4P, such as fatty acids and aromatics [30]. In contrast, for pathways with complex regulation or unknown bottlenecks, sensor-driven evolution provides a powerful, non-rational method to explore a vast mutational landscape [31]. A prevailing trend is the move from static to dynamic regulation, where genetic circuits auto-regulate flux in response to metabolic status, thereby optimizing the growth-production trade-off [29].

Furthermore, the emergence of flux-enhanced strain toolkits and their corresponding cell-free extracts represents a paradigm shift, drastically accelerating the design-build-test-learn cycle [32]. Researchers can now prototype pathways in vitro using extracts with enhanced precursor supply, de-risking and informing subsequent in vivo engineering. When combined with advanced computational tools like eFPA that predict flux from omics data, these technologies provide an integrated, data-driven framework for engineering the next generation of microbial cell factories [34]. The ultimate efficiency metric in biosynthetic pathways research is the successful and rapid translation of a design into a strain that achieves industrially relevant titers, yields, and productivities, a goal now within closer reach thanks to these advanced platform strains and prototyping strategies.

Computational and Experimental Methods for Pathway Design and Implementation

Retrosynthesis and enumeration algorithms are fundamental computational tools in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. They enable the systematic design of biosynthetic pathways for the production of high-value compounds, from pharmaceuticals to industrial chemicals, by working backwards from a target molecule to identify feasible synthetic routes using available starting materials and enzymatic transformations. This guide provides an objective comparison of three prominent algorithms—FindPath, BNICE.ch, and RetroPath2.0—focusing on their operational principles, performance characteristics, and practical applications within a broader research context focused on efficiency metrics for biosynthetic pathways.

The following diagram illustrates the core operational workflows of BNICE.ch, RetroPath2.0, and FindPath, highlighting their distinct approaches to pathway exploration.

Performance and Application Comparison

The table below summarizes a direct comparison of the key operational and performance characteristics of BNICE.ch, RetroPath2.0, and FindPath, based on documented experimental implementations.

| Feature | BNICE.ch | RetroPath2.0 | FindPath |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Generalized enzymatic reaction rules [35] | Retrosynthesis search from target to sink compounds [36] | Enumeration from host organism metabolism [36] |

| Primary Output | Network of all possible intermediates and pathways [35] | Specific retrosynthetic pathways leading to sink compounds [37] [36] | Biosynthetic pathways from a chassis organism's native metabolism [36] |

| Pathway Ranking | By popularity (citations/patents) and thermodynamic feasibility [35] | Not specified in results | By pathway length and Conserved Atom Ratio (CAR) [36] |

| Typical Application | Exploring chemical space for novel derivatives [35] | Finding feasible pathways to a target molecule [36] | Designing pathways within a specific chassis organism (e.g., E. coli) [36] |

| Experimental Validation | Used to discover pathways for (S)-tetrahydropalmatine and other BIA derivatives in yeast [35] | Integrated into workflows producing L-DOPA and dopamine in E. coli [36] | Integrated into workflows producing L-DOPA and dopamine in E. coli [36] |

| Reported Output (Sample) | Generated a network of 4,838 compounds and 17,597 reactions for noscapine pathway expansion [35] | Part of a workflow achieving 0.71 g/L L-DOPA and 0.29 g/L dopamine titers in E. coli [36] | Part of a workflow achieving 0.71 g/L L-DOPA and 0.29 g/L dopamine titers in E. coli [36] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Pathway Expansion and Derivative Synthesis Using BNICE.ch

This protocol is adapted from research that expanded the noscapine biosynthetic pathway to produce analgesic and anxiolytic derivatives [35].

Workflow Diagram: BNICE.ch Pathway Expansion

Key Reagents and Solutions

- Software Tool: BNICE.ch with its library of generalized enzymatic reaction rules.

- Reference Database: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) for validating known enzymatic functions.

- Host Organism: Engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) strains producing noscapine pathway intermediates.

- Target Compounds: (S)-tetrahydropalmatine and other benzylisoquinoline alkaloid (BIA) derivatives.

Protocol for Heterologous Pathway Implementation Using FindPath and RetroPath2.0

This protocol is adapted from a study that designed and implemented pathways in E. coli for the production of L-DOPA and dopamine [36].

Workflow Diagram: Integrated Pathway Design Workflow

Key Reagents and Solutions

- Software Suite: FindPath, BNICE.ch, RetroPath2.0, ShikiAtlas Retrotoolbox, BridgIT, Selenzyme.

- Host Organism: Escherichia coli (E. coli) production chassis.

- Analytical Technique: Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) for quantifying target compound titers.

- Key Enzymes: Tyrosinase from Ralstonia solanacearum and DOPA decarboxylase from Pseudomonas putida for the L-DOPA-to-dopamine route.

The selection of an optimal retrosynthesis and enumeration algorithm is highly dependent on the specific research goals. BNICE.ch excels in the comprehensive exploration of chemical space to discover novel pathway derivatives. RetroPath2.0 is highly effective for finding feasible retrosynthetic routes from a target molecule to available building blocks. FindPath is optimal for designing pathways that are integrated into and extend the native metabolism of a specific chassis organism. As demonstrated in experimental workflows, these tools are often used in concert, leveraging their respective strengths to efficiently bridge the gap from computational design to successful in vivo implementation.

The construction of efficient biosynthetic pathways for producing value-added compounds is a central goal in synthetic biology. However, designing these pathways manually is challenging and time-consuming [38]. In recent years, computational workflows that integrate pathway generation algorithms with enzyme selection tools have emerged as powerful solutions. These platforms enable researchers to systematically design, evaluate, and implement biosynthetic routes for target molecules, significantly accelerating the development of microbial cell factories for pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and specialty chemicals.

This guide provides an objective comparison of integrated computational frameworks for biosynthetic pathway design, focusing on their core methodologies, performance characteristics, and experimental validation. The analysis is framed within a broader research context of developing efficiency metrics for biosynthetic pathways, providing drug development professionals and researchers with critical insights for tool selection and implementation.

Comparative Analysis of Integrated Platforms

The table below summarizes the core capabilities and experimental validation of major integrated platforms for computer-aided pathway design.

Table 1: Comparison of Integrated Computational Platforms for Biosynthetic Pathway Design

| Platform Name | Primary Approach | Pathway Design Tools | Thermodynamic Assessment | Enzyme Selection Method | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| novoStoic2.0 [39] | Stoichiometry-based pathway synthesis with thermodynamic evaluation | novoStoic, optStoic | dGPredictor | EnzRank (CNN-based scoring) | Hydroxytyrosol pathways (shorter routes, reduced cofactor usage) |

| Computational Workflow [40] | Retrosynthesis and enumeration with structure-based gene discovery | FindPath, BNICE.ch, RetroPath2.0 | N/A | GDEE pipeline (homology modeling & docking) | L-DOPA (0.71 g/L) and dopamine (0.21-0.29 g/L) production in E. coli |

| COMPSS Framework [41] | Generative protein sequence evaluation with composite metrics | N/A (focuses on enzyme evaluation) | N/A | Composite metrics (alignment-based, alignment-free, structure-based) | Malate dehydrogenase & copper superoxide dismutase (70-90% identity to natural) |

| BNICE.ch Workflow [35] | Biochemical network expansion and enzyme prediction | BNICE.ch | N/A | BridgIT | (S)-tetrahydropalmatine production in yeast |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Pathway Implementation for Tyrosine-Derived Compounds

Experimental Protocol: Researchers developed a computational workflow integrating retrosynthesis algorithms (FindPath, BNICE.ch, RetroPath2.0) with a structure-based gene discovery pipeline (GDEE) for selecting enzymes [40]. The methodology involved:

- Pathway Generation: Using ShikiAtlas Retrotoolbox to enumerate pathways from tyrosine to L-DOPA and dopamine with maximum 30 reaction steps and minimum atom conservation ratio of 0.34.

- Enzyme Selection: Applying the GDEE pipeline utilizing homology modeling with Modeller and molecular docking with AutoDock Vina to rank candidate enzymes based on binding affinity as a proxy for catalytic efficiency.

- Implementation: Cloning selected gene candidates into E. coli for shake-flask experiments using a mutant tyrosinase from Ralstonia solanacearum for L-DOPA production and DOPA decarboxylase from Pseudomonas putida for dopamine production.

Performance Data: The implemented pathways achieved a maximum L-DOPA titer of 0.71 g/L and dopamine titers of 0.29 g/L (known pathway) and 0.21 g/L (novel pathway) [40]. This demonstrated the workflow's effectiveness in identifying functional biosynthetic routes, including the first validated alternative pathway for dopamine in microbes.

Computational Scoring of Generated Enzymes

Experimental Protocol: A comprehensive evaluation of computational metrics for predicting enzyme functionality was conducted over multiple experimental rounds [41]:

- Sequence Generation: Three generative models (ESM-MSA, ProteinGAN, and Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction) produced sequences for malate dehydrogenase (MDH) and copper superoxide dismutase (CuSOD).

- Metric Evaluation: Twenty diverse computational metrics were assessed, including alignment-based (sequence identity), alignment-free (language model likelihoods), and structure-based scores (AlphaFold2 confidence).

- Experimental Testing: Over 500 natural and generated sequences with 70-90% identity to natural sequences were expressed, purified, and assayed for in vitro activity.

Performance Data: Initial "naive" generation resulted in mostly inactive sequences (only 19% of tested sequences were active) [41]. However, Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction showed notably better performance, generating 9/18 active CuSOD enzymes and 10/18 active MDH enzymes. The developed COMPSS computational filter improved the rate of experimental success by 50-150% compared to unfiltered approaches.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and component integration in a comprehensive computer-aided workflow for biosynthetic pathway design, from initial target specification to experimental implementation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pathway Engineering

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| RetroPath2.0 [40] | Retrosynthesis workflow for pathway design | Enumeration of novel pathways from starting compounds to targets |

| BNICE.ch [40] [35] | Biochemical Network Integrated Computational Explorer for pathway expansion | Generation of hypothetical chemical space around pathway intermediates |

| Selenzyme [40] | Enzyme selection tool for suggested reactions | Recommendation of appropriate gene candidates for desired transformations |

| BridgIT [40] [35] | Enzyme-reaction matching through structural similarity | Identification of enzymes for novel reactions by similarity to known reactions |

| dGPredictor [39] | Thermodynamic feasibility assessment | Estimation of standard Gibbs energy changes for novel reactions |

| EnzRank [39] | CNN-based enzyme-substrate compatibility scoring | Rank-ordering known enzymes for novel substrate activity |

| AutoDock Vina [40] | Molecular docking for binding affinity prediction | Ranking candidate enzymes in structure-based gene discovery pipelines |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) [40] [42] | Heterologous expression host for pathway implementation | Production of L-DOPA, dopamine, and other target compounds |

Integrated computational platforms have significantly advanced the field of biosynthetic pathway design by combining multiple tools into cohesive workflows. The comparison reveals distinct strengths across platforms: novoStoic2.0 provides comprehensive thermodynamic evaluation, the GDEE workflow [40] demonstrates robust experimental validation with measurable product titers, and the COMPSS framework [41] offers sophisticated enzyme functionality prediction. These tools collectively enable researchers to navigate the complex journey from pathway conception to experimental implementation with increasing predictive accuracy and success rates.

For drug development professionals, these integrated approaches offer promising strategies for accelerating the production of pharmaceutical compounds and their derivatives, ultimately contributing to more efficient and sustainable biomanufacturing pipelines. As these platforms continue to evolve, they will likely incorporate more sophisticated machine learning approaches and expanded biochemical databases to further improve their predictive capabilities and experimental success rates.

Natural Products (NPs) are organic compounds synthesized by living organisms and represent a vital source for drug discovery, with over 60% of FDA-approved small-molecule drugs being NPs or their derivatives [43] [44]. However, the biosynthetic pathways for over 90% of natural products remain uncharacterized, creating a major bottleneck for their scalable production and engineering [44]. Traditional rule-based computational methods face significant challenges in predicting these complex pathways.

Deep learning approaches are overcoming these limitations by enabling template-free retrosynthetic analysis. This guide provides an objective performance comparison of BioNavi-NP, a dedicated toolkit for NP biosynthetic pathway prediction, against other emerging computational tools, with experimental data contextualized within efficiency metrics for biosynthetic pathway research.

Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Tools for Biosynthetic Pathway Prediction

Extensive benchmarking studies reveal how different computational tools perform on standardized datasets, allowing researchers to select the most appropriate solution for their specific needs. The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of leading tools.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of BioNavi-NP and Alternative Tools on Standard Benchmarks

| Tool / Model | Core Approach | Single-Step Top-1 Accuracy (%) | Single-Step Top-10 Accuracy (%) | Multi-Step Pathway Recovery Rate (%) | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioNavi-NP [43] | Transformer + AND-OR Tree Search | 21.7 (Ensemble) | 60.6 (Ensemble) | 72.8 | Data augmentation with organic reactions; Navigable AND-OR tree planning |

| GSETransformer [44] | Graph-Sequence Enhanced Transformer | Information not available in search results | State-of-the-art on BioChem benchmarks | Information not available in search results | Integrates molecular graph data with SMILES sequences |

| READRetro [44] | Ensemble (Graph2SMILES + Retroformer) | Information not available in search results | Competitive results on BioChem benchmarks | Information not available in search results | Ensemble model combining graph and sequence-based architectures |

| RetroPathRL [43] | Rule-based + Reinforcement Learning | ~10.6 (Estimated from comparison) | ~42.1 (Estimated from comparison) | Information not available in search results | Conventional rule-based approach; Lower accuracy than deep learning methods |

BioNavi-NP demonstrates a significant performance advantage, with its top-10 single-step accuracy being 1.7 times higher than conventional rule-based approaches like RetroPathRL [43]. Furthermore, it successfully identified biosynthetic pathways for 90.2% of test compounds and recovered the exact reported building blocks for 72.8% of them in multi-step planning tests [43]. The emerging GSETransformer model highlights a trend toward integrating structural graph information with sequential SMILES data to better handle molecular complexity [44].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Understanding the experimental methodologies used to generate performance data is crucial for interpreting results and planning new research.

BioNavi-NP's Training and Evaluation Protocol

BioNavi-NP's performance was validated through a rigorously defined experimental workflow [43].

- Dataset Curation (BioChem): The model was primarily trained on a dataset curated from public databases like MetaCyc, KEGG, and MetaNetX, containing 33,710 unique precursor-metabolite pairs [43].

- Data Augmentation (USPTO_NPL): To enhance robustness, the training set was expanded with 62,370 organic reactions involving natural product-like compounds from the USPTO database, creating a combined dataset of ~96,000 reactions [43].

- Model Architecture and Training: The core single-step prediction model uses a Transformer neural network, an attention-based architecture effective for sequence-to-sequence tasks. An ensemble of four such models was employed to improve prediction robustness [43].

- Multi-Step Planning Algorithm: For multi-step pathways, BioNavi-NP employs a deep learning-guided AND-OR tree-based search algorithm. This efficiently navigates the combinatorial explosion of possible routes by strategically expanding the most promising precursor candidates [43].

- Evaluation Metrics: The model was evaluated on a held-out test set of 1,000 biosynthetic reactions for single-step accuracy and 368 internal test cases for multi-step pathway recovery [43].

The following diagram visualizes this integrated workflow for biosynthetic pathway prediction.

Figure 1: BioNavi-NP's integrated workflow combines data from biological and chemical sources with a two-stage prediction process.

Benchmarking Protocol for Comparative Studies

Independent studies comparing multiple tools, such as the evaluation of GSETransformer, follow a standardized protocol to ensure fairness [44].

- Benchmark Datasets: Models are trained and tested on public benchmarks like USPTO-50K (for general organic synthesis) and BioChem Plus (for biosynthesis). The dataset is split into training, validation, and test subsets (e.g., 80%/10%/10%) [44].

- Strict Splitting: To evaluate generalization, a "clean" dataset version is sometimes created by removing all reactions present in the multi-step test set from the training data, preventing data leakage [44].

- Consistent Evaluation Metrics: All models are compared using the same metrics, primarily top-k accuracy for single-step prediction and pathway recovery rate for multi-step planning [44].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Pathway Prediction

The development and application of tools like BioNavi-NP rely on a foundation of publicly available data and software resources. The table below catalogues key reagents for computational biosynthetic research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Databases for Computational Biosynthesis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to Pathway Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG [45] [46] | Reaction/Pathway Database | Reference repository of known metabolic pathways and enzymes. | Source of known pathways for training and validation; reference for pathway reconstruction. |

| MetaCyc [43] [46] | Reaction/Pathway Database | Curated database of experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways and enzymes. | Provides high-quality, curated biochemical reactions for model training. |

| USPTO [43] | Reaction Database | Large repository of organic chemical reactions extracted from patents. | Source for data augmentation to improve model robustness and generalizability. |

| PubChem [46] | Compound Database | Public repository of chemical compound structures and properties. | Essential for compound look-up, structure verification, and property calculation. |

| BRENDA [46] | Enzyme Database | Comprehensive enzyme information database detailing function and kinetics. | Used for linking predicted biochemical reactions to plausible enzymes. |

| RXNMapper [44] | Software Tool | Automated atom-mapping tool for chemical reactions. | Critical pre-processing step to define reaction centers in training data for template-free models. |

| Selenzyme / E-zyme [43] | Software Tool | Enzyme prediction tools that recommend potential enzymes for a given reaction. | Downstream application to assign putative enzymes to each step in a predicted pathway. |

The logical relationship between these resources in a typical research pipeline is illustrated below.

Figure 2: Research reagent workflow shows how data flows from foundational databases through analysis tools to final predictions.

Deep learning approaches like BioNavi-NP represent a significant advancement over traditional rule-based systems for predicting the biosynthetic pathways of natural products. Quantitative benchmarks demonstrate its superior accuracy in single-step retrosynthesis and high efficacy in multi-step pathway recovery.

The field is rapidly evolving, with new architectures like GSETransformer pushing the boundaries of performance by more effectively integrating molecular structure information. For researchers in drug discovery and metabolic engineering, these tools are becoming indispensable for accelerating the elucidation of complex biosynthetic pathways, thereby facilitating the sustainable production of valuable plant natural products and novel bioactive compounds [47]. The continued integration of large-scale multi-omics data with sophisticated deep learning models promises to further unlock the synthetic potential of natural product biosynthesis.

Multi-omics integration represents a transformative approach in biological research, enabling a holistic interpretation of molecular intricacy across multiple levels including genome, transcriptome, and metabolome [48]. This paradigm has revolutionized the field of medicine and biology by creating avenues for integrated system-level approaches that bridge the gap from genotype to phenotype [48]. For researchers investigating biosynthetic pathways, multi-omics provides powerful tools to unravel the complex interplay between genes, their expression patterns, and the resulting metabolic outputs that define cellular functions. Integrated approaches combine individual omics data, either sequentially or simultaneously, to understand the interplay of molecules and assess the flow of information from one omics level to another [48]. The advent of high-throughput techniques and availability of multi-omics data generated from large sample sets has catalyzed the development of numerous computational tools and methods for data integration and interpretation, creating new opportunities for discovering genes involved in specialized metabolism [48] [49].

For biosynthetic pathway research, efficiency metrics are increasingly dependent on multi-omics approaches that can simultaneously capture genomic potential, transcriptional activity, and metabolic outputs. Where single-omics studies provide limited snapshots of biological systems, integrated multi-omics enables researchers to connect genetic blueprints with functional outcomes, thereby accelerating the identification of key genes and regulatory elements controlling biosynthetic pathways [49]. This comprehensive review examines current methodologies, performance comparisons, and practical implementations of multi-omics integration specifically for gene discovery in biosynthetic pathways, providing researchers with critical insights for selecting appropriate strategies based on their specific research objectives and available data types.

Performance Comparison of Multi-omics Integration Methods

Benchmarking Results Across Methodologies

Multi-omics integration methods demonstrate varying performance characteristics depending on data types, biological context, and analytical goals. The table below summarizes quantitative performance metrics for prominent integration approaches applied to biosynthetic pathway discovery and gene identification.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Multi-omics Integration Methods

| Method | Omics Layers Integrated | Primary Application | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioNavi-NP [43] | Genomic, Metabolomic | Natural product biosynthetic pathway prediction | 90.2% pathway identification rate; 72.8% building block recovery (1.7x better than rule-based) | Deep learning-based; handles complex natural products |

| MINIE [50] | Transcriptomic, Metabolomic | Causal network inference | Significant improvement over state-of-art methods; robust performance in curated networks | Bayesian approach; handles timescale separation; infers causal relationships |

| Network Propagation [51] | Genomic, Transcriptomic, Metabolomic | Drug target identification | Varies by implementation; superior for identifying novel disease modules | Leverages prior biological knowledge; captures system-level properties |

| Graph Neural Networks [51] | Multi-omics layers | Drug response prediction | High accuracy in heterogeneous data integration | Captures complex non-linear relationships; adaptable to various network structures |

| Early Data Fusion (Concatenation) [52] | Genomic, Transcriptomic, Metabolomic | Genomic prediction | Inconsistent results; often underperforms vs. model-based integration | Simple implementation; minimal preprocessing requirements |

| Model-based Fusion [52] | Genomic, Transcriptomic, Metabolomic | Complex trait prediction | Consistently improves predictive accuracy over genomic-only models | Captures non-additive, nonlinear, and hierarchical interactions |

Performance Analysis and Method Selection Guidelines

The benchmarking data reveals that method performance significantly depends on the specific research objective. For biosynthetic pathway elucidation, deep learning approaches like BioNavi-NP demonstrate superior performance in identifying complete pathways and recovering known building blocks [43]. Transformer neural networks trained on both biochemical and organic reactions achieve top-10 precursor prediction accuracy of 60.6%, substantially outperforming conventional rule-based approaches [43].

For inferring regulatory mechanisms and causal relationships, Bayesian methods like MINIE that explicitly model temporal dynamics and timescale separation between molecular layers show significant advantages [50]. These approaches successfully capture the reality that metabolic processes occur on much faster timescales (minute-level) compared to transcriptional changes (hour-level), leading to more biologically plausible network inferences [50].

In genomic prediction contexts, model-based integration strategies consistently outperform simple data concatenation approaches, particularly for complex traits influenced by multiple biological layers [52]. Methods that capture non-additive, nonlinear, and hierarchical interactions across omics layers provide more accurate predictions of phenotypic outcomes, enabling more efficient selection in breeding programs [52].

Experimental Protocols for Multi-omics Integration

Protocol 1: Integrated Pathway Discovery Using BioNavi-NP

Objective: Identification of complete biosynthetic pathways for natural products using multi-omics data.

Experimental Workflow:

Data Preparation: Curate genomic and metabolomic data for target organism. For novel natural products, obtain high-resolution mass spectrometry data and NMR spectra for structural elucidation [43].

Single-step Retrosynthesis Prediction:

- Input target natural product as SMILES representation

- Apply ensemble transformer neural networks to predict potential biosynthetic precursors

- Generate top-k precursor candidates (typically k=10) based on trained model [43]

Multi-step Pathway Planning:

- Implement AND-OR tree-based search algorithm to explore combinatorial pathway options

- Iterate single-step predictions recursively until reaching known building blocks

- Rank complete pathways by computational cost, length, and organism-specific enzyme availability [43]

Experimental Validation:

- Express candidate genes in heterologous system (e.g., yeast, E. coli)

- Analyze metabolic intermediates using LC-MS/MS

- Confirm pathway completeness through isotope labeling experiments

Figure 1: BioNavi-NP Pathway Discovery Workflow

Protocol 2: Causal Network Inference with MINIE

Objective: Infer regulatory networks integrating transcriptomic and metabolomic data to identify key regulatory genes.

Experimental Workflow:

Time-Series Data Collection:

- Collect single-cell RNA-seq data at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 6, 12, 24, 48 hours)

- Obtain bulk metabolomic measurements from same biological system at matched time points [50]

Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize transcript counts using standard scRNA-seq pipelines

- Transform metabolomic data using probabilistic quotient normalization

- Align temporal measurements across omics layers

Network Inference:

- Implement differential-algebraic equation model to handle timescale separation

- Apply Bayesian regression framework to infer network topology

- Incorporate curated metabolic reaction networks as prior knowledge [50]

Validation and Interpretation:

- Perform gene ontology enrichment on identified regulatory genes

- Validate key interactions through targeted gene knockdown experiments

- Compare network topology with known pathway databases

Figure 2: MINIE Causal Network Inference Protocol

Computational Tools and Databases

Table 2: Essential Multi-omics Research Resources

| Resource | Type | Function | Application in Biosynthetic Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA [48] | Data Repository | Provides multi-omics data for cancer samples | Comparative analysis of secondary metabolism in disease contexts |

| ICGC [48] | Data Repository | Coordinates large-scale cancer genome studies | Access to somatic mutation data affecting metabolic pathways |

| CCLE [48] | Data Repository | Gene expression, copy number, sequencing from cancer cell lines | Screening model systems for pathway engineering |