Machine Learning for Biosynthetic Pathway Optimization: From AI-Driven Discovery to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing the optimization of biosynthetic pathways for drug development and natural product synthesis.

Machine Learning for Biosynthetic Pathway Optimization: From AI-Driven Discovery to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing the optimization of biosynthetic pathways for drug development and natural product synthesis. It explores foundational AI concepts, details specific methodologies like deep learning-driven retrobiosynthesis and automated platform integration, addresses troubleshooting through predictive optimization and thermodynamic feasibility checks, and validates approaches with comparative performance analyses. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes recent advances to offer a practical guide for leveraging ML to accelerate and enhance biosynthetic engineering.

Laying the Groundwork: Core AI Concepts and the New Era of Biosynthetic Pathway Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

Pathway Discovery and Elucidation

FAQ: A biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) has been identified in a native producer through genome mining, but the natural product is not detected under standard laboratory conditions. What are the primary strategies to activate this silent cluster?

- Answer: Two complementary, primary strategies can be employed to activate silent BGCs, each with specific considerations.

- Strategy 1: Activation in the Native Producer. This approach aims to work within the native regulatory network.

- Method: Implement genomic-based approaches, such as the overexpression of pathway-specific positive regulators (e.g., SARP family regulators) or the deletion of repressors. Concurrently, epigenetic approaches can be used, including co-culture with other microbes, variation of fermentation media, and application of environmental stressors [1].

- Troubleshooting:

- Problem: Low or no production persists after regulator manipulation.

- Solution: Conduct RT-PCR analysis to compare transcription levels of key biosynthetic genes between manipulated and wild-type strains. This can identify silent "bottleneck" steps in the pathway that may require co-overexpression of specific biosynthetic genes [1].

- Strategy 2: Heterologous Expression in a Model Host. This strategy severs the cluster from its native, and potentially complex, regulatory context.

- Method: Clone the entire BGC into a genetically tractable host like Streptomyces albus J1074 or E. coli [1].

- Troubleshooting:

- Problem: The cluster remains silent in the heterologous host.

- Solution: Co-introduce and express the pathway-specific positive regulator from the native cluster into the heterologous host. The regulator itself may need to be placed under a strong, constitutive promoter (e.g., ErmE*) to ensure sufficient expression [1].

- Problem: Production titer in the heterologous host is significantly lower than in the native producer.

- Solution: As with the native producer, use transcriptomic analysis (RT-PCR) to identify poorly expressed biosynthetic genes in the heterologous system. The host's native metabolic capacity may not supply sufficient precursors, so medium optimization and precursor feeding should also be investigated [1].

- Strategy 1: Activation in the Native Producer. This approach aims to work within the native regulatory network.

FAQ: For a novel natural product, the complete biosynthetic pathway is unknown. What computational tools can predict potential pathways from simple building blocks?

- Answer: Traditional rule-based systems are limited by pre-defined biochemical reaction rules. Modern, deep learning-based tools like BioNavi-NP have demonstrated superior performance for this task [2].

- Method: BioNavi-NP uses an end-to-end transformer neural network model trained on both general organic and biosynthetic reactions. It performs iterative multi-step bio-retrosynthetic planning using an AND-OR tree-based algorithm to propose pathways from essential building blocks to the target NP [2].

- Troubleshooting:

- Problem: The predicted pathway contains enzymatically infeasible steps.

- Solution: Use integrated enzyme prediction tools like Selenzyme or E-zyme 2 to evaluate each predicted biosynthetic step for a plausible enzyme candidate. This adds a layer of biological validation to the computational prediction [2].

Pathway Optimization and Machine Learning Integration

FAQ: An initial, low-yielding biosynthetic pathway has been established in a microbial host. How can Machine Learning (ML) be applied to optimize the metabolic flux without exhaustive trial-and-error experimentation?

- Answer: ML can bypass the need for fully elucidated mechanistic models by learning the complex relationships between genetic modifications and metabolic phenotypes [3].

- Method: As demonstrated for phytoene production, an ML framework can be established by:

- Defining a Design Space: Identify key genes in the pathway and a library of genetic parts (e.g., promoters of different strengths) to control their expression.

- Generating a Training Dataset: Construct a subset of possible genetic variants and measure their production titers.

- Model Training and Prediction: Train ML models (e.g., Deep Neural Networks - DNN, Support Vector Machines - SVM) on this data to predict the optimal combination of parts for maximum production [3].

- Troubleshooting:

- Problem: Insufficient experimental data is available to train an accurate ML model, which is common for non-model organisms or new pathways.

- Solution: Employ data augmentation techniques. For example, use a Conditional Tabular Generative Adversarial Network (CTGAN) to generate high-quality synthetic experimental data that mimics the limited real dataset, thereby enhancing the model's predictive accuracy [3].

- Method: As demonstrated for phytoene production, an ML framework can be established by:

FAQ: During a directed evolution campaign to improve product titer, "cheater" mutants that survive selection without producing the target compound emerge and take over the population. How can this be prevented?

- Answer: A "toggled selection" scheme can be implemented to eliminate cheaters while preserving library diversity [4].

- Method: This strategy uses a biosensor that couples intracellular product concentration to cell survival (e.g., via antibiotic resistance). The scheme alternates between:

- Positive Selection: Apply antibiotic pressure to enrich for high-producing cells.

- Negative Selection: Apply a mechanism that selectively kills cells that survived the positive selection without the target compound present, thereby purging cheaters [4].

- Troubleshooting:

- Problem: High basal "leakiness" of the selection system leads to a high background of cheaters.

- Solution: Engineer the sensor-selector system to reduce leakiness. This can be achieved by appressing a degradation tag (e.g., ssrA tag) to the selector protein to reduce its half-life, or by mutating the Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) to attenuate its translation [4].

- Method: This strategy uses a biosensor that couples intracellular product concentration to cell survival (e.g., via antibiotic resistance). The scheme alternates between:

Key Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Optimizing a Pathway using a Biosensor-Driven Evolution

This protocol is adapted from a general strategy that combines targeted genome-wide mutagenesis with evolution to enrich for high-producing variants [4].

Objective: To increase the production of a target natural product (e.g., naringenin, glucaric acid) in E. coli.

Materials:

- Strain: E. coli host strain harboring the baseline biosynthetic pathway.

- Plasmid: Sensor-selector plasmid, where a biosensor for the target compound controls the expression of a selector gene (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene).

- Mutagenesis Tools: Resources for multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE) or CRISPR-Cas9 to target candidate genes identified by flux balance analysis.

- Selection Media: Growth media containing the appropriate antibiotic for selection.

Methodology:

- Strain Development: Transform the sensor-selector plasmid into the production host. Validate that the survival of this strain in selective media is dependent on the presence of the target compound.

- Library Generation: Use targeted genome-wide mutagenesis (e.g., MAGE) to create a diverse library of pathway variants by mutating regulatory regions or coding sequences of key genes involved in the biosynthesis.

- Toggled Selection Rounds:

- a. Positive Selection: Incubate the mutant library in selective media containing the antibiotic. High-producing cells will activate the biosensor, express the resistance gene, and survive.

- b. Negative Selection: Take the enriched population from (a) and grow it in the presence of a mechanism that kills cells expressing the selector protein, but only in the absence of the target compound. This step eliminates cheaters that survive via sensor/selector mutations.

- c. Iteration: Repeat steps (a) and (b) for multiple rounds to progressively enrich the population for superior producers.

- Validation: Isolate individual clones from the final evolved population and quantify product titer using analytical methods (e.g., HPLC-MS) [4].

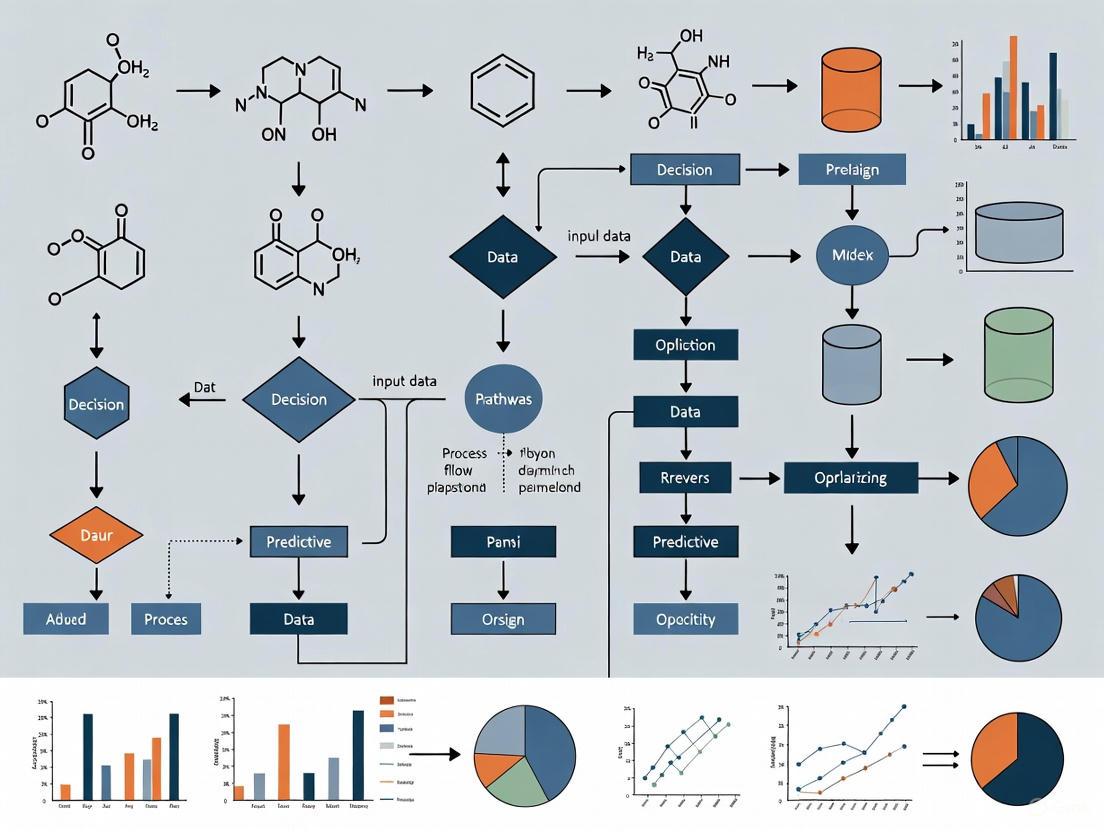

Workflow Diagram: ML-Guided Pathway Optimization

The workflow below illustrates the machine learning-guided design-build-test-learn cycle for pathway optimization.

Data Presentation: Performance of Advanced Methods

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Biosynthetic Pathway Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Methodology | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioNavi-NP | Deep learning (Transformer neural networks) with AND-OR tree-based planning | Top-10 accuracy on single-step bio-retrosynthesis test set | 60.6% | [2] |

| RetroPathRL | Rule-based model (Reinforcement Learning) | Top-10 accuracy on single-step bio-retrosynthesis test set | ~35.7% | [2] |

| BioNavi-NP | Deep learning multi-step planning | Recovery rate of reported building blocks in test set | 72.8% | [2] |

Table 2: Titer Improvements via Sensor-Driven Directed Evolution

| Target Compound | Host Organism | Selection Strategy | Fold Improvement | Final Titer | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naringenin | E. coli | Biosensor-coupled, toggled selection | 36-fold | 61 mg/L | [4] |

| Glucaric Acid | E. coli | Biosensor-coupled, toggled selection | 22-fold | Not Specified | [4] |

| Fredericamycin A | S. griseus (Native) | Overexpression of pathway-specific regulator (fdmR1) | 6-fold | ~1 g/L | [1] |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosynthetic Pathway Engineering

| Item | Function / Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Hosts | Genetically tractable chassis for expressing BGCs from difficult-to-culture native producers. | Streptomyces albus J1074, S. lividans K4-114 [1] |

| Constitutive Promoters | To drive strong, consistent expression of biosynthetic or regulatory genes in heterologous systems. | ErmE* promoter [1] |

| Pathway-Specific Regulators | Positive regulators (e.g., SARP family) used to activate silent BGCs in native and heterologous hosts. | FdmR1 for fredericamycin A [1] |

| Biosensors | Proteins or RNAs that convert intracellular metabolite concentration into a measurable output (fluorescence, survival). | MphR, TtgR, TetR-based sensors [4] |

| Biological Databases | Resources for compounds, reactions, pathways, and enzymes essential for computational pathway design. | KEGG, MetaCyc, UniProt, BRENDA, PubChem [5] |

| Machine Learning Models | Algorithms for predicting optimal pathways and optimizing gene expression. | Deep Neural Networks (DNN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) for data augmentation [3] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) in the context of biological research?

A1: Machine Learning is a branch of artificial intelligence that focuses on building systems that learn from data to make predictions or decisions without being explicitly programmed. In biology, it encompasses various algorithms like random forests and support vector machines for tasks such as classifying cell types or predicting protein function [6]. Deep Learning is a specialized subset of ML that uses multi-layered artificial neural networks. DL is particularly powerful for handling complex, high-dimensional biological data, such as predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences with tools like AlphaFold, or analyzing microscopic images [7] [8] [9]. While ML often relies on human-engineered features, DL can automatically learn relevant features directly from raw data.

Q2: I am trying to predict the yield of a target metabolite from a newly engineered microbial strain. Which ML model should I start with?

A2: For predictive modeling tasks like forecasting metabolite yield, an ensemble method like Random Forest or Gradient Boosting Machines is an excellent starting point [10] [6]. These models are highly effective at capturing complex, non-linear relationships within multi-omics data (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics) and genotype-phenotype interactions. They also provide estimates of feature importance, helping you identify which enzymes or genetic modifications most significantly impact your product's titer, rate, or yield (TRY) [10].

Q3: How can AI assist in discovering a completely new biosynthetic pathway for a natural product?

A3: AI leverages retrosynthesis analysis and network analysis to predict novel biosynthetic pathways [11] [5]. By mining extensive biological big-data—including compound structures in PubChem or ChEBI, known reactions in KEGG or MetaCyc, and enzyme functions in BRENDA or UniProt—AI algorithms can propose a series of plausible enzymatic reactions to synthesize a target compound from available precursors [5]. This approach drastically reduces the massive search space that researchers would otherwise need to explore manually.

Q4: What are the most common data-related bottlenecks when applying Deep Learning to pathway optimization, and how can I avoid them?

A4: The most common bottlenecks are insufficient data volume, poor data quality, and lack of standardization [10] [12]. Deep Learning models typically require large, well-curated datasets to perform effectively.

- Solution: Prioritize data standardization and curation. Use consistent formats and metadata for all your experimental results. Leverage publicly available biological databases to pre-train models, a technique known as transfer learning, which can improve performance even with smaller, domain-specific datasets [5] [12] [8].

Q5: Can AI help optimize the experimental process itself, not just the design?

A5: Yes, absolutely. AI-driven experimental design is transforming the traditional Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle [7] [10]. Techniques like active learning and Bayesian optimization can analyze prior experimental data to propose the most informative next experiments. This intelligent prioritization minimizes the number of required lab experiments, accelerating the overall optimization of pathways and host strains by focusing resources on the most promising genetic edits or culture conditions [7] [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Performance of an ML Model in Predicting Enzyme Function

Symptoms: Low accuracy, precision, and recall on test data; model fails to generalize to new, unseen enzyme sequences.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Training Data | Check the size and diversity of your labeled dataset. | Use data augmentation techniques or leverage a pre-trained Protein Language Model (pLM) and fine-tune it on your specific data, which requires fewer examples [7] [8]. |

| Inadequate Feature Representation | Evaluate if handcrafted features (e.g., amino acid frequency) capture relevant information. | Shift to learned sequence embeddings from a pLM, which provides a richer, context-aware representation of protein sequences [8]. |

| Class Imbalance | Check the distribution of examples across different functional classes. | Apply sampling techniques (e.g., SMOTE) or use weighted loss functions during model training to penalize misclassifications of the minority class more heavily [6]. |

Issue 2: Inefficient DBTL Cycles for Metabolic Pathway Optimization

Symptoms: Each "Learn" phase fails to generate productive hypotheses for the next "Design" phase; strain performance plateaus after few iterations.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Isolated Data Silos | Check if omics data, fermentation data, and genetic design data are stored in disconnected formats. | Implement a unified, machine-readable data management system to integrate diverse data types, enabling AI models to uncover complex, non-obvious correlations [12]. |

| Testing Bottlenecks | Assess the throughput of your strain construction and screening methods. | Integrate high-throughput automation and microfluidics to rapidly build and test thousands of variant strains, generating the large-scale data needed for robust AI learning [7] [12]. |

| Suboptimal Experimental Design | Review if new experiments are chosen based on intuition rather than data. | Implement Bayesian optimization to intelligently select strain variants or culture conditions that maximize information gain and performance improvement for the next DBTL cycle [10]. |

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential data resources and computational tools for AI-driven biosynthetic pathway research.

| Category | Item Name | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | PubChem [5] | Provides chemical structures, properties, and biological activities for millions of compounds, serving as a foundation for pathway prediction. |

| ChEBI [5] | A curated dictionary of small molecular entities, focusing on standardized chemical nomenclature. | |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG [5] | A comprehensive database integrating genomic, chemical, and systemic functional information, including known metabolic pathways. |

| MetaCyc [5] | A curated database of experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways and enzymes from various organisms. | |

| Enzyme Databases | BRENDA [5] | The main enzyme information system, providing comprehensive data on enzyme function, kinetics, and substrate specificity. |

| UniProt [5] | A high-quality resource for protein sequence and functional information with extensive curation. | |

| AI Tools | Protein Language Models (pLMs) [8] | Pre-trained deep learning models (e.g., from ESM, ProtTrans) used for predicting protein structure and function from sequence. |

| Retrosynthesis Tools [5] | Computational software that uses biochemical rules to predict potential biosynthetic routes to a target molecule. |

Essential Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: AI-Augmented DBTL Cycle for Pathway Optimization

This protocol outlines an iterative workflow for optimizing biosynthetic pathways using AI, integrating several key techniques [7] [10].

1. Design Phase:

- Input: Target molecule structure, host organism genomics, and databases of known reactions (e.g., MetaCyc).

- Action: Use a retrosynthesis algorithm to generate possible biosynthetic pathways. Rank pathways based on predicted efficiency, enzyme availability, and host compatibility.

- AI Technique: Rule-based network analysis combined with machine learning for pathway scoring [11] [5].

2. Build Phase:

- Action: Engineer the host strain by assembling the selected pathway using genetic engineering tools (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9). For key, low-activity enzymes, use protein language models to design optimized variants.

- AI Technique: AI-guided gRNA design for CRISPR; Deep learning (e.g., Variational Autoencoders, Diffusion Models) for de novo protein design [7] [8].

3. Test Phase:

- Action: Cultivate the engineered strain and measure key performance indicators (TRY). Use high-throughput analytics (e.g., LC-MS) to generate multi-omics data (transcriptomics, metabolomics).

- Data Output: Structured datasets linking genotype (DNA sequence, expression) to phenotype (metabolite concentration, growth rate) [10].

4. Learn Phase:

- Action: Integrate all new experimental data into a unified database. Train supervised ML models (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) to predict strain performance from genetic design features.

- AI Technique: Ensemble learning models to identify the most impactful genetic modifications for the next Design phase [10] [6].

The following diagram visualizes this iterative, AI-driven cycle:

Protocol 2: Workflow for Engineering a Non-Natural Product Pathway

This protocol describes a specific application for producing novel compounds, such as the vaccine adjuvant QS-21 in yeast [12].

1. Pathway Discovery & Enzyme Identification:

- Action: If the pathway exists in a non-model organism (e.g., a plant), use transcriptomic analysis across different growth stages to identify candidate biosynthetic genes. AI can correlate gene expression with product accumulation to pinpoint key enzymes [12].

2. Host Engineering for Precursor Supply:

- Action: Engineer the microbial host (e.g., S. cerevisiae) to supply necessary precursors. This may involve knocking out competing pathways and overexpressing genes in the precursor's native metabolic network. Use ML models trained on omics data to predict optimal expression levels and avoid metabolic burden [10] [12].

3. Assembly & Optimization of the Heterologous Pathway:

- Action: Assemble the pathway genes in the host. Use AI-driven codon optimization tools (e.g., CodonTransformer) to design DNA sequences for optimal expression in the host organism [7].

- Action: To overcome host toxicity from the product (e.g., membrane disruption by saponins), use directed evolution guided by ML. Train models on sequence-activity relationships from mutant libraries to predict stabilizing mutations with fewer experimental rounds [12] [8].

4. System-Wide Optimization via DBTL:

- Action: Implement the full AI-augmented DBTL cycle (as in Protocol 1) to iteratively refine enzyme variants, gene expression levels, and host background, pushing toward industrial-level production [10] [12].

The logical flow of this multi-stage engineering project is shown below:

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the primary computational strategies for integrating multi-omics data? Integration strategies can be categorized by the stage at which data from different omics layers are combined [13]:

- Early Integration: Features from each modality (e.g., gene expression, protein abundance) are concatenated into a single input vector before being fed into a model. This is simple but can be challenged by the high dimensionality and heterogeneity of the data [13].

- Intermediate Integration: The model learns a joint representation or a shared latent space from the separate omics inputs. Methods include deep learning architectures like autoencoders or matrix factorization techniques [14] [13].

- Late Integration: Separate models are trained on each omics dataset, and their predictions are combined at the final stage. This approach can be more robust to modality-specific noise [13].

FAQ 2: How can I handle missing omics data in my models? Missing data is a common challenge in multi-omics studies. Several computational approaches can address this [13]:

- Generative Models: Deep learning methods like variational autoencoders (VAEs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) can be trained to impute missing modalities by learning the underlying data distribution [15] [13].

- Mosaic Integration: Tools like COBOLT and MultiVI are designed to integrate datasets where each sample has various combinations of omics measured, creating a single representation across all cells or samples [16].

- Bayesian Methods: These can be used to account for uncertainty introduced by missing values [13].

FAQ 3: Why don't my multi-omics models perform better than single-omics models? This can occur for several reasons [16]:

- Disconnect Between Modalities: The biological correlation between omics layers may be weak or non-linear for your specific use case. For example, high mRNA transcript levels do not always correlate with high protein abundance [16].

- Limited Proteomics/Metabolomics Breadth: Proteomic or metabolomic assays may profile far fewer features (e.g., ~100 proteins) compared to transcriptomics (thousands of genes), making it difficult to capture cross-modality relationships [16].

- Incorrect Tool Selection: The chosen method might be unsuitable for your data structure (e.g., using a tool for matched data on unmatched samples) or your specific biological objective [14] [16].

FAQ 4: What deep learning architecture is best for multi-omics integration? There is no single "best" architecture; the choice depends on the task, data structure, and desired outcome. The table below summarizes common deep learning approaches used in multi-omics integration [15] [13]:

| Architecture Category | Key Strengths | Common Use Cases | Example Tools / Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Generative (e.g., Autoencoders, FNNs) | Learns compressed, low-dimensional representations; good for dimensionality reduction and clustering [15] [13]. | Disease subtyping, feature extraction, joint latent space learning [15]. | MOLI (late integration), MOGONET [13] |

| Generative (e.g., VAEs, GANs) | Can impute missing data, perform data augmentation, and learn robust latent representations; handles uncertainty [15] [13]. | Data imputation, augmentation, denoising, and integration of incomplete datasets [15] [13]. | scMVAE, totalVI, VIPCCA [15] [16] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Models complex biological relationships and interactions as networks; incorporates prior knowledge [17] [13]. | Modeling gene regulatory networks, patient similarity networks, and cellular communication [17] [13]. | Graph Linked Unified Embedding (GLUE) [16] |

FAQ 5: How do I choose the right omics layers to integrate for my study? The selection should be guided by your specific biological objective. The following table outlines common trends based on research goals in translational medicine [14] [18]:

| Research Objective | Recommended Omics Combinations | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Disease Subtype Identification | Transcriptomics, Epigenomics, Proteomics | Captures functional state and regulatory mechanisms defining subtypes [14]. |

| Understanding Regulatory Processes | Transcriptomics, Epigenomics (e.g., Chromatin Accessibility), Genomics | Identifies interactions between genetic variation, gene regulation, and expression [14]. |

| Drug Response Prediction | Genomics, Transcriptomics, Proteomics | Links genetic mutations, expression changes, and protein targets to therapeutic efficacy [14] [19]. |

| Detecting Disease-Associated Patterns | Genomics, Transcriptomics, Metabolomics | Connects genetic predisposition to functional pathway changes and end-stage phenotypic molecules [14] [20]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Model Performance is Poor Due to Data Heterogeneity and Technical Noise

- Symptoms: The model fails to converge, shows high error on validation data, or cannot identify biologically meaningful patterns.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Batch effects and technical variation between datasets.

- Solution: Apply batch effect correction methods before integration. Tools like ComBat or those built into integration frameworks (e.g., MOFA+) can attenuate technical biases while preserving biological signals [15].

- Cause: Major differences in data scale, distribution, and noise profiles between omics types.

- Solution: Ensure robust pre-processing. This includes careful normalization, scaling, and transformation of each omics dataset individually to make them more comparable before integration [16].

- Cause: The model is not effectively capturing non-linear relationships across omics layers.

- Cause: Batch effects and technical variation between datasets.

Problem 2: Inability to Integrate Unpaired or Mosaic Datasets

- Symptoms: You have omics data from different cells or samples, and standard integration tools fail or produce misaligned embeddings.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Using a tool designed for "matched" integration (data from the same cell/sample) on "unmatched" data (data from different cells/samples) [16].

- Solution: Select a method specifically designed for unpaired or diagonal integration.

- Manifold Alignment: Methods like Pamona and UnionCom project cells from different modalities into a shared co-embedded space to find commonality [16].

- Graph-based Learning: Tools like GLUE (Graph-Linked Unified Embedding) use a graph VAE and incorporate prior biological knowledge to anchor and align features from different omics types [16].

- Mosaic Integration: For datasets where each experiment has various omics combinations, use tools like StabMap, COBOLT, or MultiVI, which are built to leverage overlapping measurements [16].

- Solution: Select a method specifically designed for unpaired or diagonal integration.

- Cause: Using a tool designed for "matched" integration (data from the same cell/sample) on "unmatched" data (data from different cells/samples) [16].

Problem 3: Lack of Interpretability and Biological Insight from the Model

- Symptoms: The model makes accurate predictions, but you cannot determine which features or biological pathways are driving the outcome.

- Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The model is a "black box," and feature importance is not inherently provided.

- Solution: Utilize model-specific interpretability techniques.

- Attention Mechanisms: If using transformers or models with attention layers, visualize the attention weights to see which input features the model "focuses" on.

- SHAP/Saliency Maps: Apply post-hoc explanation methods like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or generate saliency maps to quantify the contribution of each input feature to the final prediction [19].

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Extract the most important features from the model (e.g., genes with the highest weights) and use them as input for pathway enrichment tools (e.g., GSEA, Enrichr) to translate feature lists into biological mechanisms [20].

- Solution: Utilize model-specific interpretability techniques.

- Cause: The model is a "black box," and feature importance is not inherently provided.

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Data Repository | Provides comprehensive, publicly available multi-omics profiles (genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) from human tumor samples, serving as a benchmark for model training and validation [14]. |

| Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) | Data Repository | Offers extensive molecular profiling data from cancer cell lines, widely used for pre-clinical research, particularly in drug response prediction tasks [19]. |

| Cytoscape | Visualization & Analysis Software | Used for constructing, visualizing, and analyzing biological networks, such as gene-metabolite or protein-protein interaction networks derived from integrated data [20]. |

| Flexynesis | Deep Learning Toolkit | A flexible, modular deep learning framework that streamlines bulk multi-omics data processing, model training, and biomarker discovery for tasks like classification, regression, and survival analysis [19]. |

| MOFA+ | Integration Tool | A widely used factor analysis model that decomposes multi-omics data into a set of latent factors, providing a interpretable framework for exploring variation and identifying sources of heterogeneity across omics layers [16]. |

| Seurat | Integration Tool (Single-Cell) | A comprehensive toolkit for the analysis and integration of single-cell multi-omics data, including mRNA, chromatin accessibility, and protein data [16]. |

Experimental Workflow and Protocol for Multi-Omics Model Training

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for developing a predictive model from multi-omics data, contextualized within the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle common in biosynthetic pathway optimization [21].

Detailed Protocol:

Design & Data Collection:

- Define Objective: Clearly state the predictive goal (e.g., classify cancer subtypes, predict product titer in an engineered microbe) [14] [21].

- Select Omics: Choose omics layers based on the objective (refer to FAQ 5 table). For biosynthetic pathway optimization, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics are often central [21].

- Generate Data: Perform high-throughput sequencing (genomics, transcriptomics), mass spectrometry (proteomics, metabolomics), and other assays on your biological samples. Public data from TCGA or CCLE can be used for validation [14] [19].

Preprocessing & Integration:

- Quality Control: Remove low-quality samples and features. For RNA-seq, this includes adapter trimming and assessing sequencing depth.

- Normalization: Apply modality-specific normalization (e.g., TPM for RNA-seq, median normalization for proteomics) to make data comparable across samples.

- Batch Correction: Use statistical methods to remove non-biological technical variation introduced by different experimental batches [15].

- Integration: Choose and apply an integration method (see FAQ 1 and 4). For example, use an autoencoder to learn a joint latent representation of all omics layers for downstream tasks [15] [13].

Model Training & Validation:

- Architecture Selection: Select a model based on your data and goal. For instance, use a VAE for data with missing modalities or a multi-task learning framework (e.g., Flexynesis) to predict multiple outcomes simultaneously [13] [19].

- Training: Split data into training, validation, and test sets. Train the model on the training set.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize model parameters using the validation set to prevent overfitting.

- Validation: Evaluate the final model's performance on the held-out test set using appropriate metrics (e.g., AUC for classification, Concordance Index for survival).

Biological Interpretation & Learning:

- Feature Importance: Identify which molecular features (e.g., genes, metabolites) were most influential in the model's predictions using interpretability methods [19].

- Pathway Analysis: Input the top features into pathway analysis tools to uncover dysregulated biological processes or metabolic pathways [20].

- Hypothesis Generation: Use these insights to form new biological hypotheses (e.g., "Gene X is a key regulator of the pathway leading to product Y"), which can then be tested experimentally, thus closing the DBTL cycle [21].

This technical support center addresses common experimental challenges in the study of four major classes of natural products: terpenoids, alkaloids, polyketides, and non-ribosomal peptides (NRPs). These compounds serve as vital resources for drug discovery, boasting diverse pharmacological activities. The integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing this field, enhancing the identification, optimization, and engineering of these complex biosynthetic pathways. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting advice and detailed protocols to help researchers navigate technical obstacles and leverage computational tools for more efficient and successful outcomes.

Terpenoid Biosynthesis Pathway

Terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, represent one of the most abundant classes of natural products. Their biosynthesis proceeds via two primary pathways: the mevalonate (MVA) pathway, predominantly in eukaryotes, and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway, found in prokaryotes and plant plastids. Both pathways converge on the production of the universal C5 precursors, isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP). These precursors are subsequently assembled into larger structures by prenyltransferases, and then cyclized and functionalized by terpene synthases and cytochrome P450 enzymes to generate immense structural diversity [22] [23].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Q: What is the most common bottleneck in microbial terpenoid production? A: The most frequent bottleneck is the limited supply of the universal precursors, IPP and DMAPP. This is often coupled with an imbalance in the metabolic flux, where central carbon metabolism does not adequately feed into the terpenoid biosynthetic pathways [22] [24].

Q: How can I improve the functional expression of plant cytochrome P450 enzymes in microbial hosts? A: S. cerevisiae is generally preferred over E. coli for reactions requiring P450s due to its eukaryotic machinery for proper protein folding, post-translational modification, and membrane integration. Strategies include codon-optimization, N-terminal engineering, and co-expression with compatible redox partners to facilitate electron transfer [24].

Q: What are the main strategies to reduce cytotoxicity of terpenoid intermediates? A: Key strategies include using two-phase fermentations with organic solvents (e.g., diisononyl phthalate) to extract the product in situ, and engineering subcellular compartmentalization in yeast or plant hosts to sequester toxic intermediates [23] [24].

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Terpenoid Production in Microbial Factories

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low product titer | Insufficient IPP/DMAPP supply; metabolic burden | Enhance precursor supply by overexpressing rate-limiting enzymes (e.g., HMGR, DXS); use dynamic regulatory circuits to balance gene expression [22] [23]. |

| Accumulation of toxic intermediates | Hydrophobic intermediates disrupt membranes | Implement a two-phase extraction system in the bioreactor; promote storage in lipid droplets; engineer pathways for less toxic intermediates [23] [24]. |

| Inefficient cyclization or functionalization | Poor expression or activity of terpene synthases/P450s | Employ enzyme engineering (directed evolution); use chaperone co-expression; select a more compatible microbial host (e.g., yeast for P450s) [22] [24]. |

| Genetic instability of engineered pathway | Toxicity of pathway genes or metabolites | Use genomic integration instead of plasmids; delete genes for proteases that may degrade heterologous enzymes [23]. |

Experimental Protocol: Enhancing Terpenoid Precursor Supply in E. coli

Objective: To engineer an E. coli strain with an amplified flux of carbon through the MEP pathway to boost the production of terpenoid precursors.

Materials:

- Strain: E. coli BL21(DE3) or other suitable production strain.

- Plasmids: Expression vectors containing genes for the MVA pathway (e.g., mvaS, mvaA) or key MEP pathway enzymes (e.g., dxs, idi, ispDF) under inducible promoters [24].

- Media: LB or defined minimal media (e.g., M9) with appropriate carbon sources (e.g., glycerol, which can be more effective than glucose for terpenoid production) [24].

- Antibiotics: For selective pressure.

Method:

- Strain Engineering: Clone and heterologously express the upper MVA pathway genes (mvaS, mvaA) in E. coli to augment the native MEP pathway. Alternatively, overexpress the rate-limiting enzyme 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS) of the MEP pathway [22] [24].

- Cultivation: Inoculate engineered strains in shake flasks with appropriate media and antibiotics. Grow at optimal temperature (e.g., 30-37°C).

- Pathway Induction: Once the culture reaches mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6-0.8), induce gene expression with a suitable inducer (e.g., IPTG).

- Product Analysis: After a suitable production period (e.g., 24-72 hours), extract metabolites and analyze IPP/DMAPP downstream products (e.g., limonene, amorphadiene) using GC-MS or LC-MS [24].

Machine Learning Applications

Machine learning models are being trained to predict the optimal combination of promoter strengths, gene copy numbers, and fermentation conditions to maximize flux through terpenoid pathways. AI tools also assist in the de novo design of terpene synthases with altered product specificity [25] [23].

Alkaloid Biosynthesis Pathway

Alkaloids are nitrogen-containing compounds with potent biological activities. Their biosynthetic origins are diverse, deriving from amino acids (e.g., tyrosine, tryptophan) or other pathways, such as polyketides. A well-studied example is the Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloid (BIA) pathway, which uses L-tyrosine as a precursor to produce compounds like morphine, codeine, and berberine [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Q: How can I identify unknown genes in a complex alkaloid pathway? A: Multi-omics integration is the most effective approach. Combine comparative transcriptomics (comparing gene expression in high- vs. low-producing tissues) with metabolomic profiling to identify co-expressed genes that correlate with metabolite abundance. This approach was successfully used to elucidate the early steps of diterpenoid alkaloid biosynthesis [27] [26].

Q: What is a major challenge in the heterologous production of alkaloids? A: The spatial organization of enzymes in metabolons (multi-enzyme complexes) in native plants is difficult to reconstitute in a heterologous host. This can lead to poor flux and the accumulation of intermediates [26] [28].

Q: Why is the reticuline intermediate so important? A: (S)-reticuline is a key branch-point intermediate in the BIA pathway. It serves as the substrate for multiple downstream pathways leading to different classes of alkaloids, including morphinans (e.g., morphine), protoberberines (e.g., berberine), and aporphines. Controlling its flux is critical for directing synthesis toward a specific target compound [26].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Alkaloid Biosynthesis

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete pathway reconstitution in yeast | Missing or inefficient enzymes; lack of metabolon formation | Screen enzyme orthologs from different plant sources for higher activity in the host; attempt to co-localize enzymes by creating synthetic protein scaffolds [26]. |

| Low yield of final product | Competition from branch pathways; poor transport between organelles | Use CRISPR-Cas9 to knock out competing pathway genes in the host; engineer subcellular targeting to optimize intermediate trafficking [23] [26]. |

| Difficulty elucidating late-stage pathway steps | Low abundance of enzymes and intermediates | Utilize virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) in the native plant; feed putative intermediate compounds to enzyme libraries and analyze products via LC-HRMS [27]. |

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Omic Elucidation of an Alkaloid Pathway

Objective: To identify candidate genes involved in a specific alkaloid's biosynthetic pathway.

Materials:

- Plant Materials: Tissues from different organs (root, stem, leaf) and/or different developmental stages of the medicinal plant.

- Reagents: Kits for RNA extraction, metabolome extraction, and next-generation sequencing.

Method:

- Sample Collection: Collect biological replicates from different tissues known to have varying alkaloid content.

- Multi-Omic Data Generation:

- Transcriptomics: Extract total RNA and perform RNA-seq to generate gene expression data.

- Metabolomics: Grind tissues in liquid nitrogen and extract metabolites using methanol/water solvents. Analyze alkaloid profiles using LC-MS/MS [26].

- Data Integration: Perform co-expression analysis. Correlate the expression levels of all genes with the abundance of your target alkaloid across all samples. Genes within the biosynthetic pathway will show a high positive correlation.

- Functional Characterization: Clone the top candidate genes and express them in a heterologous system (e.g., E. coli, yeast) or use in vitro enzyme assays to test their activity on predicted substrate molecules [27] [26].

Machine Learning Applications

ML models are applied to integrate transcriptomic and metabolomic datasets to predict gene-to-metabolite networks, significantly accelerating the discovery of novel alkaloid biosynthetic genes. AI also helps predict the substrate specificity of key enzymes like oxidoreductases and methyltransferases [25] [28].

Polyketide and Non-Ribosomal Peptide Biosynthesis

Polyketides (PKs) are synthesized by polyketide synthases (PKSs) that iteratively condense acyl-CoA building blocks (e.g., malonyl-CoA) in a manner analogous to fatty acid synthesis. Non-ribosomal peptides (NRPs) are assembled by non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) that incorporate proteinogenic and non-proteinogenic amino acids. Both systems often operate as modular assembly lines, where each module is responsible for one round of chain elongation and modification, leading to enormous structural diversity [29] [30].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Q: What is the biggest advantage of the assembly line logic of PKSs/NRPSs? A: The modular nature allows for combinatorial biosynthesis. By rationally swapping domains or modules between systems, researchers can engineer the production of novel "non-natural" natural products with potentially improved bioactivities [30].

Q: How can I rapidly identify the product of a cryptic biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC)? A: Use genome mining tools like antiSMASH to identify the BGC. Then, employ heterologous expression in a model host (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor) where the cluster's regulatory elements are replaced by strong, constitutive promoters to activate its expression [25] [31].

Q: Why is accurate prediction of PKS/NRP product structures from gene sequence still challenging? A: A significant challenge is the substrate promiscuity of adenylation (A) domains in NRPSs and the inaccurate prediction of β-carbon processing (e.g., reduction, dehydration) in PKS modules based on sequence alone [25] [30].

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for PKS and NRPS Engineering

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Cryptic or silent gene cluster | Tight transcriptional repression in native host | Heterologous expression in a well-characterized host; use CRISPRa to activate native promoters; co-culture with potential elicitor strains [25]. |

| Inactive or misfolded megasynthase | Improper folding of large, multi-domain proteins | Use chaperone co-expression; split the megasynthase into smaller, functional subunits; optimize cultivation temperature [31]. |

| Incorrect product structure prediction from sequence | Limitations of current bioinformatics tools | Employ advanced ML-based prediction tools (e.g., SANDPUMA for NRPs); verify structure experimentally through MS/MS and NMR spectroscopy [25] [30]. |

| Low titer in heterologous host | Incompatibility with host metabolism; lack of precursor building blocks | Engineer the host's supply of malonyl-CoA (for PKs) or specific amino acids (for NRPs); delete competing pathways [31]. |

Experimental Protocol: Genome Mining for Novel PKS/NRP Clusters

Objective: To computationally identify and characterize a novel polyketide or non-ribosomal peptide biosynthetic gene cluster from a microbial genome.

Materials:

- Hardware/Software: Computer with internet access.

- Input Data: A genomic sequence file (e.g., in FASTA format) of the target bacterium or fungus.

Method:

- BGC Identification: Submit your genomic sequence to the antiSMASH (Bacterial & Fungal Version) web server. This tool will identify and annotate all putative PKS, NRPS, and hybrid BGCs in the genome [25].

- Comparative Analysis: Use the BiG-FAM database to classify the identified BGC into a Gene Cluster Family (GCF), which groups together BGCs that are likely to produce structurally similar molecules [25].

- Detailed Annotation: Analyze the domain architecture of the PKS/NRPS genes using antiSMASH and related tools (e.g., NP.searcher) to predict the core scaffold structure, including colinearity between modules and the potential identity of incorporated building blocks [25].

- Prioritization: Cross-reference your findings with the MIBiG database to check if the cluster is known. Prioritize clusters that are unique or located in GCFs with known bioactive compounds for further experimental validation [25].

Machine Learning Applications

ML is transformative for PKS/NRPS research. Tools like NeuRiPP and SANDPUMA use neural networks and other ML algorithms to predict the substrate specificity of NRPS adenylation domains and the structures of final products directly from gene sequence data, moving beyond rule-based predictions [25].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Biosynthetic Pathway Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH [25] | Identifies & annotates biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) | Primary analysis of bacterial/fungal genomes for PKS, NRPS, Terpene, and other BGCs. |

| MIBiG Repository [25] | Database of known BGCs and their metabolites | Reference database to compare newly found BGCs against known ones. |

| pCRBlunt / pHZ1358 Vectors [31] | Cloning and gene replacement in Streptomyces | Genetic manipulation of actinomycetes, e.g., gene knockout in the argimycins P cluster. |

| S. cerevisiae Strain (e.g., CEN.PK2) | Eukaryotic microbial chassis for heterologous expression | Ideal host for pathways requiring cytochrome P450 enzymes (e.g., terpenoid oxidation, BIA biosynthesis) [23] [24]. |

| E. coli Strain (e.g., BL21(DE3)) | Prokaryotic microbial chassis for heterologous expression | Preferred host for rapid pathway prototyping and production of non-oxygenated terpenoids [24]. |

| LC-MS / GC-MS | Metabolite separation, identification, and quantification | Profiling and quantifying terpenoid, alkaloid, and polyketide production in engineered strains or plant extracts [31] [26] [24]. |

Visualizing Pathway Logic and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: A general workflow for biosynthetic pathway engineering, showing how machine learning (ML/AI) integrates with and optimizes each experimental stage.

Diagram 2: Core biosynthetic logic for terpenoids (MVA/MEP pathways) and benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIA pathway), highlighting key precursors and enzymes.

In biosynthetic pathway optimization, researchers traditionally rely on rule-based computational systems and manual curation approaches to design and analyze metabolic processes. While foundational, these methods present significant limitations that can hinder research progress. Rule-based systems operate on a fixed set of predefined "if-then" statements to automate decision-making, but they lack adaptability [32]. Manual curation involves experts reviewing and refining data by hand to ensure accuracy and completeness, a process that is highly resource-intensive [33]. This technical support article details the specific constraints of these traditional methods within machine learning-driven research, providing troubleshooting guidance to help scientists identify and overcome these challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary limitations of rule-based systems in pathway design?

Rule-based systems struggle with several key issues that limit their application in complex, dynamic research environments like biosynthetic pathway design.

- Adaptability and Learning: These systems cannot learn from experience or adapt to new, unforeseen situations. They are confined to their initial programming, making them unsuitable for dynamic conditions or for exploring novel pathway designs not already encoded in their rules [32] [34].

- Handling Complexity and Ambiguity: They often have difficulty processing uncertain or ambiguous information, which can lead to inaccurate decisions. Biological systems are inherently complex and sometimes unpredictable, a scenario that rule-based systems are poorly equipped to handle [32].

- Scalability and Maintenance: As research scope expands, managing a large number of rules becomes complex and challenging. Performance can slow down, and the likelihood of conflicts between rules increases, making the system difficult to maintain and update [32] [34].

Q2: What specific challenges does manual curation present in biomedicine?

Manual curation, while considered a "gold standard" for accuracy, introduces significant practical bottlenecks in the era of big data [35] [33].

- Scale and Volume: The amount of biological data is doubling approximately every two years. Manually curating the vast datasets generated by high-throughput technologies is time-consuming and often impractical, leading to major delays in research timelines [33].

- Subjectivity and Bias: The process introduces human subjectivity, as different curators may interpret and annotate data differently. This can lead to inconsistencies and biases in the curated datasets, affecting the reliability of downstream analyses [33].

- Resource Intensiveness: Manual curation requires highly skilled experts, making it a costly and resource-intensive process. It diverts valuable expert time from strategic analysis to repetitive data processing tasks [33].

Q3: Are there quantitative comparisons of manual versus automated curation efficiency?

Yes. Studies have demonstrated a dramatic difference in efficiency. For instance, manually curating a single dataset of approximately 50-60 samples—including locating publications, extracting metadata, and documenting all fields—can take 2-3 hours. In contrast, an efficient automated curation process, even with an expert double-checking each step, can complete the same task in just 2-3 minutes per dataset [33]. This represents a potential ~60x acceleration in the curation process, which is critical for scalability.

Q4: How do rule-based systems compare to modern deep learning approaches in performance?

Deep learning models have been shown to significantly outperform traditional rule-based systems in biosynthetic prediction tasks. The table below summarizes a comparative evaluation from a study on bio-retrosynthesis:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Bio-retrosynthesis Models

| Model Type | Top-1 Accuracy (%) | Top-10 Accuracy (%) | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rule-based Model (RetropathRL) | 19.2 | 42.1 | Relies on pre-defined, expert-authored reaction rules [2]. |

| Deep Learning Model (BioNavi-NP) | 21.7 | 60.6 | Learns patterns directly from data using transformer neural networks [2]. |

The deep learning model was 1.7 times more accurate than the conventional rule-based approach in recovering reported building blocks for a set of test compounds [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inability to Propose Novel Biosynthetic Pathways

Issue: Your rule-based system fails to propose pathways for compounds that are not explicitly covered in its existing knowledge base.

Explanation: Rule-based systems are inherently limited by their predefined rules. If a novel compound or reaction sequence is not described by these rules, the system cannot propose it [2]. They lack the generalization capability to "reason" about new scenarios.

Solution:

- Confirm Rule Coverage: Check if the target compound or similar structural motifs are represented in the system's rule set. This will confirm the system's inherent limitation.

- Transition to a Data-Driven Model: Adopt a deep learning-based tool like BioNavi-NP [2]. These models are trained on vast reaction databases and can predict plausible biosynthetic pathways for compounds outside their immediate training set by learning underlying chemical transformation patterns.

- Utilize a Hybrid Approach: Use a rule-based system for initial filtering or to handle well-established pathways, and integrate it with a machine learning model to explore novel route possibilities.

Problem: Manual Curation Bottlenecks Slowing Down Research

Issue: The manual process of data curation is creating a significant bottleneck, preventing your team from analyzing data at the required scale and speed.

Explanation: The sheer volume and heterogeneity of modern biological data make manual curation a limiting factor. It is labor-intensive, slow, and difficult to scale [35] [33].

Solution:

- Implement Automated Curation Tools: Leverage platforms that use machine learning and AI to automate the repetitive stages of curation, such as data ingestion, standardization, and harmonization [33].

- Adopt a Human-in-the-Loop Model: Integrate automated systems with human expertise. Allow the automated tool to process the bulk of the data rapidly, while human experts validate results, handle complex edge cases, and provide high-level quality control. This model combines the speed of automation with the accuracy of expert knowledge [33].

- Define Clear Data Standards: To improve the effectiveness of both manual and automated curation, establish and enforce standard nomenclature (e.g., HGVS for genetic variants [35]) and data formats from the beginning of your projects.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Evaluating a New Pathway Design Tool

Objective: To systematically assess whether a new deep learning-based pathway design tool offers a significant advantage over a traditional rule-based system.

Methodology:

- Benchmark Set Selection: Curate a set of 50-100 natural products with known, well-characterized biosynthetic pathways.

- Tool Execution:

- Performance Metrics:

- Accuracy: Measure the percentage of pathways where the tool correctly identified the known building blocks (Top-1 and Top-10 accuracy) [2].

- Novelty: Record the number of plausible alternative pathways proposed by each tool that are not in the standard database, to be reviewed by an expert.

- Computational Time: Record the time taken by each system to generate predictions for the entire benchmark set.

- Data Analysis: Compare the results using a table like the one below to guide tool selection.

Table 2: Tool Evaluation Summary

| Evaluation Metric | Rule-Based System | Deep Learning System | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-10 Accuracy | 42.1% | 60.6% | DL system is more accurate [2]. |

| Novel Pathway Suggestions | Low | High | DL system better for novel discovery. |

| Execution Speed | Fast | Variable (can be fast) | Rule-based may be faster for simple queries. |

| Ease of Updating | Difficult (manual rule addition) | Easy (retrain with new data) | DL system is more maintainable. |

Workflow: Transitioning from Manual to Automated-Hybrid Curation

The following diagram illustrates the recommended workflow for integrating automation into data curation to overcome the limitations of a purely manual process.

Diagram: Hybrid Curation Workflow with Automation

Table 3: Essential Databases for Biosynthetic Pathway Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| PubChem [5] | Compound Database | Provides chemical structures, properties, and biological activities for millions of compounds, serving as a foundational resource. |

| KEGG [5] [2] | Pathway Database | A comprehensive resource integrating genomic, chemical, and systemic functional information, including known metabolic pathways. |

| MetaCyc [5] [2] | Pathway Database | A curated database of metabolic pathways and enzymes from various organisms, valuable for studying metabolic diversity. |

| UniProt [5] | Protein Database | Provides detailed, curated information on protein sequences, functions, and enzyme classifications. |

| BRENDA [5] | Enzyme Database | The main enzyme information system, providing functional data on enzymes isolated from thousands of organisms. |

| BioNavi-NP [2] | Software Tool | A deep learning toolkit for predicting biosynthetic pathways of natural products, surpassing rule-based limitations. |

AI in Action: Deep Learning Models, Automated Platforms, and Practical Implementation

Technical Support & Troubleshooting

This section addresses common technical challenges and frequently asked questions for researchers using deep learning models for retrobiosynthesis prediction.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the key difference between template-based and template-free models for bio-retrosynthesis, and why are template-free models like transformers often preferred?

Template-based methods rely on a pre-defined database of biochemical reaction rules or templates. They match the target molecule to these templates to propose precursors. Their major limitation is an inability to predict novel transformations not already in their database [2]. In contrast, template-free models, such as the GSETransformer or BioNavi-NP, use deep learning to predict retrosynthetic steps without pre-defined rules. They learn reaction patterns directly from data and can therefore propose novel, non-native biosynthetic pathways, making them better suited for exploring the complex space of natural product biosynthesis [36] [2].

Q2: My model performs well on benchmark datasets like USPTO-50K but fails to predict plausible biosynthetic pathways for my target natural product. What could be the cause?

This is a common issue stemming from the domain gap between general organic reactions and specialized biosynthesis. Models trained solely on organic reactions (e.g., USPTO-50K) learn general chemistry but lack knowledge of enzyme-catalyzed biosynthesis-specific transformations [2]. To fix this:

- Use a Domain-Specific Model: Employ models specifically trained or fine-tuned on biochemical reaction datasets like BioChem Plus [36].

- Data Augmentation: As demonstrated with BioNavi-NP, augmenting biochemical training data with NP-like organic reactions (USPTO_NPL) can significantly boost performance by providing broader chemical context while retaining a focus on relevant structures [2].

Q3: How can I improve the low accuracy of my single-step retrosynthesis predictions?

Several strategies proven in state-of-the-art models can enhance accuracy:

- Data Augmentation: Use SMILES augmentation, which generates multiple valid string representations of the same molecule, to enrich the training data and improve model robustness [36].

- Model Ensembling: Combine predictions from multiple models (e.g., with different random initializations). BioNavi-NP used this to increase top-1 accuracy from 17.2% to 21.7% [2].

- Architecture Enhancement: Integrate different molecular representations. The GSETransformer, for example, merges graph neural networks (capturing molecular topology) with sequence-based transformers, leading to superior performance [36].

Q4: Multi-step pathway planning is computationally expensive and slow. Are there efficient search algorithms for this task?

Yes, traditional search methods like Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) are inefficient for the high-branching complexity of biosynthetic pathways. The AND-OR tree-based search algorithm (as used in BioNavi-NP) is a more efficient alternative. It navigates the combinatorial search space more effectively, rapidly identifying optimal multi-step routes from simple building blocks to the target NP [2].

Q5: What are the best practices for preparing and curating data for training a retrobiosynthesis model?

- Chirality Matters: Including stereochemical information in reaction SMILES is critical. Removing chirality was shown to decrease the top-10 accuracy of a model from 27.8% to 16.3% [2].

- Atom Mapping: For biochemical reactions that are not atom-mapped, use tools like RXNMapper, a neural-network-based model, to generate reliable atom mappings for training data [36].

- Data Curation: Rely on curated databases like MetaCyc, KEGG, and Rhea for high-quality biochemical reaction data [5].

Performance Benchmarking and Model Comparison

The table below summarizes the performance of key models on standard benchmarks, providing a reference for expected outcomes.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Models on Retrosynthesis Prediction

| Model | Architecture | Key Feature | Training Dataset(s) | Top-1 Accuracy | Top-10 Accuracy | Key Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSETransformer | Hybrid Graph-Sequence Transformer | Integrates GNN and SMILES | USPTO-50K, BioChem Plus | State-of-the-art on benchmarks [36] | State-of-the-art on benchmarks [36] | Superior performance on single- and multi-step tasks [36] |

| BioNavi-NP | Transformer Neural Network | AND-OR tree search for multi-step | BioChem, USPTO_NPL (augmented) | 21.7% (ensemble) [2] | 60.6% (ensemble) [2] | Identified pathways for 90.2% of test NPs [2] |

| RetroPathRL (Rule-based) | Reinforcement Learning | Pre-defined reaction rules | Biochemical rules | 10.6% [2] | 42.1% [2] | Baseline for rule-based performance [2] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing and evaluating deep learning models for retrobiosynthesis.

Protocol: Training a Robust Single-Step Prediction Model

Objective: Train a transformer model to predict candidate precursors for a target product molecule in a single retrosynthetic step.

Materials:

- Hardware: High-performance computing node with modern GPU (e.g., NVIDIA A100/V100).

- Software: Python 3.8+, PyTorch or TensorFlow, RDKit, Transformer library (e.g., Hugging Face).

- Data: Curated dataset of reaction SMILES (e.g., BioChem, USPTO-50K).

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Source Data: Obtain biochemical reactions from MetaCyc, KEGG, or MetaNetX [36] [5]. For organic reactions, use USPTO [2].

- Preprocessing: Canonicalize SMILES using RDKit. Ensure atom mapping is consistent; use RXNMapper if needed [36].

- Data Splitting: Split data randomly into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) sets, ensuring no data leakage [36].

- Data Augmentation:

- SMILES Augmentation: For each molecule in the training set, generate multiple equivalent SMILES strings by altering the initial encoding atom [36] [2].

- Root Alignment (for reactions): For a product molecule, randomly select a root atom to generate its SMILES. Identify the corresponding root atom in the reactants to create a root-aligned input-output pair. This reduces model complexity and strengthens cross-attention [36].

- Transfer Learning: Augment a specialized biochemical dataset (e.g., BioChem) with a larger dataset of NP-like organic reactions (e.g., USPTO_NPL) to improve model robustness and general patterns [2].

- Model Training:

- Architecture: Implement a standard encoder-decoder Transformer model.

- Training Loop: Train the model to predict reactant SMILES from product SMILES.

- Ensembling: Train multiple models with different random seeds and average their predictions to boost accuracy and robustness [2].

- Model Evaluation:

- Metrics: Calculate top-(n) accuracy ((n)=1, 3, 5, 10). A prediction is correct if the set of predicted precursors exactly matches the ground truth [2].

- Validation: Use the validation set for hyperparameter tuning and early stopping. Report final performance on the held-out test set.

Diagram 1: Single-step model training workflow.

Protocol: Multi-Step Biosynthetic Pathway Planning with AND-OR Tree Search

Objective: Automatically identify a complete biosynthetic route from simple, purchasable building blocks to a target natural product.

Materials:

- A trained and validated single-step retrosynthesis model (from Protocol 2.1).

- A list of available building blocks (e.g., amino acids, common metabolic intermediates).

Procedure:

- Tree Initialization: Create a root node representing the target natural product.

- Node Expansion:

- For a given molecule (node), use the single-step model to generate a list of top-(k) candidate precursor sets.

- Each candidate set becomes a child node. If a set contains multiple molecules, it forms an AND node (all precursors are required). Different candidate sets are OR nodes (alternative routes).

- Cost Heuristic: Assign a cost to each molecule, typically based on its complexity or commercial availability. Simple building blocks have low cost.

- Search and Selection:

- The algorithm navigates the AND-OR tree, prioritizing the expansion of nodes that minimize the total estimated cost of the pathway.

- It recursively expands nodes until all leaf nodes are available building blocks or a specified depth limit is reached.

- Pathway Validation: The proposed pathways should be checked for biochemical plausibility, and enzyme compatibility can be evaluated using tools like Selenzyme [2].

Diagram 2: AND-OR tree-based multi-step planning logic.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Retrobiosynthesis

| Category | Item / Resource | Function / Description | Key Databases / Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | Biochemical Reaction Databases | Provide curated, enzyme-catalyzed reactions for model training and validation. | MetaCyc [5], KEGG [5], Rhea [5] |

| Organic Reaction Databases | Provide large-scale general chemical reactions for data augmentation. | USPTO [36] [2] | |

| Compound Databases | Provide structural and bioactivity information for reactants and products. | PubChem [5], ChEBI [5], NPAtlas [5] | |

| Software & Models | Retrobiosynthesis Platforms | End-to-end tools for predicting single- and multi-step biosynthetic pathways. | BioNavi-NP [2], GSETransformer [36] |

| Cheminformatics Toolkits | Process and manipulate molecular structures (SMILES, graphs). | RDKit | |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Build, train, and deploy transformer and graph neural network models. | PyTorch, TensorFlow | |

| Validation Tools | Enzyme Prediction Tools | Recommend plausible enzymes for a predicted biochemical reaction step. | Selenzyme [2], E-zyme2 [2] |

| Atom Mapper | Automatically generates atom mapping for biochemical reactions. | RXNMapper [36] |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My novoStoic2.0-generated pathway has a highly negative overall Gibbs free energy (ΔG'°), yet the in vivo yield is very low. What could be the cause? A1: A highly negative ΔG'° suggests thermodynamic feasibility, but low yield often points to kinetic or regulatory bottlenecks. Common causes include:

- Enzyme Kinetics: One or more enzymes in the pathway may have low catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) for your chosen substrates, creating a rate-limiting step.

- Metabolite Toxicity: An intermediate metabolite may be toxic to the host organism, inhibiting growth and product formation.

- Cofactor Imbalance: The pathway may disproportionately consume or regenerate cofactors (e.g., NADH/NAD+, ATP/ADP), creating an imbalance that halts flux.

- Poor Enzyme Expression: The selected heterologous enzymes may not express well or form insoluble aggregates in your host.

Q2: How does the machine learning component in novoStoic2.0 improve upon previous rule-based pathway prediction tools? A2: Traditional tools rely on pre-defined reaction rules, which can miss novel biotransformations. The ML component in novoStoic2.0 is trained on vast biochemical databases and can:

- Predict Novel Enzymes: Suggest non-canonical enzymes or enzyme variants for a given reaction, expanding the solution space.

- Predict Kinetic Parameters: Estimate kcat and KM values for proposed enzyme-substrate pairs, providing a preliminary kinetic assessment.

- Rank Pathways Holistically: Integrate thermodynamic, kinetic, and host-specific expression data to rank pathways by their predicted efficiency, rather than just thermodynamic favorability.

Q3: What is the difference between "Standard" and "In Vivo" Gibbs free energy in the platform's output, and which one should I prioritize? A3:

- Standard Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG'°): Calculated at standard conditions (1 M concentration, pH 7.0). It is a useful constant for initial screening.

- In Vivo Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG'): Calculated using estimated intracellular metabolite concentrations. This provides a more physiologically relevant assessment of thermodynamic feasibility.

You should prioritize pathways where the In Vivo ΔG' is sufficiently negative for all steps. A negative ΔG'° but positive ΔG' indicates a step is thermodynamically blocked under physiological conditions.

Q4: The enzyme recommended by the platform is not available in my preferred expression vector. What are my options? A4:

- Ortholog Search: Use the platform's ortholog finder to identify homologous enzymes from different organisms that may be available in your desired vector system.

- Gene Synthesis: Synthesize the gene codon-optimized for your host and clone it into your preferred vector.

- Check Repository: Verify the enzyme's availability in standard repositories like Addgene or the DNASU Plasmid Repository.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Failure in Pathway Expansion Step Symptoms: The platform returns no or very few pathway suggestions for your target compound. Resolution Steps:

- Verify Target Compound: Ensure your target compound is in a recognizable format (e.g., InChI Key, SMILES).

- Check Reaction Database: Confirm that the underlying reaction database (e.g., KEGG, MetaCyc) is online and accessible.

- Adjust Parameters: Widen the search parameters:

- Increase the maximum number of reaction steps.

- Allow for more than one putative reaction step.

- Include less-specific enzyme classes (EC numbers) in the search.

Issue: Thermodynamic Infeasibility Flag Symptoms: The platform flags one or more steps in a proposed pathway as thermodynamically infeasible (ΔG' > 0). Resolution Steps:

- Review Metabolite Concentrations: Check the estimated in vivo concentrations for the reactants and products of the infeasible step. The estimation might be inaccurate.

- Identify the "Uphill" Step: Pinpoint the specific reaction. Common culprits are carboxylations, dehydrations, or reactions involving ATP hydrolysis without a clear coupling mechanism.

- Explore Enzyme Engineering: Consider using the platform's ML suggestions to find enzyme variants with higher activity that could drive the reaction.

- Pathway Bypass: Look for an alternative, thermodynamically favorable reaction sequence that bypasses the problematic step.

Issue: Low Product Titer in Experimental Validation Symptoms: The pathway expresses in the host but produces negligible amounts of the target product. Resolution Steps:

- Confirm Gene Expression: Use SDS-PAGE or RT-qPCR to verify that all pathway enzymes are being expressed.

- Measure Intermediate Metabolites: Use LC-MS/MS to track intermediate accumulation, which can identify a specific bottleneck reaction.

- Cofactor Analysis: Measure intracellular levels of key cofactors (NAD(P)H, ATP). Imbalances can be addressed by introducing cofactor recycling systems.

- Promoter/ RBS Tuning: Systematically vary the strength of promoters and ribosome binding sites (RBS) to optimize the expression balance of all pathway enzymes.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: In Silico Pathway Design and Thermodynamic Evaluation using novoStoic2.0

Methodology:

- Input: Define the target compound using its SMILES string or InChI Key.

- Pathway Expansion: Execute the graph-based search algorithm to enumerate all possible biochemical pathways from a set of core metabolites to the target.

- Thermodynamic Evaluation: a. Retrieve standard Gibbs free energy of formation (ΔfG'°) for all compounds from the component contribution method. b. Calculate the standard reaction Gibbs free energy (ΔrG'°) for each reaction step. c. Estimate in vivo metabolite concentrations (if available) to calculate the in vivo ΔrG'.

- Enzyme Selection: Use the integrated ML model to suggest candidate enzymes (with predicted kinetic parameters) for each reaction step and rank pathways based on a composite score of thermodynamics, kinetics, and host compatibility.

Table 1: Comparison of Pathway Metrics for Target Compound "X"

| Pathway ID | Number of Steps | Overall ΔG'° (kJ/mol) | Bottleneck Step (ΔG'°) | ML-Predicted Flux Score | Recommended Host |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PX-001 | 4 | -85.2 | R2: -5.1 | 0.89 | E. coli |

| PX-002 | 5 | -92.7 | R4: +3.2* | 0.45 | S. cerevisiae |

| PX-003 | 4 | -78.5 | R1: -10.5 | 0.91 | E. coli |

*Flagged as thermodynamically infeasible under standard conditions.

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of a Predicted Pathway in a Microbial Host

Methodology:

- Strain Engineering: Clone the genes encoding the selected enzymes into a compatible expression vector(s) and transform into your microbial host (e.g., E. coli BL21(DE3)).

- Cultivation: Grow the engineered strain in a defined medium with the required precursors.

- Metabolite Extraction: Harvest cells at mid-log phase and perform a quenching extraction (e.g., using cold methanol/water) for intracellular metabolite analysis.