Harnessing CFD Simulation to Optimize Bioreactor Gradients for Advanced Cell Culture and Bioprocessing

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation for analyzing and optimizing gradients in bioreactors.

Harnessing CFD Simulation to Optimize Bioreactor Gradients for Advanced Cell Culture and Bioprocessing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation for analyzing and optimizing gradients in bioreactors. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of fluid dynamics and mixing phenomena, detail step-by-step methodologies for setting up and running effective CFD simulations, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and discuss critical validation techniques. By integrating these four perspectives, the article demonstrates how CFD-driven gradient analysis enhances control over critical process parameters (pH, nutrients, dissolved oxygen, shear stress), directly impacting cell viability, product yield, and biomanufacturing scalability for therapeutics like monoclonal antibodies and cell therapies.

Understanding Bioreactor Gradients: Why Homogeneity is the Enemy of Scalable Cell Culture

Within the controlled environment of a bioreactor, the assumption of homogeneity is a foundational but often flawed ideal. Gradients—spatial variations in critical process parameters—are inherent to all bioreactor systems, posing significant challenges and opportunities in bioprocessing. This whitepaper, framed within the context of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation for bioreactor gradient analysis research, defines the nature of these gradients, elucidates their profound impact on cell culture and microbial fermentation, and underscores the necessity of their quantification and control for robust process development and scale-up.

The Nature of Bioreactor Gradients

Gradients arise from the imperfect mixing of vessel contents. While agitation and sparging aim to create a uniform environment, local variations persist. These gradients are dynamic, fluctuating with process conditions, scale, and cell metabolism. The primary gradients of concern are:

- Concentration Gradients: Uneven distribution of substrates (e.g., glucose, glutamine), dissolved gases (O₂, CO₂), metabolites (e.g., lactate, ammonium), and secreted products.

- Physical Gradients: Variations in local fluid shear stress, energy dissipation rate, and pressure, particularly near the impeller or sparger.

These gradients create a heterogeneous environment where cells experience different conditions depending on their momentary location in the vessel, leading to population heterogeneity.

The Impact of Gradients: From Cellular Physiology to Process Performance

Gradients are not merely engineering curiosities; they directly influence biology and process outcomes. Their effects cascade from the cellular to the production scale.

Dissolved Oxygen (DO) and Carbon Dioxide (pCO₂) Gradients

Oxygen is a critical, poorly soluble substrate, while CO₂ is a metabolic byproduct. Their gradients are often the most severe.

- Hypoxic Zones: Cells circulating through low-DO regions experience oxygen limitation, shifting metabolism towards anaerobic pathways (e.g., increased lactate production). This alters growth, productivity, and product quality.

- pCO₂ Accumulation: High local pCO₂ can acidify the intracellular environment, inhibit cell growth and specific productivity, and impact glycosylation patterns of therapeutic proteins.

Nutrient and Metabolite Gradients

- Feast-Famine Cycles: Cells passing through a high-glucose zone may exhibit rapid uptake and overflow metabolism, followed by starvation in nutrient-poor zones. This dynamic stress can impact viability and titer.

- Inhibitory Metabolites: Local accumulation of waste products like lactate or ammonium can inhibit growth and productivity in specific vessel regions before bulk concentrations become critical.

Shear Stress Gradients

The energy input is highly non-uniform. Cells near the impeller tip experience brief, intense hydrodynamic forces (eddies, jets) that can damage cells or trigger protective signaling pathways, while cells in quieter regions do not.

Table 1: Impact of Key Gradients on Bioprocess Outcomes

| Gradient Type | Primary Cause | Potential Cellular Impact | Observed Process Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved O₂ | Consumption rate > Supply rate (Mass transfer limitation) | Metabolic shift; Oxidative stress; Apoptosis | Reduced growth rate; Altered metabolite profile; Changed product quality (e.g., glycosylation) |

| Dissolved CO₂ | Production rate > Stripping rate | Intracellular acidification; Enzyme inhibition | Reduced specific productivity; Altered product quality attributes |

| Nutrient (e.g., Glucose) | Consumption > Convective supply | Metabolic oscillation; Stress response | Population heterogeneity; Reduced overall yield |

| Shear Stress | Local energy dissipation (ε) | Cell damage; Mechanical stimulation; Signaling changes | Reduced viability; Altered morphology; Changed aggregation behavior |

The Role of CFD in Gradient Analysis

Empirical measurement of gradients at production scale is nearly impossible due to sensor intrusion and limited spatial resolution. This is where CFD simulation becomes an indispensable research tool. CFD solves the fundamental equations of fluid flow (Navier-Stokes), mass transfer, and reaction kinetics to predict the three-dimensional, time-dependent fields of velocity, species concentration, and shear stress within a bioreactor.

- Virtual Prototyping: Test impeller configurations, sparger designs, and operating conditions (agitation, gassing rates) in silico before physical builds.

- Scale-Down Modeling: Design small-scale vessels that accurately replicate the gradient environment (e.g., fluctuating DO/pCO₂) of large-scale reactors, enabling meaningful process characterization.

- Root-Cause Analysis: Diagnose the origin of scale-up failures or lot-to-lot variability by linking process data to predicted gradient severity.

The core thesis of modern bioprocess development is that integrating CFD-based gradient analysis with cell biology knowledge is essential for predictive scale-up and consistent product quality.

Experimental Protocols for Gradient Validation & Study

CFD models require validation, and gradient effects must be studied biologically. Key methodologies include:

Protocol 1: Microscale Gradient Mimicry in Multi-Well Plates

- Objective: To study the biological response of cells to controlled, oscillating concentrations of O₂ or nutrients, simulating passage through gradients.

- Methodology:

- Utilize programmable bioreactor systems or specialized plates housed in controlled gas chambers.

- Define a cycling profile (e.g., DO cycling between 10% and 80% saturation with a 30-second period) based on CFD predictions for a large-scale vessel.

- Inoculate cells and run the cycling protocol in parallel with a constant control culture.

- Monitor metabolites (e.g., lactate, ammonium), viability, growth, and productivity.

- Harvest for -omics analysis (transcriptomics, proteomics) to identify stress pathways induced by cycling.

Protocol 2: Tracer-Based Mixing Time Characterization

- Objective: To experimentally measure mixing efficiency and validate CFD flow field predictions.

- Methodology:

- Equip the bioreactor with a pH or conductivity probe.

- Under non-growth conditions (cell-free media, typical operating conditions), inject a bolus of a tracer (e.g., acid/base for pH, salt for conductivity) at a predicted poorly mixed zone.

- Record the probe response over time. The mixing time is defined as the time to reach 95% of the final uniform signal.

- Compare the experimental mixing time and curve shape to the CFD-predicted tracer dispersion.

Protocol 3: Local Sampling for Metabolite/Gas Analysis

- Objective: To obtain spatial concentration data for CFD model validation (typically at pilot scale).

- Methodology:

- Install multiple sample ports at strategic locations (near impeller, below surface, near walls).

- Using a rapid, isokinetic sampling device, withdraw small, simultaneous samples from multiple ports during active fermentation.

- Immediately analyze samples for key metabolites (glucose, lactate), dissolved gases (via blood gas analyzer for O₂, CO₂), and pH.

- Map the measured concentrations against CFD-predicted concentration fields.

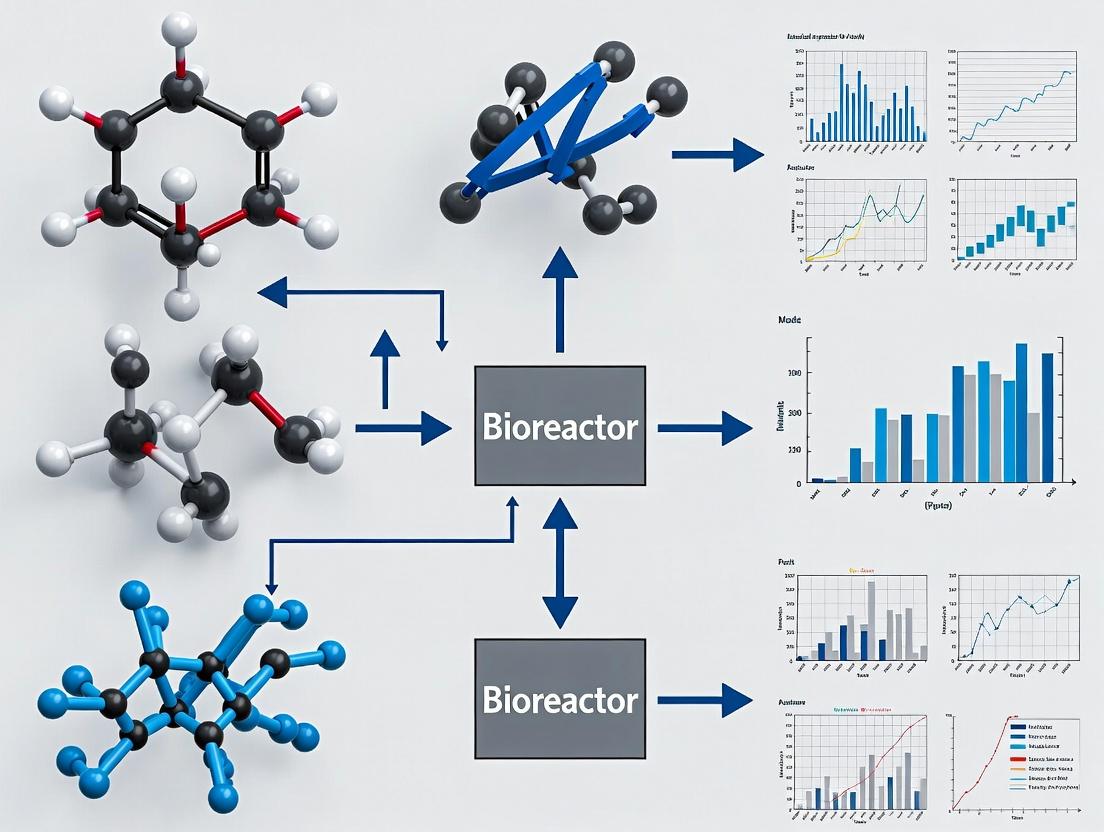

Diagram: The CFD-Driven Bioreactor Optimization Workflow

Title: CFD-Driven Workflow for Bioreactor Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Gradient Analysis Research

| Item | Function & Relevance to Gradient Studies |

|---|---|

| Fluorescent/Optical DO Probes (e.g., Ruthenium-based) | Enable non-invasive, real-time measurement of dissolved oxygen concentration at small scale or in specialized equipment, crucial for validating DO dynamics. |

| Rapid Sampling Devices (Isokinetic probes) | Allow withdrawal of small-volume samples from specific bioreactor locations without disrupting flow, enabling spatial metabolite/gas analysis for CFD validation. |

| Programmable Bioreactor Systems (Bench-top with gas mixing) | Permit precise control and oscillation of inlet gas composition (O₂, N₂, CO₂) to mimic large-scale dissolved gas gradients in scale-down models. |

| Shear-Sensitive Reporter Cell Lines | Engineered cells expressing a fluorescent protein under the control of a shear-responsive promoter (e.g., COX-2) to visualize and quantify cellular response to shear gradients. |

| Metabolomics Kits (for Glucose, Lactate, Ammonium) | Provide rapid, high-throughput analysis of metabolite concentrations from many small-volume samples taken during spatial or temporal gradient studies. |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software (e.g., ANSYS Fluent, COMSOL) | The core in silico tool for simulating fluid flow, mass transfer, and reactions to predict gradients and optimize bioreactor design and operation. |

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has become an indispensable tool for the design and optimization of bioreactors by simulating the complex interplay between fluid flow, mass transfer, and cellular kinetics. A critical challenge in bioreactor scale-up and performance is the formation of physical and chemical gradients, which deviate from the idealized well-mixed assumption. This whitepaper examines four key gradient parameters—Dissolved Oxygen (DO), pH, Nutrients, and Waste Metabolites—within the context of CFD-driven bioreactor analysis. Understanding and modeling these gradients is paramount for predicting cell behavior, ensuring product consistency, and translating laboratory-scale processes to industrial manufacturing, particularly in the biopharmaceutical sector.

In-Depth Analysis of Key Gradient Parameters

Dissolved Oxygen (DO)

DO is a critical parameter for aerobic cultures. Gradients form due to oxygen consumption by cells and limited mass transfer from sparged gas bubbles. Low DO can lead to hypoxia, altering cellular metabolism and productivity, while excessively high DO can be cytotoxic.

Key Quantitative Data: Table 1: Dissolved Oxygen (DO) Parameters in Mammalian Cell Culture

| Parameter | Typical Range | Critical Low Threshold | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Setpoint | 20-50% air saturation | 10-20% air saturation | Varies by cell line & process phase |

| Oxygen Uptake Rate (OUR) | 0.05-0.5 mmol/L/h | - | Higher in high-density cultures |

| Mass Transfer Coefficient (kLa) | 2-20 h⁻¹ | - | Design target for scale-up |

| Solubility (in water, 37°C) | ~0.2 mmol/L at 1 atm | - | Strong function of temperature & salinity |

pH

pH gradients arise from the accumulation of acidic waste products (e.g., lactate, CO₂) or basic metabolites and the consumption of buffering agents. Local pH shifts can dramatically affect enzyme activity, membrane potential, and product stability.

Key Quantitative Data: Table 2: pH Parameters in Mammalian Cell Culture

| Parameter | Typical Range | Optimal Range | Control Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture pH | 6.8 - 7.4 | 7.0 - 7.2 | CO₂ sparging & base addition (e.g., Na₂CO₃) |

| Lactate Production Rate | 0.1-1.0 g/L/day | - | Can shift to consumption in later phases |

| pCO₂ in Bioreactor | 40 - 150 mmHg | < 120 mmHg | Impacts osmolarity & pH |

Nutrients

Gradients of essential nutrients (e.g., glucose, glutamine, amino acids) form due to convective-diffusive transport limitations and local consumption. Depletion zones can trigger nutrient starvation, shifting metabolism and impacting cell growth and viability.

Key Quantitative Data: Table 3: Key Nutrient Parameters

| Nutrient | Typical Initial Concentration (mM) | Critical Depletion Threshold (mM) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 15-25 mM (∼3-5 g/L) | ~0.5 mM | Energy (glycolysis) & biosynthesis |

| Glutamine | 2-6 mM | ~0.2 mM | Energy (TCA) & nitrogen source |

| Essential Amino Acids | Variable, 0.1-2 mM | Nanomolar range | Protein synthesis |

Waste Metabolites

Metabolic by-products like lactate and ammonium accumulate, forming positive concentration gradients from the cell cluster outward. These compounds can inhibit cell growth and product formation.

Key Quantitative Data: Table 4: Inhibitory Waste Metabolites

| Metabolite | Typical Accumulation Range | Inhibitory Threshold | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate | 0 - 50 mM | > 20-30 mM | Inhibits cell growth, lowers pH |

| Ammonium (NH₄⁺) | 0 - 5 mM | > 2-3 mM | Alters glycosylation, inhibits growth |

Experimental Protocols for Gradient Measurement

Protocol 1: Microsensor Profiling for Local DO and pH

- Objective: To measure point gradients within a bioreactor at micro-scale.

- Materials: Clark-type oxygen microsensor, pH microelectrode, 3-axis micromanipulator, data acquisition system, bench-top bioreactor.

- Method:

- Calibrate microsensors in sterile buffer under standard conditions (DO: zero and air saturation; pH: 4.0, 7.0, 10.0 buffers).

- Aseptically insert sensors into the bioreactor via sealed ports.

- Using the micromanipulator, position the sensor tip at a reference point (e.g., near the impeller).

- Move the sensor in precise increments (e.g., 100 µm) towards a stagnant zone or cell aggregate.

- Record steady-state DO/pH readings at each position.

- Repeat across different radial and axial locations to build a 2D/3D map.

Protocol 2: Sampled Zone Analysis for Nutrients and Metabolites

- Objective: To measure macroscopic gradients by analyzing batch samples from distinct reactor zones.

- Materials: Multi-port sampling device (e.g., a "Lollipop" sampler), micro-syringes, bioanalyzer (e.g., Cedex Bio, Nova BioProfile).

- Method:

- Install a sampler with multiple intlets positioned at critical locations (top, middle, bottom, near sparger, near walls).

- At a given time point, simultaneously withdraw small volume samples (∼200 µL) from each inlet.

- Immediately analyze samples for glucose, glutamine, lactate, ammonium, and pH using the bioanalyzer.

- Correlate concentration data with spatial coordinates of the sample ports.

Integration with CFD Simulation: Pathways and Workflow

CFD-Based Gradient Analysis Workflow

Cell Signaling Responses to Key Gradients

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Reagents & Materials for Gradient Studies

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Fluorescent DO Sensor Particles (e.g., Pt(II)-porphyrin based) | For 2D/3D optical mapping of dissolved oxygen gradients in transparent systems. |

| pH-Sensitive Fluorophores (e.g., SNARF, BCECF) | For non-invasive, spatially resolved pH measurement via fluorescence microscopy or spectroscopy. |

| Bioanalyzer & Assay Kits (e.g., BioProfile FLEX, Cedex Bio) | For rapid, automated quantification of metabolites (glucose, lactate, glutamine, ammonium) and gases in micro-samples. |

| Microsensors (DO, pH, NH4+) | For high-resolution (<50 µm) point measurements within dense cell cultures or aggregates. |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software (e.g., ANSYS Fluent, COMSOL) | To simulate fluid flow, mass transfer, and gradient formation for bioreactor analysis and scale-up. |

| Tracer Dyes (e.g., fluorescein, phenol red) | To visualize mixing patterns and dead zones in bioreactor prototypes. |

| Advanced Cell Culture Media (with defined components) | Essential for precise kinetic modeling, as complex hydrolysates introduce unknown variables. |

The Impact of Gradients on Cell Health, Productivity, and Product Quality Attributes

Within biopharmaceutical manufacturing, bioreactor homogeneity is an idealized condition rarely achieved in practice. The formation of physicochemical gradients—in dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, nutrients, and waste products—is inevitable due to mixing limitations. This technical guide, framed within a broader thesis on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation for bioreactor gradient analysis, elucidates how these gradients directly impact cellular physiology, process productivity, and critical quality attributes (CQAs) of therapeutic proteins. For researchers and process development professionals, understanding and mitigating gradient effects is paramount for robust scale-up and quality-by-design (QbD) implementation.

Gradient Formation and Key Physicochemical Parameters

Gradients arise from the interplay between mass transfer, fluid flow, and cellular consumption/production rates. Key parameters are summarized below.

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Gradients and Their Typical Ranges in Large-Scale Bioreactors

| Parameter | Typical Gradient Range (Scale-Dependent) | Primary Driver | Direct Cellular Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | 10-100% saturation | Oxygen uptake rate (OUR) vs. kLa | Oxidative stress, metabolic shift |

| pH | 0.1 - 0.5 units | Lactic/CO2 production vs. base addition | Enzyme activity, metabolism, growth |

| Nutrient (e.g., Glucose) | 0.5 - 5 g/L | Specific consumption rate vs. mixing | Feast-famine cycles, overflow metabolism |

| Metabolite (e.g., Lactate) | 1 - 10 mM | Production rate vs. dilution/removal | Inhibitory, osmolality shift |

| Carbon Dioxide (pCO2) | 50 - 150 mmHg | Cellular respiration vs. stripping | Altered intracellular pH, glycosylation |

Impact on Cell Health and Signaling

Cells circulating through gradient zones experience dynamic, non-steady-state conditions, triggering stress responses.

Hypoxia/Anoxia Gradients

Cyclic exposure to low DO activates the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF-1α) pathway, altering gene expression.

Experimental Protocol 1: Quantifying HIF-1α Response to DO Gradients

- Setup: Use a dual-vessel system or a compartmentalized bioreactor where cells are periodically shuttled between a normoxic (80% DO) zone and a hypoxic (5% DO) zone, controlling residence time.

- Sampling: Rapidly sample cells from each zone and immediately fix for intracellular analysis.

- Analysis: Perform western blotting for HIF-1α protein stabilization and nuclear localization. Use RT-qPCR for downstream targets (e.g., GLUT1, VEGF, PDK1).

- Correlation: Measure lactate production rate and specific growth rate concurrently. Correlate with HIF-1α activation levels and cycling frequency using CFD-modeled residence times.

Title: HIF-1α Pathway Activation by DO Gradients

pH and Nutrient Gradient Effects

Oscillating glucose concentrations drive "feast-famine" metabolism, leading to sustained lactate production (the Warburg effect) even under ample baseline nutrient supply.

Impact on Productivity and Product Quality Attributes

Gradients directly affect both titer and CQAs, presenting a significant scale-up challenge.

Table 2: Documented Impacts of Gradients on Product CQAs

| Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) | Gradient Type | Observed Effect | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycosylation Pattern | pCO2 / pH | Reduced galactosylation; Increased high-mannose species | Altered Golgi pH & enzyme activity (e.g., β-galactosyltransferase) |

| Charge Variants | pH | Increase in acidic variants | Susceptibility to deamidation at neutral/basic pH |

| Aggregation | Gas (CO2/O2) Interface | Increased soluble aggregates | Surface-induced stress at sparged gas bubbles |

| Peptide Mapping | Nutrient (Glutamine) | Altered C-terminal lysine processing | Variable protease activity under stress |

Experimental Protocol 2: Linking pCO2 Gradients to Glycosylation

- Reactor Configuration: Operate a scaled-down model (e.g., 2L) with controlled pCO2 accumulation (via gassing strategy) to mimic high-pCO2 zones predicted by CFD in a large-scale vessel.

- Sample Strategy: Harvest cells and supernatant from both "high-pCO2" simulated and control conditions throughout the production phase.

- Product Analysis: Purify mAb via Protein A. Perform released N-glycan analysis using HILIC-UPLC/FLR. Quantify relative percentages of G0F, G1F, G2F, and high-mannose (Man5) glycoforms.

- Data Integration: Correlate specific glycoform shifts with both time-averaged and peak pCO2 exposure levels derived from CFD simulations.

Title: pCO2 Gradient Effect on Glycosylation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Gradient Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function in Gradient Research | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent DO / pH Sensors | Real-time, single-cell resolution mapping of gradients in scale-down models. | Pre-loaded nanoparticles (e.g., Ru-Phen complexes for DO). |

| Metabolomic Assay Kits | Quantify rapid changes in central carbon metabolites (glucose, lactate, etc.) from micro-samples. | Coupled enzymatic assays (e.g., YSI Bioprofile) or LC-MS kits. |

| HIF-1α Activity Assay | Quantify nuclear HIF-1α levels as a biomarker for hypoxic stress. | ELISA-based or reporter cell lines (HRE-driven luciferase). |

| N-Glycan Preparation & Labeling Kits | Standardized preparation of glycans for HILIC or CE analysis to assess CQA impact. | Kits for PNGase F release, 2-AB labeling, and cleanup. |

| Live/Dead Viability Assays | Assess spatial or temporal viability loss due to gradient-induced stress. | Fluorescence microscopy with calcein-AM (live) & PI (dead). |

| CFD Software with Population Balance Models | Simulate gradient formation and cell trajectory history. | Ansys Fluent, COMSOL with custom biokinetic subroutines. |

CFD Simulation as a Predictive and Mitigation Tool

CFD transcends point measurement limitations by providing a holistic, time-resolved 3D map of environmental variables. Coupled with kinetic models of cell metabolism, it can predict:

- Gradient Magnitude: Location and severity of DO, pH, and nutrient lows.

- Cycling Frequency: How often cells transition between extreme zones.

- Population Heterogeneity: The distribution of cellular experience histories.

This predictive power allows for the in-silico design of mitigation strategies, such as optimized impeller design, sparger placement, and feeding strategies, before costly pilot-scale experiments.

Gradients in pH, DO, nutrients, and metabolites are not merely operational curiosities but fundamental determinants of process performance and product quality. A systematic, multi-disciplinary approach—combining advanced scale-down experimentation, high-throughput analytics, and predictive CFD simulation—is essential to deconvolute their effects. This integrated strategy is critical for achieving true scale-up success and ensuring the consistent production of biotherapeutics with desired CQAs.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is a branch of fluid mechanics that uses numerical analysis and data structures to analyze and solve problems involving fluid flows. Within the domain of bioprocess engineering, CFD has emerged as an indispensable predictive analysis tool for the design, optimization, and scale-up of bioreactors. This is particularly critical for bioreactor gradient analysis research, where understanding spatial heterogeneity in parameters like dissolved oxygen, nutrients, pH, and shear stress is paramount for ensuring optimal cell growth, viability, and product yield in therapeutic protein and advanced therapy medicinal product (ATMP) development. This whitepaper details the application of CFD as a predictive tool within this specific research thesis context.

Core Principles and Governing Equations

CFD solves the fundamental governing equations of fluid dynamics—the Navier-Stokes equations—discretized over a computational mesh representing the bioreactor geometry. For bioreactor analysis, additional transport equations for species concentration (e.g., nutrients, metabolites, dissolved gasses) and turbulence models (e.g., k-ε, k-ω SST) are coupled. The conservation equations are:

- Conservation of Mass (Continuity):

∂ρ/∂t + ∇·(ρu) = 0 - Conservation of Momentum (Navier-Stokes):

ρ(∂u/∂t + (u·∇)u) = -∇p + ∇·τ + F - Conservation of a Scalar (e.g., Species, Energy):

∂(ρφ)/∂t + ∇·(ρuφ) = ∇·(Γ∇φ) + S_φ

Where ρ is density, u is velocity vector, p is pressure, τ is stress tensor, F represents body forces, φ is the scalar quantity, Γ is diffusivity, and S_φ is the source term (e.g., oxygen uptake rate).

Quantitative Data from Recent CFD Studies in Bioreactor Analysis

The predictive capability of CFD is validated against experimental data. Key quantitative findings from recent literature (2023-2024) are summarized below.

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of CFD Studies for Stirred-Tank Bioreactors

| Study Focus | Bioreactor Scale & Type | Key CFD-Predicted Metric | Predicted Value Range | Experimental Validation Correlation (R²) | Primary Finding for Gradient Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixing Time | 15L, Single-Impeller | Blend Time (θ) for 95% homogeneity | 12 - 48 s (varies with agitation) | 0.92 - 0.97 | Impeller placement is more critical than speed alone for eliminating dead zones. |

| Shear Stress | 5L, Microcarrier-based | Volumetric Average Shear Stress | 0.05 - 0.5 Pa | 0.88 | Identified a 15% volume region near the impeller where stress exceeds 1.0 Pa, critical for sensitive cell types. |

| Dissolved O₂ Gradient | 2000L, Large-Scale MAb Production | Spatial O₂ Concentration Gradient | 20% - 100% Sat. (top to bottom) | 0.85 - 0.90 | Predicts hypoxic zones (<30% sat.) in lower quadrant, informing sparger redesign. |

| pH Gradient | 50L, Perfusion System | Local pH Deviation from Setpoint | +/- 0.3 pH units | 0.80 | Acid/base addition port location was suboptimal, causing local extremes. |

| CO₂ Stripping | 500L, Orbital Shaken | kLa for CO₂ removal | 2 - 8 h⁻¹ | 0.93 | Confirmed headspace flow rate as the dominant factor for CO₂ removal, not shaking speed. |

Detailed CFD Protocol for Bioreactor Gradient Analysis

The following methodology outlines a standard workflow for using CFD to analyze gradients in a stirred-tank bioreactor, aligned with thesis research objectives.

Experimental Protocol: CFD Simulation of Nutrient Gradient in a Mammalian Cell Bioreactor

Objective: To predict the spatial distribution and time evolution of a key nutrient (e.g., Glucose) and a metabolic by-product (e.g., Lactate) under defined operating conditions.

Software Requirements: Commercial (ANSYS Fluent, COMSOL Multiphysics) or Open-Source (OpenFOAM) CFD suite with species transport and multiphase capabilities.

Procedure:

- Geometry Creation & Mesh Generation:

- Create a precise 3D CAD model of the bioreactor vessel, including impeller(s), sparger, baffles, and ports.

- Generate a computational mesh. For impeller rotation, use a Sliding Mesh or Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) approach. Perform a mesh independence study to ensure results are not grid-dependent. A final cell count of 2-5 million is typical for standard vessels.

Physics & Model Setup:

- Solver: Use a pressure-based, transient solver.

- Turbulence Model: Select the Shear Stress Transport (SST) k-ω model for its accuracy in predicting flow separation and shear.

- Multiphase Model: Use the Eulerian-Eulerian model for gas-liquid dispersion if sparging is modeled explicitly, or a simpler algebraic slip mixture model.

- Species Transport: Activate species transport equations. Define glucose and lactate as user-defined scalars.

- Boundary Conditions:

- Impeller: Rotating wall or MRF zone with specified RPM.

- Sparger (if modeled): Mass-flow inlet for gas (air/O₂).

- Liquid Inlets/Outlets (for perfusion): Mass-flow or velocity inlets.

- Walls: No-slip condition for liquid, standard wall functions for turbulence.

Source Term Implementation (Critical for Gradients):

- Incorporate User-Defined Functions (UDFs) to model biological consumption/production.

- Glucose UDF:

S_glucose = - (q_Gluc * X / Y_x/s) * Cell_Density_Field. Whereq_Glucis specific uptake rate,Xis viable cell density,Y_x/sis yield coefficient. - Lactate UDF:

S_lactate = + (q_Lac * X) * Cell_Density_Field. Whereq_Lacis specific production rate. - Cell density can be modeled as uniform or as a spatially variable field from a cell population balance model (PBM) coupling.

Solution & Convergence:

- Initialize the flow field. Use a second-order discretization scheme for accuracy.

- Run the transient simulation for at least 10-15 full impeller revolutions to achieve a quasi-steady state for flow. Then, continue to monitor species distribution.

- Monitor residuals for continuity, momentum, and species equations to fall below 1e-4.

Post-Processing & Analysis:

- Extract contour plots and isosurfaces for glucose and lactate concentration.

- Calculate the coefficient of variation (CoV) for these scalars to quantify gradient severity.

- Plot concentration over time at specific monitor points (e.g., near impeller, near top surface, near bottom corner).

- Perform virtual experiments by changing parameters (RPM, sparger location, feed strategy) and compare gradient outcomes.

Visualizing the Integrated CFD-Bioreactor Analysis Workflow

CFD Workflow for Bioreactor Gradient Analysis

The Scientist's CFD Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key "Research Reagent Solutions" for CFD-Enabled Bioreactor Gradient Analysis

| Item / Solution | Function in the "Experiment" | Technical Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity CAD Model | The digital twin of the bioreactor. Serves as the spatial foundation for all simulations. | Must include all internals. Accuracy is critical for predictive results. File formats: STEP, IGES. |

| Anisotropic Computational Mesh | Discretizes the CAD geometry into cells (control volumes) where equations are solved. | Boundary layer refinement near walls and impeller is essential for shear stress prediction. |

| Turbulence Model (SST k-ω) | Mathematical closure for Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations. Predicts eddy viscosity. | Preferred for its robustness in predicting flow separation under adverse pressure gradients common in bioreactors. |

| User-Defined Function (UDF) | Custom code (C/Python) to implement complex source/sink terms (e.g., cell metabolism, kinetics). | Bridges CFD with biokinetic models. Enables dynamic, cell-density-dependent gradient analysis. |

| Species Transport Model | Solves additional convection-diffusion-reaction equations for nutrients, metabolites, and dissolved gasses. | The core module for quantifying concentration gradients of key process variables. |

| Multiphase Model (Eulerian) | Models the interaction between dispersed gas (bubbles) and continuous liquid (culture medium). | Necessary for predicting gas hold-up, mass transfer (kLa), and gradients in dissolved O₂/CO₂. |

| Validation Dataset (e.g., PIV, Tracer) | Experimental data used to calibrate and validate the CFD model's predictions. | Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) provides velocity field data. Tracer studies provide mixing time data. |

CFD provides an unparalleled, non-invasive window into the complex hydrodynamic and mass transfer environment of bioreactors. As a predictive analysis tool, it moves the field beyond empirical correlations and enables a first-principles approach to understanding and controlling gradients. Within the thesis context of bioreactor gradient analysis research, CFD is not merely a simulation tool but a foundational technology for de-risking bioprocess scale-up, optimizing cell culture conditions, and ultimately ensuring the robust and reproducible manufacturing of next-generation therapeutics. The integration of advanced UDFs for cell metabolism and coupling with population balance models represents the frontier of this field, promising ever-more predictive digital twins of bioprocesses.

This technical guide, framed within a broader thesis on CFD simulation for bioreactor gradient analysis research, details the fundamental physics governing the operation of bioreactors. Accurate modeling of fluid flow, turbulence, and species transport is critical for predicting nutrient distribution, shear stress on cells, and product yield. This document provides an in-depth analysis of the governing equations, quantitative data from current literature, experimental protocols for validation, and essential tools for researchers in biopharmaceutical development.

Governing Physics and Mathematical Models

The core physics of bioreactor operation is described by the conservation laws of mass, momentum, and species. These are typically solved using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) within the context of the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) framework for turbulent flows.

Key Equations:

Continuity (Mass Conservation): [ \frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{u}) = 0 ] For incompressible flows, this simplifies to (\nabla \cdot \vec{u} = 0).

Momentum Conservation (RANS): [ \frac{\partial (\rho \vec{u})}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{u} \vec{u}) = -\nabla p + \nabla \cdot (\mu{eff}(\nabla \vec{u} + (\nabla \vec{u})^{T})) + \rho \vec{g} + \vec{F} ] where (\mu{eff} = \mu + \mut), and (\mut) is the turbulent viscosity modeled by turbulence closures (e.g., k-ε, k-ω).

Species Transport (Nutrients, Oxygen, Metabolites): [ \frac{\partial (\rho Yi)}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{u} Yi) = \nabla \cdot (\rho D{eff} \nabla Yi) + Ri ] where (Yi) is the mass fraction, (D{eff}) is the effective diffusivity (molecular + turbulent), and (Ri) is the volumetric consumption/production rate from cell metabolism.

Turbulence Modeling: The standard k-ε model remains widely used for its robustness, though more advanced models like Scale-Resolving Simulations (SAS, DES) are gaining traction for capturing transient gradients.

Table 1: Typical Operating Parameters and Model Constants for Stirred-Tank Bioreactors

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range (Mammalian Cell Culture) | Common k-ε Model Constants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impeller Reynolds Number | (Re = \frac{\rho N D^2}{\mu}) | (10^4 - 10^5) (Turbulent) | Cμ = 0.09 |

| Tip Speed | (V_{tip} = \pi N D) | 1.0 - 2.5 m/s | Cε1 = 1.44 |

| Volumetric Oxygen Transfer Coefficient | (k_La) | 5 - 50 h⁻¹ | Cε2 = 1.92 |

| Oxygen Uptake Rate (OUR) | (OUR) | 2 - 15 mmol/L/h | σ_k = 1.0 |

| Power Input per Unit Volume | (P/V) | 50 - 500 W/m³ | σ_ε = 1.3 |

Table 2: Impact of Turbulence Model Choice on Gradient Prediction Accuracy (Comparative Study)

| Model Type | Computational Cost (Relative to RANS k-ε) | Prediction of Shear Stress | Prediction of Local Nutrient Gradients | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RANS (Standard k-ε) | 1x | Moderate | Low-Moderate | Steady-state scaling, initial design |

| RANS (SST k-ω) | ~1.2x | Good | Moderate | Flows with separation, better shear prediction |

| LES (Large Eddy Simulation) | 50-100x | Excellent | Excellent | Detailed transient gradient analysis, validation studies |

| Hybrid RANS-LES (DES) | 10-30x | Good-Excellent | Good-Excellent | Analysis of large-scale transient instabilities |

Experimental Protocols for CFD Model Validation

Protocol 1: Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) for Flow Field Validation

- Objective: Obtain time-resolved velocity field data for comparison with CFD simulations.

- Setup: Use a bioreactor constructed of transparent material (e.g., acrylic) with refractive index-matched fluid. Seed the fluid with neutrally buoyant tracer particles (e.g., hollow glass spheres, 10-50 μm).

- Procedure: Illuminate a thin laser sheet in the plane of interest. Capture successive image pairs with a synchronized high-resolution CCD camera.

- Analysis: Use cross-correlation algorithms (e.g., in DaVis, OpenPIV) to calculate the displacement vector field between image pairs. Derive velocity and vorticity fields. Compare statistically (mean velocity, turbulence kinetic energy) with CFD results.

Protocol 2: Planar Laser-Induced Fluorescence (PLIF) for Species Concentration Validation

- Objective: Measure two-dimensional concentration fields of a tracer (e.g., acid, base, fluorescent dye) to validate species transport models.

- Setup: Use a fluorescent tracer (e.g., Rhodamine B) with concentration proportional to fluorescence intensity. Utilize the same transparent vessel as in PIV.

- Procedure: Pulse a laser sheet through the vessel. Use a camera fitted with an appropriate optical filter to capture the fluorescence emission. Perform a calibration to relate pixel intensity to concentration.

- Analysis: Record concentration decay or mixing times after a pulse injection. Compare the transient 2D concentration fields and mixing time scales with those predicted by the coupled CFD-species transport simulation.

Visualizing the CFD Workflow for Bioreactor Analysis

Diagram Title: CFD Workflow for Bioreactor Gradient Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Experimental Model Validation

| Item/Reagent | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Refractive Index Matched Fluid (e.g., NaI or Glycerol solutions) | Enables optical access for PIV/PLIF by minimizing laser distortion. | Must match acrylic/glass refractive index; should be non-toxic if using live cells. |

| Neutrally Buoyant Seeding Particles (e.g., Hollow Glass Spheres, PSL) | Tracers for PIV to visualize fluid motion. | Size (10-50 μm) and density must match fluid to follow flow accurately. |

| Fluorescent Tracer Dye (e.g., Rhodamine B, Fluorescein) | Passive scalar for PLIF to visualize mixing and concentration fields. | Must be inert, photostable, and have a high quantum yield. |

| Non-Invasive pH & pO2 Probes (e.g., Optical Sensor Spots) | Provides point validation data for local species concentrations. | Must be sterilizable and miniaturized to avoid flow disturbance. |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics Software (e.g., ANSYS Fluent, OpenFOAM, COMSOL) | Solves the core physics equations numerically. | Choice depends on required models (e.g., multiphase, UDF capability), budget, and user expertise. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables high-fidelity (LES, multiphase) simulations in reasonable time. | Core count, RAM, and fast interconnect are critical for scaling. |

A Step-by-Step Guide to Setting Up a CFD Simulation for Bioreactor Analysis

This guide details the foundational pre-processing stage for Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations, specifically within a research thesis analyzing concentration and shear stress gradients in bioreactors for mammalian cell culture and advanced therapeutic medicinal product (ATMP) development. Accurate pre-processing is critical for predicting nutrient distribution, waste accumulation, and hydrodynamic stress, which directly impact cell viability, growth, and product quality.

Geometry Creation for Bioreactors

Core Principles

Geometry must represent the physical bioreactor (e.g., stirred-tank, wave, fixed-bed) with all relevant internals. Simplifications are made judiciously to reduce computational cost while preserving flow physics.

Key Components & Dimensional Data

Table 1: Standard Geometrical Parameters for a Bench-Scale Stirred-Tank Bioreactor

| Component | Typical Dimension (Relative to Tank Diameter, T) | Function in Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Tank Diameter (T) | 0.1 - 0.3 m | Sets the global scale of the system. |

| Liquid Height (H) | H = 1.0T - 1.5T | Defines the working volume. |

| Impeller Diameter (D) | D = 0.3T - 0.5T | Primary driver of fluid motion and mixing. |

| Impeller Bottom Clearance | C = 0.25T - 0.33T | Affects bottom flow and dead zone formation. |

| Baffle Width | 0.08T - 0.1T | Prevents solid-body rotation and promotes vertical mixing. |

Detailed Protocol: Geometry Cleanup

- Import/Construction: Import a detailed CAD model or construct the geometry using the simulation software's native tools (e.g., ANSYS DesignModeler, Siemens NX).

- Defeaturing: Remove non-essential features (e.g., small fillets, threads, manufacturer logos) that do not significantly affect global flow patterns but create problematic mesh elements. A standard rule is to remove details smaller than 1% of T.

- Watertight Volume Creation: Ensure all fluid regions (e.g., liquid, sparged air) form a single, contiguous, leak-proof volume. Perform a "stitching" or "healing" operation to merge adjacent surfaces.

- Named Selections: Assign clear names to boundary surfaces:

Vessel_Wall,Impeller_Surface,Baffle_Surface,Sparger_Inlet,Headspace_Outlet,Symmetry_Plane(if used).

Meshing Strategies

Mesh Types and Applications

Table 2: Comparison of Meshing Approaches for Bioreactor CFD

| Mesh Type | Best For | Typical Cell Count for 3L Reactor | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrahedral (Unstructured) | Complex geometries (e.g., impellers, probes). | 2 - 5 million | Automated generation, handles complexity. | Higher cell count needed for equivalent accuracy; skewed cells near walls. |

| Hexahedral (Structured) | Simple or decomposable geometries (e.g., baffled tank without impeller). | 0.5 - 2 million | Higher accuracy per cell, lower numerical diffusion. | Difficult to generate for complex shapes. |

| Polyhedral | Complex turbulent flows with swirling. | 1 - 3 million | Lower cell count for same accuracy, better convergence. | Higher memory usage per cell. |

| Cut-Cell (e.g., ANSYS FFE) | Complex moving geometries (e.g., rotating impeller). | 1 - 4 million | High accuracy with Cartesian background mesh. | Requires careful sizing near walls. |

Experimental Protocol: Mesh Independence Study

A core requirement for credible thesis results.

- Initial Mesh: Generate a baseline mesh with software-recommended sizing.

- Simulation Run: Solve for key global parameters (e.g., impeller power number, blend time) until convergence.

- Refinement: Create 3-4 progressively finer meshes by globally reducing the base element size by ~25% each step. Use local refinement in critical regions (impeller discharge, near walls, sparger region).

- Comparison: Plot the key output parameters against the inverse of total cell count (1/N).

- Selection: Identify the point where the parameter change between successive meshes is less than a predetermined threshold (e.g., <2%). The mesh before this point is the optimal choice.

Choosing Solver Settings

Physics-Based Model Selection

Table 3: Solver Model Selection for Bioreactor Gradient Analysis

| Physical Phenomenon | Recommended Model | Thesis Application Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Turbulence | k-ω SST (Shear Stress Transport) | Most accurate for predicting wall shear stress—critical for shear-sensitive cells—and handling separated flows. |

| Multiphase (Sparging) | Euler-Euler (for gas holdup >10%) or Volume of Fluid (VOF, for interface tracking). | Models oxygen mass transfer from bubbles to liquid, a key gradient driver. |

| Species Transport | Species Transport with Multi-Component Mixtures. | Simulates gradients of nutrients (glucose), metabolites (lactate), and dissolved gases (O₂, CO₂). |

| Rotation | Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) or Sliding Mesh. | MRF for steady-state mixing; Sliding Mesh for transient analysis of impeller-passing effects on gradients. |

Boundary & Initial Conditions Protocol

- Inlet (Sparger): Set as mass-flow inlet or velocity inlet. Specify gas volume fraction (1.0) and gas velocity based on the Superficial Gas Velocity (e.g., 0.001 - 0.01 m/s).

- Impeller Region (MRF): Define a fluid zone around the impeller. Assign rotational speed (e.g., 50-150 RPM). Use the Moving Reference Frame model.

- Walls: Apply no-slip condition. Use standard wall functions or enhanced wall treatment depending on near-wall mesh resolution (y+ target: ~1 for shear stress, 30-300 for mixing studies).

- Outlet (Headspace): Set as pressure outlet with zero gauge pressure. Define backflow conditions for volume fraction (e.g., 1.0 for air).

- Initialization: Patch initial values for species concentrations (e.g., dissolved oxygen at 10% saturation) to simulate start-of-culture conditions.

Solution Methods and Convergence

- Pressure-Velocity Coupling: Use the Coupled scheme for robustness and faster convergence.

- Spatial Discretization: Use Second-Order Upwind for momentum, turbulence, and species to minimize false diffusion of gradients.

- Convergence Criteria: Set monitors for residuals (target: 1e-5 for energy/species, 1e-4 for others) AND key physical quantities (e.g., torque on impeller, average velocity in a zone). Ensure these are stable over hundreds of iterations/steps.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Bioreactor Gradient Validation Experiments

| Item | Function in Validating CFD Models |

|---|---|

| Non-Invasive pH & DO Probes (e.g., Hamilton VisiFerm, PreSens) | Provide real-time, local concentration data at specific vessel locations for direct comparison with CFD species transport results. |

| Planar Laser-Induced Fluorescence (PLIF) Tracers (e.g., Rhodamine B) | Enables 2D visualization of mixing and concentration gradient dissipation in a optically accessible model bioreactor. |

| Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) Seeding Particles (e.g., hollow glass spheres) | Used to capture 2D/3D velocity vector fields for validating CFD-predicted flow patterns and turbulence kinetic energy. |

| Shear-Sensitive Microcapsules or Dye Release Beads | Qualitative or quantitative indicators of local shear stress magnitude, correlating to CFD-predicted wall shear stress. |

| Computational Resources (High-Performance Computing Cluster with ≥ 128 GB RAM, 32+ cores) | Essential for solving the high-fidelity, transient, multiphase CFD models required for gradient analysis within a practical timeframe. |

Visualizations

Title: CFD Pre-Processing Workflow for Bioreactors

Title: Physics Model Selection for Bioreactor Gradients

This guide addresses a critical component of a broader doctoral thesis focused on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation for bioreactor gradient analysis. Accurate prediction of nutrient, metabolite, and dissolved oxygen gradients—which directly impact cell viability, productivity, and product quality—is wholly dependent on the implementation of physically realistic boundary conditions (BCs). This document provides an in-depth technical protocol for defining the three most influential BC sets in stirred-tank bioreactors: impeller-induced flow, gas sparging, and media perfusion.

Impeller Speed: Defining the Rotating Domain

The impeller is the primary driver of fluid motion, mixing, and shear. In CFD, it is typically modeled using the Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) or Sliding Mesh approach.

2.1 Quantitative Parameters & Data Table

| Parameter | Typical Range (Mammalian Cell Culture) | CFD Boundary Condition Type | Key Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agitation Rate (N) | 50 - 150 rpm | Rotational velocity in MRF zone | Power input, mixing time, shear stress |

| Tip Speed (Vtip = π*D*N) | 0.5 - 1.5 m/s | Derived parameter | Maximum local shear, cell damage potential |

| Reynolds Number (Re = ρND²/μ) | >10⁴ (Turbulent) | Determines turbulence model selection | Flow regime (laminar/transitional/turbulent) |

| Power Number (Np) | ~0.5 - 5 (geometry-dependent) | Used to calculate power input | Absolute power dissipation (P = NpρN³D⁵) |

2.2 Experimental Protocol for Validation: Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV)

- Objective: Obtain experimental velocity field data to validate CFD-predicted flow patterns from the impeller BC.

- Materials: Seeded tracer particles, laser sheet generator, high-speed camera, bioreactor with transparent section (e.g., flat-bottom glass vessel).

- Method:

- Fill bioreactor with a fluid matching culture media density/viscosity.

- Seed fluid with neutrally buoyant, reflective tracer particles (~10-100 µm).

- Operate impeller at target speed (N) in a dark environment.

- Illuminate a vertical or horizontal plane with a thin laser sheet.

- Capture sequential image pairs with a synchronized high-speed camera.

- Use cross-correlation algorithms (e.g., in MATLAB or DaVis) to calculate the 2D vector field from particle displacement.

- Compare time-averaged PIV velocity magnitude and direction to CFD results at identical planes.

Gas Sparging: Modeling the Discrete Phase

Gas sparging for oxygen transfer and CO₂ stripping introduces a complex, two-phase flow. The Eulerian-Eulerian or Eulerian-Lagrangian frameworks are commonly used.

3.1 Quantitative Parameters & Data Table

| Parameter | Typical Range | CFD Boundary Condition Type | Key Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial Gas Velocity (Vs) | 0.0005 - 0.005 m/s (low-shear) | Inlet velocity or mass flow rate at sparger holes | Gas holdup, residence time, mass transfer (kLa) |

| Bubble Size (db) | 2 - 5 mm (coarse), 0.5 - 2 mm (micro) | Discrete Phase Model (DPM) initial diameter or population balance input | Interfacial area, coalescence/breakup behavior |

| Oxygen Mass Transfer Coefficient (kLa) | 1 - 20 h⁻¹ | Validation metric from simulation results | System oxygenation capacity |

| Sparger Type & Hole Pattern | Ring, open pipe, microporous | Physical geometry and inlet boundary placement | Initial bubble distribution, plume dynamics |

3.2 Experimental Protocol for Validation: Dynamic Gas Disengagement (DGD)

- Objective: Measure gas holdup and characterize bubble size distribution to inform sparging BCs.

- Materials: Conductivity or pressure probes, high-speed video camera, image analysis software.

- Method:

- Sparge gas at the target Vs until steady state is reached.

- Abruptly stop the gas flow.

- Record the rate of liquid level decline (via probe or video) as bubbles disengage. The disengagement curve can be deconvoluted to estimate fractions of small vs. large bubbles.

- Simultaneously, use high-speed video of the rising bubble plume and image analysis (e.g., ImageJ) to obtain a statistical distribution of bubble diameters.

- Use the measured average diameter and holdup to set the initial bubble conditions and validate the simulated two-phase flow field.

Inlet/Outlet Flows: Perfusion & Feed Strategies

Perfusion systems maintain cells at high density by continuously adding fresh media and removing spent media, creating concentration gradients.

4.1 Quantitative Parameters & Data Table

| Parameter | Calculation / Typical Value | CFD Boundary Condition Type | Key Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfusion Rate (D) | 1 - 5 reactor volumes per day | Inlet: velocity or mass flow rate. Outlet: pressure-outflow or specified flux. | Nutrient/metabolite gradient steepness, cell-specific perfusion rate |

| Inlet Velocity / Location | Vin = (D*Vreactor)/(Ainlet*86400) | Velocity-inlet BC at feed port | Local mixing, potential for shear or cell retention at filter |

| Outlet Configuration | Closed (batch), open (perfusion), with cell retention device | Pressure-outlet BC, often with zero diffusive flux for species | System pressure, defines residence time distribution |

4.2 Experimental Protocol for Validation: Tracer Pulse Response

- Objective: Characterize the residence time distribution (RTD) to validate perfusion flow BCs and mixing.

- Materials: Tracer (e.g., NaCl, dye, pH step-change), conductivity/pH/UV probe at outlet, data logger.

- Method:

- Establish steady-state perfusion flow at the target rate (D).

- Inject a short, concentrated pulse of tracer at the inlet port.

- Continuously measure tracer concentration at the outlet stream over time.

- Plot the normalized concentration (C-curve) vs. time. The mean of this distribution equals the theoretical residence time (τ = Vreactor/Q) if BCs are accurate.

- Compare the experimentally measured RTD curve to the CFD-predicted RTD from a simulated tracer study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Material Solutions

| Item | Function in BC Definition & Validation |

|---|---|

| Polyamide Seeding Particles (10-50 µm) | Neutrally buoyant tracers for Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) to validate impeller-induced flow. |

| Silicone Oil (with matched refractive index) | Fluid for PIV that matches bioreactor fluid's refractive index to minimize laser distortion. |

| High-Speed CMOS Camera (>500 fps) | Captures rapid flow dynamics for PIV and bubble image analysis. |

| Planar Laser Sheet Optics | Creates a thin illuminated plane for 2D flow field measurement in PIV. |

| Conductivity/Tracer Probes | Measures concentration changes for Residence Time Distribution (RTD) and Gas Holdup studies. |

| Image Analysis Software (e.g., ImageJ, DaVis) | Processes PIV image pairs and analyzes bubble size distributions from high-speed video. |

| CFD Software (ANSYS Fluent, COMSOL, OpenFOAM) | Platform for implementing boundary conditions and solving the governing fluid dynamics equations. |

Visualizing the Integrated Workflow and Relationships

Diagram 1: BC Definition & Validation Workflow (94 chars)

Diagram 2: CFD BC Validation Feedback Loop (94 chars)

Material Properties and Multiphase Models for Gas-Liquid Interactions

Within the context of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation for bioreactor gradient analysis research, the accurate modeling of gas-liquid interactions is paramount. These interactions govern oxygen mass transfer, carbon dioxide stripping, and nutrient distribution, which are critical for cell culture viability and productivity in pharmaceutical bioprocessing. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide on the material properties and multiphase modeling approaches essential for simulating these complex systems.

Fundamental Material Properties

The accurate definition of material properties is the foundation of any credible multiphase CFD simulation. For bioreactor applications, the primary phases are the liquid culture medium (often water-based) and the gas phase (typically air or an oxygen-enriched mixture).

Key Properties for Gas and Liquid Phases

The following properties must be characterized as functions of temperature, pressure, and composition.

Table 1: Critical Material Properties for Bioreactor CFD Simulations

| Property | Liquid Phase (Culture Medium) | Gas Phase (Air/O₂) | Dependency & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (ρ) | ~998 - 1020 kg/m³ | ~1.185 kg/m³ (at 25°C) | Medium: Composition, cell density. Gas: Ideal gas law recommended. |

| Viscosity (μ) | ~0.89 - 1.5 mPa·s | ~1.85e-5 Pa·s | Medium: Strong function of extracellular matrix, cell concentration. |

| Surface Tension (σ) | 0.06 - 0.072 N/m | N/A | Critical for bubble size. Reduced by surfactants/proteins. |

| Diffusivity of O₂ (D) | ~2.1e-9 m²/s | ~1.76e-5 m²/s | Liquid: Strong function of medium viscosity and solutes. |

| Henry's Law Constant (H) | ~7.8e4 Pa/(mol/m³) for O₂ | N/A | Defines O₂ solubility. Temperature dependent. |

| Heat Capacity (Cp) | ~4180 J/(kg·K) | ~1005 J/(kg·K) | Required for non-isothermal simulations. |

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Essential materials for experimental validation of simulated properties.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Property Characterization

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Dynamic Interfacial Tensiometer | Measures gas-liquid surface tension under process conditions (e.g., with proteins present). |

| Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) Tracers | Seeding particles (e.g., fluorescent polymer microspheres) for experimental flow field mapping. |

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) Probes (Optochemical) | Validates simulated oxygen concentration fields. Must be sterilizable for in-situ use. |

| pH & Conductivity Sensors | Tracks ionic composition changes affecting fluid properties and bubble coalescence. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) Solution | Used as a standard or model fluid with controlled, tunable viscosity and surface tension. |

| Anti-foaming Agents (e.g., Simethicone) | Modifies interfacial properties for studying foam formation and its impact on mass transfer. |

Multiphase Modeling Frameworks

Selecting an appropriate multiphase model is dictated by the morphology of the gas-liquid dispersion.

Model Selection Protocol

Experimental/Simulation Workflow for Model Identification:

- Characterize Regime: Use high-speed imaging to determine bubble size distribution (BSD) and regime (e.g., homogeneous bubbly, churn-turbulent).

- Calculate Key Dimensionless Numbers:

- Gas Volume Fraction (α):

α = V_gas / (V_gas + V_liquid) - Euler Number (Eu):

Eu = Δp / (ρ_l * u²)for pressure forces. - Stokes Number (St):

St = (ρ_p * d_p² * u) / (18 * μ_l * L)for particle/bubble tracing.

- Gas Volume Fraction (α):

- Model Selection:

- If α < 10% and BSD is narrow → Eulerian-Lagrangian (Discrete Phase Model).

- If α > 10% or BSD is broad → Eulerian-Eulerian (Volume of Fluid or Mixture Model).

- Closure & Validation: Select interfacial force closures (drag, lift, virtual mass). Validate simulated α and BSD against experimental data (e.g., from electrical tomography).

Workflow for Multiphase Model Selection

Interfacial Momentum & Mass Transfer Closure

Interfacial Force Models

The momentum exchange between phases is governed by interfacial forces.

Table 3: Common Interfacial Force Closure Models

| Force | Model Equation | Parameters Requiring Experimental Input |

|---|---|---|

| Drag | F_D = (3/4) (α_g ρ_l C_D / d_b) |u_g - u_l| (u_g - u_l) |

Drag Coefficient (C_D, e.g., Schiller-Naumann), Bubble Diameter (d_b). |

| Lift | F_L = α_g ρ_l C_L (u_g - u_l) × (∇ × u_l) |

Lift Coefficient (C_L). Positive for small bubbles, negative for large. |

| Virtual Mass | F_VM = α_g ρ_l C_VM ( (Du_g/Dt) - (Du_l/Dt) ) |

Virtual Mass Coefficient (C_VM, often = 0.5). |

| Turbulent Dispersion | F_TD = -C_TD ρ_l k_l ∇α_g |

Turbulent Dispersion Coefficient (C_TD). |

Mass Transfer (Oxygen Uptake) Protocol

Detailed Methodology for Determining k_L a:

- Objective: Experimentally determine the volumetric mass transfer coefficient (

k_L a) for validation of species transport models. - Equipment: Bioreactor, sterilizable DO probe, nitrogen source, data acquisition system.

- Procedure:

- Deoxygenate the medium by sparging

N₂until DO ~0%. - Switch sparging gas to air or defined

O₂mixture. - Record the DO concentration as a function of time until saturation (

C*).

- Deoxygenate the medium by sparging

- Analysis: Fit the dynamic data to the solution of:

dC/dt = k_L a (C* - C). The slope ofln[(C* - C)/(C* - C₀)]vs.tgivesk_L a.

Oxygen Mass Transfer Pathway in Bioreactor

Integrated CFD Workflow for Gradient Analysis

A complete simulation workflow for predicting gradients in pH, nutrients, and dissolved gases.

Integrated CFD Simulation & Validation Workflow

The fidelity of CFD-based gradient analysis in bioreactors is intrinsically linked to the accurate representation of material properties and the selection of physically sound multiphase models. By employing systematic experimental protocols for property determination and model validation—particularly for interfacial momentum and mass transfer—researchers can develop robust simulations. These simulations become predictive tools for optimizing bioreactor design and operation, ultimately enhancing control over the microenvironment in pharmaceutical cell culture processes.

Setting Up Species Transport Models to Simulate Nutrient and Metabolite Distribution

Within the broader thesis on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation for bioreactor gradient analysis, the accurate modeling of species transport is paramount. Bioreactor performance, particularly for sensitive mammalian cell cultures or microbial fermentations for therapeutic products, is critically dependent on the spatiotemporal distribution of nutrients (e.g., glucose, glutamine, dissolved oxygen) and metabolites (e.g., lactate, ammonia, CO₂). Heterogeneous distributions—gradients—can arise from imperfect mixing, high cell density, or diffusion limitations, leading to zones of suboptimal or toxic conditions that impact cell viability, productivity, and product quality. This guide details the technical setup of species transport models to simulate these distributions, enabling virtual bioreactor analysis and optimization.

Core Mathematical Framework and Governing Equations

Species transport in a bioreactor is governed by the convection-diffusion-reaction equation. For a species i with local mass concentration Cᵢ [kg/m³], the conservation equation is:

∂(ρCᵢ)/∂t + ∇ ⋅ (ρuCᵢ) = ∇ ⋅ (ρDᵢ,eff ∇Cᵢ) + Rᵢ

Where:

- ρ: Fluid density [kg/m³]

- u: Velocity vector [m/s]

- Dᵢ,eff: Effective diffusivity of species i [m²/s]

- Rᵢ: Volumetric reaction source/sink term [kg/(m³·s)]

The reaction term Rᵢ couples hydrodynamics with cell metabolism. For nutrients, it is typically a sink (negative); for metabolites, a source (positive). Accurate formulation of Rᵢ is often the most complex aspect, requiring kinetic models like Monod, Haldane, or structured metabolic models.

Table 1: Typical Governing Equation Parameters for Common Bioreactor Species

| Species | Typical Initial Conc. (Mammalian Cell Culture) | Effective Diffusivity in Aqueous Media (approx., m²/s) | Common Kinetic Model for Uptake/Production | Key Reference Values (from recent literature) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 4-6 g/L | 6.0 × 10⁻¹⁰ | Monod (μmax ~0.05 h⁻¹, Ks ~0.2 mM) | Critical conc. for limitation: <0.5 mM |

| Dissolved Oxygen (DO) | 40-100% air sat. | 2.1 × 10⁻⁹ | Dual-substrate Monod | K_s ~0.01-0.05 mM; critical: <10% sat. |

| Glutamine | 2-4 mM | 7.0 × 10⁻¹⁰ | Monod with decay term | Degradation rate: ~0.002 h⁻¹ at 37°C |

| Lactate | 0-5 g/L (accumulates) | 1.3 × 10⁻⁹ | Luedeking-Piret (growth-associated) | Yield coefficient (Y_{Lac/Glc}): 1-2 mol/mol |

| Ammonia (NH₃/NH₄⁺) | <2 mM (toxic threshold) | 1.8 × 10⁻⁹ | Often simplified constant yield | Toxicity threshold: ~2-5 mM |

| Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) | Equilibrated with gas | 1.7 × 10⁻⁹ | Henry's Law equilibrium & production yield | pCO₂ > 150 mmHg can inhibit growth |

Detailed Methodology: Setting Up a CFD Simulation

Experimental Protocol for Model Calibration and Validation:

Title: In Silico-In Vitro Coupled Protocol for Transport Model Validation

1. Pre-Simulation: Bioreactor Characterization & Meshing

- Objective: Define computational domain and boundary conditions.

- Steps: a. Obtain exact bioreactor geometry (vessel, impeller, sparger, baffles). b. Generate a high-quality computational mesh. For stirred tanks, use a sliding mesh or multiple reference frame (MRF) approach for impeller rotation. Ensure mesh refinement near spargers, impellers, and walls. c. Set boundary conditions: Inlet (gas sparger: gas flow rate, composition; feed inlet: flow rate, composition), Outlet (pressure-outlet), Walls (no-slip for fluid, zero-flux or wall functions for species). d. Define fluid properties (culture media density, viscosity).

2. Phase 1: Hydrodynamic Flow Field Simulation

- Objective: Solve for the steady-state velocity (u) and turbulence fields.

- Steps: a. Select a turbulence model (e.g., k-ε SST is common for baffled stirred tanks). b. Run simulation until residuals converge (typically < 10⁻⁵) and global parameters (power number, P/V) match empirical correlations. c. Validate flow field against Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) data if available.

3. Phase 2: Coupled Species Transport Simulation

- Objective: Solve transient species distribution.

- Steps:

a. Activate Species Transport Model: Enable solving for additional scalar equations.

b. Define Species Properties: Input molecular weights, diffusivities (Dᵢ), and initial concentrations (Cᵢ,₀) for all species (Table 1).

c. Implement Reaction Source Terms (Rᵢ): This is the critical step. Use User-Defined Functions (UDFs) to code kinetic models.

Example UDF for Monod-based glucose consumption:

R_glucose = - (µ_max * C_glucose / (K_s + C_glucose)) * (C_X / Y_xs)where C_X is the local cell density (may also be modeled as a passive scalar or with population balance models). d. Set Multiphase Interactions (if sparging): For dissolved gases (O₂, CO₂), define mass transfer from the gas to liquid phase using a Two-Fluid Model (Eulerian-Eulerian) or Discrete Phase Model (DPM). The mass transfer coefficient (kLa) can be a user input or estimated from correlations. e. Run Transient Simulation: Initialize the domain and run with a suitable time step (e.g., 0.1s). Monitor key volume-averaged concentrations and spatial gradients until a pseudo-steady state or the desired batch time is reached.

4. Post-Processing & Validation

- Objective: Extract quantitative gradient data and validate against experiment.

- Steps:

a. Create iso-surfaces, contour plots, and line probes to visualize concentration gradients (e.g., from impeller to reactor top).

b. Quantify gradient severity: e.g.,

(C_max - C_min) / C_avg. c. Validate by comparing simulated concentration time-profiles at specific locations (e.g., near a pH or DO probe) against data from: * Offline sampling and HPLC/analyzer measurements. * In-line or at-line process analytical technology (PAT) sensors.

Diagram Title: CFD Species Transport Simulation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for Coupled CFD-Experimental Studies

| Item | Function/Application in Gradient Analysis |

|---|---|

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software | ANSYS Fluent, COMSOL Multiphysics, or OpenFOAM. Solves governing equations for flow and species transport. Essential for the in silico model. |

| High-Fidelity Bioreactor Vessel (Lab-Scale) | A well-characterized, instrumented benchtop bioreactor (e.g., 2-5L) with standardized geometry. Serves as the physical validation system. |

| Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) System | Laser-based optical method to measure instantaneous velocity fields in the bioreactor. Critical for validating the simulated hydrodynamic flow field (Phase 1). |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) Probes | In-line sensors for pH, Dissolved Oxygen (DO), and Dissolved CO₂. Provide real-time, spatially specific (at probe location) data for model validation. |

| Autosampler with Bioanalyzer | Automated sampling coupled to systems like Cedex Bio HT or Nova Bioprofile for rapid, frequent measurement of glucose, lactate, ammonium, and other metabolites from multiple time points. |

| Tracer Dyes & Fluorometers | Non-reactive dyes (e.g., fluorescein) used in mixing time studies. Injected tracers can validate scalar mixing and dispersion predictions of the model. |

| Metabolic Quenching Solution | Rapid-quench solutions (e.g., cold methanol/water) for metabolomics sampling. Allows "snapshot" of intracellular metabolism, which can be linked to local extracellular gradients predicted by the model. |

| User-Defined Function (UDF) Compiler | Typically part of the CFD software package. Allows integration of complex, user-coded kinetic models for nutrient consumption and metabolite production into the simulation. |

Advanced Considerations: Modeling Cell Metabolism and Population Effects

For predictive accuracy, the simple constant-yield or Monod models for Rᵢ may be insufficient. Advanced approaches include:

- Coupling with Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA): Using genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to predict uptake/secretion rates as functions of local environment, feeding back into the CFD.

- Discrete Phase Modeling (DPM) for Cells: Treating cells as a discrete particle phase with their own transport and metabolism, suitable for larger aggregates or microcarriers.

- Population Balance Models (PBM): Coupled with CFD (CFD-PBM) to simulate how gradients influence cell cycle distribution, viability, and productivity across the reactor volume.

Diagram Title: Coupling CFD with Metabolic Models

The establishment of rigorous species transport models within a CFD framework is a cornerstone of modern bioreactor gradient analysis research. By meticulously following the protocols for model setup, calibration, and validation—and leveraging the toolkit of computational and experimental resources—researchers can move beyond point measurements to obtain a holistic, three-dimensional understanding of the bioreactor environment. This capability is transformative for scaling up processes, designing next-generation bioreactors with minimized gradients, and ultimately ensuring the consistent production of high-quality biologics and cell therapies.

Within the broader thesis on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation for bioreactor gradient analysis, the post-processing of scalar and velocity fields is critical. Effective visualization and quantification of gradient maps and mixing times directly inform the design and scale-up of bioreactors for biopharmaceutical manufacturing, ensuring optimal cell culture conditions and consistent product quality.

Quantifying Gradient Maps

Gradient maps, derived from CFD solutions for species concentration (e.g., nutrients, metabolites, pH), reveal the spatial heterogeneity within a bioreactor. Key quantification metrics are summarized below.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Quantifying Gradient Maps

| Metric | Formula / Description | Relevance to Bioreactor Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient Magnitude | |∇C| = √[(∂C/∂x)² + (∂C/∂y)² + (∂C/∂z)²] |

Identifies regions of sharp concentration changes that may stress cells. |

| Coefficient of Variation (CoV) | (σ_C / μ_C) * 100% |

Measures global heterogeneity; target often <10-20% for homogeneity. |

| Volume Fraction Below Threshold | V(C < C_crit) / V_total |

Quantifies poorly mixed zones where nutrient limitation may occur. |

| Local Shielding Factor | Ratio of local gradient to average gradient. | Highlights sheltered zones potentially leading to metabolic dormancy. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating CFD Mixing Time Predictions

This protocol details the decolorization method for experimental mixing time (θ_mix) validation, a standard for bioreactor characterization.

Objective: To determine the mixing time in a bioreactor and validate corresponding CFD transient simulations. Materials: See The Scientist's Toolkit below. Procedure:

- Fill the bioreactor with the model fluid (e.g., water) to the working volume. Begin agitation and sparging at the target conditions (RPM, gassing rate).

- Introduce a pulse tracer (e.g., 1M NaOH) at a defined port. Simultaneously, inject a stoichiometric amount of phenolphthalein indicator pre-mixed into the vessel.

- Monitor pH at multiple strategic locations using in-line probes. The tracer neutralizes the indicator, causing decolorization.

- Record the time from tracer addition until the pH at all monitored locations reaches and remains within a specified tolerance (e.g., ±5%) of the final equilibrium value. This is the experimental θ_mix.

- Replicate the experiment (n≥3) for statistical significance.

- In the CFD model, simulate an identical tracer pulse and monitor concentration at virtual probe locations matching the experiment. The simulated θ_mix is determined using the same criterion.

Visualizing Analysis Workflows

The logical flow from CFD solution to actionable insight involves specific post-processing steps.

Diagram Title: CFD Post-Processing Workflow for Bioreactor Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential research reagents and materials for experimental validation of mixing dynamics.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function in Mixing Analysis |

|---|---|

| Phenolphthalein Indicator Solution (1% in ethanol) | pH-sensitive colorimetric tracer for decolorization mixing time experiments. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) or Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) Tracer (1M) | Provides the pH shift for indicator reaction; pulse input for mixing characterization. |

| Non-Invasive pH Probes (e.g., Optical pH Spots) | Enable monitoring at multiple internal locations without disrupting flow. |

| Conductivity Tracer (e.g., NaCl Solution) | Alternative tracer for conductivity probes; useful for non-pH-sensitive cultures. |

| Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) Seeding Particles | Hollow glass or polymer spheres for experimental flow field validation via PIV. |

| Computational Mesh Generation Software (e.g., ANSYS Mesher, snappyHexMesh) | Creates the discrete spatial domain for CFD simulation from bioreactor geometry. |

Quantifying Mixing Time (θ_mix) from Simulation

Mixing time is a critical scale-up parameter. The following table compares common methods for extracting θ_mix from transient CFD data.

Table 3: Methods for Determining Mixing Time from Simulation Data

| Method | Description | Calculation from Simulation Data | Advantages/Limitations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold Method | Time for all monitor points to reach ±X% of final mean. | `θ_mix = max( t | | Ci(t) - C∞ | / C_∞ ≤ 0.05 )` | Intuitive; directly comparable to experiment. Sensitive to probe number/location. |

| Variance Decay Method | Time for domain variance to decay to a target fraction. | θ_mix = t such that σ²(t) / σ²(0) = 0.05 |

Holistic, uses full-field data. Computationally more intensive. | ||

| Flow Field Characteristic | Based on turbulent flow parameters (macro-mixing). | θ_mix ∝ (Energy Dissipation Rate, ε)^{-1/3} |

Useful for early-stage estimation. Does not account for initial conditions. |

Visualizing Mixing Pathways

Understanding how material travels from the point of addition (e.g., feed pipe) to critical regions (e.g., impeller, cell retention zone) is key.

Diagram Title: Key Material Transport Pathways in a Stirred Bioreactor

Solving Common CFD Challenges and Optimizing Bioreactor Design for Uniformity

Diagnosing Convergence Issues and Ensuring Solution Accuracy

This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation for bioreactor gradient analysis research, provides an in-depth guide to diagnosing numerical convergence issues and verifying solution accuracy. Accurate CFD simulation of momentum, mass, and species transport is critical for predicting gradients in dissolved oxygen, nutrients, and metabolites within bioreactors, directly impacting cell culture viability and biopharmaceutical product quality.

Core Convergence Issues in Bioreactor CFD

Convergence failure indicates that the numerical solution has not reached a steady state or a periodic state within the defined iterative framework. For bioreactor simulations, common issues stem from complex multiphase flows, steep scalar gradients, and turbulent-chemistry interactions.

Table 1: Quantitative Convergence Criteria & Typical Target Values

| Criterion | Description | Typical Target for Bioreactors | Strict Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residual Norm | L2 Norm of equation imbalance | Reduce by 3-4 orders of magnitude | Reduce by 6 orders |

| Scalar Monitor | Point value (e.g., DO at probe) | Change < 0.1% over 100 iterations | Change < 0.01% |

| Global Mass Balance | (In - Out) / In | < 0.5% | < 0.1% |

| Force Coefficients | Drag/Lift on impeller | Change < 0.5% per revolution | Change < 0.1% |

Diagnostic Methodologies

Residual Analysis Protocol

Objective: Identify the equation(s) causing divergence. Procedure:

- Run simulation for 100-200 iterations after suspected stall.

- Export residual history for continuity, momentum (X, Y, Z), k, epsilon, and species transport equations.

- Plot log10(Residual) vs. Iteration for each equation.

- Diagnosis: An upward trend in any residual indicates instability. A flat line at a high value indicates a modeling or discretization error.

- Action: Isolate the problematic physics (e.g., turbulence model, species source term) and apply targeted remedies.