From Primary Metabolism to Powerful Medicines: Harnessing Biosynthetic Building Blocks for Drug Discovery

This article explores the critical role of biosynthetic building blocks derived from primary metabolism in the creation of bioactive natural products.

From Primary Metabolism to Powerful Medicines: Harnessing Biosynthetic Building Blocks for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of biosynthetic building blocks derived from primary metabolism in the creation of bioactive natural products. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis of the foundational principles, methodological applications, and current challenges in the field. We examine how primary metabolites like amino acids, acyl-CoAs, and nucleotides serve as precursors for complex secondary metabolites with therapeutic potential. The content covers advanced strategies in synthetic biology and combinatorial biosynthesis for optimizing production, discusses analytical and computational tools for pathway validation, and synthesizes key takeaways to outline future directions for biomedical and clinical research, offering a holistic perspective on this essential interface of metabolism and medicine.

The Chemical Blueprint of Life: Exploring Primary Metabolites as Biosynthetic Precursors

The traditional dichotomy between primary and secondary metabolism is a concept rooted in the historical development of biochemistry. Albrecht Kössel's 1891 definition separated the universal, "necessary for life" primary metabolites from the "random or not necessary" secondary metabolites [1]. However, contemporary research reveals this distinction to be increasingly artificial, demonstrating instead a deeply integrated metabolic continuum where primary metabolism supplies the essential building blocks for the vast chemical diversity of secondary metabolites [1] [2]. This in-depth technical guide explores the fundamental linkages between these metabolic domains, framing them within advanced biosynthetic building blocks research critical for drug discovery and development. For researchers and scientists, understanding this interface is paramount for harnessing the biosynthetic potential of living organisms, particularly for the sustainable production of valuable natural products with pharmacological activity [3] [4].

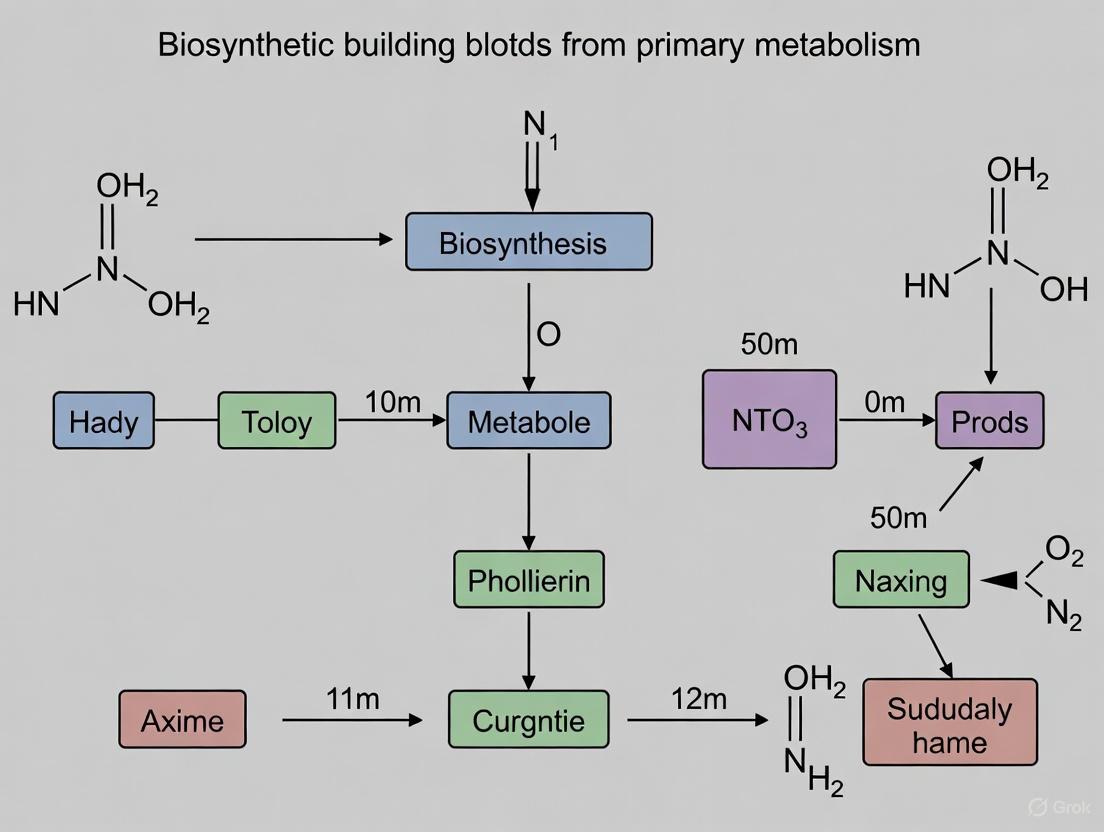

The following core diagram illustrates the foundational relationship between primary metabolic pathways and the major classes of secondary metabolites they support.

Diagram 1: Biosynthetic Link Between Primary and Secondary Metabolism.

Defining the Metabolic Domains

Comparative Analysis of Metabolic Types

The following table summarizes the defining characteristics of primary and secondary metabolites, highlighting their distinct yet interconnected roles.

Table 1: Characteristic Differences Between Primary and Secondary Metabolites [5] [6]

| Basis for Comparison | Primary Metabolites | Secondary Metabolites |

|---|---|---|

| Definition & Role | Directly involved in growth, development, and reproduction; essential for survival [6]. | Not directly involved in primary processes; essential for ecological interactions (defense, competition) [5] [7]. |

| Universal Presence | Found in all living organisms without exception [1] [5]. | Distribution is often species-specific or restricted to certain phylogenetic groups [5]. |

| Production Phase | Produced during the growth phase (trophophase) [6]. | Typically produced during the stationary phase (idiophase) or in response to stress [7] [6]. |

| Chemical Diversity | Limited diversity; includes universal macromolecules (proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates, lipids) [6]. | Extremely high chemical diversity; includes alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics, and glucosinolates [1] [7]. |

| Quantity Produced | Produced in large quantities [6]. | Produced in small quantities [6]. |

| Function in Research | Used in various industries (food, biofuels) [6]. | Valued for pharmacological activities; used in drug development and agrochemicals [3] [5]. |

The Building Block Paradigm: From Primary Precursors to Secondary Products

Primary metabolism generates a pool of core metabolites that serve as universal biosynthetic building blocks. These precursors are funneled into specialized secondary metabolic pathways, often via gatekeeping enzymes that mark the transition point between the two metabolic domains [8]. The major building blocks and their secondary product families are summarized below.

Table 2: Primary Metabolite Building Blocks and Their Secondary Product Families [5] [7] [2]

| Primary Metabolite Building Block | Biosynthetic Origin | Major Classes of Secondary Metabolites | Key Examples (Pharmacological Use) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA / Intermediates from Glycolysis & MEP Pathway | Krebs Cycle, Glycolysis, Plastidial MEP Pathway [1] [7] | Terpenoids (Monoterpenes, Diterpenes, Triterpenes) | Paclitaxel (anticancer) [5], Artemisinin (antimalarial) [7], Gibberellins (plant hormone) [1] |

| Amino Acids (e.g., Tryptophan, Tyrosine, Lysine, Aspartate) | Nitrogen Assimilation & Primary Metabolism [5] | Alkaloids (various sub-classes) | Morphine (analgesic) [5], Vincristine (anticancer) [1] [5], Nicotine (insecticide) [5] |

| Phenylalanine / Shikimate Pathway Intermediates | Shikimate Pathway [5] | Phenolic Compounds (Flavonoids, Lignin, Tannins) | Flavonoids (antioxidants) [7] [6], Salicylic Acid (anti-inflammatory) [5], Lignin (structural polymer) [5] |

| β-Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (β-NAD) | Nucleotide Metabolism [8] | Novel β-NAD-derived Natural Products | Altemicidin, SB-203208 (isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitor) [8] |

Advanced Experimental Protocols for Elucidating Metabolic Links

Protocol 1: Gene Cluster Activation and Metabolite Identification in Bacteria

This methodology details the process of identifying novel secondary metabolites derived from primary metabolic building blocks, as demonstrated in the discovery of β-NAD-derived natural products [8].

Objective: To elucidate the biosynthetic pathway of unusual secondary metabolites with unknown primary metabolite precursors.

Workflow Overview:

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Novel Pathway Elucidation.

Detailed Methodology:

- Resistance Gene-Guided Genome Mining: Identify a Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (BGC) of interest through genome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis, focusing on clusters with low homology to known systems [8].

- Heterologous Expression: Clone the entire BGC into a suitable microbial host, such as Streptomyces lividans TK21, to activate the expression of the pathway [8].

- Gatekeeping Enzyme Identification via Single Gene Expression: Construct single gene expression strains for each uncharacterized gene in the cluster. Subject the culture extracts to untargeted metabolomics analysis (e.g., LC-MS) under various analytical conditions to identify accumulating intermediates [8].

- Intermediate Structure Elucidation: Isolate the accumulating metabolite of high polarity. Use NMR spectroscopy and high-resolution mass spectrometry to determine its chemical structure, which may reveal an unexpected primary metabolite origin [8].

- Substrate Screening & In Vitro Reconstitution: Based on the intermediate's structure, hypothesize potential primary metabolite substrates (e.g., β-NAD, S-adenosylmethionine). Incubate recombinant gatekeeping enzyme with candidate substrates and co-factors to validate the initial enzymatic transformation [8].

- Downstream Pathway Reconstitution: Express and purify the remaining biosynthetic enzymes. Reconstitute the entire pathway in vitro to confirm the sequence of reactions leading to the final natural product and characterize the function of each novel enzyme [8].

Protocol 2: Multi-Omics Interrogation of Plant Metabolic Reprogramming

This protocol is used to decode the interplay between primary and secondary metabolism in plants in response to abiotic stress or elicitors [9] [7].

Objective: To understand the metabolic reprogramming and transcriptional regulation that links primary metabolic flux to the biosynthesis of specialized secondary metabolites under stress conditions.

Detailed Methodology:

- Controlled Stress/Elicitor Application: Subject model plants (e.g., alfalfa, white clover) or non-model medicinal species (e.g., Epimedium pubescens, Polygonatum kingianum) to defined abiotic stress (e.g., UV-B, drought, salinity) or treat with signaling molecules (e.g., melatonin, diethyl aminoethyl hexanoate - DA-6) or nanoparticles (Selenium NPs) [1] [9].

- Integrated Sample Collection: Harvest plant tissues at multiple time points post-treatment for parallel transcriptomic, metabolomic, and physiological analyses.

- Transcriptome Sequencing & Analysis: Perform RNA-seq on test and control samples. Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs), with a focus on transcription factors (e.g., WRKY) and genes encoding core biosynthetic enzymes for both primary and secondary metabolism [9] [7].

- Non-Targeted Metabolome Profiling: Analyze the same tissue extracts using GC-MS and LC-MS platforms. Identify and quantify Differentially Accumulated Metabolites (DAMs), covering both primary (sugars, amino acids, organic acids) and secondary (alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics) metabolites [9].

- Multi-Omics Data Integration: Perform correlation network analysis to link gene expression patterns with metabolite accumulation. Construct co-expression networks to identify key regulatory nodes and potential metabolons (enzyme complexes) [4]. This step is crucial for mapping primary metabolic shifts to the induction of specific secondary metabolic pathways.

- Functional Validation: Clone and characterize candidate genes (e.g., OsDUF868.12 for salt tolerance) via overexpression and/or knockdown studies. Validate enzyme function in vitro and confirm metabolite production in engineered systems [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Technologies for Metabolic Link Research

| Research Reagent / Technology | Function & Application in Metabolic Research |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Precursors (e.g., ¹³C-Glycerol, ¹âµN-Aspartate, Dâ‚‚O) | Used in isotopic labelling experiments to trace the incorporation of primary metabolites into secondary metabolic scaffolds, establishing definitive biosynthetic routes [8]. |

| Heterologous Expression Systems (e.g., Streptomyces lividans, S. cerevisiae, Plant Hairy Root Cultures) | Serve as programmable biofactories to express silent or complex BGCs, produce problematic intermediates, and elucidate pathways without interference from the native host's metabolism [8] [2]. |

| Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) Predictors (e.g., antiSMASH, PRISM) | Bioinformatics tools for the in silico identification of genomic loci encoding secondary metabolic pathways, providing the first step in linking genes to chemistry [3]. |

| Gatekeeping Enzymes (e.g., Terpene Synthases, SbzP-like Aminotransferases, Polyketide Synthases) | Key enzymatic targets for research as they catalyze the first committed step from primary metabolic pools into secondary pathways; their study reveals novel biochemical transformations [8]. |

| Signaling Molecule Elicitors (e.g., Melatonin, Methyl Jasmonate, Hydrogen Sulfide, Nitric Oxide) | Used to mimic stress conditions and activate the endogenous regulatory networks that control the flux from primary to secondary metabolism, boosting the production of target compounds [1] [7]. |

| Metabolon Engineering Tools (CRISPR-Cas, Synthetic Scaffolds) | Emerging approaches to spatially organize sequential enzymes of a pathway to enhance channeling of primary precursors into desired secondary products, minimizing off-target effects and increasing yield [4]. |

| 1-(2,3-Dichlorphenyl)piperazine | 1-(2,3-Dichlorphenyl)piperazine, CAS:41202-77-1, MF:C10H12Cl2N2, MW:231.12 g/mol |

| Gly6 | Gly6, CAS:3887-13-6, MF:C12H20N6O7, MW:360.32 g/mol |

The historical view of secondary metabolism as a dispensable adjunct to primary metabolism has been conclusively overturned. Modern research underscores a deeply integrated system where primary metabolites serve as essential building blocks for a vast arsenal of specialized compounds critical for an organism's survival and ecological interaction [1] [7]. For drug development professionals, the implications are profound: understanding the genetic and enzymatic links that govern the flow of carbon and nitrogen from primary to secondary metabolism provides unprecedented control over the biosynthetic machinery.

Future research will be dominated by efforts to decode the spatial organization of metabolism within cells, understanding how metabolons (transient enzyme complexes) enhance pathway efficiency [1] [4]. The integration of artificial intelligence and deep learning will accelerate the prediction of BGC functions and the design of optimized enzymes [3] [4]. Furthermore, the discovery of entirely new classes of building blocks, such as β-NAD [8], suggests that our current knowledge of the metabolic inventory is still incomplete. Continued exploration of this interface, powered by the advanced experimental and computational tools outlined in this guide, promises to unlock a new generation of natural product-based therapeutics and sustainable bioprocesses.

Within every living cell, a concise set of primary metabolites serves as the universal chemical feedstock for life's diverse molecular structures. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these core building blocks—their biosynthetic origins and the tools to study them—is fundamental to advancing metabolic engineering and natural product discovery. This guide provides a technical examination of the essential primary metabolic pathways, detailing the key metabolites they produce, the experimental methodologies used to elucidate their flow, and the computational frameworks employed to navigate biosynthetic networks. Framed within the context of contemporary biosynthetic building block research, this resource serves as a toolkit for manipulating metabolic pathways to innovate therapeutic development [10] [11].

The Core Primary Metabolic Pathways and Their Products

Primary metabolism converts simple precursors into the essential building blocks for cellular machinery. The following table summarizes the major pathways and their key metabolite outputs.

Table 1: Essential Primary Metabolic Pathways and Key Building Blocks

| Metabolic Pathway | Key Precursor Metabolites | Primary Building Blocks Produced | Derived Product Classes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis & Gluconeogenesis | Glucose, Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) [10] | Pyruvate, Glycerol-1-phosphate [11], 3-Phosphoglycerate [11] | Sugars, Polysaccharides, Glycerol backbone of lipids [11] |

| Shikimate Pathway | Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), Erythrose 4-Phosphate (E4P) [10] | Chorismate [10], Shikimate [10] | Aromatic Amino Acids (Phenylalanine, Tyrosine, Tryptophan) [10], Plant-derived antibiotics & pigments [10] |

| Tri-carboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle | Acetyl-CoA | α-Ketoglutarate, Succinyl-CoA, Oxaloacetate | Amino Acids (Glutamate family), Heme, Tetrapyrroles |

| Mevalonate (MVA) / Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathways | Acetyl-CoA [12] | Isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), Dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) [12] | Terpenoids, Steroids [13] |

| Amino Acid Biosynthesis | Various intermediates from Glycolysis, TCA, Shikimate | 20 Proteinogenic Amino Acids [13] [10] | Non-ribosomal peptides (NRPs), Alkaloids [13] |

The following diagram illustrates the interconnectedness of these primary metabolic pathways and the key building blocks they generate.

Experimental Methodologies for Pathway Elucidation

Elucidating the flow of metabolites from primary building blocks to complex products requires a suite of sophisticated experimental protocols.

Genome Mining and Heterologous Expression

The identification of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) is the foundational first step. antiSMASH (antibiotics and Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell) is the predominant tool for BGC identification in genomic data [14] [15]. Following identification, heterologous expression is used to validate BGC function. The protocol involves cloning the entire BGC into a model host organism, such as Streptomyces lividans, which does not produce the compound natively. Successful production of the target metabolite in the heterologous host confirms the identity and functionality of the BGC, as demonstrated in the elucidation of the moenomycin A pathway [16].

Metabolite Profiling and Isotopic Labeling

Metabolite profiling using Mass Spectrometry (MS) provides a snapshot of the metabolic state of a system. Coupling MS with separation techniques like chromatography (LC-MS/MS) allows researchers to separate, detect, and quantify thousands of metabolites in a single run [15]. For tracing the incorporation of primary metabolites into complex pathways, isotopic labeling is indispensable. The methodology involves feeding cells with a (^{13}\text{C})- or (^{14}\text{C})-labeled precursor (e.g., (^{13}\text{C})-glucose). The fate of the labeled atom is then tracked using NMR or MS, allowing for the precise mapping of biosynthetic pathways, as historically used to determine the non-mevalonate origin of the isoprenoid chain in moenomycin [16].

Integrated Paired Omics Analysis

A powerful contemporary approach is the systematic integration of genomic and metabolomic data. The Paired Omics Data Platform (PoDP) is a community resource that facilitates the linking of public metabolomics datasets to their genomic origins [15]. The workflow involves:

- Data Generation: Sequencing the genome and acquiring MS/MS metabolomic data from the same biological sample.

- Data Deposition: Submitting genomic data to repositories like GenBank and metabolomic data to platforms like GNPS-MassIVE.

- Data Linking: Registering the paired datasets in the PoDP with minimal metadata, creating standardized genome-metabolome links.

- Correlation Analysis: Using computational tools to correlate the presence or expression of specific BGCs (the genotype) with the detection of specific molecular families in MS data (the chemotype), a process known as metabologenomics [14] [15].

Computational and Bioinformatics Toolkits

The complexity of metabolic networks necessitates advanced computational tools for prediction and analysis.

Retrobiosynthesis Prediction with Deep Learning

BioNavi-NP is a deep learning-driven tool that predicts biosynthetic pathways for natural products in a retrosynthetic manner. It uses transformer neural networks trained on general organic and biosynthetic reactions to predict plausible precursor molecules for a target compound. Through an AND-OR tree-based planning algorithm, it then iterates this process to map multi-step routes back to fundamental building blocks from the AA/MA, MVA/MEP, CA/SA, and AAs pathways [13]. This tool represents a significant advance over conventional rule-based approaches, demonstrating a 1.7-fold higher accuracy in recovering reported building blocks [13].

Large-Scale Genomic Analysis

To explore biosynthetic diversity across thousands of genomes or metagenomes, tools like BiG-SCAPE (Biosynthetic Gene Similarity Clustering And Prospecting Engine) are essential. BiG-SCAPE performs large-scale sequence similarity network analysis of BGCs, grouping them into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) based on a combined metric of Pfam domain content, synteny, and sequence identity [14]. This allows researchers to prioritize BGCs for discovery based on their novelty or distribution. For deeper phylogenetic analysis, CORASON (CORe Analysis of Syntenic Orthologues to prioritize Natural product gene clusters) can be used to elucidate evolutionary relationships within and across GCFs [14].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Pathway Analysis

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH [14] [15] | Identification & annotation of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) in genomic data. | Rule-based, supports a wide range of BGC classes (PKS, NRPS, RiPPs, etc.). |

| BioNavi-NP [13] | De novo prediction of biosynthetic pathways for natural products. | Deep learning (transformer) model; 1.7x more accurate than rule-based methods. |

| BiG-SCAPE & CORASON [14] | Large-scale comparative analysis & phylogenomics of BGCs. | Groups BGCs into families (GCFs); elucidates evolutionary relationships. |

| Paired Omics Data Platform (PoDP) [15] | Community resource for linking genomic and metabolomic datasets. | Facilitates metabologenomics; enables FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles. |

| Uniformly (^{13}\text{C})-labeled Internal Standards [17] | Normalization and quantitative analysis in spatial metabolomics. | Cost-effective; addresses physico-chemical complexity of metabolite detection. |

| Heterologous Host Systems (e.g., S. lividans) [16] | Expression of BGCs in a tractable, surrogate organism. | Confirms BGC function; enables production of novel derivatives. |

| Z-D-Chg-OH | Z-D-Chg-OH, CAS:69901-85-5, MF:C16H21NO4, MW:291.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| H-Lys(Z)-OMe.HCl | H-Lys(Z)-OMe.HCl, CAS:27894-50-4, MF:C15H23ClN2O4, MW:330.81 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The synergistic use of these experimental and computational tools creates a powerful workflow for discovering and engineering metabolic pathways, as visualized below.

Plant secondary metabolism represents a sophisticated biochemical landscape where simple building blocks from primary metabolism are transformed into a vast array of specialized compounds. Terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenolics constitute three major architectural classes of these specialized metabolites, each with distinct biosynthetic origins and structural frameworks [18]. These compounds play crucial ecological roles in plant defense, communication, and adaptation while offering immense therapeutic potential for drug development [19] [18]. Understanding their biosynthetic blueprints—how fundamental carbon skeletons are assembled from primary metabolic precursors—provides the foundational knowledge necessary for manipulating their production through metabolic engineering and synthetic biology approaches [20] [21]. This review systematically examines the architectural principles governing the formation of these valuable compounds, focusing on their metabolic origins, structural diversification, and experimental characterization methodologies relevant to pharmaceutical research and development.

Biosynthetic Building Blocks and Pathways

Metabolic Origins and Carbon Skeletons

The architectural diversity of plant secondary metabolites arises from the strategic diversion of primary metabolic intermediates into specialized biosynthetic pathways. Table 1 summarizes the core building blocks and basic carbon skeletons that define each major class of specialized metabolites.

Table 1: Architectural Foundations of Major Plant Specialized Metabolite Classes

| Metabolite Class | Primary Metabolic Building Blocks | Basic Carbon Skeleton | Representative Structures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids [19] [21] | Acetyl-CoA (MVA pathway); Pyruvate & G3P (MEP pathway) | C5 (Isoprene unit); C10, C15, C20, C30, C40 chains | Monoterpenes (e.g., limonene), Sesquiterpenes (e.g., artemisinin), Diterpenes (e.g., paclitaxel) |

| Phenolics [19] [18] | Phosphoenolpyruvate & Erythrose-4-phosphate | C6-C3 (Phenylpropanoid); C6-C1 (Benzoic acid); C6-C2-C6 (Flavonoid) | Simple phenolics, Flavonoids, Lignans, Tannins |

| Alkaloids [18] | Various amino acids (e.g., tyrosine, tryptophan, lysine, ornithine) | Heterocyclic structures containing nitrogen | Indole alkaloids (e.g., mitragynine), Isoquinoline alkaloids (e.g., morphine) |

The biosynthetic grid of plant specialized metabolism originates from three central metabolic hubs: the mevalonate (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways for terpenoids; the shikimic acid pathway for phenolics; and various amino acid metabolic pathways for alkaloids [19] [18]. The MVA pathway, conserved in eukaryotes and some archaea, utilizes acetyl-CoA to produce the universal five-carbon terpenoid precursors isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) [20] [21]. Concurrently, the MEP pathway, predominant in prokaryotes and plant plastids, generates IPP and DMAPP from pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) [21]. For phenolic compounds, the shikimate pathway bridges carbon metabolism from phosphoenolpyruvate (glycolysis) and erythrose-4-phosphate (pentose phosphate pathway) to aromatic amino acids, which subsequently serve as precursors for diverse phenolic skeletons [18]. Alkaloid biosynthesis draws primarily on nitrogen-containing amino acid precursors such as tyrosine, tryptophan, lysine, and ornithine, which undergo decarboxylation and complex rearrangement to form characteristic heterocyclic structures [18].

Pathway Visualization and Metabolic Cross-Talk

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected biosynthetic routes from primary metabolic precursors to the architectural cores of terpenoids, phenolics, and alkaloids.

This metabolic map reveals the strategic diversion of primary metabolic intermediates into the specialized metabolic pathways. The MVA and MEP pathways converge on the synthesis of IPP and DMAPP, the universal C5 building blocks for terpenoid diversity [20] [21]. The shikimate pathway provides the phenylpropanoid backbone (C6-C3) that serves as the foundation for phenolic compound structural elaboration [19] [18]. Meanwhile, multiple branches of amino acid metabolism give rise to nitrogen-containing heterocyclic scaffolds characteristic of alkaloids [18]. This metabolic architecture enables plants to generate immense chemical diversity from a limited set of primary metabolic precursors.

Experimental Methodologies for Biosynthetic Pathway Characterization

Transcriptome Mining and Heterologous Expression

Elucidating complete biosynthetic pathways for plant secondary metabolites requires integrated experimental approaches. Transcriptome mining has emerged as a powerful initial step for identifying candidate biosynthetic genes in non-model plants with rich specialized metabolomes [22]. The standard workflow begins with RNA extraction from metabolically active tissues, followed by high-throughput sequencing using both short-read (Illumina) and long-read (Oxford Nanopore) technologies to ensure comprehensive transcript coverage [22]. The resulting sequences are assembled into a reference transcriptome and annotated using tools like InterProScan and BLAST against curated databases (e.g., SwissProt) to identify genes encoding key biosynthetic enzymes based on conserved domains and functional annotations [22].

Following gene identification, heterologous expression in tractable host systems enables functional characterization of putative biosynthetic enzymes. Common expression platforms include Escherichia coli for prokaryotic enzymes and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) or Nicotiana benthamiana for eukaryotic enzymes requiring post-translational modifications or subcellular compartmentalization [20] [22]. For functional screening, candidate genes are typically cloned into appropriate expression vectors and introduced into the host system, often with rate-limiting enzymes from precursor pathways (e.g., HMGR from the MVA pathway or DXS from the MEP pathway) to enhance precursor availability and product detection [22]. Metabolite production is then analyzed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) by comparing retention times and mass spectra with authentic standards [23] [22].

Metabolic Engineering and Pathway Optimization

Once key biosynthetic enzymes are characterized, metabolic engineering approaches enable pathway optimization for enhanced metabolite production. Strategic interventions include modulating the expression of rate-limiting enzymes through strong promoters, engineering feedback-insensitive enzyme variants to circumvent endogenous regulation, and implementing dynamic control systems to balance metabolic flux [20] [24]. In microbial systems, this often involves the overexpression of terpene synthases coupled with enhancement of the MVA or MEP pathways to increase precursor supply [20]. In plant systems, Agrobacterium-mediated transformation has been successfully employed to engineer terpenoid biosynthesis in tobacco hairy roots, demonstrating the metabolic plasticity of plant systems for producing diverse glycosylated terpenoid derivatives [20] [24].

Recent advances have incorporated computational and artificial intelligence technologies for the rational design of high-performance cell factories, enabling predictive optimization of enzyme combinations and cultivation parameters for maximizing terpenoid yields [20]. Additionally, directed evolution approaches applied to terpene synthases have successfully overcome catalytic efficiency limitations, as demonstrated by a 30% increase in artemisinin biosynthesis through optimization of sesquiterpene cyclase activity [24].

Research Reagent Solutions for Biosynthetic Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Secondary Metabolite Biosynthesis Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cloning & Expression Vectors | pHREAC plant expression vector [22] | Heterologous expression in Nicotiana benthamiana | Gateway-compatible vector for rapid cloning of biosynthetic genes |

| Enzyme Substrates | Farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) [22]; Geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) [21] | In vitro enzyme assays | Core substrates for sesquiterpene and monoterpene synthases, respectively |

| Analytical Standards | Limonene, α-pinene, caryophyllene, R-linalool [22]; Mitragynine, 7-hydroxymitragynine [23] | Metabolite identification and quantification | GC-MS and LC-MS standards for compound identification and quantification |

| Critical Enzymes | HMGR (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase) [22]; DXS (1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase) [20] | Metabolic pathway engineering | Rate-limiting enzymes in MVA and MEP pathways, respectively; enhance precursor flux |

| Chromatography Materials | C18 columns [25]; UHPLC systems [25]; GC-MS systems [22] | Metabolite separation and analysis | High-resolution separation and detection of specialized metabolites |

Structural Diversification and Functional Consequences

Enzymatic Modifications and Decorative Reactions

The fundamental carbon skeletons described in Section 2 undergo extensive structural elaboration through various enzyme-catalyzed modifications that significantly expand their chemical diversity and functional properties. For terpenoids, the basic scaffolds produced by terpene synthases (TPS) are further modified by cytochrome P450 oxygenases (CYP450s) that introduce oxygen functional groups through hydroxylation, epoxidation, and other oxidative transformations [21]. These modifications dramatically alter the biological activity, solubility, and volatility of the parent terpenoid scaffolds.

Phenolic compounds experience perhaps the most diverse array of decorative modifications, including glycosylation (addition of sugar moieties), acylation (addition of acyl groups), prenylation (addition of prenyl chains), and methylation [19]. These modifications influence the reactivity, bioavailability, and subcellular localization of phenolic compounds. For example, glycosylation of flavonoids enhances their water solubility and storage in vacuoles, while acylation can alter their antioxidant properties and interaction with cellular membranes [19].

Alkaloids similarly undergo extensive functionalization through oxidation, reduction, methylation, and glycosylation reactions that modulate their biological activity and physicochemical properties [23] [18]. The dose-dependent bioactivity of alkaloids makes these structural modifications particularly significant for their pharmacological applications, where subtle changes to molecular structure can dramatically alter potency and selectivity [18].

Structure-Function Relationships in Bioactivity

The structural diversity within each metabolite class directly influences their biological functions and therapeutic potential. For phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity is strongly influenced by molecular structure, particularly the number and position of hydroxyl groups on the aromatic rings and the presence of extended conjugation systems that stabilize the resulting phenoxyl radicals [19] [18]. The redox chemistry of phenolics enables them to function as both antioxidants and pro-oxidants depending on concentration and cellular context, contributing to their roles in stress protection and therapeutic applications [19].

In terpenoids, structural features such as carbon skeleton type, stereochemistry, and functional groups determine their biological activities and ecological functions [19] [21]. Monoterpenes with volatile properties serve as ecological signals in plant-insect interactions, while more complex diterpenes and triterpenes with higher molecular weights and increased functionalization often exhibit potent pharmacological activities, as demonstrated by the anticancer drug paclitaxel (diterpene) and the immunomodulator ginsenoside (triterpene) [20] [18].

For alkaloids, the presence of basic nitrogen atoms incorporated into heterocyclic ring systems enables interactions with neurotransmitter receptors and ion channels, underlying their diverse pharmacological effects on the nervous system [18]. The spatial arrangement of functional groups around these nitrogen-containing scaffolds creates complementary surfaces for binding to biological targets, explaining why subtle stereochemical differences can dramatically alter potency and selectivity [23] [18].

The architectural classes of terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenolics represent nature's sophisticated solution to generating chemical diversity from a limited set of primary metabolic building blocks. The systematic diversion of acetyl-CoA, amino acids, and sugar phosphates into specialized metabolic pathways creates distinct carbon skeletons that are further elaborated through enzyme-catalyzed modifications to produce immense structural variety [19]. This chemical diversity directly enables the multifunctional bioactivities that make these compounds invaluable as pharmaceutical agents, nutraceuticals, and fragrance compounds [18].

Understanding these architectural principles provides the foundation for rational manipulation of secondary metabolic pathways through metabolic engineering and synthetic biology approaches [20] [24]. Current challenges in the field include overcoming metabolic bottlenecks in heterologous production systems, understanding the regulatory networks that control pathway flux in native producers, and elucidating the structure-activity relationships that connect molecular architecture to biological function [20] [24]. Future research directions will likely focus on integrating multi-omics data with machine learning approaches to predict pathway regulation and enzyme function, enabling more precise engineering of production platforms for high-value natural products [20]. Additionally, exploring the ecological and evolutionary drivers of structural diversity will continue to provide insights into the selective pressures that shape these complex metabolic networks in plants [19]. As these architectural principles become increasingly well-understood, they will accelerate the development of sustainable production systems for plant-derived pharmaceuticals and other valuable specialized metabolites.

Plants have long served as a cornerstone of both traditional and modern medicine, representing one of the major reservoirs of medicinal compounds [4]. The evolution of natural product discovery spans from ancient practices of using plant extracts to the contemporary era of pathway elucidation, where researchers decode the complex biosynthetic routes nature uses to assemble these valuable compounds. This journey reflects a fundamental shift from simply isolating compounds to comprehensively understanding and engineering their production systems.

This evolution is particularly significant when framed within the context of biosynthetic building blocks from primary metabolism. Primary metabolites—including amino acids, sugars, vitamins, and organic acids—are essential for growth, development, and reproduction, acting as the foundational carbon and nitrogen sources for cellular processes [26]. In contrast, secondary metabolites (also called specialized or natural products) are not directly involved in essential physiological processes but play crucial ecological roles and often exhibit remarkable pharmacological activities [8] [27].

The connection between these metabolic realms is fundamental: specialized metabolites are metabolically derived from the primary metabolite pool and assembled by distinct enzyme families [8]. Typical natural product classes like terpenoids, polyketides, or non-ribosomal peptides are derived from oligoprenyl diphosphates, activated C2-building blocks like malonyl-CoA, or amino acids [8]. Understanding how nature converts these primary metabolite building blocks into complex chemical frameworks through dedicated biosynthetic machinery represents the modern frontier of natural product discovery.

The Historical Foundation: Plant Extracts and Early Isolation Techniques

Traditional approaches to natural product discovery relied heavily on the bioactivity-guided fractionation of plant extracts. Early natural products research focused on isolating active compounds from medicinal plants used in traditional healing systems worldwide. This process typically involved harvesting plant material, creating crude extracts using various solvents, and then using pharmacological screening to identify bioactive fractions for further purification.

These classical biochemical methods included activity assays of crude protein extracts, isotope labeling of metabolites, synthetic oligodeoxynucleotide hybridization probes, homology-based cloning, and expressed sequence tags library sequencing [28]. For instance, radioisotope-labeled feeding approaches were successfully employed in elucidating pathways like galanthamine biosynthesis [28]. While these methodologies provided the foundation for our understanding of plant natural products, they were often labor-intensive and provided limited insight into the complete biosynthetic pathways or the genetic basis of production.

The major limitation of these early approaches was their inability to efficiently connect the chemical structures of natural products with the genetic information responsible for their biosynthesis. Each discovered compound represented a piece of the puzzle, but the complete picture of how plants transformed simple primary metabolites into complex molecular architectures remained largely elusive.

The Modern Revolution: Multi-Omics and Pathway Elucidation

The emergence of next-generation sequencing (NGS) in the late 2000s revolutionized the natural products landscape, providing comprehensive omics datasets that transformed pathway discovery from a piecemeal process to a systems-level science [28]. This shift enabled researchers to move beyond simply identifying what compounds plants produce to understanding how they produce them at a genetic, enzymatic, and regulatory level.

Core Omics Technologies in Pathway Elucidation

Modern pathway elucidation leverages multiple high-throughput technologies that generate vast datasets for comprehensive analysis [28] [29]. The table below summarizes the key omics technologies and their specific applications in natural product discovery.

Table 1: Multi-Omics Technologies in Natural Product Pathway Discovery

| Technology | Data Output | Application in Pathway Discovery | Representative Elucidated Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequences, gene content, chromosomal organization | Gene cluster identification, synteny analysis, phylogenetic distribution of pathways | Vinblastine, colchicine, strychnine [28] |

| Transcriptomics | Gene expression levels, co-expression networks | Identification of coordinately regulated genes, correlation with metabolite abundance | Etoposide, colchicine, strychnine, triterpene [28] |

| Metabolomics | Metabolite profiles, chemical structures, abundances | Correlation of metabolite accumulation with gene expression, identification of pathway intermediates | Galanthamine, monoterpene indole alkaloids [28] |

| Single-Cell Omics | Cell-type specific expression and metabolite data | Resolution of spatial organization of pathways within tissues | Various pathways at cell-type resolution [28] |

Computational Tools for Data Integration

The enormous volume and intricacy of genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics data require robust tools for data management and mining [28]. These computational approaches have become indispensable for extracting meaningful insights from large, complex, and high-dimensional datasets.

Table 2: Computational Approaches for Biosynthetic Pathway Elucidation

| Analytical Approach | Specific Tools/Methods | Function in Pathway Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Co-expression Analysis | Pearson correlation, self-organizing maps | Identifies genes with coordinated expression across conditions |

| Homology-Based Discovery | OrthoFinder, KIPEs, BLAST search | Finds evolutionarily related genes with known functions |

| Gene Cluster Identification | ClusterFinder, antiSMASH | Identifies physically grouped genes in genomes |

| Machine Learning | Various supervised ML algorithms | Predicts gene functions and pathway components from patterns |

Experimental Workflows: From Gene Discovery to Pathway Validation

The elucidation of complete biosynthetic pathways requires the integration of multiple experimental strategies in a systematic workflow. The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive multi-omics approach that has become standard in the field.

Figure 1. Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow for Pathway Elucidation. This flowchart illustrates the comprehensive approach from sample collection to complete pathway reconstitution, highlighting the integration of multiple data types and validation strategies.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Heterologous Expression Systems

Heterologous expression involves introducing candidate biosynthetic genes into surrogate host organisms to test their function. The most common systems include:

- Escherichia coli bacteria: Ideal for expressing prokaryotic genes and performing enzymatic assays with purified proteins [28].

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast: Suitable for eukaryotic genes requiring post-translational modifications and for pathway reconstruction [28].

- Nicotiana benthamiana tobacco: Used for Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression, allowing rapid co-expression of multiple plant genes without stable transformation [28].

The Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression in N. benthamiana has particularly accelerated functional characterization of plant biosynthetic enzymes. Compared to E. coli or yeast, this approach allows for rapid and simultaneous co-expression of multiple metabolic genes with significantly less effort in engineering and optimizing the cloning platform [28].

Isotopic Labeling Experiments

Feeding experiments with isotope-labeled precursors (e.g., ¹³C, ²H, ¹âµN) remain crucial for tracing the incorporation of primary metabolites into secondary metabolite scaffolds. The protocol involves:

- Preparing labeled precursors (e.g., L-aspartic acid, glycerol) in appropriate solvents

- Feeding to plant cell cultures or enzyme assays at relevant developmental stages

- Extracting metabolites after specific time intervals

- Analyzing incorporation patterns using LC-MS or NMR techniques

- Mapping labeled atoms to specific positions in the final natural product structure

In the discovery of ß-NAD-derived natural products, isotopic labeling experiments revealed significant label incorporation for L-aspartic acid and glycerol, providing crucial clues about the primary metabolic origins of the 6-azatetrahydroindane scaffold [8].

Gene Silencing Approaches

For confirming gene function in planta, several silencing approaches are employed:

- Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS): Using modified viruses to deliver gene fragments that trigger RNA silencing of endogenous genes

- RNA Interference (RNAi): Stable transformation with constructs producing dsRNA targeting specific genes

- CRISPR-Cas9: Creating knockout mutations in target genes to observe metabolic consequences

These approaches allow researchers to connect gene function with metabolite production in the native plant context, providing essential validation of proposed biosynthetic roles.

Case Studies: Successful Pathway Elucidation

The Discovery of ß-NAD as a Natural Product Building Block

A groundbreaking discovery in the field revealed that the pivotal primary metabolite ß-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (ß-NAD) can function as a building block for natural product biosynthesis, establishing a novel link between primary and secondary metabolism [8]. This case study exemplifies how innovative approaches can uncover entirely new biochemical paradigms.

Researchers investigating the biosynthesis of altemicidin, SB-203207, and SB-203208—compounds with a unique 6-azatetrahydroindane scaffold—employed a combination of genomic mining, heterologous expression, and untargeted metabolomics. The key breakthrough came when they constructed single gene expression strains in the heterologous host Streptomyces lividans TK21 and subjected culture extracts to metabolomic analysis, leading to identification of a highly polar metabolite that revealed an unexpected nucleotide metabolic origin [8].

The gatekeeping enzyme SbzP was found to catalyze an unprecedented PLP-mediated tandem Cα/Cγ-alkylation reaction, leading to cyclopentane annulation at the pyridinium moiety of ß-NAD through a (3+2)-cycloaddition reaction. This represents the first enzyme known to specifically tailor ß-NAD for natural product biosynthesis [8]. The following diagram illustrates this novel biochemical transformation.

Figure 2. Novel ß-NAD-Dependent Biosynthetic Pathway. This simplified pathway shows the unprecedented use of the primary metabolite ß-NAD as a building block for natural product biosynthesis.

Complete Pathway Elucidations of Plant Natural Products

Several complex plant natural product pathways have been completely elucidated through integrated omics approaches:

Vinblastine and vincristine: These anticancer monoterpene indole alkaloids from Catharanthus roseus involve approximately 30 enzymatic steps. Their elucidation combined genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic data, with co-expression analysis playing a crucial role in identifying missing pathway components [28].

Strychnine: The biosynthetic pathway of this complex alkaloid from Strychnos nux-vomica was reconstructed using chemical logic-informed prediction combined with omics data. Researchers used previously elucidated steps of geissochizine oxidation as starting points, predicting that the pathway includes decarboxylation, oxidation, and reduction steps [28].

Colchicine: The complete biosynthetic pathway for this antimitotic agent was assembled using co-expression analysis of transcriptomic data from Gloriosa superba, combined with heterologous reconstitution in Nicotiana benthamiana [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Modern natural product pathway discovery relies on a sophisticated array of research tools and reagents. The following table details key solutions essential for conducting this research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Natural Product Pathway Discovery

| Reagent/Solution Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Kits | DNA library prep kits, RNA-seq kits | Generation of genomic and transcriptomic libraries for high-throughput sequencing |

| Metabolomics Standards | Stable isotope-labeled internal standards, reference compounds | Quantification and identification of metabolites in complex mixtures |

| Cloning Systems | Gateway technology, Golden Gate assembly, T4 DNA ligase | Construction of expression vectors for candidate genes |

| Heterologous Host Systems | E. coli strains, S. cerevisiae strains, N. benthamiana plants | Functional expression and characterization of biosynthetic enzymes |

| Protein Purification Kits | Affinity chromatography resins, His-tag purification systems | Isolation of recombinant enzymes for biochemical characterization |

| Enzyme Assay Reagents | Cofactors (NADPH, PLP, SAM), substrate analogs | In vitro functional characterization of enzyme activities |

| Gene Silencing Reagents | VIGS vectors, RNAi constructs, CRISPR-Cas9 components | Functional validation of genes in planta through silencing |

| Analytical Standards | Authentic natural product standards, labeled precursors | Identification and quantification of pathway intermediates |

| N-(4-Carboxycyclohexylmethyl)maleimide | trans-4-(Maleimidomethyl)cyclohexanecarboxylic Acid | High-purity trans-4-(Maleimidomethyl)cyclohexanecarboxylic acid for research use only (RUO). A key intermediate for cross-linking reagents like SMCC. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Methioninol | L-Methioninol|CAS 2899-37-8|Research Chemical | L-Methioninol (C5H13NOS), 99+% purity. A key chiral building block for organic synthesis and biochemical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Future Directions and Emerging Technologies

The field of natural product discovery continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging technologies poised to further transform our approach to pathway elucidation.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

AI and ML are playing increasingly crucial roles in predicting gene functions, pathway components, and metabolic networks from complex omics datasets [4] [28]. Supervised machine learning approaches have already been successfully applied to pathway discovery for tropane alkaloids, monoterpene indole alkaloids, and benzylisoquinoline alkaloids [28]. The integration of AI tools is expected to accelerate the identification of novel biosynthetic pathways from the vast amount of available genomic and metabolomic data.

Single-Cell and Spatial Omics

Emerging techniques such as single-cell sequencing and MS imaging enable researchers to probe metabolic processes at unprecedented resolution, revealing the spatial organization of pathways within specific cell types [28] [29]. This is particularly important for plant natural products, which are often produced in highly specific cell types or organelles. Recent high-resolution analyses at the level of specific cell types, individual cells, or even organelles have revealed remarkable compartmentalization of plant metabolic pathways [28].

Sustainable Production through Metabolic Engineering

With complete biosynthetic pathways in hand, researchers are increasingly focusing on metabolic engineering strategies for sustainable production of valuable natural products. This includes engineering microbial hosts like yeast or bacteria to produce plant natural products, as demonstrated for artemisinic acid [29], as well as optimizing plant cell cultures for enhanced production of target compounds. Future directions include metabolon engineering, AI integration, and developing cheaper and greener production strategies for plant natural products [4].

The evolution of natural product discovery from simple plant extracts to comprehensive pathway elucidation represents a remarkable scientific journey that has transformed our understanding of plant chemical diversity. This transition has been enabled by the integration of multi-omics technologies, advanced computational tools, and innovative experimental approaches that collectively illuminate how plants transform simple primary metabolites into complex chemical scaffolds with significant pharmacological activities.

The ongoing integration of artificial intelligence, single-cell technologies, and sophisticated engineering approaches promises to further accelerate this field, potentially unlocking the full therapeutic potential of plant natural products while enabling sustainable production systems. As these advancements continue, our ability to decode and harness nature's chemical ingenuity will undoubtedly lead to new therapeutic agents and deeper insights into the fundamental biochemical principles that govern natural product biosynthesis.

Engineering Nature's Pathways: Methodologies for Harnessing and Applying Biosynthetic Logic

The field of metabolic engineering has undergone a significant transformation, entering a third wave characterized by the application of synthetic biology principles to design and construct complete metabolic pathways in microbial hosts for the production of noninherent chemicals [30]. This approach enables the systematic engineering of microbes such as E. coli and yeast to function as efficient cell factories, converting renewable biomass into valuable chemicals, fuels, and pharmaceuticals [31] [30]. Pathway reconstruction involves the careful selection of genetic parts, their assembly into functional pathways, and the optimization of metabolic flux to achieve high titers, yields, and productivity of target compounds [31]. This technical guide outlines the core principles and methodologies for successful heterologous pathway expression, framed within the context of producing biosynthetic building blocks from primary metabolism.

The synthetic biology approach to metabolic engineering typically follows an iterative workflow comprising four key stages: design, modeling, synthesis, and analysis [31]. This framework provides a standardized methodology for building biological systems from well-characterized, modular parts, moving beyond the traditional trial-and-error approach to a more predictable, engineering-based discipline [31]. The application of this framework is particularly valuable for rewiring cellular metabolism to enhance the production of target compounds, including medicinal plant bioactive compounds, where challenges such as long metabolic pathways, inadequate catalytic efficiency of key enzymes, and incompatibility between genetic elements and host cells often limit yields [32].

Core Principles and Design Framework

The Four-Stage Engineering Cycle

The forward engineering of synthetic metabolic pathways relies on a cyclical process that integrates computational design with experimental validation [31].

Design: This initial phase involves selecting appropriate genetic parts and formulating a blueprint for the metabolic pathway. The design process requires explicit specification of each necessary component, including promoters, ribosomal binding sites (RBSs), protein-coding sequences, and terminators [31]. At the pathway level, design focuses on mixing and matching modular parts while implementing control mechanisms to balance and optimize metabolic flux [31].

Modeling: Computational models are employed to predict system behavior before physical construction. Model-guided design approaches limit system variability by fitting mathematical models with measured parameters, increasing predictability and decreasing time spent on combinatorial system construction, testing, and debugging [31]. Genome-scale metabolic models are particularly valuable for exploring the metabolic potential of cell factories and identifying target genes for engineering [30].

Synthesis: This stage involves the physical construction of the designed genetic system using recombinant DNA technology. Advances in de novo DNA synthesis and codon optimization contribute significantly to manufacturing pathway enzymes with improved or novel function [31]. Standardized assembly methods, such as the BioBrick methodology, facilitate the construction process through well-defined genetic parts [31].

Analysis: The constructed pathways are experimentally validated through rigorous analysis of performance metrics. Analytical methods assess pathway functionality, metabolic flux, and product formation, generating data that inform subsequent design iterations [31]. This stage provides critical feedback for refining the system and improving its performance.

The following diagram illustrates this iterative engineering workflow:

Hierarchical Engineering Strategies

Modern metabolic engineering operates across multiple biological hierarchies to systematically rewire cellular metabolism [30]. This hierarchical approach enables precise intervention at different levels of cellular organization:

Part Level: Engineering focuses on individual genetic components, including promoters, RBSs, protein-coding sequences, and terminators. Libraries of standardized, characterized parts facilitate the predictable design of genetic circuits [31]. Key considerations at this level include codon optimization to match host preferences and the elimination of restriction sites for standardized assembly [31].

Pathway Level: Engineering involves the assembly of multiple genetic parts into functional metabolic pathways. At this level, balancing metabolic flux through tunable control mechanisms becomes critical [31]. Strategies include enzyme colocalization using protein scaffolds that bear modular interaction domains to physically link pathway enzymes [31].

Network Level: Engineering considers the interaction between the heterologous pathway and the host's native metabolic network. This may involve deleting competing pathways, overexpressing bottleneck enzymes, or modulating regulatory networks to redirect flux toward the desired product [30].

Genome Level: Engineering employs genome editing techniques to implement system-wide modifications. This includes creating knockout strains, integrating heterologous genes at specific genomic locations, and implementing genome-scale changes to optimize host performance [30].

Cell Level: Engineering addresses cellular properties beyond metabolism, including growth characteristics, stress tolerance, and product secretion. This may involve engineering transporter proteins to enhance substrate uptake or product efflux, or modifying cellular machinery to improve tolerance to toxic intermediates or products [30].

The relationship between these hierarchical levels is visualized in the following diagram:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Pathway Design and Codon Optimization

The successful reconstruction of heterologous pathways begins with careful in silico design and optimization of genetic components [31].

Codon Optimization: Protein-coding sequences must be optimized for expression in the heterologous host. Codon usage bias can significantly impact expression levels, and suboptimal codon usage may result in poor enzyme expression or misfolded proteins [31]. Utilize freely available algorithms such as Gene Designer or similar tools to encode the same amino acid sequence with alternative, preferred nucleotide sequences that match the host's codon preference [31].

Standardized Part Design: Genetic parts should comply with standard assembly requirements, such as the exclusion of specific restriction enzyme sites reserved for assembly in methodologies like BioBricks [31]. Additionally, part-specific objectives including activity or specificity modifications should be considered during the design phase [31].

Regulatory Element Selection: Choose appropriate promoters, RBSs, and terminators based on desired expression levels. Well-characterized part libraries, such as constitutive promoter libraries with varying strengths, enable fine-tuning of gene expression [31]. For inducible systems, select regulator-operator pairs that minimize cross-talk with host systems [31].

Assembly and Transformation

The physical construction of metabolic pathways involves the assembly of genetic parts and their introduction into the host chassis [31].

DNA Assembly: Utilize standardized assembly methods such as BioBricks, Golden Gate, or Gibson assembly to combine genetic parts into functional pathways. The choice of method depends on the number of parts, available resources, and compatibility with existing part libraries [31]. Ensure all parts are compatible with the selected assembly standard.

Host Transformation: Introduce the assembled genetic constructs into the microbial chassis using appropriate transformation methods. For E. coli, heat shock or electroporation are commonly used, while yeast typically requires lithium acetate or electroporation methods. Selectable markers are essential for identifying successful transformants.

Vector Selection: Choose appropriate vectors based on copy number, compatibility with the host, and stability. Origins of replication significantly impact plasmid copy number and should be selected based on desired expression levels [31]. For metabolic engineering applications, consider using low-copy vectors to reduce metabolic burden on the host.

Screening and Analysis

Following transformation, rigorous screening and analysis are required to identify successful pathway reconstruction and functionality [31].

Functional Screening: Implement high-throughput screening methods to identify clones with desired metabolic activity. This may include colorimetric assays, growth-based selection, or analytical techniques such as HPLC or GC-MS to detect product formation [33].

Pathway Analysis Tools: Utilize computational tools to analyze the performance of reconstructed pathways. Over-representation analysis and pathway topology analysis can help determine whether certain pathways are enriched in the engineered strains [34]. Tools such as Reactome provide statistical tests to identify over-represented pathways and visualize how submitted identifiers map to known pathways [34].

Flux Analysis: Employ metabolic flux analysis to quantify the flow of metabolites through pathways and identify potential bottlenecks. Techniques such as 13C-labeling can provide insights into intracellular flux distributions and guide further engineering efforts [30].

Case Studies and Performance Metrics

Representative Production Metrics in Engineered Hosts

The table below summarizes performance metrics for various chemicals produced through heterologous pathway expression in microbial chassis, demonstrating the effectiveness of hierarchical metabolic engineering strategies [30].

| Chemical | Host | Titer (g/L) | Yield (g/g) | Productivity (g/L/h) | Key Engineering Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Lactic Acid | C. glutamicum | 212 | 0.98 | - | Modular pathway engineering [30] |

| Succinic Acid | E. coli | 153.36 | - | 2.13 | Modular pathway engineering, High-throughput genome engineering, Codon optimization [30] |

| 3-Hydroxypropionic Acid | C. glutamicum | 62.6 | 0.51 | - | Substrate engineering, Genome editing engineering [30] |

| Lysine | C. glutamicum | 223.4 | 0.68 | - | Cofactor engineering, Transporter engineering, Promoter engineering [30] |

| Muconic Acid | C. glutamicum | 54 | 0.20 | 0.34 | Modular pathway engineering, Chassis engineering [30] |

| Malonic Acid | Y. lipolytica | 63.6 | - | 0.41 | Modular pathway engineering, Genome editing engineering, Substrate engineering [30] |

| Valine | E. coli | 59 | 0.39 | - | Transcription factor engineering, Cofactor engineering, Genome editing engineering [30] |

Advanced Engineering Applications

Beyond standard pathway reconstruction, several advanced applications demonstrate the cutting edge of heterologous expression technology:

Artemisinin Production: The complete metabolic pathway for artemisinic acid, a precursor to the antimalarial drug artemisinin, was reconstructed in yeast through extensive engineering of the mevalonate pathway and amorphadiene synthesis, followed by oxidation to artemisinic acid [30]. This landmark achievement demonstrated the potential for microbial production of complex plant-derived pharmaceuticals.

Enzyme Colocalization: Inspired by natural systems, protein scaffolds bearing modular interaction domains can physically link pathway enzymes tagged with corresponding peptide ligands [31]. This elegant approach enhances pathway efficiency by promoting substrate channeling and reducing intermediate diffusion.

RNA Devices: Synthetic RNA devices incorporating aptamers for sensing small molecules, transmitter sequences, and actuator elements such as ribozymes can provide sophisticated regulation of metabolic pathways [31]. These devices enable dynamic control of pathway expression in response to metabolic status.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful pathway reconstruction requires a comprehensive toolkit of genetic parts, analytical tools, and computational resources. The table below details essential research reagents and their applications in heterologous pathway engineering [31] [34] [33].

| Research Tool | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Biological Parts | Modular genetic elements for pathway construction [31] | Promoters, RBSs, coding sequences, terminators; Standardized for interoperability |

| Codon Optimization Software | Algorithmic optimization of coding sequences for heterologous hosts [31] | Adapts codon usage to host preferences; Tools: Gene Designer, DNA2.0 |

| Registry of Standard Biological Parts | Repository of characterized genetic parts [31] | Collection of standardized, reusable biological components |

| Pathway Analysis Tools | Computational identification of enriched pathways in engineered strains [34] [33] | Tools: g:Profiler, GSEA, Reactome; Statistical over-representation analysis |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Computational models predicting metabolic fluxes [30] | Identifies gene knockout/overexpression targets; Platforms: COBRA tools |

| RNA Devices | Post-transcriptional regulation of pathway expression [31] | Aptamer sensors, transmitter sequences, ribozyme actuators; Dynamic control |

| Protein Scaffolds | Physical colocalization of pathway enzymes [31] | Modular interaction domains with peptide ligands; Enhances metabolic channeling |

| L-Cysteine ethyl ester HCl | L-Cysteine Ethyl Ester Hydrochloride|RUO | Research-grade L-Cysteine ethyl ester hydrochloride for studying opioid side effects, antioxidant mechanisms, and more. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| O-tert-Butylthreoninetert-butyl ester | (2S,3R)-tert-Butyl 2-amino-3-(tert-butoxy)butanoate | Explore (2S,3R)-tert-Butyl 2-amino-3-(tert-butoxy)butanoate for life science research. This compound is a key building block in organic synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Pathway reconstruction for heterologous expression in microbial chassis represents a powerful paradigm for the sustainable production of valuable chemicals from renewable resources. The synthetic biology approach, with its emphasis on design, modeling, synthesis, and analysis, provides a rigorous framework for engineering microbial cell factories [31]. Hierarchical strategies that intervene at the part, pathway, network, genome, and cell levels enable comprehensive rewiring of cellular metabolism to optimize production metrics [30].

Future advancements in the field will likely focus on the development of more sophisticated regulatory tools, enhanced computational models for predicting pathway performance, and improved genome editing technologies for rapid strain optimization [32] [30]. The integration of machine learning approaches for designing optimal genetic constructs and predicting metabolic fluxes holds particular promise for accelerating the design-build-test cycle [30]. As these technologies mature, heterologous pathway expression in microbial chassis will play an increasingly important role in the sustainable production of chemicals, fuels, and pharmaceuticals, ultimately reducing resource consumption and environmental impact associated with traditional production methods [32].

Combinatorial biosynthesis is a powerful genetic engineering strategy that expands the biosynthetic inventory of native producers by introducing non-native enzymes into specific pathways, thereby manipulating natural product output to generate structurally diversified molecules [35]. This approach represents a fusion of genetic engineering and natural product chemistry, allowing researchers to extend nature's biosynthetic dexterity by reprogramming natural pathways through the mixing and matching of genes from known biosynthetic clusters [36]. The fundamental motivation driving the field is the production of "unnatural" natural products with altered structures that can illuminate structure-activity relationships crucial for drug development while improving the pharmaceutical properties of clinically relevant compounds [36].

This technical guide frames combinatorial biosynthesis within the broader context of primary metabolism research, wherein simple building blocks from central metabolic pathways—such as acyl-CoAs from fatty acid metabolism, amino acids from protein synthesis, and isopentenyl pyrophosphate from the mevalonate pathway—serve as the foundational substrates for engineered biosynthetic systems [35]. By harnessing and redirecting the flux of these primary metabolic building blocks through engineered pathways, researchers can create novel chemical entities that expand the accessible chemical space for drug discovery and development.

Foundational Principles and Building Blocks

Biosynthetic Origins of Natural Product Scaffolds

Natural products are classified according to their biosynthetic origin, with major classes including polyketides, non-ribosomal peptides, terpenes, and hybrid molecules that combine structural elements from multiple pathways [35]. From a biosynthetic perspective, the diversity and complexity of natural products are generated through a two-step process: (1) formation of the core hydrocarbon scaffold by megasynth(et)ases, and (2) modification of this scaffold by tailoring enzymes [35].

Fungal natural products, in particular, are produced via highly programmed pathways originating from simple building blocks derived from primary metabolism, including acyl-CoAs, proteinogenic and non-proteinogenic amino acids, isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP)/dimethylallylpyrophosphate (DMAPP), and sugars [35]. The engineered rerouting of these universal building blocks provides the foundation for combinatorial biosynthesis approaches.

Molecular Complexity Metrics for Pathway Evaluation

Recent advances in informatic methodology have enabled systematic comparison between biological and chemical synthetic strategies using molecular complexity metrics [37]. Key descriptors include:

- Molecular Weight (MW): Measured in Daltons (Da)

- Fraction of sp3 hybridized carbon atoms (Fsp3): Indicator of three-dimensionality

- Complexity Index (Cm): Quantitative measure of structural complexity

These metrics can be visualized in 3D plots parameterized by Fsp3, Cm, and MW to observe how complexity changes throughout a synthetic pathway, with efficient pathways creating complex specialized metabolites in as few processes as possible [37]. This analytical framework allows researchers to quantitatively compare the efficiency of combinatorial biosynthesis approaches against traditional chemical synthesis routes.

Key Engineering Strategies in Combinatorial Biosynthesis

Megasynth(et)ase Engineering

Megasynth(et)ases are large, multifunctional enzymes that synthesize the essential carbon framework of natural products. For polyketide synthases (PKSs), particularly non-reducing PKSs (NR-PKSs), several domain swapping strategies have been successfully employed:

Table: Domain Swapping Strategies in Non-Reducing PKS (NR-PKS) Engineering

| Domain Type | Function | Engineering Approach | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starter Unit Acyl Carrier Protein Transacylase (SAT) | Selects and transfers starter unit to ketosynthase domain [35] | Swapping between AfoE and StcA | Novel polyketide utilizing hexanoyl starter unit [35] |

| Product Template (PT) | Essential for cyclization and aromatization of polyketide chain [35] | Swap of PT from ApdA into PKS4 | Production of novel α-pyranoanthraquinone [35] |

| C-Methyltransferase (CMeT) | Catalyzes methylation of growing polyketide chain [35] | Combinatorial swaps between multiple NR-PKSs | Revealed kinetic competition with KS domain may override CMeT function [35] |

| Thiolesterase (TE) | Catalyzes polyketide cyclization and release [35] | Swapping between AtCURS1/2 and CcRADS1/2 | Generated multiple macrocycles, pyrones, carboxylic acids, and esters [35] |

For highly reducing PKS (HR-PKS), engineering challenges increase due to the frequent absence of terminal release domains and difficulties in detecting non-aromatic products [35]. Successful examples include enoylreductase (ER) domain swaps in DrtA, the HR-PKS involved in biosynthesis of fungal drimane-type sesquiterpene esters, which led to production of novel metabolites including calidoustrene F with different levels of saturation in the attached polyketide chain [35].

Building Block Pathway Engineering

Structural diversification by combinatorial biosynthesis can be limited by the substrate specificity of biosynthetic enzymes. Key engineering approaches include:

Expanding Polyketide Extender Unit Repertoire

The gatekeeper enzyme domain in modular PKSs is the acyltransferase (AT) domain that controls selection and incorporation of extender units (usually malonyl-, methylmalonyl-, or ethylmalonyl-CoAs) [36]. The restricted versatility of polyketide extender units has historically limited generation of novel polyketide structures, but this constraint has been addressed through:

- Discovery of crotonyl-CoA carboxylase/reductase (CCR) enzymes that catalyze reductive carboxylation of α,β-unsaturated acyl-CoA precursors [36]

- Engineering of AT domain specificity through amino acid substitutions to alter extender unit selectivity [36]

- Utilization of malonyl-CoA synthetase (MatB) with naturally or engineered promiscuous AT domains to incorporate diverse extender units [36]

For example, the AT domain of module 4 in the immunosuppressant FK506 PKS naturally accepts methylmalonyl-, ethylmalonyl-, propylmalonyl-, and allylmalonyl-CoA substrates as well as unnatural acyl-CoAs, generating macrolide derivatives with modified C21 side chains, one of which exhibited improved in vitro nerve regenerative activity relative to the parent FK506 [36].

Reprogramming Non-Ribosomal Peptide Assembly

In non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) systems, adenylation (A) domains control the entry of diverse amino acid substrates to the NRPS assembly line. Engineering strategies include:

- Rational design through point mutations in specificity-determining residues

- Directed evolution of A domains through saturation mutagenesis of specificity-conferring sites

- Exploitation of natural substrate promiscuity in selected A domains

A notable example includes the modification of the A domain of module 10 within the calcium-dependent antibiotic (CDA) NRPS through a single mutation (Lys278Gln), changing its specificity from (2S,3R)-3-methyl Glu (mGlu)/Glu to (2S,3R)-3-methyl Gln (mGln)/Gln to produce novel CDA analogues [36].

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Heterologous Pathway Expression Systems

The implementation of combinatorial biosynthesis strategies typically requires reconstruction of engineered pathways in suitable heterologous hosts. Well-established experimental workflows include:

4.1.1 Fungal Host Engineering in Aspergillus oryzae

- Protocol: The biosynthetic pathway for sporothriolide was fully reconstructed in Aspergillus oryzae, requiring expression of genes encoding two fungal fatty acid synthase components (SpofasA & B), an alkyl citrate synthase (SpoE), a methylcitrate dehydratase homolog (SpoL), a decarboxylase (SpoK), a non-heme iron dioxygenase (SpoG), and hydrolases SpoH and SpoJ [37].

- Key Considerations: Use of strong inducible promoters, codon optimization for heterologous expression, and balanced expression of large multimodular proteins.

4.1.2 Bacterial Host Engineering in Escherichia coli

- Protocol: Engineering of E. coli for production of novel polyketides through expression of heterologous PKS genes, including those requiring specific cofactors or post-translational modifications.

- Key Considerations: Implementation of phosphopantetheinyl transferases for ACP activation, co-expression of precursor supply pathways, and optimization of fermentation conditions.

DNA Assembly and Pathway Refactoring

Modern combinatorial biosynthesis relies on advanced DNA assembly techniques for pathway construction:

- Golden Gate Assembly: For modular assembly of large biosynthetic gene clusters

- Yeast Assembly: For reconstruction of very large gene clusters (>50 kb)

- CRISPR-Cas Mediated Genome Editing: For precise genome integration of engineered pathways

- Modular Cloning Systems: Such as MoClo or GoldenBraid for standardized parts assembly

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Combinatorial Biosynthesis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus oryzae heterologous expression system | Robust fungal host for expression of fungal biosynthetic pathways [37] | Reconstruction of sporothriolide biosynthetic pathway [37] |