FBA vs Kinetic Modeling: A Comprehensive Guide to Metabolic Network Analysis for Drug Discovery

This article provides a detailed comparison of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and kinetic modeling, two foundational approaches in systems biology for studying metabolic networks.

FBA vs Kinetic Modeling: A Comprehensive Guide to Metabolic Network Analysis for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and kinetic modeling, two foundational approaches in systems biology for studying metabolic networks. Targeted at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the core principles, practical applications, common challenges, and validation strategies for each method. We synthesize current best practices to guide the selection and implementation of these powerful computational tools for predicting metabolic phenotypes, identifying drug targets, and accelerating biomarker discovery in pharmaceutical research.

Understanding the Basics: Core Principles of FBA and Kinetic Modeling

Within the ongoing research discourse on metabolic modeling, a fundamental dichotomy exists between constraint-based and kinetic approaches. This whitepaper elucidates Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), the cornerstone of the constraint-based paradigm, contrasting it with kinetic modeling. Kinetic models require extensive parameterization (e.g., enzyme kinetic constants) which are often unavailable, limiting their scope to small, well-characterized pathways. In contrast, FBA operates under a steady-state assumption, circumventing the need for kinetic parameters by leveraging genome-scale metabolic reconstructions to predict systemic flux distributions. This positions FBA as a powerful, scalable tool for analyzing large-scale metabolic networks in biotechnology and medicine, albeit with different predictive capabilities and data requirements than kinetic models.

Core Principles and Mathematical Formulation

FBA is grounded in the physicochemical constraints that govern metabolic networks. The core formulation is as follows:

Objective: Maximize/Minimize ( Z = c^T v ) (a linear objective function, e.g., biomass production). Subject to: ( S \cdot v = 0 ) (Mass balance constraint: steady-state). ( \alphai \leq vi \leq \beta_i ) (Capacity constraints: enzyme kinetics and thermodynamics).

Where:

- ( S ) is the ( m \times n ) stoichiometric matrix.

- ( v ) is the ( n )-dimensional flux vector.

- ( c ) is a weight vector defining the biological objective.

- ( \alphai ) and ( \betai ) are lower and upper bounds for flux ( v_i ).

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of FBA vs. Kinetic Modeling

| Feature | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Kinetic Modeling (for contrast) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Data | Stoichiometry, Network topology, Flux constraints | Enzyme mechanisms, Kinetic constants (Km, Vmax) |

| System State | Steady-state | Dynamic (time-course) |

| Mathematical Form | Linear Programming (LP) | Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) |

| Network Scale | Genome-scale (1000s of reactions) | Small-scale pathways (10s of reactions) |

| Parameter Demand | Low (primarily flux bounds) | High (detailed kinetic parameters) |

| Primary Output | Flux distribution at steady-state | Metabolite concentrations over time |

| Key Strength | Scalability, Hypothesis generation | Detailed mechanistic insight, Dynamic prediction |

Key Experimental Protocols for FBA Validation and Application

Protocol 1: Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstruction

- Draft Reconstruction: Automatically generate a reaction list from annotated genomes (e.g., using ModelSEED, KBase).

- Manual Curation: Refine reaction list, fill knowledge gaps, and correct dead-end metabolites using literature and databases (e.g., MetaCyc, KEGG).

- Compartmentalization: Assign metabolites and reactions to cellular compartments.

- Biomass Objective Function (BOF) Definition: Formulate a pseudo-reaction representing the drain of precursors for biomass synthesis, based on experimental composition data.

- Network Validation: Test model for mass and charge balance, and ability to produce known biomass components under defined media.

- Model Constraint Setting: Set the upper bound for the exchange reaction of the target carbon source (e.g., glucose) to a non-zero value (e.g., 10 mmol/gDW/h). Set oxygen and other essential nutrient exchange reactions accordingly.

- Objective Definition: Set the biomass reaction as the objective function to maximize.

- Linear Programming: Solve the LP problem using a solver (e.g., COBRApy, COBRA Toolbox).

- Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): Perform FVA to determine the feasible range for each reaction flux while maintaining optimal growth.

- Experimental Correlation: Compare predicted growth rates (from the objective value) and essential genes (via in silico gene knockout) with wet-lab chemostat or batch culture data.

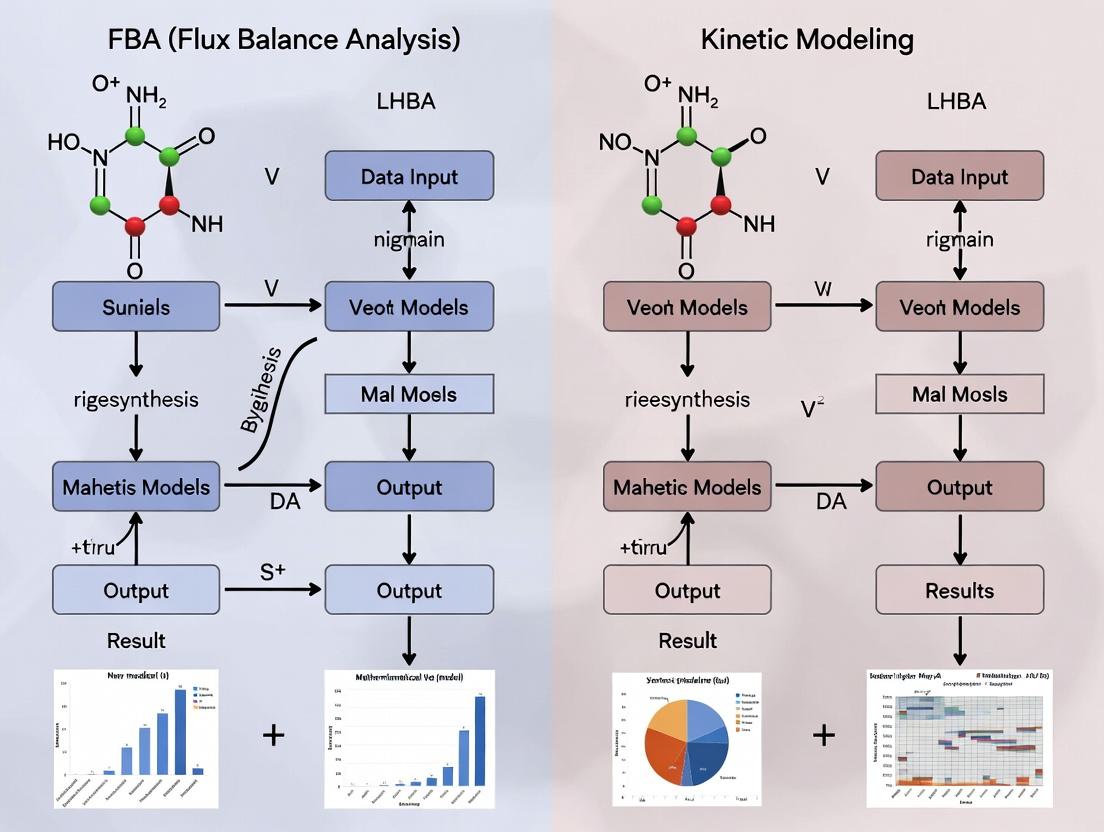

Visualization of Core Concepts

FBA Core Workflow

FBA vs Kinetic: Decision Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for FBA Studies

| Item | Function in FBA Research |

|---|---|

| Genome Annotation Database (e.g., UniProt, KEGG, BioCyc) | Provides the foundational gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations to draft metabolic reconstructions. |

| Curated Metabolic Database (e.g., MetaCyc, BiGG Models, RAVEN Toolbox) | Offers manually curated biochemical reaction data for network refinement and gap-filling. |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Software (e.g., COBRA Toolbox, COBRApy, RAVEN) | Software suites implementing LP solvers (e.g., GLPK, CPLEX, Gurobi) and algorithms for FBA, FVA, and gene knockout. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (e.g., ¹³C-Glucose, ¹⁵N-Ammonia) | Used in Fluxomics experiments to validate in silico FBA predictions by measuring intracellular flux distributions via MFA. |

| Defined Growth Media Kits | Essential for in vitro experiments to correlate model predictions (on specific carbon/nitrogen sources) with measured cellular growth phenotypes. |

| Gene Knockout/KD Collections (e.g., Keio Collection for E. coli) | Enables experimental validation of model-predicted essential genes and synthetic lethality. |

| High-Throughput Phenotype Microarrays (e.g., Biolog Phenotype MicroArrays) | Allows parallel testing of growth on hundreds of carbon sources, providing rich data for model validation and refinement. |

Within the ongoing research discourse comparing constraint-based (e.g., Flux Balance Analysis, FBA) and kinetic modeling approaches, kinetic modeling emerges as the dynamic, mechanism-driven framework. FBA provides a powerful, steady-state snapshot of metabolic potential but lacks temporal resolution and explicit regulatory detail. In contrast, kinetic modeling explicitly describes the time-dependent behavior of biochemical systems using enzyme mechanisms, reaction rates, and metabolite concentrations, enabling the prediction of dynamic responses to perturbations—a critical capability in drug development and systems biology.

Core Principles of Kinetic Modeling

Kinetic models are constructed from mechanistic descriptions of biochemical reactions, typically represented by ordinary differential equations (ODEs). The core equation for a metabolite concentration ( C_i ) is:

[ \frac{dCi}{dt} = \sum{j} S{ij} vj ]

where ( S{ij} ) is the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite *i* in reaction *j*, and ( vj ) is the rate law for reaction j. The rate law (e.g., Michaelis-Menten, Hill, or more complex modular rate laws) encodes the enzyme mechanism and regulatory interactions.

Quantitative Data Comparison: FBA vs. Kinetic Modeling

Table 1: Key Characteristics of FBA vs. Kinetic Modeling

| Feature | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Optimization of an objective function (e.g., biomass) at steady-state. | Integration of ODEs derived from mechanistic rate laws. |

| Temporal Resolution | None (steady-state only). | Explicit (predicts dynamics over time). |

| Required Data | Genome-scale stoichiometric matrix; exchange constraints. | Enzyme kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax, kcat, KI), initial concentrations. |

| Parameter Demand | Low (only flux constraints). | Very High (parameters per reaction). |

| Regulatory Detail | Can be incorporated indirectly via constraints. | Explicitly encoded in rate equations (allosteric, inhibition). |

| Primary Output | Flux distribution (mmol/gDW/h). | Metabolite & enzyme concentration time courses. |

| Scalability | High (genome-scale models common). | Moderate to Low (large models suffer from parameter identifiability). |

| Key Application | Predicting growth phenotypes, knockout analysis. | Predicting transient responses, drug dosing effects, metabolic control. |

Table 2: Representative Kinetic Parameters for a Core Metabolic Pathway (Glycolysis)

| Enzyme | Rate Law Form | Typical Km (mM) | Typical kcat (1/s) | Reference / Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexokinase | Michaelis-Menten with ATP & product inhibition. | Glc: 0.05, ATP: 0.5 | 60 - 100 | Biochemical data repositories (BRENDA, SABIO-RK) |

| Phosphofructokinase | Complex (allosteric by ATP, AMP). | F6P: ~0.5 | 40 - 80 | Teusink et al., Eur J Biochem, 2000 |

| Pyruvate Kinase | Michaelis-Menten with ADP activation. | PEP: ~0.5, ADP: 0.3 | 50 - 200 | Marín-Hernández et al., FEBS J, 2009 |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Parameter Determination for Kinetic Modeling

Protocol Title: Determination of Enzyme Kinetic Parameters (Vmax, Km) via Coupled Spectrophotometric Assay

Objective: To obtain the maximal reaction rate (Vmax) and Michaelis constant (Km) for a purified enzyme, essential for constructing a kinetic model.

Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

Table 3: Scientist's Toolkit – Key Reagents for Enzyme Kinetics

| Item | Function & Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Purified Recombinant Enzyme | The catalyst of interest, produced in a heterologous system (e.g., E. coli) to ensure purity and sufficient quantity. |

| Spectrophotometer with Temperature Control | Measures the change in absorbance of NADH/NADPH at 340 nm over time, proportional to reaction rate. Must maintain constant assay temperature (e.g., 37°C). |

| 96-Well or Cuvette Assay Plates | Reaction vessels compatible with the spectrophotometer. |

| Enzyme-Specific Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) upon which the enzyme acts. A range of concentrations is prepared for Km determination. |

| Cofactors (e.g., NAD+/NADP+, ATP, Mg2+) | Essential cosubstrates or activators for the reaction. Mg2+ is often required for kinase/ATPase activity. |

| Coupled Enzyme System | A secondary enzyme system (e.g., pyruvate kinase/lactate dehydrogenase) that links the primary reaction to the consumption/production of NADH, allowing for continuous monitoring. |

| Assay Buffer | Maintains optimal pH and ionic strength (e.g., Tris-HCl or HEPES buffer at pH 7.4). |

| Data Fitting Software (e.g., Prism, KinTek Explorer) | Used to fit the initial velocity data to the Michaelis-Menten or other appropriate equation to extract Vmax and Km. |

Methodology:

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: For each substrate concentration, prepare a master mix containing constant concentrations of assay buffer, cofactors, coupling enzymes, and the indicator (NAD+/NADH). Omit the primary enzyme.

- Initial Rate Measurement: Aliquot the master mix into wells/cuvettes. Pre-incubate at 37°C. Initiate the reaction by adding a known volume of purified enzyme. Immediately monitor the change in absorbance at 340 nm for 1-5 minutes.

- Data Collection: Record the slope of the linear portion of the absorbance vs. time curve. This slope ((\Delta)Abs/min) is converted to reaction velocity (v, e.g., µM/min) using the extinction coefficient for NADH (6220 M⁻¹cm⁻¹).

- Parameter Estimation: Plot initial velocity (v) against substrate concentration ([S]). Fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation: ( v = \frac{V{max} [S]}{Km + [S]} ) using non-linear regression software to obtain Vmax and Km estimates.

Signaling Pathway & Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: From Signaling Mechanism to Kinetic Model (94 chars)

Diagram 2: Kinetic Model Development & Iteration Workflow (99 chars)

This article examines the foundational philosophical divide between optimization-driven and mechanistic-descriptive modeling paradigms within the context of constraint-based Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and kinetic modeling approaches in systems biology and drug development.

Foundational Philosophical Frameworks

The core distinction lies in the underlying epistemology and objective of each approach.

- Optimization (FBA Paradigm): Operates on the principle of teleology—understanding a system by its purpose or goal. It assumes biological networks, particularly metabolic networks, are optimized by evolution for specific objectives (e.g., maximization of biomass, ATP production). It is fundamentally top-down and constraint-based, using stoichiometry and boundary conditions to define a "solution space" of possible states, from which an optimal state is selected.

- Mechanistic Description (Kinetic Modeling Paradigm): Adheres to the principle of causality—understanding a system by describing the precise cause-and-effect interactions of its components. It seeks to describe the dynamic mechanisms governing system behavior over time, relying on detailed biochemical parameters (e.g., enzyme concentrations, kinetic rates, affinities). It is bottom-up and deterministic/stochastic.

Comparative Analysis: FBA vs. Kinetic Modeling

The table below summarizes the quantitative and qualitative differences stemming from their philosophical roots.

Table 1: Core Comparison of FBA (Optimization) and Kinetic Modeling (Mechanistic)

| Feature | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Teleological Optimization | Mechanistic Causality |

| Primary Objective | Predict an optimal flux distribution for a given biological objective. | Describe time-course dynamics of molecular species. |

| Mathematical Basis | Linear Programming / Constraint-based optimization. | Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) / Stochastic simulations. |

| Key Inputs | Stoichiometric matrix (S), exchange flux bounds, objective function (e.g., max biomass). | Enzyme kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax), initial metabolite concentrations, rate laws. |

| Data Requirements | Relatively low: Genome-scale reconstruction, some uptake/secretion rates. | Very high: Extensive kinetic constants and concentration data. |

| Scalability | High: Easily models genome-scale networks (1000s of reactions). | Low: Typically limited to small, well-characterized pathways (<100 reactions). |

| Temporal Resolution | Steady-state only (no time dynamics). | Explicit time dynamics (transient and steady states). |

| Output | A single flux distribution or set of possible fluxes. | Concentrations and fluxes as functions of time. |

| Major Strength | Genome-scale predictions, robust to missing parameters, ideal for metabolic engineering. | Detailed mechanistic insight, captures regulation and dynamics, suitable for drug target analysis. |

| Major Limitation | Lacks molecular detail and dynamics; reliant on assumed objective function. | Parameter uncertainty and scarcity; difficult to scale. |

Table 2: Representative Quantitative Outputs from Recent Studies (2023-2024)

| Model Type | Study Focus | Key Quantitative Result | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| FBA (Optimization) | Predicting anticancer drug targets in cancer metabolism. | Identified 3 essential gene knockouts that reduced in silico cancer cell growth yield by >95% in 5 distinct cancer types. | Nature Communications, 2023 |

| Kinetic (Mechanistic) | Modeling RAS/ERK signaling pathway dynamics. | Precise IC50 shift of 2.7-fold for a MEK inhibitor was predicted and validated when feedback loops were included. | Cell Systems, 2024 |

| Hybrid | Integrated FBA & Kinetic model of central metabolism. | Improved prediction of metabolic shifts under diauxic growth, reducing error in acetate secretion prediction from 35% to 8%. | PNAS, 2023 |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol 1: Validating FBA-Growth Predictions (Chemostat Cultivation)

- Strain & Medium: Use a defined microbial strain (e.g., E. coli K-12) and minimal medium with a single carbon source (e.g., glucose).

- Cultivation: Perform continuous cultivation in a bioreactor under chemostat conditions at a fixed dilution rate (D).

- Steady-State Measurement: Achieve and confirm steady state by monitoring OD600 and substrate/product concentrations for ≥5 residence times.

- Quantification: Measure uptake (glucose, O2) and secretion (CO2, acetate) rates via HPLC and off-gas analysis.

- Model Comparison: Construct a species-specific genome-scale model (GEM). Set the measured uptake rates as constraints. Run FBA with the objective of maximizing biomass formation. Compare the in silico predicted growth rate and secretion fluxes to the experimentally measured ones.

Protocol 2: Validating Kinetic Model of Enzyme Inhibition (In Vitro Assay)

- Recombinant Enzyme: Purify the target enzyme (e.g., human DHFR).

- Assay Conditions: Establish a continuous spectrophotometric activity assay in a multi-well plate reader.

- Substrate Kinetics: Vary the primary substrate concentration across a range (e.g., 0.1-10 x Km) at a fixed, saturating concentration of co-factors. Fit data to the Michaelis-Menten equation to determine Km and Vmax.

- Inhibitor Titration: Repeat activity measurements at a fixed substrate concentration (near Km) while titrating the inhibitor concentration.

- Model Fitting: Integrate the rate law (e.g., competitive inhibition) into an ODE model. Use software (COPASI, MATLAB) to fit the kinetic parameters (Ki) to the experimental time-course data of product formation.

Visualizing the Paradigms and Workflows

Workflow: FBA vs Kinetic Modeling Paradigms

RAS/ERK Pathway with Drug Inhibition & Feedback

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Model Development and Validation

| Item | Function | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | A structured, computational knowledge base of an organism's metabolism for FBA. Required as the starting constraint matrix. | BiGG Models Database (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli); MetaCyc. |

| Constraint-Based Reconstruction & Analysis (COBRA) Toolbox | Standard MATLAB/SciPy suite for building, simulating, and analyzing constraint-based models. | COBRApy (Python), The COBRA Toolbox for MATLAB. |

| Kinetic Parameter Database | Curated repository of enzyme kinetic constants (Km, kcat) for populating mechanistic models. | BRENDA, SABIO-RK, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). |

| ODE/Stochastic Simulation Software | Platform for constructing, simulating, and fitting kinetic models. | COPASI (free), MATLAB SimBiology, libRoadRunner. |

| Defined Minimal Media | For reproducible cultivation experiments to generate validation data for metabolic models. | M9 Minimal Salts (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich M6030), custom formulations. |

| Recombinant Purified Enzyme | Highly purified target enzyme for in vitro kinetic characterization and inhibitor assays. | Commercial vendors (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich, R&D Systems) or in-house expression/purification. |

| Fluorogenic/Coupled Enzyme Assay Substrate | Enables continuous, high-throughput measurement of enzyme activity for kinetic parameter estimation. | Example: 7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin (4-MU) based fluorogenic substrates for hydrolases. |

| Microplate Reader with Kinetic Capability | Instrument for performing high-throughput, time-course measurements of absorbance/fluorescence in enzyme or cell-based assays. | Devices from BioTek, Molecular Devices, or BMG Labtech. |

Within the ongoing research discourse comparing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and kinetic modeling for metabolic network analysis, the selection of an appropriate approach is fundamentally dictated by available data. This guide delineates the specific data prerequisites for each methodology, underscoring how these requirements shape their applicability in drug development and systems biology.

Data Requirements for Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

FBA is a constraint-based modeling approach that predicts steady-state metabolic fluxes. Its data needs are primarily stoichiometric and thermodynamic.

Core Data Prerequisites

1.1.1 Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstruction (GEM)

- Description: A structured, biochemical knowledgebase representing all known metabolic reactions and genes for an organism.

- Source: Manually curated from literature and databases (e.g., BiGG, ModelSEED). Automated drafts can be generated from annotated genomes.

- Format: Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) is standard.

1.1.2 Stoichiometric Matrix (S)

- Description: A mathematical matrix derived from the GEM where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions. Elements are stoichiometric coefficients.

- Requirement: Must be a prerequisite. Defines the network structure for the flux solution space.

1.1.3 Objective Function

- Description: A linear combination of fluxes (e.g., biomass reaction, ATP production) to be maximized or minimized.

- Requirement: Must be defined. Often a biomass objective function for cellular growth.

1.1.4 Constraints

- Description: Quantitative bounds applied to reaction fluxes (v), defining the feasible solution space: α ≤ v ≤ β.

- Types:

- Irreversibility Constraints: Set α=0 for thermodynamically irreversible reactions.

- Capacity Constraints: Set β based on enzyme Vmax data (if available).

- Measured Flux Constraints: Incorporate data from (^{13}\text{C}) Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) to narrow solution space.

Experimental Protocol: (^{13}\text{C}) Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) for FBA Validation

A key experiment to generate constraining data for FBA.

- Culture: Grow cells in a controlled bioreactor with a defined (^{13}\text{C})-labeled substrate (e.g., [1-(^{13}\text{C})]glucose).

- Steady-State Harvest: Ensure culture is at metabolic steady-state (constant metabolites and growth). Harvest cells rapidly (quenching).

- Metabolite Extraction: Use cold methanol/water or other extraction protocols for intracellular metabolites.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS) Analysis: Analyze proteinogenic amino acids or central metabolic intermediates via GC-MS or LC-MS to determine (^{13}\text{C}) labeling patterns (isotopomer distributions).

- Computational Flux Estimation: Use software (e.g., INCA, OpenFlux) to fit a network model to the measured labeling data, estimating intracellular metabolic fluxes.

- Integration with FBA: Use the estimated fluxes as additional equality constraints (v = v_MFA) in the FBA problem to refine predictions.

Table 1: Core Data Requirements for FBA

| Data Type | Description | Typical Source | Criticality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix | Network structure (S-matrix) | Genome-scale reconstruction | Absolute Mandatory |

| Objective Function | Linear objective (e.g., Z = c^T v) | Literature, assumption | Mandatory |

| Irreversibility Constraints | Thermodynamic directionality (α) | Literature, databases | Mandatory |

| Capacity Constraints (β) | Enzyme kinetic data (Vmax) | Experiments, literature | Optional (Refines) |

| Measured Flux Data | e.g., from (^{13}\text{C})-MFA | Experiments | Optional (Refines/Validates) |

| Omics Data (Transcript/Protein) | Expression levels | Microarrays, RNA-seq, Proteomics | Optional (Creates context-specific models) |

Data Requirements for Kinetic Modeling

Kinetic modeling aims to predict dynamic metabolic behaviors by explicitly incorporating enzyme kinetics. Its data requirements are far more extensive and quantitative.

Core Data Prerequisites

2.1.1 Metabolic Network Structure

- Description: A defined set of metabolic reactions, similar to but often smaller in scale than an FBA network due to data limitations.

2.1.2 Enzyme Kinetic Parameters

- For each reaction, parameters for a chosen rate law (e.g., Michaelis-Menten) are required:

- Vmax: Maximum enzyme velocity. Often derived from in vitro assays.

- Km: Michaelis constant(s) for each substrate.

- K_i: Inhibition constants for known allosteric inhibitors.

- Challenge: Severe scarcity of consistent, in vivo-relevant parameter sets.

2.1.3 Dynamic Concentration Data

- Description: Time-series measurements of metabolite concentrations under perturbation (e.g., substrate pulse, inhibitor addition).

- Purpose: Essential for model calibration (parameter estimation) and validation.

- Method: Typically obtained via LC-MS/MS or NMR.

2.1.4 Initial Conditions

- Description: The concentrations of all model metabolites at the simulation start time (t=0).

- Requirement: Must be defined, often from the same dynamic experiments.

Experimental Protocol: Parameter Estimation & Model Calibration

A critical iterative process for building kinetic models.

- Network Definition: Define the boundary of the subnetwork to be modeled.

- Rate Law Assignment: Assign an appropriate mechanistic or approximate rate law (e.g., convenience kinetics) to each reaction.

- Prior Parameter Data Collection: Gather known kinetic parameters from literature and databases (e.g., BRENDA).

- Perturbation Experiment: Subject cells to a defined metabolic perturbation (e.g., glucose shift, drug dose). Rapid sampling at multiple time points (seconds to minutes).

- Metabolomics: Quantify absolute concentrations of network metabolites at each time point using targeted MS.

- Computational Fitting: Use software (e.g., COPASI, PySB) to fit unknown model parameters by minimizing the difference between simulated and experimental concentration time-courses. Techniques include global optimization (e.g., genetic algorithms).

Table 2: Core Data Requirements for Kinetic Modeling

| Data Type | Description | Typical Source | Criticality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Stoichiometry | Reaction list & balances | Literature, databases | Absolute Mandatory |

| Kinetic Parameters (Vmax, Km, Ki) | Enzyme mechanism constants | In vitro assays, literature, estimation | Mandatory |

| Dynamic Metabolite Concentrations | Time-series data post-perturbation | LC-MS/MS, NMR experiments | Mandatory for Calibration |

| Initial Metabolite Concentrations | Concentrations at t=0 | Same as dynamic experiments | Mandatory |

| Enzyme Concentration/Activity | Total active enzyme levels | Proteomics, activity assays | Highly Recommended |

Table 3: Comparative Summary of Data Requirements

| Aspect | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data | Stoichiometry, Constraints (Bounds) | Enzyme Kinetics, Dynamic Concentrations |

| Network Scale | Genome-scale (100s-1000s reactions) | Small to medium-scale (10s-100s reactions) |

| Temporal Resolution | Steady-state (time-invariant) | Dynamic (time-series) |

| Quantitative Demand | Moderate (growth/uptake rates, some fluxes) | Very High (parameters & concentrations) |

| Parameter Needs | Few (constraint bounds) | Extensive (kinetic constants per reaction) |

| Key Validation Experiment | (^{13}\text{C})-MFA for flux distributions | Time-resolved metabolomics after perturbation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Featured Experiments

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| (^{13}\text{C})-Labeled Substrates | Tracers for (^{13}\text{C})-MFA to determine intracellular flux maps. |

| Quenching Solution (Cold Methanol/Water) | Rapidly halts metabolism to capture in vivo metabolite levels. |

| Internal Standards (Stable Isotope-Labeled Metabolites) | For absolute quantification in LC-MS/MS metabolomics. |

| Recombinant Enzymes | For in vitro assays to determine kinetic parameters (Vmax, Km). |

| Inhibitors/Activators | To perturb metabolic pathways for dynamic model calibration. |

| SBML-Compatible Software (COBRApy, COPASI) | For constructing, simulating, and analyzing FBA/kinetic models. |

| Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS, LC-MS/MS) | Core instrument for measuring isotope labeling and metabolite concentrations. |

Visualizations

Title: FBA Model Construction and Data Integration Workflow

Title: Kinetic Model Building and Calibration Process

Title: Decision Logic for Selecting FBA vs. Kinetic Modeling

Historical Context and Evolution in Systems Biology

This whitepaper examines the historical trajectory of systems biology, focusing on the development and philosophical divide between two dominant modeling paradigms: constraint-based methods, exemplified by Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), and kinetic modeling approaches. This evolution is framed within a broader thesis that argues for a synergistic, context-dependent application of both approaches rather than viewing them as mutually exclusive competitors. The choice between FBA and kinetic modeling is fundamentally governed by the biological question, available data quality, and desired predictive granularity.

Historical Timeline and Conceptual Evolution

Systems biology emerged from the convergence of high-throughput “omics” technologies, computational power, and theoretical frameworks from cybernetics and quantitative biochemistry.

- Pre-1990s (Foundations): Early work on metabolic control analysis (MCA) and biochemical systems theory laid the mathematical groundwork. The focus was on small, well-characterized pathways.

- 1990s (Genomics & Reconstruction): The completion of genome projects enabled the first genome-scale metabolic network reconstructions (e.g., Haemophilus influenzae). FBA, leveraging linear programming and the principle of optimality (e.g., maximal growth yield), became a powerful tool for analyzing these large networks.

- 2000s (Omics Integration & Multiscale Modeling): The proliferation of transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data drove the need for more dynamic models. Kinetic modeling advanced but was hampered by parameter identifiability issues. The field recognized the complementarity: FBA for steady-state flux predictions and kinetic models for dynamics and regulation.

- 2010s-Present (Mechanistic Integration & Whole-Cell Aims): Current research focuses on hybrid multi-scale models, integrating FBA-derived constraints into detailed kinetic submodules. Efforts like the whole-cell modeling of Mycoplasma genitalium exemplify the ambition to unify approaches. Machine learning is now used to infer kinetic parameters and guide model selection.

Core Methodologies: FBA vs. Kinetic Modeling

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

- Principle: Applies mass-balance, steady-state, and capacity constraints to a stoichiometric network to calculate a feasible flux distribution, often optimizing for a biological objective.

- Protocol Outline:

- Network Reconstruction: Build a stoichiometric matrix S from genome annotation and biochemical literature.

- Define Constraints: Apply mass balance: S·v = 0. Set lower/upper bounds (lb, ub) for each reaction flux (v).

- Define Objective Function: Typically biomass maximization: maximize Z = cᵀ·v.

- Solve Linear Program: Use a solver (e.g., COBRA, GLPK) to find optimal flux distribution.

- Strengths: Scalable to genome-size; requires no kinetic parameters; predicts optimal phenotypes.

- Weaknesses: Assumes steady-state; lacks dynamic and regulatory information.

Kinetic Modeling

- Principle: Uses ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to describe the time-dependent concentration changes of metabolites based on enzymatic rate laws.

- Protocol Outline:

- Define Reaction Network: List all reactions and enzymatic mechanisms.

- Formulate ODEs: For each metabolite, dX/dt = Σ (production fluxes) - Σ (consumption fluxes).

- Parameterization: Obtain kinetic constants (Km, Vmax) from literature, experiments, or fitting to time-series data.

- Simulation & Validation: Numerically integrate ODEs (e.g., using COPASI, MATLAB) and compare predictions to experimental data.

- Strengths: Captures dynamics, regulation, and metabolite concentrations; more mechanistic.

- Weaknesses: Parameter scarcity/uncertainty; poor scalability to large networks.

Quantitative Comparison of Paradigms

Table 1: Comparison of FBA and Kinetic Modeling Approaches

| Feature | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Basis | Linear Programming / Constraint Optimization | Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) |

| Core Data Requirement | Stoichiometry, Reaction Directions, Growth Media | Kinetic Parameters (Km, Kcat), Initial Concentrations |

| Temporal Resolution | Steady-State (No time component) | Dynamic (Explicit time course) |

| Network Scale | Genome-Scale (1000s of reactions) | Small to Medium Pathways (10s-100s of reactions) |

| Regulatory Insight | Indirect (via constraints) | Direct (via kinetic terms & modifiers) |

| Parameter Burden | Low (Only flux bounds) | High (All kinetic constants) |

| Typical Output | Flux Distribution | Metabolite Concentration Time-Series |

| Primary Application | Metabolic Engineering, Growth Phenotype Prediction | Drug Target Discovery, Signaling Dynamics |

Table 2: Example Simulation Results for a Toy Glycolysis Pathway

| Modeling Approach | Predicted Glucose Uptake Flux | Predicted ATP Production Rate | Time to Steady-State | Key Parameter(s) Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBA (Biomass Max) | 10.0 mmol/gDW/hr | 25.0 mmol/gDW/hr | Not Applicable | Reaction Bounds, Objective |

| Michaelis-Menten Kinetic Model | 9.8 ± 0.5 mmol/L/s | 24.5 ± 1.2 mmol/L/s | ~2.5 seconds | VmaxHK=15, KmGlc=0.1 |

Experimental Protocol: Integrating FBA and Kinetic Models

Protocol: Creating a Hybrid Dynamic FBA (dFBA) Model Objective: To model the dynamic shift in metabolism during a batch culture transition from glucose to lactate.

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction (e.g., Recon3D for human).

- Extracellular metabolite time-series data (glucose, lactate, biomass).

- Constraint-based modeling suite (COBRA Toolbox for MATLAB/Python).

- ODE solver.

Procedure: a. Outer Dynamic Layer: Set up ODEs for external metabolites: d[Glc]/dt = -vuptake * X d[Lac]/dt = vexcretion * X dX/dt = μ * X b. Inner FBA Layer: At each ODE integration step, an FBA problem is solved where the uptake flux (vuptake) is constrained by the current external [Glc] and a Michaelis-like function: vuptake ≤ Vmax * ([Glc]/(Km+[Glc])). c. Solve: The FBA solution provides instantaneous fluxes (vuptake, vexcretion, μ) which are fed back to the ODEs. The system is integrated forward in time. d. Validation: Compare model predictions of metabolite depletion and growth phases to experimental data.

Visualizing Key Concepts and Workflows

Title: Evolution and Synthesis in Systems Biology Modeling

Title: Decision Flow: Choosing Between FBA and Kinetic Models

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Systems Biology Research

| Item/Category | Function/Description | Example (Vendor/Implementation) |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Reconstruction | Curated metabolic network defining stoichiometry for FBA. | Human: Recon3D; Yeast: Yeast8 (Public Databases) |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Suite | Software for building, simulating, and analyzing FBA models. | COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB/Python), Gurobi/CPLEX Solver |

| Kinetic Modeling Platform | Software for building, simulating, and fitting kinetic models. | COPASI, Tellurium (Python Lib), BioNetGen |

| Parameter Estimation Tool | Algorithm to fit unknown model parameters to experimental data. | COPASI's Parameter Estimation, pyPESTO (Python) |

| Time-Series Omics Data | Essential for validating and parameterizing dynamic models. | LC-MS Metabolomics, RNA-seq Time-Course Datasets |

| Fluxomic Tracers | Isotope-labeled substrates (e.g., ¹³C-Glucose) to measure in vivo fluxes for model validation. | ¹³C-Glucose, ¹⁵N-Glutamine (Cambridge Isotopes) |

| CRISPR Knockout Libraries | Enable genome-scale gene essentiality screens to test FBA predictions of lethal knockouts. | Commercial sgRNA Libraries (e.g., from Synthego) |

Within the ongoing research thesis comparing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and kinetic modeling approaches, a precise understanding of core mathematical and biochemical concepts is paramount. FBA, a constraint-based method, and kinetic modeling, a dynamic systems approach, offer distinct frameworks for analyzing metabolic networks, with significant implications for drug target identification and bioprocess optimization. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the foundational terms that differentiate and connect these two methodologies.

Stoichiometric Matrix (S)

The stoichiometric matrix is a mathematical representation of a metabolic network, central to both FBA and the formulation of kinetic models. It encodes the topology and mass balance of the system.

- Definition: A mathematical construct where rows represent metabolites (m) and columns represent biochemical reactions (n). Each element Sᵢⱼ denotes the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j. Reactants have negative coefficients, products positive.

- Thesis Context: In FBA, the matrix S is used with the assumption of steady-state (S·v = 0), enabling the prediction of flux distributions without kinetic parameters. In kinetic modeling, S is the core structural component linking reaction rates to differential equations for metabolites.

Table 1: Example Stoichiometric Matrix for a Simplified Network

| Reaction | A (mmol/gDW/h) | B (mmol/gDW/h) | C (mmol/gDW/h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| v₁: Glc → G6P | -1 | 0 | 0 |

| v₂: G6P → F6P | 1 | -1 | 0 |

| v₃: G6P → Biomass | 0.5 | 0 | -1 |

Diagram Title: Stoichiometric Matrix Encodes Network Structure

Flux Vectors (v)

Flux vectors quantify the flow of material through each reaction in a network.

- Definition: A vector v = [v₁, v₂, ..., vₙ]ᵀ, where each component vⱼ represents the net rate (e.g., mmol/gDW/h) of reaction j.

- Thesis Context: In FBA, the flux vector is the primary output, calculated by optimizing an objective function (e.g., biomass yield) subject to S·v = 0 and capacity constraints (vₘᵢₙ ≤ v ≤ vₘₐₓ). It provides a static snapshot of optimal fluxes. In kinetic modeling, the flux vector is a dynamic function of metabolite concentrations and kinetic parameters, v(t) = f([X], k).

Table 2: Flux Vector Comparison in FBA vs. Kinetic Modeling

| Characteristic | FBA Context | Kinetic Modeling Context |

|---|---|---|

| Determination | Linear/Quadratic Programming solution. | Defined by mechanistic rate laws. |

| State | Steady-state, time-invariant. | Time-dependent, dynamic. |

| Dependency | Network constraints & objective function. | Instantaneous metabolite concentrations & kinetic parameters. |

| Primary Output | Yes, the predicted flux distribution. | Intermediate variable for calculating concentration changes. |

Rate Laws

Rate laws are algebraic equations that define the instantaneous velocity of a biochemical reaction as a function of reactant concentrations and kinetic parameters.

- Definition: Mathematical expressions such as Mass-Action (v = k · [A]) or Michaelis-Menten (v = (Vₘₐₓ·[S])/(Kₘ + [S])) that describe reaction kinetics.

- Thesis Context: Rate laws are the fundamental bridge between network structure and dynamics. They are not required for FBA, which is a key distinction. Kinetic modeling critically depends on the explicit formulation of a rate law for each reaction to construct the system of ODEs.

Experimental Protocol: Determining Kinetic Parameters for a Rate Law

- Objective: Estimate Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ for an enzyme-catalyzed reaction.

- Method: In vitro assay with purified enzyme.

- Prepare a series of reaction mixtures with varying substrate concentrations ([S]).

- Initiate reactions under saturating, constant conditions (pH, T, cofactors).

- Measure initial velocity (v₀) for each [S] via spectrophotometry (NAD(P)H oxidation/reduction) or coupled assays.

- Fit v₀ vs. [S] data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using non-linear regression (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm).

- Key Controls: Include no-enzyme and no-substrate blanks. Use an enzyme concentration yielding linear progress curves.

Diagram Title: Components Defining a Reaction Flux via Rate Law

Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs)

ODEs form the dynamic core of kinetic models, describing the temporal evolution of metabolite concentrations.

- Definition: A system of equations dX/dt = S · v(X, k), where X is the vector of metabolite concentrations, S is the stoichiometric matrix, and v is the vector of rate laws dependent on X and kinetic parameters k.

- Thesis Context: This is the critical synthesis point. The ODE system dynamically integrates the network structure (S) with reaction kinetics (v). FBA explicitly avoids solving ODEs by assuming steady-state, thus requiring far less parameter data but sacrificing dynamic insight.

Table 3: Core Components of a Kinetic ODE System

| Component | Symbol | Role in ODE System | Example Value/Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolite Conc. | Xᵢ | State variable. | [Glucose] = 2.5 mM |

| Stoichiometry | Sᵢⱼ | Links flux changes to concentration changes. | -1, 0, 1 |

| Rate Law Vector | v(X,k) | Defines flux as a function of state. | v₁ = k₁·[Glc] |

| Time Derivative | dXᵢ/dt | Resulting rate of concentration change. | d[G6P]/dt = v₁ - v₂ - 0.5·v₃ |

Diagram Title: ODE System Synthesizes Structure and Kinetics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Kinetic Parameter Determination

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Purified Enzyme | Catalytic entity of interest, free from interfering cellular components, required for mechanistic study. |

| Substrate Variants | Series of concentrations of the primary reactant to probe enzyme saturation and affinity. |

| Cofactor Regeneration System | Maintains essential cofactors (e.g., NAD⁺/NADH, ATP) in active state for sustained assay activity. |

| Coupled Enzyme System | Links the primary reaction to a spectrophotometrically detectable reaction (e.g., via NADH consumption). |

| High-Precision Microplate Spectrophotometer | Enables parallel, high-throughput measurement of initial reaction velocities across multiple conditions. |

| Non-Linear Regression Software | Used to fit initial velocity data to complex rate laws and extract kinetic parameters with confidence intervals. |

From Theory to Practice: Implementing FBA and Kinetic Models in Drug Development

Step-by-Step Guide to Building a Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) for FBA

Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) methods, including Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), represent a cornerstone of systems biology for modeling metabolism. A critical advantage of FBA within the kinetic modeling debate is its ability to predict organism-scale metabolic fluxes without requiring extensive kinetic parameter data, which is often unavailable for most enzymes. FBA relies on the principle of steady-state mass balance, thermodynamic constraints, and an optimization objective (e.g., biomass maximization) to predict flux distributions. This guide details the construction of a high-quality Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM), the prerequisite for performing FBA, framing it as a scalable alternative to detailed kinetic models for applications in metabolic engineering and drug target identification.

The Model Reconstruction Pipeline

Table 1: Key Stages in GEM Reconstruction

| Stage | Primary Objective | Key Outputs | Typical Duration* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Draft Reconstruction | Generate organism-specific reaction list from genome annotation. | List of metabolic reactions, initial SBML file. | 1-4 weeks |

| 2. Network Compilation & Curation | Add transport, exchange reactions; correct gaps and dead-ends. | Stoichiometric matrix (S), compartmentalized network. | 2-6 months |

| 3. Biomass Objective Formulation | Define quantitative biomass composition reaction. | Biomass Objective Function (BOF). | 2-4 weeks |

| 4. Thermodynamic & Capacity Constraints | Define reaction directionality (reversibility) and flux bounds. | Lower/Upper bound vectors (lb, ub). | 1-3 weeks |

| 5. Validation & Iterative Refinement | Compare model predictions to experimental data (e.g., growth, ESS). | Validated, functional model (MAT/JSON/SBML). | Ongoing |

*Duration varies significantly with organism knowledge and available data.

Detailed Step-by-Step Methodology

Stage 1: Automated Draft Reconstruction

Protocol:

- Obtain Annotated Genome: Use a trusted source (e.g., NCBI RefSeq, UniProt) for the target organism's proteome and genome annotation (GFF3 file).

- Perform Metabolic Annotation: Use tools like ModelSEED, RAST, or CarveMe to map gene functions to reactions via EC numbers or MetaCyc/Gene Ontology terms.

- Generate Draft Model: These platforms output a draft SBML file containing putative metabolites, reactions, and gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations.

Stage 2: Manual Network Curation & Gap-Filling

This is the most critical and labor-intensive phase. Protocol:

- Compartmentalization: Assign metabolites to correct cellular compartments (e.g., cytosol, mitochondria, periplasm). Use literature and localization prediction tools.

- Add Exchange Reactions: Introduce reactions that allow metabolites to be taken up or secreted from the system boundary (e.g.,

EX_glc(e)). - Gap Analysis: Perform Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to identify blocked reactions. Use MEMOTE for automated quality assessment.

- Gap Resolution: Manually consult biochemical literature and databases (KEGG, MetaCyc, BRENDA) to add missing transport or enzymatic reactions. Never add a reaction without genomic evidence unless justified as a necessary "gap-fill."

Diagram 1: From genome annotation to a curated network model.

Stage 3: Formulating the Biomass Objective Function (BOF)

The BOF is a pseudo-reaction representing the drain of metabolites (amino acids, nucleotides, lipids, cofactors) at their experimentally measured ratios to produce one unit of biomass (e.g., 1 gDW). Protocol:

- Gather Composition Data: From published literature, obtain quantitative measurements of cellular macromolecular composition.

- Construct Reaction: Assemble a reaction where precursors are substrates and biomass is the product. Weights should sum to 1 g/mmol. Include ATP maintenance cost (

ATPM).

Table 2: Example Biomass Precursor Coefficients forE. coli

| Biomass Component | Metabolite ID | mmol/gDW | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | 20 L-amino acids | ~0.50* | Major |

| RNA | ATP, GTP, UTP, CTP | ~0.22* | Major |

| DNA | dATP, dGTP, dTTP, dCTP | ~0.03* | Minor |

| Lipids | Phospholipids (e.g., PE) | ~0.09* | Significant |

| Cofactors | NAD, CoA, etc. | ~0.01* | Minor |

| Maintenance | ATP (for non-growth) | ~8.39 mmol/gDW | Essential |

*Aggregate values; individual coefficients vary.

Stage 4: Applying Physico-Chemical Constraints

Define the lb and ub for each reaction v in the model.

Protocol:

- Reversibility: Set

lb = -1000andub = 1000for reversible reactions. Setlb = 0andub = 1000for irreversible reactions based on enzyme annotation. - Exchange Bounds: Set uptake (

lb) and secretion (ub) rates. For a carbon source in minimal media (e.g., glucose at 10 mM), setEX_glc(e): lb = -10, ub = 1000.

Stage 5: Model Validation & Testing

Protocol: Essential Gene Deletion (In Silico)

- Simulate Gene Knockout: Use

cobra.flux_analysis.single_gene_deletion(in COBRApy). - Calculate Growth Rate: Perform FBA maximizing biomass for each gene deletion strain.

- Compare to Experimental Data: Use publicly available essentiality datasets (e.g., from Keio collection for E. coli).

- Calculate Metrics: Determine accuracy, precision, recall of model predictions.

- Formula: Prediction Accuracy = (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN), where TP=True Positive (essential predicted & observed).

Diagram 2: The core FBA workflow using a constructed GEM.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Category | Function & Purpose | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Annotation Pipeline | Links genome to metabolic functions. | RAST, PGAP, Prokka |

| Draft Reconstruction | Automated model building from annotation. | CarveMe, ModelSEED, AuReMe |

| Model Format | Standardized model exchange format. | SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) |

| Curated Database | Reference for reaction stoichiometry & GPRs. | MetaCyc, BiGG Models, KEGG |

| Quality Testing | Automated model testing & validation. | MEMOTE (for community standards) |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB environment for FBA simulations. | COBRA Toolbox v3.0 |

| Python Environment | Popular programming environment for FBA. | COBRApy, cameo |

| Solver | Mathematical optimization engine. | Gurobi, CPLEX, GLPK |

| Experimental Validation | Phenotypic data for model validation. | Gene essentiality screens, Growth phenotyping, 13C-MFA data |

The growing need for predictive models in systems biology has highlighted the dichotomy between constraint-based and dynamic approaches. While Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) provides a robust, stoichiometry-driven framework for predicting steady-state fluxes in large-scale networks, it inherently lacks temporal resolution and regulatory details. Kinetic modeling, though more parameter-intensive, offers a dynamic, mechanistic view of metabolic and signaling pathways, crucial for understanding drug effects, cellular responses, and disease mechanisms. This guide details the construction of kinetic models, positioning this methodology as an essential complement to FBA within a comprehensive metabolic research strategy, especially where dynamics, regulation, and transient responses are critical.

Defining the Biological Pathway

The first step is the precise delineation of the system boundary and the biochemical reactions. This involves converting a conceptual pathway into a set of stoichiometric equations, including all substrates, products, enzymes, and modifiers.

Example: Core Glycolytic Pathway Definition A minimal model might focus on the conversion of Glucose to Pyruvate.

- HK: Glucose + ATP → G6P + ADP

- PGI: G6P ⇌ F6P

- PFK: F6P + ATP → FBP + ADP

- ALD: FBP ⇌ DHAP + GAP

- TPI: DHAP ⇌ GAP

- GAPDH: GAP + NAD⁺ + Pi ⇌ 13BPG + NADH + H⁺

- PGK: 13BPG + ADP ⇌ 3PG + ATP

- PGM: 3PG ⇌ 2PG

- ENO: 2PG ⇌ PEP

- PK: PEP + ADP → Pyruvate + ATP

Formulating the Kinetic Rate Laws

Each reaction requires a mechanistic or approximative rate law. For enzyme-catalyzed reactions, Michaelis-Menten or Hill-type equations are common. Allosteric regulation requires adding modifier terms.

Table 1: Common Kinetic Rate Laws for Model Parameterization

| Rate Law Name | Mathematical Form | Key Parameters | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Irreversible Michaelis-Menten | v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S]) | Vmax, Km | Simple enzymatic conversion |

| Reversible Michaelis-Menten | v = (Vf * ([S]/KS) - Vr * ([P]/KP)) / (1 + [S]/KS + [P]/KP) | Vf, Vr, KS, KP | Near-equilibrium reactions |

| Hill Equation (Activation) | v = Vmax / (1 + (KA / [A])^n) | Vmax, KA, n (Hill coeff.) | Cooperative allosteric activation |

| Competitive Inhibition | v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km (1 + [I]/K_i) + [S]) | Vmax, Km, K_i | Inhibition by a substrate analog |

| Mass Action | v = k * [A]^x * [B]^y | k (rate constant) | Elementary biochemical steps |

Parameter Estimation and Model Calibration

This is the most critical and challenging phase. Parameters (Vmax, Km, etc.) are derived from literature, direct experimentation, or fitting to time-course data.

Experimental Protocol: Determining Michaelis-Menten Parameters In Vitro

- Objective: Determine Km and Vmax for Hexokinase (HK).

- Reagents: Purified HK enzyme, D-Glucose, ATP, MgCl₂, NADP⁺, Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PDH) (for coupled assay), reaction buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, pH 7.5).

- Procedure:

- Prepare a master mix containing constant, saturating ATP, Mg²⁺, NADP⁺, G6PDH, and buffer.

- Aliquot the master mix into a 96-well plate.

- Initiate reactions by adding a range of Glucose concentrations (e.g., 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0 mM).

- Immediately monitor the increase in NADPH absorbance at 340 nm using a plate reader for 2-5 minutes.

- Calculate initial velocities (v₀) from the linear slope of absorbance vs. time.

- Data Analysis: Plot v₀ vs. [Glucose]. Fit data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])) using non-linear regression software (e.g., Prism, Python SciPy) to extract Km and Vmax.

Model Simulation, Validation, and Analysis

The parameterized model, expressed as a set of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs), is simulated using numerical solvers.

Table 2: Comparison of FBA and Kinetic Modeling Approaches

| Feature | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Optimization of an objective (e.g., growth) within stoichiometric & capacity constraints | Numerical integration of differential equations based on reaction kinetics |

| Temporal Resolution | Steady-state only (no time dimension) | Explicitly dynamic (transient and steady-states) |

| Parameter Needs | Requires stoichiometry, uptake/secretion rates, growth objective | Requires kinetic constants (Km, Vmax, k), initial concentrations |

| Regulatory Insight | Indirect (via constraints) | Direct (via kinetic laws and modifiers) |

| Scale | Genome-scale models (1000s of reactions) | Typically small to medium-scale pathways (10s-100s of reactions) |

| Key Application | Predicting growth phenotypes, flux distributions | Predicting metabolite dynamics, dose-response, drug inhibition |

Experimental Protocol: Model Validation via Metabolite Time-Course

- Objective: Validate a glycolysis model by comparing simulated vs. experimental metabolite levels.

- Cell Culture & Perturbation: Use a controlled bioreactor. Rapidly perturb the system (e.g., switch from high to low glucose).

- Sampling & Quenching: At precise time points (e.g., 0, 15s, 30s, 1, 2, 5, 10, 30 min), rapidly quench metabolism (cold methanol/water).

- Metabolite Extraction & Analysis: Extract intracellular metabolites. Quantify glycolytic intermediates (G6P, F6P, FBP, PEP, etc.) using LC-MS/MS.

- Simulation & Comparison: Use the identical perturbation as an input to the kinetic model. Simulate the time courses. Compare simulated concentrations to experimental data quantitatively (e.g., using Sum of Squared Residuals).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Kinetic Model Construction & Validation

| Item | Function in Kinetic Modeling | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS System | High-sensitivity, quantitative measurement of metabolite time-courses for model parameterization/validation. | Agilent 6470, Sciex QTRAP 6500+ |

| Microplate Reader | Rapid kinetic assays for determining enzyme parameters (Vmax, Km) in vitro. | BMG Labtech CLARIOstar, BioTek Synergy H1 |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (e.g., ¹³C-Glucose) | Enable measurement of metabolic fluxes for model constraint and validation. | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories |

| Rapid Sampling & Quenching Devices | Capture metabolic snapshots at sub-second resolution for dynamic models. | BioScope (Cytiva), fast-filtration manifolds |

| Enzyme Assay Kits | Standardized, optimized reagents for determining specific enzyme activities. | Sigma-Aldrich, Cayman Chemical |

| ODE Simulation Software | Numerical integration and parameter estimation. | COPASI, MATLAB with SBtoolbox2, Python (SciPy, Tellurium) |

| Curated Kinetic Databases | Source for initial parameter estimates and thermodynamic constants. | BRENDA, SABIO-RK, MetaCyc |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Tools | Enable precise, tunable perturbation of enzyme expression levels in vivo for model testing. | Various sgRNA libraries, dCas9-KRAB/VP64 |

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide on applying computational modeling to target identification (ID) and mechanism of action (MoA) studies, framed within a research thesis comparing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and kinetic modeling approaches in pharmaceutical development.

Target ID and MoA elucidation are foundational to modern drug discovery. The choice between constraint-based (e.g., FBA) and kinetic modeling is critical, dictated by the biological question and available data. FBA utilizes stoichiometric networks and optimization under constraints, ideal for large-scale metabolic networks with incomplete kinetic data. Kinetic modeling employs detailed differential equations, requiring precise kinetic parameters but enabling dynamic, quantitative predictions of perturbation effects.

Methodological Comparison: FBA vs. Kinetic Modeling

The table below summarizes the core quantitative distinctions between these approaches in the context of Target ID/MoA.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of FBA and Kinetic Modeling for Target ID/MoA

| Aspect | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Steady-state flux optimization via linear programming. | Time-dependent integration of differential equations. |

| Network Scale | Genome-scale (1000s of reactions). | Small to medium-scale pathways (10s-100s of reactions). |

| Data Requirement | Stoichiometry, growth/uptake rates, optional gene KO data. | Detailed kinetic constants (Km, Vmax), metabolite concentrations. |

| Primary Output | Steady-state reaction flux distribution. | Metabolite/RPP concentration time-courses. |

| Target Prediction | Essential genes/reactions via in silico knockout. | Sensitivity analysis (e.g., control coefficients). |

| Key Strength | Scalability, minimal parameter needs. | Dynamic, quantitative prediction of perturbation effects. |

| Key Limitation | No dynamics, requires pseudo-steady-state assumption. | Parameter uncertainty, difficult to scale. |

| Common Software | COBRA Toolbox, Escher, CellNetAnalyzer. | COPASI, SBML-simulators, PySCeS. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout for FBA-Predicted Essential Gene Validation

Objective: Validate computational predictions of gene essentiality from FBA in silico knockout simulations.

- Design: Design sgRNAs targeting the gene of interest and a non-targeting control using established design tools (e.g., CRISPick).

- Delivery: Transfect target cell line (e.g., HEK293, cancer cell line) with lentiviral vectors encoding Cas9 and sgRNA.

- Selection: Apply puromycin (or relevant antibiotic) selection for 72 hours to enrich transfected cells.

- Phenotypic Assay: Seed cells in 96-well plates. Monitor cell viability/proliferation over 5-7 days using a real-time cell analyzer (e.g., xCELLigence) or endpoint ATP-based assays (CellTiter-Glo).

- Analysis: Compare growth curves of gene knockout vs. control. Statistical significance (p<0.01) in growth impairment confirms essentiality.

Protocol 2: Phospho-Proteomics for Kinetic Model Calibration

Objective: Generate quantitative, time-resolved data to parameterize and validate a kinase pathway kinetic model.

- Stimulation & Lysis: Serum-starve cells for 24h. Stimulate with ligand (e.g., EGF, 100 ng/mL) in staggered time courses (0, 2, 5, 15, 30, 60 min). Lyse cells in urea-based buffer with phosphatase/protease inhibitors.

- Digestion & Labeling: Reduce, alkylate, and digest lysates with trypsin. Label peptides with TMTpro 16-plex isobaric tags.

- Phosphopeptide Enrichment: Enrich phosphorylated peptides using Fe-IMAC or TiO2 magnetic beads.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Fractionate peptides by basic pH reversed-phase HPLC, followed by nanoLC-MS/MS on an Orbitrap Eclipse platform.

- Data Processing: Identify and quantify phosphopeptides using search engines (e.g., Sequest HT) and platforms (e.g., Proteome Discoverer 3.0). Normalize to time-zero controls.

- Model Integration: Use time-course phospho-site intensities as constraints to fit kinetic rate constants in models built with software like COPASI.

Essential Visualizations

Title: FBA Workflow for Target Identification

Title: Integrated PK/PD & Kinetic MoA Model

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Target ID/MoA Experiments

| Item | Function & Application | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Kit | Enables precise gene knockout for validating computational predictions of gene essentiality. | Thermo Fisher TrueCut Cas9 Protein v2 & synthetic sgRNA. |

| Isobaric Mass Tags (TMTpro) | Multiplexed quantitative proteomics; allows simultaneous measurement of phospho-proteome across multiple time points/conditions for kinetic model calibration. | Thermo Fisher TMTpro 16plex Label Reagent Set. |

| Phosphopeptide Enrichment Beads | Selective enrichment of phosphorylated peptides from complex digests prior to MS analysis. | Thermo Fisher TiO2 Magnetic Beads. |

| Real-Time Cell Analyzer | Label-free, continuous monitoring of cell proliferation and viability for phenotypic validation of targets. | Agilent xCELLigence RTCA. |

| ATP-Based Viability Assay | Sensitive, endpoint luminescent readout of cell viability based on cellular ATP levels. | Promega CellTiter-Glo 3D. |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling and simulation (FBA). Essential for building and analyzing genome-scale models. | Open-source software suite. |

| COPASI | Standalone software for kinetic modeling, simulation, and analysis of biochemical networks. | Open-source software. |

Predicting Drug-Induced Metabolic Shifts and Off-Target Effects

This whitepaper examines computational frameworks for predicting metabolic dysregulation caused by pharmacological agents, framed within an ongoing research thesis comparing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and kinetic modeling approaches. The central thesis posits that while constraint-based FBA provides a robust, genome-scale platform for predicting steady-state metabolic shifts, kinetic modeling is indispensable for elucidating transient off-target effects and time-dependent phenomena critical to drug safety profiling. The integration of both paradigms is essential for a comprehensive in silico predictive toxicology platform.

Core Methodological Approaches: FBA vs. Kinetic Modeling

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a constraint-based, stoichiometric modeling approach that computes steady-state reaction fluxes by optimizing a cellular objective (e.g., biomass maximization) subject to mass-balance and capacity constraints. Its application in drug prediction involves simulating gene/protein knockouts or inhibition constraints to predict resultant flux redistributions.

Kinetic Modeling employs ordinary differential equations (ODEs) based on enzyme mechanisms and kinetic parameters (e.g., V~max~, K~m~) to dynamically simulate metabolite concentrations and reaction velocities over time. This approach is critical for modeling the transient inhibition of off-target enzymes and the consequent metabolite accumulation or depletion.

Table 1: Comparison of FBA and Kinetic Modeling for Drug Effect Prediction

| Feature | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Core Basis | Stoichiometry & Linear Programming | Enzyme Kinetics & ODEs |

| Primary Output | Steady-state Flux Distribution | Time-course of Metabolite Concentrations |

| Scale | Genome-scale Models (1000s of reactions) | Smaller, curated pathways (10s-100s of reactions) |

| Data Requirements | Stoichiometric matrix, Growth/uptake rates | Kinetic parameters, Initial metabolite concentrations |

| Strength for Drug Prediction | Identifying systemic redistribution & alternate pathways | Modeling transient inhibition & feedback loops |

| Key Limitation | Cannot predict metabolite levels or dynamics | Kinetic parameters often unknown or in vitro |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol 3.1: Metabolomics for Validating Predicted Shifts

Objective: To experimentally measure drug-induced metabolic shifts for comparison with in silico predictions. Materials: Target cell line, drug compound, LC-MS/MS system, quenching solution (e.g., 60% methanol at -40°C). Procedure:

- Culture cells in triplicate and treat with drug at IC~50~ and vehicle control for 4h and 24h.

- Rapidly quench metabolism at each time point using cold quenching solution.

- Extract intracellular metabolites. Use a biphasic solvent system (e.g., methanol/chloroform/water).

- Analyze extracts via untargeted LC-MS/MS. Use reversed-phase and HILIC chromatography.

- Process raw data (peak picking, alignment, annotation using libraries like HMDB or METLIN).

- Perform statistical analysis (e.g., PCA, fold-change) to identify significantly altered metabolites.

- Compare the list of significantly altered metabolites (p<0.05, fold-change >2) against the model-predicted changes in flux or concentration.

Protocol 3.2: Off-Target Binding Affinity Assay (CETSA)

Objective: To experimentally identify off-target protein interactions of a drug compound. Materials: Cell lysate or intact cells, drug compound, quantitative proteomics setup (e.g., TMT labeling, LC-MS/MS), heating block. Procedure:

- Divide cell lysate or intact cells into aliquots.

- Treat aliquots with vehicle or drug compound (e.g., 10 µM) for 15-30 minutes.

- Heat each aliquot at a range of temperatures (e.g., 37°C to 67°C in increments) for 3 minutes.

- Cool samples, then centrifuge to separate soluble protein from aggregates.

- Digest proteins in the soluble fraction, label with isobaric tandem mass tags (TMT).

- Analyze via LC-MS/MS. Quantify protein abundance in each sample.

- For each protein, calculate the melting curve shift induced by the drug. A stabilizing shift indicates binding.

- Integrate identified off-target binders into the kinetic model as additional inhibition constraints.

Integrated Workflow for Prediction

Integrated Prediction Workflow: FBA & Kinetic Modeling

Key Off-Target Signaling Pathways

A common source of metabolic off-target effects is the inadvertent modulation of cellular stress and growth signaling pathways.

Common Off-Target Signaling & Metabolic Outcomes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function & Application | Example/Vendor |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | Constraint-based simulation backbone for FBA. Provides stoichiometric matrix and gene-reaction rules. | Recon3D, Human1, MetaCyc Database |

| Kinetic Parameter Database | Source of enzyme kinetic constants (Km, kcat) for building and parameterizing ODE models. | BRENDA, SABIO-RK, EMPATH |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (e.g., ¹³C-Glucose) | Enables experimental fluxomics via LC-MS to measure pathway activity and validate FBA predictions. | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories |

| Isobaric Mass Tag Kits (TMT/iTRAQ) | For multiplexed quantitative proteomics in CETSA and phosphoproteomics to identify off-targets. | Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| CETSA/Proteomics Kits | Optimized buffers and protocols for cellular thermal shift assays coupled with mass spectrometry. | Pelago Biosciences |

| Metabolomics Standards & Kits | Internal standards and extraction kits for reproducible, broad-coverage metabolomics profiling. | Biocrates, Avanti Polar Lipids |

| ODE Solver Software | Numerical computing environment for building and simulating kinetic models. | COPASI, MATLAB with SBtoolbox2, PySCeS |

| FBA Simulation Platform | Software for constraint-based modeling, simulation, and analysis. | COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB/Python), Escher |

| Pathway Visualization Tool | For rendering and annotating predicted metabolic and signaling networks. | Cytoscape, Escher, PathVisio |

Data Presentation: Quantitative Case Study

Table 3: Case Study - Predicting Effects of a Putative Hexokinase 2 Inhibitor

| Predicted Metric | FBA-Based Prediction | Kinetic Model Prediction | Experimental Validation (Metabolomics) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Uptake Flux | ↓ 45% | ↓ 60% at 1h, ↓ 48% at steady-state | ↓ 52% (24h) |

| Lactate Secretion | ↓ 38% | Rapid ↓ 70% at 1h, then partial recovery | ↓ 41% (24h) |

| ATP Pool | No direct prediction | Transient ↓ 30% at 30min, recovers via OXPHOS | ↓ 15% (4h), normalized at 24h |

| G6P/G1P Ratio | No concentration prediction | ↑ 2.8-fold sustained | ↑ 3.1-fold (4h) |

| Off-Target Effect Identified | None (target-specific constraint) | GK Inhibition predicted via binding affinity sim. | GK activity ↓ 40% (CETSA + enzymatic assay) |

| Key Insight Provided | Systemic flux rerouting to mitochondrial metabolism. | Transient energy crisis & feedback via GK off-target. | Confirms both primary and off-target effects. |

The pursuit of novel antimicrobial targets is a critical challenge in the face of escalating antibiotic resistance. This case study explores the application of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), a constraint-based metabolic modeling approach, within the broader research context comparing FBA with kinetic modeling for target discovery. While kinetic models rely on detailed enzyme mechanism parameters—often scarce for pathogenic organisms—FBA leverages genomic and stoichiometric data to predict system-level metabolic fluxes under steady-state conditions. This makes FBA particularly powerful for the rapid in silico identification of essential metabolic reactions that can serve as potential drug targets, especially in emerging or less-characterized pathogens.

Core FBA Methodology for Target Identification

FBA calculates the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network to predict an organism's growth rate or a specific objective function. The model is defined by the stoichiometric matrix S, where S_ij represents the coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j. The core mathematical formulation is:

Maximize: Z = cᵀv (Objective function, e.g., biomass production) Subject to: S·v = 0 (Mass balance constraints) vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax (Capacity constraints)

The protocol for antimicrobial target discovery follows a systematic workflow.

FBA Workflow for Antimicrobial Target Discovery

Experimental Validation Protocols

In SilicoGene Essentiality Screen

Purpose: To predict reactions whose knockout abolishes microbial growth. Protocol:

- Load the genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) (e.g., in COBRApy or Matlab COBRA Toolbox).

- Set the objective function to the biomass reaction.

- For each reaction j in the model:

- Set the lower and upper bounds of v_j to zero (simulating knockout).

- Perform FBA to calculate the maximal biomass yield.

- If the predicted growth rate is below a threshold (e.g., <5% of wild-type), flag reaction j as essential.

- Compile a list of essential reactions.

In VitroEssentiality Validation via CRISPRi or Transposon Mutagenesis

Purpose: To confirm in silico predictions experimentally. Protocol (CRISPRi in Bacteria):

- Design sgRNAs targeting the promoter region of the gene encoding the essential enzyme.

- Clone sgRNA into a dCas9-repression vector with an inducible promoter.

- Transform the construct into the target bacterial strain.

- Plate serial dilutions of induced (+repressor) and uninduced cultures on solid media.

- Compare colony-forming units (CFU) after 24-48 hours. A significant reduction (>2-log) in CFU for induced cultures confirms gene essentiality.

Case Study Data: Target Discovery inMycobacterium tuberculosis

A recent study (2023) applied an updated GEM of M. tuberculosis (iEK1011 2.0) to identify targets under different nutrient conditions. Key quantitative findings are summarized below.

Table 1: Predicted Essential Metabolic Reactions in M. tuberculosis under Different In Silico Conditions

| Pathway | Reaction ID (Gene) | Aerobic Growth (Rich Media) | Hypoxic (Persistence) | Essentiality in Human Metabolism (HM) | Potential Selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall Synthesis | DAPAAT (dapA) | Essential | Essential | Not Present | High |

| Folate Synthesis | DHFS (folC) | Essential | Essential | Present (Diff. Enzyme) | Medium |

| Mycolic Acid Synthesis | FAS-II (fabH) | Essential | Conditional | Not Present | High |

| TCA Cycle | ACL (acl) | Non-essential | Essential | Present | Low |

| Cholesterol Catabolism | HsaC (hsaC) | Non-essential | Essential (in vivo) | Not Present | High |

Table 2: Comparison of Modeling Approaches for Antimicrobial Target Discovery

| Feature | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirement | Genome sequence, stoichiometry, growth/uptake rates | Detailed kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax), metabolite concentrations |

| Time to Model Build | Weeks-Months | Months-Years |

| Predictive Output | System-wide flux distribution, growth yield | Dynamic metabolite concentrations, transient fluxes |

| Best for Target ID | Genome-wide essentiality screens, condition-specific vulnerabilities | Pathway-specific allosteric targets, drug synergy analysis |

| Key Limitation | Lacks regulatory dynamics, assumes optimality | Parameters often unknown for pathogens, difficult to scale |

Table 3: Essential Materials for FBA-Driven Antimicrobial Discovery

| Item | Function & Application in Study |

|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB) / COBRApy (Python) | Software suites for building, constraining, and simulating constraint-based metabolic models. Enables FBA and in silico knockout. |

| KBase (kbase.us) | Cloud platform providing tools and pipelines for genome-scale model reconstruction from annotated genomes. |

| MEMOTE Suite | Open-source tool for standardized quality assessment and testing of genome-scale metabolic models. |

| dCas9 Repression Vector (e.g., pAN6) | Plasmid for CRISPR-interference (CRISPRi) essentiality validation in bacteria; allows inducible, tunable gene knockdown. |

| Transposon Mutagenesis Library | Saturated mutant library (e.g., via Himar1 mariner) for genome-wide experimental essentiality profiling (Tn-seq). |

| Defined Minimal Media Kits | For in vitro validation of condition-specific essentiality predictions from FBA (e.g., under hypoxia, nutrient limitation). |

Pathway Visualization of a Discovered Target

The enzyme DAPAAT (encoded by dapA) in the diaminopimelate (DAP) pathway, identified as a consistently essential target in Table 1, is visualized below. DAP is a crucial lysine precursor in bacterial cell wall synthesis, absent in humans.

Diaminopimelate Pathway and dapA Target Inhibition

This case study demonstrates that FBA is a uniquely scalable and efficient tool for the de novo discovery of antimicrobial targets, especially when kinetic data is unavailable. Its strength lies in rapidly generating testable hypotheses about gene essentiality across an entire metabolic network under various in vivo-like conditions. Within the broader thesis contrasting modeling approaches, FBA provides the critical first pass—identifying vulnerable choke points in metabolism—which can then be studied in greater mechanistic detail using kinetic models to understand inhibition dynamics and optimize drug design. The integration of both approaches represents a powerful future direction for rational antimicrobial discovery.

This case study is framed within a broader research thesis comparing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and kinetic modeling approaches for understanding cancer metabolism. FBA, a constraint-based method, predicts optimal metabolic fluxes under steady-state assumptions but lacks dynamic and regulatory details. In contrast, kinetic modeling employs enzyme kinetics and differential equations to capture the dynamic, time-dependent behavior of metabolic networks, including allosteric regulation and metabolite concentrations. The Warburg Effect—the propensity of cancer cells to favor glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation even under normoxia—presents an ideal case for highlighting kinetic modeling's superiority. Its complex, multi-level regulation (transcriptional, post-translational, allosteric) involving key nodes like HK2, PFK1, PKM2, and LDHA is poorly captured by stoichiometric FBA but can be quantitatively dissected through kinetic models to identify precise therapeutic intervention points.

Core Kinetic Model of Central Carbon Metabolism in Cancer