Enzyme Mechanisms in Natural Product Biosynthesis: From Discovery to Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the enzymatic machinery responsible for the synthesis of bioactive natural products, a critical source of modern therapeutics.

Enzyme Mechanisms in Natural Product Biosynthesis: From Discovery to Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the enzymatic machinery responsible for the synthesis of bioactive natural products, a critical source of modern therapeutics. It explores foundational concepts of biosynthetic pathways, highlights cutting-edge methodological advances in enzyme discovery and engineering, and discusses strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing biocatalytic processes. By comparing and validating different enzymatic approaches, this resource equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to harness and engineer these biological catalysts for the efficient and sustainable production of complex molecules, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and development.

The Architectural Blueprint: Core Enzymatic Systems in Natural Product Assembly

Core Enzyme Mechanisms and Domain Architectures

Natural products, with their immense structural diversity and potent biological activities, are primarily synthesized by a few key classes of biosynthetic enzymes. Among these, polyketide synthases (PKSs), nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), and terpene synthases (TSs) represent sophisticated molecular assembly lines that generate complex chemical scaffolds through distinct biochemical logic. Understanding their mechanisms provides the foundation for engineering novel bioactive compounds in drug development.

Polyketide Synthases (PKSs)

Polyketide synthases are multidomain enzymes that construct polyketides, a class of natural products including clinically valuable compounds like erythromycin (antibacterial) and rapamycin (immunosuppressant) [1]. PKSs operate on a biosynthetic logic analogous to fatty acid synthases, utilizing acyl-CoA thioesters as building blocks and controlling the degree of β-carbon modification during each chain elongation cycle [1].

Type I PKSs are large, multimodular proteins where each module is responsible for one round of chain elongation and modification. Each minimal elongation module contains three core domains [1] [2]:

- Ketosynthase (KS): Catalyzes decarboxylative condensation between the growing polyketide chain and an incoming extender unit.

- Acyltransferase (AT): Selects and loads the specific extender unit (e.g., malonyl-CoA, methylmalonyl-CoA) onto the ACP.

- Acyl Carrier Protein (ACP): Carries the growing polyketide chain via a phosphopantetheine prosthetic arm.

Additional modifying domains within PKS modules control the oxidation state of the β-carbon, introducing structural diversity:

- Ketoreductase (KR): Reduces the β-keto group to a hydroxyl group.

- Dehydratase (DH): Eliminates water to form an α,β-unsaturated bond.

- Enoylreductase (ER): Reduces the double bond to a fully saturated methylene group.

Type II PKSs utilize discrete, monofunctional proteins that operate iteratively, typically producing aromatic polyketides [1]. Type III PKSs (chalcone synthase-like) directly use acyl-CoA substrates without ACP domains and generate simpler aromatic structures [1].

Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPSs)

Nonribosomal peptide synthetases are multimodular megaenzymes that assemble structurally complex peptides, such as the antibiotic vancomycin and the immunosuppressant cyclosporin, without the direct template of mRNA [1] [2]. The NRPS assembly line is organized into modules, each responsible for incorporating a single amino acid (or other acyl monomer) into the final peptide product [3].

Each minimal elongation module contains three core domains [2] [3]:

- Adenylation (A) Domain: Selects and activates the specific amino acid substrate as an aminoacyl-AMP intermediate.

- Peptidyl Carrier Protein (PCP): Carries the activated amino acid and the growing peptide chain via a phosphopantetheine arm.

- Condensation (C) Domain: Catalyzes the formation of the peptide bond between the upstream donor peptide and the downstream acceptor amino acid.

The C domain is a core catalytic domain with a pseudo-dimeric structure featuring a conserved active site motif (HHxxxDG) [3]. It acts as a secondary gatekeeper, ensuring correct substrate pairing during peptide elongation, and its mechanism involves precise positioning of the nucleophilic amine from the acceptor substrate for attack on the donor substrate's thioester carbonyl [3].

Additional auxiliary domains further diversify the final peptide structure:

- Epimerization (E) Domain: Converts L-amino acids to D-amino acids.

- Heterocyclization (Cy) Domain: Catalyzes the formation of oxazolines or thiazolines.

- Methyltransferase (M) Domain: Introduces N- or O-methyl groups.

- Thioesterase (TE) Domain: Typically located in the termination module, it releases the full-length peptide product, often through hydrolysis or macrocyclization [2] [3].

Terpene Synthases (TSs)

Terpene synthases generate the most structurally diverse family of natural products, the terpenoids, from simple C5 isoprene units [4]. All terpenoids are constructed from dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) and isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP), which are condensed into linear prenyl diphosphates of various lengths (e.g., GPP, FPP, GGPP) [4].

Canonical TSs are divided into two classes based on their structure and reaction-initiating mechanism [4]:

- Class I TSs: Typically employ a metal-dependent ionization of the prenyl diphosphate substrate to generate a carbocation, initiating cyclization.

- Class II TSs: Generally catalyze protonation of an epoxide or olefin to initiate cyclization.

These enzymes mediate complex carbocation-based cyclization and rearrangement cascades, where the vast structural diversity of terpenoids arises from the stabilization of transient carbocations and controlled quenching of the reaction [4]. The substrate folding within the active site and specific interactions with active site residues dictate the final cyclic skeleton.

Recently, the discovery of non-canonical TSs has expanded the field. These enzymes perform terpene synthase-like cyclization reactions but do not resemble canonical TSs in sequence or structure. They can belong to other enzyme families, including prenyltransferases, methyltransferases, cytochrome P450s, and flavin-dependent oxidocyclases, utilizing distinctive reaction mechanisms for terpene biosynthesis [4].

Table 1: Core Domains in PKS and NRPS Assembly Lines

| Enzyme Class | Domain | Core Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PKS | Ketosynthase (KS) | Chain elongation via decarboxylative condensation | Determines chain length and processes intermediates [1] |

| Acyltransferase (AT) | Selects and loads extender unit | Specificity for malonyl-CoA, methylmalonyl-CoA, etc. [1] | |

| Acyl Carrier Protein (ACP) | Carries growing polyketide chain | Contains phosphopantetheine prosthetic arm [1] | |

| NRPS | Adenylation (A) | Selects and activates amino acid substrate | Determines amino acid incorporated; has 10 residue specificity code [2] [3] |

| Peptidyl Carrier Protein (PCP) | Carries activated amino acid/peptide | Contains phosphopantetheine prosthetic arm [3] | |

| Condensation (C) | Forms peptide bond between modules | HHxxxDG active site motif; has donor/acceptor specificity [3] |

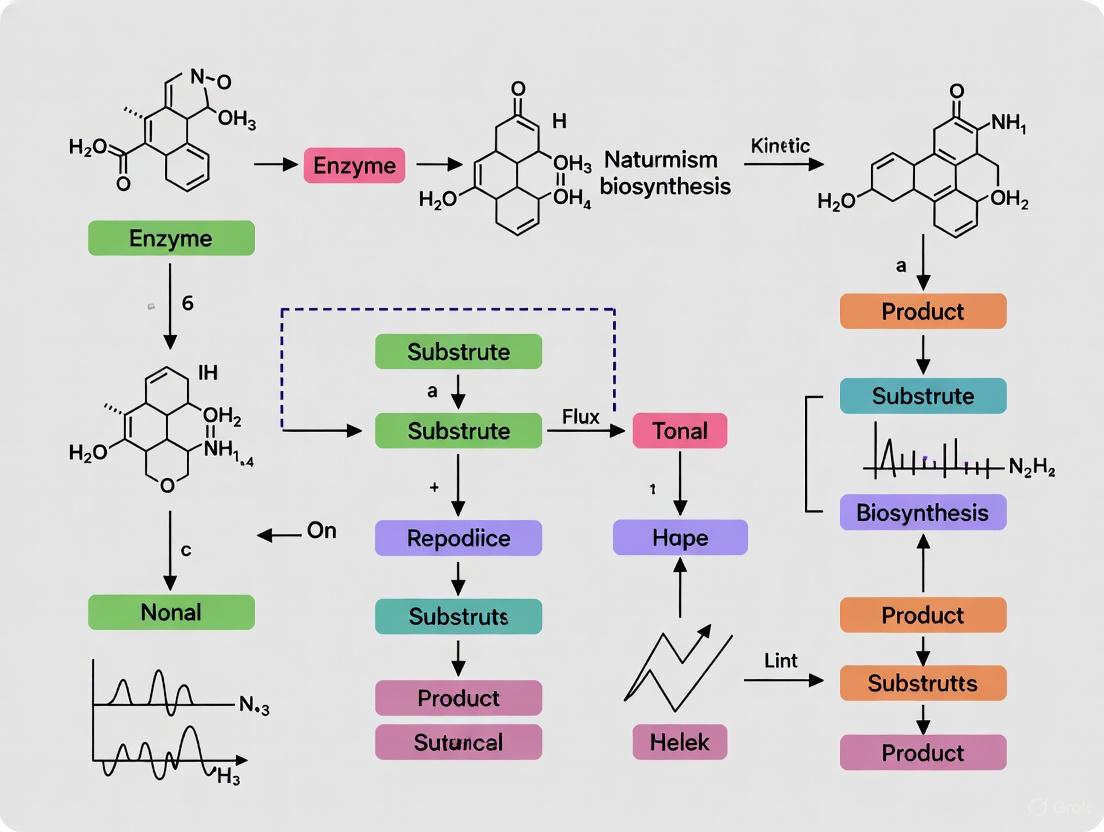

Diagram 1: Core catalytic logic of PKS, NRPS, and Terpene Synthase enzymes. PKS and NRPS function as assembly lines with carrier proteins, while TSs mediate carbocation-driven cyclization.

Quantitative Profiling of Biosynthetic Potential

Genome mining has revolutionized the discovery of natural products by enabling researchers to profile the biosynthetic potential of organisms in silico before embarking on laborious chemical isolation. This approach relies on identifying Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)—genomic loci where genes encoding for the biosynthetic machinery of a secondary metabolite are co-localized [5] [6].

Advanced bioinformatics tools like antiSMASH are used to systematically identify and annotate BGCs in genomic data [6]. The backbone genes within these clusters determine the class of natural product produced. For instance, the presence of PKS and NRPS genes indicates the potential to produce polyketides and nonribosomal peptides, respectively [5].

Table 2: Genome Mining Reveals PKS/NRPS Diversity in Select Genera

| Organism / Genus | Total PKS & NRPS Gene Clusters | PKS Clusters (Type I/II/III) | NRPS Clusters | Hybrid PKS-NRPS Clusters | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternaria spp. (Fungi) | Avg. 29 BGCs per genome (total 6,323 BGCs from 187 genomes) | Information not specified | Information not specified | Information not specified | BGC distribution correlates with phylogeny; AOH/AME toxin GCF found in sections Alternaria & Porri. | [5] |

| Phytohabitans flavus (Actinomycete) | 10 | 2 (I), 1 (III), 1 (I/III) | 3 | 3 | 9.6 Mb genome; majority of clusters annotated for unknown chemistries. | [6] |

| Phytohabitans rumicis (Actinomycete) | 14 | 3 (I), 3 (III) | 6 | 2 | 10.7 Mb genome; highlights genus as a source for novel compounds. | [6] |

| Phytohabitans houttuyneae (Actinomycete) | 18 | 5 (I), 4 (III) | 7 | 2 | 11.3 Mb genome; possesses the highest number of clusters among the four species. | [6] |

| Phytohabitans suffuscus (Actinomycete) | 14 | 3 (I), 3 (III) | 6 | 2 | 10.2 Mb genome; potential for diverse polyketides and nonribosomal peptides. | [6] |

Experimental Methodologies for Pathway Characterization

Characterizing the function of biosynthetic enzymes and elucidating entire pathways requires a combination of genetic, biochemical, and analytical techniques. The following protocols represent key methodologies used in the field.

Protocol: In vivo Gene Inactivation and Metabolite Profiling inC. elegans

This protocol was used to map the biosynthesis of nemamides, hybrid polyketide-nonribosomal peptides in Caenorhabditis elegans, revealing a unique intermediate trafficking mechanism [7].

Objective: To determine the function of specific NRPS/PKS domains by disrupting their activity in a metazoan host and analyzing the resulting metabolic changes.

Key Reagents and Materials:

- CRISPR-Cas9 System: For precise genome editing to introduce point mutations into target genes (e.g., nrps-1, pks-1).

- High-Density Axenic Culture Media: For large-scale cultivation of C. elegans worms (2-3 liters yielding 3-5 g of worms).

- Solvents for Metabolite Extraction: Ethyl acetate or similar organic solvents.

- Chromatography Equipment: For partial purification of intermediates, including solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) systems.

- High-Resolution LC-MS/MS System: Equipped with a C18 reverse-phase column for separation and a mass spectrometer for detection and identification.

Procedure:

- Gene Inactivation: Use CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce specific point mutations into catalytic residues of target domains (e.g., serine in TE domains, histidine in C domains) in the C. elegans genome [7].

- Large-Scale Cultivation: Grow wild-type and mutant worm strains in high-density axenic cultures to obtain sufficient biomass for metabolic analysis.

- Metabolite Extraction: Homogenize the worm pellets and extract metabolites using organic solvents. Concentrate the extracts under reduced pressure.

- Partial Purification: Subject the crude extracts to two or more chromatographic steps (e.g., SPE followed by HPLC). Monitor fractions for compounds of interest using the characteristic ultraviolet (UV) spectrum of the target metabolites (e.g., triene/tetraene moiety for nemamides) [7].

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze purified fractions using high-resolution LC-MS/MS. Identify accumulated biosynthetic intermediates by their accurate mass and MS/MS fragmentation patterns, comparing them to wild-type profiles [7].

Expected Outcome: Successful domain inactivation results in the abolition of the final natural product and the accumulation of earlier biosynthetic intermediates, allowing the function of the targeted domain to be mapped within the pathway.

Protocol: Cell-Free Biosynthetic Pathway Prototyping

Cell-free synthetic biology provides a bottom-up, open platform for rapidly characterizing biosynthetic enzymes and assembling pathways without the constraints of the cell membrane [8].

Objective: To express PKS, NRPS, or TS pathways in a cell-free system to produce, characterize, and optimize natural product synthesis.

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) System: A commercially available or lab-made extract (e.g., from E. coli) containing transcription/translation machinery, energy sources, and cofactors.

- Plasmid DNA: Encoding the target biosynthetic gene cluster or individual enzymes under a strong promoter.

- Substrates and Cofactors: Acyl-CoAs (for PKS), amino acids (for NRPS), isoprenyl diphosphates (for TS), ATP, NADPH, and Mg²âº.

- Analytical Instrumentation: LC-MS or UHPLC-HRMS for detecting and identifying synthesized metabolites.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Combine the CFPS mix with plasmid DNA encoding the biosynthetic genes and all necessary substrates and cofactors in a single tube or multi-well plate.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction for several hours at a controlled temperature (e.g., 30-37°C) with shaking to allow for protein expression and catalytic activity.

- Reaction Termination: Stop the reaction by adding a solvent like methanol or acetonitrile.

- Metabolite Analysis: Centrifuge the mixture to remove precipitated protein and analyze the supernatant directly by LC-MS to detect newly synthesized natural products.

Expected Outcome: The in vitro production of the target natural product or biosynthetic intermediates, confirming the activity of the expressed enzymes and enabling rapid optimization of pathway components.

Diagram 2: A generalized workflow for characterizing natural product biosynthetic pathways, integrating genome mining with genetic and biochemical validation.

Table 3: Key Resources for PKS, NRPS, and Terpene Synthase Research

| Category | Resource / Reagent | Specific Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | antiSMASH | Identifies and annotates biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in genomic data [5] [6]. | Predicting the number and type of PKS/NRPS clusters in a newly sequenced genome, e.g., Phytohabitans [6]. |

| NaPDoS | Analyzes KS and C domain sequences to predict substrate specificity and phylogeny [6]. | Characterizing the function of KS domains in a novel PKS cluster. | |

| NRPSsp / Norine | Predicts A domain substrate specificity and identifies known nonribosomal peptides, respectively [6]. | Predicting the amino acid sequence of an NRPS product from its gene sequence. | |

| Experimental Materials | CRISPR-Cas9 System | Enables precise gene knockouts or point mutations in vivo [7]. | Inactivating the TE domain of nrps-1 in C. elegans to trap biosynthetic intermediates [7]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) System | Provides an open platform for expressing biosynthetic pathways in vitro [8]. | Rapid prototyping of a PKS pathway without the need for cloning and cultivating a heterologous host. | |

| Sfp Phosphopantetheinyl Transferase | Activates carrier proteins (ACP/PCP) by installing the phosphopantetheine arm; has broad substrate specificity [3]. | Used in vitro to load synthetic aminoacyl-CoAs onto PCP domains to study C domain specificity [3]. | |

| Analytical Instrumentation | High-Resolution LC-MS/MS | Separates, detects, and identifies metabolites and biosynthetic intermediates based on mass and fragmentation [7] [6]. | Identifying the structures of nemamide intermediates accumulated in C. elegans mutant strains [7]. |

The discovery and development of landmark therapeutics derived from natural products represent a triumph of biochemical research and engineering. Among these, artemisinin for malaria and opioid peptides for pain management stand as paradigmatic examples of how elucidating enzymatic pathways can revolutionize medicine. These compounds share a common origin: both are synthesized through complex biosynthetic pathways mediated by specialized enzymes that transform simple precursors into structurally complex, biologically active molecules. The study of these enzymatic mechanisms not only satisfies scientific curiosity but also opens avenues for addressing critical challenges in global health, particularly the sustainable production of essential medicines and the combatting of drug resistance.

Artemisinin, a sesquiterpene lactone from Artemisia annua, and opioid peptides, endogenous neurotransmitters in mammals, exemplify the diversity of nature's biosynthetic capabilities. While their sources and biological functions differ profoundly, the enzymatic principles governing their biosynthesis share remarkable parallels. Both pathways involve precursor modification through sequential enzymatic steps, regulation by multiple enzyme families, and complex spatial organization within producing cells or tissues. Understanding these enzymatic blueprints has enabled synthetic biology approaches to overcome the natural supply limitations of these vital therapeutics, particularly crucial for artemisinin given the persistent global malaria burden described in the 2023 World Malaria Report [9].

This case study examines the enzymatic pathways for artemisinin and opioid biosynthesis through a comparative lens, highlighting both the canonical mechanisms and recent discoveries that have reshaped our understanding. We focus particularly on the experimental approaches that have unraveled these complex pathways and the emerging engineering strategies that promise to revolutionize their production.

Artemisinin Biosynthesis: From Plant to Microbial Production

The Core Enzymatic Pathway

Artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua represents one of the most extensively studied plant natural product pathways, with significant advances occurring in the past decade. The pathway demonstrates sophisticated compartmentalization and regulation, with biosynthesis occurring primarily in the glandular secretory trichomes (GSTs) of the plant [10]. The complete pathway from primary metabolites to artemisinin involves multiple enzymatic steps across different cellular compartments.

Table 1: Key Enzymes in the Artemisinin Biosynthetic Pathway

| Enzyme | Abbreviation | Function | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amorpha-4,11-diene synthase | ADS | Cyclizes FPP to amorpha-4,11-diene | Cytosol |

| Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase | CYP71AV1 | Oxidizes amorpha-4,11-diene to artemisinic alcohol | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase 1 | ADH1 | Oxidizes artemisinic alcohol to artemisinic aldehyde | Cytosol |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 | ALDH1 | Oxidizes artemisinic aldehyde to artemisinic acid | Cytosol |

| Artemisinic aldehyde Δ11(13) double bond reductase | DBR2 | Reduces artemisinic aldehyde to dihydroartemisinic aldehyde | Cytosol |

| Dihydroartemisinic acid dehydrogenase | AaDHAADH | Bidirectional conversion of AA and DHAA | Cytosol |

The upstream pathway begins with the formation of isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) through both the mevalonate (MVA) pathway in the cytosol and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway in plastids [11]. These universal terpenoid precursors condense to form farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), which serves as the direct precursor for artemisinin biosynthesis. The first committed step is catalyzed by amorpha-4,11-diene synthase (ADS), which cyclizes FPP to form amorpha-4,11-diene [11] [12].

The intermediate steps involve oxidation by the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase CYP71AV1, which utilizes molecular oxygen and NADPH to introduce oxygen functionalities, converting amorpha-4,11-diene to artemisinic alcohol [12]. Subsequent oxidation by alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (ADH1) yields artemisinic aldehyde, which represents a key branch point in the pathway. At this juncture, the pathway diverges: aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) can oxidize artemisinic aldehyde to artemisinic acid (AA), while artemisinic aldehyde Δ11(13) double bond reductase (DBR2) reduces the Δ11(13) double bond to form dihydroartemisinic aldehyde (DHAO) [12].

A landmark discovery in 2025 identified dihydroartemisinic acid dehydrogenase (AaDHAADH), which catalyzes the bidirectional conversion between artemisinic acid (AA) and dihydroartemisinic acid (DHAA) [12]. This enzyme provides a crucial link between the two branches of the pathway and represents a significant advance in our understanding of the terminal steps of artemisinin biosynthesis.

The final step from DHAA to artemisinin occurs non-enzymatically through auto-oxidation, likely mediated by reactive oxygen species [12]. However, recent evidence suggests this conversion may be facilitated by specific cellular conditions or potentially undiscovered enzymatic components.

Diagram 1: The complete artemisinin biosynthetic pathway in Artemisia annua, highlighting the recently discovered AaDHAADH enzyme that connects the artemisinic acid and dihydroartemisinic acid branches.

Recent Discoveries and Regulatory Mechanisms

Single-nucleus RNA sequencing studies have revealed that artemisinin biosynthesis is spatially organized within the 10-cell glandular secretory trichomes, with six specific secretory cells serving as the primary production sites [10]. This spatial compartmentalization reflects the complex regulation of the pathway, which involves multiple transcription factors including WRKY, AP2/ERF, bZIP, MYB, and NAC families [13].

Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses have revealed coordinated regulatory mechanisms between artemisinin and flavonoid biosynthesis mediated by transcription factors such as AaMYB8 [9]. This coordination is physiologically significant, as flavonoids have been shown to enhance the antiplasmodial efficacy of artemisinin and delay the development of Plasmodium resistance [9]. The discovery of this synergistic relationship highlights the importance of understanding pathway crosstalk in natural product biosynthesis.

The identification of AaDHAADH represents a fundamental advance in the artemisinin pathway elucidation [12]. Through catalytic activity-guided protein purification combining proteomics and bioinformatics, researchers isolated this enzyme that catalyzes the bidirectional conversion between AA and DHAA. Site-directed mutagenesis yielded an optimized AaDHAADH variant (P26L) with 2.82-fold greater catalytic efficiency than the wild-type enzyme, enabling de novo synthesis of DHAA in engineered S. cerevisiae at titers of 3.97 g/L in a 5L bioreactor [12].

Opioid Peptide Biosynthesis: From Precursors to Active Neurotransmitters

The Canonical Processing Pathway

Opioid peptides represent a fundamentally different class of natural products, synthesized not through terpenoid pathways but via ribosomal translation and post-translational modification. The biosynthesis of endogenous opioid peptides such as enkephalins, endorphins, and dynorphins follows a conserved mechanism for bioactive peptide production in mammalian systems [14].

The pathway begins with the ribosomal synthesis of large protein precursors—proenkephalin, proopiomelanocortin (POMC), and prodynorphin—which contain the active peptide sequences flanked by paired basic amino acid residues [14]. These precursors undergo proteolytic processing in a two-step enzymatic mechanism:

First, a trypsin-like endopeptidase cleaves at the carboxyl terminus of basic amino acids (lysine or arginine), leaving the active peptide with a basic amino acid on its carboxyl terminus [14]. This initial cleavage is followed by the action of carboxypeptidase E (also known as enkephalin convertase), which removes the remaining basic amino acid to yield the mature, biologically active opioid peptide [14].

Table 2: Key Enzymes in Opioid Peptide Biosynthesis

| Enzyme | Function | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Trypsin-like endopeptidase | Cleaves at carboxyl terminus of basic amino acids in precursor proteins | Recognizes paired basic residues (Lys-Arg, Arg-Arg, Lys-Lys, Arg-Lys) |

| Carboxypeptidase E (Enkephalin convertase) | Removes C-terminal basic amino acids to generate mature peptides | Selective for basic residues (Lys, Arg) |

| Peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase | Amidates C-terminal for enhanced stability and activity | C-terminal glycine residues |

This processing pathway exhibits remarkable specificity, with enkephalin convertase showing physiological association with enkephalin biosynthesis and a limited number of other neuropeptides [14]. The enzymatic selectivity in opioid peptide biosynthesis represents a crucial regulatory point, determining the production of specific active peptides from their precursors.

Experimental Approaches in Pathway Elucidation

Methodology for Enzyme Discovery and Characterization

The elucidation of both artemisinin and opioid peptide biosynthetic pathways has relied on sophisticated experimental approaches that have evolved with technological advancements. The recent discovery of AaDHAADH in the artemisinin pathway exemplifies a rigorous, multi-technique approach to enzyme characterization [12].

Catalytic Activity-Guided Protein Purification: Researchers began with crude enzyme extraction from A. annua leaves, confirming catalytic activity capable of converting AA to DHAA [12]. The purification process involved sequential fractionation using:

- 80% ammonium sulfate precipitation

- Dextran G50 gel column chromatography

- Dextran G25 gel column chromatography

- DEAE chromatography

Proteomic Analysis: Active fractions were analyzed by mass spectrometry, identifying 1261 proteins [12]. Bioinformatics filtering narrowed candidates to 61 oxidoreductases, with evolutionary tree analysis revealing three proteins clustering with known artemisinin pathway enzymes.

Heterologous Expression and Functional Validation: Candidate enzymes (AaDHAADH, C90, and V73) were expressed in E. coli and N. benthamiana systems, with only AaDHAADH demonstrating catalytic activity toward AA/DHAA conversion [12].

Enzyme Engineering: Site-directed mutagenesis of AaDHAADH yielded variant P26L with 2.82-fold enhanced activity, enabling high-titer DHAA production in engineered yeast [12].

For opioid peptides, classic biochemical approaches including enzyme inhibition studies and substrate specificity assays revealed the unique selectivity of enkephalin convertase [14]. Modern transcriptomic methods, particularly mRNA quantification and in situ hybridization, now enable dynamic assessment of opioid peptide biosynthesis regulation in response to physiological stimuli [14].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for the discovery and optimization of AaDHAADH, highlighting the multi-step approach from crude enzyme extraction to engineered variant with enhanced activity.

Advanced Omics Technologies in Pathway Analysis

Recent advances in single-cell and spatial omics technologies have revolutionized our ability to resolve complex biosynthetic pathways with cellular precision. In artemisinin research, single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) has overcome previous limitations of cellular heterogeneity in glandular secretory trichomes [10].

Single-Nucleus RNA Sequencing Methodology:

- Mild mechanical extraction of GSTs from 400+ leaves across developmental stages

- Nuclear extraction optimized for GST-enriched and whole-leaf samples

- Droplet-based snRNA-seq with Illumina platform sequencing

- 688 million reads yielding 8,334 leaf nuclei and 7,995 GST-enriched nuclei post-quality control

- Integrated analysis revealing 15 transcriptionally distinct clusters

This approach has precisely mapped artemisinin biosynthesis to six specific secretory cells within the 10-cell GST structure, resolving previous controversies from laser microdissection studies [10]. The integration of spatial transcriptomics has further enabled correlation of metabolic activities with cellular niches, providing unprecedented resolution in understanding the functional specialization of plant secretory structures.

For opioid peptides, modern omics approaches have supplemented classical biochemical studies, enabling researchers to measure dynamic alterations in proenkephalin mRNA levels in response to physiological manipulations such as dopamine receptor blockade [14].

Research Reagent Solutions for Enzymatic Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Natural Product Enzymology

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Expression Systems | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, N. benthamiana | Functional characterization of candidate enzymes and pathway reconstruction |

| Chromatography Media | Dextran G25/G50, DEAE | Enzyme purification and activity-guided fractionation |

| Analytical Standards | Artemisinin, AA, DHAA, opioid peptides | Metabolite quantification and enzyme activity assays |

| Proteomics Kits | Mass spectrometry sample preparation | Identification of proteins in active fractions |

| Cloning Reagents | Site-directed mutagenesis kits | Enzyme engineering and optimization |

| Transcriptomics Reagents | snRNA-seq library prep | Cellular resolution of pathway localization and regulation |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Fosmidomycin (DXR inhibitor) | Pathway flux analysis and rate-limiting step identification |

The enzymatic pathways for artemisinin and opioid biosynthesis, while phylogenetically and chemically distinct, share fundamental principles in natural product biosynthesis. Both involve the transformation of basic precursors through sequential enzymatic steps, regulation by multiple enzyme families, and sophisticated spatial organization within producing cells or tissues. The elucidation of these pathways has enabled advanced bioengineering approaches to address supply limitations, particularly for artemisinin where microbial production of precursors now provides a sustainable alternative to plant extraction.

Recent discoveries such as AaDHAADH in artemisinin biosynthesis [12] highlight that even extensively studied pathways may contain unknown enzymatic steps, underscoring the importance of continued fundamental research. The integration of multi-omics technologies, particularly single-cell and spatial approaches, is revealing unprecedented detail about the cellular organization of natural product biosynthesis [10]. These advances, coupled with protein engineering and synthetic biology, are paving the way for next-generation production systems that will ensure reliable supplies of these essential medicines.

The future of natural product enzymology lies in the deeper integration of computational approaches, including artificial intelligence and deep learning, with experimental validation [15] [16]. As these technologies mature, they will accelerate the discovery and optimization of enzymatic pathways for not only artemisinin and opioids but also the vast repertoire of nature's therapeutic compounds awaiting discovery and exploitation.

The Role of Multifunctional and Heteromeric Enzyme Complexes in Pathway Efficiency

In the intricate landscape of cellular metabolism, organisms have evolved sophisticated enzymatic strategies to optimize the production of specialized compounds. Among these, multifunctional enzymes (MFEs) and heteromeric enzyme complexes represent two pivotal architectural paradigms that significantly enhance biosynthetic pathway efficiency. These systems are particularly crucial in the biosynthesis of natural products, which serve as vital resources for drug discovery and development. This whitepaper examines the mechanisms through which these enzymatic configurations maximize catalytic output, with a specific focus on their roles in secondary metabolic pathways that produce pharmaceutically relevant compounds. By integrating recent case studies and experimental data, we provide a technical guide for researchers aiming to harness these systems for metabolic engineering and drug development.

Fundamental Mechanisms Enhancing Efficiency

Substrate Channeling and Metabolic Compartmentalization

Substrate channeling is a fundamental mechanism through which heteromeric enzyme complexes drastically improve catalytic efficiency. This process enables the direct transfer of reaction intermediates between consecutive active sites without diffusion into the bulk cellular environment [17].

- Equilibrium Bypass: Channeling prevents intermediates from reaching equilibrium in solution, allowing reactions to proceed even when unfavorable equilibrium constants would otherwise limit the process [17].

- Intermediate Protection: Unstable or toxic intermediates are shielded from degradation or side reactions as they are transferred between enzymatic sites [17].

- Concentration Optimization: Local substrate concentrations at active sites are maintained at high levels, significantly increasing reaction rates beyond what would be possible through diffusion-limited processes [17].

Electrostatic potential analysis of mitochondrial complexes like malate dehydrogenase–citrate synthase–aconitase (mMDH–CS–ACON) reveals that enzyme association creates continuous positively charged regions at interfaces, facilitating directed transport of negatively charged intermediates between active sites with minimal cellular diffusion [17].

Proximity Effects and Allosteric Regulation

The spatial organization within multifunctional and heteromeric enzymes enables proximity effects that minimize diffusion distances and transition times between catalytic steps. In multifunctional enzymes, covalent linkage of catalytic domains ensures optimal positioning for intermediate transfer [18]. In heteromeric complexes, specific protein-protein interactions create structured environments that orient catalytic sites for efficient handoff of metabolites.

Additionally, these complexes often exhibit sophisticated allosteric regulation mechanisms. Subunit interactions in heteromeric complexes can induce conformational changes that modulate catalytic activity, substrate specificity, and product profiles, allowing for precise metabolic control that is essential in complex biosynthetic pathways [19].

Table 1: Comparative Features of Multifunctional and Heteromeric Enzyme Systems

| Feature | Multifunctional Enzymes (MFEs) | Heteromeric Enzyme Complexes |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Basis | Single polypeptide chain with multiple catalytic domains | Non-covalent assembly of non-identical subunits |

| Intermediate Transfer | Through covalent linkage between domains | Via substrate channeling between subunits |

| Genetic Encoding | Single gene | Multiple genes |

| Regulatory Flexibility | Coordinated expression of domains | Independent subunit expression and modulation |

| Representative Examples | Type I PKSs, NRPSs [18] | TlxIJ, MbnBC [19] |

Representative Case Studies in Natural Product Biosynthesis

Heteromeric Nonheme Oxygenases in Talaromyolide Biosynthesis

The biosynthesis of talaromyolides, hexacyclic meroterpenoids from the marine fungus Talaromyces purpureogenus, involves a remarkable heteromeric enzyme system. The talaromyolide biosynthetic gene cluster encodes four nonheme iron oxygenases, with TlxI/TlxJ and TlxA/TlxC forming functional heterodimers [19].

Experimental Analysis of TlxI/TlxJ:

- Pull-down assays and electrophoretic mobility shift assays confirmed heterodimer formation [19].

- Size-exclusion chromatography demonstrated stable complex formation in solution [19].

- Crystallographic analysis (PDB ID: 7VBQ) revealed an extensive interface with a buried surface area of 1950 Ų [19].

- Kinetic studies quantified the efficiency enhancement: the TlxI/TlxJ heterodimer exhibited a catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km = 1.63 minâ»Â¹ μMâ»Â¹) approximately 80-fold higher than TlxJ alone (kcat/Km = 0.02 minâ»Â¹ μMâ»Â¹) [19].

This system exemplifies the catalytic complementarity found in heteromeric complexes. While TlxJ contains the complete catalytic apparatus, TlxI provides essential structural elements (particularly loop B') for proper substrate binding and positioning, despite being catalytically incompetent due to the absence of a key arginine residue for α-ketoglutarate binding [19].

Multifunctional Polyketide Synthases in Antibiotic Biosynthesis

6-Methylsalicylic acid synthase (6-MSAS) from Penicillium patulum represents a classic example of a multifunctional enzyme in natural product biosynthesis. This iterative polyketide synthase catalyzes the formation of 6-methylsalicylic acid from one acetyl-CoA and three malonyl-CoA units through successive decarboxylative condensation [18].

Unlike modular PKSs, 6-MSAS reuses its catalytic domains through multiple elongation cycles within a single polypeptide chain containing all necessary catalytic activities [18]. The enzyme lacks a canonical thioesterase (TE) domain for product release, instead employing a specialized thioester hydrolase (TH) activity within its dehydratase (DH) domain to hydrolyze the thioester bond of the tetraketide intermediate [18].

The bacterial homolog ChlB1 from Streptomyces antibioticus, involved in chlorothricin biosynthesis, demonstrates the evolutionary conservation of this multifunctional strategy in diverse organisms [18].

Heterodimeric MbnBC in Methanobactin Biosynthesis

Methanobactins, copper-binding peptides produced by methanotrophic bacteria, are synthesized through the action of the heterodimeric enzyme MbnBC. This complex represents the first biochemically characterized member of the DUF692 protein family and plays a crucial role in posttranslational modifications of the precursor peptide MbnA [19].

Structural and Biophysical Characterization:

- Co-crystal structure (PDB ID: 7FC0) revealed a heterotrimeric MbnABC complex with two extensive interaction interfaces (buried surface area totaling 1772 Ų) [19].

- Mössbauer spectroscopy identified the presence of mixed triferric and diferric clusters within the complex [19].

- Isothermal titration calorimetry measured binding affinities, demonstrating tight binding between MbnA and MbnBC (Kd = 2.7-3.0 μM) that depends critically on both N-terminal leader and C-terminal core peptide regions [19].

In this system, the heterodimeric architecture creates a specialized environment where MbnC acts as a substrate introducer, guiding MbnA to properly position its cysteine residues within the catalytic center of MbnB for oxidation and heterocycle formation [19].

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Protocol for Heteromeric Complex Validation

Objective: Confirm formation and functionality of putative heteromeric enzyme complexes.

Methodology:

- Co-expression and Purification: Clone genes encoding suspected subunits into a single vector for co-expression in E. coli (e.g., pET Duet). Purify using affinity chromatography followed by size-exclusion chromatography [19].

- Interaction Validation:

- Pull-down assays: Immobilize one subunit and test for binding of partner subunit.

- Electrophoretic mobility shift assays: Monitor complex formation via altered migration.

- Size-exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS): Determine native molecular weight and oligomeric state [19].

- Functional Characterization:

- Enzyme kinetics: Compare kcat and Km values for individual subunits versus complexes.

- Stopped-flow spectroscopy: Monitor rapid reaction phases enabled by complex formation.

- Site-directed mutagenesis: Target interfacial residues to disrupt complex formation and assess functional consequences [19].

Protocol for Substrate Channeling Demonstration

Objective: Provide evidence for direct metabolite transfer between enzyme active sites.

Methodology:

- Transient Time Analysis: Measure the lag phase in product formation for coupled reactions using fused enzymes versus free enzyme mixtures; shorter lag times indicate channeling [17].

- Isotope Dilution Experiments: Incubate enzymes with labeled and unlabeled intermediates; reduced dilution of label in final product suggests direct transfer [17].

- Cryo-electron Microscopy: Visualize pathway intermediates trapped within enzyme complexes.

- Computational Electrostatic Analysis: Map surface electrostatic potentials to identify potential charged channels between active sites, as demonstrated for the mMDH-CS-ACON complex [17].

Diagram 1: Substrate channeling mechanism.

Computational and Synthetic Biology Approaches

Deep Learning for Enzyme Kinetics Prediction

The DLKcat deep learning approach enables high-throughput prediction of enzyme turnover numbers (kcat) from substrate structures and protein sequences, addressing a critical bottleneck in metabolic modeling [20].

Model Architecture and Performance:

- Input Representation: Substructures as molecular graphs (from SMILES) and proteins as overlapping 3-gram amino acids [20].

- Neural Network: Graph neural network (GNN) for substrates combined with convolutional neural network (CNN) for proteins [20].

- Prediction Accuracy: Root mean square error of 1.06 on test dataset, with predictions typically within one order of magnitude of experimental values (Pearson's r = 0.88 overall) [20].

- Application Scope: Successfully predicts kcat values for mutated enzymes and identifies critical amino acid residues through attention mechanisms [20].

This approach facilitates the reconstruction of enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs) that more accurately simulate cellular metabolism, proteome allocation, and physiological diversity [20].

Engineering Synthetic Enzyme Complexes

Inspired by natural systems like cellulosomes, synthetic biologists have developed scaffold-based strategies for constructing artificial multi-enzyme complexes [17].

Design Strategies:

- Protein Fusion Technology: Covalently link enzyme domains with flexible peptide linkers to optimize spatial orientation and reduce inter-domain diffusion [17].

- Scaffold-Mediated Assembly: Utilize protein-protein interaction domains (e.g., cohesin-dockerin pairs) to organize enzymes on synthetic scaffolds [17].

- Computational Optimization: Employ molecular dynamics simulations to refine linker lengths and compositions for optimal function [17].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Complex Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Co-expression Systems (pET Duet, pCDF) | Simultaneous expression of multiple subunits | Compatible affinity tags, balanced expression |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography with MALS | Native complex characterization | Determines molecular weight and oligomeric state |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Quantify subunit interactions | Measures binding constants and thermodynamics |

| DLKcat Prediction Tool [20] | kcat value prediction from sequence/structure | Graph neural network + convolutional neural network |

| Alphafold 3 [19] | Protein complex structure prediction | Accurate heterodimer modeling (e.g., TlxA/TlxC) |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The strategic manipulation of multifunctional and heteromeric enzyme systems offers powerful approaches for drug discovery, particularly in optimizing the production of natural product-based therapeutics.

Genome Mining for Novel Natural Products

Understanding the genetic organization and enzymatic logic of multifunctional and heteromeric systems enables targeted genome mining for novel bioactive compounds. For purine-derived N-nucleoside antibiotics like pentostatin, identification of conserved biosynthetic genes (e.g., penA, penB, penC) facilitates the discovery of new producers and structural variants from genomic databases [21].

The protector-protégé strategy observed in pentostatin biosynthesis, where two complementary compounds (pentostatin and vidarabine) are produced from the same cluster, illustrates how heteromeric enzyme organizations can enable synergistic biological activities with therapeutic applications [21].

Metabolic Engineering for Enhanced Production

Heteromeric enzyme complexes provide valuable blueprints for metabolic engineering. The discovery that geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPPS) in tomatoes functions as a heteromeric complex comprising a catalytic large subunit and a non-catalytic small subunit explains why cultivated tomatoes lack monoterpene aromas—due to silencing of the GPPS small subunit gene [22].

This insight directly informs engineering strategies: co-expression of GPPS large and small subunits can enhance GPP production for monoterpene biosynthesis in heterologous hosts, enabling improved production of valuable terpenoid pharmaceuticals [22].

Diagram 2: Heteromeric GPPS engineering strategy.

Multifunctional and heteromeric enzyme complexes represent nature's optimized solution for enhancing metabolic pathway efficiency through spatial organization, substrate channeling, and allosteric coordination. The detailed characterization of these systems—from heteromeric oxygenases in fungal meroterpenoid biosynthesis to multifunctional polyketide synthases in antibiotic production—provides both fundamental insights and practical engineering blueprints. As computational tools like DLKcat prediction and AlphaFold 3 structure modeling continue to advance, our ability to understand, predict, and engineer these complex enzymatic systems will dramatically improve. For drug development professionals, harnessing these architectural principles offers promising strategies for discovering novel natural products, optimizing their production, and ultimately addressing the pressing need for new therapeutic agents.

Divergent evolution is a fundamental evolutionary process whereby species or molecular entities with a common ancestor evolve different traits, often as they adapt to distinct ecological niches or physiological roles [23]. In the context of enzyme evolution and natural product biosynthesis, this process serves as nature's primary engineering strategy for generating remarkable structural diversity from common molecular precursors. This evolutionary mechanism stands in direct contrast to convergent evolution, where structurally distinct, non-homologous enzymes independently evolve the ability to catalyze the same biochemical reaction [24] [25]. Within specialized metabolism, particularly in natural product biosynthesis, divergent evolution operates through the duplication of ancestral genes followed by functional diversification, enabling plants and microorganisms to produce a vast array of specialized metabolites with diverse biological activities [26] [27]. These metabolites play crucial roles in environmental adaptation, defense, and communication, and many have been developed into valuable pharmaceuticals, including the analgesic 3-acetylaconitine and anti-arrhythmic guan-fu base A found in Aconitum species [28].

Understanding the molecular mechanisms driving divergent evolution is particularly valuable for drug development professionals seeking to harness nature's biosynthetic potential. By deciphering how nature engineers chemical diversity, researchers can develop innovative strategies for drug discovery, optimize lead compounds, and access novel chemical space through synthetic biology approaches [28]. This technical guide examines the principles, mechanisms, and experimental methodologies for studying divergent evolution in enzyme systems, with a specific focus on its applications in natural product biosynthesis research.

Molecular Mechanisms of Divergent Evolution

Genetic Foundations: Gene Duplication and Functional Diversification

The primary genetic mechanism underlying divergent evolution in enzyme systems is gene duplication, which provides the raw genetic material for functional innovation. Following duplication, several evolutionary pathways can lead to functional diversity:

- Neofunctionalization: One duplicate copy retains the original function while the other acquires a new beneficial function, potentially through as few as one or two mutations that alter substrate specificity or catalytic mechanism [26] [27].

- Subfunctionalization: Both duplicates undergo complementary degenerative mutations that partition the original functions, leading to specialization [26].

- Escape from Adaptive Conflict: When a single gene is constrained in optimizing multiple functions, duplication allows each copy to specialize in one of these functions [26].

These processes frequently occur through tandem gene duplications, where duplicated genes are arranged in clusters within the genome. A seminal example is the evolution of caffeine and crocin biosynthetic pathways in the Rubiaceae family from a common ancestor that possessed neither complete pathway [27]. In coffee (Coffea canephora), tandem duplication of N-methyltransferase (NMT) genes led to the caffeine biosynthesis pathway, while in gardenia (Gardenia jasminoides), tandem duplication of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CCD) genes gave rise to the crocin biosynthetic pathway [27].

Enzyme Superfamilies: Conservation and Diversification

Enzyme superfamilies represent striking examples of divergent evolution, where members share common structural folds and mechanistic features while catalyzing diverse biochemical reactions. Key structural and mechanistic elements are conserved within superfamilies, particularly those responsible for binding common chemical moieties and stabilizing transition states, while regions governing substrate specificity undergo diversification [25].

Table 1: Characteristic Features of Enzyme Superfamilies Exhibiting Divergent Evolution

| Superfamily | Common Structural Core | Conserved Motifs/Residues | Reaction Diversity | Representative Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP-grasp | ≤4.3 Å Cα r.m.s.d. on ≥230 aa | Two conserved Lys/Arg residues for ATP binding; Mg2+-coordinating residues | Ligase reactions involving acyl-phosphate intermediates | Glutathione synthetase, Biotin carboxylase, Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | ≤3.6 Å Cα r.m.s.d. on ≥220 aa | Metal-binding His and Asp residues; Phosphorylation site (Ser/Thr/fGly) | Phosphatase, sulfatase, phosphodiesterase activities | Alkaline phosphatase, Arylsulfatase, Phosphonoacetate hydrolase |

| Cupin | <4.6 Å Cα r.m.s.d. on >99 aa | Metal-binding His residues; GX5HXHX3,4EX6G motif | Dioxygenase, isomerase, epimerase, lyase activities | Oxalate oxidase, Gentisate 1,2-dioxygenase, Phosphomannose isomerase |

The conservation of the "entatic state" or strained conformation of the active site is particularly noteworthy, as this feature is responsible for substrate binding and transition state stabilization within superfamilies [25]. However, the fate of the transition complex is not necessarily conserved, leading to different reaction outcomes depending on specific enzyme-substrate interactions [25].

Structural and Mechanistic Plasticity in Divergent Evolution

The functional diversification within enzyme superfamilies is enabled by structural plasticity that allows evolution to tinker with enzyme active sites while maintaining structural integrity. This plasticity manifests through:

- Active site remodeling: Modifications to the architecture and physicochemical properties of active site pockets enable accommodation of different substrates [29] [25].

- Mechanistic variation: While core mechanistic features are often conserved, variations in catalytic steps and intermediates lead to different reaction outcomes [29] [24].

- Cofactor divergence: Enzymes derived from common ancestors may evolve to utilize different cofactors or catalytic auxiliaries [24] [28].

A compelling example of such plasticity is found in cytochrome P450 enzymes from Aconitum species, where 14 divergent P450s—eight of them multifunctional—catalyze oxidation at seven different sites of ent-kaurene and ent-atiserene diterpene scaffolds [28]. Protein analysis and mutagenesis experiments have identified key residues that tune P450 activity and product profiles, demonstrating how subtle structural changes can drive functional divergence [28].

Diagram 1: Genetic pathway of divergent evolution showing how gene duplication and subsequent functional specialization create metabolic diversity.

Case Studies in Natural Product Biosynthesis

Caffeine and Crocin Biosynthesis in Rubiaceae

The coffee family (Rubiaceae) provides a exceptional example of divergent evolution within closely related species. Comparative genomic analysis of Coffea canephora (coffee) and Gardenia jasminoides (gardenia) reveals how tandem gene duplications have driven the evolution of distinct specialized metabolic pathways from a common ancestor that possessed neither complete pathway [27].

In coffee, the caffeine biosynthesis pathway evolved through recent tandem duplications of N-methyltransferase (NMT) genes, resulting in a cluster of enzymes that sequentially methylate xanthine precursors to produce caffeine [27]. In gardenia, the crocin biosynthesis pathway emerged through tandem duplication of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CCD) genes, particularly GjCCD4a, which initiates the pathway by cleaving zeaxanthin to produce crocetin dialdehyde [27]. Later steps in the gardenia crocin pathway involve more ancient gene duplications of ALDH and UGT genes, which were presumably recruited into the pathway only after the evolution of the GjCCD4a gene [27].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Divergently Evolved Pathways in Rubiaceae

| Characteristic | Caffeine Pathway in Coffee | Crocin Pathway in Gardenia |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Substrate | Xanthosine | Zeaxanthin |

| Key Duplicated Genes | N-methyltransferase (NMT) | Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CCD) |

| Final Product | Caffeine (purine alkaloid) | Crocins (apocarotenoid pigments) |

| Biological Role | Psychotropic defense compound | Pigment for attraction and possibly defense |

| Key Enzymes | CaMXMT, CaXMT, CaDXMT | GjCCD4a, GjALDH, GjUGT |

| Industrial Application | Stimulant beverages | Food colorant, medicinal compounds |

This case study illustrates how similar genetic mechanisms—tandem gene duplication—can drive the evolution of entirely different metabolic pathways in related species, resulting in divergent evolution of specialized metabolism from common ancestral genetic material [27].

Divergent Multifunctional P450s in Aconitum Diterpenoid Biosynthesis

Aconitum species produce a remarkable diversity of bioactive diterpenoids and diterpene alkaloids, including clinically used compounds such as the analgesic 3-acetylaconitine and anti-arrhythmic guan-fu base A [28]. Recent research has uncovered the enzymatic basis for this chemical diversity through the discovery of 14 divergent cytochrome P450 monooxygenases in Aconitum carmichaelii and Aconitum coreanum, eight of which are multifunctional and catalyze oxidation at seven different sites of ent-kaurene and ent-atiserene scaffolds [28].

These P450s belong to the CYP71, CYP85, and CYP72 clans and exhibit remarkable plasticity in their catalytic activities [28]. Through protein analysis and mutagenesis experiments, researchers have identified key residues that tune P450 activity and product profiles, shedding light on the molecular mechanisms governing functional divergence [28]. The discovery of these P450s has enabled combinatorial biosynthesis of tripterifordin (a bioactive diterpenoid with anti-HIV potential) and 14 novel atiserenoids, some exhibiting allelopathic activity [28].

This case exemplifies how divergent evolution of enzyme families can generate substantial chemical diversity from common scaffolds, providing nature with a versatile toolkit for chemical innovation and adaptation.

Tryptophan Synthase β-Subunit Orthologs

Laboratory evolution studies using OrthoRep, a continuous directed evolution platform, have demonstrated how orthogonal tryptophan synthase β-subunit (TrpB) enzymes can diverge functionally when evolved through multi-mutation pathways in independent replicates [30]. When Thermotoga maritima TrpB (TmTrpB) was evolved under selection pressure only for its primary activity of synthesizing L-tryptophan from indole and L-serine, the resulting sequence-diverse variants spanned a range of substrate profiles useful in industrial biocatalysis [30].

These experiments, which mimicked natural evolutionary processes through depth (many generations) and scale (multiple independent lineages), generated TmTrpB variants with different promiscuous activities toward indole analogs [30]. This study demonstrates that divergent evolution of enzyme orthologs can occur even under selection for a single primary function, as neutral mutations and pleiotropic effects alter promiscuous activities and create functional diversity [30].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Genomic and Transcriptomic Mining for Divergent Enzymes

The identification of divergently evolved enzymes begins with comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic analysis. The following protocol outlines a standard approach for mining divergent enzymes from plant genomes:

RNA Sequencing and Assembly: Perform RNA sequencing of different tissues (leaf, stem, root, flower, fruit) using platforms such as Illumina and Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT). Conduct de novo assembly of transcriptomes using appropriate pipelines (e.g., Canu-SMARTdenovo-3×Pilon) [28] [27].

Gene Family Identification: Use Hidden Markov-based approaches (e.g., hmmsearch) with protein domain profiles (e.g., Pfam databases) to identify candidate enzymes (e.g., TPSs, P450s, methyltransferases) [28] [27].

Phylogenetic Analysis: Construct phylogenetic trees of candidate genes with functionally characterized enzymes to determine evolutionary relationships and identify potential divergent clades [28] [27].

Genomic Context Analysis: Examine genomic neighborhoods of candidate genes to identify tandem duplication events and potential biosynthetic gene clusters [27].

Co-expression Analysis: Identify co-expressed genes that may participate in the same biosynthetic pathway, particularly for enzymes acting on common scaffolds [28].

Functional Characterization of Divergent Enzymes

Once candidate divergent enzymes are identified, their functions must be experimentally validated:

Heterologous Expression: Clone candidate genes into appropriate expression vectors (e.g., pEAQ-HT for plant genes) and express them in suitable host systems such as Nicotiana benthamiana or Saccharomyces cerevisiae [28] [30].

Enzyme Assays: Incubate recombinant enzymes with potential substrates under optimized conditions. For P450s, include necessary redox partners; for transferases, provide appropriate cofactors [28].

Product Analysis: Identify and characterize enzyme products using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and comparison with authentic standards when available [28].

Kinetic Analysis: Determine enzymatic parameters (Km, kcat, specificity constants) for various substrates to quantify catalytic efficiency and substrate preference [30].

Combinatorial Biosynthesis: Combine multiple divergent enzymes in vitro or in engineered microbial hosts to reconstitute biosynthetic pathways and produce novel compounds [28].

Structural and Mechanistic Studies

Understanding the structural basis of functional divergence requires detailed biophysical and biochemical analyses:

Protein Crystallography: Determine three-dimensional structures of divergent enzymes, particularly in complex with substrates or analogs, to identify active site variations [25].

Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Systematically mutate residues in active sites and other regions to identify key determinants of substrate specificity and catalytic activity [28].

Mechanistic Analysis: Use isotope labeling, kinetic isotope effects, and other mechanistic probes to elucidate catalytic mechanisms and identify differences between divergent enzymes [29] [25].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Model enzyme-substrate interactions and conformational dynamics to understand how structural differences translate to functional variation [29].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for identifying and characterizing divergently evolved enzymes, from genomic mining to functional validation.

Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Divergent Evolution

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Divergent Enzyme Evolution

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pEAQ-HT vector | Heterologous expression in N. benthamiana | High-yield protein production for functional characterization [28] |

| Evolution Platforms | OrthoRep continuous evolution system | Laboratory evolution of enzymes | Enables deep evolutionary searches through orthogonal DNA replication [30] |

| Enzyme Assay Components | Cofactors (PLP, NADPH, SAM), substrate libraries | Functional characterization of divergent enzymes | Essential for determining substrate specificity and catalytic mechanisms [28] [30] |

| Analytical Standards | Authentic natural product standards (tripterifordin, crocins, caffeine) | Product identification and quantification | Enables accurate compound identification during pathway elucidation [28] [27] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | M-CSA, CATH, Pfam, COMPASS | Sequence analysis, structural classification, profile-profile comparisons | Identifies evolutionary relationships and functional motifs [29] [31] [25] |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Development

The study of divergent evolution in enzyme systems has profound implications for natural product-based drug discovery and development:

Pathway Elucidation and Engineering: Understanding divergent evolution enables researchers to elucidate biosynthetic pathways of valuable natural products and engineer improved production systems through synthetic biology [28]. For example, the discovery of divergent P450s in Aconitum has opened avenues for producing tripterifordin and novel atiserenoids through combinatorial biosynthesis [28].

Enzyme Engineering for Biocatalysis: Divergent evolution provides natural blueprints for engineering enzymes with altered substrate specificity and novel catalytic activities [30]. Continuous evolution systems like OrthoRep can mimic natural divergent evolution on laboratory timescales, generating enzyme variants with expanded substrate scope for industrial biocatalysis [30].

Drug Lead Diversification: Harnessing the principles of divergent evolution allows medicinal chemists to generate diverse analogs of lead compounds for structure-activity relationship studies and optimization of pharmacological properties [28].

Discovery of Novel Bioactive Compounds: Studying divergent enzyme evolution in medicinal plants can reveal previously unknown biosynthetic pathways and novel bioactive compounds with therapeutic potential [28] [27].

As genomic technologies advance and more biosynthetic pathways are elucidated, the principles of divergent evolution will continue to provide valuable insights and tools for drug development professionals seeking to harness nature's chemical innovation for therapeutic applications.

Harnessing the Toolkit: Modern Strategies for Enzyme Discovery and Pathway Prototyping

AI and Machine Learning for Predictive Enzyme Function and EC Number Annotation

Enzymes are fundamental catalysts in living organisms, responsible for orchestrating the complex metabolic networks that support growth, maintenance, and adaptation [32]. In the specific context of natural product biosynthesis research, enzymes construct the vast chemical diversity of bioactive molecules that have profound implications for drug discovery—over 60% of FDA-approved small molecule drugs are natural products or their derivatives [33]. The Enzyme Commission (EC) number system, developed by the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, provides a hierarchical classification framework that specifies enzyme functions using four digits (e.g., EC 3.1.1.1) [34]. This system enables systematic organization of enzymatic knowledge and facilitates the connection between genetic information and chemical transformations in metabolic pathways.

The exponential growth of genomic data has created a critical bottleneck in enzyme functional annotation. Current estimates indicate that only approximately 50% of proteins discovered in genome projects have reliable functional annotations, with the remainder having unknown, uncertain, or incorrect assignments [35]. This annotation gap is particularly problematic in natural product research, where complete biosynthetic pathways remain unknown for most of the over 300,000 documented natural products [33]. Experimental characterization of enzyme function remains time-consuming and resource-intensive, creating an urgent need for computational approaches that can prioritize candidates for further investigation. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have emerged as transformative technologies for high-throughput enzyme function prediction, enabling researchers to navigate the complex sequence-function landscape of enzymes involved in natural product biosynthesis [32] [36].

Evolution of Computational Approaches for Enzyme Function Prediction

Traditional Methods and Their Limitations

Early computational approaches for enzyme function prediction relied heavily on sequence similarity and homology-based methods. These methods operate under the assumption that enzymes with high sequence similarity tend to share similar functions [37]. Tools such as BLAST leverage this principle by identifying homologous sequences with known functions in databases. The Enzyme Function Initiative-Enzyme Similarity Tool (EFI-EST) further advanced this approach by generating protein sequence similarity networks (SSNs) that visually represent sequence-function relationships within enzyme families [35]. While these methods remain valuable for initial annotations, they suffer from significant limitations, particularly when encountering sequences without significant homologs in databases or when dealing with enzymes that have undergone convergent or divergent evolution [32].

The limitations of traditional methods become apparent in cases where sequence similarity does not reliably predict function. Divergent evolution can result in proteins with different functions sharing high sequence similarity, while convergent evolution can cause proteins with similar functions to exhibit low sequence similarity [32]. These evolutionary complexities create annotation errors that propagate through databases, necessitating more sophisticated approaches that can capture subtle functional patterns beyond sequence alignment.

The Machine Learning Revolution

Machine learning approaches marked a significant advancement by using manually crafted features from protein sequences to predict enzyme function. These features include amino acid composition, physicochemical properties, evolutionary information from position-specific scoring matrices (PSSM), and functional domain annotations [32] [37]. Conventional ML algorithms such as k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Random Forests have been successfully applied to enzyme classification problems [32] [38].

Table 1: Traditional Machine Learning Algorithms for Enzyme Function Prediction

| Algorithm | Key Principles | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) | Instance-based learning; assigns function based on similarity to training examples | Simple implementation; effective for clear sequence-function relationships | Computationally intensive for large datasets; sensitive to irrelevant features |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Finds optimal hyperplane to separate different EC number classes | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; memory efficient | Performance depends on kernel choice; less effective for imbalanced datasets |

| Random Forests | Ensemble method combining multiple decision trees | Robust to noise; handles mixed data types; provides feature importance | Less interpretable than single decision trees; can overfit noisy datasets |

| BRD4 Inhibitor-39 | BRD4 Inhibitor-39, MF:C24H19BrFN9, MW:532.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Anticancer agent 218 | Anticancer agent 218, MF:C23H19F2N3O6, MW:471.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

These traditional ML approaches demonstrated that data-driven methods could successfully predict enzyme functions, but they relied heavily on manual feature engineering, which could introduce human bias and potentially miss important patterns in the raw sequence data [37].

Deep Learning Architectures for EC Number Prediction

Sequence-Based Deep Learning Models

Deep learning has revolutionized enzyme function prediction by enabling end-to-end models that automatically learn relevant features directly from raw protein sequences, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering [32]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can capture conserved motifs and local patterns in protein sequences, while Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their variants model long-range dependencies and contextual information [37].

DEEPre, introduced in 2017, represents an early deep learning framework that combines both convolutional and sequential features from raw enzyme sequences for EC number prediction [37]. This approach automatically handles the feature dimensionality nonuniformity problem—where enzymes of different lengths produce different-sized feature representations—through a robust uniformization method. The system processes both sequence-length-dependent encodings (raw one-hot encoding, PSSM) and sequence-length-independent encodings (functional domains) to generate predictions across the EC number hierarchy.

More recently, transformer-based architectures have demonstrated remarkable performance in enzyme function prediction. DeepECtransformer, developed in 2023, utilizes transformer layers to extract latent features from amino acid sequences and predicts EC numbers for 5,360 different classes, including the recently added EC:7 class (translocases) [39]. The model employs a dual prediction engine: a neural network for direct prediction and a homology search fallback when the neural network provides no prediction. Evaluation studies demonstrated that DeepECtransformer achieved precision values ranging from 0.7589 to 0.9506 across different EC classes, with superior performance compared to both DeepEC and DIAMOND in most metrics [39].

Reaction-Based Classification Approaches

While sequence-based methods predict function from protein sequences, reaction-based approaches classify enzymes according to the chemical transformations they catalyze. BEC-Pred, introduced in 2024, leverages BERT-based transformer architecture trained on reaction SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) representations to predict EC numbers from substrate-product pairs [40].

This approach demonstrates how transfer learning from general organic chemistry reactions can enhance understanding of enzymatic transformations. When trained on both biochemical reactions and natural product-like organic reactions, BEC-Pred achieved a prediction accuracy of 91.6%, outperforming other sequence and graph-based ML methods by 5.5% [40]. The model successfully predicted enzymatic classification for Novozym 435-induced hydrolysis and lipase-catalyzed synthesis, demonstrating its practical utility in natural product biosynthesis research.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Tools for EC Number Prediction

| Tool | Architecture | Input | Coverage | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEEPre [37] | CNN + RNN | Protein sequence | 6 main EC classes | Outperformed previous state-of-the-art methods on large-scale datasets |

| DeepECtransformer [39] | Transformer | Protein sequence | 5,360 EC numbers | Precision: 0.7589-0.9506; Recall: 0.6830-0.9445; F1: 0.6990-0.9469 |

| BEC-Pred [40] | BERT-based Transformer | Reaction SMILES | All EC classes | Accuracy: 91.6%; Superior F1 scores (6.0-6.6% improvement over other methods) |

| CLEAN [40] | Contrastive Learning | Protein sequence | Multiple EC classes | Effective for imbalanced EC number distributions |

Diagram 1: Deep Learning Workflows for EC Number Prediction. This diagram illustrates the parallel approaches of sequence-based and reaction-based deep learning models for enzyme function prediction.

Experimental Validation and Interpretation of AI Predictions

Experimental Validation of Computational Predictions

Robust experimental validation is crucial for establishing the reliability of AI-predicted enzyme functions. In the development of DeepECtransformer, researchers experimentally validated predictions for three previously uncharacterized E. coli proteins (YgfF, YciO, and YjdM) through in vitro enzyme activity assays [39]. The validation protocol typically involves:

- Heterologous Expression: The target gene is cloned into an expression vector and transformed into a suitable host (e.g., E. coli BL21) for protein production.

- Protein Purification: The expressed protein is purified using affinity chromatography (e.g., Ni-NTA resin for His-tagged proteins) followed by buffer exchange to appropriate assay conditions.

- Enzyme Activity Assays: The purified protein is incubated with predicted substrates under optimized conditions, and reaction products are monitored using techniques such as spectrophotometry, mass spectrometry, or HPLC.

- Kinetic Parameter Determination: For confirmed activities, kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) are determined by measuring initial reaction rates at varying substrate concentrations.

Similarly, BEC-Pred was validated against experimentally characterized lipase-catalyzed reactions, correctly predicting EC numbers for Novozym 435-induced hydrolysis and single-step synthesis reactions [40]. These validation approaches bridge computational predictions with experimental biochemistry, building confidence in AI tools for guiding laboratory investigations.

Interpreting AI Decision-Making Processes

A significant advantage of modern deep learning approaches is their increasing interpretability. Techniques such as integrated gradients allow researchers to identify which regions of a protein sequence the model focuses on when making functional predictions [39]. Studies with DeepECtransformer revealed that the model automatically learns to identify functionally important regions, including active site residues and cofactor binding sites, without explicit training on this information [39].

This interpretability is particularly valuable for natural product biosynthesis research, where it can help identify key catalytic residues in uncharacterized enzymes from biosynthetic gene clusters. By understanding the model's reasoning process, researchers can gain biological insights beyond simple functional predictions, potentially identifying structural features that determine substrate specificity or catalytic mechanism.

Applications in Natural Product Biosynthesis Research

Predicting Bioactivity of Natural Products from Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

Machine learning approaches have been successfully applied to predict the bioactivity of natural products directly from biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) sequences. In a 2021 study, researchers trained classifiers to predict antibacterial or antifungal activity based on features extracted from known natural product BGCs [38]. The methodology included:

- Training Set Assembly: Curating BGCs from the MIBiG database with literature-validated bioactivities.

- Feature Extraction: Identifying protein families (PFAM), smCOG annotations, and resistance genes using tools like antiSMASH and Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI).

- Classifier Training: Optimizing random forest, SVM, and logistic regression models using 10-fold cross-validation.

The resulting classifiers achieved accuracies as high as 80% for predicting antibacterial activity and identified specific biosynthetic enzymes associated with antibiotic effects [38]. This approach enables prioritization of BGCs for experimental characterization based on predicted bioactivity, streamlining the discovery of novel therapeutic compounds.

Retro-biosynthetic Pathway Prediction

The elucidation of complete biosynthetic pathways represents a major challenge in natural product research. BioNavi-NP, a deep learning-driven toolkit, addresses this challenge by predicting plausible biosynthetic pathways for natural products using transformer neural networks [33]. The system employs:

- Single-step Retro-biosynthesis: A transformer model trained on biochemical reactions predicts possible precursor molecules for a target natural product.

- Pathway Planning: An AND-OR tree-based planning algorithm iteratively applies single-step predictions to construct multi-step pathways from building blocks.