Engineering Biosynthesis: Synthetic Biology Approaches for Sustainable Magnolol Production

This article comprehensively reviews the application of synthetic biology to address critical challenges in magnolol production.

Engineering Biosynthesis: Synthetic Biology Approaches for Sustainable Magnolol Production

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the application of synthetic biology to address critical challenges in magnolol production. It explores the foundational biosynthesis pathway of magnolol in Magnolia officinalis, detailing the recent identification of the pivotal laccase enzyme MoLAC14. The content covers methodological advances in engineering microbial cell factories and optimizing protein expression for biosynthesis. It further discusses strategies for troubleshooting production bottlenecks, such as enhancing enzyme thermostability and activity through rational design. Finally, the article provides a comparative analysis of synthetic biology-derived magnolol against traditional extraction and chemical synthesis, validating its potential to provide a scalable, sustainable, and high-purity supply of this versatile therapeutic compound for biomedical research and drug development.

Decoding Nature's Blueprint: The Biosynthetic Pathway and Therapeutic Promise of Magnolol

Magnolol (MG), a hydroxylated biphenyl compound derived from the bark of Magnolia officinalis, has garnered significant interest for its broad-spectrum pharmacological activities, including anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective effects [1] [2] [3]. As a natural polyphenol, magnolol exhibits a unique pharmacophore structure consisting of two hydroxylated aromatic rings connected by a single C–C bond, enabling interactions with numerous proteins and contributing to its diverse biological activity [3]. However, its clinical translation faces challenges, primarily due to poor water solubility and low bioavailability [3] [4]. Synthetic biology emerges as a promising approach to overcome these limitations by enabling efficient and sustainable production of magnolol and its semi-synthetic derivatives [5]. This application note delineates the mechanistic underpinnings of magnolol's pharmacological actions, provides detailed experimental protocols for evaluating its efficacy, and explores its therapeutic potential within the context of advanced production platforms.

Anti-Cancer Mechanisms and Quantitative Profiling

Magnolol demonstrates efficacy against a diverse range of cancers by targeting multiple hallmarks of cancer progression. The compound exerts its effects through modulation of critical signaling pathways, induction of programmed cell death, and disruption of metabolic processes.

Table 1: Anti-Cancer Mechanisms of Magnolol Across Various Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Molecular Targets & Mechanisms | Experimental Models | Key Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) | Inhibits EGFR/NF-κB axis; induces caspase-3, -8, -9 cleavage; promotes M1 macrophages & dendritic cells [6]. | MOC1-bearing animal models [6]. | Tumor growth suppression; increased activated cytotoxic T cells; reduced phosphorylation of EGFR/NF-κB [6]. |

| Multiple Cancers (e.g., Bladder, Colon, Liver, Lung) | Modulates NF-κB, MAPK, PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways; induces apoptosis & autophagy; inhibits DNA synthesis [1] [3]. | Various cell lines & animal models [1] [3]. | Effective against numerous cancer types; induces apoptosis in liver & colon cancer cells; promotes autophagy in lung cancer cells [1] [3]. |

| Gallbladder Cancer | Suppresses cancer cell growth via p53 pathway [3]. | Cell line studies [3]. | Growth inhibition via p53-mediated mechanisms [3]. |

| Via Mitochondrial Targeting | Disrupts mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC); increases ROS; induces mitophagy & apoptosis [7] [4]. | C. elegans; A. suum larvae; various tumor cells [7] [4]. | EC₅₀ vs. A. suum: 11.08 μM [7]; Derivative MTP showed enhanced cytotoxicity vs. parent MAG [4]. |

The following diagram illustrates the core anti-cancer signaling pathways modulated by magnolol and its derivatives:

Synthetic Biology and Biosynthesis Protocols

The sustainable production of magnolol is critical for ongoing research and therapeutic development. Traditional extraction from Magnolia officinalis bark is constrained by low yields (approximately 1-10%) and a long cultivation cycle of 10-15 years [5] [3]. Chemical synthesis often suffers from low yield, lack of specificity, and environmental concerns [5]. Synthetic biology offers a viable alternative.

Proposed Biosynthetic Pathway and Key Enzyme Identification

Research has proposed a biosynthetic pathway where magnolol is synthesized from chavicol, a precursor derived from tyrosine. The conversion is catalyzed by a key enzyme, laccase (MoLAC14) [5].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Magnolol Biosynthesis and Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MoLAC14 (Laccase Enzyme) | Catalyzes the oxidative coupling of two chavicol molecules into magnolol [5]. | Key identified enzyme from M. officinalis; can be engineered for improved stability (e.g., E345P, G377P, L532A mutations) [5]. |

| pET-28a Vector | Expression vector for heterologous production of laccase enzymes in microbial systems [5]. | Used for cloning and expressing MoLAC14 and other candidate laccase genes [5]. |

| Chavicol | Direct precursor substrate for magnolol synthesis in the proposed enzymatic pathway [5]. | Proposed to be synthesized from tyrosine via enzymes like TAL, 4CL, CCR, and ADH [5]. |

| HPLC with PDA Detector | Analysis and quantification of magnolol produced in enzymatic reactions or extracted from samples [5] [7]. | Used for high-resolution antiparasitic profiling and validating magnolol synthesis [7]. |

| S. cerevisiae or E. coli | Model host organisms for the heterologous production of magnolol using synthetic biology approaches [5]. | Engineered microbial chassis for biosynthetic production. |

Protocol: In Vitro Enzymatic Synthesis of Magnolol

This protocol outlines the key steps for producing magnolol using the identified laccase enzyme, MoLAC14 [5].

- Objective: To catalyze the conversion of chavicol into magnolol using recombinantly expressed MoLAC14 laccase.

Materials:

- Cloned Vector: pET-28a vector containing the codon-optimized MoLAC14 gene (or mutant variants like L532A for higher yield).

- Expression Host: E. coli BL21(DE3) competent cells.

- Culture Media: LB broth supplemented with appropriate antibiotic (e.g., Kanamycin, 50 µg/mL).

- Inducer: Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG).

- Substrate: Chavicol.

- Buffers: Lysis buffer (e.g., PBS or Tris-HCl with lysozyme), purification buffers (if performing protein purification via His-tag).

- Analysis Equipment: HPLC system with a C18 column and PDA detector.

Procedure:

- Heterologous Expression: Transform the pET-28a-MoLAC14 plasmid into E. coli BL21(DE3). Grow the culture in LB medium at 37°C until OD₆₀₀ reaches ~0.6. Induce protein expression by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 0.1-0.5 mM and incubate further at a lower temperature (e.g., 16-18°C) for 16-20 hours.

- Enzyme Preparation: Harvest cells by centrifugation. Lyse the cell pellet using sonication or lysis buffer. The crude lysate containing the enzyme can be used directly, or the enzyme can be purified using affinity chromatography (if a His-tag is present).

- Enzymatic Reaction: Set up a reaction mixture containing:

- Buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, 50-100 mM, pH ~7.0)

- Chavicol substrate (concentration to be optimized, e.g., 1-10 mM)

- Enzyme preparation (crude lysate or purified protein)

- Incubate at 30-37°C with shaking for several hours.

- Reaction Termination & Analysis: Stop the reaction by adding an equal volume of methanol or acetonitrile. Remove precipitates by centrifugation. Analyze the supernatant using HPLC.

- HPLC Conditions (example): C18 column; mobile phase: gradient of water (with 0.1% formic acid) and acetonitrile (with 0.1% formic acid); flow rate: 0.5-1.0 mL/min; detection: UV at 254-290 nm. Compare the retention time and spectrum with a magnolol standard.

- Validation: Confirm magnolol identity using Mass Spectrometry (MS) by comparing the mass-to-charge ratio with the standard.

Notes: The mutant MoLAC14 (L532A) has been reported to significantly enhance magnolol production, reaching levels up to 148.83 mg/L in vitro [5].

The workflow for magnolol production and validation, from gene identification to final analysis, is depicted below:

Experimental Protocols for Therapeutic Efficacy Evaluation

Protocol: Evaluating Magnolol as a Radiosensitizer in Oral Cancer Models

This protocol describes the in vivo evaluation of magnolol's efficacy in enhancing radiotherapy for oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) [6].

- Objective: To assess the combined effect of magnolol and radiation therapy (RT) on tumor growth, apoptosis, and immune modulation in a murine OSCC model.

Materials:

- Animals: 6-8 week-old male C57BL/6 mice.

- Cell Line: MOC1 OSCC cells.

- Reagents: Magnolol (for gavage), Erlotinib (positive control), DMSO, Matrigel, Isoflurane/anesthetic cocktail (Zoletil 50/Xylazine).

- Equipment: Linear accelerator for radiotherapy, Flow cytometer, Equipment for immunohistochemistry (IHC).

- Antibodies: For flow cytometry (e.g., CD8, IFN-γ, IL-2, CD11b, CD11c, Ly-6G/Ly-6C) and IHC (e.g., Cleaved Caspase-3, -8, -9) [6].

Procedure:

- Tumor Inoculation: Harvest and resuspend MOC1 cells in a 3:7 mixture of culture medium and Matrigel. Subcutaneously inject 1 x 10ⶠcells in a 100 µL volume into the right cheek of each anesthetized mouse.

- Group Allocation and Treatment: When the average tumor volume reaches ~60 mm³, randomize mice into five groups (n=5/group):

- Group 1 (Control): Daily gavage with vehicle (0.1% DMSO in water).

- Group 2 (Magnolol alone): Daily gavage with magnolol (40 mg/kg/day).

- Group 3 (RT alone): Single dose of 6 Gy radiation to the tumor site on day 1.

- Group 4 (Magnolol + RT): Daily gavage with magnolol (40 mg/kg/day) starting on day 0, plus a single dose of 6 Gy on day 1.

- Group 5 (Erlotinib + RT): Daily gavage with erlotinib (20 mg/kg/day) starting on day 0, plus a single dose of 6 Gy on day 1.

- Monitoring: Measure tumor dimensions bi-daily using callipers. Calculate volume as (Height × Width² × 0.523). Monitor animal body weight as an indicator of general health and toxicity.

- Terminal Analysis: On day 24, euthanize mice and collect samples:

- Tumors: Weigh and record. Divide for IHC (fixed in formalin) and flow cytometry (single-cell suspension for immune profiling).

- Spleen and Lymph Nodes: Process into single-cell suspensions for flow cytometry.

- Immune Profiling by Flow Cytometry: Stain cells with specific antibody panels.

- Cytotoxic T cells: Surface stain for CD8, intracellular stain for IFN-γ and IL-2 after stimulation.

- Macrophages/Dendritic Cells: Surface stain for M1 (e.g., CD11c, CD86) and M2 (e.g., CD206) markers.

- Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) & Tregs: Stain for CD11b, Ly-6G/Ly-6C, and FoxP3.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Perform IHC on tumor sections for cleaved caspase-3, -8, and -9 to assess apoptosis, and for phospho-EGFR and phospho-NF-κB to evaluate pathway inhibition.

Key Outcome Measures:

- Tumor growth curves and final tumor weight.

- Flow cytometry data on immune cell populations within the tumor microenvironment (TME).

- IHC scoring for apoptosis markers and signaling pathway activation.

Protocol: Antiparasitic Screening Assay for Magnolol

This protocol details an in vitro assay to evaluate the anthelmintic (anti-parasitic worm) efficacy of magnolol [7].

- Objective: To determine the efficacy (ECâ‚…â‚€) of magnolol against the larval stage of the porcine roundworm Ascaris suum, a model parasite.

Materials:

- Parasite Material: Fresh Ascaris suum adults from a slaughterhouse. Embryonated eggs are isolated and hatched to obtain larvae.

- Reagents: Magnolol (dissolved in DMSO), Ivermectin (positive control), Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), RPMI-1640 Medium, Penicillin-Streptomycin, Amphotericin B.

- Equipment: COâ‚‚ incubator, Sonicated water bath, Baermann apparatus, 96-well plates, Inverted microscope.

Procedure:

- Larval Preparation: Isolate eggs from female A. suum worms and embryonate them. Hatch the embryonated eggs in HBSS with antibiotics at 37°C and 5% CO₂ to obtain L3 larvae. Separate larvae using a Baermann apparatus and collect active larvae.

- Assay Setup: Transfer approximately 50 live, motile larvae per well into a 96-well plate containing RPMI-1640 medium.

- Compound Treatment: Add magnolol (in DMSO, final DMSO concentration ≤1%) to the wells across a range of concentrations (e.g., 1-100 µM). Include a negative control (vehicle only) and a positive control (Ivermectin).

- Incubation and Assessment: Incubate the plate at 37°C and 5% CO₂ for 24 hours. After incubation, count the number of live larvae (defined as those exhibiting movement within 4 seconds of observation) in each well under a microscope.

- Data Calculation: Calculate larval mortality for each concentration using the formula:

Mortality (%) = [1 - (Live larvae 24h after treatment / Live larvae before treatment)] × 100% - Dose-Response Analysis: Plot mortality (%) against the log of compound concentration and calculate the EC₅₀ value using non-linear regression.

Notes: This assay confirmed magnolol's anthelmintic effect with an EC₅₀ of 11.08 µM, primarily through inhibition of the mitochondrial electron transport chain [7].

Magnolol represents a multifaceted therapeutic agent with demonstrated efficacy in oncology, immunology, and parasitology. Its ability to target critical pathways like EGFR/NF-κB, induce mitochondrial dysfunction, and modulate the immune response underscores its significant potential [1] [6] [7]. However, inherent limitations of the native compound, such as poor solubility and bioavailability, necessitate advanced strategies. The development of semi-synthetic derivatives, particularly mitochondrion-targeted compounds like MTP, and the application of synthetic biology for its biosynthesis are promising avenues to enhance its therapeutic index and enable scalable production [5] [3] [4]. Future research should focus on advancing these derivatives through preclinical and clinical trials, further optimizing synthetic biology platforms for high-yield magnolol production, and exploring its synergistic potential with existing therapies across a broader range of diseases.

Magnolol, a bioactive lignan found primarily in the bark of Magnolia officinalis, has garnered significant scientific interest due to its diverse pharmacological properties, including antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer activities [8] [9]. The growing demand for magnolol in pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications is severely constrained by the limitations of its traditional sourcing methods. This application note details these critical bottlenecks and provides the research community with established protocols for quantifying the challenges and exploring synthetic biology solutions.

Quantitative Analysis of Traditional Sourcing Limitations

The constraints of conventional magnolol production can be summarized through the following key data points, which highlight the inefficiency and unsustainability of current practices.

Table 1: Key Limitations in Traditional Magnolol Production

| Limitation Factor | Quantitative Metric | Impact and Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cultivation Time [5] | 10 to 15 years | The lengthy growth period required for Magnolia officinalis trees before bark harvest creates a significant supply bottleneck and impedes rapid response to market demands. |

| Final Product Concentration [5] | ~1% (in dry bark) | The low concentration of magnolol in the plant material makes extraction processes inherently inefficient and resource-intensive. |

| Chemical Synthesis Challenge [5] | Low yield, multiple by-products | Traditional chemical synthesis routes are hampered by non-specific reactions, leading to poor yields and generation of undesirable by-products, complicating purification. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation and Analysis

To empirically characterize these limitations and advance alternative production platforms, the following laboratory protocols are essential.

Protocol: Quantification of Magnolol in Plant Material via HPLC

Objective: To accurately determine the concentration of magnolol in dried bark of Magnolia officinalis. Background: This protocol validates the low yield of magnolol from its natural source, providing a baseline for evaluating alternative production methods [5].

Materials & Reagents:

- Dried, powdered bark of Magnolia officinalis

- HPLC-grade methanol, acetonitrile, and purified water

- Analytical standard of magnolol (purity >98%)

- Ultrasonic water bath

- Vacuum filtration setup

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system with a UV detector

Procedure:

- Extraction: Precisely weigh 1.0 g of powdered bark. Add 10 mL of methanol and sonicate in a water bath for 60 minutes at 40°C.

- Filtration: Centrifuge the extract and filter the supernatant through a 0.45 μm membrane filter.

- HPLC Analysis:

- Column: C18 column (e.g., 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 3 μm)

- Mobile Phase: Utilize a gradient of solvent A (water with 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid).

- Gradient Program: 0 min: 50% B; 10 min: 80% B; 15 min: 100% B; hold for 5 min.

- Flow Rate: 0.8 mL/min

- Detection: UV absorbance at 290 nm

- Injection Volume: 10 μL

- Quantification: Generate a calibration curve using the magnolol standard at concentrations of 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL. Calculate the magnolol concentration in the bark sample from the curve.

Protocol: In Vitro Biosynthesis of Magnolol Using Recombinant Laccase

Objective: To demonstrate the one-step enzymatic conversion of chavicol to magnolol, establishing a foundational reaction for synthetic biology approaches [5]. Background: This protocol outlines a key reaction for a potential synthetic biology route to magnolol, bypassing the need for plant cultivation.

Materials & Reagents:

- Recombinant MoLAC14 laccase (or other functional ortholog)

- Chavicol substrate

- Sodium acetate buffer (100 mM, pH 5.0)

- Orbital shaker incubator

- HPLC system (as in Protocol 3.1)

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube, combine 970 μL of sodium acetate buffer, 20 μL of a 50 mM chavicol stock solution (in DMSO, final concentration 1 mM), and 10 μL of purified MoLAC14 laccase.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture in an orbital shaker at 30°C and 200 rpm for 4 hours.

- Reaction Termination: Stop the reaction by adding 1 mL of ice-cold methanol.

- Analysis: Centrifuge the mixture and analyze the supernatant by HPLC using the method described in Protocol 3.1 to detect and quantify the formation of magnolol.

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

The logical and experimental workflow for addressing the sourcing limitations is summarized in the following diagrams.

Diagram 1: R&D strategy for magnolol production.

The proposed biosynthetic pathway for magnolol in Magnolia officinalis, which serves as the blueprint for synthetic biology efforts, is as follows:

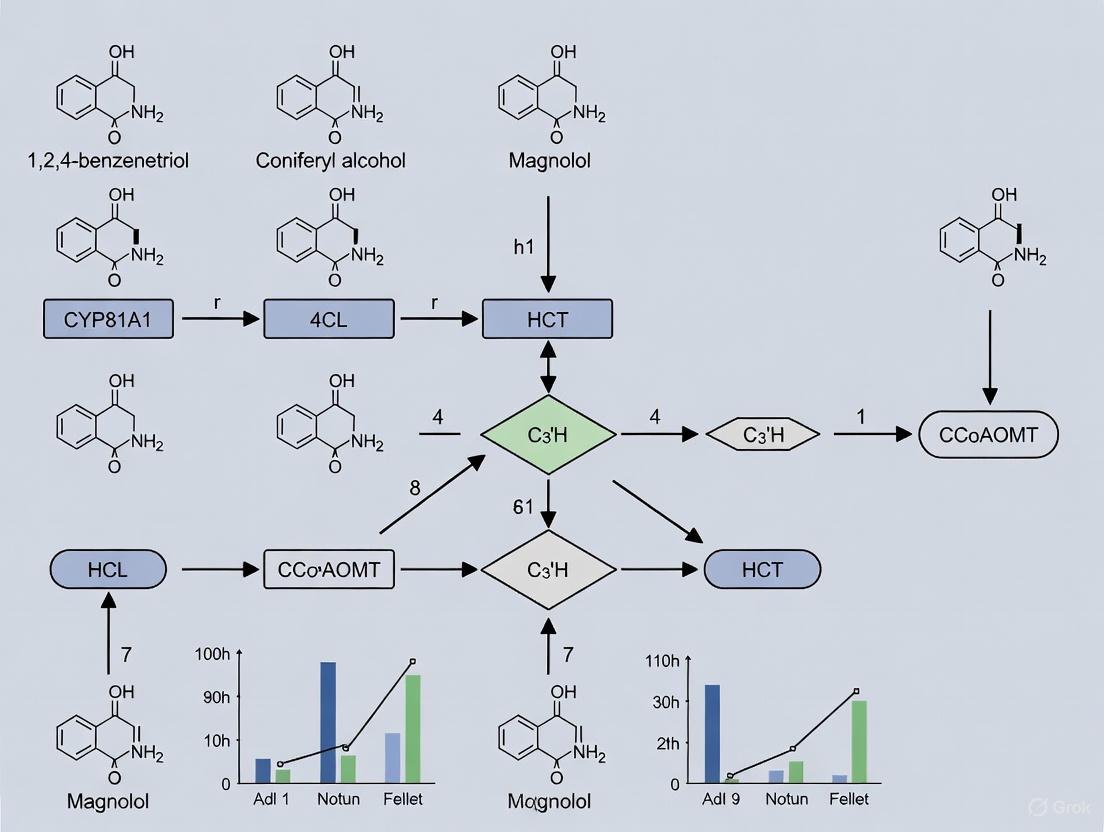

Diagram 2: Proposed magnolol biosynthetic pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Magnolol Biosynthesis Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Laccase MoLAC14 [5] | Key enzyme catalyzing the dimerization of chavicol to form magnolol. | Critical for synthetic biology routes. Engineered variants (e.g., E345P, L532A) show improved thermal stability and activity. |

| Chavicol [5] | Direct precursor substrate for magnolol synthesis in the proposed enzymatic pathway. | Serves as the starting material for the one-step in vitro biosynthesis of magnolol using laccase. |

| Magnolol Standard | Essential analytical standard for quantification and method calibration. | Used in HPLC analysis (e.g., Protocol 3.1) to identify and quantify magnolol in extracts or biosynthesis reaction mixtures. |

| HPLC System with C18 Column | Core analytical platform for separation, identification, and quantification of magnolol and related compounds. | Enables quality control and yield determination for both traditional extraction and novel synthesis methods. |

| 14,15-Leukotriene A4 Methyl Ester | 14,15-Leukotriene A4 Methyl Ester, MF:C21H32O3, MW:332.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| G-quadruplex ligand 1 | G-quadruplex ligand 1, MF:C40H50N8O3, MW:690.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Within the framework of synthetic biology approaches for the production of the valuable natural product magnolol, elucidating its native biosynthetic pathway in Magnolia officinalis is a fundamental prerequisite. Magnolol, a hydroxylated biphenyl compound with potent antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer properties, is traditionally extracted from the bark of Magnolia officinalis [8] [3]. However, direct plant extraction faces significant challenges due to the long cultivation time required (10–15 years) and the low concentration of magnolol in the plant (approximately 1%) [10]. Synthetic biology offers a promising alternative for the sustainable manufacturing of magnolol, but this requires a complete understanding of its biosynthetic genes and enzymes [10] [11]. For decades, the plant-based biosynthesis of magnolol remained obscure [10]. While it was speculated to stem from the common lignan biosynthesis pathway, recent research has identified a more direct route involving the coupling of two chavicol molecules [10] [12]. This application note details the identification and validation of the one-step conversion of chavicol to magnolol, catalyzed by a specific laccase enzyme, MoLAC14, and outlines experimental protocols for its study and optimization [10].

The Chavicol-to-Magnolol Biosynthetic Pathway

Pathway Hypothesis and Key Enzymes

The proposed biosynthetic pathway for magnolol begins with the amino acid tyrosine. Through a series of enzymatic steps involving tyrosine ammonia-lyase (TAL), 4-coumarate CoA ligase (4CL), cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), tyrosine is converted to p-coumaryl alcohol [10]. Subsequent action by coniferyl alcohol acetyltransferase (CAAT) and allylphenol synthases (APS) yields the immediate precursor, chavicol [10]. The critical, one-step conversion of magnolol from chavicol is hypothesized to be catalyzed by an oxidative enzyme, laccase [10]. Laccases oxidize phenolic substrates, generating dimeric products through the coupling of radical intermediates. In this case, the oxidative coupling of two chavicol molecules forms the magnolol biphenyl structure [10] [12].

Identification of the Key Laccase Gene, MoLAC14

To validate this hypothesized pathway, a comprehensive transcriptome analysis of various tissues from Magnolia officinalis was conducted [10]. This effort identified 30 potential laccase genes in the M. officinalis genome. Gene expression analysis revealed high expression of specific laccases in roots, leaves, and bark tissues. Two gene clusters, MoLAC4 and MoLAC17, were identified as potential contributors to magnolol biosynthesis [10]. From these clusters and other highly expressed genes, six candidate laccase genes (MoSKU5F, MoLAC7B, MoLAC14, MoLAC4A, MoLAC4B, and MoLAC17F) were selected for functional characterization [10]. In vitro enzymatic assays confirmed that MoLAC14 is the pivotal enzyme responsible for the conversion of chavicol into magnolol [10].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Assay for Laccase Activity and Magnolol Production

Objective

To express and purify candidate laccase enzymes and test their ability to catalyze the conversion of chavicol to magnolol in a controlled in vitro system [10].

Materials and Reagents

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Laccase Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| pET-28a Vector | Expression vector for cloning and expressing laccase genes in E. coli. | Standard laboratory supplier |

| BL21(DE3) E. coli | Bacterial strain for protein expression. | Standard laboratory supplier |

| Chavicol | The enzymatic substrate, precursor to magnolol. | Chemical supplier (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich) |

| Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) | Chemical inducer for gene expression. | Standard laboratory supplier |

| Copper (II) ions (Cu²âº) | Essential cofactor for laccase enzyme activity. | Standard laboratory supplier |

Procedure

- Gene Cloning and Expression:

- The coding sequences (CDS) of the candidate laccase genes (e.g., MoLAC14) are cloned into the pET-28a expression vector between the Nde I and Xho I restriction sites [10].

- The constructed plasmids are transformed into the BL21(DE3) E. coli expression strain [10].

- The transformed strain is cultured in a suitable medium (e.g., LB broth) at 37°C until the optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) reaches approximately 0.6 [10].

- Gene expression is induced by adding IPTG. Concurrently, Copper (II) ions (Cu²âº) are added to the culture to ensure proper folding and activity of the laccase enzyme [10].

- The culture is incubated further to allow protein production.

- Enzyme Preparation:

- Cells are harvested by centrifugation and lysed to release the soluble proteins.

- The recombinant laccase enzyme can be used in crude lysate or purified via affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag purification) for more precise assays [10].

- In Vitro Enzymatic Reaction:

- The reaction mixture is set up containing the purified laccase enzyme and the substrate, chavicol, in an appropriate buffer [10].

- The reaction is incubated at a defined temperature and pH optimal for laccase activity.

- The reaction is stopped at various time points by heat inactivation or acidification.

- Product Analysis:

- The reaction products are analyzed using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Mass Spectrometry (MS) [10].

- The formation of magnolol is confirmed by comparing its retention time and mass spectrum with an authentic standard.

Protocol 2: Protein Engineering to Enhance MoLAC14 Performance

Objective

To improve the thermal stability and catalytic activity of MoLAC14 through site-directed mutagenesis for more efficient magnolol production [10].

Procedure

- Mutagenesis Design:

- Based on structural analysis or sequence alignment with stable laccases, target specific amino acid residues for mutation.

- To enhance thermal stability, introduce proline residues (e.g., E345P, G377P) to rigidify flexible loops, or engineer additional disulfide bonds (e.g., E346C) [10].

- To probe and improve activity, perform alanine scanning mutagenesis to identify essential residues. Subsequently, target non-essential residues for beneficial mutations (e.g., L532A) [10].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis:

- Introduce the desired mutations into the MoLAC14 gene in the pET-28a plasmid using a commercial mutagenesis kit or overlap extension PCR.

- Expression and Purification:

- Express and purify the mutant enzymes following the same protocol as for the wild-type enzyme (Protocol 1, steps 1-2).

- Characterization of Mutants:

- Thermal Stability Assay: Incubate wild-type and mutant enzymes at elevated temperatures for a set duration. Measure the residual activity using a standard laccase substrate (e.g., ABTS) or chavicol. Calculate the half-life or melting temperature (Tₘ) [10].

- Enzymatic Activity Assay: Measure the initial reaction rates of wild-type and mutant enzymes with chavicol as a substrate under identical conditions. Quantify magnolol production via HPLC to determine the specific activity [10].

Key Experimental Data and Findings

Validation of MoLAC14 Activity

In vitro experiments confirmed that MoLAC14 successfully catalyzes the formation of magnolol from chavicol. The product was unequivocally identified by HPLC and MS analysis, establishing MoLAC14 as the key biosynthetic enzyme in the native pathway [10].

Performance of MoLAC14 Mutants

Protein engineering led to significant improvements in the enzyme's properties. The table below summarizes the effects of key mutations on thermal stability and magnolol production yield [10].

Table 2: Effects of MoLAC14 Mutations on Enzyme Performance

| Mutation | Type of Modification | Effect on Enzyme | Impact on Magnolol Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| E345P, G377P | Introduction of proline | Enhanced thermal stability | Not Specified |

| H347F, E346F | Aromatic substitution | Enhanced thermal stability | Not Specified |

| E346C | Potential disulfide bond | Enhanced thermal stability | Not Specified |

| L532A | Alanine scan mutation | Likely enhanced catalytic activity | Boosted production to 148.83 mg/L |

The identification of MoLAC14 as the laccase catalyzing the direct conversion of chavicol to magnolol represents a critical breakthrough in elucidating the native biosynthetic route of this valuable compound [10]. Furthermore, the successful engineering of MoLAC14 to enhance its stability and the subsequent dramatic increase in magnolol titer to 148.83 mg/L demonstrates the power of enzyme optimization for metabolic engineering [10]. These findings provide the essential genetic and enzymatic foundation for the synthetic biology-driven production of magnolol. The genes encoding the enzymes from tyrosine to chavicol, combined with the optimized MoLAC14 gene, can now be assembled into a microbial chassis (e.g., E. coli or yeast) to create a cell factory for the sustainable and efficient production of magnolol, overcoming the limitations associated with traditional plant extraction [10].

Within the framework of synthetic biology for the production of magnolol, a plant-derived compound with potent antibacterial properties, the identification and engineering of key biosynthetic enzymes is a fundamental research objective [10] [11]. Traditional extraction of magnolol from the bark of Magnolia officinalis is inefficient, requiring 10–15 years of tree cultivation and yielding low concentrations of the target compound (approximately 1%) [10]. Synthetic biology offers a promising alternative, but its application has been hampered by a lack of understanding of the magnolol biosynthesis pathway in the plant [10]. Recent research has identified a one-step conversion of the precursor chavicol into magnolol, catalyzed by laccase enzymes, with the laccase MoLAC14 from M. officinalis emerging as a pivotal biocatalyst [10] [11]. This application note details the functional identification and validation protocols for MoLAC14, providing a methodological foundation for leveraging this enzyme in synthetic microbial factories for magnolol production.

Laccase Structure and Catalytic Mechanism in Magnolol Synthesis

Laccases (EC 1.10.3.2) are multi-copper oxidases that catalyze the one-electron oxidation of a broad range of substrates, including phenolics, with the concomitant four-electron reduction of molecular oxygen to water [13] [14]. This makes them ideal green catalysts for synthetic biology, as they operate without the need for cofactors and produce water as the only by-product [14] [15].

The catalytic center of laccase contains four copper atoms, classified into three types: a Type 1 (T1) copper, which is responsible for the enzyme's characteristic blue color and is the primary site for substrate oxidation; a Type 2 (T2) copper; and a binuclear Type 3 (T3) copper cluster [13] [15]. The T2 and T3 coppers form a trinuclear cluster (TNC) where the reduction of oxygen occurs. The proposed mechanism for magnolol synthesis involves the oxidation of two chavicol molecules by the T1 copper. The electrons removed from the substrates are transferred internally via a conserved His-Cys-His tripeptide bridge to the trinuclear cluster, where oxygen is reduced to water. The oxidized chavicol molecules form radicals that subsequently couple to form magnolol [10] [14]. The following diagram illustrates this catalytic process and its integration into the experimental workflow for identifying functional laccases.

Identification and Validation of MoLAC14

Transcriptome Analysis and Candidate Gene Selection

The identification of MoLAC14 began with a comprehensive transcriptomic analysis of various tissues from M. officinalis [10]. This involved:

- RNA Sequencing: Transcriptome sequencing of 20 samples from different tissues (e.g., bark, leaves, roots) of 16-year-old M. officinalis plants.

- Genome Annotation Enhancement: Assembled RNA-seq reads were mapped to the existing M. officinalis genome, significantly enriching its annotation and leading to the identification of 30 distinct laccase genes [10].

- Candidate Selection: Two potential laccase gene clusters (MoLAC4 and MoLAC17) associated with magnolol production were identified. Six highly expressed laccase genes from these clusters and other magnolol-producing tissues (including MoSKU5F, MoLAC7B, MoLAC14, MoLAC4A, MoLAC4B, and MoLAC17F) were selected for functional characterization [10].

Experimental Protocol: Cloning, Expression, and In Vitro Assay

The following protocol details the key steps for the heterologous expression and functional testing of candidate laccases like MoLAC14.

Protocol 1: Functional Testing of Recombinant Laccase Activity

- Objective: To heterologously express candidate laccase genes and test their ability to catalyze the conversion of chavicol to magnolol in vitro.

- Principle: The coding sequence (CDS) of the laccase gene is cloned into an expression vector, transformed into E. coli, and the expressed enzyme is used in a reaction with chavicol. The formation of magnolol is confirmed using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Mass Spectrometry (MS) [10].

Materials and Methods:

- Gene Synthesis and Cloning:

- The CDS of the selected laccase genes are synthesized and integrated into a pET-28a vector between the Nde I and Xho I restriction sites using Gibson assembly [10].

- Heterologous Expression:

- The constructed plasmids are chemically transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) expression strain.

- The transformed strain is cultured in LB medium at 37°C.

- Gene expression is induced by adding Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG).

- Concurrently, Copper (II) ions (Cu²âº) are added to the culture to facilitate the proper assembly of the laccase's multi-copper center [10].

- In Vitro Activity Assay:

- The expressed laccase is purified or used in a crude cell lysate.

- The enzyme is incubated with the substrate chavicol in a suitable reaction buffer.

- Product Detection and Validation:

- The reaction mixture is analyzed using HPLC to separate and quantify the products.

- The identity of magnolol is confirmed by Mass Spectrometry (MS) by comparing its mass and fragmentation pattern to an authentic standard [10].

Results and Validation: In vitro experiments confirmed that MoLAC14 could efficiently catalyze the one-step conversion of chavicol to magnolol. HPLC and MS analyses provided definitive evidence of magnolol production, identifying MoLAC14 as a pivotal enzyme in the magnolol biosynthetic pathway [10] [11].

Engineering MoLAC14 for Enhanced Performance

Protein engineering was employed to enhance the thermal stability and catalytic efficiency of MoLAC14, which is critical for its application in industrial bioprocesses.

Protocol 2: Engineering MoLAC14 for Improved Stability and Yield

- Objective: To improve the thermal stability and catalytic activity of MoLAC14 through site-directed mutagenesis.

- Principle: Targeted mutations are introduced into the MoLAC14 gene to stabilize the protein structure or alter active site residues, followed by functional screening of the variants [10] [16].

Materials and Methods:

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis:

- Mutations are introduced into the MoLAC14 gene sequence using techniques such as PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis.

- Key mutations that were experimentally validated include:

- Stability Mutations: E345P, G377P, H347F, E346C, E346F. These proline and residue substitutions were designed to enhance the rigidity and thermal stability of the enzyme [10].

- Activity Mutations: Alanine scanning was performed to identify essential residues. The mutation L532A was found to significantly boost magnolol production [10].

- Expression and Purification:

- The mutant genes are cloned and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) following Protocol 1.

- The mutant enzymes are purified for biochemical characterization.

- Biochemical Characterization:

- Thermal Stability Assay: The wild-type and mutant enzymes are incubated at elevated temperatures for a set period, and the residual activity is measured and compared.

- Activity Assay: Enzyme activity is measured by monitoring the rate of magnolol production from chavicol under standardized conditions.

Results and Performance Data: The engineered MoLAC14 variants showed marked improvements over the wild-type enzyme. The table below summarizes the quantitative enhancements achieved through protein engineering.

Table 1: Enhanced Performance of Engineered MoLAC14 Variants

| Mutation | Impact on Enzyme Properties | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| E345P, G377P, H347F, E346C, E346F | Notably enhanced thermal stability [10]. | Improved enzyme stability under process conditions. |

| L532A | Boosted magnolol production yield [10]. | Increased magnolol titer to an unprecedented level of 148.83 mg/L [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for the functional identification and characterization of laccases like MoLAC14, based on the protocols described.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Laccase Identification and Assay

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| pET-28a Vector | Expression vector for heterologous protein production in E. coli [10]. | Used for cloning MoLAC14 and its variants. |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | A robust host strain for recombinant protein expression [10] [16]. | Chemically transformed with the expression plasmid. |

| Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) | Inducer for triggering the expression of the target gene in the pET system [10] [16]. | Added to the bacterial culture to initiate laccase production. |

| Copper (II) Sulfate (CuSO₄) | Source of Cu²⺠ions essential for the assembly and function of the laccase multi-copper center [10] [16]. | Added to the culture medium during induction. |

| Chavicol | The phenolic substrate for the laccase-catalyzed reaction in magnolol synthesis [10]. | Converted to magnolol by MoLAC14. |

| ABTS (2,2'-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) | A common synthetic substrate used for high-throughput screening of laccase activity [16]. | Oxidation produces a colored product, easy to monitor. |

| HPLC-MS System | Analytical platform for separating, detecting, and confirming the identity of magnolol from reaction mixtures [10]. | Critical for validating the enzymatic function. |

| Monomethyl auristatin E intermediate-17 | Monomethyl auristatin E intermediate-17, MF:C27H35NO7S, MW:517.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cyromazine-3-mercaptopropanoic acid | Cyromazine-3-mercaptopropanoic Acid|Research Grade | Cyromazine-3-mercaptopropanoic acid is a research chemical for laboratory investigation. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The functional identification and subsequent engineering of the laccase MoLAC14 represent a significant advancement in the synthetic biology of magnolol production. The detailed protocols for transcriptome-driven gene discovery, heterologous expression, in vitro functional assays, and protein engineering provide a robust roadmap for researchers. The successful enhancement of MoLAC14's stability and yield through rational design underscores the potential of enzyme engineering in creating efficient biocatalysts. Integrating this optimized enzyme into engineered microbial hosts promises a sustainable and scalable manufacturing route for magnolol, overcoming the limitations of traditional plant extraction.

The identification of genes within biosynthetic pathways is a critical step in synthetic biology, particularly for the production of valuable plant-derived compounds like magnolol. Magnolol, a bioactive lignan from Magnolia officinalis, exhibits potent antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties but faces production challenges due to the plant's long cultivation time and low compound concentration [10] [8]. Traditional extraction and chemical synthesis methods are often inefficient, environmentally unsustainable, and produce low yields [8]. Synthetic biology offers a promising alternative, but its application requires a deep understanding of the underlying biosynthetic genes and pathways [10]. This application note details integrated genomic and transcriptomic protocols for discovering key genes, using the identification of the magnolol biosynthesis enzyme MoLAC14 as a case study. These methodologies enable researchers to move from raw multi-omics data to functionally validated genes, paving the way for the microbial production of magnolol and other high-value natural products.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Transcriptome Sequencing and Assembly for Pathway Hypothesis Generation

Principle: Comprehensive transcriptome sequencing across diverse plant tissues provides the foundational data to identify genes involved in specialized metabolism. This protocol focuses on generating a high-quality transcriptome assembly to probe the proposed magnolol biosynthetic pathway starting from chavicol [10].

Procedure:

- Tissue Collection: Collect multiple biological replicates (e.g., n=3-4) from various tissues (e.g., bark, leaves, roots) of Magnolia officinalis. Tissue selection should be informed by the known accumulation pattern of the target compound.

- RNA Extraction and QC: Extract total RNA using a standard kit (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy Plant Mini Kit). Assess RNA integrity and purity using an Agilent Bioanalyzer, ensuring all samples have an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8.0.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare strand-specific RNA-seq libraries (e.g., using Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA kit). Sequence the libraries on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq 6000) to a minimum depth of 6 Gb of high-quality (Q30 > 97%) data per sample [10].

- Read Processing and Assembly: Trim raw reads to remove adapters and low-quality bases using Trimmomatic. Map the high-quality reads to a reference genome of M. officinalis (if available) using HISAT2 or STAR. For de novo assembly, use Trinity software to reconstruct transcripts without a reference genome.

- Transcriptome Annotation: Perform functional annotation of the assembled transcripts using BLAST against databases like UniProt and Swiss-Prot, and assign Gene Ontology (GO) terms using tools like InterProScan.

Troubleshooting: Low mapping rates may indicate poor RNA quality or genomic divergence; consider de novo assembly. Incomplete BUSCO scores suggest an incomplete transcriptome; leverage multiple assembly algorithms and combine results.

Protocol 2: Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of Candidate Gene Families

Principle: Based on a biosynthetic hypothesis (e.g., laccase-mediated dimerization of chavicol to form magnolol), this protocol details the process of identifying all members of a target gene family and prioritizing candidates for functional testing [10].

Procedure:

- Family-Specific HMMER Search: Using hidden Markov models (HMMs) for the protein domain of interest (e.g., laccase, PFAM domain PF00394), search the annotated M. officinalis proteome using HMMER3 to identify all putative family members.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Calculate transcripts per million (TPM) values for each gene across all sequenced tissues. Perform differential expression analysis using DESeq2 or edgeR to identify genes highly expressed in tissues known to produce magnolol.

- Identification of Gene Clusters: Examine the genomic locations of the identified candidate genes. Genes arranged in tandem within a 100-200 Kb genomic region are considered part of a biosynthetic gene cluster. Identify such clusters as they are often linked to secondary metabolite pathways [10].

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Align the protein sequences of the candidate genes with homologs from model plants (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana) using MUSCLE. Construct a phylogenetic tree with IQ-TREE using maximum likelihood. Candidates that form species-specific clades or expand via tandem duplication are high-priority targets.

Troubleshooting: A large number of candidates can be prioritized by integrating expression levels (e.g., TPM > 50 in productive tissues) and phylogenetic clustering.

Protocol 3: Heterologous Expression and In Vitro Enzyme Activity Assay

Principle: This protocol validates the function of a candidate gene by heterologously expressing it in E. coli and testing its ability to convert a proposed substrate (chavicol) into the desired product (magnolol) in a controlled in vitro environment [10].

Procedure:

- Gene Synthesis and Cloning: Synthesize the codon-optimized coding sequence (CDS) of the candidate gene (e.g., MoLAC14). Clone the CDS into a protein expression vector (e.g., pET-28a) between NdeI and XhoI restriction sites using Gibson Assembly, resulting in an N-terminal His-tag fusion [10].

- Transformation and Expression: Chemically transform the constructed plasmid into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. Grow a culture in LB medium at 37°C until OD600 reaches 0.6-0.8. Induce protein expression with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and add 0.5 mM CuSO4 to the medium to facilitate laccase metallation. Incubate for 16-20 hours at 16°C.

- Protein Purification: Harvest cells by centrifugation and lyse via sonication. Purify the soluble His-tagged protein using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. Elute the protein with an imidazole gradient and desalt into an appropriate reaction buffer (e.g., 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0).

- In Vitro Enzyme Assay: In a reaction mixture, combine purified enzyme (e.g., 10 µg), substrate (chavicol, 1 mM), and buffer. Incubate at 30°C for 1-2 hours.

- Product Analysis by HPLC/MS: Stop the reaction by adding an equal volume of methanol. Analyze the metabolites via High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS). Identify magnolol by comparing its retention time and mass signature to an authentic standard.

Troubleshooting: Low protein solubility may require optimization of induction temperature and IPTG concentration. Lack of activity may indicate improper cofactor incorporation or the need for different reaction conditions (e.g., pH, oxygen availability).

Protocol 4: Enzyme Engineering for Enhanced Stability and Production

Principle: Once a key enzyme is identified, its properties can be improved through rational engineering. This protocol uses site-directed mutagenesis to enhance thermal stability and enzymatic activity, thereby increasing final product titers [10].

Procedure:

- Rational Mutagenesis Design: Based on structural models or homology to stable laccases, design mutations (e.g., E345P, G377P) to introduce stabilizing prolines or mutate residues in the substrate-binding pocket (e.g., L532A) [10].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Use a commercial kit (e.g., Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit, NEB) to introduce the desired mutations into the expression plasmid, following the manufacturer's instructions.

- Expression and Purification: Express and purify the mutant enzymes following steps 2-4 of Protocol 3.

- Thermal Stability Assay: Use a thermal shift assay (e.g., with Sypro Orange dye) to measure the melting temperature (Tm) of wild-type and mutant enzymes. An increase in Tm indicates improved stability.

- Fermentation and Titer Measurement: Express the best-performing mutant enzyme in a production host (e.g., engineered S. cerevisiae or E. coli) in a bioreactor. Quantify magnolol production in the culture medium over time using HPLC. The L532A mutation in MoLAC14 has been shown to boost magnolol production to 148.83 mg/L [10].

Troubleshooting: Some mutations may abolish activity; always screen multiple clones and characterize a range of mutations (e.g., via alanine scanning).

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Data from MoLAC14 Engineering

The following table summarizes the quantitative outcomes of engineering the key magnolol biosynthesis enzyme, MoLAC14, demonstrating the impact of specific mutations on thermal stability and product yield [10].

Table 1: Impact of MoLAC14 Mutations on Enzyme Properties and Magnolol Production

| Mutation | Property Targeted | Key Outcome | Reported Magnolol Titer |

|---|---|---|---|

| E345P, G377P | Thermal Stability | Enhanced stability | Not Specified [10] |

| H347F, E346C, E346F | Thermal Stability | Enhanced stability | Not Specified [10] |

| L532A | Enzymatic Activity | Boosted catalytic efficiency | 148.83 mg/L [10] |

| Wild-type MoLAC14 | (Baseline) | Baseline activity | Not Specified [10] |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential reagents and tools for executing the gene discovery and validation workflows described in this application note.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Omics-Driven Gene Discovery

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | Preparation of strand-specific RNA sequencing libraries. | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Preparation Kit |

| Sequence Assembly Software | De novo transcriptome assembly from RNA-seq reads. | Trinity (v2.15.1) |

| Protein Expression System | Heterologous expression and purification of candidate enzymes. | pET-28a vector in E. coli BL21(DE3); Ni-NTA Resin |

| Chromatography System | Separation, identification, and quantification of reaction products. | HPLC System with C18 column coupled to a Q-TOF Mass Spectrometer |

| Multi-omics Integration Tool | Computational integration of genomic, transcriptomic, and pharmacological data. | MiDNE (Multi-omics genes and Drugs Network Embedding) R package [17] |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Proposed Magnolol Biosynthesis Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the hypothesized biosynthetic pathway from chavicol to magnolol in Magnolia officinalis, culminating in the laccase-catalyzed coupling step validated in this study [10].

Proposed Biosynthesis Pathway

Gene Discovery and Validation Workflow

This diagram outlines the complete experimental workflow from tissue sampling and omics data generation to the final functional validation and engineering of the candidate gene.

Gene Discovery Workflow

Building Cell Factories: Engineering Microbial Hosts and Biosynthesis Pathways

Synthetic biology provides a powerful framework for engineering cellular factories to produce high-value natural compounds like magnolol, a potent antibacterial plant-derived molecule [5]. Central to this endeavor is the selection of an appropriate microbial chassis—a host organism engineered to carry out a desired biological function. The ideal chassis determines the efficiency, yield, and scalability of the entire bioprocess. Escherichia coli and various yeast species, particularly Saccharomyces cerevisiae, stand as the foundational workhorses in this field due to their well-characterized genetics, rapid growth, and the extensive availability of synthetic biology tools [18]. This article examines the prospects of these and other chassis organisms, providing a structured comparison and detailed experimental protocols, all framed within the context of optimizing magnolol production.

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Chassis Organisms

Selecting a host organism involves balancing factors such as growth rate, ability to perform complex modifications, yield, and cost. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the most commonly used microbial systems.

Table 1: Key Features of Promising Microbial Chassis Organisms

| Aspect | Escherichia coli | Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Yeast) | Pichia pastoris (Yeast) | Bacillus subtilis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Advantages | Rapid growth, easy genetic manipulation, low cost, extensive molecular tool availability [19] [20] | Performs eukaryotic post-translational modifications (PTMs), well-established engineering toolkit, robust [18] [20] | High cell density fermentation, performs glycosylation, strong inducible promoters [20] | Naturally secretes proteins, GRAS status, simplified purification [20] |

| Key Limitations | Limited PTMs, formation of inclusion bodies, lower tolerance to some flavonoids [19] [21] | Longer doubling time than bacteria, more complex genetics, higher cost than bacterial systems [19] [20] | Requires precise optimization, higher cost compared to bacterial systems, methanol use in some systems [20] | Limited PTMs, requires strain-specific optimization for some proteins [20] |

| Post-Translational Modifications | Minimal to none [20] | Yes (e.g., glycosylation) [20] | Yes (e.g., eukaryotic-like glycosylation) [20] | Minimal to none [20] |

| Typical Protein Yield | 1-10 g/L (intracellular) [19] | Up to 20 g/L (reported for various proteins) [19] | Information not specified in search results | Information not specified in search results |

| Growth Rate | Very fast (doubling time ~20 min) [20] | Moderate (doubling time ~2 hours) [20] | Moderate | Moderate (doubling time ~30-60 min) [20] |

| Ideal Applications | Enzymes, small therapeutic proteins, simple natural products [20], flavonoid glycosylation [21] | Production of complex therapeutic proteins, secondary metabolites requiring eukaryotic PTMs [18] [19] | Therapeutic proteins, enzymes requiring glycosylation [20] | Industrial enzymes, bulk production of soluble proteins [20] |

For magnolol production, which involves the dimerization of chavicol, the choice of chassis is critical. Research has identified the laccase enzyme MoLAC14 as the key catalyst for this one-step conversion [5]. A chassis like E. coli may be sufficient if the laccase can be functionally expressed and the product does not require further eukaryotic-specific modifications. However, non-model E. coli strains can offer significant advantages. For instance, E. coli W has demonstrated enhanced tolerance to toxic flavonoids like chrysin compared to the standard K-12 strain, making it a superior platform for flavonoid glycosylation processes [21]. For more complex pathways where subcellular compartmentalization or specialized PTMs are beneficial, a yeast chassis like S. cerevisiae might be preferable.

Application Notes: Chassis Engineering for Magnolol Production

Case Study: Establishing a RobustE. coliPlatform

A recent study exemplifies the systematic engineering of a chassis for flavonoid bioprocessing. Researchers selected E. coli W for its innate resilience and ability to utilize sucrose, a low-cost carbon source. To enhance its performance, they employed a two-pronged approach:

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): The strain was evolved under sucrose selection pressure to optimize its native sucrose metabolism [21].

- Targeted Metabolic Engineering: Key genes (xylA, zwf, pgi) were knocked out to reroute intracellular carbon flux away from biomass and toward the synthesis of uridine diphosphate glucose (UDPG), a crucial precursor for glycosylation reactions [21]. This engineered chassis, when applied to the glycosylation of the flavonoid chrysin, achieved a remarkable titer of 1844 mg/L in a scaled-up fed-batch bioreactor [21]. This demonstrates the power of combining chassis innate properties with advanced engineering to overcome bioprocess constraints like precursor availability and product toxicity.

Protocol: In Vivo Magnolol Production in EngineeredE. coli

This protocol details the steps for producing magnolol in an engineered E. coli chassis by expressing the key laccase gene MoLAC14 from Magnolia officinalis [5].

Principle: The protocol leverages recombinant DNA technology to introduce the plant-derived MoLAC14 gene into E. coli. The engineered host then expresses the laccase enzyme, which catalyzes the oxidative coupling of two chavicol molecules to form magnolol [5].

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for the production and analysis of magnolol in an engineered E. coli system.

Materials:

- Strain: E. coli BL21(DE3) or other suitable expression host.

- Vector: pET-28a plasmid (or similar with T7/lac promoter and antibiotic resistance) [5].

- Gene: Codon-optimized MoLAC14 gene (GenBank accession number can be found in [5]).

- Media: LB broth and agar plates with appropriate antibiotic (e.g., 50 µg/mL kanamycin for pET-28a).

- Inducer: Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG).

- Substrate: Chavicol.

- Equipment: Shaking incubator, centrifuge, spectrophotometer, HPLC system, mass spectrometer.

Procedure:

- Plasmid Construction: Subclone the MoLAC14 coding sequence into the pET-28a expression vector between the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites using standard molecular biology techniques or Gibson assembly [5].

- Transformation: Introduce the constructed plasmid into chemically competent E. coli BL21(DE3) cells via heat shock transformation. Plate the cells on LB agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotic and incubate overnight at 37°C.

- Culture and Induction: Inoculate a single colony into 5 mL of LB medium with antibiotic and grow overnight at 37°C with shaking. Use this starter culture to inoculate a larger culture (e.g., 50-100 mL) at a 1:100 dilution. Grow the culture at 37°C until the OD600 reaches approximately 0.6. Add IPTG to a final concentration of 0.1-1.0 mM to induce laccase expression. Lower the temperature to 25-30°C and continue incubation for 4-16 hours.

- Biotransformation: Add chavicol (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mM) to the induced culture and incubate further for 12-24 hours to allow for enzymatic conversion to magnolol.

- Product Extraction: Harvest the cells by centrifugation (e.g., 4,000 x g for 20 minutes). Resuspend the cell pellet in methanol or ethyl acetate and vortex vigorously to extract magnolol. Separate the organic solvent phase by centrifugation.

- Analysis:

- HPLC: Analyze the extract using reverse-phase HPLC. Monitor for a peak corresponding to the magnolol standard (retention time ~15.3 minutes under conditions in [5]).

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Confirm the identity of the product using LC-MS. Magnolol has a molecular weight of 266.1 g/mol, and the [M-H]â» ion is typically observed at m/z 265 [5].

Protocol: Engineering Enhanced Enzyme Activity for Improved Titer

A critical strategy in synthetic biology is to optimize the pathway enzymes themselves. This protocol describes the engineering of MoLAC14 for improved thermal stability and activity, which directly translates to higher magnolol production [5].

Principle: Through site-directed mutagenesis, specific amino acid residues in the laccase enzyme are altered. These mutations can enhance protein stability and catalytic efficiency, leading to a more effective whole-cell biocatalyst.

Workflow: The diagram below outlines the key steps in the enzyme engineering and validation cycle.

Materials:

- Template: Plasmid containing the wild-type MoLAC14 gene.

- Primers: Mutagenic primers designed for the target site (e.g., to introduce the L532A mutation).

- Kit: Site-directed mutagenesis kit.

- Equipment: Thermocycler, equipment for protein purification (e.g., affinity chromatography), spectrophotometer for enzyme assays, thermal block.

Procedure:

- Mutation Design: Based on structural models or alignments with stable laccases, design mutations. For MoLAC14, mutations like E345P, G377P, and L532A have been shown to improve stability and activity [5].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Perform the mutagenesis reaction according to the manufacturer's protocol to create the variant MoLAC14 plasmid.

- Expression and Purification: Transform, express, and purify the wild-type and mutant enzymes as described in the previous protocol.

- Enzyme Assay: Measure laccase activity by monitoring the oxidation of a substrate like ABTS (2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) at 420 nm, or directly by quantifying magnolol production from chavicol via HPLC.

- Thermal Stability Assay: Incubate the purified enzymes at a elevated temperature (e.g., 50°C) for a set time. Remove aliquots at regular intervals and measure the remaining activity. The half-life of the mutant enzyme should be compared to the wild-type.

- Whole-Cell Validation: Introduce the best-performing mutant gene into the production chassis and run the magnolol production protocol. The L532A mutation, for example, boosted magnolol production to 148.83 mg/L in a laboratory setting [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Synthetic Biology-Driven Magnolol Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Application in Magnolol Research |

|---|---|

| pET-28a Vector | A common protein expression plasmid used for heterologous expression of the MoLAC14 laccase gene in E. coli [5]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Enables precise, scarless genome editing in chassis organisms (e.g., E. coli, yeast) for metabolic engineering, such as knocking out genes to redirect metabolic flux [18] [21] [22]. |

| Chavicol | The direct phenolic precursor molecule that is dimerized by the laccase enzyme MoLAC14 to form magnolol [5]. |

| UDP-Glucose (UDPG) | A key nucleotide sugar precursor for glycosylation reactions. Enhancing its intracellular availability is critical for producing glycosylated flavonoids, which can improve solubility and bioavailability [21]. |

| Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) | A technique used to enhance desired chassis properties, such as improved sucrose metabolism or flavonoid tolerance, by applying long-term selective pressure [21]. |

| Thalidomide-4-NH-PEG1-COO(t-Bu) | Thalidomide-4-NH-PEG1-COO(t-Bu), MF:C22H27N3O7, MW:445.5 g/mol |

| Angiotensinogen (1-13) (human) | Angiotensinogen (1-13) (human), MF:C79H116N22O17, MW:1645.9 g/mol |

The strategic selection and engineering of a microbial chassis are paramount for the successful synthetic production of magnolol. E. coli offers a fast, tractable, and cost-effective system, with non-model strains like E. coli W providing enhanced robustness for toxic compounds. Yeast chassis provide essential eukaryotic machinery for more complex engineering tasks. The decision must be guided by the specific pathway requirements, with recent advances in genome editing, enzyme engineering, and bioprocess optimization providing the necessary tools to tailor these hosts for high-value compound production. The protocols and application notes outlined here provide a concrete foundation for researchers to engineer and deploy these microbial workhorses effectively.

Within synthetic biology frameworks, the efficient production of plant-derived natural products like magnolol relies on the precise design of genetic vectors and their successful introduction into a microbial host. Magnolol, a bioactive neolignan from Magnolia officinalis, exhibits a broad range of pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, and anti-parasitic effects, making it a compelling target for bioproduction [9] [7]. Traditional extraction from magnolia bark is inefficient due to long cultivation times and low compound concentration, typically around 1% [5]. Synthetic biology offers a sustainable alternative by enabling the heterologous production of such valuable compounds in engineered microorganisms. This application note details the core principles and protocols for constructing the biosynthetic machinery for magnolol production, providing a guide for researchers and scientists in drug development.

Biosynthetic Pathway and Key Enzyme Identification

The proposed biosynthetic pathway for magnolol in Magnolia officinalis begins with tyrosine. Through a series of enzymatic steps involving tyrosine ammonia-lyase (TAL), 4-coumarate CoA ligase (4CL), cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), p-coumaryl alcohol is produced. This intermediate is then converted to chavicol by enzymes including coniferyl alcohol acetyltransferase (CAAT) and allylphenol synthases (APS) [5].

Critically, research indicates that magnolol is synthesized from the precursor chavicol in a one-step reaction catalyzed by the enzyme laccase [5]. Leveraging transcriptome data from M. officinalis, 30 potential laccase genes were identified. Among them, MoLAC14 was functionally validated in vitro as the pivotal enzyme responsible for the oxidative coupling of two chavicol molecules to form magnolol [5].

Table 1: Key Enzymes in the Proposed Magnolol Biosynthetic Pathway

| Enzyme | Abbreviation | Function in Magnolol Biosynthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Tyrosine ammonia-lyase | TAL | Converts tyrosine to coumaric acid |

| 4-coumarate CoA ligase | 4CL | Activates coumaric acid to form coumaroyl-CoA |

| Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase | CCR | Reduces coumaroyl-CoA to cinnamaldehyde |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase | ADH | Reduces cinnamaldehyde to cinnamyl alcohol |

| Allylphenol synthase | APS | Converts p-coumaryl alcohol to chavicol |

| Laccase (MoLAC14) | LAC | Oxidatively dimerizes chavicol to form magnolol |

Vector Design and Engineering of MoLAC14

Basic Vector Construction

The coding sequence (CDS) of the target laccase gene, MoLAC14, should be cloned into an appropriate expression vector. For initial functional validation in E. coli, the following design is recommended:

- Vector Backbone: pET-28a is a suitable choice for high-level expression in E. coli [5].

- Cloning Sites: Integration of the gene between the Nde I and Xho I restriction sites.

- Assembly Method: The vector can be constructed using Gibson assembly, a method noted for its use in assembling biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) [5] [23].

This basic vector, pET-28a-MoLAC14, allows for inducible expression of the laccase enzyme to test its activity in converting chavicol to magnolol.

Enzyme Engineering for Enhanced Stability and Activity

Wild-type enzymes often require optimization for efficient industrial application. Engineering of MoLAC14 has demonstrated significant improvements in thermal stability and activity [5]. The following single-point mutations were identified as beneficial:

Table 2: MoLAC14 Mutations for Improved Performance

| Mutation | Impact on Enzyme Properties |

|---|---|

| E345P | Enhanced thermal stability |

| G377P | Enhanced thermal stability |

| H347F | Enhanced thermal stability |

| E346C | Enhanced thermal stability |

| E346F | Enhanced thermal stability |

| L532A | Increased magnolol production titer |

Alanine scanning, a technique for identifying essential residues, led to the discovery of the L532A mutation, which boosted magnolol production to 148.83 mg/L in a fermentation context, underscoring the critical role of protein engineering in synthetic biology [5].

Host Selection and Transformation

Chassis Selection

While E. coli is a common host for initial gene characterization and pathway validation, the choice of a production chassis is critical. For complex natural products like type II polyketides, Streptomyces species are often superior due to their native capacity for secondary metabolism and precursor supply [24]. A engineered strain of Streptomyces aureofaciens, dubbed "Chassis2.0," was developed by deleting endogenous gene clusters to minimize precursor competition. This chassis has shown high efficiency in producing diverse aromatic polyketides and serves as an excellent model for a versatile production platform [24].

Transformation Protocol

The following protocol details the transformation of a Streptomyces chassis, which is a critical step in establishing the biosynthetic machinery.

Materials:

- Streptomyces aureofaciens Chassis2.0 spores or mycelia [24]

- pET-28a-MoLAC14 plasmid DNA (or a suitable Streptomyces shuttle vector containing the gene of interest)

- Lysozyme solution (10 mg/mL)

- Sucrose solution (10.3%)

- Regeneration Medium (e.g., R2YE or R5 agar)

- Antibiotics for selection (e.g., apramycin)

Procedure:

- Preparation of Protoplasts: a. Inoculate a flask of TSB (Tryptic Soy Broth) with Streptomyces spores and incubate at 30°C with shaking until late-exponential growth phase (approx. 36-48 hours). b. Harvest the mycelia by centrifugation (3,000 - 4,000 × g for 10 minutes). c. Wash the pellet gently with 10.3% sucrose solution. d. Re-suspend the mycelia in a lysozyme solution (1-2 mg/mL in 10.3% sucrose) and incubate at 30°C for 30-60 minutes. Monitor protoplast formation under a microscope.

Transformation: a. Carefully pellet the protoplasts by gentle centrifugation (2,000 × g for 7-10 minutes). b. Wash the protoplast pellet twice with 10.3% sucrose to remove residual lysozyme. c. Re-suspend the protoplasts in a small volume of 10.3% sucrose. d. Aliquot protoplasts into microcentrifuge tubes and add the plasmid DNA (approx. 100-500 ng). Mix gently. e. Add an equal volume of 40% PEG 1000 (Polyethylene Glycol) to the protoplast-DNA mixture. Mix by gentle pipetting and incubate at room temperature for 1-2 minutes.

Regeneration and Selection: a. Dilute the transformation mixture with 1-2 mL of 10.3% sucrose. b. Plate the protoplasts onto Regeneration Medium (R2YE or R5 agar) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic. c. Allow the plates to dry and incubate at 30°C for 5-7 days until transformant colonies appear.

Verification: a. Screen the resulting colonies by PCR using gene-specific primers for MoLAC14 to confirm the successful integration of the construct [5]. b. For strains harboring the complete biosynthetic pathway, confirm magnolol production via High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Mass Spectrometry (MS) [5].

Flowchart of Streptomyces Transformation and Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Magnolol Biosynthesis Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| pET-28a Vector | Prokaryotic expression vector for gene cloning and protein expression in E. coli. | Contains T7 lac promoter for inducible expression [5]. |

| Golden Gate Assembly (GGA) | A modular cloning system for efficient and accurate assembly of multiple DNA fragments. | Enables 100% efficient construction of BGCs and mutant libraries [23]. |

| Gibson Assembly | An isothermal, single-reaction method for assembling multiple overlapping DNA fragments. | Used for constructing expression plasmids and BGCs [5]. |

| Chassis2.0 | An engineered Streptomyces aureofaciens strain optimized for production of aromatic polyketides. | Deletion of native BGCs reduces precursor competition [24]. |

| Chavicol | The direct precursor substrate for the final enzymatic step in magnolol synthesis. | Used in in vitro assays and as a fed substrate in fermentations [5]. |

| R2YE / R5 Agar | Regeneration media used for the recovery and growth of Streptomyces protoplasts after transformation. | Essential for obtaining transformants post-PEG treatment. |

| 7-Hydroxymethyl-10,11-MDCPT | 7-Hydroxymethyl-10,11-MDCPT, MF:C22H18N2O7, MW:422.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tricyclodecenyl acetate-13C2 | Tricyclodecenyl acetate-13C2, MF:C12H16O2, MW:194.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Analytical Methods for Validation

Confirming successful magnolol production is a multi-step process:

- HPLC (High-Performance Liquid Chromatography): Separates and analyzes the components of the culture extract, allowing for the identification of magnolol based on its retention time compared to an authentic standard.

- MS (Mass Spectrometry): Provides the molecular mass and fragmentation pattern of the produced compound, offering definitive confirmation of magnolol identity [5].

- GNPS Molecular Networking: This advanced technique can be used to identify not only the target compound but also related molecules and shunt products, which is particularly useful when refactoring pathways or generating mutant libraries [23].

Concluding Remarks

The construction of efficient biosynthetic machinery for magnolol production hinges on the synergistic application of optimized vector design, precise enzyme engineering, and the selection of a compatible microbial chassis. The protocols outlined here—from cloning the key laccase gene MoLAC14 and improving its properties through site-directed mutagenesis, to transforming a high-performance Streptomyces chassis—provide a robust framework for researchers. This approach, firmly situated within the principles of synthetic biology, enables the sustainable and scalable production of magnolol, facilitating further pharmacological studies and drug development efforts for this promising natural compound.

HERE IS THE DRAFT OF YOUR APPLICATION NOTES AND PROTOCOLS

Heterologous Expression of Key Enzymes: Case Study on MoLAC14 Production

Within the broader framework of developing a robust synthetic biology platform for the production of magnolol, a plant-derived compound with significant antimicrobial and therapeutic potential, the heterologous expression of key biosynthetic enzymes is a critical step [5]. The traditional extraction of magnolol from the bark of Magnolia officinalis is constrained by the plant's long growth cycle and the low concentration of the compound (~1%) [5] [8]. Furthermore, chemical synthesis routes often suffer from poor specificity, low yield, and environmental concerns [5] [8]. Synthetic biology offers a promising alternative, but its application for magnolol production has been hampered by a lack of understanding of its biosynthetic pathway in the plant [5].

Recent research has identified MoLAC14, a laccase enzyme from Magnolia officinalis, as a pivotal catalyst in the biosynthesis of magnolol, directly converting the precursor chavicol into magnolol [5]. This discovery provides a foundational genetic component for engineering a microbial cell factory. The functional expression of MoLAC14 in a heterologous host is therefore a cornerstone for enabling the sustainable bioproduction of magnolol. This document details the application notes and protocols for the heterologous production and engineering of MoLAC14, serving as a case study for the expression of key plant-derived enzymes in a synthetic biology context.

Key Findings and Quantitative Data

The identification and subsequent engineering of MoLAC14 have yielded critical quantitative data that inform the strategy for its heterologous production. The functional characterization confirmed its central role in magnolol biosynthesis, while protein engineering significantly enhanced its properties.

Table 1: Summary of Key Experimental Findings for MoLAC14

| Aspect | Finding | Implication for Heterologous Production |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Function | Confirmed to catalyze the one-step conversion of chavicol to magnolol [5]. | Validates MoLAC14 as the key gene for a simplified magnolol biosynthetic pathway in a heterologous host. |

| Critical Residue | Alanine scanning identified L532 as an essential residue; the L532A mutation enhanced activity [5]. | Indicates a key target for further rational protein engineering to improve enzyme performance. |

| Production Titre | The L532A variant boosted magnolol production to a level of 148.83 mg/L in vitro [5]. | Provides a benchmark for evaluating the success of heterologous expression and fermentation processes. |

| Thermal Stability | Mutations E345P, G377P, H347F, E346C, and E346F notably improved thermal stability [5]. | Crucial for industrial application; stable enzymes can withstand prolonged fermentation conditions and storage. |

Experimental Protocols

Gene Identification and Cloning of MoLAC14

The initial discovery of MoLAC14 involved comprehensive transcriptome sequencing of various M. officinalis tissues, which led to the identification of 30 potential laccase genes [5]. MoLAC14 was selected for functional characterization based on its high expression in magnolol-producing tissues and its presence in a putative biosynthetic gene cluster [5].

Protocol: Gene Cloning into a Prokaryotic Expression Vector

- Gene Synthesis: The coding sequence (CDS) of MoLAC14 was retrieved from the M. officinalis transcriptome and genome data. The gene was synthesized de novo with codon optimization for the intended expression host (e.g., E. coli) to improve translation efficiency [5].

- Vector Preparation: A pET-28a vector is linearized using restriction enzymes Nde I and Xho I [5]. This vector provides a T7 lac promoter for strong, inducible expression and an N-terminal hexahistidine (His6)-tag for simplified purification.