Dynamic Control of Biosynthetic Reactor Parameters: Enhancing Robustness, Yield, and Scalability in Bioprocessing

This article provides a comprehensive overview of dynamic control strategies for optimizing biosynthetic reactor parameters, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Dynamic Control of Biosynthetic Reactor Parameters: Enhancing Robustness, Yield, and Scalability in Bioprocessing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of dynamic control strategies for optimizing biosynthetic reactor parameters, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of moving beyond static engineering to adaptive metabolic control, detailing methodologies such as synthetic genetic circuits, biosensors, and model-based optimization. The content addresses critical challenges in process robustness and scale-up, offering troubleshooting and optimization frameworks including Design of Experiments (DoE) and process intensification. Finally, it examines validation through case studies and comparative analyses across microbial and cell culture systems, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for biomedical and clinical research applications.

The Principles of Dynamic Control: Moving Beyond Static Metabolic Engineering

Defining Dynamic Control in Biosynthetic Systems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is dynamic control in biosynthetic systems? Dynamic control refers to the real-time, automated regulation of cellular processes in engineered biological systems. Unlike static engineering, where genetic modifications are permanent, dynamic control uses genetic circuits, biosensors, and control algorithms to allow cells to sense their environment and adjust metabolic flux, gene expression, or enzyme activity accordingly. This enables autonomous adaptation to changing conditions, such as nutrient availability or the accumulation of toxic intermediates, leading to improved product yields and more robust bioprocesses [1] [2].

2. Why is dynamic control superior to static engineering for some applications? Static engineering, like the constitutive overexpression of a pathway gene, applies a constant genetic change. This can be detrimental if the product or intermediate is toxic, as it can arrest cell growth early in fermentation. Dynamic control separates growth and production phases or fine-tunes pathway expression in response to metabolite levels. This maintains metabolic homeostasis, prevents the accumulation of toxic compounds, and has been shown to increase production titers by over 48% and improve cell growth by 21% in some cases [3] [2].

3. What are the core components of a dynamic control system? A functional dynamic control system typically requires three key components:

- A Biosensor: A biological module that detects a specific intracellular or extracellular stimulus (e.g., metabolite concentration, pH, oxygen). This can be a transcription factor that binds a metabolite or a two-component system [3] [2].

- A Actuator: The element that executes the control action. This is often a regulated promoter that drives the expression of a target gene (e.g., a pathway enzyme, a CRISPRi system for gene knockdown, or a protease for targeted protein degradation) [4] [2].

- A Genetic Circuit: The logic that processes the information from the biosensor and directs the actuator. This can be as simple as a single promoter-reporter system or a complex combinatorial logic circuit that integrates multiple inputs to make a decision [2].

4. I am experiencing low product yield despite high pathway expression. Could dynamic control help? Yes, this is a classic scenario where dynamic control is beneficial. High, constant expression of a biosynthetic pathway can create a massive metabolic burden, diverting resources (energy, precursors) away from cell growth and health, ultimately limiting overall production. A dynamic system can be designed to only activate the pathway once a sufficient cell density is reached or when a key precursor metabolite accumulates, thereby balancing growth and production for a higher final titer [2].

5. My biosensor shows a weak response or low dynamic range. How can I improve it? Biosensor performance can often be enhanced through protein and promoter engineering. Strategies include:

- Key Point Mutations: Introducing mutations into the sensor protein (e.g., a transcription factor) to alter its ligand-binding affinity or its interaction with RNA polymerase [3].

- Promoter Engineering: Modifying the sequence of the output promoter to fine-tune its strength and regulation, thereby amplifying the "ON" signal and minimizing the "OFF" state leakage [3].

- Circuit Integration: Using the sensor to drive a genetic circuit that amplifies the signal, such as a positive feedback loop or a multi-stage cascade [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Biosensor Fails to Activate or Responds Incorrectly

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No output signal despite high inducer concentration. | The biosensor circuit is not functional due to genetic defects. | Verify plasmid construction and gene sequence. Check for successful expression of all biosensor components (e.g., sensor protein, output reporter). |

| Weak output signal (low dynamic range). | Poor affinity between the sensor and the target metabolite. Weak or leaky output promoter. | Engineer the sensor protein for higher affinity or sensitivity [3]. Screen a library of mutant promoters to find a variant with stronger induction and lower background expression [3]. |

| Sensor activates at the wrong time or to the wrong stimulus. | The sensor is cross-reacting with other cellular metabolites. The genetic circuit logic is flawed. | Characterize sensor specificity. Re-engineer the sensor for greater specificity or implement a combinatorial logic circuit that requires multiple inputs to activate, making the response more specific to the desired condition [2]. |

Problem: High Metabolic Burden or Cell Toxicity in Production Phase

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Cell growth is severely inhibited upon induction of the production pathway. | Accumulation of a toxic intermediate or product. Overexpression of pathway enzymes drains essential precursors (e.g., ATP, NADPH). | Implement dynamic control to delay pathway expression until high cell density is achieved [2]. Use a biosensor for the toxic compound to downregulate its own synthesis in real-time [4]. |

| High rates of cell death or mutation during fermentation. | The target product is cytotoxic at high concentrations. | Dynamically control product export pumps. Use a two-stage process where growth and production are physically or temporally separated [4] [3]. |

| Unwanted byproducts divert flux away from the target product. | Competitive metabolic pathways are active. | Use dynamic regulation to knock down competing pathways only when the key intermediate is present, redirecting flux toward the desired product [4]. |

Quantitative Data in Dynamic Control Experiments

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Static vs. Dynamic Control Strategies

| Product | Host Organism | Control Strategy | Key Performance Metric | Result with Dynamic Control | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xylitol | E. coli | Static Overexpression | Final Titer | Baseline | [4] |

| Dynamic (Regulatory) | Final Titer | 90-fold improvement | [4] | ||

| Cadaverine | E. coli | Constitutive Expression | Final Titer | 22.41 g/L | [3] |

| Lysine Biosensor Dynamic Regulation | Final Titer | 33.19 g/L (48.1% increase) | [3] | ||

| Constitutive Expression | Cell Growth (OD600) | Baseline | [3] | ||

| Lysine Biosensor Dynamic Regulation | Cell Growth (OD600) | 21.2% increase | [3] | ||

| NADPH flux for Xylitol biosynthesis | E. coli | Static (Stoichiometric) | Production Improvement | 20-fold | [4] |

| Dynamic (Regulatory) | Production Improvement | 90-fold | [4] |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Dynamic Control

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Dynamic Control | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) | Allows for targeted, reversible gene knockdown. An output promoter can express a guide RNA (gRNA) to silence a specific gene in response to a sensor. | Dynamically turning off a competitive metabolic pathway when a key intermediate is sensed [4] [2]. |

| Targeted Proteolysis Systems | Enables controlled degradation of specific proteins. A degradation tag (e.g., DAS+4) is fused to a target protein, and a separately induced protease (e.g., ClpXP with SspB) breaks it down. | Dynamic reduction of enzyme levels to redirect metabolic flux, as used in 2-stage dynamic metabolic control [4]. |

| Two-Component System Biosensors | Native bacterial systems that sense an extracellular signal (e.g., metabolite, pH) and phosphorylate a response regulator to activate transcription. | The CadC/LysP system was engineered to sense lysine and dynamically regulate cadaverine synthesis [3]. |

| Orthogonal RNA Polymerases | Allows for modular circuit design. A sensor-driven promoter can control an RNA polymerase, which then transcribes a separate set of output genes. | Creating complex genetic circuits with multiple outputs or cascading signals without cross-talk from the host [2]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Lysine Biosensor for Dynamic Control of Cadaverine Production

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully increased cadaverine production by 48.1% using dynamic regulation [3].

Objective: To construct an engineered E. coli strain where the expression of the cadaverine biosynthesis pathway (e.g., the cadA gene encoding lysine decarboxylase) is dynamically regulated by intracellular lysine levels.

Materials:

- Strains: E. coli MG1655 or similar production chassis.

- Plasmids: Vectors for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, plasmid with inducible promoter for heterologous expression.

- Reagents: Primers for gene cloning and editing, Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, seamless cloning kit, antibiotics, lysine hydrochloride, MOPS medium components, glucose, trace elements.

Procedure:

Step 1: Biosensor Construction and Optimization

- Clone Core Components: Assemble the lysine biosensor on a plasmid. The core components include:

- The gene for the transcription factor CadC.

- The gene for the lysine transporter LysP.

- The Pcad promoter (the native promoter regulated by CadC).

- A reporter gene (e.g., GFPuv) under the control of Pcad for initial characterization.

- Improve Biosensor Performance: The native CadC/LysP system operates at low pH. To make it functional for fermentation (near neutral pH), perform multilevel optimization:

- Introduce point mutations into CadC (e.g., based on literature or random mutagenesis) to shift its pH sensitivity and increase responsiveness to lysine.

- Engineer the Pcad promoter by creating a library of mutants with varying strengths. Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to select variants with high GFP expression in the presence of lysine and low expression in its absence, maximizing the dynamic range [3].

Step 2: Engineering the Production Strain

- Modify the Host Genome: Use CRISPR/Cas9 to engineer the E. coli host for high lysine production.

- Knock out genes responsible for lysine and cadaverine degradation (e.g., cadA).

- Introduce feedback-resistant mutations in the lysine biosynthetic pathway (e.g., in dapA) to increase lysine flux.

- Overexpress key lysine biosynthesis genes (e.g., lysC, dapB) under strong, constitutive promoters.

- Integrate the Dynamic Control System: Replace the GFPuv reporter in the optimized biosensor plasmid with the cadA gene (lysine decarboxylase). This creates the final dynamic control construct: high lysine -> CadC activation -> Pcad induction -> CadA expression -> lysine conversion to cadaverine.

Step 3: Fermentation and Validation

- Shake Flask Characterization: Inoculate the engineered strain and a control strain (with constitutive cadA expression) in MOPS medium with glucose. Monitor OD600 and GFP fluorescence (if a reporter is included) over time. Add lysine at different points to verify sensor response.

- Fed-Batch Bioreactor Fermentation:

- Inoculate a 5L bioreactor with a 2L working volume of defined medium.

- Maintain culture conditions: pH at 6.8-7.0, dissolved oxygen at 30%, temperature at 37°C.

- Use a feeding solution (625 g/L glucose, 100 g/L (NH4)2SO4) to maintain residual glucose at ~10 g/L.

- Periodically sample the broth to measure OD600, lysine, and cadaverine concentrations (e.g., via HPLC).

- Analysis: Compare the growth (OD600) and cadaverine titer of the dynamically controlled strain against the constitutively expressed control. The successful implementation should show improved cell growth and a significantly higher final cadaverine titer [3].

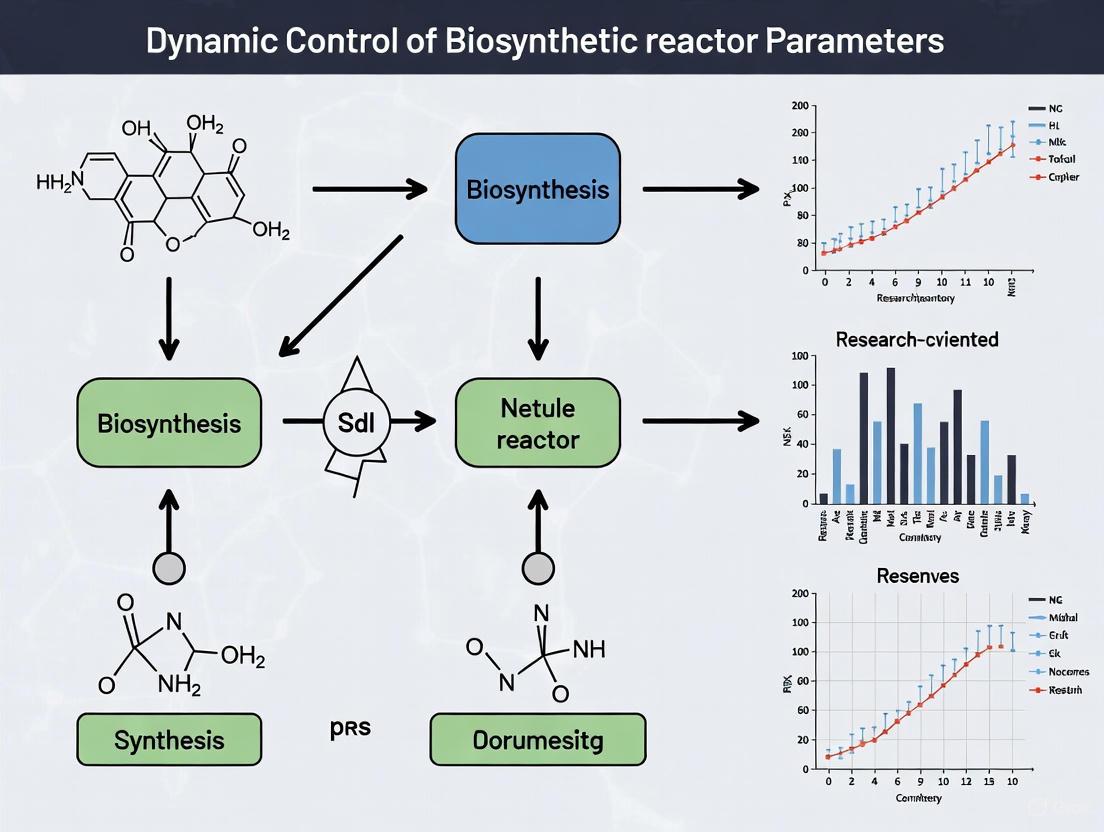

Experimental Workflow Diagram

Dynamic Control Implementation Workflow

Biosensor Mechanism Diagram

Lysine-Responsive Biosensor Mechanism

The Critical Challenge of Process Robustness and Scalability in Industrial Bioprocesses

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common root causes of quality defects in biopharmaceutical manufacturing? Unexpected quality problems often arise from contaminated raw materials, malfunctions in production equipment, or cross-contaminations due to non-compliance with hygiene procedures. These incidents necessitate an immediate root cause analysis to prevent future defects and ensure patient safety [5].

Q2: How can Artificial Intelligence (AI) enhance the robustness of a fermentation process? AI-driven control frameworks integrate data-driven decision-making with real-time sensing to dynamically regulate microbial metabolism. For instance, one study used a backpropagation neural network (BPNN) to model kinetics, achieving a 75.7% improvement in gentamicin C1a production titer over traditional methods by enabling real-time coordination of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen supplementation [6].

Q3: What analytical techniques are best for identifying an unknown particulate contamination? A combination of physical and chemical methods is most effective. Initial, non-destructive steps include:

- Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX): For chemical identification of inorganic compounds and surface topography.

- Raman Spectroscopy: For analyzing organic particles. If solubility tests allow, further structure elucidation can be performed using techniques like LC-HRMS (Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry) or GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) [5].

Q4: Why is temperature control critical in fermentation, and what are advanced control strategies? Temperature directly impacts fermentation efficiency and can denature microorganism proteins. Advanced strategies go beyond traditional PID controllers. For example, an optimal Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) control acting on the coolant flow through the reactor jacket can efficiently maintain the desired temperature, even when accounting for asymmetric heat transfer effects modeled with fractional-order derivatives [7].

Q5: What key factors should be considered during bioreactor scale-up to maintain process robustness? Scale-up must address gas mass transfer, particularly dissolved COâ‚‚ (dCOâ‚‚) accumulation. Traditional criteria like equal power per unit volume (P/V) or oxygen mass transfer coefficient (kLa) may not sufficiently control dCOâ‚‚ levels. A comprehensive scale-up strategy should ensure similarity in critical parameters like pH and partial pressure of COâ‚‚ (pCOâ‚‚) across different bioreactor scales [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Particulate Contamination in a Bioprocess Stream

This guide outlines a systematic approach for root cause analysis of visible particulate matter.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Problem Containment & Description:

- Immediately stop the production process and isolate affected batches.

- Document the problem in detail: What was observed? When was it first noticed? Which equipment and raw materials were involved? [5]

Information Gathering:

- Collect all relevant data, including batch records, personnel involved, and samples of the contaminated product and source materials.

Analytical Strategy Formulation:

- Design a parallel analytical strategy using complementary techniques to save time [5].

Physical Analysis (Fast, Non-destructive):

- Method: Analyze particles using SEM-EDX for inorganic elements or Raman spectroscopy for organic compounds.

- Protocol: Isolate several particles from the process stream. For SEM-EDX, mount particles on a conductive adhesive and image under high vacuum. For Raman, place particles on a slide and acquire spectra, comparing results to reference databases [5].

Chemical Analysis (If required for structure elucidation):

- Method: Perform solubility tests in various media. If soluble, use LC-HRMS or GC-MS for identification.

- Protocol: Dissolve particles in a suitable solvent. For LC-HRMS, inject the sample onto a C18 column, elute with a water-acetonitrile gradient, and analyze with a high-resolution mass spectrometer for accurate mass determination [5].

Root Cause Identification & Corrective Action:

- Correlate analytical results (e.g., identification of stainless steel abrasion or a specific polymer) with the manufacturing step to pinpoint the source (e.g., failing pump seal, degraded single-use bag).

- Implement corrective and preventive actions (CAPA), such as replacing faulty equipment or revising procedures.

The following workflow visualizes the structured approach to troubleshooting particulate contamination:

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Low Product Titer in a Fed-Batch Fermentation

This guide helps diagnose issues leading to lower-than-expected product yield.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Confirm Data & Process Parameters:

- Verify the accuracy of all in-process control data (pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature, substrate feed rates). Check calibration records for probes.

Analyze Metabolic Performance:

- Method: Perform integrated metabolomics and metabolic flux analysis.

- Protocol: Take samples at different fermentation phases. Quench metabolism rapidly, extract intracellular metabolites, and analyze using LC-MS. Use the flux data to calculate metabolic rates through central carbon pathways like the pentose phosphate pathway [6].

Investigate Cell Culture Health:

- Check for signs of contamination (bacterial, fungal, viral).

- Measure viability and specific growth rate. A declining growth rate may indicate inhibitory by-product accumulation or nutrient limitation.

Evaluate Critical Process Parameters (CPPs):

- Scrutinize the dynamic control of CPPs. For example, suboptimal dissolved oxygen tension can cripple oxidative metabolism and lead to inefficient product synthesis.

Implement Advanced Process Control:

- Method: Deploy an AI-driven dynamic regulation system.

- Protocol: Develop a backpropagation neural network (BPNN) model using historical process data to capture non-linear correlations between substrate consumption, growth rates, and production rates. Use this model with a multi-objective optimization algorithm (e.g., NSGA-II) to adjust feeding strategies in real-time [6].

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance gains achievable with advanced dynamic control strategies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison: Traditional vs. AI-Driven Dynamic Regulation in Gentamicin C1a Fermentation [6]

| Performance Metric | Traditional Fed-Batch | AI-Driven Dynamic Regulation | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Final Titer (mg Lâ»Â¹) | Not Specified | 430.5 mg Lâ»Â¹ | 75.7% increase |

| Product Yield (mg gâ»Â¹) | Not Specified | 10.3 mg gâ»Â¹ | Highest reported |

| Specific Productivity (mg gDCWâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹) | Not Specifiable | 0.079 mg gDCWâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ | Highest reported |

| Model Accuracy (R² values) | N/A | 0.9631, 0.9578, 0.9689 | High predictive power |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing an AI-Driven Dynamic Control Framework for Fermentation

This protocol details the setup of a closed-loop control system for enhancing process robustness and productivity.

1. Objective: To create a real-time, AI-driven control system that dynamically adjusts nutrient feeding to resolve phase-specific metabolic trade-offs and maximize the titer of a target secondary metabolite.

2. Research Reagent Solutions & Key Materials:

Table 2: Essential Materials for AI-Driven Fermentation Optimization

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Dual-Spectroscopy Probes | Near-infrared (NIR) and Raman probes for real-time, in-line monitoring of key culture parameters [6]. |

| Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) Model | The core AI model that learns non-linear kinetics from process data to predict behavior [6]. |

| NSGA-II Algorithm | A multi-objective optimization algorithm used to find the best trade-offs between competing metabolic demands [6]. |

| Multi-modular Bioreactor System | A bioreactor equipped with automated pumps for carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen supplementation, integrated with real-time sensors [6]. |

3. Methodology:

Data Collection & Kinetic Modeling:

- Run initial fermentation batches to generate comprehensive data on substrate consumption, growth, and product formation.

- Train a BPNN model to accurately capture the non-linear correlations between specific substrate consumption rates, specific growth rates, and specific production rates. Target R² values >0.95 [6].

Multi-Objective Optimization:

- Define optimization objectives (e.g., maximize titer, minimize by-products). Use the NSGA-II algorithm with the trained BPNN to identify optimal feeding trajectories that balance these objectives [6].

System Integration & Closed-Loop Control:

- Integrate the NIR and Raman probes for real-time sensing.

- Implement the optimized feeding strategy in a closed-loop system, where the AI model uses real-time sensor data to dynamically adjust the nutrient feed pumps, coordinating carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen based on actual metabolic demands [6].

4. Expected Outcome: Significant enhancement in product titer and specific productivity, along with a dynamic reorganization of the metabolic network favoring product biosynthesis, as revealed by metabolomics and flux analysis [6].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected modules of this advanced control framework:

Protocol 2: Root Cause Analysis for Viral Contamination in a Cell Culture Process

1. Objective: To identify the source and implement corrective actions for a viral contamination event in a mammalian cell culture bioreactor.

2. Methodology:

Immediate Actions:

- Quarantine the affected bioreactor and all associated harvest materials.

- Notify quality assurance and begin a formal deviation investigation.

Sample Testing:

- Test the cell bank (Master and Working Cell Banks), raw materials (especially animal-derived components), and the harvest fluid using highly sensitive PCR-based assays.

Process Review:

- Audit all aseptic procedures during media preparation, inoculation, and sampling.

- Review sterilization records for filters, growth media, and bioreactor assembly.

- Check integrity testing data for all sterilizing-grade filters used for gases and liquids entering the bioreactor.

Viral Clearance Validation:

3. Expected Outcome: Identification of the most probable root cause (e.g., contaminated raw material, breach in aseptic technique) and implementation of CAPA to prevent recurrence, such as implementing more stringent raw material testing or operator re-training.

How Native Metabolic Regulation Limits Industrial Production

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my engineered microbial host show high initial product titers that rapidly decline during scale-up?

This is a classic symptom of native metabolic regulation reasserting control. Native hosts have evolved complex regulatory networks to maintain metabolic homeostasis, which often perceive high flux through engineered pathways as stressful or wasteful [10]. Key limitations include:

- Catabolite repression: Preferred carbon sources may inhibit synthetic pathway enzymes [10]

- Feedback inhibition: End products may inhibit key enzymes in both native and synthetic pathways [10]

- Resource competition: Synthetic pathways compete with essential metabolism for precursors, cofactors, and energy [11]

Q2: How can I prevent metabolic burden from collapsing my production system?

Metabolic burden occurs when synthetic pathways overwhelm native metabolic capacity [11]. Strategies include:

- Dynamic regulation: Implement biosensors that decouple growth from production phases [12]

- Coculture engineering: Distribute metabolic load between specialized strains [11]

- Phased nutrient feeding: Use different carbon sources sequenced to minimize competition [11]

Q3: What are the most common pathway bottlenecks in engineered systems?

Bottlenecks typically occur at points where synthetic and native metabolism intersect [10]:

- Cofactor imbalance: NADPH/NADP+, ATP/ADP ratios disrupted by heterologous enzymes

- Transport limitations: Intermediate metabolites not efficiently shuttled between compartments or cells

- Enzyme promiscuity: Non-specific activities divert carbon from target pathways [10]

Table 1: Common Metabolic Imbalances and Detection Methods

| Imbalance Type | Key Symptoms | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Cofactor depletion | Reduced growth rate, byproduct accumulation | Metabolomics, enzyme activity assays [10] |

| Metabolic crowding | Decreased native protein synthesis, stress response activation | Proteomics, transcriptomics [11] |

| Toxicity | Membrane damage, reduced viability | Cell staining, fermentation kinetics [10] |

| Energy deficit | Glycolytic flux increases, ATP-dependent processes slow | ATP/ADP measurements, metabolic flux analysis [6] |

Troubleshooting Guide for Native Regulation Conflicts

Problem: Inconsistent product yield between small and large-scale reactors

Root Cause: Native regulation responds differently to heterogeneous conditions in large reactors. Gradients in nutrients, oxygen, and pH trigger stress responses that inhibit production pathways [12].

Solutions:

- Implement real-time monitoring with biosensors for key metabolites [6]

- Develop AI-driven feeding strategies that anticipate metabolic shifts [6]

- Engineer strains with feedback-resistant enzymes to maintain flux under varying conditions [10]

Problem: Unstable coculture populations despite designed syntrophy

Root Cause: Competitive relationships emerge where one strain outcompetes others for shared resources, disrupting the optimal population ratio [11].

Solutions:

- Create nutritional interdependencies using knockout strains requiring metabolite exchange [11]

- Implement quorum-sensing systems to balance population dynamics [11]

- Use different carbon source preferences to minimize direct competition [11]

Table 2: Quantitative Assessment of Dynamic Regulation Strategies

| Strategy | Production Improvement | Implementation Complexity | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI-driven kinetic modeling | 75.7% titer increase [6] | High | R² values: 0.9631 consumption, 0.9578 growth, 0.9689 production [6] |

| Biosensor-mediated control | 2-5 fold range reported [12] | Medium | Dynamic range, response time, signal-to-noise ratio [12] |

| Cross-feeding cocultures | 38-fold rosmarinic acid increase [11] | Medium to High | Population stability, metabolite transfer efficiency [11] |

| Pathway compartmentalization | 14.4-fold riboflavin increase [11] | Medium | Intermediate channeling, reduced crosstalk [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dynamic Regulation Setup Using Biosensors

Purpose: Bypass native feedback inhibition in real-time

Materials:

- Engineered TF-based biosensor for target metabolite [12]

- Regulable promoter system (e.g., Tet-On, quorum-responsive)

- Real-time monitoring equipment (e.g., Raman spectroscopy, NIR) [6]

Methodology:

- Integrate metabolite biosensor with regulable promoter controlling rate-limiting enzyme

- Calibrate biosensor response curve to operating range matching inhibitor concentrations [12]

- Implement multi-objective optimization (e.g., NSGA-II) to resolve phase-specific trade-offs [6]

- Validate with integrated metabolomics and metabolic flux analysis [6]

Protocol 2: Stabilizing Artificial Coculture Systems

Purpose: Maintain optimal population ratios for distributed metabolic pathways

Materials:

- Specialized strains with complementary auxotrophies [11]

- Cross-feeding metabolites (amino acids, vitamins, ATP analogs) [11]

- Population monitoring system (e.g., flow cytometry, selective plating)

Methodology:

- Engineer cross-feeding interdependencies using nutrient-deficient and metabolite-overexpressing strains [11]

- Establish co-dependence by knocking out key biosynthetic genes in both strains [11]

- Optimize initial inoculation ratios through iterative batch experiments

- Implement adaptive laboratory evolution to enhance mutualistic interactions [11]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Overcoming Native Regulation

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription factor biosensors | Metabolite-responsive genetic regulation | Dynamic control, high-throughput screening [12] |

| Riboswitches | RNA-based metabolite sensing | Real-time metabolic flux regulation [12] |

| Orthogonal cofactor systems | Bypass native redox regulation | Reduce cofactor competition [10] |

| Two-component system engineering | Environmental signal transduction | Extracellular metabolite monitoring [12] |

| Antifouling coatings | Prevent reactor surface deposits | Maintain consistent heat transfer and reaction efficiency [13] |

| Scale inhibitors | Prevent precipitation of salts | Reduce reactor fouling in concentration processes [13] |

Metabolic Regulation Diagrams

Diagram 1: Native vs Engineered Metabolic Regulation

Diagram 2: AI-Driven Dynamic Regulation Framework

Two-Stage Processes, Decoupling Growth from Production, and Metabolic Deregulation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core advantage of using a two-stage process over a traditional one-stage fermentation? A two-stage process decouples the competing objectives of cell growth and product formation [14]. In the first stage, the process is optimized for rapid biomass accumulation. In the second stage, metabolic pathways are switched to maximize product synthesis, often during a nutrient-limited stationary phase [15] [14]. This separation can lead to significantly higher volumetric productivity and titers, as it avoids the metabolic trade-offs inherent in trying to grow and produce at the same time [14]. Furthermore, by deregulating metabolism in the production phase, the process can become more robust and easier to scale up, as the engineered cells have a limited ability to divert resources away from production in response to environmental fluctuations [15].

Q2: My production titer drops significantly when scaling from shake flasks to bioreactors. Could a two-stage dynamically controlled process help? Yes, this is a primary challenge that two-stage dynamic deregulation seeks to address. A lack of process robustness during scale-up is common because cells experience different and changing microenvironments (e.g., in nutrient levels, pH, oxygen) in larger reactors [15] [14]. Implementing a two-stage process with dynamic metabolic valves can make the production phase less sensitive to these variations. For example, studies producing citramalate and xylitol in E. coli reported successful initial scale-up to instrumented reactors without requiring traditional process optimization, achieving high titers of ~125 g/L and ~200 g/L, respectively [15]. The dynamic deregulation of central metabolic pathways was hypothesized to be key to this improved scalability [15].

Q3: What are "metabolic valves" and how are they implemented? Metabolic valves are genetic interventions that allow for the dynamic control of metabolic fluxes. They function by reducing the activity of key enzymes in central metabolism to deregulate innate metabolic control and redirect flux toward your product [15]. A common implementation method combines two techniques:

- Proteolysis: Appending a C-terminal degron tag (e.g., DAS+4) to a target protein, marking it for degradation [15].

- Gene Silencing: Using the CRISPR Cascade system to express silencing gRNAs that block transcription of target genes [15]. This combination has been shown to reduce enzyme levels (e.g., >95% reduction in Zwf, 80% reduction in GltA) effectively, unlocking higher production fluxes in the stationary phase [15].

Q4: How do I select which metabolic valve(s) to implement in my pathway? Valve selection can be guided by computational algorithms. One algorithm uses genome-scale models to identify reactions that, when used as switchable valves, can shift metabolism from a high-biomass yield state to a high-product yield state [14]. This approach has shown that a single switchable valve is sufficient for 56 out of 87 different organic products in E. coli, with key valves often found in glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation [14].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Scalability | Performance (titer/yield) drops during scale-up | Lack of process robustness; cells responding to microenvironment variations in large-scale bioreactors [15] | Implement a two-stage process with dynamic metabolic valves to deregulate central metabolism and reduce cellular adaptability to environmental changes [15] |

| Metabolic Burden & Stability | Reduced growth, genetic instability, or takeover by non-productive mutants | Metabolic burden from resource competition (ATP, cofactors, ribosomes); advantage for fast-growing, non-productive cells [14] | Use dynamic control to decouple growth from production. Employ a two-stage switch to minimize burden during growth phase [14] |

| Co-factor Imbalance | Sub-optimal yield due to insufficient NADPH/NADH availability | Native cofactor regeneration cannot meet pathway demands [15] | Implement valves that improve cofactor fluxes. Example: Reduce FabI activity to decrease fatty acid metabolite pools, alleviating inhibition of membrane-bound transhydrogenase and improving NADPH flux [15] |

| Substrate Uptake Inhibition | Low glucose uptake in production phase, limiting yield | Accumulation of metabolic intermediates (e.g., alpha-ketoglutarate) inhibiting transport systems [15] | Dynamically reduce citrate synthase (GltA) levels to lower alpha-ketoglutarate pools, alleviating inhibition of glucose uptake [15] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Two-Stage Dynamic Control Process

This protocol outlines the key steps for establishing a phosphate-limited two-stage process in E. coli with dynamic metabolic valves, based on methodologies that have successfully produced citramalate, xylitol, and alanine [15].

Stage 1: Growth Phase

- Objective: Maximize biomass accumulation.

- Medium: Use a growth medium with sufficient phosphate to support robust cell division.

- Process Conditions: Maintain optimal temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen for growth. No induction of the metabolic valves or production pathways is required at this stage.

- Endpoint: The transition to the second stage is triggered by the natural depletion of phosphate from the medium.

Stage 2: Production Phase

- Objective: Maximize product synthesis in a growth-arrested state.

- Induction: The depletion of phosphate serves as a natural inducer for the low-phosphate inducible promoter (e.g., the

yibDpromoter) [15]. This promoter drives the expression of:- The heterologous production pathway (e.g., L-alanine dehydrogenase).

- The components of the metabolic valve system (e.g., CRISPR Cascade and proteolysis tags).

- Metabolic Valve Operation: The induced system enacts metabolic deregulation via:

- Proteolysis: Degron-tagged native enzymes (e.g., Zwf, GltA, FabI) are degraded.

- Gene Silencing: gRNAs from the pCASCADE plasmid target and silence the corresponding genes.

- Process Control: Maintain carbon source feeding (e.g., glucose) and other non-limiting nutrient conditions to support continuous production during stationary phase.

The workflow is also summarized in the following diagram:

Key Metabolic Valves and Deregulation Mechanisms

The table below summarizes key metabolic valves that have been experimentally validated to enhance production by deregulating central metabolism in E. coli [15].

| Target Enzyme | Valve Action | Metabolic Consequence | Result for Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citrate Synthase (GltA) | >80% reduction in enzyme level | Reduces alpha-ketoglutarate pools, alleviating inhibition of glucose uptake | Increases carbon substrate uptake in stationary phase [15] |

| Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (Zwf) | >95% reduction in enzyme level | Reduces NADPH pools, activating SoxRS regulon & increasing pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase (YdbK) expression | Increases acetyl-CoA flux; enhanced NADPH flux via ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase [15] |

| Enoyl-ACP Reductase (FabI) | ~75% reduction in enzyme level | Decreases fatty acid metabolite pools, alleviating inhibition of membrane-bound transhydrogenase | Improves NADPH availability for NADPH-dependent biosynthetic pathways [15] |

| Transhydrogenase (UdhA) | ~30% reduction in enzyme level | Alters balance between NADH and NADPH cofactor pools | Can improve yield for pathways with specific cofactor demands [15] |

The interplay of these valves and their effects on central metabolism are visualized in the following pathway diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Key Specification / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate-Limited Medium | Triggers the transition from growth stage to production stage by depleting a key nutrient [15] | Ensure precise formulation to control the timing of the metabolic switch |

| Low Phosphate-Inducible Promoter (e.g., yibD) | Drives high-level expression of heterologous pathways and valve components specifically in the production phase [15] | Provides a strong, chemically inducible system without the need for external inducers like IPTG |

| C-terminal Degron Tag (DAS+4) | Appended to a target protein to mark it for proteolysis, dynamically reducing its concentration [15] | A key component of the metabolic valve for post-translational control of enzyme levels |

| CRISPR Cascade System & gRNAs (pCASCADE plasmid) | Provides gene silencing capability for metabolic valves, transcriptionally repressing target genes [15] | Enables multi-valve control; gRNAs are designed to target specific metabolic genes |

| Specialized Production Plasmid | Expresses the heterologous biosynthetic pathway for the target compound (e.g., L-alanine dehydrogenase) [15] | Should be compatible with the valve system plasmids and use the same inducible promoter |

| 2-Iodo-1,1'-binaphthalene | 2-Iodo-1,1'-binaphthalene | 2-Iodo-1,1'-binaphthalene is a key synthetic intermediate for chiral ligands. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. |

| 2-Oxetanone, 4-cyclohexyl- | 2-Oxetanone, 4-cyclohexyl-, CAS:132835-55-3, MF:C9H14O2, MW:154.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Product Yield in Batch Cultures

Problem: Engineered bacterial strains are consuming most of the substrate for biomass rather than the desired product, leading to low overall yield [16].

Explanation: In a one-stage bioprocess, there is a fundamental trade-off between cell growth (biomass accumulation) and product synthesis. Strains with very high growth rates tend to direct resources toward their own replication, wasting substrate [16]. Dynamic control strategies can decouple these competing objectives.

Solution: Implement a two-stage dynamic control strategy [14] [16].

- Design a genetic circuit that allows cells to first grow maximally to achieve a large population.

- Inhibit host metabolism after sufficient growth to redirect cellular resources and metabolic flux toward product synthesis [16].

- Use computational algorithms to identify key metabolic "valves" (reactions) in pathways like glycolysis or the TCA cycle that can be switched to shift from high biomass yield to high product yield [14].

Preventative Measures:

- Select strains with moderate growth rates but high synthesis rates for high-yield processes [16].

- For batch processes with limited nutrients, design circuits to reduce resource-intensive activities (like RNA polymerase expression) after growth to focus on production [14].

Guide 2: Managing Reactor Fouling and Catalyst Deactivation

Problem: Accumulation of unwanted materials on reactor surfaces and loss of catalyst activity are reducing heat transfer efficiency and reaction rates [13].

Explanation: Fouling can stem from chemical degradation, salt precipitation, or polymer deposition. Catalyst deactivation can occur via sintering (agglomeration at high temperatures), poisoning (impurities binding to active sites), or coking (carbon deposition) [13]. These issues directly impair the reactor's rate and efficiency.

Solution:

- For Fouling:

- For Catalyst Deactivation:

- Preventative: Purify the feed stream to remove poisons like sulfur and control the reactor temperature within the optimal range to prevent thermal degradation [13].

- Corrective: Regenerate deactivated catalysts using oxidative regeneration (burning off coke) or reductive regeneration (treating with hydrogen to remove poisons) [13].

Guide 3: Overcoming Temperature Control Issues in Exothermic Reactions

Problem: Inadequate temperature control leads to suboptimal reaction conditions, reduced yields, formation of by-products, and potential safety hazards like runaway reactions [13].

Explanation: Temperature variations are often caused by insufficient heat transfer due to fouling, malfunctioning sensors, or poor design of heating/cooling systems. Exothermic reactions can cause uncontrollable temperature rises if heat is not properly dissipated [13].

Solution:

- Ensure efficient heat transfer by regularly cleaning heat exchangers and reactor walls [13].

- Incorporate advanced control systems with real-time temperature sensors and feedback to automatically adjust heating and cooling rates [13].

- For exothermic reactions, use efficient cooling systems like external cooling jackets, internal cooling coils, or circulating reactants through heat exchangers [13].

- Implement robust safety features like emergency shutdown systems and pressure relief valves [13].

Guide 4: Optimizing Processes with Complex or Unknown Kinetics

Problem: Optimizing a reaction is slow, reagent-intensive, and difficult when the reaction mechanism is unknown or the kinetics are highly nonlinear [17].

Explanation: Traditional methods like design of experiments (DoE) struggle with complex, multivariable dynamics. Full kinetic characterization can be prohibitively time-consuming and expensive [18] [17].

Solution: Implement a Dynamic experiment Optimization (DynO) strategy using Bayesian optimization (BO) in a flow reactor [17].

- Set up an automated flow chemistry system (e.g., a tubular reactor).

- Use the DynO algorithm, which changes optimization parameters (e.g., residence time, reactant ratio, temperature) over time in a sinusoidal fashion, creating a dynamic trajectory through the design space [17].

- Allow the BO algorithm to use the rich data from these dynamic experiments to efficiently guide the search for optimal conditions, saving reagents and time compared to steady-state experiments [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental advantage of dynamic metabolic control over static control? Static control uses fixed, constitutive expression of pathways, which can lead to metabolic burden, resource competition, and accumulation of toxic intermediates. Dynamic control uses genetically encoded systems that allow cells to autonomously adjust their metabolic flux in response to their internal or external state. This enhances robustness, diverts resources more efficiently, and can lead to significant improvements in titer, rate, and yield (TRY) [14].

FAQ 2: When should I choose a two-stage bioprocess over a one-stage process? A two-stage process, which decouples growth from production, is particularly beneficial in batch processes where nutrients become limited. It allows cells to first build a large population before switching to a high-synthesis, low-growth state. However, if the production strain performs poorly under slow-growth conditions (e.g., has a very low glucose uptake rate in the production phase), a one-stage process in a constant-nutrient environment like a fed-batch reactor might be more productive [14].

FAQ 3: My data is noisy and limited. Can I still use machine learning for bioprocess optimization? Yes, data-driven approaches like machine learning (ML) can still provide value. For instance, random forest regression and support vector regression (SVR) have been used to predict key yield indicators like bioreactor final weight from historical batch records, even with limited datasets. However, with small data, results should be interpreted as an exploratory proof-of-concept. For better reliability, consider hybrid modeling frameworks that combine ML with mechanistic insights [18].

FAQ 4: How can I reduce the cost of expensive cofactors (e.g., ATP) in my enzymatic synthesis? A common strategy is to incorporate an additional enzyme to regenerate the cofactor. In continuous flow systems, you can co-immobilize the recycling enzyme with your primary enzymes on a solid support. This creates a self-sustaining system within the reactor, allowing you to use a substoichiometric amount of cofactor and significantly reducing costs [19].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Models for Yield Prediction

| Model Name | Target Metric | Performance (R²) | Key Influential Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Bioreactor Final Weight (BFW) | 0.978 [18] | Transfer timing, nutrient additions [18] |

| Random Forest Regression | Harvest Titer (HT) | Difficult to model with available data [18] | pH, glucose, lactate, viable cell density (VCD) [18] |

| Gradient Boosting Machine | Packed Cell Volume (PCV) | Difficult to model with available data [18] | Biomass capacitance, aeration conditions [18] |

Table 2: Key Design Principles for High Culture-Level Performance

| Target Metric | Desired Strain Phenotype | Recommended Enzyme Expression Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| High Yield | High synthesis, Low growth [16] | High expression of synthesis enzymes (Ep, Tp); Low expression of host enzyme (E) [16] |

| High Productivity | Lower synthesis, Higher growth [16] | Lower expression of synthesis enzymes (Ep, Tp); High expression of host enzyme (E) [16] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Two-Stage Dynamic Control Strategy in E. coli

Objective: To decouple growth and production phases to improve product yield in a batch culture.

Materials:

- Strain: E. coli strain engineered with a base production pathway.

- Genetic Circuit Components: Inducible promoter system (e.g., arabinose- or IPTG-inducible), genes for metabolic "valve" enzymes (e.g., from glycolysis or TCA cycle) [14].

- Media: Appropriate growth medium with inducers.

- Equipment: Bioreactor, spectrophotometer (for OD measurements), HPLC or GC (for product quantification).

Methodology:

- Circuit Design: Clone a genetic circuit where a key metabolic valve reaction (identified using algorithms like [14]) is placed under the control of an inducible promoter.

- Growth Phase: Inoculate the engineered strain into the bioreactor. Allow cells to grow under conditions where the inductor is absent or repressed, maximizing biomass accumulation.

- Production Phase Switch: At mid-to-late exponential growth phase (OD ~ 0.6-0.8), add the inducer to the culture. This should trigger the genetic circuit to inhibit host metabolism and activate the product synthesis pathway.

- Monitoring: Sample regularly to measure OD600 (cell density), substrate concentration, and product titer. Calculate the specific growth rate and product synthesis rate for each phase.

Protocol 2: Dynamic Experiment Optimization (DynO) for Reaction Screening

Objective: To rapidly optimize a chemical reaction with multiple continuous variables using Bayesian optimization and dynamic flow experiments.

Materials:

- Equipment: Tubular flow reactor (e.g., Plug Flow Reactor, PFR), automated pumps, in-line/on-line analyzer (e.g., IR, NMR), computer with DynO control software [17].

- Reagents: Reaction substrates and solvents.

Methodology:

- System Setup: Calibrate the flow reactor system and ensure the analytical method is configured for continuous data collection.

- Algorithm Configuration: Define the optimization parameters (e.g., residence time (Ï„), reactant ratio, temperature) and the objective function to maximize (e.g., yield).

- Initialization: Establish a steady state at an initial set of conditions.

- Dynamic Experimentation: Initiate the DynO algorithm. It will create sinusoidal variations of the parameters over time according to the equation [17]:

X_I(t) = X_0 * (1 + δ * sin(2πt / T + φ))The algorithm uses Bayesian optimization to guide these trajectories toward more optimal regions of the design space. - Data Collection & Reconstruction: Collect the outlet data (objective Y(t)) and reconstruct the parameters (X_R) that produced it, accounting for the residence time delay in the reactor [17].

- Termination: Run the optimization until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., reagent budget, convergence).

Workflow and System Diagrams

DynO Optimization Workflow

Two-Stage Dynamic Control Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Dynamic Control and Bioprocess Optimization

| Item Name or Category | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Inducible Promoter Systems | Genetically encoded actuators (e.g., arabinose- or IPTG-inducible) that allow external control over the timing of gene expression for metabolic valves [14]. |

| Biosensors | Genetically encoded sensors that detect internal metabolic states (e.g., nutrient levels, metabolite concentrations) and trigger actuator responses for autonomous dynamic control [14]. |

| Enzyme Immobilization Supports | Solid supports (e.g., polymer-based resins, magnetic beads) for covalent attachment or affinity binding of enzymes. Enable enzyme recycling, increased stability, and use in packed bed reactors for continuous flow biocatalysis [19]. |

| Sugar Nucleotides | Activated sugar donors (e.g., UDP-Glc, GDP-Man) that are cornerstone building blocks for the enzymatic synthesis of glycans and other complex molecules [19]. |

| Cofactor Recycling Systems | Enzyme pairs (e.g., for NADH/ATP regeneration) that work together to regenerate expensive cofactors using inexpensive precursors, making biocatalytic processes more economically feasible [19]. |

| Dodeca-4,11-dien-1-ol | |

| 3-Cyclopropyl-1H-indene | 3-Cyclopropyl-1H-indene |

Implementing Dynamic Control: Strategies, Tools, and Real-World Applications

Engineered Genetic Circuits and Synthetic Metabolic Valves for Dynamic Regulation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the main advantages of using dynamic regulation over static control in metabolic engineering?

Dynamic regulation allows engineered microbes to autonomously adjust their metabolic flux in response to their internal metabolic state or external environment. This leads to improved titer, rate, and yield (TRY) metrics by enabling real-time optimization, reducing metabolic burden, and making strains more robust to changing fermentation conditions. In contrast, static control, which uses constitutive promoters and fixed genetic parts, cannot respond to such changes and often creates detrimental metabolic imbalances [20] [14].

FAQ 2: My microbial production host is experiencing slow growth or low productivity. What could be the cause?

This is a common symptom of metabolic burden, where the synthetic circuit consumes excessive cellular resources (e.g., ribosomes, energy, precursors), hindering host cell growth. It can also stem from the accumulation of toxic intermediates or an imbalanced carbon flux distribution where the synthetic pathway starves essential central metabolic pathways of necessary precursors [20] [21]. Implementing dynamic control can help alleviate this by decoupling growth and production phases.

FAQ 3: How can I make my synthetic gene circuit more stable over many generations?

Evolutionary degradation is a major challenge. Strategies include:

- Implementing Negative Feedback: Controllers that sense and regulate their own output can reduce burden and slow the takeover of non-producing mutant cells [21].

- Using Post-Transcriptional Control: Small RNA (sRNA)-based controllers can offer more robust performance than transcriptional control [21].

- Coupling to Essential Genes: Linking circuit function to an essential gene for survival can reduce the selective advantage of mutants [21].

FAQ 4: What is a "synthetic metabolic valve" and how does it work?

A synthetic metabolic valve is a genetic tool that dynamically controls the flow of carbon through a metabolic pathway. It functions by regulating key enzymatic steps (e.g., in glycolysis or the TCA cycle) [14]. This can be achieved using tunable 3'-UTR terminators to control transcription levels [22] or biosensor-based circuits that adjust gene expression in response to metabolite levels [20] [23]. Valves are crucial for optimally distributing metabolic flux between endogenous pathways (for growth) and heterologous pathways (for production) [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Low Product Yield

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Titer/Unbalanced Precursors | Competition for carbon flux between synthetic pathway and central metabolism, or between different branches of the synthetic pathway [20]. | Implement a bifunctional dynamic control network. Use a metabolite-responsive biosensor (e.g., salicylate-sensing) to dynamically regulate the supply of multiple precursors (e.g., malonyl-CoA and salicylate) [20]. |

| Loss of Production Over Time | Evolutionary instability. Non-producing mutants, which grow faster, outcompete the productive engineered cells [21]. | Design genetic circuits with negative autoregulation or growth-based feedback controllers. This reduces burden and extends functional half-life [21]. |

| High Metabolic Burden | Static overexpression of heterologous enzymes drains cellular resources, slowing growth and ultimately limiting production [20] [14]. | Adopt a two-stage fermentation process. Decouple growth from production. In the first stage, maximize cell growth with the production pathway off. In the second stage, activate production while minimizing growth [14]. |

| Inefficient Metabolic Flux | Suboptimal partitioning of carbon flux at a critical metabolic branch point [22]. | Install synthetic metabolic valves using a library of well-characterized 3'-UTR terminators with varying strengths to fine-tune the expression of key pathway genes without inducers [22]. |

Troubleshooting Experimental Workflows

Problem: Few or No Colonies After Transformation (Cloning)

- Cause: Inefficient ligation, incorrect heat-shock protocol, or the DNA construct may be toxic to the cells [24].

- Solution:

- Always run proper controls (e.g., uncut vector, cut vector) to diagnose the issue [24].

- Use high-efficiency competent cells.

- If the DNA is toxic, use a tightly regulated strain (e.g., NEB 5-alpha F´ Iq) and incubate at a lower temperature (25–30°C) [24].

- Clean up the ligation mix to remove contaminants like salts or PEG if using electroporation [24].

Problem: Unexpected or Dim Fluorescent Signal from a Reporter/Biosensor

- Cause: The protocol may have failed, or the result could be biologically accurate (e.g., low protein expression) [25].

- Solution:

- Repeat the experiment to rule out simple human error.

- Include appropriate controls: A positive control (a known working system) confirms the protocol works. A negative control confirms signal specificity [25].

- Check reagents and equipment: Ensure antibodies and other reagents are stored correctly and have not degraded. Verify microscope settings [25].

- Change one variable at a time: Systematically test variables like fixation time, antibody concentration, or cell growth phase, documenting every change meticulously [25].

Experimental Protocols

Objective: To dynamically balance the carbon flux towards two precursors, salicylate and malonyl-CoA, for improved 4-hydroxycoumarin (4-HC) production in E. coli.

Key Reagents:

- Bacterial Strains: E. coli BW25113 containing F' from XL1-Blue.

- Media: Luria-Bertani (LB) medium for inoculation; production media as defined.

- Antibiotics: Ampicillin (100 μg/mL), Kanamycin (50 μg/mL), Chloramphenicol (30 μg/mL).

- Genetic Tools: Salicylate-responsive biosensor system, CRISPRi system for dynamic gene repression.

Methodology:

- Rewire Metabolic Background: Genetically engineer the host to be a high salicylate producer.

- Circuit Integration: Introduce the salicylate-responsive biosensor. This biosensor is designed to dynamically regulate the expression of genes involved in supplying malonyl-CoA and salicylate.

- CRISPRi Integration: Couple the biosensor to a CRISPRi system to dynamically repress key genes in the 4-HC biosynthetic pathway.

- Cultivation & Analysis:

- Inoculate engineered strains in appropriate media with antibiotics.

- Culture aerobically in a rotary shaker at 37°C.

- Monitor cell density (OD600) and harvest samples for product quantification via HPLC or LC-MS.

- Use transcriptomic analysis to confirm the regulatory impact of the circuit.

Objective: To control metabolic fluxes in branched pathways by fine-tuning gene expression using a library of 3'-untranslated region (3'-UTR) terminators.

Key Reagents:

- Bacterial Strains: E. coli K-12 MG1655 and derivative strains (e.g., ΔpfkA Δzwf double-knockout).

- Media: M9 minimal medium with carbon source (e.g., glucose, glycerol).

- Genetic Tools: Plasmid vectors, library of 3'-UTR parts with characterized termination strength.

Methodology:

- Terminator Library Construction: Use techniques like Term-Seq to identify and characterize a wide range of native 3'-UTRs with varying termination strengths [22].

- Valve Integration: Clone selected 3'-UTR terminators downstream of the key genes you wish to control in your metabolic pathway of interest.

- Screening and Validation:

- Transform the constructed plasmids into your production host.

- Culture strains in M9 medium under production conditions (e.g., in a rotary shaker at 37°C for 24-48 hours).

- Measure final product titer (e.g., 2,3-butanediol or myo-inositol) and cell density (OD600).

- Compare the performance of different 3'-UTR valves to identify the optimal flux balance for maximum yield.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Dynamic Regulation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolite-Responsive Biosensors [20] [14] | Sense intracellular metabolite levels and transduce this signal into a genetic output. | A salicylate biosensor used to dynamically regulate precursor supply [20]. |

| CRISPRi System [20] | Provides a programmable actuator for precisely repressing target genes. | Coupled to a biosensor to downregulate a competing pathway when a metabolite accumulates [20]. |

| Tunable 3'-UTR Terminators [22] | Fine-tune gene expression at the transcriptional level by controlling transcription termination efficiency. | Used as "metabolic valves" to optimally balance flux between heterologous and native pathways [22]. |

| Small RNA (sRNA) Controllers [21] | Enable post-transcriptional regulation for fast and efficient gene silencing. | Used in negative feedback loops to reduce circuit burden and improve evolutionary stability [21]. |

| Two-Stage Fermentation Switch [14] | Decouples cell growth from product formation to maximize overall productivity. | Using a genetic switch to halt growth and activate production after a high cell density is reached [14]. |

| 2,2'-Diethyl-3,3'-bioxolane | 2,2'-Diethyl-3,3'-bioxolane | 2,2'-Diethyl-3,3'-bioxolane is for research use only (RUO). It is a high-purity chemical for applications in organic synthesis and as a specialty solvent. Not for human consumption. |

| 1-Iodonona-1,3-diene | 1-Iodonona-1,3-diene, CAS:169339-71-3, MF:C9H15I, MW:250.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is biosensor-driven feedback control and why is it important in metabolic engineering? Biosensor-driven feedback control is a synthetic biology strategy where a genetically encoded biosensor detects a specific metabolite or product and automatically regulates gene expression to optimize production. This is crucial because it allows microbial cell factories to autonomously balance cell growth and product formation, prevent the accumulation of toxic intermediates, and maximize titers, rates, and yields (TRY) without manual intervention [26] [14]. This approach addresses key challenges in metabolic engineering, including metabolic burden, carbon flux imbalance, and culture heterogeneity [14].

Q2: What types of biosensors are commonly used in dynamic control systems? The most common types used in dynamic control are:

- Transcriptional Factor (TF)-based Biosensors: These utilize proteins that change conformation upon binding a target molecule (ligand), subsequently activating or repressing promoter activity to control downstream gene expression [26] [27].

- Nucleic Acid-based Biosensors: These include riboswitches and ribozymes—RNA elements that alter their structure in response to a ligand, thereby regulating transcription, translation, or mRNA stability [27].

- Quorum Sensing (QS) Systems: These biosensors respond to population density by detecting extracellular signaling molecules (e.g., AHL), enabling coordinated timing of gene expression across a cell population [27].

Q3: My production titer is low despite high cell density. Could this be a dynamic control issue? Yes, this is a classic symptom of a suboptimal metabolic balance. If biosynthetic pathways are expressed constitutively, they can create a significant metabolic burden during the growth phase, diverting resources away from biomass accumulation and ultimately limiting production. Implementing a two-stage dynamic control strategy can resolve this. In the first stage, cell growth is prioritized with minimal pathway expression. In the second stage, a biosensor triggers a switch to maximize production, often while reducing growth [14]. For example, a Quorum Sensing system can be used to delay production until a high cell density is achieved [27].

Q4: How can I quickly identify high-producing enzyme variants from a large library? Biosensors are ideal for high-throughput screening. By linking a biosensor that responds to your target product to a measurable output (like fluorescence), you can rapidly screen vast mutant libraries. Individual clones that produce more of the target metabolite will generate a stronger signal, allowing you to isolate the best performers without time-consuming analytical chemistry [26] [27]. For instance, a mevalonate-responsive biosensor was engineered to screen for optimal HMG-CoA reductase expression, leading to improved mevalonate yields [26].

Q5: My biosensor's dynamic range is too narrow for my application. What can I do? Narrow dynamic range is a common challenge that can be addressed through biosensor engineering. Key strategies include:

- Directed Evolution: Create mutant libraries of the sensor's ligand-binding domain and screen for variants with improved sensitivity and a wider response range [26] [27].

- Promoter Engineering: Modify the corresponding promoter sequence to fine-tune the level of gene expression upon activation or repression [27].

- Component Tuning: Adjust the expression levels of the biosensor components themselves (e.g., the TF) to alter the system's response curve [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Unstable Production in Fed-Batch Bioreactors

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Case Study Example |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Burden from constitutive expression of heterologous pathways. | Implement a metabolite-responsive biosensor for dynamic control. The biosensor should upregulate pathway enzymes only when a key precursor is abundant. | A muconic acid (MA)-responsive CatR biosensor was used to activate the MA synthesis pathway while repressing central metabolic genes via CRISPRi, stabilizing production and achieving 1.8 g/L [27]. |

| Toxic Intermediate Accumulation | Design a circuit where a biosensor responsive to the toxic compound represses its own synthesis pathway and/or activates a detoxification route. | In glucaric acid production, a myo-inositol (MI)-responsive IpsA biosensor was layered with a Quorum Sensing system to dynamically induce pathway genes only after sufficient biomass was achieved, preventing toxicity and improving yield [27]. |

| Culture Heterogeneity leading to non-producing subpopulations. | Use a Quorum Sensing (QS) circuit to couple production with population density, ensuring coordinated behavior. | The EsaI/EsaR QS system was used to switch off a competitive pathway (Pfk-1) at high cell density, redirecting flux to glucaric acid production and increasing the titer from unmeasurable to over 0.8 g/L [27]. |

Problem 2: Poor Biosensor Performance

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Case Study Example |

|---|---|---|

| Low Sensitivity (does not respond to physiological metabolite levels). | Engineer the biosensor's ligand-binding domain via saturation mutagenesis to improve its affinity for the target molecule. | The HucR biosensor, native to uric acid, was engineered through saturation mutagenesis to create variants that respond to ferulic acid and vanillin, enabling their dynamic overproduction [27]. |

| Lack of a Natural Biosensor for your target molecule. | 1. Construction of auxotrophic strains: Create a strain that requires the metabolite for survival and use growth as a readout [26].2. Repurpose existing TFs: Modify the specificity of a well-characterized TF (e.g., AraC) to recognize your new target [26]. | An E. coli mevalonate auxotroph was created by introducing a heterologous MVA pathway and disrupting the native MEP pathway. This strain's survival depended on mevalonate, effectively functioning as a biosensor [26]. |

| Cross-Talk or Lack of Specificity leading to false positives. | Implement logic gates in your genetic circuit. An AND gate, for example, can require two distinct signals (e.g., a metabolite AND a specific population density) to be present before activating production, greatly enhancing specificity [28]. | In cellular therapies, logic gates such as AND, N-IMPLY, and XOR have been engineered to ensure that therapeutic effector proteins are only delivered when multiple disease biomarkers are present, minimizing off-target effects [28]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: Implementing a Two-Stage Dynamic Control System Using Quorum Sensing

Objective: Decouple cell growth from product synthesis to enhance overall titer and productivity [14] [27].

Materials:

- Plasmid System: Contains the EsaI/EsaR QS module (EsaI produces AHL; EsaR is the AHL-responsive TF).

- Production Pathway: Your target biosynthetic pathway under the control of the AHL-repressible promoter PesaS.

- Competing Pathway Gene: A gene from a competing metabolic pathway (e.g., pfkA from glycolysis) under the control of PesaS.

Methodology:

- Strain Construction: Clone your production pathway genes and the competing pathway gene(s) into separate vectors, ensuring they are downstream of the PesaS promoter.

- Transformation: Co-transform the production strain with the QS plasmid and the pathway plasmids.

- Fermentation:

- Stage 1 (Growth): Inoculate the bioreactor. During early exponential phase, AHL concentration is low. EsaR represses PesaS, silencing the production pathway and the knocked-down competing pathway. This minimizes metabolic burden, allowing for rapid biomass accumulation.

- Stage 2 (Production): As cell density increases, AHL synthesized by EsaI accumulates. AHL binds to EsaR, relieving the repression of PesaS. This activates the expression of your production pathway while simultaneously down-regulating the competing pathway (e.g., PfkA), redirecting carbon flux toward the desired product [27].

- Monitoring: Track cell density (OD600), AHL concentration (e.g., via reporter assays), and product titer over time.

Diagram: Two-Stage Quorum Sensing Control Circuit

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening of Enzyme Variants Using a Metabolite-Responsive Biosensor

Objective: Identify enzyme mutants that confer the highest product yield from a large, diverse library [26] [27].

Materials:

- Biosensor Strain: A host strain containing a biosensor where a promoter, responsive to your target product, drives the expression of a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP).

- Mutant Library: A plasmid library of variant genes for a key enzyme in your biosynthetic pathway.

Methodology:

- Library Transformation: Transform the mutant library into the biosensor strain.

- Cultivation and Sorting: Grow the transformed library in microtiter plates or liquid culture under production conditions.

- Flow Cytometry: Use a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) to isolate the top 0.1-1% of cells displaying the highest fluorescence intensity. This high fluorescence indicates that these cells are producing the most target product, which activates the biosensor and GFP expression most strongly.

- Validation and Re-screening: Plate the sorted cells, allow them to grow, and repeat the sorting process 1-2 times to enrich the population for the best producers. Isolate individual clones and validate product titers using standard analytical methods (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS).

Diagram: High-Throughput Screening Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for Building Biosensor-Driven Control Systems

| Research Reagent | Function & Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Factors (TFs) | The core sensing element. Binds a specific metabolite, leading to conformational change and altered gene regulation (e.g., FdeR for naringenin, CatR for muconic acid) [26] [27]. | High specificity for ligand, tunable sensitivity via engineering. |

| Riboswitches/Ribozymes | Nucleic acid-based sensors (e.g., glmS ribozyme). Regulate at the RNA level in response to metabolites, offering fast response times [27]. | Small genetic footprint, function in cis without need for additional protein components. |

| Quorum Sensing Systems | Population-density sensors (e.g., LuxI/LuxR, EsaI/EsaR). Enable coordinated, time-delayed gene expression in a bioreactor [27]. | Synthase (LuxI/EsaI) produces AHL signal; Regulator (LuxR/EsaR) responds to AHL. |

| CRISPRi/a Modules | Powerful actuators for dynamic regulation. Allows multiplexed repression (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) of genes when guided by a biosensor [26] [27]. | Highly programmable; can target multiple genes simultaneously with minimal metabolic burden. |

| Reporter Proteins | Readable output for biosensor characterization and screening (e.g., GFP, mCherry for fluorescence). Essential for quantifying biosensor performance and HTP screening [26]. | Easily measurable, non-toxic, and stable. |

| Engineered Promoters | The interface between the sensor and the actuator. Contain specific operator sites for TF binding (e.g., PfdeO, PluxI) [27]. | Strength and leakiness can be engineered for optimal dynamic range. |

| N-bromobenzenesulfonamide | N-Bromobenzenesulfonamide|High-Purity|RUO | |

| Methanol;nickel | Methanol;nickel Research Catalyst | Methanol;nickel catalyst for alcohol electro-oxidation and fuel cell research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for personal use. |

Model-based control represents a paradigm shift in bioprocessing, moving from empirical quality-by-testing to a systematic Quality by Design (QbD) approach. This framework integrates quality directly into process design and control, enabled by rigorous mathematical models that predict system behavior. For researchers and scientists developing biosynthetic reactors, these control strategies are essential for navigating the inherent complexity of biological systems, where competition for cellular resources, metabolic burden, and metabolite toxicity can constrain performance [14].

The core challenge in dynamic control of biosynthetic reactors lies in forcing engineered microbes to maintain stable, high-level production at industrial scales. Dynamic metabolic engineering addresses this through genetically encoded control systems that allow microbes to autonomously adjust metabolic flux in response to their external environment and internal metabolic state [14]. This stands in contrast to traditional static control, where metabolic pathways are expressed constitutively with fixed expression levels. The implementation of model-based control is further transformed by Industry 4.0 technologies including Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), and Digital Twins (DTs), which enable real-time data analysis, predictive modeling, and process optimization [29].

Theoretical Foundations of Optimal Control

Optimal control theory provides the mathematical foundation for determining control policies that achieve specific bioprocess objectives while satisfying system constraints. For bioprocesses, this typically means maximizing titer, rate, and yield (TRY) metrics – the key performance indicators for commercial viability [14].

Fundamental Principles

At its core, optimal control in bioprocesses involves manipulating system inputs to optimize a defined performance index over time. Pontryagin's Maximum Principle (PMP) provides the necessary conditions for optimality, offering a geometric interpretation of optimal trajectories [30]. The principle is particularly valuable for solving complex bioprocess optimization problems where biological constraints must be respected.

Control Strategy Implementation

The table below summarizes the primary control strategies employed in model-based bioprocess control:

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Control Strategies for Bioprocesses

| Control Strategy | Key Mechanism | Typical Applications | Key Advantages | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Stage Control [14] | Decouples growth and production phases | Batch processes; products with high metabolic burden | Overcomes trade-offs between biomass accumulation and product formation | Reduced substrate uptake in stationary phase can limit production |

| Continuous Metabolic Control [14] | Autonomous, real-time flux adjustments in response to metabolites | Fed-batch and continuous bioprocesses | Maintains optimal metabolic state continuously; handles perturbations | Requires robust biosensors and complex genetic circuit design |

| Population Behavior Control [14] | Coordinates behavior across cell population | Processes prone to population heterogeneity | Prevents takeover by non-productive mutants; improves culture stability | Implementation complexity at large scales |

| Passive Reactor Control [31] | Relies on inherent negative reactivity feedbacks | Nuclear reactor systems with stable feedback | Simplicity; no dedicated controller needed | Effectiveness diminishes over reactor lifetime |

| Active Reactor Control [31] | Dedicated controller regulates key process variables | Systems requiring precise control throughout lifetime | Consistent performance regardless of system age | Requires sophisticated control system design |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Experimental Implementation

Model Selection and Development

Question: What criteria should I consider when selecting or developing a bioprocess model for control applications?

Answer: Choosing an appropriate model requires balancing multiple engineering and biological considerations: