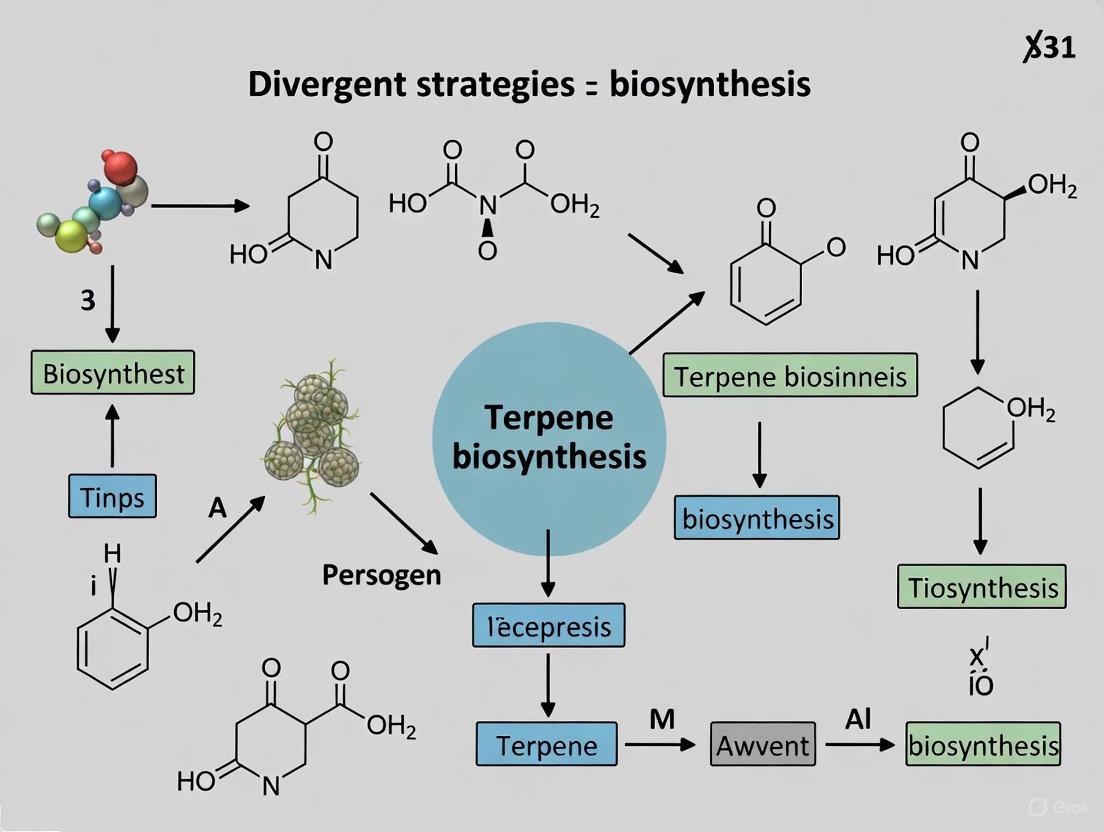

Divergent Strategies in Terpene Biosynthesis: From Natural Pathways to Engineered Cell Factories

This article synthesizes current knowledge on the divergent strategies underpinning terpene biosynthesis, the largest class of natural products.

Divergent Strategies in Terpene Biosynthesis: From Natural Pathways to Engineered Cell Factories

Abstract

This article synthesizes current knowledge on the divergent strategies underpinning terpene biosynthesis, the largest class of natural products. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of the mevalonate (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways, the enzymatic gatekeepers responsible for structural diversity, and the evolutionary drivers of this complexity. The review further delves into methodological advances in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology that harness these strategies for industrial and pharmaceutical applications. It addresses key challenges in pathway optimization and scaling, provides a comparative analysis of biosynthetic efficiency across biological systems, and concludes with future directions for leveraging these divergent strategies in sustainable drug discovery and bio-production.

The Evolutionary and Biochemical Roots of Terpene Diversity

Terpenoids, constituting the largest class of natural products with over 95,000 identified structures, perform essential functions across all life domains, ranging from primary metabolism to specialized ecological interactions [1] [2] [3]. Despite their remarkable structural diversity, all terpenoids originate from two universal five-carbon building blocks: isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) [4] [5] [6]. The fundamental paradigm in terpenoid biosynthesis revolves around two evolutionarily distinct pathways that generate these precursors: the mevalonate (MVA) pathway and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway [5] [6].

The evolutionary distribution of these pathways reveals a fascinating divergence in metabolic strategy. The MVA pathway is predominantly found in archaea, fungi, animals, and the cytosol of plants, while the MEP pathway operates in most bacteria, cyanobacteria, and plant plastids [7] [5] [6]. This compartmentalization is particularly sophisticated in plants, which have retained both pathways, enabling precise spatial and temporal control over terpenoid production [4] [6]. The existence of these parallel biosynthetic routes represents nature's solution to producing essential compounds under varying physiological conditions and environmental challenges.

Understanding the intricate relationship between these pathways—their distinct biochemical features, regulatory mechanisms, and metabolic cross-talk—provides critical insights for drug discovery, metabolic engineering, and unraveling the evolutionary adaptations that have shaped terpenoid diversity.

Core Pathway Biochemistry and Compartmentalization

The Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway

The MVA pathway represents a specialized metabolic network primarily localized to the cytoplasm and endoplasmic reticulum in eukaryotic cells, with potential contributions from peroxisomes [4]. This pathway orchestrates IPP biosynthesis through a six-enzyme cascade that consumes three acetyl-CoA molecules, three ATP equivalents, and two NADPH molecules per IPP molecule produced [4].

Key Enzymatic Steps:

- Initial Condensation: Two acetyl-CoA molecules condense to form acetoacetyl-CoA, catalyzed by acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase (AACT).

- HMG-CoA Formation: A third acetyl-CoA is added by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase (HMGS) to form 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA).

- Rate-Limiting Reduction: HMG-CoA is reduced to mevalonate by HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR), consuming two NADPH molecules. This committed step serves as the pathway's primary regulatory node [4] [8].

- Phosphorylation and Decarboxylation: Mevalonate undergoes two consecutive phosphorylations catalyzed by mevalonate kinase (MVK) and phosphomevalonate kinase (PMK), followed by an ATP-dependent decarboxylation by mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase (MPD) to yield IPP [9] [5].

- Isomerization: IPP is reversibly isomerized to DMAPP by IPP isomerase (IDI) [4].

The MVA pathway primarily supplies precursors for cytosolic terpenoid biosynthesis, including sesquiterpenes (C15), triterpenes (C30), and sterols like cholesterol [6] [8].

The Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathway

The MEP pathway operates exclusively within plastids in plants and is widespread among eubacteria [4] [7]. This pathway converts pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) into IPP and DMAPP through seven enzymatic reactions, consuming three ATP and three NADPH molecules [4] [7].

Key Enzymatic Steps:

- Initial Condensation: 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS) catalyzes the TPP-dependent condensation of pyruvate and GAP to form 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate (DXP). This represents a key flux-controlling step [4] [5] [8].

- Reductoisomerization: DXP reductoisomerase (DXR/IspC) converts DXP to MEP, the pathway's namesake intermediate.

- Nucleotide Attachment and Cyclization: Subsequent steps involving IspD, IspE, and IspF enzymes add a cytidine moiety, phosphorylate the intermediate, and catalyze cyclization to form 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate (MEcPP) [1] [5].

- Fe-S Cluster-Mediated Steps: IspG and IspH, both iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster enzymes, catalyze the reductive dehydration of MEcPP to HMBPP and its subsequent conversion to a mixture of IPP and DMAPP, respectively [7] [5]. The oxygen sensitivity of these Fe-S cluster enzymes positions the MEP pathway as an oxidative stress sensor [7].

The MEP pathway provides precursors for plastidial terpenoids, including monoterpenes (C10), diterpenes (C20), carotenoids (C40), and the side chains of chlorophylls and plastoquinones [4] [6].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of MVA and MEP Pathways

| Feature | Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway | Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Localization | Cytosol, ER, peroxisomes [4] | Plastids (plants), bacterial cytosol [4] [7] |

| Initial Substrates | Acetyl-CoA (3 molecules) [4] [9] | Pyruvate + Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate [4] [7] |

| Key Intermediates | HMG-CoA, Mevalonate [4] [5] | DXP, MEP, MEcPP [1] [5] |

| Energy Cofactors | 3 ATP, 2 NADPH per IPP [4] | 3 ATP, 3 NADPH per IPP/DMAPP [4] [7] |

| Metal Cofactors | Not typically required | Fe-S clusters (IspG, IspH); Mn²âº/Mg²⺠(DXR) [7] |

| Signature Enzymes | HMGR (rate-limiting) [4] [8] | DXS (flux-controlling), IspG, IspH (Fe-S cluster) [4] [7] |

| Primary Products | IPP (converted to DMAPP via IDI) [5] | IPP and DMAPP directly [5] |

| Pathway Essentiality | Essential in fungi, animals [5] | Essential in most bacteria, apicomplexan parasites [7] [5] |

Compartmentalization and Metabolic Cross-Talk

Plants exemplify the sophisticated compartmentalization of terpenoid biosynthesis, with the MVA and MEP pathways operating independently in distinct subcellular locations [6]. This spatial separation allows for independent regulation and facilitates the production of different terpenoid classes from distinct precursor pools [4] [6].

Despite this compartmentalization, substantial evidence indicates metabolic cross-talk between the pathways. Mutant analyses, chemical inhibitor studies, and isotopic labeling experiments have demonstrated the exchange of intermediates between plastids and the cytoplasm [4] [6]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and mass spectrometry studies have confirmed the formation of terpenoid compounds with mixed MVA/MEP origins, indicating limited but regulated metabolic flux between these compartments [4] [6]. The transporter facilitating IPP/DMAPP exchange across the plastid envelope, however, remains unidentified and represents a significant gap in our understanding [6] [8].

Figure 1: Compartmentalization of Terpenoid Biosynthesis in Plants. The MVA pathway in the cytosol and the MEP pathway in the plastid generate separate IPP/DMAPP pools for different classes of terpenoids. Dashed arrows indicate hypothesized cross-talk via unidentified transporters.

Regulatory Mechanisms and Environmental Interactions

Multi-Layered Pathway Regulation

The MVA and MEP pathways are subject to complex, multi-layered regulation that balances carbon allocation, energy consumption, and end-product synthesis [6]. Feedback inhibition serves as a critical regulatory mechanism, particularly in the MVA pathway where sterols inhibit HMGR activity, the pathway's rate-limiting enzyme [6] [8]. In the MEP pathway, the iron-sulfur cluster enzymes IspG and IspH are not only sensitive to oxygen but also position the pathway as an oxidative stress sensor and response system [7].

Hormonal and Environmental Regulation: Plant hormones, particularly jasmonates, activate terpenoid biosynthetic genes, enhancing the production of specialized metabolites for defense [8]. Light conditions profoundly influence pathway activity; the MEP pathway shows heightened activity under light, supporting photosynthesis-related isoprenoid synthesis, while the MVA pathway becomes more active in darkness, promoting phytosterol biosynthesis [4].

Epigenetic and Post-Translational Control: DNA methylation and histone modifications can silence or activate terpenoid biosynthetic gene clusters [8]. Additionally, post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation regulate enzyme activity, as demonstrated by the blue-light receptor AaCRY1 phosphorylating and activating AaDXS in Artemisia annua, thereby enhancing artemisinin precursor synthesis [8].

The MEP Pathway as an Oxidative Stress Sensor

The MEP pathway plays a nuanced role in oxidative stress responses beyond its metabolic function [7]. The terminal enzymes IspG and IspH contain oxygen-sensitive 4Fe-4S clusters that can be damaged under oxidative conditions, leading to the accumulation of the intermediate MEcPP [1] [7]. MEcPP functions as a retrograde signaling molecule in plastids, communicating the organellar status to the nucleus and activating stress-responsive genes [7]. This dual function of the MEP pathway—both producing essential isoprenoid antioxidants and directly participating in stress signaling—exemplifies the metabolic integration of biosynthesis and stress response [7].

Experimental Methodologies for Pathway Analysis

Genetic and Molecular Techniques

Gene Knockout and Functional Analysis: Essentiality of the MEP and MVA pathways can be determined through systematic gene knockouts. In Mycobacterium marinum, for instance, CRISPR-based tools or ORBIT (Operator-Based Repression with Induction and Titration) enable precise gene replacement and repression to demonstrate that the MEP pathway is essential while the MEV pathway is dispensable in culture but provides metabolic flexibility under stress [1].

Heterologous Expression and Pathway Reconstitution: Expressing putative terpene biosynthetic genes in model microorganisms like Escherichia coli or Saccharomyces cerevisiae allows for functional characterization of enzymes and reconstruction of entire pathways [9] [10] [3]. This approach is fundamental for verifying gene function and engineering production platforms.

Gene Expression Profiling: Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) are used to analyze transcript levels of MVA and MEP pathway genes under different conditions, such as stress treatments, developmental stages, or in response to hormone elicitors like jasmonate [8].

Metabolic Profiling and Flux Analysis

Metabolite Profiling: Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) enable quantification of pathway intermediates and end products. In M. marinum, metabolite profiling revealed that modulation of the MEV pathway causes compensatory changes in the concentration of MEP intermediates DOXP and CDP-ME, indicating functional interaction between the pathways [1].

Isotopic Labeling: Feeding experiments with ¹³C- or ²H-labeled precursors (e.g., ¹³C-glucose, ²H-deoxyxylulose) allow researchers to track carbon flux through the MVA and MEP pathways and quantify cross-talk between compartments [4] [6]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy can identify the position of incorporated labels in final terpenoid products, confirming their biosynthetic origin [4].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Terpenoid Pathway Analysis

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Inhibitors | Fosmidomycin (DXR inhibitor) [5], Mevinolin (Lovastatin, HMGR inhibitor) [8] | Pathway blockade studies | Inhibit specific enzymatic steps to probe pathway function and cross-talk |

| Isotopic Tracers | [1-¹³C]-Glucose, [U-¹³C]-Pyruvate, ²H-labeled DXP [4] [6] | Metabolic flux analysis | Track carbon flow through MVA/MEP pathways and quantify intermediate exchange |

| Analytical Standards | IPP, DMAPP, Mevalonic acid, MEP, HMBPP [1] [5] | Metabolite profiling (LC-MS/GC-MS) | Identify and quantify pathway intermediates and end products |

| Molecular Cloning Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems [8], ORBIT [1], Gateway-compatible vectors | Genetic manipulation | Create gene knockouts, knockdowns, and overexpression strains |

| Heterologous Hosts | Escherichia coli [9] [10], Saccharomyces cerevisiae [9] [10], Nicotiana benthamiana [8] | Pathway reconstitution & engineering | Express heterologous genes to characterize function and produce terpenoids |

| Enzyme Assay Kits | HMG-CoA reductase assay kit, IPP isomerase activity assay | In vitro enzyme kinetics | Measure catalytic activity and characterize enzyme properties |

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Terpenoid Pathway Analysis. Integrated approaches combining genetic manipulation, environmental/chemical treatments, and multi-faceted analysis are used to dissect the MVA and MEP pathways and their regulation.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Biotechnology

The MEP Pathway as a Antimicrobial Target

The MEP pathway is absent in humans but essential for the survival of many human bacterial pathogens and apicomplexan parasites, making it an attractive target for developing novel antimicrobials and herbicides [7] [5]. Enzymes such as DXR (target of fosmidomycin) and the Fe-S cluster enzymes IspG and IspH are particularly promising for drug development [5]. The unique metallochemistry and mechanisms of these enzymes offer opportunities for selective inhibition with minimal off-target effects in human hosts [7] [5].

Metabolic Engineering for Terpenoid Production

Metabolic engineering leverages the MVA and MEP pathways for sustainable terpenoid production in heterologous hosts, overcoming limitations of plant extraction and chemical synthesis [9] [10] [8].

Microbial Engineering: The MEP pathway in E. coli offers a higher theoretical carbon yield from glucose (30.2%) compared to the MVA pathway (25.2%) [7]. However, its complex regulation and oxygen sensitivity present challenges [7]. Consequently, many engineering efforts introduce the more tractable eukaryotic MVA pathway into E. coli or enhance the native MVA pathway in S. cerevisiae [9] [10]. Strategies include:

- Enhancing precursor supply by overexpressing rate-limiting enzymes (DXS, HMGR) [10] [8]

- Downregulating competing pathways [10]

- Engineering enzyme variants with improved activity and specificity [10]

- Utilizing fusion proteins to channel intermediates and prevent toxicity [10]

These approaches have successfully achieved high-titer production of valuable terpenoids, including β-farnesene (1.3 g/L in E. coli) and the antimalarial precursor artemisinic acid [9] [10].

Plant Metabolic Engineering: In native medicinal plants, metabolic engineering strategies focus on:

- Transcription factor overexpression to coordinately upregulate entire pathways [8]

- CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout of competing pathways to redirect flux [8]

- Multigene stacking to reconstruct complex pathways in heterologous plant hosts like Nicotiana benthamiana [8]

These interventions have led to substantial yield improvements, such as a 22.5-38.9% increase in artemisinin through HMGR overexpression and remarkable 25-fold enhancement of paclitaxel production via strategic co-expression approaches [8].

The two-pathway paradigm of terpenoid biosynthesis—compartmentalized synthesis via MVA and MEP—represents a fundamental evolutionary strategy for generating chemical diversity while maintaining regulatory flexibility. The distinct biochemistry, localization, and regulation of these pathways enable organisms to fine-tune terpenoid production in response to developmental needs and environmental challenges. From a biotechnology perspective, understanding and manipulating these pathways is critical for sustainable production of high-value terpenoids. The MEP pathway's role as an oxidative stress sensor further expands its significance beyond metabolism into cellular signaling [7]. Future research will continue to elucidate the complex regulatory networks and transport mechanisms governing these pathways, enabling more precise metabolic engineering strategies. As synthetic biology tools advance, the intelligent integration of MVA and MEP pathway modules in customized chassis systems will unlock new possibilities for terpenoid biomanufacturing, reinforcing the importance of this two-pathway paradigm in both basic research and industrial applications.

Terpene Synthases as Metabolic Gatekeepers in Scaffold Generation

Terpene synthases (TPSs) represent a pivotal enzyme family responsible for generating the foundational chemical scaffolds of over 80,000 terpenoid natural products. This review delineates the core mechanistic principles and evolutionary drivers that underpin the functional diversity of TPSs, framing their role within divergent strategies for expanding terpenoid chemodiversity. We examine how these metabolic gatekeepers transform a limited pool of linear prenyl diphosphate precursors into an immense array of cyclic and acyclic hydrocarbon skeletons, which serve as central intermediates for downstream modification. The discussion is situated within a broader thesis on terpene biosynthesis research, highlighting how lineage-specific expansion and functional diversification of TPS families enable plants to adapt to specialized ecological niches. This synthesis integrates current biochemical knowledge with emerging biotechnological applications, providing a foundational reference for researchers exploring terpenoid-based drug discovery and metabolic engineering.

Terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, constitute the largest and most chemically diverse class of natural products, with over 80,000 identified structures [11] [2]. These compounds are ubiquitous across all domains of life and perform essential functions in plant development, defense, chemical ecology, and adaptation [11] [4]. In plants, the vast majority of terpenoids function as specialized metabolites that mediate critical ecological interactions, including defense against herbivores and pathogens, attraction of pollinators, and facilitation of plant-to-plant communication [11] [4] [9]. The profound structural diversity of terpenoids directly underpins their wide-ranging bioactivities and economic applications, which span pharmaceuticals, fragrances, flavors, nutraceuticals, and biofuels [11] [4] [2].

The biosynthesis of terpenoid skeletons centers on the catalytic activity of terpene synthase (TPS) enzymes, which function as metabolic gatekeepers by converting a limited set of acyclic prenyl diphosphate substrates into a vast chemical library of hydrocarbon and, in some cases, oxygenated terpene scaffolds [11]. This scaffold-forming step represents the committed entry point into specialized terpenoid metabolism and serves as a fundamental control point for chemodiversity generation. Following TPS catalysis, the resulting scaffolds typically undergo extensive functionalization, primarily through cytochrome P450 monooxygenase-mediated oxygenation, followed by various secondary modifications that further enhance structural and functional diversity [11] [4].

This review explores the molecular mechanisms and evolutionary processes that enable TPS enzymes to generate remarkable terpenoid structural diversity, positioning TPS activity within a broader conceptual framework of divergent strategies in terpenoid biosynthesis research. We provide a comprehensive analysis of TPS biochemistry, structural biology, and genomic organization, supplemented with experimental methodologies and emerging biotechnological applications relevant to drug discovery and metabolic engineering.

Terpenoid Backbone Biosynthesis: Precursor Supply Pathways

The biosynthesis of all terpenoids originates from two universal 5-carbon building blocks, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) [4] [2]. These activated isoprene units are synthesized through two distinct, compartmentalized metabolic pathways in plants:

- The Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway: Primarily cytosolic, this pathway converts three molecules of acetyl-CoA into IPP through a series of six enzymatic steps [4] [9]. A key regulatory enzyme is HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR), which catalyzes the NADPH-dependent reduction of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, representing a major flux-control point [4]. The MVA pathway predominantly supplies precursors for sesquiterpenes (C15), triterpenes (C30), and polyterpenes [11].

- The Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathway: Located in the plastids, this pathway condenses pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) to form IPP and DMAPP via seven enzymatic steps [4] [2]. The first committed step is catalyzed by 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS), which significantly influences overall pathway flux [4]. The MEP pathway provides precursors for hemiterpenes (C5), monoterpenes (C10), diterpenes (C20), and tetraterpenes (carotenoids, C40) [11].

Although these pathways operate independently in different subcellular compartments, evidence indicates limited cross-talk between them, enabling some exchange of intermediates [4].

Table 1: Enzymes of the Prenyl Diphosphate Precursor Supply Pathways

| Pathway | Enzyme | EC Number | Reaction Catalyzed | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVA Pathway | Acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase (AACT) | 2.3.1.9 | Condenses two acetyl-CoA to acetoacetyl-CoA | First committed step; cytosolic |

| HMG-CoA synthase (HMGS) | 2.3.3.10 | Adds acetyl-CoA to acetoacetyl-CoA to form HMG-CoA | - | |

| HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR) | 1.1.1.34 | Reduces HMG-CoA to mevalonate (MVA) | Key regulatory step; consumes 2 NADPH; ER membrane-associated | |

| Mevalonate kinase (MVK) | 2.7.1.36 | Phosphorylates MVA to mevalonate-5-phosphate | ATP-dependent | |

| Phosphomevalonate kinase (PMK) | 2.7.4.2 | Phosphorylates to mevalonate-5-diphosphate | ATP-dependent | |

| Mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase (MVD) | 4.1.1.33 | Decarboxylates to form IPP | - | |

| MEP Pathway | DXS | 2.2.1.7 | Condenses pyruvate & GAP to DXP | Key regulatory step; plastid-localized |

| DXR | 1.1.1.267 | Rearranges & reduces DXP to MEP | NADPH-dependent | |

| ISPG/HDR | 1.17.7.1/1.17.7.4 | Converts HMBPP to IPP & DMAPP | Final step; produces both IPP & DMAPP | |

| Isomerization | IPP isomerase (IDI) | 5.3.3.2 | Interconverts IPP and DMAPP | Essential for balancing precursor pool |

Following their formation, IPP and DMAPP undergo chain elongation by isoprenyl diphosphate synthase (IDS) enzymes to produce the direct substrates for TPSs [4]. These head-to-tail condensations yield:

- Geranyl diphosphate (GPP, C10) - precursor to monoterpenoids

- Farnesyl diphosphate (FPP, C15) - precursor to sesquiterpenoids

- Geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP, C20) - precursor to diterpenoids

Terpene Synthases: Molecular Mechanisms of Scaffold Generation

Terpene synthases catalyze the most complex step in terpenoid formation, transforming linear, achiral prenyl diphosphates into a stunning array of stereo-chemically defined cyclic and acyclic hydrocarbons. A single TPS enzyme often produces multiple terpene products from a single substrate [11].

Universal Catalytic Mechanism

The TPS catalytic mechanism generally follows a conserved sequence of carbocation-driven steps [11]:

- Substrate Binding and Activation: The prenyl diphosphate substrate (GPP, FPP, or GGPP) binds within a metal-dependent active site, typically coordinated by Mg²⺠or Mn²⺠ions.

- Ionization-Initiation: The enzyme facilitates the ionization of the diphosphate group (PPi), generating a highly reactive allylic carbocation.

- Cyclization and Rearrangement: This initial carbocation undergoes a series of cyclizations, hydride shifts, and Wagner-Meerwein rearrangements, guided by the enzyme's active site contour and specific amino acid residues.

- Reaction Termination: The carbocation cascade is terminated, most commonly by deprotonation (yielding olefins) or nucleophile capture (often by water, yielding oxygenated terpenes).

The product outcome is exquisitely sensitive to the active site geometry, which positions the carbocation intermediates to dictate the specific cyclization and rearrangement pathways.

Table 2: Representative Terpene Synthase Products and Their Origins

| TPS Class | Primary Substrate | Representative Products | Biosynthetic Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpene Synthases | Geranyl Diphosphate (GPP) | Limonene, Pinene, Myrcene, Linalool | MEP Pathway; Plastids |

| Sesquiterpene Synthases | Farnesyl Diphosphate (FPP) | Bisabolene, Caryophyllene, Farnesene | MVA Pathway; Cytosol |

| Diterpene Synthases | Geranylgeranyl Diphosphate (GGPP) | Taxadiene, Copalyl Diphosphate, Sclareol | MEP Pathway; Plastids |

Structural Features and Domain Architecture

Most plant TPSs are characterized by a core α-helical structure, often described as a 'butterfly-fold' due to its topology [4]. The catalytic machinery relies on two key motifs for substrate binding and activation:

- DDxxD Motif: A conserved aspartate-rich region that coordinates the essential divalent metal ions (Mg²âº/Mn²âº) which, in turn, bind the substrate's diphosphate group.

- NSE/DTE Motif: (Asn-Ser-Glu/Asp-Thr-Glu) An equally conserved motif that further stabilizes the metal ion complex.

The plant TPS family is divided into seven phylogenetically distinct clades (TPS-a to TPS-h), which evolved from ancestral triterpene synthase- and prenyl transferase–type enzymes through repeated gene duplication events [11]. This lineage-specific expansion has resulted in TPS families ranging from a single gene to over 100 members in a given species, directly correlating with the terpenoid chemodiversity observed in nature [11].

Experimental Protocols for TPS Functional Characterization

Characterizing the function of a novel TPS enzyme involves a multi-step process to identify its substrates, products, and catalytic mechanism. Below is a generalized workflow and key methodological details.

Heterologous Expression and Protein Purification

Objective: To produce a functional, purified TPS protein for biochemical assays.

Detailed Protocol:

- Gene Isolation and Vector Construction: Amplify the TPS coding sequence (excluding predicted transit peptides for plastid-targeted enzymes) from cDNA. Clone the sequence into a suitable prokaryotic (e.g., pET, pGEX) or eukaryotic (e.g., pYES2, pPICZ) expression vector, incorporating an affinity tag (e.g., His₆-tag, GST-tag) for purification.

- Transformation and Expression:

- For E. coli (e.g., BL21-DE3): Transform the construct. Grow cultures in LB medium at 37°C to an OD₆₀₀ of 0.6-0.8. Induce protein expression with isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, typically 0.1-1.0 mM) and incubate at reduced temperature (16-22°C) for 16-20 hours to improve soluble protein yield.

- For S. cerevisiae: Transform using standard methods. Induce expression in selective medium with galactose.

- Cell Lysis and Purification: Pellet cells via centrifugation. Resuspend in lysis buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF) supplemented with lysozyme (for E. coli) and protease inhibitors. Lyse cells by sonication or French press. Clarify the lysate by high-speed centrifugation.

- Perform affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA (for His-tagged proteins) or Glutathione Sepharose (for GST-tagged proteins) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- Desalt the purified protein into an assay-compatible storage buffer (e.g., 25 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 10% glycerol) using size-exclusion chromatography. Determine protein concentration and aliquot for storage at -80°C.

In Vitro Enzyme Assay and Product Analysis

Objective: To determine the catalytic activity of the purified TPS using specific prenyl diphosphate substrates and to characterize the volatile terpene products.

Detailed Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: In a glass vial, assemble a reaction mixture containing:

- Assay Buffer: 25 mM HEPES or MOPS (pH 7.0-7.5)

- Divalent Cations: 10 mM MgClâ‚‚ and/or 1 mM MnClâ‚‚

- Substrate: 50-100 µM of GPP, FPP, or GGPP

- Enzyme: 10-100 µg of purified TPS

- Final volume: 500 µL - 1 mL

- Incubation and Extraction:

- Overlay the aqueous reaction mix with 300-500 µL of a pentane:diethyl ether (1:1) or pure hexane solvent to trap volatile products.

- Seal the vial and incubate at 30°C for 30-120 minutes with gentle agitation.

- After incubation, vortex thoroughly and centrifuge to separate phases. Carefully collect the organic (upper) layer containing the terpene products.

- Concentrate the extract under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas if necessary.

- Product Identification:

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): This is the primary tool for product identification. Inject 1-2 µL of the organic extract onto a non-polar or semi-polar GC column (e.g., DB-5ms). Use a temperature ramp program (e.g., 40°C for 2 min, then 10°C/min to 280°C).

- Data Analysis: Compare the mass spectra and retention times of the reaction products to those of authentic standards and mass spectral libraries (e.g., NIST, Adams Essential Oils). For novel compounds, NMR spectroscopy may be required for full structural elucidation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for TPS Research and Functional Analysis

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Key Features & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Prenyl Diphosphate Substrates (GPP, FPP, GGPP) | Natural substrates for in vitro TPS enzyme assays. | Commercially available but costly. Stability can be an issue; store at -80°C. |

| Affinity Purification Resins (Ni-NTA Agarose, Glutathione Sepharose) | Purification of recombinant His-tagged or GST-tagged TPS proteins. | Enables rapid, one-step purification. Imidazole (for His-tags) or glutathione (for GST-tags) used for elution. |

| Heterologous Host Systems (E. coli, S. cerevisiae) | Expression platforms for recombinant TPS production. | E. coli: Fast, high yield, but may lack post-translational modifications. S. cerevisiae: Eukaryotic folding machinery, suitable for larger/more complex TPSs. |

| GC-MS System with Non-Polar Column (e.g., DB-5) | Gold-standard for separation and identification of volatile terpene products. | Provides retention time and mass spectral data for comparison with libraries and standards. |

| Terpene Analytical Standards (e.g., Limonene, Pinene, Caryophyllene) | Reference compounds for definitive product identification via GC co-injection and MS comparison. | Critical for validating the identity of TPS products, especially in complex mixtures. |

| 1-Boc-azetidine-3-yl-methanol | 1-Boc-azetidine-3-yl-methanol, CAS:142253-56-3, MF:C9H17NO3, MW:187.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MDCC | MDCC, CAS:156571-46-9, MF:C20H21N3O5, MW:383.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Evolutionary Diversification and Emerging Biotechnological Applications

The profound functional plasticity of the TPS family is a direct result of evolutionary processes. Gene duplication is the primary driver, providing the genetic raw material for functional divergence [11]. Following duplication, TPS genes accumulate mutations that can lead to:

- Neofunctionalization: The evolution of novel catalytic functions, often through minor alterations in the active site that dramatically alter product specificity [11].

- Subfunctionalization: Partitioning of ancestral functions among duplicate genes.

- Loss of function: Pseudogenization.

This evolutionary trajectory has enabled plants to rapidly adapt their terpenoid blends to specific ecological pressures with minimal investment in evolving entirely new enzymes [11].

The strategic role of TPSs as metabolic gatekeepers makes them prime targets for metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. Advanced strategies now focus on:

- Heterologous Production: Reconstructing entire terpenoid pathways in microbial hosts like E. coli and S. cerevisiae for sustainable production [9] [10]. Success stories include the antimalarial drug artemisinin and the biofuels precursor β-farnesene [9] [10].

- Pathway Optimization: Enhancing precursor supply (MVA/MEP pathways), engineering TPSs for improved activity or altered product profile, and down-regulating competitive pathways [10].

- Precision Genome Editing: Using CRISPR/Cas systems to engineer TPS genes directly in plant genomes or to optimize microbial chassis [10].

Terpene synthases stand as quintessential metabolic gatekeepers, whose evolutionary history and catalytic prowess directly shape the vast chemical landscape of plant terpenoids. Their ability to generate a staggering array of scaffolds from a limited precursor pool exemplifies nature's efficiency in solving the problem of chemical diversity generation. The molecular and functional understanding of TPSs, as reviewed herein, provides a critical foundation for ongoing research within the divergent strategies framework of terpene biosynthesis. For drug development professionals and researchers, the continued elucidation of TPS mechanisms and evolution promises not only to unlock new bioactive terpenoid structures but also to provide the engineering blueprints for their sustainable and scalable production. Future research will undoubtedly delve deeper into the structure-function relationships of atypical TPSs, the regulatory networks controlling their expression, and their integration within modular metabolic pathways, further solidifying their central role in both natural chemical ecology and applied biotechnology.

The screening hypothesis posits that enzyme promiscuity—the ability of enzymes to catalyze reactions other than their primary function—serves as a fundamental engine for evolutionary innovation in chemical space. This review examines the mechanistic basis of catalytic promiscuity and its pivotal role in generating chemical diversity, with a specific focus on terpene biosynthesis as a model system. We present quantitative analyses of promiscuous enzyme families, detailed experimental methodologies for detecting and characterizing promiscuous activities, and computational frameworks for exploiting these properties in biocatalyst design. Within the context of divergent strategies in terpene biosynthesis research, we demonstrate how promiscuity-driven innovation provides organisms with adaptive advantages and offers researchers powerful tools for accessing novel chemical scaffolds with pharmaceutical relevance.

Enzyme promiscuity is defined as the capability of an enzyme to catalyze a reaction other than the reaction for which it has been specialized [12]. This phenomenon, alternatively termed "substrate ambiguity" or "catalytic cross-reactivity," provides the raw material for evolutionary innovation by enabling the emergence of novel metabolic functions without requiring de novo enzyme evolution [13]. The current evolutionary model holds that enzyme families expand through gene duplication events followed by acquisition of advantageous new functions, with the backbone folds and catalytic scaffolds being inherited alongside intrinsic catalytic capabilities [13].

The screening hypothesis formalizes this concept by proposing that natural selection screens the latent promiscuous activities of enzymes, favoring those secondary functions that provide selective advantages under changing environmental conditions or metabolic demands. This process enables rapid adaptation and metabolic expansion, particularly in specialized metabolism pathways such as those producing terpenoid compounds. In terpenoid biosynthesis, promiscuous enzymes serve as evolutionary starting points for generating the remarkable chemical diversity observed across plant lineages, with profound implications for drug discovery and metabolic engineering [14] [15].

Mechanistic Bases of Enzyme Promiscuity

Structural and Chemical Principles

The structural basis of enzyme promiscuity resides in three fundamental mechanistic categories that enable enzymes to accommodate alternative substrates and catalyze distinct reactions (Table 1).

Table 1: Mechanisms Underlying Enzyme Promiscuity

| Mechanism | Structural Basis | Representative Examples | Impact on Catalytic Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Site Plasticity | Conformational flexibility of active site residues and loops enables accommodation of diverse substrates | β-lactamase, sulfo-transferase, isopropylmalate isomerase [12] | Altered substrate specificity and reaction hydrolysis patterns |

| Substrate Ambiguity | Versatile active site architecture permits binding of structurally distinct substrates through multiple interaction modes | Cytochromes P450 (CYP3A4), salicylic acid binding protein [12] | Extreme promiscuity in substrate specificity and cooperative binding |

| Cofactor Ambiguity | Ability to utilize different metal cofactors or organic cofactors, altering reaction specificity | Farnesyl diphosphate synthase, NDM-1 metallo-β-lactamase [12] | Metal-dependent switching between metabolic pathways (e.g., FPP vs. GPP production) |

Active site plasticity enables conformational diversity that permits alternative substrate binding and catalysis. For instance, in serum paraoxonase, native lactonase and promiscuous phosphotriesterase activities are mediated by different residue sets within the same active site groove [12]. Similarly, enzymes in the haloalkanoate dehalogenase (HAD) superfamily possess architectures that support both specificity and ambiguity, with structural features that enable functional divergence among phylogenetically related members [13].

Quantitative Assessment of Promiscuity

Substrate specificity profiling using structurally diverse chemical libraries enables quantitative assessment of enzyme promiscuity. Genome-wide studies of Escherichia coli HAD superfamily members demonstrate that these phosphatases can hydrolyze a wide range of phosphorylated compounds, including sugars, nucleotides, organic acids, coenzymes, and small phosphodonors [13]. The substrate ranges, while broad, typically show preference for metabolites downstream in their respective pathways, preventing depletion of upstream intermediates—an elegant evolutionary compromise between versatility and metabolic efficiency.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Promiscuous Enzyme Families

| Enzyme Family | Representative Member | Substrate Range | Catalytic Efficiency Range (kcat/Km, Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹) | Biological Functions Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAD Superfamily | cN-IIIB (human) | CMP, UMP, GMP, AMP, m7GMP [13] | 6.5×10ⴠ- 8.7×10ⴠ| Nucleotide metabolism, antimetabolite removal |

| Thioesterases (Hotdog Fold) | EntH (E. coli) | Aromatic hydroxylated benzoyl-CoAs, hydroxylated phenylacetyl-CoA [13] | >1×10ⴠ- 1.5×10ⵠ| Proofreading in enterobactin biosynthesis |

| Cytochrome P450 | CYP3A4 (human) | Extreme substrate diversity | Variable | Drug metabolism, natural product diversification |

| Terpene Synthases | Tomato TPS family | 34 distinct activities [15] | Variable | Diversification of specialized metabolism |

The impact of substrate ambiguity at the cellular level is substantial, with genome-scale metabolic network modeling suggesting that approximately 37% of metabolic enzymes in E. coli exhibit some degree of promiscuity, collectively catalyzing at least 65% of metabolic reactions [13].

Terpene Biosynthesis: A Paradigm for Promiscuity-Driven Innovation

Architectural Foundations of Terpene Diversity

Terpene biosynthesis represents a premier model system for studying promiscuity-driven chemical innovation. The terpene synthase (TPS) family exemplifies how enzyme promiscuity generates structural diversity from a limited set of precursor molecules. In tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), the complete functional characterization of 34 TPS genes revealed one isoprene synthase, 10 monoterpene synthases, 17 sesquiterpene synthases, and six diterpene synthases, with varying specificity for trans- and cis-prenyl diphosphate substrates [15]. This functional diversity arises from a combination of active site plasticity and substrate ambiguity, enabling a single enzyme scaffold to generate multiple products.

The functional characterization of the tomato TPS family provides unprecedented insight into the quantitative landscape of terpene structural diversity. Among the 34 functional TPS enzymes identified, subcellular localization varies considerably, with six monoterpene synthases being plastidic, four cytosolic, sesquiterpene synthases predominantly cytosolic (with one mitochondrial exception), and diterpene synthases distributed between plastids, cytosol, and mitochondria [15]. This compartmentalization, coupled with promiscuous prenyl diphosphate utilization, enables the generation of remarkable chemical diversity from conserved precursor pools.

Cytochrome P450s: Multifunctional Oxidations in Terpene Diversification

Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs) further expand terpene structural diversity through promiscuous oxidation reactions. Recent research in Aconitum species has identified 14 divergent P450s involved in diterpenoid biosynthesis, with eight demonstrating multifunctional capabilities by catalyzing oxidation at seven different positions on ent-atiserene and ent-kaurene scaffolds [16]. This remarkable plasticity in selective diterpene oxidation enables the combinatorial biosynthesis of bioactive compounds such as tripterifordin and guan-fu diterpenoid A, along with 14 novel atiserenoids, some exhibiting allelopathic activity [16].

The functional promiscuity of these P450s exemplifies the screening hypothesis in action, whereby ancestral enzymes with broad substrate specificities undergo gene duplication and functional divergence to generate new metabolic capabilities. Protein analysis and mutagenesis experiments have identified key residues that tune P450 activity and product profiles, revealing the structural basis for their functional divergence [16].

Experimental Approaches for Characterizing Promiscuous Activities

In Vitro Specificity Profiling

Comprehensive characterization of enzyme promiscuity requires systematic screening against diverse substrate libraries. For phosphatases of the HAD superfamily, specificity profiling against 80 representative phosphorylated metabolites has proven effective in mapping functional space [13]. Similarly, for thioesterases, screening against a broad range of acyl-CoA substrates enables determination of substrate preferences and identification of potential proofreading functions [13].

Protocol: High-Throughput Enzyme Specificity Screening

Library Design: Assemble a structurally diverse compound library representing potential physiological and non-physiological substrates. For terpene synthases, include both trans- and cis-prenyl diphosphates of varying chain lengths (C10-C25) [15].

Enzyme Production: Clone and express target enzymes in suitable heterologous systems (e.g., E. coli). For membrane-associated enzymes like P450s, employ co-expression with appropriate redox partners.

Activity Assays: Conduct kinetic assays under standardized conditions (pH, temperature, cofactors). For terpene synthases, employ GC-MS analysis of volatile products; for P450s, utilize LC-MS for oxidized products.

Data Analysis: Calculate kinetic parameters (kcat, Km, kcat/Km) and generate substrate specificity profiles. Identify catalytic efficiency thresholds (typically kcat/Km ~10³-10â´ Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹ for promiscuous activities) [13].

Functional Validation: For identified activities, validate physiological relevance through genetic approaches (knockout/complementation) and metabolic profiling.

In Vivo Functional Screening

In vivo screening provides complementary information about promiscuous activities under physiological conditions. For example, screening 62 putative thioesterases through fatty acid titer analysis in E. coli revealed substrate ambiguity with preferential activity toward downstream acyl-CoAs in metabolic pathways [13]. This approach captures the influence of cellular context, including substrate availability, compartmentalization, and potential regulatory interactions.

Protocol: In Vivo Functional Screening in Microbial Systems

Strain Engineering: Construct microbial hosts (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae) with engineered precursor supply and simplified metabolic backgrounds to enhance detection sensitivity.

Pathway Reconstitution: Express candidate enzymes in appropriate combinatorial assemblies. For diterpene biosynthesis, co-express upstream pathway enzymes (DXS, GGPPS) with TPS and P450 candidates [16].

Metabolite Profiling: Employ untargeted metabolomics to detect novel products resulting from promiscuous activities. Use stable isotope labeling to trace metabolic flux through alternative pathways.

Product Identification: Combine chromatographic separation with high-resolution mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy for structural elucidation of novel compounds.

Functional Correlation: Correlate enzyme expression levels with product profiles across different genetic backgrounds and growth conditions.

Research Reagent Solutions for Terpene Biosynthesis Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Enzyme Promiscuity in Terpene Biosynthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prenyl Diphosphate Substrates | GPP, NPP, FPP, GGPP | Substrates for terpene synthase activity assays | Use both trans and cis isomers; assess stability in assay conditions [15] |

| Heterologous Expression Systems | E. coli, Nicotiana benthamiana, S. cerevisiae | Recombinant enzyme production for in vitro studies | Co-express redox partners for P450s; optimize codon usage [16] |

| Pathway Engineering Tools | pEAQ-HT vectors, MEP pathway enzymes (DXS, GGPPS) | Boost precursor supply for in vivo screening | Modular vector systems enable combinatorial assembly [16] |

| Analytical Standards | Authentic terpene standards, stable isotope-labeled precursors | Metabolite identification and quantification | Include both free and glycosidically-bound forms for complete profiling [17] |

| Chemical Libraries | Phosphorylated metabolites, acyl-CoA derivatives, diversified terpene scaffolds | Specificity profiling and promiscuity mapping | Structural diversity more important than library size [13] |

| Cofactor Systems | NADPH regeneration systems, metal cofactors (Mg²âº, Mn²âº) | Support for oxidative and metal-dependent enzymes | Test multiple divalent cations for cofactor ambiguity studies [12] |

The screening hypothesis provides a powerful framework for understanding how enzyme promiscuity drives chemical innovation in natural systems and offers strategic guidance for engineering novel biocatalytic functions. In terpene biosynthesis, the functional characterization of complete enzyme families—from the 34 TPS genes in tomato to the multifunctional P450s in Aconitum—reveals how promiscuity enables rapid diversification of chemical structures from conserved genetic and metabolic platforms [15] [16].

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the structural determinants of promiscuity through combined computational and experimental approaches, developing predictive models for enzyme evolvability, and engineering promiscuous enzyme families for applications in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. The integration of functional genomics, structural biology, and computational modeling will further illuminate how nature screens promiscuous activities to generate chemical novelty, providing both fundamental insights into evolutionary mechanisms and practical tools for accessing bioactive compounds with pharmaceutical potential.

Terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, represent the largest and most structurally diverse class of natural products with over 80,000 identified compounds, playing crucial roles in both primary and secondary metabolism across living organisms [2]. These compounds are constructed from repeating five-carbon isoprene units (C5H8) and are classified based on the number of these units in their core structure: hemiterpenoids (C5), monoterpenoids (C10), sesquiterpenoids (C15), diterpenoids (C20), sesterterpenoids (C25), triterpenoids (C30), and tetraterpenoids (C40) [10] [18] [2]. The fundamental carbon skeletons of terpenoids range from simple acyclic chains to complex polycyclic systems with multiple rings and stereocenters, with this structural diversity arising from complex biosynthetic mechanisms that modify and cyclize the basic isoprenoid precursors [19].

This structural classification is particularly relevant within the context of divergent strategies in terpene biosynthesis research, where minimal modifications to biosynthetic pathways or enzyme engineering can lead to significant diversification of terpene skeletons. Understanding the spectrum from acyclic to polycyclic terpene structures provides the foundation for developing these strategies to access novel compounds with potential applications in pharmaceuticals, fragrances, flavors, and biofuels [20] [21]. The structural complexity in terpenes, leading to the formation of such diverse structures, is justified by an understanding of terpenoid biosynthesis, particularly the enzymatic cyclization reactions that transform acyclic precursors into complex cyclic and polycyclic systems [2].

Fundamental Terpenoid Classification Systems

Carbon Skeleton Classification

The classification of terpenoids begins with the number of isoprene units, which determines the basic carbon framework and properties of the compound. The table below summarizes the major terpenoid classes based on carbon count:

Table 1: Terpenoid Classification by Carbon Skeleton

| Terpenoid Class | Carbon Atoms | Isoprene Units | Representative Examples | Biological Functions & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemiterpenoids | 5 | 1 | Isoprene, Isoamyl alcohol | Basic building blocks; emitted by plants [18] |

| Monoterpenoids | 10 | 2 | Limonene, Geraniol, Linalool | Floral and citrus aromas; antimicrobial properties [10] [22] |

| Sesquiterpenoids | 15 | 3 | Farnesene, Patchoulol, Caryophyllene | Plant defense compounds; anticancer and neuroprotective activities [10] [23] |

| Diterpenoids | 20 | 4 | Taxol, Gibberellin, Crinipellins | Plant hormones (gibberellins); pharmaceuticals (anticancer Taxol) [24] [20] |

| Sesterterpenoids | 25 | 5 | Geranylfarnesol | Rare class; various biological activities [25] |

| Triterpenoids | 30 | 6 | Squalene, Cycloartenol | Membrane components; precursors to steroids [25] [22] |

| Tetraterpenoids | 40 | 8 | Carotenoids (β-carotene) | Photosynthetic pigments; antioxidants [2] |

Structural Complexity: From Acyclic to Polycyclic

Beyond carbon count, terpenoids are classified based on their structural complexity, particularly the presence and arrangement of ring systems:

Acyclic Terpenoids: These possess open-chain structures without ring systems. Examples include geraniol (monoterpene), farnesol (sesquiterpene), and geranylgeraniol (diterpene). Their flexibility allows for various conformations but generally less structural complexity than their cyclic counterparts [2].

Monocyclic Terpenoids: Contain a single ring system. Limonene, a common monoterpene found in citrus fruits, features a single six-membered ring and exemplifies this class [10] [23].

Bicyclic Terpenoids: Feature two fused ring systems. α-Pinene (monoterpene) and caryophyllene (sesquiterpene) are prominent examples, often contributing to the characteristic scents of pine and cannabis, respectively [22].

Polycyclic Terpenoids: Contain three or more fused ring systems, representing the pinnacle of structural complexity in terpenoid biosynthesis. Examples include the tetracyclic diterpene taxol, the pentacyclic triterpene cycloartenol, and the tetraquinane diterpenes like crinipellins and tetraisoquinene, which possess a dense 5/5/5/5-fused tetracyclic skeleton [24] [20] [22].

This progression from acyclic to polycyclic structures is governed by specialized enzymes called terpene synthases or cyclases, which catalyze the cyclization and rearrangement reactions that create this remarkable diversity [25].

Biosynthetic Mechanisms Generating Skeletal Diversity

The transformation of acyclic prenyl diphosphate precursors into diverse terpenoid skeletons is catalyzed by terpene cyclases (TCs), also known as terpene synthases (TPSs). These enzymes chaperone carbocation-driven cyclization cascades, with the class of TC determining the initial activation mechanism [25].

Diagram 1: Terpene Cyclization Mechanism

Class I and Class II Terpene Cyclases

Terpene cyclases are divided into two primary classes based on their reaction mechanisms:

Class I TCs initiate cyclization by abstracting the diphosphate group from the acyclic prenyl diphosphate substrate (GPP, FPP, or GGPP) using a trinuclear divalent metal ion cluster, typically Mg²âº. This abstraction generates an initial carbocation that triggers the cyclization cascade. Class I TCs are characterized by conserved metal-binding motifs, primarily the DDxxD and NSE/DTE motifs [25].

Class II TCs instead initiate cyclization by protonating a terminal double bond or epoxide of the substrate, leaving any diphosphate group intact. This protonation is typically mediated by a central acidic aspartate residue, often found within a DxDD motif. Class II TCs often act as the first step in the biosynthesis of complex terpenoids, including the gibberellin family of phytohormones and various fungal meroterpenoids [25].

Following the initial cation formation, both classes of enzymes guide the substrate through a series of cyclization and rearrangement steps, stabilized by aromatic residues within the active site, before the final carbocation is quenched by deprotonation or water attack [25].

Structural Features of Terpene Cyclases

The three-dimensional architecture of terpene cyclases is crucial for their function. Most canonical TCs feature all α-helical folds and are composed of α, β, and γ domains in various combinations. The catalytic domain of class I TCs is primarily the α-domain, which houses the metal-binding motifs. In contrast, class II TCs typically position the substrate in the cleft between the β and γ domains, with the functional β domain containing the catalytic DxDD motif. Some TCs contain all three domains and can be monofunctional or bifunctional, possessing both class I and class II activities [25]. The active site cavity size and shape are key determinants of the product profile, with enzymes producing larger terpenes generally possessing more expansive cavities [25].

Experimental Approaches for Terpenoid Research

Genome Mining and Heterologous Expression

Modern discovery of novel terpene skeletons relies heavily on genome mining to identify putative terpene synthase genes from diverse organisms. This approach has revealed a vast, untapped reservoir of bacterial TSs, with over 5,000 putative proteins identified in the UniProt database belonging to just one terpene cyclase subfamily [20]. A 2025 study screened 334 uncharacterized bacterial TSs from 8 phyla and found 125 (37%) were active as diterpene synthases, leading to the discovery of three previously unreported diterpene skeletons [20].

Heterologous expression in model systems like E. coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae is then used to characterize the function of these putative TSs. An engineered E. coli strain that overproduces geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) is particularly valuable for studying diterpene synthases [20]. For plant TPSs, transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana is a powerful alternative, often co-infiltrated with genes for rate-limiting enzymes in precursor pathways (e.g., HMGR, DXS) to boost metabolic flux toward the terpenoid of interest [22].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Terpenoid Biosynthesis Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Prenyl Diphosphates (GPP, FPP, GGPP) | Substrates for in vitro terpene synthase assays | Enzyme characterization and kinetic studies [22] |

| Codon-Optimized Synthetic Genes | Heterologous expression of terpene synthases in microbial hosts | Functional characterization of putative TSs from diverse sources [20] |

| HMGR/DXS Expression Constructs | Enhance flux through MVA or MEP pathways in host systems | Boost precursor supply for terpene production in N. benthamiana or yeast [22] |

| Squalene, Oxidosqualene | Substrates for triterpene cyclases (TTCs) | Study of triterpene biosynthesis (e.g., cycloartenol formation) [22] |

| Authentic Terpenoid Standards | Reference compounds for GC-MS and LC-MS analysis | Identification and quantification of terpene products [22] |

Analytical and Structural Elucidation Techniques

The complex structures of terpenoids, particularly novel polycyclic skeletons, require sophisticated analytical techniques for elucidation.

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): This is the workhorse for analyzing volatile terpenes (e.g., mono- and sesquiterpenes). It separates compounds and provides mass spectral data for initial identification [23] [22].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Essential for determining the planar structure and relative configuration of terpenoids. 1D (¹H, ¹³C) and 2D (COSY, HSQC, HMBC, NOESY) NMR experiments provide detailed information about carbon connectivity and spatial relationships between atoms [20].

- Vibrational Circular Dichroism (VCD): A powerful technique for determining the absolute configuration of chiral terpenes in solution without the need for crystallization or chemical derivatization. This method was crucial for establishing the absolute stereochemistry of novel diterpenes like tetraisoquinene and salbirenol [20].

Diagram 2: Terpenoid Discovery Workflow

Case Studies in Skeletal Diversity

Discovery of Novel Bacterial Diterpene Skeletons

Recent genome mining efforts have dramatically expanded the known chemical space of bacterial diterpenes. A landmark 2025 study characterized 31 bacterial diterpene synthases, leading to the isolation and structural elucidation of 28 diterpenes. These compounds showcased the remarkable diversity of bacterial terpenoid metabolism, falling into several categories [20]:

- Previously Unreported Skeletons: The study identified three completely new diterpene skeletons: Tetraisoquinene (1) from Melittangium boletus, featuring a 5/5/5/5-fused angular tetraquinane system; Salbirenol (2) from Streptomyces albireticuli, with a 7/5/6-tricyclic skeleton; and Chitino-2,5(6),9(10)-triene (3) from Chitinophaga japonensis, possessing a novel 5/11-bicyclic skeleton [20].

- Skeletons Known in Other Organisms: Several diterpenes were identified that were known from plants or fungi but had not been previously reported from bacteria, highlighting the convergent evolution of terpenoid biosynthesis across kingdoms.

- New Isomers of Known Skeletons: The research also uncovered new structural and stereochemical isomers of previously known diterpene skeletons, demonstrating how minor sequence variations in TSs can lead to significant structural diversification [20].

Tissue-Specific Terpene Synthase Expression in Plants

Transcriptomic analysis of Convallaria keiskei (Lily of the Valley) revealed how structural diversity is generated within a single organism. This study identified fifteen putative terpene synthase (TPS) genes with distinct tissue-specific expression patterns [18]:

- Flower TPSs: Were associated with the synthesis of a diverse array of compounds including geraniol, germacrene, linalool, nerolidol, trans-ocimene, and valencene, contributing to the characteristic floral scent.

- Leaf TPSs: Were primarily linked to the biosynthesis of kaurene (a diterpene precursor to gibberellins) and trans-ocimene.

- Root TPSs: Expressed genes for synthesizing kaurene, trans-ocimene, and valencene.

This tissue-specific specialization demonstrates how plants differentially employ terpene skeletal diversity for specific ecological functions, such as pollinator attraction in flowers and defense in roots and leaves [18].

The structural classification of terpenoids from acyclic to polycyclic skeletons provides a fundamental framework for understanding their biosynthesis, function, and potential applications. The recent expansion of known terpene skeletons, particularly from under-explored sources like bacteria and non-model plants, underscores the vast untapped chemical space that remains to be discovered [20] [22].

Within the context of divergent biosynthesis strategies, this structural knowledge is paramount. Understanding the precise mechanisms by which terpene cyclases generate skeletal diversity—how single amino acid changes can alter product profiles, or how nature repurposes basic catalytic folds to create new skeletons—provides the blueprint for engineering efforts [25]. The future of terpenoid research lies in leveraging this understanding to develop robust platforms for the sustainable production of existing high-value terpenoids and the deliberate creation of novel ones through synthetic biology [10] [21]. This will involve advanced protein engineering of terpene synthases, combinatorial biosynthesis, and optimization of microbial and plant-based production systems to fully realize the potential of terpenoid structural diversity for drug development, green chemistry, and renewable energy [2] [21].

Harnessing Biosynthetic Logic for Engineering and Drug Discovery

Metabolic engineering utilizes microbial hosts as programmable cell factories for the sustainable production of high-value terpenoids, a class of natural products with extensive applications in pharmaceuticals, fragrances, and fuels [10] [26]. This field has evolved from imitating natural biosynthetic pathways toward engineering an expanded "terpenome" with desirable properties not found in nature [26]. The structural diversity of over 80,000 identified terpenoids stems from a conserved biosynthetic logic that is uniquely amenable to engineering approaches [27] [26].

Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have emerged as predominant chassis organisms, each offering distinct advantages for terpenoid biosynthesis [10]. Their selection represents a fundamental strategic divergence in terpene biosynthesis research, balancing the rapid growth and well-characterized genetics of prokaryotic systems against the eukaryotic compartmentalization and post-translational modification capabilities of yeast [28] [29]. This technical guide examines the core principles, experimental methodologies, and emerging frontiers in metabolic engineering of these microbial hosts within the broader context of terpenoid research.

Fundamental Pathways and Strategic Host Selection

Native Terpenoid Biosynthetic Pathways from an Engineering Perspective

All terpenoid biosynthesis originates from two universal C5 precursors, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), produced through one of two evolutionarily distinct metabolic routes [26].

The Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway: Native to yeast and the cytosol of plants, this pathway begins with acetyl-CoA and proceeds through six enzymatic steps to produce IPP [26] [9]. From an engineering perspective, a significant bottleneck occurs at 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR), which is tightly regulated and consumes two NADPH molecules per IPP produced [26] [29]. Engineering strategies often employ truncated, deregulated HMGR variants to overcome this limitation [26].

The Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathway: Predominant in E. coli and plant plastids, this pathway initiates with pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) [26] [9]. The MEP pathway offers higher theoretical carbon yield and lower ATP consumption compared to the MVA pathway [26]. The first committed step catalyzed by 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS) represents a primary engineering constraint due to its low catalytic efficiency [26].

Following precursor synthesis, prenyltransferases catalyze the condensation of IPP and DMAPP to generate linear isoprenoid precursors of various chain lengths (C10, C15, C20), serving as critical regulatory nodes for directing metabolic flux toward specific terpenoid classes [10] [26].

Comparative Host Analysis

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of E. coli and S. cerevisiae as Terpenoid Cell Factories

| Aspect | E. coli (Prokaryotic) | S. cerevisiae (Eukaryotic) |

|---|---|---|

| Native Pathway | MEP pathway | MVA pathway |

| Genetic Manipulation | Easy, rapid cycling, extensive toolkit | Sophisticated tools, but more complex |

| Growth Rate | Very fast, high cell densities | Moderate |

| Post-Translational Modifications | Limited, unsuitable for complex eukaryotic enzymes | Endorsed, capable of functional P450 expression |

| Precursor Supply | Enhanced via MVA pathway introduction | Enhanced via MVA pathway optimization |

| Compartmentalization | Absent | Present (organelles enable pathway segregation) |

| Toxicity Tolerance | Variable, requires management | Generally robust, tolerates diverse compounds |

| Ideal Terpenoid Targets | Volatile mono/sesquiterpenes, non-natural derivatives | Complex oxygenated terpenes, triterpene scaffolds |

| Maximum Achieved Titers | β-Farnesene: 1.3 g/L [9]; Amorpha-4,11-diene: 8.32 g/L [26] | Artemisinic acid: 25 g/L [26] [29]; Bisabolene: 18.6 g/L [26] |

Core Metabolic Engineering Strategies

Precursor Supply and Flux Enhancement

A foundational strategy in both hosts involves enhancing the supply of universal terpenoid precursors IPP and DMAPP. In S. cerevisiae, this typically involves overexpression of rate-limiting enzymes in the native MVA pathway, particularly tHMGR (truncated HMG-CoA reductase), to alleviate natural feedback inhibition [26] [29]. Additional approaches include balancing the expression of upstream enzymes such as ERG10, ERG13, and ERG12 to create a coordinated flux push toward IPP/DMAPP [10].

For E. coli, which natively employs the MEP pathway, two strategic approaches have emerged: optimization of the endogenous pathway through DXS overexpression and modulation of other MEP enzymes, or introduction of the complete heterologous MVA pathway to bypass native regulation [26]. The latter approach has demonstrated superior flux capabilities when properly optimized [26].

Table 2: Representative Terpenoid Production Achievements in Engineered Microbial Hosts

| Product | Host | Pathway | Key Engineering Strategy | Maximum Titer | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Farnesene | E. coli | MEP | Enhanced precursor supply (IPP/DMAPP) | 1.3 g/L | [9] |

| Amorpha-4,11-diene | E. coli | MEP | Semi-continuous biomanufacturing | 8.32 g/L | [26] |

| Artemisinic acid | S. cerevisiae | MVA | Plant dehydrogenase introduction; additional cytochrome P450 | 25 g/L | [26] [29] |

| Bisabolene | S. cerevisiae | MVA | MVA pathway enhancement; temperature-sensitive regulation | 18.6 g/L | [26] |

| β-Farnesene | Y. lipolytica | MVA | Acetyl-CoA boosting; large-scale optimization | 35.2 g/L | [26] |

| Sclareol | Y. lipolytica | MVA | Enzyme engineering; increasing GGPPS supply | 12.9 g/L | [26] |

| Protopanaxadiol | S. cerevisiae | MVA | Full pathway reconstruction with P450s | 11 g/L | [29] |

| Taxadiene | E. coli | MEP | MVA pathway introduction; metabolic balancing | >1 g/L | [29] |

Pathway Regulation and Competing Flux Manipulation

Competing metabolic pathways represent significant drains on terpenoid precursor availability. In S. cerevisiae, ERG9 (squalene synthase) diverts farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) toward sterol biosynthesis, substantially reducing sesquiterpene yields when unregulated [26]. Successful engineering approaches have employed promoter replacement to downregulate ERG9 expression or CRISPR-based editing to dynamically control this metabolic competitor [26].

In E. coli, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) has emerged as a powerful tool for repressing competing pathways and redirecting flux toward target products [30]. This approach enables fine-tuning of central carbon metabolism without complete gene knockout, maintaining host viability while enhancing precursor availability for heterologous pathways.

Enzyme Engineering and Heterologous Expression

The functional expression of plant-derived terpene synthases and cytochrome P450 enzymes presents distinct challenges in microbial hosts. In E. coli, solubility and proper folding of eukaryotic enzymes often require codon optimization, fusion tags, and co-expression with chaperones [27]. S. cerevisiae inherently provides a more favorable environment for eukaryotic enzyme functionality, particularly for membrane-associated P450s that require endoplasmic reticulum docking [28] [9].

Advanced enzyme engineering approaches include:

- Directed Evolution: Creating mutant libraries and screening for improved activity, stability, or substrate specificity [10]

- Rational Design: Using structural information to make targeted mutations that enhance catalytic efficiency [10]

- Fusion Protein Strategies: Linking terpene synthases with prenyltransferases to promote substrate channeling and reduce byproduct formation [26]

Figure 1: Integrated Metabolic Engineering Workflow for Terpenoid Production in Microbial Hosts

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Standard Protocol for Terpenoid Pathway Assembly

Materials and Strains:

- E. coli DH5α: Cloning strain for plasmid construction [30]

- E. coli BW25113: Production host with clean genetic background [30]

- S. cerevisiae CEN.PK2: Preferred laboratory strain with well-characterized metabolism

- Vectors: pYB1a, pSB1c (expression vectors), dCas9 (CRISPRi system) [30]

Gibson Assembly for Pathway Construction:

- Design primers with 20-40 bp overlaps for adjacent DNA fragments

- Amplify gene fragments and vector backbone via PCR

- Treat vector backbone with DpnI to remove methylated template DNA

- Combine DNA fragments with Gibson Assembly Master Mix (NEB)

- Incubate at 50°C for 15-60 minutes

- Transform into competent E. coli DH5α via heat shock (42°C, 30 seconds) [30]

- Plate on selective media and verify colonies by colony PCR and sequencing

Induction and Cultivation:

- Inoculate single colonies into 5 mL LB (E. coli) or YPD (yeast) with appropriate antibiotics

- Grow overnight at 37°C (E. coli) or 30°C (yeast) with shaking at 220 rpm

- Transfer 1 mL overnight culture to 100 mL ZYM-5052 autoinduction medium (E. coli) or appropriate induction medium for yeast [30]

- For CRISPRi strains, add IPTG to final concentration of 1 mM to induce dCas9 expression [30]

- Cultivate at 30°C with shaking at 220 rpm for 12-48 hours, monitoring growth by OD600

Analytical Methods for Terpenoid Quantification

Sample Preparation:

- Harvest cells by centrifugation (4,200 rpm, 10 minutes)

- For intracellular terpenoids, resuspend cell pellet in phosphate buffer and disrupt by sonication

- Extract terpenoids with organic solvents (ethyl acetate or hexane)

- Concentrate extracts under nitrogen gas for GC-MS analysis

GC-MS Analysis:

- Instrument: Agilent 7890B GC coupled to 5977A MSD

- Column: HP-5MS UI (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm)

- Temperature program: 60°C (hold 2 min), ramp to 300°C at 10°C/min, hold 5 min

- Injection volume: 1 μL in split mode (split ratio 10:1)

- Quantification using calibration curves of authentic standards

Advanced Engineering Toolkits

Genome Editing Technologies

CRISPR-Cas Systems:

- CRISPR-Cas9: Enables precise gene knockouts, particularly effective for eliminating competing pathways in both E. coli and yeast [29]

- CRISPRi: Allows tunable repression of target genes without DNA cleavage, ideal for balancing essential metabolic pathways [30]

- Base Editing: Achiezes point mutations without double-strand breaks, useful for enzyme engineering and creating regulatory mutants [10]

Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE):

- Particularly effective in E. coli for simultaneous modification of multiple genomic loci

- Enables rapid optimization of enzyme expression levels and regulatory elements

- Can be combined with CRISPR systems for enhanced efficiency

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Engineering of Terpenoid Pathways

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Host Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pYB1a, pSB1c, dCas9 | Heterologous gene expression and regulation | E. coli [30] |

| Pathway Enzymes | HMAS homologs, Terpene synthases, P450s | Catalyze specific steps in terpenoid biosynthesis | Both [10] [30] |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, CRISPRi, Base editors | Targeted genetic modifications | Both [10] [29] |

| Promoter Systems | Constitutive (PGPD, PTEF); Inducible (PAOX1, PTET) | Transcriptional control of pathway genes | Both (yeast-specific examples) [28] |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance (AmpR, KanR); Auxotrophic markers (URA3, LEU2) | Selective pressure for plasmid/maintenance | Both |

| Fermentation Media | ZYM-5052 autoinduction medium; Defined mineral media | Support high-cell-density cultivation | Both [30] |

| Analytical Standards | Limonene, geraniol, farnesene, artemisinic acid | Quantification and method validation | Both [10] |

| ImmTher | ImmTher, CAS:130114-83-9, MF:C65H116N6O21, MW:1317.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Methyl 3-hydroxydodecanoate | Methyl 3-hydroxydodecanoate, CAS:72864-23-4, MF:C13H26O3, MW:230.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Figure 2: Terpenoid Biosynthetic Pathways and Key Engineering Nodes in Microbial Hosts

Emerging Frontiers and Industrial Translation

Non-Natural Terpenoid Biosynthesis

A transformative frontier involves expanding beyond nature's biosynthetic capabilities through the integration of artificial metalloenzymes and abiotic catalysis into engineered living systems [26]. Engineered cytochrome P450 variants capable of catalyzing non-natural carbene transfer reactions (e.g., cyclopropanation) enable the functionalization of terpene scaffolds with chemical groups not found in natural products [26]. This hybrid biosynthetic-chemical approach dramatically expands the accessible chemical space of terpenoids, potentially yielding compounds with improved bioactivity, metabolic stability, or novel functions [26].

Scale-Up and Bioprocess Engineering

Successful laboratory-scale terpenoid production must be translated to industrially viable processes through optimized fermentation strategies:

High-Cell-Density Cultivation (HCDC):

- Employed in scalable bioreactor systems (5L to industrial scale)

- Enables precise control of dissolved oxygen, pH, and nutrient feeding

- Achieved MA titer of 9.58 g/L in engineered E. coli [30]

Two-Phase Extraction Systems:

- Addition of organic overlay (e.g., dodecane) for in situ product removal

- Mitigates terpenoid toxicity and potential feedback inhibition

- Enables continuous fermentation processes

The strategic selection and engineering of microbial hosts represents a cornerstone of modern terpenoid biosynthesis research. The divergent approaches of utilizing E. coli versus S. cerevisiae reflect complementary philosophies in metabolic engineering: the optimization of prokaryotic efficiency versus the harnessing of eukaryotic complexity. As synthetic biology tools advance, the distinction between these platforms continues to blur, with researchers increasingly creating hybrid solutions that incorporate the strengths of both systems.

The integration of systems biology, computational design, and synthetic chemistry is pushing the field toward programmable biosynthesis of both natural and non-natural terpenoids. This evolution from imitation of nature to its strategic enhancement underscores the transformative potential of microbial cell factories in creating a sustainable, scalable supply of valuable terpenoid compounds for pharmaceutical, fragrance, and industrial applications. Future progress will likely depend on intelligent integration of multi-omics data, machine learning-guided design, and innovative bioprocessing strategies that collectively address the persistent challenges of metabolic balance, cytotoxicity, and economic viability at industrial scales.

Protein Engineering of Terpene Synthases and Cytochrome P450s