Computational Tools for Biosynthetic Pathway Prediction: A Guide for Drug Development and Synthetic Biology

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the computational tools and methodologies revolutionizing the design and optimization of biosynthetic pathways for drug development.

Computational Tools for Biosynthetic Pathway Prediction: A Guide for Drug Development and Synthetic Biology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the computational tools and methodologies revolutionizing the design and optimization of biosynthetic pathways for drug development. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and industry professionals, it explores the foundational databases and algorithms, details cutting-edge applications from retrosynthesis to machine learning, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents frameworks for the rigorous validation of predicted pathways. By synthesizing current capabilities and future directions, this guide serves as a roadmap for leveraging computational predictions to accelerate the creation of efficient microbial cell factories for high-value natural products and therapeutics.

The Data and Discovery Foundation: Mapping the Landscape of Biosynthetic Pathways

The reconstruction of metabolic pathways in completely sequenced organisms requires sophisticated computational tools and high-quality biological data [1]. Biological databases provide the foundational knowledge necessary for these tasks, storing detailed information on chemical compounds, biochemical reactions, and enzymes. In the context of computational biosynthetic pathway prediction, these resources enable researchers to move from genomic information to functional metabolic models [1] [2]. The effectiveness of computational methods for pathway design depends fundamentally on the quality and diversity of available biological data from several categories, including compounds, reactions/pathways, and enzymes [2]. This application note provides a comprehensive guide to these essential resources, highlighting their applications in predictive research and experimental design for drug development and metabolic engineering.

Biological databases can be broadly classified into three main categories based on their primary content focus: compound databases, reaction/pathway databases, and enzyme databases. Each category serves distinct yet complementary roles in biosynthetic pathway research. The table below summarizes key databases, their primary focus, and representative applications in computational research.

Table 1: Categorization of Essential Biological Databases for Biosynthetic Pathway Prediction

| Database Name | Primary Content | Key Features | Applications in Pathway Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem [2] [3] | Chemical compounds | 111+ million compounds; structures, properties, bioactivity | Foundational reference for metabolite identification |

| ChEBI [2] [4] | Chemical entities of biological interest | Curated small molecules; ontology-based classification | Standardized chemical data for reaction prediction |

| COCONUT [2] [3] | Natural products | 400,000+ open-access natural products | Expanding chemical space for novel pathway design |

| KEGG [1] [2] [4] | Pathways, compounds, enzymes | 372+ reference pathways; 15,000+ compounds | Reference pathway maps; organism-specific metabolism |

| MetaCyc [2] [4] [5] | Metabolic pathways and enzymes | 3,128+ experimentally elucidated pathways from 3,443 organisms | Reference for metabolic engineering and enzyme discovery |

| Reactome [2] [4] | Biological pathways | Curated, peer-reviewed human pathways | Context for drug target identification and validation |

| BRENDA [2] [6] [7] | Enzyme function and kinetics | Comprehensive enzyme kinetics; manual curation | Kinetic parameter integration for pathway feasibility |

| Rhea [2] [6] | Biochemical reactions | Expert-curated biochemical reactions with EC classification | Standardized reaction data for pathway assembly |

| UniProt [2] [6] | Protein sequences and function | Enzyme sequence-function relationships; cross-references | Gene-protein-reaction linking for pathway reconstruction |

Experimental Protocol: Database-Driven Biosynthetic Pathway Prediction

Principle and Scope

This protocol outlines a computational workflow for predicting novel biosynthetic pathways using the SubNetX algorithm, which combines constraint-based and retrobiosynthesis methods to design pathways for complex natural and non-natural compounds [8]. The method is particularly valuable for metabolic engineering and drug development applications where production of complex biochemicals requires balancing multiple metabolic inputs and outputs.

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Data Resources for Pathway Prediction

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Databases | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Databases | KEGG LIGAND, MetaCyc, Rhea, ATLASx, ARBRE | Provide known and predicted biochemical transformations |

| Compound Databases | PubChem, ChEBI, COCONUT | Supply chemical structures and properties for target molecules |

| Enzyme Databases | BRENDA, UniProt, PDB | Offer enzyme specificity, kinetics, and structural data |

| Host Metabolic Models | Genome-scale models (e.g., E. coli, yeast) | Provide native metabolic context for heterologous pathway integration |

| Computational Tools | SubNetX, PathPred, Pathway Tools | Execute pathway search, expansion, and feasibility analysis |

Procedure

Step 1: Reaction Network Preparation

- Input Definition: Define a network of elementally balanced biochemical reactions from databases such as KEGG LIGAND [1] [9] or MetaCyc [5]. For expanded chemical space, incorporate predicted biochemical reactions from resources like ATLASx, which contains over 5 million reactions [8].

- Target and Precursor Specification: Identify target compounds using PubChem [2] [3] or ChEBI [2] identifiers. Define precursor compounds based on the metabolic capabilities of the chosen host organism (e.g., E. coli central metabolites).

Step 2: Graph Search for Linear Core Pathways

- Similarity Searching: Perform global structure similarity search against KEGG COMPOUND using algorithms like SIMCOMP to identify structurally similar compounds [10].

- Transformation Pattern Matching: Execute local RDM pattern matching against the KEGG RPAIR database to identify plausible enzymatic transformations [10].

Step 3: Expansion and Extraction of Balanced Subnetworks

- Stoichiometric Expansion: Expand linear pathways to include required cosubstrates and connect byproducts to the host's native metabolism using constraint-based methods [8].

- Thermodynamic Validation: Assess energy requirements of proposed pathways using free energy data from MetaCyc [5] or calculated values.

Step 4: Integration into Host Metabolic Model

- Model Incorporation: Integrate the extracted subnetwork into a genome-scale metabolic model of the host organism (e.g., E. coli) using systems biology markup language (SBML).

- Stoichiometric Feasibility Testing: Apply flux balance analysis to verify that the host can produce the target compound while maintaining growth requirements.

Step 5: Pathway Ranking and Selection

- Multi-criteria Assessment: Rank feasible pathways based on yield, pathway length, enzyme specificity from BRENDA [6] [7], and thermodynamic feasibility.

- Minimal Reaction Set Identification: Use mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) to identify the minimum number of heterologous reactions required for production [8].

Application Notes

- Gap Filling: When pathway gaps exist, tools like PathPred can predict multi-step metabolic pathways by leveraging chemical transformation patterns from KEGG RPAIR [10].

- Enzyme Compatibility: Cross-reference predicted reactions with enzyme databases to identify potential enzyme candidates, considering organism-specific codon usage and expression requirements.

- Validation: For high-priority pathways, conduct in silico gene knockout simulations to assess pathway robustness and identify potential competing reactions.

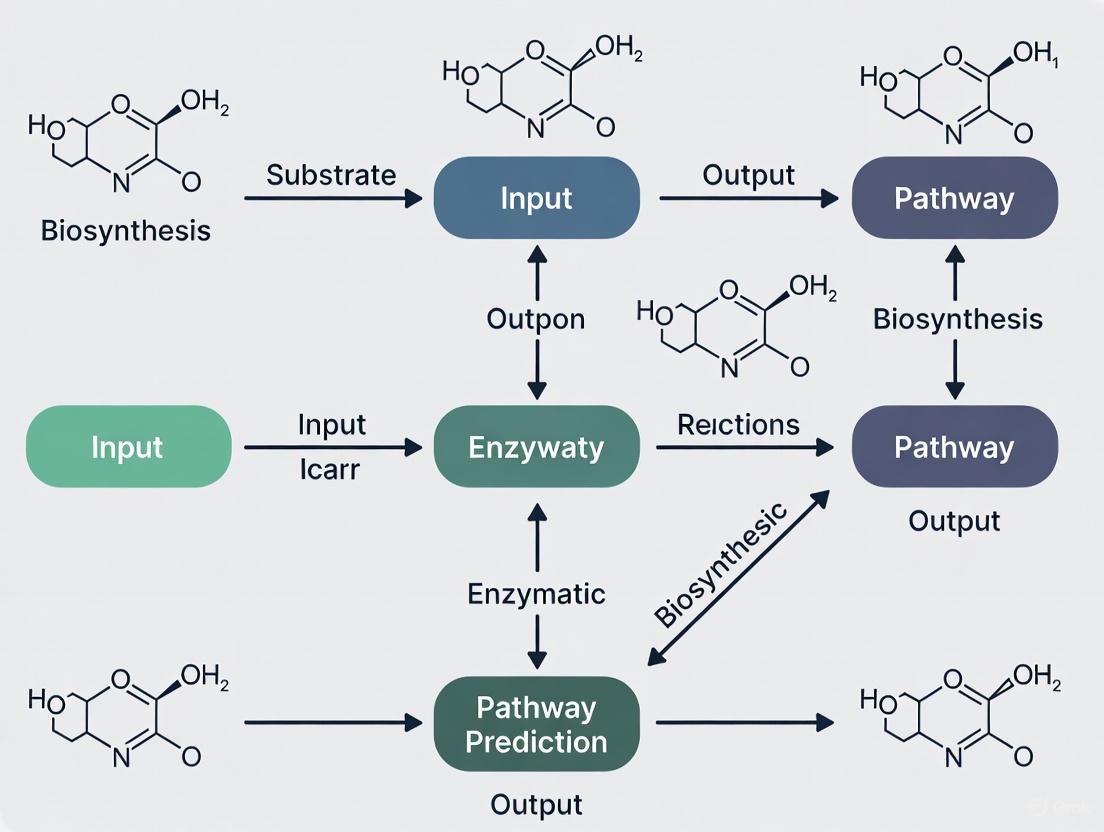

Database Integration in Pathway Prediction Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and data flow between different database types during a typical biosynthetic pathway prediction workflow:

Database Integration in Pathway Prediction

Specialized computational tools leverage these integrated database resources to enable novel pathway discovery. For example, PathPred employs a recursive algorithm that combines compound similarity searching with transformation pattern matching to predict multi-step metabolic pathways for both biodegradation and biosynthesis applications [10]. The tool systematically explores the biochemical reaction space by generating plausible intermediates and linking transformations to genomic data through enzyme annotation tools.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

Recent advances in deep learning algorithms are creating new opportunities for enhancing enzyme databases and pathway prediction capabilities. The exponential growth in published enzyme data presents challenges for manual curation, making machine readability and standardization increasingly important [6]. Tools like AlphaFold DB provide predicted protein structures that can help assess enzyme compatibility for novel reactions identified through tools like SubNetX [8].

Challenges and Standardization Efforts

A significant challenge in utilizing enzyme databases is the lack of data standardization across publications. Analysis has shown that 11-45% of papers omit critical experimental parameters such as temperature, enzyme concentration, or substrate concentration [6]. The STRENDA (Standards for Reporting Enzyme Data) initiative has been established to address these issues, with more than 55 international biochemistry journals having adopted these guidelines [6].

Biological databases covering compounds, reactions, and enzymes form an essential infrastructure for computational biosynthetic pathway prediction. The integration of these resources through algorithms like SubNetX and PathPred enables researchers to navigate the complex landscape of metabolic engineering with greater efficiency and success. As these databases continue to expand and improve through standardization efforts and artificial intelligence applications, they will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating the development of sustainable bioproduction platforms for pharmaceuticals and other valuable chemicals.

Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) are groups of clustered genes found in the genomes of bacteria, fungi, plants, and some animals that encode the biosynthetic machinery for specialized metabolites [11] [12]. These metabolites, also known as secondary metabolites, are not essential for basic growth and development but provide producing organisms with significant adaptive advantages, leading to compounds with diverse chemical structures and biological activities [13] [12]. The products of BGCs have tremendous biotechnological and pharmaceutical importance, serving as antibiotics, anticancer agents, immunosuppressants, herbicides, and insecticides [13] [14]. Traditional methods for discovering these bioactive compounds relied heavily on culturing microorganisms and extracting their metabolic products, which is time-consuming and often leads to the rediscovery of known compounds. The emergence of genome sequencing technologies and sophisticated computational tools has revolutionized this field, enabling researchers to directly mine genomic data for novel BGCs, a process known as genome mining [11] [13].

Computational prediction of BGCs has become a cornerstone of modern natural product discovery [11]. By applying bioinformatics tools to genome sequences, researchers can rapidly identify and annotate BGCs, prioritizing the most promising candidates for experimental characterization [11] [12]. This in silico approach has significantly accelerated the discovery pipeline. The advent of artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning and deep learning algorithms, has further enhanced the speed, precision, and predictive power of BGC mining tools [11]. These computational advances are framed within the broader context of synthetic biology, which aims not only to discover natural pathways but also to design new biosynthetic routes for valuable chemicals, both natural and non-natural [15] [16] [8]. This article provides a detailed introduction to the fundamental databases, computational tools, and standard protocols for predicting and analyzing BGCs, serving as a practical guide for researchers in the field.

Foundational Databases and Computational Tools

The computational prediction of BGCs relies on a robust infrastructure of curated databases and specialized software tools. Familiarity with these resources is a prerequisite for effective genome mining.

Essential Databases for BGC Prediction and Analysis

Table 1: Key Databases for BGC and Pathway Research

| Database Name | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| MIBiG (Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster) | Repository of experimentally characterized BGCs [12]. | Provides a standardized data format for BGC annotations, including genomic information, chemical structures, and biological activities of the metabolites [12]. Serves as a crucial gold-standard reference for training and validating prediction tools. |

| International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC) | Archives raw nucleotide sequences [12]. | Comprises GenBank (NCBI), European Nucleotide Archive (EBI-ENA), and DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ). Provides the primary genomic data used as input for BGC prediction tools. |

| ARBRE | Database of balanced biochemical reactions [8]. | A highly curated database of ~400,000 reactions, with a focus on industrially relevant aromatic compounds. Used by pathway design algorithms like SubNetX to extract feasible biosynthetic routes [8]. |

| ATLASx | Database of predicted biochemical reactions [8]. | One of the largest networks of predicted reactions, containing over 5 million entries. Used to fill knowledge gaps and propose novel pathways not yet observed in nature [8]. |

Core Computational Tools for BGC Prediction and Analysis

A wide array of computational tools has been developed to identify, annotate, and compare BGCs from genomic data.

Table 2: Core Computational Tools for BGC Prediction and Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH (antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis SHell) | The most widely used tool for BGC detection and annotation [13] [14]. | Identifies BGCs in genomic data and compares them to known clusters via KnownClusterBlast, ClusterBlast, and SubClusterBlast [13]. Considered the industry standard for initial genome mining. |

| BiG-SCAPE (Biosynthetic Gene Similarity Clustering and Prospecting Engine) | Correlates and classifies BGCs into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) [13]. | Analyzes the sequence similarity of BGCs identified by tools like antiSMASH. Groups BGCs into families based on user-defined similarity cutoffs (e.g., 10%, 30%), helping prioritize novel BGCs [13]. |

| SubNetX | Designs balanced biosynthetic pathways for complex chemicals [8]. | An algorithm that extracts reactions from databases and assembles stoichiometrically balanced subnetworks to produce a target biochemical. Integrates pathways into host metabolic models to rank them based on yield and feasibility [8]. |

| novoStoic2.0 | An integrated platform for de novo pathway design [17]. | A unified web-based framework that combines tools for estimating stoichiometry, designing synthesis pathways, assessing thermodynamic feasibility, and selecting enzymes for novel steps [17]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical relationship and sequence of using these key tools in a typical BGC analysis pipeline.

Application Notes: A Practical Protocol for BGC Discovery and Analysis

This section provides a detailed, citable protocol for identifying and analyzing BGC diversity in a set of bacterial genomes, based on a recent study investigating marine bacteria [13].

Experimental Workflow for BGC Discovery

The following diagram outlines the comprehensive experimental workflow, from genome retrieval to final analysis.

Detailed Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Bacterial Strain Selection and Genome Retrieval

- Objective: To acquire high-quality genomic data for analysis.

- Protocol:

- Select bacterial strains of interest based on ecological source or phylogenetic relevance. In the reference study, 199 strains from 21 marine bacterial species were selected [13].

- Retrieve genome sequences from public databases such as the NCBI database. Prefer complete genomes where available.

- For species without complete genomes, high-quality contig-level assemblies are acceptable. Record scientific names, accession numbers, genome assembly levels, genome size, and number of protein-coding genes in a spreadsheet (e.g., Supplementary Table S1) [13].

Step 2: BGC Prediction using antiSMASH

- Objective: To identify and perform initial annotation of BGCs in the target genomes.

- Protocol:

- Use the bacterial version of antiSMASH (version 7.0) to screen each genome [13] [14].

- Run the analysis with default detection settings. Ensure that the following modules are enabled:

KnownClusterBlast,ClusterBlast,SubClusterBlast, andPfamdomain annotation [13]. - Systematically compile the results into a spreadsheet (e.g., Excel). For each genome, record the total number of BGCs and their specific classifications (e.g., NRPS, T3PKS, betalactone, NI-siderophore) [13]. This compiled data is essential for downstream comparative analysis (e.g., Supplementary Table S2) [13].

Step 3: Phylogenetic Analysis

- Objective: To understand the evolutionary relationships among the studied strains and correlate phylogeny with BGC distribution.

- Protocol:

- Select a suitable genetic marker for robust phylogenetic reconstruction. The

rpoBgene is a well-established marker for this purpose due to its relatively conserved nature [13]. - Retrieve the corresponding gene sequences (e.g., 192 sequences) from the NCBI nucleotide database.

- Perform a multiple sequence alignment using a tool like ClustalW integrated into BioEdit software.

- Construct a phylogenetic tree using MEGA11 software. Use the Maximum Likelihood method with 1000 bootstrap replicates to assess branch support, keeping other parameters as default [13].

- Visualize and annotate the resulting tree (exported in Newick format) using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) platform. Annotate the tree with BGC data to explore evolutionary patterns in biosynthetic potential [13].

- Select a suitable genetic marker for robust phylogenetic reconstruction. The

Step 4: BGC Clustering and Network Analysis

- Objective: To group identified BGCs into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) based on sequence similarity.

- Protocol:

- Use BiG-SCAPE (Biosynthetic Gene Similarity Clustering and Prospecting Engine) version 2.0 for clustering [13].

- Provide the GenBank files of the BGCs of interest (e.g., all NI-siderophore BGCs predicted to produce vibrioferrin) as input.

- Run BiG-SCAPE to group BGCs into GCFs based on domain sequence similarity. The analysis can be interpreted at multiple similarity cutoffs. A 30% cutoff defines broad GCFs, while a more stringent 10% cutoff resolves fine-scale diversity within GCFs [13].

- Generate similarity networks and visualize them using Cytoscape version 3.10.3 [13]. This visualization helps in understanding the relationships and uniqueness of the BGCs.

Step 5: In-depth Comparative Analysis of Specific BGCs

- Objective: To perform a detailed genetic and structural variability analysis of a specific BGC type across different strains.

- Protocol (exemplified for NI-siderophore BGCs):

- Download the GenBank files for the target BGC regions (e.g., vibrioferrin-associated NI-siderophore BGCs) from the antiSMASH results.

- Import these nucleotide sequences into a sequence analysis software like Geneious Prime.

- Translate the nucleotide sequences to amino acid sequences.

- Perform multiple sequence alignments using tools like Clustal Omega with default settings.

- Annotate the alignments to identify conserved core biosynthetic genes and variable accessory genes, highlighting the structural plasticity of the BGC [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Materials

| Item / Resource | Function in BGC Analysis |

|---|---|

| antiSMASH 7.0 | Core detection engine for identifying BGC boundaries and predicting their types in a given genome [13] [14]. |

| BiG-SCAPE | Computational reagent for correlating BGCs based on sequence similarity, generating Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) for prioritization [13]. |

| MIBiG Database | Reference repository of known BGCs; essential for annotating and determining the novelty of predicted clusters via tools like antiSMASH's KnownClusterBlast [12]. |

| Cytoscape | Visualization platform for rendering similarity networks generated by BiG-SCAPE, allowing for intuitive exploration of relationships between BGCs [13]. |

| rpoB Gene Sequences | Genetic marker used as a reagent for constructing reliable phylogenetic trees to study the evolutionary context of BGC distribution [13]. |

| 4-Oxo cyclophosphamide-d8 | 4-Oxo cyclophosphamide-d8, MF:C7H13Cl2N2O3P, MW:283.12 g/mol |

| Antitubercular agent-11 | Antitubercular agent-11|Research Compound |

Integration with Broader Computational Pathway Prediction

The prediction of BGCs is a starting point. The broader field of computational biosynthetic pathway prediction aims to understand, engineer, and even design de novo biosynthetic routes [15] [8]. BGC predictors like antiSMASH discover pathways that exist in nature, while other computational tools are designed for pathway engineering and creation.

Retrobiosynthesis methods leverage multidimensional biosynthesis data to predict potential pathways for target compound synthesis [15]. Tools like novoStoic2.0 integrate retrobiosynthesis with thermodynamic evaluation (using dGPredictor) and enzyme selection (using EnzRank) to create a unified workflow for designing thermodynamically feasible pathways [17]. This is particularly valuable for producing compounds without known natural pathways. Furthermore, algorithms like SubNetX address the challenge of producing complex molecules that require branched pathways and balanced cofactor usage, moving beyond simple linear pathways to designs that integrate seamlessly with host metabolism for higher yields [8]. The integration of AI and machine learning is a common thread, enhancing both the prediction of natural BGCs and the design of novel pathways [11] [17].

Computational prediction of BGCs has become an indispensable component of modern natural product discovery and synthetic biology. The standardized protocols and tools outlined in this article, centered on powerful platforms like antiSMASH and BiG-SCAPE, provide researchers with a robust framework for decoding nature's biosynthetic blueprints. The field continues to evolve rapidly, driven by improvements in AI and the integration of genome mining with pathway design tools. This synergy allows scientists to not only discover the vast hidden potential of microbial secondary metabolism but also to rationally engineer it for the production of novel bioactive compounds and high-value chemicals, accelerating innovation in drug development and biotechnology.

The field of natural product discovery has undergone a fundamental transformation, moving from traditional bioactivity-guided isolation to data-driven genome mining strategies. This shift began in the early 2000s with the first sequenced Streptomyces bacterial genomes, which revealed that the vast majority of small molecules produced by microbes remained undiscovered [18]. Genome mining refers to the use of genomic sequence data to identify and predict genes encoding the production of novel compounds, harnessing the breadth of genetic information now available for hundreds of thousands of organisms in publicly accessible databases [18] [19]. Where traditional methods faced challenges of dereplication and frequent re-isolation of known compounds, modern genome mining enables targeted discovery of bioactive natural products by exploiting genetic signatures of biosynthetic enzymes [18]. The natural products research community has developed orthogonal genome mining strategies to target specific chemical features or biological properties of bioactive molecules using biosynthetic, resistance, or transporter proteins as "biosynthetic hooks" [18] [19]. This application note details the principles and protocols for implementing these approaches, framed within the broader context of computational tools for biosynthetic pathway prediction research.

Key Principles and Strategic Approaches

Bioactive Feature Targeting

Bioactive natural products often contain specific chemical features directly responsible for their biological activity. Genome mining can target these features by identifying enzymes responsible for their installation [18].

- Reactive Chemical Features: These include electrophilic, radical, or nucleophilic functional groups that often result in covalent binding to protein targets. Key examples include enediynes, β-lactones, and epoxyketones [18].

- Structural Binding Features: These features enable non-covalent binding to biological or chemical targets, from macromolecular proteins to small metal ions [18].

Table 1: Reactive Chemical Features and Their Biosynthetic Enzymes for Targeted Genome Mining

| Reactive Feature | Structure | Biosynthetic Enzymes | Mining Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enediyne | 9-10 membered ring with alkene flanked by alkynes | Polyketide Synthases (PKS) | Tiancimycin A discovery [18] |

| β-Lactone | Four-membered cyclic ester | β-Lactone synthetase, Thioesterase, Hydrolase | Large-scale mining efforts [18] |

| Epoxyketone | Three-membered cyclic ether adjacent to ketone | Flavin-dependent decarboxylase-dehydrogenase-monooxygenase | Proteasome inhibitor discovery [18] |

| Isothiocyanate | N=C=S group | Putative isonitrile synthase | Large-scale mining [18] |

Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Analysis

Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) are genomic loci containing all genes required for the biosynthesis of a natural product. Several orthogonal strategies have been developed for BGC analysis:

- Biosynthetic Protein Targeting: Using conserved biosynthetic enzymes as hooks to identify BGCs encoding specific compound families [18].

- Resistance Protein Targeting: Exploiting the fact that organisms protect themselves from their own bioactive compounds, making resistance genes effective markers for adjacent BGCs [18].

- Transport Protein Targeting: Utilizing transporter proteins associated with bioactive compound secretion as indicators of nearby BGCs [18].

Essential Bioinformatics Tools and Databases

Genome Mining Software Platforms

The effectiveness of genome mining depends on specialized bioinformatics tools that can systematically discover hidden BGCs.

Table 2: Essential Bioinformatics Tools for Genome Mining

| Tool | Function | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH 7.0 | BGC identification & annotation | Predicts BGCs across >40 cluster types | Hidden Markov Models, Rule-based scoring [20] |

| DeepBGC | BGC identification using machine learning | Identifies orphan clusters in under-explored phyla | BiLSTM, Random Forests [20] |

| PRISM 2.0 | Ribosomal peptide & hybrid pathway prediction | RiPPs and polyketide-NRPS hybrids | Structural prediction of natural products [20] |

| RIPPER | RiPPs prediction | Ribosomally synthesized peptides | Standardized prediction based on RBS [20] |

| SubNetX | Balanced subnetwork extraction | Pathway design for complex chemicals | Constraint-based optimization [8] |

| GNPS | Metabolomics & molecular networking | MS/MS data analysis & community sharing | Feature-based molecular networking [20] |

Critical Databases for Pathway Prediction

Computational biosynthetic pathway design depends on the quality and diversity of available biological data from several categories [2].

Table 3: Essential Databases for Biosynthetic Pathway Design

| Data Category | Database | Primary Function | Content Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | PubChem | Chemical compound repository | 119 million compound records [2] |

| NPAtlas | Natural products repository | Curated natural products with annotated structures [2] | |

| LOTUS | Natural products database | Chemical, taxonomic, and spectral data integration [2] | |

| Reactions/Pathways | KEGG | Pathway database | Genomic, chemical, and systemic functional information [2] |

| MetaCyc | Metabolic pathways & enzymes | Biochemical reactions across organisms [2] | |

| Reactome | Biological pathways | Curated molecular events and interactions [2] | |

| Rhea | Biochemical reactions | Enzyme-catalyzed reactions with chemical structures [2] | |

| Enzymes | UniProt | Protein information database | Protein structure, function, and evolution [2] |

| BRENDA | Comprehensive enzyme database | Enzyme functions, structures, and mechanisms [2] | |

| AlphaFold DB | Protein structure prediction | AI-predicted protein structures [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Integrated Genome Mining Protocol for Bioactive Natural Products

This protocol outlines a comprehensive workflow for discovering novel bioactive natural products through integrated genomic and metabolomic analysis.

Phase 1: Genomic DNA Sequencing and Assembly

- Step 1.1: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from microbial strains using standard kits or CTAB methods.

- Step 1.2: Perform whole-genome sequencing using PacBio HiFi (long-read, accuracy >99.9%) or Illumina platforms (short-read) for complementary coverage [20].

- Step 1.3: Assemble sequences using appropriate assemblers (Canu for long-read, SPAdes for short-read) and annotate with Prokka or RAST.

- Step 1.4: Quality assessment: Validate assembly completeness with BUSCO, aiming for >95% complete single-copy genes.

Phase 2: In Silico BGC Identification and Analysis

- Step 2.1: Identify BGCs using antiSMASH 7.0 with default parameters. This tool integrates Hidden Markov Models and identifies >40 BGC types [20].

- Step 2.2: Prioritize BGCs based on:

- Step 2.3: For RiPPs analysis, use RiPPer for precursor peptide prediction and SPECO (short peptide and enzyme co-localization) for genome mining of RiPP BGCs [20].

Phase 3: Metabolomic Correlative Analysis

- Step 3.1: Culture producing strains under multiple conditions using OSMAC (One Strain Many Compounds) approach [20].

- Step 3.2: Extract metabolites with organic solvents (ethyl acetate, methanol) of varying polarities.

- Step 3.3: Analyze extracts using HRMS (Orbitrap, TOF, or FT-ICR systems) with LC separation [20].

- Step 3.4: Process MS data with MZmine3 and create molecular networks using GNPS platform with FBMN (Feature-Based Molecular Networking) [20].

Phase 4: Compound Isolation and Structure Elucidation

- Step 4.1: Scale up cultivation of promising strains (4-20L) based on genomic and metabolomic correlation.

- Step 4.2: Fractionate extracts using vacuum liquid chromatography followed by HPLC (C18 or phenyl-hexyl columns).

- Step 4.3: Monitor fractions for target compounds using HRMS and bioactivity screening.

- Step 4.4: Ispure compounds using preparative HPLC and determine structures using:

Phase 5: Validation and Engineering

- Step 5.1: Confirm biosynthetic origins through heterologous expression in model hosts (S. albus J1074, E. coli) [20].

- Step 5.2: Implement CRISPRi-mediated pathway activation for silent BGCs [20].

- Step 5.3: Perform biochemical characterization of key enzymes.

Figure 1: Integrated Genome Mining Workflow for Bioactive Natural Product Discovery

Targeted Genome Mining for P450-Modified RiPPs

This specialized protocol focuses on discovering cytochrome P450-modified ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs), which represent a growing class of bioactive natural products with diverse macrocyclic structures [20].

Step 1: Sequence Database Mining

- Query NCBI and JGI databases using characterized P450 enzymes (BytO, CitB, TrpB) as references via BlastP [20].

- Perform EFI-EST analysis for generating sequence similarity networks (SSNs) [20].

- Apply length filtering to obtain non-redundant P450 sequences.

Step 2: RiPP BGC Identification

- Use RiPPer to predict precursor peptide sequences adjacent to P450 enzymes [20].

- Focus on precursors with multiple conserved aromatic amino acids.

- Classify identified gene clusters into categories using SSN analysis.

Step 3: Multi-dimensional Bioinformatics Analysis

- Apply multilayer sequence similarity network (MSSN) for functional correlation analysis [20].

- Utilize AlphaFold-Multimer for predicting protein complex structures [20].

- Validate predictions by assessing conserved binding modes where precursor peptides embed C-termini within P450 pockets.

Step 4: Heterologous Expression and Characterization

- Clone selected BGCs (e.g., kst, mci, scn, sgr) into expression vectors [20].

- Express in suitable hosts (E. coli or S. albus J1074) [20].

- Purify and characterize resulting macrocyclic peptides (e.g., kitasatide, micitide, strecintide) using HRMS and NMR [20].

Figure 2: Specialized Workflow for Discovery of P450-Modified RiPPs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of genome mining requires both computational tools and laboratory reagents. The following table details essential research reagent solutions for genome mining experiments.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Genome Mining Experiments

| Category | Reagent/Kit | Specific Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | CTAB-based methods | High-quality genomic DNA from microbes | Optimal for GC-rich actinomycetes [20] |

| Commercial kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy) | Rapid standardized DNA extraction | Suitable for high-throughput processing [20] | |

| Sequencing | PacBio HiFi chemistry | Long-read sequencing (>99.9% accuracy) | Ideal for BGC assembly due to long repeat regions [20] |

| Illumina NovaSeq | Short-read high-throughput sequencing | Complementary coverage with PacBio [20] | |

| Cloning & Expression | Gibson Assembly | Vector construction for heterologous expression | Seamless cloning of large BGCs [20] |

| E. coli expression strains (BL21, etc.) | Heterologous production | Limited for complex natural products [20] | |

| Streptomyces expression strains (S. albus J1074) | Actinobacterial natural production | Preferred host for actinomycete BGCs [20] | |

| Chromatography | C18 reverse-phase columns | Metabolite separation | Various scales from analytical to preparative [20] |

| Sephadex LH-20 | Size exclusion chromatography | Desalting and fractionation of crude extracts [20] | |

| Analytical Standards | Internal standards for HRMS | Mass calibration | ESI-L low concentration tuning mix for Orbitrap [20] |

| NMR solvents (DMSO-d6, CD3OD) | Structure elucidation | Anhydrous for sensitive natural products [20] | |

| 2'-Deoxy-8-methylamino-adenosine | 2'-Deoxy-8-methylamino-adenosine, MF:C11H16N6O3, MW:280.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 1-Chloro-4-methoxybenzene-d4 | 1-Chloro-4-methoxybenzene-d4, MF:C7H7ClO, MW:146.61 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implementation of the SubNetX Algorithm for Pathway Design

The SubNetX algorithm represents a cutting-edge approach for designing pathways for complex biochemical production by combining constraint-based and retrobiosynthesis methods [8].

Protocol: SubNetX Implementation for Balanced Pathway Design

Step 1: Reaction Network Preparation

- Compile database of elementally balanced reactions (e.g., ARBRE database with ~400,000 reactions) [8].

- Define target compounds and precursor compounds based on host metabolism.

- Set user-defined parameters for search constraints.

Step 2: Graph Search for Linear Core Pathways

- Execute graph search from precursor compounds to target compounds.

- Identify potential linear pathways connecting precursors to targets.

Step 3: Expansion and Subnetwork Extraction

- Expand network to link cosubstrates and byproducts to native metabolism.

- Extract balanced subnetwork where all cofactors are connected to host metabolism.

- For gaps in biochemical knowledge, supplement with predicted reaction databases (e.g., ATLASx with 5+ million reactions) [8].

Step 4: Host Integration

- Integrate subnetwork into genome-scale metabolic model of host organism (e.g., E. coli).

- Validate stoichiometric feasibility using constraint-based optimization.

Step 5: Pathway Ranking and Selection

- Apply mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) to identify minimal sets of essential reactions.

- Rank feasible pathways based on yield, enzyme specificity, and thermodynamic feasibility.

- Select optimal pathways for experimental implementation.

Figure 3: SubNetX Workflow for Balanced Biosynthetic Pathway Design

Genome mining has fundamentally transformed natural product discovery from a serendipity-driven process to a targeted, data-driven endeavor. By leveraging biosynthetic hooks such as enzymes installing bioactive features, resistance proteins, or transporter proteins, researchers can specifically target BGCs with a high probability of encoding previously undiscovered bioactive compounds [18]. The integration of multi-omics data—genomics revealing a strain's biosynthetic potential and metabolomics capturing actual secondary metabolites—enables comprehensive analysis from genes to chemical phenotypes [20].

Future developments in genome mining will likely focus on several key areas. Machine learning and artificial intelligence will play increasingly important roles in BGC prediction and prioritization, as demonstrated by tools like DeepBGC [20]. The exploration of underexplored taxonomic groups, such as verrucose microbes, represents another frontier for novel natural product discovery [20]. Additionally, the continued development of algorithms like SubNetX that integrate constraint-based methods with retrobiosynthesis will enhance our ability to design pathways for complex natural and non-natural compounds [8]. As these computational methods advance alongside experimental techniques such as CRISPRi activation of silent BGCs and ultra-sensitive analytical technologies, the pace of bioactive natural product discovery will continue to accelerate, reinforcing the critical role of genome mining in drug discovery and development.

Metabolism is the fundamental chemical process that sustains life, providing both the energy and the molecular building blocks for cellular growth and reproduction. For researchers in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, understanding the core metabolic pathways and their key precursor metabolites is essential for designing efficient microbial cell factories. These core pathways, which carry relatively high flux and are central to maintaining and reproducing the cell, provide the precursors and energy required for engineered metabolic pathways [21] [22]. Computational tools have become indispensable in elucidating, predicting, and optimizing these biosynthetic pathways, enabling the rational design of biocatalytic systems for producing value-added compounds, from pharmaceuticals to sustainable chemicals [15] [23] [8]. This application note explores the core metabolic building blocks and presents integrated computational-experimental protocols for biosynthetic pathway design and analysis, framed within the context of advanced computational prediction tools.

Core Metabolic Pathways and Their Key Precursors

In a typical bacterial cell, among thousands of enzymatic reactions, only a few hundred form the metabolic pathways essential for producing energy carriers and biosynthetic precursors. These central metabolic subsystems are responsible for generating the fundamental molecular building blocks from which all complex cellular components are assembled [21] [22].

Table 1: Essential Biosynthetic Precursors and Their Metabolic Roles

| Precursor Metabolite | Primary Metabolic Pathways | Key Cellular Functions | Engineering Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose-6-phosphate | Glycolysis, Pentose phosphate pathway | Entry point for carbohydrate metabolism; produces NADPH and pentose phosphates | Precursor for nucleotide synthesis and aromatic amino acids |

| Pyruvate | Glycolysis, Anaplerotic reactions | Key junction metabolite linking glycolysis to TCA cycle | Branch point for organic acid production and amino acid synthesis |

| Acetyl-CoA | Pyruvate dehydrogenase, Fatty acid oxidation | Central to energy metabolism and biosynthetic reactions | Key precursor for fatty acids, polyketides, and isoprenoids |

| Oxaloacetate | TCA cycle, Gluconeogenesis | Amphibolic intermediate connecting carbon and nitrogen metabolism | Precursor for aspartate family amino acids |

| α-Ketoglutarate | TCA cycle, Amino acid metabolism | Connects carbon and nitrogen metabolism | Precursor for glutamate family amino acids |

| 3-Phosphoglycerate | Glycolysis, Serine biosynthesis | Intermediate in carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism | Precursor for serine, glycine, and cysteine |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate | Glycolysis, Shikimate pathway | High-energy glycolytic intermediate | Precursor for aromatic amino acids and phenylpropanoids |

| Ribose-5-phosphate | Pentose phosphate pathway | Sugar phosphate backbone for nucleotides | Essential for nucleotide and cofactor synthesis |

| Erythrose-4-phosphate | Pentose phosphate pathway | Four-carbon sugar phosphate | Combined with PEP for shikimate pathway |

The iCH360 model of Escherichia coli core and biosynthetic metabolism exemplifies a manually curated "Goldilocks-sized" model that focuses specifically on these central pathways. This compact model includes all routes required for energy production and biosynthesis of main biomass building blocks – amino acids, nucleotides, and fatty acids – while representing the conversion of these precursors into more complex biomass components through a consolidated biomass reaction [22]. Such intermediate-sized models strike a balance between the comprehensive coverage of genome-scale models and the precision and interpretability of smaller kinetic models, making them particularly valuable for pathway design and analysis [21] [22].

Computational Frameworks for Pathway Prediction and Design

Advancements in computational biology have produced sophisticated tools and algorithms that leverage biochemical knowledge to predict and design biosynthetic pathways. These approaches can be broadly categorized into database-driven methods, retrosynthesis algorithms, stoichiometric approaches, and machine learning techniques.

Database-Driven and Retrosynthesis Approaches

Tools such as gapseq employ informed prediction of bacterial metabolic pathways by leveraging curated reaction databases and novel gap-filling algorithms. This approach uses a database derived from ModelSEED biochemistry, comprising 15,150 reactions (including transporters) and 8,446 metabolites, to reconstruct accurate metabolic models [24]. The software demonstrates a 53% true positive rate in predicting enzyme activities, significantly outperforming other automated reconstruction tools like CarveMe (27%) and ModelSEED (30%) [24].

Retrosynthesis methods represent another powerful approach, leveraging multi-dimensional biosynthesis data to predict potential pathways for target compound synthesis. These methods work backward from the target molecule to identify plausible biochemical routes using known enzymatic reactions [15] [23]. When combined with enzyme engineering based on data mining to identify or design enzymes with desired functions, these approaches significantly enhance the efficiency and accuracy of biosynthetic pathway design in synthetic biology [23].

Constraint-Based and Hybrid Approaches

The SubNetX algorithm represents an innovative hybrid approach that combines the strengths of constraint-based modeling and retrobiosynthesis methods. This computational pipeline extracts reactions from biochemical databases and assembles balanced subnetworks to produce target biochemicals from selected precursor metabolites, energy currencies, and cofactors [8]. The algorithm follows a five-step workflow:

- Reaction network preparation using elementally balanced reactions

- Graph search of linear core pathways from precursors to targets

- Expansion and extraction of a balanced subnetwork

- Integration of the subnetwork into the host metabolism

- Ranking of feasible pathways based on yield, length, and other criteria [8]

This approach has been successfully applied to 70 industrially relevant natural and synthetic chemicals, demonstrating its ability to identify viable pathways with higher production yields compared to linear pathways [8].

Diagram 1: SubNetX pathway design workflow. This diagram illustrates the computational pipeline for extracting balanced biosynthetic subnetworks, from target compound identification to feasible pathway ranking.

Machine Learning in Pathway Prediction

Machine learning techniques are increasingly applied to predict and reconstruct metabolic pathways, offering state-of-the-art performance in handling rapidly increasing volumes of biological data. These approaches can be categorized into several applications:

- Pathway Prediction: Identifying metabolic pathways that specific compounds belong to, using methods like hybrid random forest and graph convolution neural networks [25].

- Dynamics Prediction: Forecasting metabolic pathway dynamics from time-series multiomics data, outperforming traditional kinetic models in predicting metabolite concentrations [26].

- Component Prediction: Predicting individual elements of metabolic pathways, including enzymes, metabolites, and reactions, through various supervised learning approaches [25].

A notable machine learning formulation frames metabolic dynamics prediction as a supervised learning problem, where the function f that describes metabolite time derivatives based on metabolite and protein concentrations is learned directly from experimental data, without presuming specific kinetic relationships [26].

Integrated Protocol for Metabolic Pathway Analysis and Subtyping

This section presents a detailed protocol for analyzing metabolic pathways and performing metabolism-based stratification, adapted from breast tumor metabolic subtyping methodologies [27]. The protocol converts gene-level information into pathway-level information and identifies distinct metabolic subtypes.

Computational Protocol for Metabolic Pathway Analysis

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathifier | R Algorithm | Calculates pathway deregulation scores (PDS) | Converts gene expression to pathway-level information |

| NbClust | R Package | Determines optimal number of clusters in dataset | Metabolic subtype identification |

| Consensus Clustering | GenePattern Tool | Performs robust clustering analysis | Validates metabolic subtypes |

| Escher | Visualization Tool | Creates metabolic maps for network visualization | Pathway mapping and flux distribution display |

| COBRApy | Python Toolbox | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | Flux balance analysis and metabolic modeling |

| gapseq | Reconstruction Tool | Automated metabolic network reconstruction | Genome-scale model building from sequence data |

| SubNetX | Python Algorithm | Balanced subnetwork extraction and pathway ranking | Design of biosynthetic pathways for target compounds |

Protocol Steps:

Input File Preparation (Timing: 30 min)

- Prepare pre-processed normalized gene expression data

- Obtain genesets representing metabolic pathways (e.g., 90 metabolic pathways represented by 1,454 genes)

- Create a file containing expression values of all genes in the genesets [27]

Pathway Deregulation Scoring with Pathifier (Timing: 3 h)

- Load required R packages and input files:

- Process genesets and calculate minimum standard deviation:

- Run Pathifier to calculate Pathway Deregulation Scores (PDS):

- PDS quantifies the extent of deviation of each sample from normal reference, converting gene-level information to pathway-level information [27]

Clustering Analysis for Metabolic Subtyping (Timing: 2 h)

- Use NbClust to determine the optimal number of clusters:

- Perform consensus clustering to validate metabolic subtypes using the GenePattern online tool

- Apply k-means clustering with the determined optimal cluster number [27]

Machine Learning for Signature Identification (Timing: 10 min setup + variable runtime)

- Implement machine learning in Python using Google Colab or Jupyter Notebook

- Use SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) for feature importance analysis

- Apply PAMR (Prediction Analysis for Microarrays) to develop subtype-specific gene signatures [27]

Diagram 2: Metabolic subtyping protocol workflow. This diagram outlines the computational steps from gene expression data to metabolic subtype identification and signature development.

Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Drug Development

The integration of core metabolic pathway knowledge with computational design tools enables numerous applications in biotechnology and pharmaceutical development.

Engineering Microbial Cell Factories

Computational pathway design tools have been successfully applied to engineer microorganisms for producing valuable compounds. For example, SubNetX has been used to design pathways for 70 industrially relevant natural and synthetic chemicals, including complex pharmaceuticals [8]. These approaches allow researchers to identify pathways with higher yields than naturally occurring routes by exploring biochemical spaces beyond natural metabolism.

The iCH360 model demonstrates particular utility in enzyme-constrained flux balance analysis, elementary flux mode analysis, and thermodynamic analysis – all essential techniques for predicting and optimizing metabolic engineering strategies [22]. By focusing on central metabolism while maintaining connectivity to biosynthesis pathways, such models enable more realistic simulations of metabolic flux distributions under physiological constraints.

Nonnatural Pathway Design for Novel Compounds

For compounds without known natural biosynthetic pathways, computational tools enable the design of fully nonnatural metabolic routes. Template-based and template-free methods allow researchers to create pathways incorporating novel reactions, enabling efficient de novo synthesis of valuable compounds not produced in nature [16]. These approaches have been used to design pathways for compounds such as 2,4-dihydroxybutanoic acid and 1,2-butanediol, expanding the scope of biotransformation beyond natural metabolism.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, challenges remain in biosynthetic pathway design. Automated reconstructions sometimes generate biologically unrealistic predictions or miss essential metabolic functions [24]. Integrating mechanistic details including thermodynamics and kinetics is crucial for enhancing prediction reliability [8]. Furthermore, implementing nonnatural pathways may introduce new challenges such as increased metabolic burden and toxic intermediate accumulation [16].

Future developments will likely focus on better integration of machine learning methods with constraint-based modeling, improved database curation, and enhanced accounting for cellular regulation and compartmentalization. As computational tools continue to evolve, they will further accelerate the design-build-test cycle in metabolic engineering, enabling more efficient production of valuable chemicals and pharmaceuticals.

From Prediction to Production: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

The discovery and sustainable production of complex molecules, particularly natural products (NPs) and their derivatives, are crucial for drug development. Retrosynthesis, a concept with a long history in chemistry, involves deconstructing a target molecule into simpler, available precursors [28]. When applied to biological systems as retro-biosynthesis, it provides a powerful strategy for designing and reconstructing biosynthetic pathways in microbial hosts, offering a route to molecules that are difficult to obtain by extraction or total chemical synthesis [29] [28]. This approach aligns with the principles of green chemistry, enabling more environmentally friendly production processes [28].

The complexity of this task has been greatly aided by the advent of computational tools. Artificial intelligence (AI) is driving new frontiers in synthesis planning, using methods that can be broadly categorized as template-based (relying on libraries of known biochemical reaction rules) or template-free (using generative AI models to predict novel transformations) [28] [30]. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for three leading computational tools—BNICE.ch, RetroPath2.0, and BioNavi-NP—that exemplify these approaches and have demonstrated significant utility in the field of computational biosynthetic pathway prediction.

The landscape of computational tools for retrosynthesis is diverse, with each platform employing distinct strategies and algorithms. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of BNICE.ch, RetroPath2.0, and BioNavi-NP.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Retrosynthesis Tools

| Tool | Primary Approach | Core Algorithm/Model | Key Application | Database Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNICE.ch [29] | Template-based | Generalized enzymatic reaction rules | Expansion of heterologous pathways to natural product derivatives | KEGG [29] |

| RetroPath2.0 [31] | Template-based | Generalized reaction rules & workflow automation | Retrosynthesis from chassis to target; explores enzyme promiscuity | Custom RMN [31] |

| BioNavi-NP [30] | Template-free / Hybrid | Transformer neural networks & AND-OR tree search | Biosynthetic pathway prediction for NPs and NP-like compounds | BioChem, USPTO [30] |

BNICE.ch operates by applying generalized enzymatic reaction rules to systematically explore the biochemical vicinity of a known pathway. In one application, it expanded the noscapine biosynthetic pathway for four generations, creating a network of 4,838 compounds and 17,597 reactions, which was then trimmed to 1,518 relevant benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIAs) for further analysis [29]. In contrast, BioNavi-NP uses a deep learning model. An ensemble of four transformer models, trained on a combined set of 31,710 biosynthetic reactions and 62,370 NP-like organic reactions, achieved a top-10 single-step prediction accuracy of 60.6%, significantly outperforming conventional rule-based approaches [30]. RetroPath2.0 distinguishes itself as an automated open-source workflow that performs retrosynthesis searches from a defined microbial chassis to a target molecule, streamlining the design-build-test-learn pipeline for metabolic engineers [31].

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Pathway Expansion with BNICE.ch for Analogue Production

This protocol outlines the computational workflow to expand a heterologous biosynthetic pathway for the production of novel pharmaceutical compounds, as demonstrated for the noscapine pathway [29].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

- Biosynthetic Pathway: A defined pathway (e.g., the 17-metabolite noscapine pathway from Papaver somniferum).

- Database Resources: KEGG for biochemical data and template generation [29].

- Citation/Patent Data: Sources like PubMed and patent repositories for compound ranking.

2. Procedure 1. Network Expansion: Apply BNICE.ch's generalized enzymatic reaction rules iteratively to each intermediate in the native pathway. In the referenced study, this was done for four generations [29]. 2. Network Trimming: Filter the generated network to focus on chemically relevant space. For BIAs, this required retaining only compounds containing the 1-benzylisoquinoline scaffold (Câ‚₆Hâ‚₃N) [29]. 3. Compound Ranking: Rank the filtered list of candidate compounds based on popularity, defined as the sum of scientific citations and patents, to identify high-interest targets [29]. 4. Pathway Feasibility Filtering: Apply filters to prioritize candidates for experimental testing. Criteria include: * Thermodynamic feasibility of the pathway. * Availability of enzyme candidates with similar native functions. * The derivative being only one enzymatic step from a native pathway intermediate [29]. 5. Enzyme Candidate Prediction: Use a complementary tool like BridgIT to identify enzymes capable of catalyzing the desired novel transformation on the pathway intermediate [29].

3. Expected Outcomes The workflow is designed to output a shortlist of high-value target molecules (e.g., the analgesic (S)-tetrahydropalmatine was identified from the noscapine pathway) alongside specific enzyme candidates for experimental testing [29].

Diagram 1: BNICE.ch computational workflow for pathway expansion.

Protocol: Multi-step Retrosynthesis with BioNavi-NP

This protocol describes the use of BioNavi-NP for predicting complete biosynthetic pathways for natural products from simple building blocks [30].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

- Target Molecule: The SMILES string of the natural product or NP-like compound.

- Training Data: Curated datasets of biosynthetic reactions (e.g., BioChem with 33,710 unique pairs) and NP-like organic reactions (e.g., USPTO_NPL with 62,370 reactions) for model training [30].

- Enzyme Prediction Tools: Integrated tools like Selenzyme or E-zyme 2 for candidate enzyme mapping [30].

2. Procedure 1. Model Training (Pre-requisite): Train an enhanced molecular Transformer neural network on a combined dataset of biosynthetic and NP-like organic reactions. Using an ensemble of models is recommended for improved robustness [30]. 2. Single-Step Retrosynthesis: For a target molecule, the transformer model generates a ranked list of candidate precursor pairs. 3. Multi-Step Pathway Planning: Employ an AND-OR tree-based planning algorithm to navigate the combinatorial search space. The algorithm iteratively applies the single-step model to break down the target into simpler precursors until known building blocks are reached [30]. 4. Pathway Ranking: The proposed pathways are sorted and ranked based on computational cost, pathway length, and organism-specific enzyme availability [30]. 5. Enzyme Assignment: For each biosynthetic step in the proposed routes, use integrated enzyme prediction tools to suggest plausible enzymes [30].

3. Expected Outcomes The tool successfully identifies biosynthetic pathways for a high percentage of test compounds (90.2% in one test set of 368 compounds) and can recover reported building blocks with high accuracy (72.8%) [30]. The results are visualized on an interactive website.

Diagram 2: BioNavi-NP workflow for multi-step biosynthetic pathway prediction.

The following table details essential computational reagents and their functions for conducting retrosynthesis analyses.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Retrosynthesis

| Category | Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Software Tools | BNICE.ch [29] | Applies generalized reaction rules for pathway expansion and derivative identification. |

| RetroPath2.0 [31] | Automated workflow for retrosynthesis from a chassis organism to a target molecule. | |

| BioNavi-NP [30] | Predicts biosynthetic pathways using transformer AI and AND-OR tree search. | |

| Reaction Databases | KEGG [29] | Source of known enzymatic reactions and metabolic pathways for template generation. |

| BKMS [32] | Curated database of enzyme-catalyzed reactions for training retrosynthesis models. | |

| MetaCyc [33] | Database of metabolic pathways and enzymes used in pathway reconstruction. | |

| Supporting Tools | BridgIT [29] | Predicts enzyme candidates for a novel reaction based on structural similarity. |

| Selenzyme [30] | Predicts and ranks potential enzymes for a given biochemical reaction. |

Computational tools for retrosynthesis and de novo pathway design have become indispensable in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. As demonstrated, BNICE.ch is powerful for systematically exploring the chemical space around a known pathway to generate valuable derivatives. RetroPath2.0 provides a robust, automated workflow for connecting a target molecule to a host's native metabolism. BioNavi-NP represents a state-of-the-art template-free approach, leveraging deep learning to elucidate complex biosynthetic pathways for natural products with high accuracy.

The integration of these tools, from template-based to AI-driven, is reshaping the design and optimization of bioproduction pipelines. Future advancements will likely involve more sophisticated hybrid models that seamlessly combine enzymatic and synthetic chemistry, further bridging the gap between computational prediction and practical microbial synthesis for drug development and beyond [32] [28].

The design of efficient biosynthetic pathways is a cornerstone of synthetic biology, enabling the sustainable production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and value-added chemicals. However, this process traditionally involves a series of disjointed tasks—pathway discovery, thermodynamic feasibility analysis, and enzyme selection—often performed using separate computational tools. This fragmentation can lead to inconsistencies and hinder the transition from in silico design to experimental implementation. To address these challenges, novoStoic2.0 emerges as an integrated platform that unifies pathway synthesis, thermodynamic evaluation, and enzyme selection into a single, streamlined workflow [17] [34]. Developed as part of the AlphaSynthesis platform, this framework is designed to construct thermodynamically viable, carbon/energy balanced biosynthesis routes, while also providing actionable insights for enzyme re-engineering, thereby accelerating the development of sustainable biotechnological solutions [35].

novoStoic2.0 is a unified, web-based interface built on a Streamlit-based Python framework [17] [34]. It seamlessly integrates four distinct computational tools into a cohesive workflow, moving from a target molecule to an experimentally actionable pathway design.

The platform's core integration involves mapping data between major biological databases. It primarily utilizes the MetaNetX database, which provides a foundation of 23,585 balanced biochemical reactions and 17,154 molecules for pathway design [17] [34]. To enable thermodynamic analysis and enzyme selection, a critical mapping step connects these MetaNetX entries to their corresponding counterparts in the KEGG and Rhea databases. For novel molecules or reactions absent from standard databases, the platform uses InChI and SMILES string representations to facilitate analysis, ensuring that even non-catalogued steps can be evaluated and assigned potential enzyme candidates [34].

Table 1: Core Tools Integrated within novoStoic2.0

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Inputs | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| optStoic | Estimates optimal overall stoichiometry for a target conversion [34] | Source & target molecule IDs (MetaNetX/KEGG); Co-substrates/co-products [34] | Balanced overall reaction stoichiometry maximizing theoretical yield [34] |

| novoStoic | Designs de novo biosynthetic pathways [17] [34] | Overall stoichiometry (from optStoic); Max number of steps & pathways [34] | Multiple pathway designs connecting source to target, including novel steps [17] |

| dGPredictor | Estimates standard Gibbs energy change (ΔG'°) of reaction steps [17] [34] | KEGG reaction ID or InChI/SMILES for novel molecules [34] | Thermodynamic feasibility assessment for each reaction in a pathway [17] |

| EnzRank | Ranks enzyme candidates for novel reaction steps [17] [34] | Amino acid sequence & substrate (KEGG ID or SMILES) [34] | Probability score for enzyme-substrate compatibility; Rank-ordered list of enzyme candidates [34] |

Application Note: Implementing the novoStoic2.0 Workflow

This section provides a detailed protocol for using novoStoic2.0 to design a biosynthetic pathway, using the antioxidant hydroxytyrosol as a representative case study [17].

The following diagram, generated using DOT language, illustrates the integrated, step-by-step workflow from defining a production objective to selecting enzymes for implementation.

Protocol and Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Define Objective and Input Molecules

- Action: Navigate to the novoStoic2.0 web interface (http://novostoic.platform.moleculemaker.org/) [17].

- Input Specification:

- Source Molecule: Identify a suitable precursor (e.g., a central metabolic intermediate or a specified starting compound). Input using its MetaNetX or KEGG compound ID.

- Target Molecule: Input "hydroxytyrosol" using its appropriate database identifier.

- Co-substrates/Co-products: Optionally specify any required cofactors (e.g., NADH, ATP) or byproducts to be considered in the overall mass balance [34].

Step 2: Determine Optimal Stoichiometry with optStoic

- Action: Run the optStoic tool as a standalone module or as the first step in the integrated workflow.

- Procedure:

- Input the source and target molecule IDs defined in Step 1.

- The tool solves a linear programming (LP) optimization problem to maximize the theoretical yield of the target molecule from the source, while rigorously maintaining mass, energy, charge, and atom balance [34].

- Output: A single, carbon- and energy-balanced overall reaction stoichiometry. This reaction defines the net conversion that subsequent pathway designs must achieve.

Step 3: Generate Pathway Designs with novoStoic

- Action: Submit the overall stoichiometry from optStoic to the novoStoic module.

- Parameterization:

- Set the maximum number of reaction steps allowed in a pathway (e.g., 4-6 steps).

- Define the maximum number of pathway variants to be generated (e.g., 10-20 designs) [34].

- Procedure: The algorithm explores both database reactions and novel, hypothetical biochemical transformations to find connecting routes between the source and target [17] [34].

- Output: A list of plausible pathway designs. For hydroxytyrosol, this step successfully identified novel routes that were shorter and required reduced cofactor usage compared to known pathways, potentially reducing metabolic burden and improving production efficiency [17].

Step 4: Evaluate Thermodynamic Feasibility with dGPredictor

- Action: Automatically or manually assess the pathways generated by novoStoic using the dGPredictor tool.

- Procedure:

- For each reaction in a proposed pathway, dGPredictor calculates the standard Gibbs energy change (ΔG'°).

- It uses structure-agnostic chemical moieties to analyze molecules, allowing it to handle novel metabolites not present in standard databases [17] [34].

- Reactions with a significantly positive ΔG'° (thermodynamically unfavorable) are flagged.

- Output: Pathways are filtered and ranked based on thermodynamic feasibility. This safeguards against proposing routes with energetically infeasible steps [17].

Step 5: Select Enzymes for Novel Steps with EnzRank

- Action: For any novel, non-catalogued reaction steps in the thermodynamically feasible pathways, use the EnzRank module.

- Procedure:

- The tool takes the reaction rule and the SMILES string of the novel substrate as input.

- It uses a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to analyze patterns in enzyme amino acid sequences and substrate structures [17] [36].

- It queries the KEGG and Rhea databases via their APIs to fetch relevant enzyme sequences and computes a compatibility score [34].

- Output: A rank-ordered list of the top known enzyme candidates (e.g., the top 5) most likely to be engineered for activity with the novel substrate, each with a probability score [34]. For instance, for a novel hydroxylation step, EnzRank might identify a promiscuous hydroxylase like 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase as a prime candidate for re-engineering [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, both computational and biological, that are essential for utilizing the novoStoic2.0 platform effectively.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for novoStoic2.0

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in Workflow | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| MetaNetX Database | Biochemical Database | Primary source of reactions & molecules for de novo pathway design [17] [34] | Publicly available at https://www.metanetx.org/ |

| KEGG & Rhea Databases | Biochemical Database | Used for thermodynamic profiling (KEGG) and enzyme sequence data (KEGG, Rhea) [34] | KEGG API; Rhea API [34] |

| dGPredictor Moieties | Computational Descriptor | Structure-agnostic chemical groups for ΔG'° estimation of novel molecules [17] [34] | Integrated within the novoStoic2.0 platform |

| EnzRank CNN Model | Machine Learning Model | Rank-orders enzyme sequences for compatibility with novel substrates [17] [34] | Integrated within the novoStoic2.0 platform |

| Custom Enzyme Sequence | Biological Reagent | User-provided sequence for evaluation in standalone EnzRank mode [34] | Manually input via the web interface |

| 2-Chloro-6-methoxypurine riboside | 2-Chloro-6-methoxypurine riboside, MF:C11H13ClN4O5, MW:316.70 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (S,R,S)-AHPC-C10-NHBoc | (S,R,S)-AHPC-C10-NHBoc|VHL Ligand-Linker Conjugate | (S,R,S)-AHPC-C10-NHBoc is an E3 ligase ligand-linker conjugate for BET-targeted PROTAC research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

novoStoic2.0 represents a significant advancement in computational metabolic engineering by integrating multiple critical design tasks into a single, user-friendly platform. Its ability to generate pathways that are not only stoichiometrically efficient but also thermodynamically feasible and linked to engineerable enzyme candidates directly addresses a key bottleneck in the design-build-test cycle. By streamlining the path from concept to experimentally-viable pathway, as demonstrated for molecules like hydroxytyrosol, novoStoic2.0 empowers researchers to more rapidly develop sustainable bioprocesses for a wide array of chemical targets.

The integration of computational tools into metabolic engineering has revolutionized the development of microbial cell factories for producing high-value pharmaceuticals. This case study examines the implementation of these workflows for the biosynthesis of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) and dopamine, tyrosine-derived compounds with significant therapeutic value. L-DOPA remains the gold-standard treatment for Parkinson's disease, while dopamine has applications in treating various neurological and cardiovascular conditions [37] [38]. The complex nature of these compounds and the lack of well-established biosynthetic routes present significant challenges that computational approaches can effectively address [37]. This research is framed within a broader thesis on computational tools for biosynthetic pathway prediction, demonstrating how in silico methods facilitate the discovery and optimization of pathways for pharmaceutical production.

Computational Workflow Design

Integrated Tool Framework

The implemented workflow combines multiple computational tools to create a comprehensive pipeline from pathway design to enzyme selection. This integrated approach leverages the strengths of specialized algorithms at each stage of the design process [37] [39].

Table: Computational Tools for Biosynthetic Pathway Design

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Enumeration | FindPath [37] | Generates potential pathways from starting compounds to targets | Graph-based search algorithms |

| Retrobiosynthesis | BNICE.ch [37] [29], RetroPath2.0 [37] | Deconstructs target molecules to precursors using biochemical rules | Generalized enzymatic reaction rules |

| Pathway Analysis | ShikiAtlas Retrotoolbox [37] | Analyzes and ranks generated pathways | User-friendly interface, links with enzyme selection tools |

| Enzyme Selection | BridgIT [37] [29], Selenzyme [37] | Assigns EC numbers and suggests candidate enzymes | Reaction similarity mapping, sequence-based prediction |

| Gene Discovery | GDEE Pipeline [37] | Rank candidates based on binding affinity | Structure-based molecular docking |

Pathway Generation and Selection Criteria

Pathway generation begins with specifying tyrosine as the starting compound and the target molecule (e.g., L-DOPA or dopamine). Using the ShikiAtlas Retrotoolbox, parameters are set to a maximum of 30 reaction steps and a minimum conserved atom ratio (CAR) of 0.34 to ensure metabolic efficiency [37]. The generated pathways are subsequently ranked based on pathway length and average CAR, favoring routes with minimal enzymatic steps and maximum carbon conservation [37]. For derivative compound production, the expansion process involves applying enzymatic reaction rules to biosynthetic pathway intermediates to create a network of accessible compounds, which are then prioritized based on scientific citations, patent data, and biological feasibility [29].

Implementation Protocols

Protocol: Computational Pathway Design for L-DOPA

Objective: Identify and rank biosynthetic pathways from tyrosine to L-DOPA using retrobiosynthesis tools.

- Input Preparation: Define chemical structures of the starting compound (L-tyrosine) and target product (L-DOPA) in SMILES or InChI format.

- Tool Configuration: Access the ShikiAtlas Retrotoolbox (https://lcsb-databases.epfl.ch/SearchShiki). Set the maximum pathway length to 30 steps and minimum CAR to 0.34 [37].

- Pathway Generation: Execute the retrobiosynthesis algorithm. The tool will enumerate all possible biochemical routes connecting tyrosine to L-DOPA.

- Pathway Analysis: Review generated pathways. Rank them according to length (fewest steps preferred) and average CAR (higher values preferred) [37].

- Reaction Identification: For the top-ranked pathways, list all biochemical transformations required at each step.

- Enzyme Assignment: Use BridgIT and Selenzyme to assign potential Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers to each reaction. These tools will provide initial candidate enzyme sequences for further evaluation [37].

Protocol: Enzyme Candidate Selection and Engineering

Objective: Identify and optimize specific enzymes to catalyze key transformations in the selected pathways.

- Template Identification: For each reaction in the pathway, identify a template enzyme with a known 3D structure that catalyzes a similar transformation [37].

- Sequence Homology Search: Perform a BLASTp search against the Swiss-Prot database to identify candidate sequences with at least 20% identity and 80% coverage to the template [37].

- Structure Modeling: Build 15 homology-based models for each candidate sequence using Modeller [37].

- Molecular Docking: Select the five best models for each candidate and perform molecular docking with AutoDock Vina, using the substrate or a reaction intermediate as the ligand. Apply distance constraints to ensure catalytically relevant orientations [37].

- Candidate Ranking: Rank candidate enzymes based on computed binding affinity, using this as a proxy for catalytic efficiency [37].

- Enzyme Engineering (Optional): For enzyme optimization, employ a computational strategy targeting flexible regions distant from the active site:

- Perform B-factor analysis on available structures to identify rigid and hinge regions [40].

- Screen for stabilizing mutations in the rigid region using Rosetta's Cartesian_ddg, focusing on positions with favorable position-specific substitution matrix (PSSM) scores [40].

- Calculate energy differences (ΔΔG) for mutations, prioritizing those with ΔΔG < -1.0 for dimeric forms of the enzyme when relevant [40].

- Group spatially adjacent mutation hotspots and calculate energies for combinatorial variants. Experimentally test variants with the lowest calculated energies [40].

Protocol: In Vivo Pathway Implementation inE. coli

Objective: Construct engineered E. coli strains for de novo production of L-DOPA and dopamine.

- Strain Engineering:

- Select an appropriate E. coli host strain (e.g., BL21 or K-12 derivatives).