Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Natural Products: Bridging Biology and Chemistry for Sustainable Drug Discovery

This article explores the rapidly evolving field of chemoenzymatic synthesis, a hybrid approach that integrates the precision of enzymatic catalysis with the versatility of synthetic chemistry for the efficient production...

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Natural Products: Bridging Biology and Chemistry for Sustainable Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the rapidly evolving field of chemoenzymatic synthesis, a hybrid approach that integrates the precision of enzymatic catalysis with the versatility of synthetic chemistry for the efficient production of complex natural products. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles from enzyme discovery and engineering to the design of multi-step cascades. The scope extends to practical methodologies for synthesizing pharmaceutically relevant compounds, strategies for overcoming industrial-scale challenges, and a comparative analysis validating the advantages of chemoenzymatic approaches over traditional chemical or purely biological methods. By synthesizing the latest research, this review highlights how chemoenzymatic strategies are streamlining access to bioactive molecules and shaping the future of sustainable manufacturing in the pharmaceutical industry.

The Chemoenzymatic Synthesis Paradigm: Principles and Enzyme Toolkits

Chemoenzymatic synthesis represents a powerful hybrid strategy that integrates the precision of enzymatic catalysis with the versatility of synthetic organic chemistry for the efficient construction of complex molecules [1] [2]. This approach harnesses the unparalleled regio- and stereoselectivity of enzymatic transformations while leveraging the broad reaction scope of contemporary organic synthesis to forge chemical bonds that are challenging to achieve through purely biological means [1] [3]. The paradigm has gained significant traction in recent years for streamlining access to bioactive natural products and pharmaceutical targets, offering substantial improvements in synthesis economy, sustainability, and step-efficiency compared to traditional methods [1] [2].

The fundamental advantage of chemoenzymatic strategies lies in their ability to overcome the inherent limitations of both purely biological and purely chemical approaches. While enzymes offer exquisite selectivity under mild, environmentally benign conditions, they catalyze only a limited subset of organic transformations [1] [3]. Conversely, synthetic organic chemistry provides tremendous reaction diversity but often requires harsh conditions and complex protection/deprotection strategies to achieve similar selectivity profiles [2]. By strategically combining these complementary approaches, chemoenzymatic synthesis enables more direct and efficient routes to valuable molecular targets.

Key Applications in Natural Product Synthesis

Recent demonstrations highlight the transformative potential of chemoenzymatic approaches for synthesizing medicinally relevant natural products. The table below summarizes notable examples, illustrating the strategic integration of chemical and enzymatic steps.

Table 1: Recent Chemoenzymatic Syntheses of Bioactive Natural Products

| Natural Product | Biological Activity | Key Enzymatic Step | Key Chemical Step | Synthetic Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jorunnamycin A & Saframycin A [1] [3] | Potent antitumor activity | Dual Pictet-Spengler cyclization via SfmC enzyme | N-methylation with formaldehyde/2-picoline borane | Shortest synthesis to date (18% & 13% overall yield) |

| Podophyllotoxin [1] [3] | Tubulin depolymerizing activity | Oxidative kinetic resolution via 2-ODD-PH dioxygenase | Oxidative enolate coupling or reductive allylation | Improved overall yields and superior stereocontrol |

| Dihydroartemisinic Acid [1] [3] | Artemisinin precursor (antimalarial) | Cyclization via amorphadiene synthase (ADS) | Riley oxidation & diphosphorylation | "Reversed" approach complementary to biosynthetic route |

| Kainic Acid [1] [3] | Neuropharmacological agent | Oxidative cyclization via DsKabC dioxygenase | Reductive amination of L-glutamic acid | Two-step sequence vs. previous six-step approaches |

| Sorbicillinoids [1] [3] | Antiviral activities | FAD-dependent oxidative dearomatization | Diels-Alder cycloaddition or Weitz-Scheffer epoxidation | Elimination of stoichiometric chiral reagents |

| GDC0575 hydrochloride | GDC0575 hydrochloride, CAS:1657014-42-0, MF:C16H21BrClN5O, MW:414.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| HDAC3-IN-T247 | HDAC3-IN-T247, CAS:1451042-18-4, MF:C21H19N5OS, MW:389.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

These case studies demonstrate how strategic placement of enzymatic transformations within synthetic sequences can dramatically simplify access to complex molecular architectures. The enzymatic steps typically provide challenging stereochemical or regiochemical control, while chemical steps enable structural manipulations beyond the scope of biocatalysis.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Podophyllotoxin via Oxidative Kinetic Resolution

This protocol outlines a gram-scale synthesis of podophyllotoxin featuring a biocatalytic kinetic resolution as the key stereocontrolling step [1] [3].

Materials:

- Racemic hydroxyyatein (rac-25)

- E. coli expressing 2-ODD-PH (αKG-dependent dioxygenase)

- α-Ketoglutarate (αKG), FeSO₄, L-ascorbic acid

- Rhodium catalyst (for chemical step)

- Aldehyde 22 and bromide 23 (chemical precursors)

- Standard organic solvents for extraction and chromatography

Procedure:

Preparation of rac-Hydroxyyatein:

- Perform reductive allylation of aldehyde 22 with bromide 23 to afford homoallylic alcohol 24

- Subject alcohol 24 to Rh-catalyzed 1,4-addition to generate rac-hydroxyyatein (rac-25)

Biocatalytic Kinetic Resolution:

- Prepare reaction buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5) containing 2 mM FeSO₄, 2 mM αKG, and 5 mM L-ascorbic acid

- Suspend E. coli cells expressing 2-ODD-PH in reaction buffer to final OD₆₀₀ of 10

- Add rac-25 (1 g/L final concentration) and incubate at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm for 12 hours

- Monitor reaction progress by HPLC or TLC until approximately 50% conversion

Product Isolation:

- Centrifuge reaction mixture at 8,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove cells

- Extract supernatant with ethyl acetate (3 × 100 mL)

- Dry organic layer over anhydrous Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„ and concentrate under reduced pressure

- Purify desired enantiomer (26) by flash chromatography (39% yield, 95% ee)

- Recover unreacted enantiomer (45% recovery, 66% ee)

Final Chemical Steps:

- Perform oxidation/reduction sequence to invert C7 alcohol stereochemistry

- Purify final podophyllotoxin product by recrystallization

Critical Notes:

- Maintain strict anaerobic conditions during the enzymatic reaction to prevent uncoupled oxidation of αKG

- Optimize cell density and substrate concentration to maximize conversion and enantioselectivity

- The protocol enables access to both enantiomers of the intermediate, enhancing synthetic utility

Protocol 2: Two-Step Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Kainic Acid

This protocol describes a streamlined synthesis of kainic acid using a dioxygenase-mediated cyclization on gram-scale [1] [3].

Materials:

- L-Glutamic acid (17)

- 3-Methylcrotonaldehyde (18)

- E. coli expressing DsKabC (αKG-dependent dioxygenase)

- Sodium cyanoborohydride

- α-Ketoglutarate, FeSO₄, L-ascorbic acid

- Potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0)

Procedure:

Synthesis of Prekainic Acid (16):

- Dissolve L-glutamic acid (10 mmol) in 50 mL 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0)

- Add 3-methylcrotonaldehyde (12 mmol) dropwise with stirring

- Slowly add sodium cyanoborohydride (15 mmol) over 30 minutes

- Stir reaction at room temperature for 12 hours

- Acidify to pH 3.0 with 1M HCl and extract with ethyl acetate

- Dry organic layer and concentrate to obtain crude prekainic acid

DsKabC-Mediated Cyclization:

- Prepare reaction buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0) containing 2 mM FeSO₄, 2 mM αKG, and 5 mM L-ascorbic acid

- Resuspend E. coli cells expressing DsKabC in reaction buffer to final OD₆₀₀ of 15

- Add crude prekainic acid directly to the biotransformation mixture (final concentration 5 g/L)

- Incubate at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm for 24 hours

- Monitor reaction completion by HPLC

Product Isolation:

- Centrifuge reaction mixture at 8,000 × g for 15 minutes

- Acidify supernatant to pH 3.0 and extract with n-butanol (3 × 100 mL)

- Concentrate organic layer under reduced pressure

- Purify kainic acid by recrystallization or preparative HPLC (57% yield from prekainic acid)

Critical Notes:

- The reductive amination step can be performed without purification of intermediates

- Cell density and aeration significantly impact DsKabC activity and productivity

- This two-step sequence represents a significant improvement over previous six-step synthetic approaches

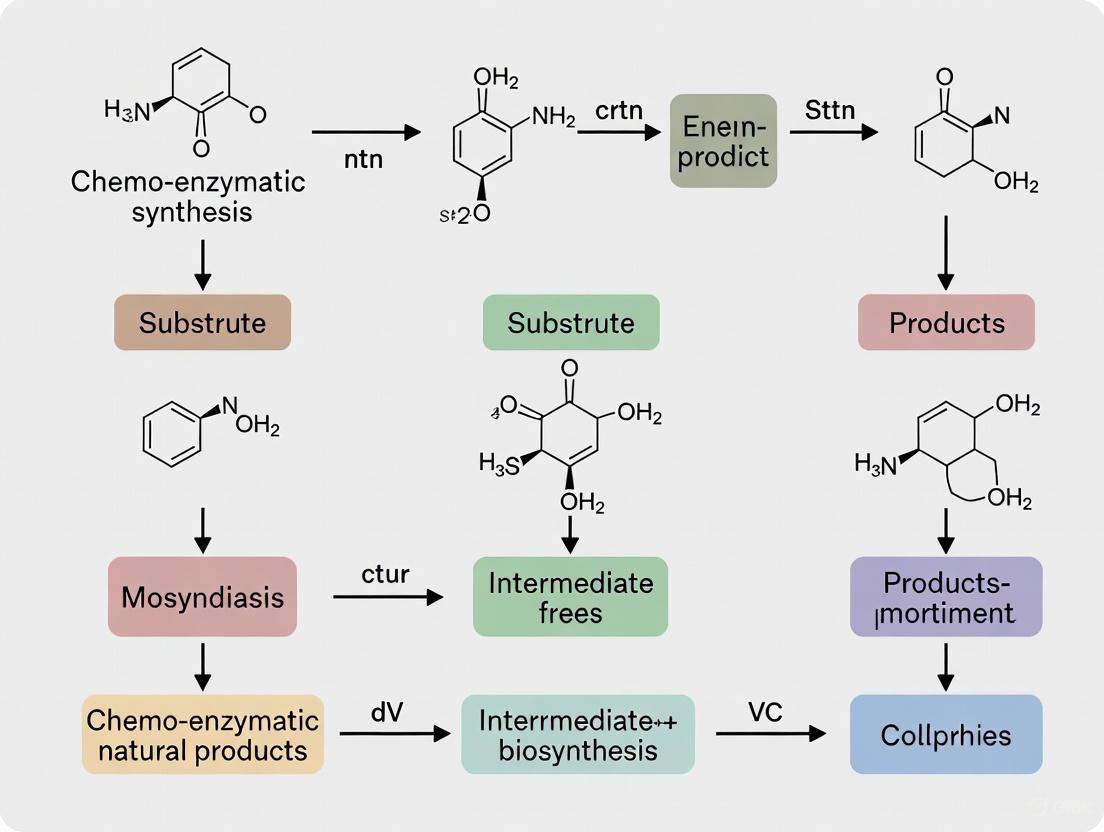

Visualization of Chemoenzymatic Strategies

Workflow for Natural Product Synthesis

The following diagram illustrates the strategic integration of chemical and enzymatic steps in a generalized chemoenzymatic synthesis:

Enzyme Mechanism in Sorbicillinoid Synthesis

The FAD-dependent monooxygenase catalyzed dearomatization mechanism, key to sorbicillinoid synthesis, operates as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of chemoenzymatic synthesis requires specialized reagents and materials. The following table outlines essential components for developing and executing these hybrid strategies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| αKG-Dependent Dioxygenases (DsKabC, 2-ODD-PH) | Oxidative C-C bond formation/cyclization | Kainic acid, podophyllotoxin synthesis | Require αKG, Fe²âº, Oâ‚‚, ascorbate cofactors |

| FAD-Dependent Monooxygenases | Selective oxidative dearomatization | Sorbicillinoid synthesis | NADPH regeneration system often required |

| Pictet-Spenglerases (SfmC) | Dual C-C and C-N bond formation | Tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids | Phosphopantetheinylation often required |

| Terpene Cyclases (Amorphadiene Synthase) | Stereoselective cyclization | Dihydroartemisinic acid synthesis | Requires diphosphate-activated substrates |

| α-Ketoglutarate (αKG) | Cofactor for dioxygenases | Reactions with αKG-dependent enzymes | Stoichiometric consumption requires recycling |

| Acetyl Phosphate (AcP) | ATP regeneration substrate | Kinase cascade reactions | Enables catalytic ATP usage in phosphorylation |

| Immobilized Enzymes | Enhanced stability and reusability | Various biotransformations | Improves operational stability and recovery |

| Engineered Whole Cells | In situ cofactor regeneration | Gram-scale biotransformations | Provides natural cofactor recycling systems |

| JNJ-20788560 | JNJ-20788560, MF:C25H28N2O2, MW:388.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (R)-JNJ-40418677 | (R)-JNJ-40418677, CAS:1146594-87-7, MF:C26H22F6O2, MW:480.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Emerging Applications and Future Perspectives

While natural product synthesis remains a primary application, chemoenzymatic approaches are expanding into new frontiers. Oligonucleotide therapeutics represent an emerging area where chemoenzymatic methods address significant manufacturing challenges [4] [5]. The synthesis of pseudouridine-5'-triphosphate (ΨTP) and its N¹-methylated derivative (m¹ΨTP), critical components of mRNA therapeutics, exemplifies this trend [4]. Recent advances demonstrate integrated approaches combining enzymatic cascade reactions for C-C bond formation with chemical methylation and enzymatic phosphorylation, offering improved efficiency and sustainability over purely chemical routes [4].

Similarly, chemoenzymatic ligation technologies are transforming the production of siRNA and sgRNA, overcoming limitations of conventional solid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis through hybrid approaches that join chemically synthesized fragments using RNA ligases [5]. These methods provide enhanced purity, scalability, and sustainability while reducing manufacturing costs—critical factors for meeting the growing demand for RNA-based therapeutics [5].

The future trajectory of chemoenzymatic synthesis will be shaped by continued advances in enzyme discovery, engineering, and the development of increasingly sophisticated integration strategies. As the field matures, these hybrid approaches are poised to become central methodologies for the efficient synthesis of complex molecules across pharmaceutical and biotechnology applications.

Chemoenzymatic synthesis, which integrates the precision of enzymatic catalysis with the versatility of chemical synthesis, has emerged as a transformative paradigm in the construction of complex molecules, particularly natural products [2] [6] [7]. This approach leverages the inherent strengths of biocatalysts—exquisite stereocontrol, operation under mild aqueous conditions, and a reduced environmental footprint—to address long-standing challenges in traditional synthetic chemistry [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting chemoenzymatic strategies can streamline routes to valuable target compounds, avoid cumbersome protecting group manipulations, and provide more sustainable manufacturing processes [2] [8]. The following application notes detail the core advantages of this methodology, supported by quantitative data and actionable protocols, framed within the context of natural product research.

Application Notes: Quantifying the Advantages

The theoretical benefits of chemoenzymatic synthesis are borne out by empirical performance data across diverse reaction types. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings that highlight its advantages in stereoselectivity, sustainability, and operational efficiency.

Table 1: Superior Stereoselectivity in Biocatalytic Reactions

| Enzyme Class | Reaction Type | Product / Intermediate | Stereoselectivity Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imine Reductase (IRED) | Asymmetric reductive amination | Cinacalcet analog (chiral amine) | >99% enantiomeric excess (ee) | [2] |

| Ketoreductase (KRED) | Carbonyl reduction | Ipatasertib intermediate (alcohol) | 99.7% diastereomeric excess (de) | [2] |

| Lipase B (Candida antarctica) | Kinetic resolution | (S)-Esmolol / (S)-Penbutolol precursors | 97-99% ee | [9] |

| Diterpene Glycosyltransferase | Glycosylation | Steviol glucosides | High regioselectivity; reduced byproducts | [2] |

Table 2: Sustainability and Efficiency Metrics of Chemoenzymatic Processes

| Process Metric | Traditional Chemical Approach | Chemoenzymatic Approach | Advantage | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atom Economy | Often low due to protecting groups & activators | High; simplifies routes, avoids protecting groups | Reduced waste formation | [2] |

| Reaction Conditions | Harsh (high T/p, strong acids/bases) | Mild (ambient T/p, neutral pH) | Lower energy input | [2] |

| Solvent System | Often volatile organic solvents | Can use aqueous or mixed media | Safer, greener profiles | [2] [9] |

| Step Count | Multi-step for introducing chirality | Often shortened via telescoped steps | Higher overall yield | [2] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key chemoenzymatic operations, enabling researchers to implement these techniques in their own laboratories.

Protocol 1: Kinetic Resolution of a Racemic Chlorohydrin Using Immobilized Lipase

This protocol describes the synthesis of a chiral chlorohydrin building block for (S)-esmolol with high enantiopurity, replacing traditional solvents with a greener alternative [9].

- Primary Application: Synthesis of enantiopure β-blockers.

Principle: Lipase B from Candida antarctica selectively acylates one enantiomer of a racemic chlorohydrin, allowing for the separation of the unreacted target enantiomer.

Required Materials and Reagents:

- Racemic chlorohydrin: Methyl 3-(4-(3-chloro-2-hydroxypropoxy)phenyl)propanoate

- Biocatalyst: Immobilized Lipase B from Candida antarctica

- Acyl donor: Vinyl butanoate

- Solvent: Acetonitrile (an alternative to toluene/DCM) [9]

- Equipment: Orbital shaker or controlled-temperature reactor

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Dissolve the racemic chlorohydrin (1.0 equiv) and vinyl butanoate (1.2 equiv) in acetonitrile.

- Biocatalysis: Add immobilized Lipase B (20-30% w/w relative to substrate) to the solution.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at 30-38 °C with constant agitation for 23-48 hours.

- Monitoring: Monitor reaction progress by chiral HPLC or TLC until approximately 50% conversion is achieved.

- Work-up: Filter the reaction mixture to remove the immobilized enzyme.

- Isolation: Concentrate the filtrate under reduced pressure and purify the unreacted (R)-chlorohydrin via flash chromatography.

- Downstream Processing: The isolated (R)-chlorohydrin is subsequently aminated with isopropylamine to yield (S)-esmolol in 97% ee and 26% overall yield over four steps [9].

Protocol 2: Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Terpenoid Natural Product Cores

This protocol outlines a general strategy for constructing complex terpenoid skeletons using a terpene cyclase, as demonstrated in the syntheses of artemisinin and englerin A [6].

- Primary Application: Total synthesis of sesquiterpenes and diterpenes.

Principle: A terpene cyclase enzyme catalyzes the one-step, stereoselective cyclization of a linear isoprenoid diphosphate (e.g., Farnesyl Diphosphate, FPP) into a complex polycyclic core.

Required Materials and Reagents:

- Enzyme: Recombinant terpene cyclase (e.g., Amorpha-4,11-diene synthase for artemisinin).

- Substrate: Farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) or Geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP).

- Cofactors: Mg²⺠or Mn²⺠(for class I cyclases).

- Buffer: Appropriate aqueous buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, pH ~7.5).

- Host System: Engineered S. cerevisiae or E. coli for in vivo fermentation.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- In Vivo Biocatalysis (Fermentation):

- Utilize a metabolically engineered microbial host (e.g., S. cerevisiae) with an upregulated mevalonate pathway to enhance precursor supply.

- Express the gene encoding the desired terpene cyclase in the host.

- Conduct fed-batch fermentation to produce the cyclized terpene (e.g., amorpha-4,11-diene for artemisinin) in multi-gram per liter scale [6].

- Extraction: Extract the terpene core from the fermentation broth using organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate) or overlay systems.

- Chemical Functionalization: The enzymatically derived core is then functionalized using chemical methods. For example:

- Artemisinin: The olefin core is oxidized by a cytochrome P450 enzyme (or chemically) to artemisinic acid, which is then converted to artemisinin via a photooxygenation-driven Schenck ene reaction [6].

- Englerin A: The core guaia-6,10(14)-diene undergoes hydrogen atom transfer isomerization, followed by Sharpless dihydroxylation and epoxidation/cyclization steps to complete the synthesis [6].

- In Vivo Biocatalysis (Fermentation):

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Enzymes for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

| Reagent / Enzyme | Function in Synthesis | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Lipase B (C. antarctica) | Kinetic resolution of racemic alcohols/esters via acylation or hydrolysis. | Production of (S)-Esmolol and (S)-Penbutolol precursors [9]. |

| Ketoreductases (KREDs) | Stereoselective reduction of ketones to secondary alcohols. | Synthesis of chiral alcohol intermediates for APIs like Ipatasertib [2]. |

| Imine Reductases (IREDs) | Asymmetric reductive amination for synthesis of chiral amines. | Preparation of cinacalcet analogs and other amine-containing pharmaceuticals [2]. |

| Terpene Cyclases | Catalyze the cyclization of linear isoprenoid diphosphates into complex polycyclic cores. | One-step construction of artemisinin and englerin A cores [6]. |

| Fe(II)/2OG Dioxygenases | Catalyze oxidative allylic rearrangements and hydroxylations with high selectivity. | Late-stage functionalization in the synthesis of cotylenol and brassicicenes [7]. |

| Vinyl Butanoate | Acyl donor for irreversible transesterification in kinetic resolutions. | Used with lipases to avoid reverse hydrolysis, driving reactions to completion [9]. |

| JP1302 dihydrochloride | JP1302 dihydrochloride, CAS:1259314-65-2, MF:C24H26Cl2N4, MW:441.4 | Chemical Reagent |

| KRN383 analog | KRN383 analog, MF:C17H17N3O4, MW:327.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow of a chemoenzymatic synthesis and a specific signaling pathway engineered in microbial hosts for precursor supply.

Diagram 1: Chemoenzymatic Synthesis Workflow. This flowchart outlines the generalized strategic approach for planning and executing a chemoenzymatic synthesis, from initial target analysis to final product isolation.

Diagram 2: Engineered Mevalonate Pathway for Terpene Synthesis. This diagram shows the key steps of the mevalonate pathway, which is commonly engineered into microbial hosts to provide the universal isoprenoid precursors IPP and DMAPP for the enzymatic production of terpene natural product cores.

The chemo-enzymatic synthesis of natural products represents a frontier in modern organic chemistry and pharmaceutical sciences, merging the precision of chemical synthesis with the selectivity and efficiency of biological catalysts. Within this field, three enzyme classes—Cytochrome P450s (P450s), Transferases, and Dioxygenases—play indispensable roles in constructing and functionalizing complex molecular architectures. This Application Note details the practical application of these enzymes, with a specific focus on P450s, given their predominant role in the catalytic diversification of natural product scaffolds. The content is framed within a broader thesis on advancing chemo-enzymatic strategies, providing researchers with actionable protocols, quantitative data, and visual workflows to facilitate their application in drug development and natural product research.

Cytochrome P450s (P450s): Versatile Biocatalysts

Functional Roles and Strategic Importance

Cytochrome P450s constitute a superfamily of heme-containing monooxygenases that catalyze a diverse array of oxidative reactions, including hydroxylations, epoxidations, and dealkylations. Their significance stems from an unparalleled ability to perform regio- and stereoselective oxidations of unactivated C-H bonds under mild conditions, a transformation notoriously challenging for traditional synthetic chemistry [10] [11].

In the context of natural product synthesis, P450s are pivotal in the structural diversification of core scaffolds. They often act as rate-limiting enzymes or modifying enzymes that introduce structural diversity in the downstream synthesis pathway [11]. For example, in the biosynthesis of plant-derived terpenes, alkaloids, and flavonoids, P450s introduce oxygenated functional groups that are critical for the biological activity of these molecules [11] [12].

Quantitative Catalytic Profile of Key P450s

The table below summarizes the functional attributes of major P450 families involved in the metabolism and synthesis of bioactive compounds, highlighting their broad substrate specificity [10] [11] [13].

Table 1: Key Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Isozymes in Biocatalysis

| P450 Isozyme | Primary Natural Product Role | Reaction Types Catalyzed | Notable Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2 | Xenobiotic metabolism | Oxidation, Demethylation | Caffeine, Nicotine [10] |

| CYP2C9 | Drug metabolism | Hydroxylation | Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) [10] |

| CYP2C19 | Drug metabolism | Hydroxylation, Demethylation | Proton Pump Inhibitors [10] |

| CYP2D6 | Drug metabolism, Prodrug activation | Hydroxylation, O-dealkylation | Codeine (prodrug) to Morphine [10] |

| CYP3A4 | Metabolism of ~50% of drugs | Hydroxylation, N-dealkylation | Statins, Macrolides [10] |

| CYP540A2 | Fatty acid hydroxylation | β-hydroxylation | Medium-Chain Fatty Acids (C7-C12) [14] |

| P450BM-3 (CYP102) | Fatty acid functionalization | ω-1 to ω-3 Hydroxylation | Medium/Long-Chain Fatty Acids [14] |

| Biosynthetic P450s | Natural product diversification | Alkaloid Oxidation, Terpenoid Hydroxylation | Terpenoid, Alkaloid, Flavonoid scaffolds [11] [13] |

Experimental Protocol: P450-Catalyzed Hydroxylation of a Tricyclic Intermediate

This protocol details the chemo-enzymatic synthesis of cotylenol, a fusicoccane diterpenoid, leveraging P450 enzymes for a critical C-H oxidation step. The following workflow visualizes the key stages of this process.

Diagram 1: Chemo-enzymatic synthesis workflow for cotylenol (3).

Materials and Reagents

- Key Intermediate: Tricyclic ketone 20 (synthesized as per the workflow above) [15].

- Enzymes: Heterologously expressed and purified Bsc9 (a non-heme dioxygenase, N-His6-tagged). Note: The partner enzyme BscD was reported insoluble in this system [15].

- Buffers: Suitable assay buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5).

- Cofactors: α-Ketoglutarate (2 mM, as a cosubstrate), Fe(II) (e.g., Ammonium iron(II) sulfate hexahydrate, (NH₄)₂Fe(SO₄)₂·6H₂O) [15].

- Quenching Solution: Ethyl acetate or another organic solvent for extraction.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Reaction Setup: In a suitable vial, prepare a 1 mL reaction mixture containing:

- ~ 0.1 - 0.5 mg of substrate 20 (from a stock solution in DMSO or ethanol, keeping final organic solvent concentration < 2% v/v).

- 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5).

- 2 mM α-ketoglutarate.

- 1 mM (NH₄)₂Fe(SO₄)₂·6H₂O.

- 5 - 20 µM purified Bsc9 enzyme.

- The original study used a related enzyme system (BscD/Bsc9) to convert compound 20 to the C3-oxidized product, a direct precursor to cotylenol [15].

Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at a controlled temperature (e.g., 30°C) with gentle shaking or agitation for 2 - 16 hours.

Reaction Quenching: Terminate the reaction by adding an equal volume of ethyl acetate (1 mL). Vortex vigorously for 1 minute to extract the organic products.

Product Recovery: Centrifuge the mixture at 10,000 x g for 5 minutes to separate phases. Carefully transfer the organic (upper) layer to a new vial.

Analysis: Analyze the organic extract using analytical techniques such as Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) or High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). Compare the retention factors/times against an authentic standard of the expected oxidized product to confirm conversion.

Unique Electron Transfer Systems in P450s

A critical aspect of P450 catalysis is the electron transfer mechanism that fuels the monooxygenase reaction. A recent study identified a unique, self-contained system in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans.

Mechanism of the CBBR-CYP540A2 System

The system involves:

- CYP540A2: A P450 that β-hydroxylates medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs).

- CBBR: A natural fusion protein of Cytochrome b5 (Cyt b5) and Cytochrome b5 reductase (Cyt b5R) [14].

This fusion protein efficiently transfers electrons from NADH to CYP540A2. A predicted linker region between the FAD- and Cyt b5-domains of CBBR is critical for modulating this electron transfer [14]. The following diagram illustrates this unique pathway and its integration into a novel β-oxidation mechanism.

Diagram 2: Unique CBBR electron transfer to P450 and its role in an alternative β-oxidation pathway.

Engineering P450s for Enhanced Performance

The application of wild-type P450s in synthesis often faces challenges such as poor expression, limited substrate scope, and low catalytic efficiency. Protein engineering provides powerful solutions, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Advanced Engineering Strategies for P450 Enzymes

| Engineering Strategy | Primary Objective | Key Methodologies | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heme & Cofactor Engineering | Improve heme supply & incorporation | Host engineering (e.g., ALA synthase overexpression), Heme pathway regulation [13] | Enhanced total P450 expression and functional folding in S. cerevisiae [13]. |

| Redox Partner Engineering | Enhance electron transfer efficiency | Use of natural fusion proteins (e.g., CYP540A2/CBBR system [14]), Construction of artificial fusion proteins [12] [13]. | Increased coupling efficiency and total turnover numbers (TTN). |

| Enzyme & Active Site Engineering | Alter substrate selectivity/ specificity, improve stability | Directed evolution, Site-saturation mutagenesis, Rational design based on structural data [12] [13]. | Production of non-natural terpenoid and alkaloid derivatives in yeast cell factories [12]. |

| Expression & Compartmentalization | Increase local enzyme concentration | Subcellular targeting (e.g., to mitochondria or ER), Membrane engineering, Use of synthetic scaffolds [12]. | Improved supply of P450s and pathway intermediates, boosting final product titer. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for P450-based Chemo-enzymatic Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| CYP540A2 & CBBR System | Hydroxylation of medium-chain fatty acids at the β-position. | From Aspergillus nidulans; CBBR is a natural fusion protein for efficient electron transfer from NADH [14]. |

| Bsc9 (NHD) | Enzymatic C-H oxidation in fusicoccane synthesis. | Catalyzes the installation of the C3 alcohol on the cotylenol tricyclic scaffold [15]. |

| Heterologous Hosts (E. coli, S. cerevisiae) | Recombinant enzyme expression and whole-cell biotransformation. | S. cerevisiae is preferred for eukaryotic P450s due to its internal membrane system and native mevalonate pathway [12]. |

| Cofactors (NADH, α-Ketoglutarate) | Essential electron and energy sources for enzymatic reactions. | NADH for CBBR-dependent systems [14]; α-Ketoglutarate for non-heme dioxygenases like Bsc9 [15]. |

| Multi-kinase inhibitor 1 | N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-4-(6-((4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)benzamide|CID 44129660 | Explore N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-4-(6-((4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)benzamide (CAS 778277-15-9), a Bcr-Abl inhibitor for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| MK-0812 Succinate | MK-0812 Succinate, MF:C28H40F3N3O7, MW:587.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of P450s, alongside transferases and dioxygenases, into chemo-enzymatic synthesis pipelines marks a transformative advancement in natural product research. The detailed protocols, engineering strategies, and mechanistic insights provided in this Application Note offer a practical framework for scientists to leverage these powerful biocatalysts. By adopting these approaches, researchers can overcome traditional synthetic challenges, accelerate the development of high-value compounds, and drive innovation in drug discovery and green biomanufacturing.

The field of biocatalysis is undergoing a transformative shift, moving beyond the use of native enzymes to the strategic engineering of bespoke biocatalysts. This evolution is particularly pivotal for the chemo-enzymatic synthesis of natural products, where engineered enzymes provide unmatched regio- and stereoselectivity that streamlines the construction of complex molecular architectures often inaccessible through purely chemical methods [2]. Engineered enzymes have emerged as environmentally friendly catalysts that operate under mild conditions (ambient temperature, neutral pH, aqueous media), offering superb atom economy with minimal waste generation—a critical advantage in sustainable pharmaceutical development [2].

The integration of artificial intelligence and advanced computational tools has accelerated enzyme engineering, enabling researchers to create biocatalysts with novel functions and enhanced performance characteristics [2] [16]. This technological convergence is expanding the synthetic chemist's toolbox, allowing access to previously challenging chemical space in natural product synthesis and opening new avenues for drug discovery and development.

Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Biocatalysts

Computational and AI-Driven Enzyme Design

Modern enzyme engineering leverages computational power to predict and design improved biocatalysts. Structure-guided rational design utilizes detailed enzyme structural information to identify specific amino acid residues for mutation, enhancing properties such as thermostability, substrate specificity, and catalytic efficiency [2] [17]. For example, computer-assisted structure-based design of the diterpene glycosyltransferase UGT76G1 resulted in a variant with a 9°C increase in apparent melting temperature and a 2.5-fold product yield increase [2].

Machine learning and AI have revolutionized enzyme engineering by dramatically improving the accuracy of protein design. Recent breakthroughs demonstrate AI systems capable of generating artificial enzymes from scratch, with some performing comparably to natural enzymes despite significant sequence divergence [16]. These approaches have shown a 30% reduction in the number of variants tested compared to standard directed evolution methods, significantly accelerating the engineering pipeline [16].

Table 1: Key Enzyme Engineering Strategies and Applications

| Engineering Strategy | Key Features | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Rational Design [17] | Structure-function insights, site-directed mutagenesis | Thermostability enhancement, substrate scope expansion |

| Directed Evolution [17] [18] | Random mutagenesis, high-throughput screening | Activity improvement, novel function development |

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction [2] | Phylogenetic analysis, ancestral sequence prediction | Thermostable enzyme platforms (e.g., L-amino acid oxidases) |

| Computational Design [18] | De novo enzyme design, quantum chemical calculations | Novel catalytic activities, mechanistic studies |

| Unnatural Amino Acid Incorporation [18] | Expanded genetic code, novel functional groups | Alternative catalytic mechanisms, enhanced functionality |

Practical Implementation Workflows

The implementation of enzyme engineering strategies follows logical workflows that integrate computational and experimental approaches. The diagram below illustrates the generalized protocol for structure-guided engineering of enzymes:

Application Notes in Chemo-Enzymatic Synthesis

Case Study: Chemo-Enzymatic Synthesis of Ipatasertib Intermediate

The integration of engineered ketoreductases (KREDs) into synthetic routes for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) demonstrates the power of modern biocatalysis. In the synthesis of ipatasertib, a potent protein kinase B inhibitor, a KRED from Sporidiobolus salmonicolor was engineered through a combination of mutational scanning and structure-guided rational design [2].

Protocol: Ketoreductase Engineering and Application

- Library Generation: Create focused mutant libraries using machine-learning guided approaches to reduce screening burden [2]

- Screening: Implement high-throughput assays to identify variants with improved activity and diastereoselectivity

- Process Optimization: Scale identified variants for gram-scale synthesis (100 g/L ketone loading)

- Reaction Conditions: 30-hour reaction time, achieving ≥98% conversion with 99.7% diastereomeric excess (R,R-trans) [2]

The engineered variant containing ten amino acid substitutions exhibited a 64-fold higher apparent kcat and improved robustness under process conditions compared to the wild-type enzyme [2]. This case exemplifies how enzyme engineering can transform a limiting biocatalytic step into a highly efficient synthetic platform.

Case Study: Imine Reductase Engineering for Chiral Amine Synthesis

Chiral amines represent important structural motifs in pharmaceuticals, yet their asymmetric synthesis remains challenging. Engineering of imine reductases (IREDs) has addressed previous limitations in substrate scope and activity toward bulky amines [2].

Protocol: Increasing-Molecule-Volume Screening for IREDs

- Library Screening: Implement rapid protocol for identifying IREDs with preference for bulky amine substrates

- Scope Evaluation: Test identified IRED-G02 variant against diverse substrate panels (135+ secondary and tertiary amines)

- Process Application: Employ kinetic resolution approach for cinacalcet API analog synthesis

- Performance Metrics: Achieve >99% enantiomeric excess with 48% conversion in gram-scale synthesis [2]

This engineering approach overcame traditional limitations of IREDs, expanding the toolbox for asymmetric amine synthesis in pharmaceutical contexts.

Table 2: Engineered Enzymes in Natural Product Synthesis

| Natural Product | Engineered Enzyme | Key Improvement | Synthetic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jorunnamycin A [1] | SfmC (dual Pictet-Spenglerase) | One-pot formation of pentacyclic core | Shortest synthesis to date (common core + methylation) |

| Podophyllotoxin [1] | 2-ODD-PH (dioxygenase) | Gram-scale biotransformation | 95% yield in key enzymatic step, superior stereocontrol |

| Dihydroartemisinic Acid [1] | Amorphadiene synthase (ADS) | Substrate scope expansion | "Reversed" synthetic approach, 78% yield of cyclized product |

| Sorbicillinoids [1] | FAD-dependent monooxygenase | Enantioselective dearomatization | Eliminates stoichiometric chiral reagents, improves economy |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of engineered enzymes in chemo-enzymatic synthesis requires specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential research reagents for enzyme engineering and application:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Introduction of specific amino acid changes | Critical for rational design approaches; enable precise modifications |

| Unnatural Amino Acids [18] | Incorporation of novel functional groups | Expand catalytic mechanisms (e.g., N δ-methyl histidine for enhanced hydrolysis) |

| Cofactor Regeneration Systems | Maintain cofactor levels during reaction | Essential for oxidative enzymes and ATP-dependent processes |

| Immobilization Supports | Enzyme stabilization and reusability | Enable heterogeneous catalysis, simplify product separation |

| Fluorescent Activity Reporters | High-throughput screening | Facilitate rapid variant identification in directed evolution |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Substrates | Reaction mechanism elucidation | Enable detailed kinetic and structural studies |

| Extremophile Cell Lysates [17] | Source of stable enzyme scaffolds | Provide thermostable and solvent-tolerant enzyme platforms |

| MK-8719 | MK-8719, CAS:1382799-40-7, MF:C9H14F2N2O3S, MW:268.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| m-PEG5-SH | m-PEG5-SH, CAS:524030-00-0, MF:C11H24O5S, MW:268.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Engineering Techniques

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) represents a powerful approach for generating stable enzyme scaffolds. This method predicts ancestral sequences from multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees, often resulting in enzymes with improved thermostability and soluble expression [2]. For example, ASR was used to design a novel L-amino acid oxidase (HTAncLAAO2) with high thermostability and long-term stability [2]. Subsequent structure-guided mutagenesis (W220A variant) yielded a more than 6-fold increase in kcat for L-tryptophan, creating a promising starting point for oxidase engineering [2].

Reaction Scope Expansion Through Mechanism Diversion

Advanced engineering strategies focus on diverting natural enzymatic mechanisms toward non-native transformations. The diagram below illustrates how mechanistic understanding enables reaction diversification:

Protocol: Enolate Interception in Ene-Reductases

- Active Site Engineering: Mutate conserved tyrosine to phenylalanine in flavin-dependent ene-reductases (EREDs) to prevent natural protonation

- Enolate Trapping: Utilize the persistent enolate for SN2-type reactions with pendant halides

- Product Formation: Generate chiral cyclopropanes with good yields and selectivities [18]

- Scope Expansion: Apply similar strategy to access diverse carbocyclization reactions

This approach exemplifies how deep mechanistic understanding enables the repurposing of natural enzymatic machinery for synthetic applications beyond native biological functions.

Engineered enzyme discovery represents a paradigm shift in chemo-enzymatic synthesis, moving biocatalysis from a supplemental tool to a central strategy in natural product synthesis. The integration of computational design, directed evolution, and mechanistic diversification has created an powerful platform for solving synthetic challenges in pharmaceutical development.

As enzyme engineering methodologies continue to advance, particularly with the integration of AI and machine learning, the scope of accessible natural products and complex pharmaceuticals will expand dramatically. These developments promise to shorten synthetic routes, improve sustainability, and provide access to chemical space that remains challenging for traditional synthetic approaches. The systematic application of engineered biocatalysts will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in the future of natural product research and drug development.

The Role of Enzyme Promiscuity in Expanding Synthetic Possibilities

Enzyme promiscuity, defined as the ability of an enzyme to catalyze secondary reactions beyond its native physiological function, has emerged as a transformative concept in synthetic chemistry [19]. This phenomenon allows enzymes to process non-native substrates (substrate promiscuity), catalyze chemically distinct transformations (catalytic promiscuity), or function under non-physiological conditions (condition promiscuity) [20] [21]. In the context of natural product synthesis, this inherent flexibility provides synthetic chemists with powerful tools to access complex molecular architectures through innovative retrosynthetic disconnections that would be challenging using traditional chemical methods alone [22].

The physiological irrelevance of promiscuous activities—either due to low catalytic efficiency or absence of substrates in native environments—belies their immense synthetic utility [23]. Evolution has shaped enzyme active sites to be "good enough" for their primary biological roles, leaving behind a treasure trove of latent catalytic capabilities that can be harnessed for synthetic purposes [23]. This accidental versatility now serves as the foundation for developing novel biocatalytic strategies that combine the precision of enzymatic catalysis with the flexibility of traditional synthetic chemistry [24] [22].

Mechanisms and Classification of Enzyme Promiscuity

Fundamental Mechanisms

The structural and mechanistic basis of enzyme promiscuity can be categorized into three primary modes that enable non-native catalytic activities:

Active Site Plasticity: Many enzymes possess flexible active sites that can accommodate promiscuous substrates through conformational adjustments [19]. For example, β-lactamase and sulfo-transferase display increased plasticity that enables altered substrate hydrolysis profiles [19]. This flexibility allows the enzyme-substrate complex to adopt diverse conformations that facilitate both native and promiscuous functions, sometimes through different residue networks within the same active site groove [19].

Ambiguous Substrate Recognition: Promiscuous enzymes can often bind multiple structurally distinct substrates through different interaction modes within the same active site [19]. Cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP) exemplify this mechanism, with CYP3A4 showing remarkable promiscuity in substrate specificity and cooperative substrate binding despite sharing a common protein fold [19].

Cofactor Ambiguity: Many metalloenzymes can utilize different metal cofactors, leading to altered catalytic activities and product profiles [19]. The enzyme NDM-1 from Klebsiella pneumoniae demonstrates extreme cofactor promiscuity, capable of hydrolyzing nearly all known β-lactam-based antibiotics using different metal cofactors and reaction mechanisms [19].

Quantitative Assessment of Promiscuity

Researchers have developed quantitative indices to measure and compare enzyme promiscuity levels. The promiscuity index (J-value) defines a scale from 0 (perfect specificity for one substrate) to 1 (no preference for any substrate) [25]. Drug-metabolizing enzymes typically exhibit J-values > 0.7, while their substrate-specific homologs generally range between 0.3 and 0.6 [25].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Promiscuous Enzyme Activities

| Enzyme | Native Reaction | Promiscuous Reaction | Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imine reductase (IRED-G02) | Reduction of native imines | Reduction of bulky amine substrates | Significant conversion for >135 amines | [24] |

| Ketoreductase from Sporidiobolus salmonicolor | Native ketone reduction | Reduction of ipatasertib precursor | 64-fold higher apparent kcat vs wild-type | [24] |

| α-Oxoamine synthase (ThAOS) | Native C-C bond formation | Expanded substrate range with simplified thioesters | Activity with N-acetylcysteamine substrates | [24] |

| Verruculogen synthase (FtmOx1) | Fumitremorgin B endoperoxidation | 13-epi-fumitremorgin B peroxidation | 9% yield of 13-epi-verruculogen | [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Harnessing Enzyme Promiscuity

Protocol 1: Substrate Promiscuity Profiling

Objective: Systematic evaluation of enzyme substrate scope beyond native substrates.

Materials:

- Purified enzyme (e.g., imine reductase, ketoreductase, or α-oxoamine synthase)

- Library of structurally diverse substrate analogs

- Cofactors and buffers specific to enzyme class

- Analytical instrumentation (HPLC, GC-MS, NMR)

Procedure:

- Enzyme Preparation: Express and purify the target enzyme using standard recombinant techniques. For membrane-associated enzymes (e.g., CYPs), prepare appropriate membrane fractions or nanodisc reconstitutions.

- Reaction Setup: In a 96-well plate format, add 90 μL of assay buffer containing necessary cofactors (e.g., NADPH for reductases, α-ketoglutarate for dioxygenases).

- Substrate Addition: Add 10 μL of substrate solution (from a diverse chemical library) to each well, using a range of concentrations (typically 0.1-10 mM).

- Reaction Initiation: Add 10 μL of enzyme solution to each well, including appropriate negative controls (no enzyme, no substrate).

- Incubation: Incubate plates at optimal temperature with shaking for 2-24 hours.

- Reaction Quenching: Add 100 μL of quenching solution (e.g., acetonitrile for HPLC analysis) to stop reactions.

- Product Analysis: Analyze reaction mixtures using appropriate analytical methods. For IRED screening, employ chiral HPLC to determine enantioselectivity.

- Data Analysis: Calculate conversion rates, enantiomeric excess (where applicable), and kinetic parameters (KM, kcat) for promising substrates.

Applications: This protocol enables identification of novel substrate classes for known enzymes, as demonstrated by Zhang et al. who identified three imine reductases with preference for bulky amine substrates, leading to synthesis of over 135 secondary and tertiary amines [24].

Protocol 2: Chemo-enzymatic Natural Product Synthesis

Objective: Integration of promiscuous enzymatic steps into synthetic routes for natural products.

Materials:

- Enzyme expression system (e.g., E. coli BL21(DE3) with pET vector)

- Substrate analogs for enzymatic transformation

- Traditional synthetic chemistry reagents and catalysts

- Purification materials (flash chromatography, HPLC)

- Analytical standards

Procedure:

- Retrosynthetic Analysis: Identify strategic bond disconnections where enzymatic promiscuity can simplify synthesis. Focus on challenging stereocenters or reactive functionalities.

- Enzyme Selection: Based on the transformation required, select candidate enzymes with reported promiscuous activities for related chemistries.

- Enzyme Production: Express and purify enzymes as in Protocol 1. Consider co-expression of multiple enzymes for cascade reactions.

- Substrate Synthesis: Chemically synthesize the proposed enzyme substrate, ensuring compatibility with enzyme active site requirements.

- Biocatalytic Reaction Optimization:

- Screen reaction conditions (pH, temperature, co-solvents) for promiscuous activity

- Determine optimal enzyme loading (typically 1-10 mol%)

- Identify necessary cofactors and additives

- Scale-up: Perform preparative-scale biotransformation with monitoring of reaction progress.

- Product Isolation: Purify the enzymatic product using standard chromatographic techniques.

- Chemical Elaboration: Employ traditional synthetic methods to further elaborate the enzymatically-derived intermediate.

- Structural Validation: Confirm product structure and stereochemistry using spectroscopic methods (NMR, MS, X-ray crystallography).

Applications: This approach was successfully employed in the synthesis of 13-oxoverruculogen, where FtmOx1 accepted 13-epi-fumitremorgin B as a non-native substrate for endoperoxidation, enabling a 10-step synthesis of this complex alkaloid [26].

Figure 1: Workflow for chemo-enzymatic natural product synthesis exploiting enzyme promiscuity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Exploring Enzyme Promiscuity

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promiscuous Enzymes | Imine reductases (IREDs), Ketoreductases (KRs), P450 monooxygenases, α-Oxoamine synthases (AOSs) | Catalyze non-native transformations in synthetic routes | Protein engineering often required to enhance promiscuous activities [24] |

| Cofactor Systems | NAD(P)H regeneration systems, α-Ketoglutarate, ATP regeneration | Drive enzymatic reactions requiring stoichiometric cofactors | Essential for maintaining catalyst productivity in preparative synthesis |

| Engineered Host Strains | E. coli BL21(DE3), P. pastoris | Heterologous enzyme production with high yield | Codon optimization and fusion tags improve expression of challenging enzymes |

| Analytical Tools | Chiral HPLC columns, GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR | Reaction monitoring, enantioselectivity determination, structural elucidation | Rapid analytics enable high-throughput screening of promiscuous activities |

| Specialized Substrates | N-acetylcysteamine (SNAc) thioesters, Bulky amine substrates, Non-native terpenoids | Probe substrate scope limits of promiscuous enzymes | Simplify synthetic routes while maintaining high stereoselectivity [24] |

| Tocrifluor 1117 | Tocrifluor 1117, CAS:1186195-59-4, MF:C56H53Cl2N7O5, MW:975.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| TC-2559 difumarate | TC-2559 difumarate, MF:C20H26N2O9, MW:438.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Applications in Natural Product Synthesis

Case Study: Verruculogen Synthesis via FtmOx1 Promiscuity

The synthesis of 13-oxoverruculogen exemplifies the strategic application of enzyme promiscuity in natural product synthesis [26]. Verruculogen synthase (FtmOx1), a non-heme iron and α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase, natively catalyzes the endoperoxidation of fumitremorgin B to form verruculogen. Researchers exploited the promiscuity of FtmOx1 by demonstrating that it could accept 13-epi-fumitremorgin B as a non-native substrate, producing 13-epi-verruculogen in 9% yield [26].

Experimental Details:

- Enzyme Preparation: FtmOx1 was heterologously expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) with an N-terminal His6-tag and purified under aerobic conditions using Ni-NTA resin [26].

- Reaction Conditions: The enzymatic transformation used 10 mol% FtmOx1, α-ketoglutarate (1 mM), and L-ascorbate (2 mM) in buffer at room temperature [26].

- Strategic Advantage: This biocatalytic approach enabled direct installation of the challenging eight-membered endoperoxide ring, obviating the need for multi-step manipulation of sensitive peroxide functionality required in previous total syntheses [26].

Multi-Enzyme Cascades and Systems Biocatalysis

Advanced applications of enzyme promiscuity now extend to multi-enzymatic cascades, chemoenzymatic cascades, and photo-biocatalytic cascades that combine multiple catalytic steps in one-pot systems [24]. These approaches significantly enhance synthetic efficiency by eliminating intermediate isolation and purification steps while minimizing waste generation.

Notable Examples:

- Merck's Molnupiravir Synthesis: A chemo-enzymatic cascade combining lipase-catalyzed 5'-acylation of ribose with a five-enzyme cascade for 1-phosphorylation and nucleobase installation [22].

- Isoquinoline Alkaloid Synthesis: Hailes group employed promiscuous Pictet-Spenglerases in convergent synthesis of isoquinoline scaffolds, followed by regioselective enzymatic methylation to obtain protoberberine alkaloids [22].

- Enzyme-Catalyzed Multicomponent Reactions (MCRs): Recent advances demonstrate the combination of enzyme promiscuity with multicomponent reactions for constructing diverse heterocyclic scaffolds including pyridines, pyrimidines, pyrazoles, and quinolones under mild conditions [27].

Figure 2: Strategic framework for exploiting enzyme promiscuity in natural product synthesis

Engineering and Optimization Strategies

Protein Engineering for Enhanced Promiscuity

Deliberate engineering of enzyme active sites can significantly enhance promiscuous activities for synthetic applications. Several strategic approaches have proven successful:

Structure-Guided Rational Design: As demonstrated by Malca et al., combining mutational scanning with structure-guided design generated a ketoreductase variant with 64-fold higher apparent kcat and improved robustness for synthesis of the ipatasertib precursor [24].

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR): This phylogenetic approach predicts and resurrects ancestral enzyme sequences, which often display enhanced promiscuity and stability compared to modern counterparts [24]. For example, ancestral L-amino acid oxidase (HTAncLAAO2) exhibited high thermostability and could be further optimized through structure-guided mutagenesis [24].

Computational Design: Go et al. employed Rosetta-based protein design to engineer the diterpene glycosyltransferase UGT76G1, resulting in a 9°C increase in apparent Tm and 2.5-fold higher product yield while reducing byproduct formation [24].

Reaction Engineering Solutions

Engineering the reaction environment complements protein engineering strategies for optimizing promiscuous activities:

Media Engineering: Systematic optimization of reaction conditions including co-solvents, pH, and temperature can dramatically enhance promiscuous reaction rates [20]. Organic solvents particularly enable reversals of hydrolytic equilibrium, expanding synthetic utility.

Immobilization Techniques: Enzyme immobilization on solid supports improves stability and recyclability while potentially altering selectivity patterns through surface interactions.

Cofactor Engineering: Regeneration systems for expensive cofactors (NAD(P)H, ATP) enable practical synthetic applications of cofactor-dependent promiscuous enzymes.

The strategic integration of these engineering approaches with fundamental understanding of promiscuity mechanisms provides a powerful framework for developing novel biocatalytic transformations that expand the synthetic chemist's toolbox for natural product synthesis and diversification.

Strategic Implementations and Industrial Case Studies in Drug Synthesis

The push for more sustainable and efficient synthetic methodologies in natural product and pharmaceutical research has catalyzed the growth of chemoenzymatic cascade reactions. These processes combine the precision and mild reaction conditions of biocatalysis with the broad reactivity of synthetic chemistry, creating powerful synthetic tools [28]. This approach is inspired by biosynthetic pathways in living organisms, where enzymes orchestrate complex multi-step transformations in a highly efficient and compartmentalized manner [29] [30]. The integration of multiple steps into one-pot systems minimizes waste, improves atom economy, and reduces the need for intermediate purification, contributing to more environmentally friendly synthesis [29] [28]. For researchers in natural product synthesis, this strategy is particularly valuable for constructing complex molecular architectures, such as terpenoid skeletons, which can be further functionalized using radical chemistry or other synthetic methods [6]. Despite the advantages, designing these cascades requires careful consideration of catalyst compatibility, as enzymes and chemical catalysts often operate optimally under different conditions [28]. This application note details practical protocols and strategies for implementing such cascades, focusing on the production of valuable fragrance aldehydes and other natural product scaffolds.

Strategic Approaches and Key Protocols

Two Novel Cascades for Fragrance Aldehydes

Recent research demonstrates the power of chemo-enzymatic cascades for converting renewable phenylpropenes into high-value fragrance and flavor aldehydes, such as vanillin and piperonal [29]. Two distinct strategic pathways have been developed, each comprising multiple steps performed in a one-pot or sequential one-pot manner.

Route A: Isomerization-Cleavage Cascade This two-step cascade involves an initial chemical isomerization followed by an enzymatic alkene cleavage [29].

- Step 1 - Pd-Catalyzed Isomerization: A solvent-free palladium(II) chloride (PdClâ‚‚)-catalyzed isomerization converts the allylic double bond of the phenylpropene starting material into a vinylic double bond, forming the intermediate (E)-isomer with high selectivity and quantitative conversion for most substrates [29].

- Step 2 - Enzymatic Cleavage: The isomerized reaction mixture is diluted with ethanol and subjected to cleavage using an aromatic dioxygenase (ADO). This enzyme cleaves the alkene bond to deliver the desired aldehyde without requiring a cofactor, simplifying the reaction setup [29].

Route B: Oxidation-BVMO-Esterase-ADH Cascade This four-step cascade combines a copper-free Wacker oxidation with a three-step enzymatic sequence [29].

- Step 1 - Copper-Free Wacker Oxidation: The phenylpropene starting material is oxidized to the corresponding ketone.

- Step 2 - Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenation: The ketone is oxidized to an ester using a phenylacetone monooxygenase (PAMO) from Thermobifida fusca.

- Step 3 - Esterase Hydrolysis: The ester is hydrolyzed to the primary alcohol using an esterase from Pseudomonas fluorescens (PfeI).

- Step 4 - Alcohol Oxidation: The primary alcohol is finally oxidized to the target aldehyde by an alcohol dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas putida (AlkJ) [29].

Protocol: One-Pot Synthesis of Aldehydes via Route A (Isomerization-Cleavage)

Objective: To synthesize aromatic aldehydes from renewable phenylpropenes (e.g., eugenol, estragole) using a two-step chemo-enzymatic cascade.

Materials:

- Substrates: Phenylpropene starting material (e.g., 1a–8a from [29]).

- Chemical Catalyst: Palladium(II) chloride (PdClâ‚‚).

- Biocatalyst: Aromatic dioxygenase (ADO).

- Solvent: Absolute Ethanol (EtOH).

Procedure:

- Pd-Catalyzed Isomerization: In a reaction vessel, combine the phenylpropene substrate (100 mg, 0.48–0.8 mmol) and PdCl₂ (2.5–5.0 mol%). Perform the reaction under neat (solvent-free) conditions at room temperature or 40°C for 24 hours with stirring. Monitor the reaction by TLC or GC-MS until complete conversion to the (E)-isomer is achieved [29].

- Reaction Mixture Dilution: Without purifying the isomerization mixture, dilute it with absolute ethanol to a concentration of 0.5 M relative to the original substrate [29].

- Enzymatic Cleavage: Add the aromatic dioxygenase (ADO) to the diluted reaction mixture. Incubate the reaction at the enzyme's optimal temperature and pH with appropriate mixing. Monitor the reaction for the formation of the aldehyde product.

- Work-up and Purification: After the reaction is complete, separate the catalyst(s) by centrifugation or filtration. Concentrate the supernatant under reduced pressure and purify the desired aldehyde product using standard techniques like flash chromatography or distillation.

Notes: The PdClâ‚‚ catalyst can be isolated and reused for subsequent isomerization reactions. Ensure the enzyme is handled according to specific storage and activity requirements [29].

Protocol: Multi-Step Synthesis of Aldehydes via Route B (Oxidation Cascade)

Objective: To produce aromatic aldehydes via a four-step sequence involving a chemical oxidation followed by three enzymatic steps.

Materials:

- Substrates: Phenylpropene starting material.

- Chemical Reagents: Reagents for copper-free Wacker oxidation.

- Biocatalysts: Phenylacetone monooxygenase from Thermobifida fusca (PAMO), Esterase from Pseudomonas fluorescens (PfeI), Alcohol dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas putida (AlkJ).

- Cofactors: Required cofactors for the monooxygenase and dehydrogenase (e.g., NADPH). A cofactor regeneration system is recommended for economic viability.

Procedure:

- Wacker Oxidation: Perform the copper-free Wacker oxidation on the phenylpropene substrate according to the published protocol to obtain the ketone intermediate [29].

- Baeyer-Villiger Oxidation: To the ketone-containing mixture, add the PAMO enzyme and necessary cofactors. Incubate under optimal conditions to convert the ketone to the corresponding ester.

- Ester Hydrolysis: Introduce the esterase (PfeI) to the reaction mixture to hydrolyze the ester to the primary alcohol.

- Alcohol Oxidation: Finally, add the alcohol dehydrogenase (AlkJ) and its required cofactors to oxidize the primary alcohol to the target aldehyde.

- Work-up and Purification: Quench the reaction and isolate the aldehyde product using standard extraction and purification techniques.

Notes: This sequence can be performed as a one-pot cascade if the conditions are compatible, or as a sequential one-pot where components are added at different stages. The yield and efficiency depend heavily on balancing the activities of all catalysts and managing potential incompatibilities [29] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents and their functions in chemoenzymatic cascades.

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function in Chemoenzymatic Cascades | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Candida antarctica Lipase B (CAL-B) | Regioselective acylation of glycerol backbone in lipid synthesis [31]. | High regioselectivity for primary alcohols; immobilized form available for reusability. |

| Palladium(II) Chloride (PdClâ‚‚) | Chemical catalyst for isomerization of allylic double bonds [29]. | Effective under solvent-free (neat) conditions; can be recovered and reused. |

| Aromatic Dioxygenase (ADO) | Cofactor-independent cleavage of alkenes to aldehydes [29]. | Broad substrate promiscuity; operates without metabolic redox equivalents. |

| p-Methoxybenzyl (PMB) Ether | Protective group for alcohols in multi-step synthesis [31]. | Stable to various conditions; can be removed under mild oxidative conditions (e.g., DDQ). |

| Phenylacetone Monooxygenase (PAMO) | Enzymatic Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of ketones to esters [29]. | Useful for inserting an oxygen atom, expanding functional group compatibility. |

| UNC1079 | 1,4-Phenylenebis(1,4'-bipiperidin-1'-ylmethanone) | Explore the research applications of 1,4-Phenylenebis(1,4'-bipiperidin-1'-ylmethanone). This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| VU6001376 | VU6001376, MF:C18H14F2N6OS, MW:400.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quantitative Performance of Chemoenzymatic Cascades

Table 2: Summary of quantitative data from reported chemoenzymatic cascades.

| Cascade Description | Starting Material | Target Product | Yield | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Step Cascade (Route A) | Eugenol (7a) | Vanillin | Quantitative (Isomerization) | Solvent-free, cofactor-independent enzyme | [29] |

| Four-Step Cascade (Route B) | Various Phenylpropenes (1a–8a) | Aldehydes | Up to 55% (over 4 steps) | Combines metal and multi-enzyme catalysis | [29] |

| Chemoenzymatic Synthesis | Artemisinic Acid (2) | Artemisinin (1) | Process-scale | Combines microbial fermentation and chemical radical steps | [6] |

Workflow and Data Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and decision-making process involved in designing a chemoenzymatic cascade, integrating the strategies discussed in the protocols.

Diagram 1: Strategic workflow for designing chemoenzymatic cascades based on renewable starting materials.

The protocols and strategies outlined herein provide a robust framework for the design and execution of chemoenzymatic cascades. The integration of chemical and enzymatic catalysis, as demonstrated by the efficient synthesis of fragrance aldehydes and complex natural product scaffolds, represents a significant advancement in sustainable synthesis. Success in this field hinges on the thoughtful selection and combination of catalysts, careful management of reaction conditions to ensure compatibility, and the application of innovative solutions like protective group chemistry. As the palette of available biocatalysts expands through protein engineering and the incorporation of unnatural components, the scope and efficiency of these cascades will continue to grow, solidifying their role in the future of green chemistry and natural product research [32].

The chemoenzymatic synthesis of complex natural products represents a frontier in sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing. This approach leverages the exquisite selectivity of biological catalysts to perform transformations that are challenging for traditional synthetic chemistry, often under mild and environmentally benign conditions [24]. Within this field, monoterpenoid indole alkaloids (MIAs) like the teleocidins are highly valued for their unique pharmacological activities, particularly their ability to activate protein kinase C (PKC) [33]. However, their structural complexity, characterized by a distinctive nine-membered indolactam V core, makes their chemical synthesis inefficient, typically relying on heavy metals and resulting in low yields [33] [34].

This application note details a recent breakthrough: the development of an efficient, scalable chemoenzymatic route to produce teleocidin B compounds and their derivatives. The strategy centers on the engineering of a critical cytochrome P450 enzyme system to overcome key catalytic bottlenecks, enabling the gram-scale production of these pharmaceutically promising compounds [33].

Background and Significance

Teleocidins as Valuable Natural Products

Teleocidins are terpene indole compounds isolated from Streptomyces bacteria. Their robust bioactivity as PKC activators has drawn keen interest from natural product researchers and pharmacologists [34]. While PKC activators were historically regarded as tumor growth enhancers, recent studies suggest that subtype-specific PKC activation can actually repress tumor growth, renewing the impetus to create libraries of teleocidin analogs for drug discovery [34] [33]. The indolactam V structure is known to be most critical for this PKC activation [34].

The Biosynthetic Challenge

The traditional total chemical synthesis of teleocidins is hampered by:

- Low overall yields [33].

- Dependence on heavy metal catalysts [33].

- Challenges in achieving the correct stereochemistry of the complex core.

Biosynthetic approaches in native microbial producers, while promising, face issues of low enzymatic efficiency and poor scalability [33]. The key biosynthetic step involves the formation of a C–N bond between N-13 and C-4 to create the indolactam V structure, a reaction catalyzed by the P450 enzyme TleB [34]. The inherent limitations of native P450s, such as low catalytic efficiency and dependence on specific redox partners, have been a major bottleneck for industrial application [35].

Engineered P450 System for Indolactam V Production

Protein Engineering of TleB

The central challenge was to enhance the activity of the P450 enzyme TleB, which catalyzes the radical-mediated C–N bond formation to create the indolactam V core from the linear dipeptide N-methyl-L-valyl-L-tryptophanol (NMVT) [34] [33].

Engineering Strategy: To overcome the natural inefficiency of the two-component P450 system, a self-sufficient fusion enzyme was created. The researchers engineered TleB by fusing it with its cognate reductase module. This design mimics natural self-sufficient P450 systems, like that of Bacillus megaterium P450BM3 (CYP102A1), which are known for significantly increased electron transport efficiency [35].

Outcome: This protein engineering effort resulted in a dramatic boost in productivity, increasing the titre of indolactam V to 868.8 mg Lâ»Â¹ [33]. The fusion enzyme streamlines electron transfer from NAD(P)H to the heme center, enhancing the catalytic turnover and overcoming a major bottleneck in the pathway.

Quantitative Data on Production Yields

The table below summarizes the production achievements enabled by the engineered P450 system and subsequent process optimization.

Table 1: Production Yields of Teleocidin Intermediates and Final Products

| Compound | Engineered System / Approach | Production Yield | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indolactam V | TleB P450 fused with reductase module | 868.8 mg Lâ»Â¹ | Lab-scale fermentation |

| Teleocidin B Isomers | Dual-cell factory with engineered hMAT2A-TleD, TleB, TleC | 714.7 mg Lâ»Â¹ (total yield) | Lab-scale fermentation |

| Indolactam V | Scalable fermentation in recombinant E. coli | 430 mg | Gram-scale |

| Teleocidin A1 | Scalable fermentation in recombinant E. coli | 170 mg | Gram-scale |

| Teleocidin B Isomers | Scalable fermentation in recombinant E. coli | 300 mg | Gram-scale |

Source: Adapted from [33]

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Engineering and Expression of the Self-Sufficient TleB Fusion Enzyme

Objective: To create and produce a fusion enzyme of TleB and its reductase domain for high-efficiency indolactam V synthesis.

Materials:

- Genes encoding TleB and its reductase partner.

- Plasmid vector (e.g., pET series for E. coli expression).

- E. coli BL21(DE3) or similar expression strain.

- LB or TB media with appropriate antibiotics.

- Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG).

- Lysis buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol).

- Ni-NTA affinity resin for purification (if using a His-tag construct).

Method:

- Gene Fusion: Fuse the gene of the TleB P450 domain to the 3' end of the gene for its native ferredoxin reductase partner using a flexible peptide linker (e.g., GGGGS repeat).

- Cloning: Ligate the fusion gene into an expression plasmid and transform into the expression host.

- Expression: Inoculate a culture and grow at 37°C until OD₆₀₀ reaches ~0.6-0.8. Induce protein expression with 0.1-0.5 mM IPTG. Reduce temperature to 16-18°C and incubate with shaking for 16-20 hours.

- Purification: Harvest cells by centrifugation. Resuspend pellet in lysis buffer and lyse by sonication. Clarify the lysate by centrifugation. Purify the fusion protein using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC).

- Activity Assay: Confirm enzyme activity by incubating the purified fusion protein with 1 mM NMVT and 2 mM NADPH in a suitable reaction buffer (e.g., 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) at 30°C. Monitor the formation of indolactam V via LC-MS or HPLC.

Protocol 2: Gram-Scale Fermentation for Indolactam V Production

Objective: To produce indolactam V at gram-scale using the engineered E. coli strain expressing the self-sufficient TleB.

Materials:

- Engineered E. coli strain harboring the TleB-reductase fusion.

- Terrific Broth (TB) media with antibiotics.

- Fermenter (e.g., 5 L bioreactor).

- Feed solution (50% w/v glucose).

- IPTG for induction.

Method:

- Seed Culture: Inoculate a single colony into a flask containing TB medium with antibiotic. Grow overnight at 30°C, 200 rpm.

- Bioreactor Inoculation: Transfer the seed culture to the bioreactor containing sterile TB medium to an initial OD₆₀₀ of 0.1.

- Fermentation Parameters: Maintain temperature at 30°C, dissolved oxygen (DO) at 30-40% (via airflow, agitation, and pure oxygen if necessary), and pH at 7.0 (using ammonium hydroxide or sulfuric acid).

- Induction and Feeding: When the culture reaches the late exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ~20), induce protein expression with 0.1 mM IPTG. Simultaneously, initiate a fed-batch process with a continuous or pulsed feed of 50% glucose solution to maintain metabolic activity.

- Harvest and Extraction: After 48-72 hours post-induction, harvest the cells by centrifugation. Extract indolactam V from the cell pellet or the culture broth using a suitable solvent like ethyl acetate. Concentrate the extract under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Purify indolactam V using normal-phase or reversed-phase flash chromatography. Validate the product's identity and purity by NMR and HPLC.

Visualization of the Chemoenzymatic Strategy

The following diagram illustrates the overall metabolic engineering and synthetic biology strategy used to reconstruct the teleocidin biosynthetic pathway in a microbial host.

Diagram 1: Engineered teleocidin biosynthesis pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section lists the key enzymes, reagents, and systems that were critical to the success of this chemoenzymatic synthesis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Teleocidin Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Protocol | Key Feature / Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| TleB-Reductase Fusion Enzyme | Catalyzes the radical-mediated C-N bond formation to create the indolactam V core. | Self-sufficient P450 system; eliminates need for external redox partners, boosting efficiency [33] [35]. |

| Engineered hMAT2A-TleD | A engineered fusion methyltransferase that catalyzes C-methylation, triggering terpene ring cyclization. | Fusion construct enhances activity; key for forming the final teleocidin B scaffold [33]. |

| TleC (Prenyltransferase) | Transfers a prenyl group to the indolactam V intermediate. | Utilizes a rare "reverse prenylation" mechanism with C-3 tertiary carbocation [34]. |

| Dual-Cell Factory System | A co-culture system where different strains express complementary parts of the pathway. | Allows for spatial separation of incompatible enzymatic steps; optimizes overall pathway flux [33]. |

| Recombinant E. coli System | The heterologous host for expressing the teleocidin biosynthetic pathway. | Scalable, well-characterized chassis for high-density fermentation and gram-scale production [33]. |

| NADPH Regeneration System | Provides reducing equivalents (electrons) required for P450 catalysis. | Can be supported internally by host metabolism or via external feeding to sustain high turnover [35] [36]. |

| WWamide-3 | WWamide-3, CAS:149636-89-5, MF:C46H66N12O9S, MW:963.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| FIDAS-5 | FIDAS-5, MF:C15H13ClFN, MW:261.72 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This case study demonstrates that protein engineering of P450 systems is a powerful strategy for overcoming inherent catalytic limitations and achieving industrially relevant synthesis of complex natural products. The creation of a self-sufficient TleB enzyme, combined with a sophisticated dual-cell factory approach, enabled the scalable production of teleocidin derivatives that were previously inaccessible in practical quantities [33]. This work provides a robust and sustainable platform for supplying these bioactive compounds for further pharmacological evaluation and sets a compelling precedent for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of other high-value MIAs. The principles applied here—including enzyme fusion for self-sufficiency, machine-learning aided engineering, and system-level pathway optimization—are widely applicable to other challenging targets in natural product-based drug development [24] [35].