Analytical Techniques for Biosynthetic Product Validation: From Discovery to Clinical Application

This comprehensive review addresses the critical role of analytical techniques in validating natural product biosynthesis for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Analytical Techniques for Biosynthetic Product Validation: From Discovery to Clinical Application

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical role of analytical techniques in validating natural product biosynthesis for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It systematically explores the foundational principles of biosynthetic gene clusters and silent pathway activation, details established and emerging methodological approaches for structural elucidation, provides troubleshooting frameworks for common optimization challenges, and establishes validation criteria through comparative analysis and regulatory standards. By integrating genomics, metabolomics, and synthetic biology with rigorous analytical validation, this article provides a complete roadmap for confirming biosynthetic product identity, purity, and biological relevance from initial discovery through regulatory approval.

Foundations of Biosynthetic Validation: Unlocking Nature's Chemical Diversity

Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) represent coordinated groups of genes that encode the molecular machinery for synthesizing specialized metabolites, which include many of our most crucial antibiotics, anticancer drugs, and immunosuppressants. The identification and analysis of these genomic blueprints have revolutionized natural product discovery, shifting the paradigm from traditional bioactivity-guided isolation to targeted genome mining. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the computational tools for BGC identification is paramount for unlocking the vast chemical potential encoded within microbial and plant genomes. These in silico approaches have revealed that only a fraction of BGCs—estimated at just 3%—have been experimentally characterized, leaving an immense reservoir of untapped chemical diversity awaiting discovery [1].

The field has evolved significantly from early reference-based alignment methods to sophisticated machine learning and deep learning algorithms that can detect novel BGC classes beyond known templates. This comparison guide provides an objective assessment of the leading computational strategies for BGC identification, their underlying methodologies, performance characteristics, and practical applications in biosynthetic product validation research. By comparing the experimental data and technical capabilities of these approaches, this guide serves as a strategic resource for scientists selecting appropriate tools for their specific research contexts in natural product discovery and engineering.

Computational Tools for BGC Identification: A Comparative Analysis

Tool Classifications and Core Algorithms

BGC identification tools primarily fall into three algorithmic categories: rule-based systems that use manually curated knowledge to identify BGCs based on known domain architectures and gene arrangements; hidden Markov model (HMM)-based tools that employ probabilistic models to detect BGCs based on sequence homology to known biosynthetic domains; and machine/deep learning approaches that utilize neural networks and other pattern recognition algorithms to identify BGCs based on training datasets of known and putative clusters.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major BGC Identification Tools

| Tool | Algorithm Type | Input Data | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH [2] [3] | Rule-based + HMM | Genomic DNA | Identifies known BGC classes, compares to MIBiG database, predicts cluster boundaries | Comprehensive, user-friendly web interface, extensive documentation | Primarily detects BGCs similar to known clusters, limited novel class discovery |

| DeepBGC [4] | Deep Learning (BiLSTM RNN) | Pfam domain sequences | Uses pfam2vec embeddings, RNNs detect long-range dependencies, random forest classification | Reduced false positives, identifies novel BGC classes, improved accuracy | Requires substantial training data, computational intensity |

| ClusterFinder [4] | HMM | Pfam domain sequences | Pathway-centric HMM approach, detects biosynthetic domains | Established method, integrates with antiSMASH | Limited long-range dependency detection, higher false positive rate |

| Regulatory Network-Based [1] | Regulatory inference + Co-expression | Genomic DNA + Transcriptomic data | Identifies TF binding sites, correlates with BGC expression, functional prediction | Predicts BGC function, identifies regulatory triggers, discovers non-canonical clusters | Requires multiple data types, computationally complex |

Performance Metrics and Detection Capabilities

Independent validation studies have demonstrated significant performance differences between BGC identification tools. DeepBGC shows a notable improvement in reducing false positive rates compared to HMM-based tools like ClusterFinder, while maintaining high sensitivity for known BGC classes [4]. In direct comparisons using reference genomes with fully annotated BGCs, DeepBGC achieved higher accuracy in BGC detection from genome sequences, particularly for identifying BGCs of novel classes that lack close homologs in reference databases [4].

The functional annotation capabilities also vary considerably between tools. While antiSMASH excels at identifying BGCs with high similarity to characterized clusters in the MIBiG database, regulatory-based approaches can associate BGCs with specific physiological functions through their connection to transcription factor networks. For example, linking BGCs to the iron-dependent regulator DmdR1 successfully identified novel operons involved in siderophore biosynthesis [1].

Experimental Protocols for BGC Identification and Analysis

Standard antiSMASH Workflow for BGC Detection

The antiSMASH (Antibiotics and Secondary Metabolite Analysis SHell) pipeline represents one of the most widely used methodologies for comprehensive BGC identification in bacterial genomes [2] [3]. The following protocol outlines the key experimental steps:

Genome Preparation and Quality Assessment: Obtain high-quality genomic DNA sequences, preferably assembled to chromosome level, though high-quality contig-level assemblies are acceptable. For the 199 marine bacterial genomes analyzed in a recent study, complete genomes were used when available [2].

BGC Prediction with antiSMASH 7.0: Process genomes through antiSMASH 7.0 bacterial version using default detection settings. Enable complementary analysis modules including KnownClusterBlast, ClusterBlast, SubClusterBlast, and Pfam domain annotation to maximize detection capabilities [2].

Results Compilation and Classification: Systematically compile antiSMASH results into a structured database, recording the total number of BGCs and their classifications for each genome. Categorize BGCs into types such as non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), polyketide synthases (PKS), betalactone, NI-siderophores, and ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs) [2].

Comparative Analysis: Compare BGC abundance and diversity across target genomes to identify strain-specific and conserved biosynthetic capabilities. In the marine bacteria study, this revealed 29 distinct BGC types across the 199 genomes [2].

Phylogenetic Contextualization: Perform phylogenetic analysis using appropriate marker genes (e.g., rpoB) to evolutionary relationships. Map BGC distributions onto the phylogenetic tree to identify horizontal transfer events and lineage-specific conservation [2].

Advanced DeepBGC Methodology for Novel BGC Detection

For researchers targeting novel BGC classes that may be missed by rule-based approaches, DeepBGC offers a sophisticated deep learning alternative with the following protocol [4]:

Open Reading Frame Identification: Predict open reading frames in bacterial genomes using Prodigal (version 2.6.3) with default parameters to identify all potential protein-coding sequences [4].

Protein Family Domain Annotation: Identify protein family domains using HMMER (hmmscan version 3.1b2) against the Pfam database (version 31). Filter hmmscan tabular output to preserve only highest-scoring Pfam regions with e-value <0.01 using the BioPython SearchIO module [4].

Domain Sequence Embedding: Convert the sorted list of Pfam domains into vector representations using the pfam2vec embedding, which applies a word2vec-like skip-gram neural network to generate 100-dimensional domain vectors trained on 3376 bacterial genomes [4].

Bidirectional LSTM Processing: Process the sequence of Pfam domain vectors through a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) Recurrent Neural Network with 128 units and dropout of 0.2. This architecture enables the detection of both short- and long-range dependency effects between adjacent and distant genomic entities [4].

BGC Score Prediction and Classification: Generate prediction scores between 0 and 1 representing the probability of each domain being part of a BGC using a time-distributed dense layer with sigmoid activation. Apply post-processing filters to merge BGC regions at most one gene apart and filter out regions with less than 2000 nucleotides or regions lacking known biosynthetic domains [4].

Regulatory Network-Based BGC Functional Prediction

An innovative approach that combines regulatory network analysis with BGC identification enables functional prediction of cryptic clusters [1]:

Transcription Factor Binding Site Prediction: Use precalculated and manually curated position weight matrices (PWMs) from databases like LogoMotif for genome-wide prediction of transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs). Classify matches as low, medium, or high confidence based on prediction scores and information content [1].

Gene Regulatory Network Construction: Build a comprehensive gene regulatory network mapping genome-wide regulation of BGCs based on TFBS predictions. Identify both direct and indirect regulatory interactions between regulators and BGCs [1].

Co-expression Analysis Integration: Supplement regulatory predictions with global gene expression patterns from transcriptomic data to identify co-expressed gene networks. This helps refine BGC boundaries and identify functionally related genes outside canonical cluster boundaries [1].

Functional Association Mapping: Associate unknown BGCs with specific physiological functions based on their shared regulatory context with characterized BGCs. For example, BGCs controlled by the iron-responsive regulator DmdR1 are likely involved in siderophore production [1].

Experimental Validation: Prioritize candidate BGCs for experimental validation through gene inactivation and metabolic profiling. In Streptomyces coelicolor, this approach identified the novel operon desJGH essential for desferrioxamine B biosynthesis [1].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BGC Analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Annotation | Prodigal [4] | Open reading frame prediction | Identifies protein-coding genes in genomic sequences |

| Protein Domain Database | Pfam [4] | Protein family classification | Provides domain annotations for biosynthetic enzymes |

| BGC Reference Database | MIBiG [2] | Known BGC repository | Reference for comparing newly identified BGCs against characterized clusters |

| Sequence Analysis | HMMER [4] | Hidden Markov Model search | Identifies domain homology in protein sequences |

| BGC Network Analysis | BiG-SCAPE [2] | Gene Cluster Family analysis | Groups BGCs into families based on sequence similarity |

| Phylogenetic Analysis | MEGA11 [2] | Evolutionary genetics analysis | Constructs phylogenetic trees for evolutionary context |

| Network Visualization | Cytoscape [2] | Biological network visualization | Visualizes BGC similarity networks and regulatory interactions |

BGC Diversity and Distribution: Insights from Genomic Studies

Large-scale genomic surveys have revealed remarkable diversity in BGC distribution across bacterial taxa. Analysis of 199 marine bacterial genomes identified 29 distinct BGC types, with non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), betalactone, and NI-siderophores being most predominant [2]. This comprehensive study demonstrated how BGC distribution often follows phylogenetic lines, with certain BGC families showing clade-specific distribution patterns [2].

In the Actinomycetota, renowned for their biosynthetic potential, comparative genomic analysis of 98 Brevibacterium strains revealed that only 2.5% of gene clusters constitute the core genome, while the majority occur as singletons or cloud genes present in fewer than ten strains [3]. This pattern highlights the extensive specialized metabolism that has evolved in these bacteria, with specific BGC types like siderophore clusters and carotenoid-related BGCs showing distinct phylogenetic distributions [3].

Table 3: BGC Diversity Across Bacterial Taxa from Genomic Studies

| Study Organism | Sample Size | Total BGCs Identified | Predominant BGC Types | Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Bacteria [2] | 199 genomes | 1,379 BGCs | NRPS, betalactone, NI-siderophores | Vibrioferrin BGCs showed high genetic variability in accessory genes while core biosynthetic genes remained conserved |

| Brevibacterium [3] | 98 genomes | Not specified | Phenazine-related, PKS, RiPPs | Only 2.5% of gene clusters in core genome; most BGCs occur as singletons or cloud genes |

| Amycolatopsis [5] | 43 genomes | Not specified | NRP, Polyketide, Saccharide | Confirmed extraordinary richness of silent BGCs; identified 11 characterized BGCs in MIBiG repository |

| Planctomycetota [6] | 256 genomes | Not specified | PKS, NRPS, RiPPs | Revealed wide divergent nature of BGCs; evidence of horizontal gene transfer in BGC distribution |

Advanced Integrative Approaches and Future Directions

The integration of multi-omics data represents the cutting edge of BGC discovery and functional characterization. Combining genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic datasets enables more accurate prediction of BGC function and activation conditions [7]. For plant natural products, advanced omics strategies incorporating single-cell sequencing, MS imaging, and machine learning have shown significant potential for elucidating complex biosynthetic pathways [8].

Machine and deep learning approaches continue to evolve, with tools like DeepBGC demonstrating improved capability to identify novel BGC classes beyond the detection limits of rule-based algorithms [4]. The application of natural language processing (NLP) strategies to protein domain sequences has opened new avenues for detecting subtle patterns in BGC organization that escape conventional homology-based approaches [4].

Regulatory-guided genome mining presents another promising frontier, using transcription factor binding site predictions and co-expression networks to associate BGCs with specific physiological functions and environmental triggers [1]. This approach is particularly valuable for prioritizing BGCs for experimental characterization based on predicted ecological roles or biological activities.

As the field advances, the integration of these computational approaches with synthetic biology and heterologous expression platforms will continue to accelerate the discovery and engineering of novel bioactive compounds from diverse biological sources [9] [10].

Bacterial genome sequencing has revealed an immense, untapped reservoir of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) with the potential to produce novel therapeutic molecules. However, the majority of these BGCs are "cryptic" or "silent," meaning they are not expressed under standard laboratory conditions. This silent majority represents a significant opportunity for drug discovery, prompting the development of innovative strategies to activate these hidden pathways. This guide objectively compares the performance of three leading approaches—small molecule elicitors, computational pathway prediction, and genetic manipulation—framed within the context of analytical techniques essential for biosynthetic product validation.

Comparative Analysis of Activation Strategies

The table below provides a performance comparison of the primary strategies used to activate cryptic biosynthetic pathways.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Cryptic Pathway Activation Strategies

| Strategy | Key Mechanism | Reported Success Rate | Key Performance Metrics | Primary Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Elicitors [11] | Use of sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics (e.g., Trimethoprim) to globally induce secondary metabolism. | Served as a global activator of at least five biosynthetic pathways in Burkholderia thailandensis [11]. | High-throughput screening compatible; Can simultaneously activate multiple silent clusters. | High-throughput screening compatible; Can simultaneously activate multiple silent clusters. | Requires a pre-established genetic reporter system; Elicitor effect can be strain-specific. |

| Computational Pathway Prediction (BioNavi-NP) [12] | Deep learning-driven, rule-free prediction of biosynthetic pathways from simple building blocks. | Identified pathways for 90.2% of 368 test compounds; Recovered reported building blocks for 72.8% [12]. | Top-10 single-step prediction accuracy of 60.6% (1.7x more accurate than rule-based models) [12]. | Does not require prior knowledge of cluster regulation; Navigates complex multi-step pathways efficiently. | Predictions require experimental validation; Performance depends on training data quality and diversity. |

| Genetic Manipulation (AdpA Overexpression) [13] | Overexpression of a global transcriptional regulator to bind degenerate operator sequences and upregulate silent BGCs. | Elicited production of the antifungal lucensomycin in Streptomyces cyanogenus S136; Activated melanin production and antibacterial activity [13]. | Can activate BGCs lacking cluster-situated regulators; Broad applicability across Streptomyces species. | Can activate BGCs lacking cluster-situated regulators; Broad applicability across Streptomyces species. | Potential for pleiotropic effects, complicating metabolite profiling; Requires genetic tractability of the host. |

Experimental Protocols for Strategy Validation

Robust experimental validation is crucial after selecting an activation strategy. The following protocols detail key methodologies.

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening of Small Molecule Elicitors

This protocol is adapted from a study that used a genetic reporter construct to screen for inducers of silent gene clusters [11].

- Reporter Strain Construction: Clone the promoter region of the target silent BGC upstream of a readily measurable reporter gene (e.g., GFP, lacZ) in the host bacterium.

- Library Screening: Culture the reporter strain in a 96-well or 384-well format, exposing each well to a different compound from a small molecule library. Sub-inhibitory concentrations of clinical antibiotics have been successfully employed as a starting point [11].

- Activity Assessment: Quantify reporter signal (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence) after a defined incubation period. Wells showing a significant signal increase over controls indicate potential elicitor activity.

- Metabolite Validation: Re-treat the wild-type strain (without the reporter) with hit compounds and use Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) to confirm the production of the target metabolite or novel compounds.

Protocol 2: Validating Computationally Predicted Pathways

This protocol outlines how to test the biosynthetic routes proposed by tools like BioNavi-NP [12].

- Pathway Prediction: Input the structure of the target natural product into the BioNavi-NP platform to receive one or more predicted biosynthetic pathways from fundamental building blocks.

- In Vitro Reconstitution: Clone and heterologously express the genes encoding for each enzyme in the proposed pathway. Purify the enzymes and incubate them in sequence with the predicted starting substrates.

- Intermediate Analysis: At each proposed enzymatic step, use analytical techniques like LC-MS or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) to detect and structurally characterize the predicted intermediate compounds.

- Heterologous Production: Assemble the entire set of predicted genes in a suitable microbial host (e.g., E. coli or S. cerevisiae). Cultivate the engineered host and analyze the culture extract for the production of the final target natural product.

This protocol is based on the activation of the silent lucensomycin pathway by manipulating the global regulator adpA [13].

- Strain Engineering: Introduce a plasmid carrying a heterologous adpA gene (or its DNA-binding domain) under a strong, constitutive promoter into the production strain. A landomycin-nonproducing mutant (ΔlanI7) was used to eliminate precursor competition [13].

- Phenotypic Screening: Plate the engineered strain on various solid media (e.g., TSA, ISP5, YMPG) and screen for changes in pigmentation or the emergence of antibiotic activity against bacterial or fungal indicators [13].

- Metabolite Profiling: Grow the strain in liquid media that supports the highest level of activity. Extract metabolites from the culture broth and biomass using solvents like ethyl acetate.

- Compound Identification: Analyze extracts using HPLC-ESI-mass spectrometry. Compare the mass peaks ([M+H]+) and fragmentation patterns to databases to identify known compounds (e.g., lucensomycin at m/z 708.35) or novel metabolites [13].

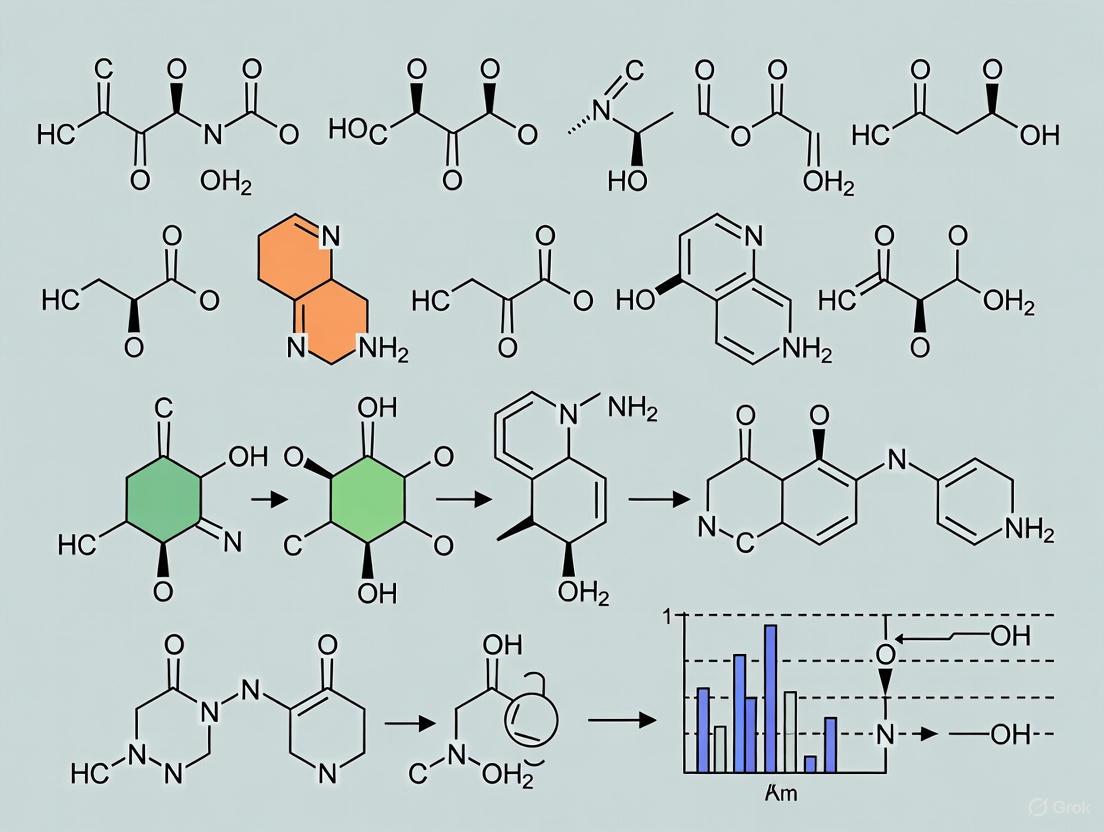

Visualizing Strategic Workflows

The following diagrams, created using the specified color palette, illustrate the logical workflows for the compared strategies.

Small Molecule Elicitor Screening

Computational Pathway Prediction & Validation

Genetic Activation via Global Regulators

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful activation and validation require specific reagents and tools, as detailed below.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pathway Activation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter Plasmids | Enable the construction of reporter strains for high-throughput screening of elicitors by linking promoter activity to a measurable signal. | Plasmids with GFP or lacZ reporter genes; Must be compatible with the host bacterium (e.g., actinobacterial or proteobacterial shuttle vectors). |

| Small Molecule Libraries | Collections of diverse compounds used as potential elicitors to probe the regulatory networks controlling silent BGCs. | Libraries of FDA-approved drugs or natural products; Sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics like trimethoprim are effective starting points [11]. |

| Computational Tools | Software and platforms that predict biosynthetic pathways and enzymes, guiding experimental efforts. | BioNavi-NP for bio-retrosynthesis [12]; Selenzyme or E-zyme for enzyme prediction [12]; Databases like MIBiG, UniProt [14]. |

| Expression Vectors | Plasmids used for heterologous gene expression, crucial for pathway validation and production. | Vectors for inducible expression in common hosts like E. coli (e.g., pET systems) or Streptomyces (e.g., pGM series) [13]. |

| Analytical Standards | Authentic chemical compounds used as references for validating the identity and structure of newly discovered metabolites. | Commercially available natural products; Critical for confirming hits via LC-MS retention time and fragmentation pattern matching. |

| Culture Media Components | Provide the nutritional basis for cultivating diverse microbial strains and can influence the expression of secondary metabolites. | Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), ISP5, YMPG; Medium optimization is often essential for detecting activated compounds [13]. |

| 1-Phenylpent-3-en-1-one | 1-Phenylpent-3-en-1-one, CAS:73481-93-3, MF:C11H12O, MW:160.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,7-Octadiene-3,6-diol | 1,7-Octadiene-3,6-diol, CAS:70475-66-0, MF:C8H14O2, MW:142.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The activation of cryptic biosynthetic pathways is a multi-faceted challenge requiring a suite of complementary strategies. Small molecule elicitors offer a high-throughput, chemical means to probe regulatory biology, while computational tools like BioNavi-NP provide a powerful, knowledge-driven approach to pathway elucidation. Conversely, genetic manipulation via global regulators can bypass complex regulation to directly activate transcription. The choice of strategy depends on the specific research goals, the genetic tractability of the organism, and the available resources. Ultimately, leveraging these strategies in tandem, supported by robust analytical validation, is key to unlocking the vast potential of the bacterial "silent majority" for drug discovery and development.

The comprehensive understanding of human health and diseases requires interpreting molecular complexity and variations across multiple levels, including the genome, epigenome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome [15]. Multi-omics data integration combines these individual omic datasets in a sequential or simultaneous manner to understand the interplay of molecules and bridge the gap from genotype to phenotype [15]. This holistic approach has revolutionized medicine and biology by creating avenues for integrated system-level analyses that improve prognostic and predictive accuracy for disease phenotypes, ultimately aiding in better treatment and prevention strategies [15].

In biosynthetic pathway discovery, multi-omics approaches have become indispensable. Plants produce a vast array of specialized metabolites with crucial ecological and physiological roles, but their biosynthetic pathways remain largely elusive [16]. The intricate genetic makeup and functional diversity of these pathways present formidable challenges that single-omics approaches cannot adequately address. Multi-omics integration provides a powerful solution by offering a comprehensive perspective on the entire biosynthetic process, enabling researchers to connect genes to molecules systematically [16] [17].

Multi-Omics Integration Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

Statistical, Deep Learning, and Mechanistic Approaches

Multiple computational methods have been developed for multi-omics integration, each with distinct strengths and applications. These approaches can be broadly categorized into statistical, deep learning, and mechanistic models, with performance varying significantly based on the biological question and data types.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Multi-Omics Integration Methods

| Method | Approach Type | Key Features | Optimal Use Cases | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA+ [18] | Statistical-based (Unsupervised) | Uses latent factors to capture variation across omics; Provides low-dimensional interpretation | Breast cancer subtype classification; Feature selection | F1 score: 0.75; Identified 121 relevant pathways |

| MOGCN [18] | Deep Learning-based | Graph Convolutional Networks with autoencoders for dimensionality reduction | Pattern recognition in complex datasets | F1 score: <0.75; Identified 100 relevant pathways |

| MINIE [19] | Mechanistic (Dynamical modeling) | Bayesian regression with timescale separation modeling; Differential-algebraic equations | Time-series multi-omic network inference; Causal relationship identification | Accurate predictive performance across omic layers; Top performer in single-cell network inference |

| MEANtools [17] | Reaction-rules based | Leverages reaction rules and metabolic structures; Mutual rank-based correlation | Plant biosynthetic pathway prediction; Untargeted discovery | Correctly anticipated 5/7 steps in falcarindiol pathway |

Method Selection Guidelines

The choice of integration method depends heavily on the research objectives, data modalities, and biological questions. Statistical approaches like MOFA+ excel in feature selection and biological interpretability, making them ideal for exploratory analysis and subtype classification [18]. Deep learning methods such as MOGCN offer powerful pattern recognition capabilities but may sacrifice some interpretability [18]. For dynamic processes involving different temporal scales, mechanistic models like MINIE that explicitly account for timescale separation between molecular layers provide superior insights into causal relationships [19]. In plant biosynthetic pathway discovery, reaction-rules based approaches like MEANtools enable untargeted, unsupervised prediction of metabolic pathways by connecting correlated transcripts and metabolites through biochemical transformations [17].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Multi-Omic Network Inference from Time-Series Data

The MINIE pipeline exemplifies a rigorous approach for inferring regulatory networks from time-series multi-omics data [19]. This method is particularly valuable for capturing the temporal dynamics of biological systems, where different molecular layers operate on vastly different timescales.

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection: Acquire time-series data for transcriptomics (preferably single-cell RNA-seq) and metabolomics (bulk measurements)

- Timescale Separation Modeling: Implement differential-algebraic equations (DAEs) to account for faster metabolic dynamics compared to transcriptional changes

- Transcriptome-Metabolome Mapping: Infer initial connections using sparse regression constrained by prior knowledge of metabolic reactions

- Bayesian Regression: Refine network topology using a Bayesian framework that integrates both data modalities

- Validation: Validate inferred networks using both simulated datasets and experimental data from model systems

Key Technical Considerations:

- Metabolic pool turnover in mammalian cells is approximately one minute, while mRNA pool half-life is around ten hours [19]

- Algebraic equations arise from quasi-steady-state approximation due to assumption that metabolic changes occur much faster than transcriptional changes

- The method handles the high-dimensionality and limited sample sizes typical of biological studies through sparse regression techniques [19]

Untargeted Biosynthetic Pathway Discovery

MEANtools provides a systematic workflow for predicting candidate metabolic pathways de novo without prior knowledge of specific compounds or enzymes [17]. This approach is particularly valuable for exploring the extensive "dark matter" of plant specialized metabolism.

Experimental Protocol:

- Multi-omics Data Generation: Collect paired transcriptomic and metabolomic data across multiple conditions, tissues, and timepoints

- Data Preprocessing: Format and annotate input data using standard metabolomic processing pipelines

- Correlation Analysis: Calculate mutual rank-based correlations between mass features and transcript expression

- Reaction Rule Application: Leverage RetroRules database to assess if chemical differences between metabolites can be explained by transcript-associated enzyme families

- Structure Annotation: Match mass features to LOTUS natural products database, accounting for possible adducts

- Pathway Prediction: Generate hypotheses about potential pathways by connecting correlated transcripts and metabolites through biochemical transformations

Key Technical Considerations:

- The mutual rank-based correlation method maximizes highly correlated metabolite-transcript associations while reducing false positives

- Reaction rules are linked to transcript-encoded enzyme families through PFAM-EC mapping

- The approach assesses whether identified reactions can connect transcript-correlated mass features within candidate metabolic pathways [17]

Publicly available data repositories provide essential resources for multi-omics research, offering comprehensive datasets that facilitate integrative analyses.

Table 2: Key Multi-Omics Data Repositories for Biosynthetic Research

| Repository | Data Types | Primary Focus | Sample Size | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [15] | RNA-Seq, DNA-Seq, miRNA-Seq, SNV, CNV, DNA methylation, RPPA | Pan-cancer atlas | >20,000 tumor samples | https://cancergenome.nih.gov/ |

| International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC) [15] | Whole genome sequencing, genomic variations | Cancer genomics | 20,383 donors | https://icgc.org/ |

| Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) [15] | Gene expression, copy number, sequencing | Cancer cell lines | 947 human cell lines | https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ccle |

| Omics Discovery Index (OmicsDI) [15] | Genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics | Consolidated data from 11 repositories | Unified framework | https://www.omicsdi.org/ |

These repositories serve as invaluable resources for method validation, comparative analysis, and hypothesis generation. For example, TCGA data has been used to validate multi-omics integration methods for breast cancer subtype classification, demonstrating the utility of these publicly available resources [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful multi-omics integration requires specialized reagents and computational resources that enable comprehensive molecular profiling and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Integration

| Reagent/Resource | Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometers [20] [16] | Analytical Instrument | Detects and quantifies metabolites with high precision | Metabolite identification; Pathway discovery |

| Next-Generation Sequencers [16] | Genomics Tool | Generates transcriptomic and genomic data | Gene expression profiling; Variant detection |

| LOTUS Database [17] | Computational Resource | Comprehensive well-annotated resource of Natural Products | Metabolite structure annotation |

| RetroRules Database [17] | Biochemical Database | Retrosynthesis-oriented database of enzymatic reactions | Predicting biochemical transformations |

| plantiSMASH [16] | Bioinformatics Tool | Identifies biosynthetic gene clusters in plants | Biosynthetic pathway mining |

| Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) [20] | Analytical Platform | Community curation of mass spectrometry data | Metabolite annotation; Molecular networking |

| Sulfuric acid;tridecan-2-ol | Sulfuric acid;tridecan-2-ol, CAS:65624-93-3, MF:C26H58O6S, MW:498.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 4-Benzylideneoxolan-2-one | 4-Benzylideneoxolan-2-one|High-Quality Research Chemical | 4-Benzylideneoxolan-2-one for Research Use Only. Explore its applications in organic synthesis and medicinal chemistry. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Conceptual Framework for Multi-Omics Integration

The integration of multiple omics layers creates a powerful framework for connecting genes to molecules. This process involves systematically linking information across biological scales to reconstruct functional relationships.

This conceptual framework illustrates how multi-omics integration bridges biological scales, connecting genetic information to observable traits through intermediate molecular layers. The integration process enables researchers to move beyond correlations to establish causal relationships between genes and metabolites [19] [17].

Multi-omics integration approaches represent a paradigm shift in biological research, enabling comprehensive understanding of complex biosynthetic pathways and disease mechanisms. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that method selection should be guided by specific research questions, with statistical approaches like MOFA+ excelling in feature selection for classification tasks, dynamic models like MINIE providing insights into temporal regulation, and reaction-based methods like MEANtools enabling de novo pathway discovery [19] [18] [17].

As the field advances, several trends are shaping its future. The incorporation of artificial intelligence and deep learning continues to enhance pattern recognition in complex datasets [20] [18]. The development of single-molecule imaging technologies such as MoonTag provides unprecedented resolution for studying translational heterogeneity [21]. Furthermore, the emergence of standardized workflows and shared computational resources is lowering barriers to implementation while improving reproducibility [15] [17].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these multi-omics integration approaches offer powerful tools for biomarker discovery, therapeutic target identification, and biosynthetic pathway elucidation. By systematically connecting genes to molecules, these methods accelerate the translation of basic research findings into clinical applications and biotechnological innovations.

Bioinformatic Tools for Pathway Prediction and Prioritization

Pathway analysis represents a cornerstone of modern bioinformatics, enabling a systems-level understanding of how genes, proteins, and metabolites cooperate to drive biological processes. By moving beyond single-molecule analysis to examine entire functional modules, researchers can decipher complex mechanisms underlying health, disease, and biosynthetic potential. The integration of pathway prediction and prioritization tools has become particularly crucial in biosynthetic product validation research, where identifying key pathways and their functional interactions accelerates the discovery and development of novel therapeutic compounds [22] [23].

The fundamental challenge in this domain lies in the accurate reconstruction of biological pathways from diverse omics data, followed by intelligent prioritization to identify the most promising targets for experimental validation. This process requires sophisticated computational tools capable of integrating multi-dimensional evidence from genomic context, expression patterns, protein interactions, and literature knowledge [22]. As the volume and complexity of biological data continue to grow, these bioinformatics tools have evolved to incorporate advanced artificial intelligence methods, substantially improving their predictive accuracy and utility for drug development professionals [24].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of leading pathway prediction and prioritization tools, examining their core methodologies, performance characteristics, and applications within analytical techniques for biosynthetic product validation research. By objectively evaluating the capabilities and limitations of each platform, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge needed to select optimal tools for their specific validation workflows and research objectives.

Comparative Analysis of Bioinformatics Tools

Tool Features and Applications

Table 1: Feature Comparison of Major Pathway Analysis Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Data Types Supported | Pathway Sources | Integration Capabilities | User Interface |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STRING | Protein-protein association networks | Proteins, genomic data | KEGG, Reactome, GO, BioGRID, IntAct | Cytoscape, R packages | Web-based, API |

| KEGG | Pathway mapping and analysis | Genomic, proteomic, metabolomic data | KEGG pathway database | BLAST, expression data | Web-based, programming APIs |

| Bioconductor | Genomic data analysis | RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, variant data | Multiple community packages | R statistical environment | Command-line, R scripts |

| Galaxy | Workflow management | NGS, sequence analysis | Custom and public pathways | Public databases, visualization tools | Web-based, drag-and-drop |

| GKnowMTest | Pathway-guided GWAS prioritization | GWAS summary data | User-specified pathways | R/Bioconductor | R package |

The STRING database stands out for its comprehensive approach to protein-protein association networks, integrating both physical and functional interactions drawn from experimental data, computational predictions, and prior knowledge [22]. Its recently introduced regulatory network capability provides information on interaction directionality, offering deeper insights into signaling pathways and regulatory hierarchies [22]. This makes STRING particularly valuable for mapping biosynthetic pathways where understanding the flow of molecular events is crucial for validation.

KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) offers a curated pathway database with extensive manual annotations, providing high-quality reference pathways for comparative analysis [25]. While its subscription model may present barriers for some users, its comprehensive coverage of metabolic and signaling pathways makes it invaluable for biosynthetic research, particularly when studying conserved biological processes across species [25].

Bioconductor represents a fundamentally different approach, offering a flexible, open-source platform for statistical analysis of genomic data [25]. With over 2,000 packages specifically designed for high-throughput biological data analysis, Bioconductor enables custom pathway analysis workflows but requires significant computational expertise and R programming knowledge to leverage effectively [25].

Galaxy addresses usability challenges by providing a web-based platform with drag-and-drop functionality, making complex pathway analyses accessible to researchers without programming backgrounds [25]. This democratization of bioinformatics comes with some limitations in advanced functionality compared to programming-based alternatives, but represents an excellent entry point for teams new to pathway analysis.

Specialized tools like GKnowMTest fill specific niches in the pathway analysis ecosystem, with this particular package designed for pathway-guided prioritization in genome-wide association studies [26]. By leveraging pathway knowledge to upweight variants in biologically relevant genes, it increases statistical power for detecting associations that might be missed through standard GWAS approaches [26].

Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Pathway Analysis Tools

| Tool Name | Scoring System | Accuracy Metrics | Computational Requirements | Scalability | Specialized Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STRING | Confidence scores (0-1) for associations | Benchmarking against KEGG pathways | Moderate (web-based) | Handles thousands of organisms | Regulatory networks, physical interactions |

| DeepVariant | Deep learning-based variant calling | >99% accuracy on benchmark genomes | High (GPU recommended) | Scalable via cloud implementation | AI-based variant detection |

| MAFFT | Alignment scoring algorithms | High accuracy for diverse sequences | Low to moderate | Handles large datasets | Fast Fourier Transform for speed |

| GKnowMTest | Weighted p-values | Maintains Type 1 error control | Moderate (R-based) | Genome-wide datasets | Pathway-guided GWAS prioritization |

| Rosetta | Energy minimization scores | High accuracy for protein structures | Very high (HPC recommended) | Limited by computational resources | AI-driven protein modeling |

Experimental validation studies provide critical insights into the real-world performance of these tools. In one comprehensive study focusing on tip endothelial cell markers, researchers employed the GKnowMTest framework to prioritize candidates from single-cell RNA-sequencing data [27]. The validation workflow successfully identified six high-priority targets from the top 50 congruent tip endothelial cell genes, four of which demonstrated functional relevance in subsequent experimental assays [27]. This represents a 40% validation rate for the top 10% of ranked markers, highlighting both the promise and challenges of computational prioritization.

The STRING database employs a sophisticated scoring system that estimates the likelihood of protein associations being correct, with scores ranging from 0 to 1 based on integrated evidence from genomic context, co-expression, experimental data, and text mining [22]. This probabilistic framework allows researchers to set confidence thresholds appropriate for their specific applications, balancing sensitivity and specificity according to their research goals.

Performance benchmarks for AI-driven tools like DeepVariant demonstrate the substantial impact of machine learning on bioinformatics accuracy. DeepVariant achieves greater than 99% accuracy on benchmark genomes, significantly outperforming traditional variant calling methods [25]. This improved detection is particularly valuable for identifying genetic variants in biosynthetic gene clusters that may impact compound production or function.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

In Silico Prioritization Workflow

The transition from computational prediction to experimental validation requires rigorous, reproducible protocols. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for pathway-based gene prioritization and validation:

Pathway-Guided Target Prioritization Workflow

This workflow implements the GKnowMTest framework for pathway-guided prioritization, which begins with genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary data and a user-specified list of pathways [26]. The method maps SNPs to genes based on physical location and then to pathways, estimating the prior probability of each SNP being truly associated based on pathway enrichment [26]. The algorithm employs penalized logistic regression to automatically determine the relative importance of pathways from the GWAS data itself, avoiding subjective prespecification of "important pathways" that could lead to power loss [26].

The core innovation of this approach lies in its data-driven weighting strategy, where SNPs clustering in enriched pathways receive higher weights, thereby increasing their probability of detection while maintaining the overall false-positive rate at standard genome-wide significance thresholds [26]. This method has demonstrated improved power in both simulated and real GWAS datasets, including studies of psoriasis and type 2 diabetes, without inflating Type 1 error rates [26].

Functional Validation Techniques

Following computational prioritization, experimental validation is essential to confirm biological function. The diagram below outlines a standard functional validation protocol for prioritized pathway components:

Experimental Validation Workflow for Pathway Components

This validation protocol employs multiple complementary assays to assess the functional impact of perturbing prioritized pathway components. As demonstrated in a recent tip endothelial cell study, researchers used three different non-overlapping siRNAs per gene to ensure robust target knockdown, then selected the two most effective siRNAs for functional characterization [27]. This approach controls for off-target effects and strengthens confidence in the observed phenotypes.

Functional assays typically evaluate key cellular processes relevant to the pathway under investigation. In the angiogenesis study, researchers employed 3H-thymidine incorporation to measure proliferative capacity and wound healing assays to assess migratory potential [27]. For sprouting assays—a hallmark of tip endothelial cell function—they utilized in vitro models that recapitulate the complex morphogenetic processes of blood vessel formation [27].

The integration of CRISPR gene editing has revolutionized functional validation by enabling more precise genetic perturbations [23]. In microbial natural products research, CRISPR facilitates targeted activation or repression of biosynthetic gene clusters, allowing researchers to test hypotheses about pathway function and product formation [23]. This approach is particularly valuable for studying silent gene clusters that are not expressed under standard laboratory conditions but may encode novel bioactive compounds [23].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Pathway Validation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perturbation Tools | siRNA, CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Targeted gene knockdown/editing | Functional validation of prioritized genes |

| Antibodies | Phospho-specific, protein-specific | Protein detection and localization | Western blot, immunofluorescence |

| Cell Culture Models | HUVECs, specialized cell lines | In vitro functional studies | Migration, proliferation, sprouting assays |

| Sequencing Reagents | RNA-Seq kits, single-cell reagents | Transcriptomic profiling | Validation of expression changes |

| Pathway Reporters | Luciferase constructs, GFP reporters | Pathway activity monitoring | Signaling pathway validation |

| Bioinformatics Kits | Library prep kits, barcoding systems | Sample multiplexing | High-throughput validation studies |

Effective pathway validation requires carefully selected research reagents that enable specific, reproducible experimental readouts. Perturbation tools such as siRNA and CRISPR/Cas9 systems form the foundation of functional studies, allowing researchers to specifically modulate the expression of prioritized pathway components [27]. Best practices recommend using multiple non-overlapping siRNAs per target to control for off-target effects and strengthen confidence in observed phenotypes [27].

Advanced cell culture models provide the biological context for validation experiments. Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) represent one well-established system for studying angiogenic pathways, but researchers should select model systems that best recapitulate the biological context of their pathway of interest [27]. For microbial natural products research, this may involve specialized bacterial strains or heterologous expression systems that enable manipulation of biosynthetic gene clusters [23].

High-quality antibodies remain essential for validating protein-level expression, post-translational modifications, and subcellular localization. Phospho-specific antibodies can provide crucial insights into signaling pathway activation, while protein-specific antibodies confirm successful knockdown of target genes [27]. The expanding toolbox of pathway reporter systems, including luciferase and GFP-based constructs, enables real-time monitoring of pathway activity in response to genetic or pharmacological perturbations.

The integration of pathway prediction and prioritization tools has fundamentally transformed biosynthetic product validation research, enabling more targeted and efficient experimental workflows. As this comparison demonstrates, the current bioinformatics landscape offers diverse solutions ranging from comprehensive protein network databases like STRING to specialized statistical frameworks like GKnowMTest, each with distinct strengths and optimal applications [22] [26].

The continuing evolution of AI-driven analysis methods promises further improvements in prediction accuracy and computational efficiency [24]. However, even the most sophisticated algorithms cannot replace careful experimental validation, as demonstrated by studies where only a subset of top-ranked computational predictions showed functional relevance in biological assays [27]. This underscores the importance of maintaining a tight integration between computational prediction and experimental validation throughout the research process.

For researchers in biosynthetic product validation, the selection of pathway analysis tools should be guided by specific research questions, available datasets, and technical expertise. Comprehensive platforms like KEGG and STRING offer extensive curated knowledge bases for hypothesis generation [25] [22], while flexible programming environments like Bioconductor enable custom analytical approaches for specialized applications [25]. As these tools continue to mature and incorporate emerging technologies like large language models for literature mining [22] and deep learning for pattern recognition [24], they will undoubtedly unlock new opportunities for discovering and validating novel biosynthetic pathways with therapeutic potential.

Analytical Methodologies: Structural Elucidation and Functional Assessment

Chromatographic Separation and Hyphenated Techniques (LC-MS, GC-MS)

In the fast-paced world of analytical chemistry, particularly within biosynthetic product validation research, the demand for greater sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency is constant [28]. As sample matrices become more complex and detection limits push into the parts-per-trillion range, traditional single-technique methods often fall short. Hyphenated techniques—the powerful combination of two or more complementary analytical methods—have become indispensable in this landscape [28]. By linking a separation technique directly to a detection technique, these integrated systems unlock a new level of analytical power, allowing researchers to achieve unprecedented results in the identification and quantification of chemical compounds [28].

For scientists engaged in drug development and natural product research, understanding these techniques is not merely advantageous—it's a necessity [28]. These methods serve as the workhorses for validating the purity, identity, and quantity of biosynthetic products, from initial discovery through to quality control. The core principle underpinning hyphenated techniques is synergy: chromatography efficiently separates complex mixtures into individual components, while spectrometry provides definitive structural identification [29]. This review focuses on two of the most impactful hyphenated systems—Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)—providing a detailed comparison of their principles, applications, and performance to guide method selection in research and development.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Comparisons

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

LC-MS combines the separation power of Liquid Chromatography (LC) with the qualitative and quantitative capabilities of Mass Spectrometry (MS) [28]. The process begins in the liquid chromatograph, where a liquid mobile phase carries the sample through a column packed with a stationary phase [28]. Components in the sample separate based on their differential partitioning between the mobile and stationary phases, with each compound exiting the column at a specific retention time [28].

The separated components are then introduced into the mass spectrometer via a critical interface that ionizes the compounds without losing chromatographic resolution [28]. Common soft ionization techniques include Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), which are crucial for producing intact molecular ions from fragile or non-volatile molecules [28] [29]. Once ionized, the ions are directed into a mass analyzer where they are separated based on their unique mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), producing a mass spectrum that serves as a molecular fingerprint for each compound [28].

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

GC-MS represents the complementary hyphenated technique to LC-MS, specifically designed for analyzing volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds [28]. The process initiates in the gas chromatograph, where a gaseous mobile phase (typically helium or nitrogen) carries the vaporized sample through a heated column [28] [30]. Compounds with lower boiling points and less affinity for the stationary phase move faster, achieving separation based on volatility and interaction with the column [28].

As each separated component exits the GC column, it enters the mass spectrometer through a heated interface [28]. Unlike LC-MS, the compounds are already in the gas phase. In the MS, the compounds are typically subjected to high-energy Electron Ionization (EI), which fragments the molecules into a characteristic pattern of smaller, charged ions [28] [29]. The resulting ions are separated by their m/z ratio, creating a distinct fragmentation pattern that serves as a highly reproducible chemical fingerprint for identification against extensive reference libraries [28].

Comparative Technical Specifications

Table 1: Fundamental comparison of LC-MS and GC-MS techniques

| Parameter | LC-MS | GC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Principle | Differential partitioning between liquid mobile phase and solid stationary phase | Volatility and interaction with stationary phase with gas mobile phase |

| Sample State | Liquid | Gas (after vaporization) |

| Ionization Techniques | Electrospray Ionization (ESI), Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) [28] [29] | Electron Ionization (EI), Chemical Ionization (CI) [28] [29] |

| Ionization Process | Soft ionization (often produces intact molecular ions) [28] | Hard ionization (often produces fragment ions) [28] |

| Optimal Compound Types | Non-volatile, thermally labile, high molecular weight compounds [28] [31] | Volatile, semi-volatile, thermally stable compounds [28] [31] |

| Molecular Weight Range | Broad range, including large biomolecules [31] | Typically lower molecular weight compounds [31] |

| Derivatization Requirement | Generally not required | Often required for non-volatile or polar compounds [29] [31] |

Comparative Experimental Performance Data

Analysis of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs)

A comprehensive study comparing LC-MS and GC-MS for analyzing PPCPs in surface water and treated wastewaters revealed significant performance differences [32]. Researchers employed high-performance liquid chromatography-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (HPLC-TOF-MS) and GC-MS to monitor a panel of PPCPs and their metabolites, including carbamazepine, iminostilbene, oxcarbazepine, epiandrosterone, loratadine, β-estradiol, and triclosan [32].

Table 2: Performance comparison of LC-MS and GC-MS in PPCP analysis [32]

| Performance Metric | LC-MS | GC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Method | Liquid-liquid extraction provided superior recoveries | Liquid-liquid extraction provided superior recoveries |

| Detection Limits | Lower detection limits achieved | Higher detection limits compared to LC-MS |

| Analyte Coverage | Detected a broader range of PPCPs and metabolites | Limited to volatile and derivatized compounds |

| Sample Preparation | Less extensive preparation required | Often requires derivatization for polar compounds |

| Suitability for Metabolites | Excellent for parent compounds and metabolites | Limited unless metabolites are volatile or derivatized |

The study concluded that HPLC-TOF-MS provided superior detection limits for the target analytes, which is crucial for environmental monitoring where these compounds typically exist at trace concentrations [32]. Furthermore, the sample preparation for LC-MS was less extensive, increasing laboratory throughput—an important consideration for high-volume testing environments [32].

Benzodiazepine Analysis in Urinalysis

A rigorous comparative analysis of LC-MS-MS versus GC-MS was performed for urinalysis detection of five benzodiazepine compounds as part of the Department of Defense Drug Demand Reduction Program testing panel [33]. The study evaluated alpha-hydroxyalprazolam, oxazepam, lorazepam, nordiazepam, and temazepam around the administrative decision point of 100 ng/mL [33].

Table 3: Method performance comparison for benzodiazepine analysis [33]

| Performance Characteristic | LC-MS-MS | GC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Average Accuracy (%) | 99.7 - 107.3% | Comparable to LC-MS-MS |

| Precision (%CV) | <9% | Comparable to LC-MS-MS |

| Sample Preparation Time | Shorter | Longer, requiring derivatization |

| Extraction Efficiency | High with simplified procedures | High but with more steps |

| Analysis Time | Shorter run times | Longer chromatographic runs |

| Matrix Effects | Observed but controlled with deuterated IS | Less pronounced |

| Throughput | Higher | Lower |

Both technologies produced comparable accuracy and precision for control urine samples, demonstrating that either technique can provide legally defensible results in forensic contexts [33]. However, the ease and speed of sample extraction, the broader range of analyzable compounds, and shorter run times make LC-MS-MS technology a suitable and expedient alternative confirmation technology for benzodiazepine testing [33]. A notable finding was the 39% increase in nordiazepam mean concentration measured by LC-MS-MS due to suppression of the internal standard ion by the flurazepam metabolite 2-hydroxyethylflurazepam, highlighting the importance of appropriate internal standards and method validation [33].

Application Workflows and Decision Pathways

Analytical Selection Workflow

The choice between LC-MS and GC-MS depends on multiple factors related to the analyte properties and research objectives. The following workflow diagram provides a systematic approach to technique selection:

Sample Preparation Protocols

For urine sample analysis using LC-MS-MS, the protocol involves:

- Sample Volume: Use 0.5 mL urine aliquots

- Internal Standard Addition: Add appropriate deuterated internal standards (e.g., AHAL-d5, OXAZ-d5, LORA-d4, NORD-d5, TEMA-d5)

- Solid-Phase Extraction: Employ Clean Screen XCEL I solid-phase extraction columns

- Extraction Conditions: Condition columns with methanol and water before sample loading

- Washing: Wash with water and methanol/water mixtures to remove interferents

- Elution: Elute analytes with methylene chloride/methanol/ammonium hydroxide (85:10:2)

- Evaporation: Evaporate extracts to dryness under nitrogen stream

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute in mobile phase compatible solvent for LC-MS-MS analysis

This protocol emphasizes minimal sample preparation without derivatization, significantly reducing processing time compared to GC-MS methods [33].

For comparable benzodiazepine analysis using GC-MS:

- Sample Volume: Use 1 mL urine aliquots

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Incubate with β-glucuronidase (type HP-2) in sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.75) for 60 minutes at 55°C to hydrolyze conjugates

- Internal Standard Addition: Add deuterated internal standards (AHAL-d5, OXAZ-d5, NORD-d5, TEMA-d5)

- Solid-Phase Extraction: Use CEREX CLIN II cartridges under positive pressure (1 mL/min)

- Cartridge Conditioning: Wash with carbonate buffer (pH 9), water-acetonitrile (80:20), and water

- Drying: Dry cartridges for 15 minutes at 50 psi

- Elution: Elute with methylene chloride/methanol/ammonium hydroxide (85:10:2)

- Derivatization: Convert to tert-butyldimethylsilyl derivatives using MTBSTFA with 1% MTBDMCS at 65°C for 20 minutes

- Analysis: Transfer to GC-MS for analysis

The derivatization step is necessary for many compounds analyzed by GC-MS to improve volatility and thermal stability [29] [33].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of hyphenated techniques requires specific reagent systems tailored to each methodology. The following table outlines critical reagents and their functions in LC-MS and GC-MS analyses.

Table 4: Essential research reagents for hyphenated techniques

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Analysis | Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase Modifiers | Formic acid, Ammonium acetate, Ammonium formate [32] [34] | Improve ionization efficiency and chromatographic separation | LC-MS |

| Derivatization Reagents | MTBSTFA (with 1% MTBDMCS) [33], N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) | Enhance volatility and thermal stability of analytes | GC-MS |

| SPE Sorbents | C18-bonded silica [32], Mixed-mode polymers [33] | Extract and concentrate analytes from complex matrices | Both |

| Enzymes | β-Glucuronidase (Type HP-2) [33] | Hydrolyze conjugated metabolites to free forms | Both |

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Benzodiazepine-d5 standards, Drug metabolite-d4 standards [33] | Correct for matrix effects and extraction efficiency variations | Both |

| Chromatographic Columns | C18 reverse-phase columns (e.g., Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18) [32], DB-5MS capillary columns [32] | Separate complex mixtures into individual components | Both |

LC-MS and GC-MS represent complementary rather than competing technologies in the analytical chemist's toolkit for biosynthetic product validation. LC-MS excels in analyzing non-volatile, thermally labile, and high-molecular-weight compounds, making it indispensable for pharmaceutical applications, proteomics, metabolomics, and environmental analysis of polar contaminants [28] [31]. Conversely, GC-MS remains the superior technique for volatile and semi-volatile compounds, maintaining its status as the "gold standard" in forensic toxicology, environmental VOC monitoring, and petroleum analysis [28] [33].

The decision between these hyphenated techniques should be guided by the physicochemical properties of the analytes, the required sensitivity and specificity, and practical considerations regarding sample throughput and operational costs [31]. While GC-MS offers robust, reproducible results with extensive spectral libraries for compound identification, LC-MS provides broader compound coverage with minimal sample preparation [33]. Advances in both technologies continue to expand their capabilities, with LC-MS increasingly handling larger molecular weight biomolecules and GC-MS benefiting from improved derivatization techniques for polar compounds [31].

For researchers validating biosynthetic products, understanding these complementary strengths enables appropriate method selection based on specific analytical requirements, ultimately ensuring accurate characterization of chemical identity, purity, and quantity throughout the drug development pipeline.

Advanced Spectroscopic Methods (NMR, HRMS, IM-MS)

In the field of biosynthetic product validation research, the confirmation of molecular identity, purity, and structure is paramount. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS), and Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry (IM-MS) have emerged as three cornerstone analytical techniques, each providing unique and complementary data for comprehensive molecular characterization [35]. While Mass Spectrometry (MS) has become the predominant tool in many laboratories due to its high sensitivity and throughput, its inherent limitations in providing detailed structural information can hinder complete compound identification [35]. NMR spectroscopy remains unrivaled for definitive structural and stereochemical elucidation at the atomic level, though it requires more material and lacks the sensitivity of MS-based methods [36] [37]. IM-MS introduces an orthogonal separation dimension based on molecular size and shape in the gas phase, enhancing selectivity and providing structural insights that complement both NMR and HRMS [38]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform their optimal application in research and drug development.

Technical Comparison of NMR, HRMS, and IM-MS

The selection of an analytical technique is a critical decision that can directly impact the quality and depth of research outcomes. The table below provides a quantitative and qualitative comparison of NMR, HRMS, and IM-MS across key performance metrics relevant to biosynthetic product validation.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of NMR, HRMS, and IM-MS in Metabolomics and Drug Development

| Feature/Parameter | NMR | HRMS | IM-MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Low (μM range) [36] | High (nM range) [36] | High (nM range, enhanced selectivity) [38] |

| Reproducibility | Very High [39] | Average [39] | High (CCS values are highly reproducible) [38] |

| Structural Detail | Full molecular framework, stereochemistry, atomic connectivity, and dynamics [40] | Molecular formula, fragmentation pattern, functional groups from MSâ¿ [35] | Gas-phase size and shape (Collision Cross Section - CCS) [38] |

| Stereochemistry Resolution | Excellent (e.g., via NOESY/ROESY) [40] | Limited [40] | Limited for enantiomers; can separate some diastereomers and conformers [38] |

| Quantification | Inherently quantitative without standards [36] | Requires standards for accurate quantification [36] | Requires standards; CCS can aid in isolating targets for quantitation |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; often minimal chromatographic separation needed [36] | More complex; often requires chromatography (LC/GC) and derivatization [36] [39] | Similar to HRMS; integrated with LC for complex mixtures [38] |

| Sample Recovery | Non-destructive; sample can be recovered [36] | Destructive; sample is consumed [36] | Destructive; sample is consumed [38] |

| Key Applications in Validation | Structure elucidation, stereochemistry, impurity identification (isomers), metabolite ID, reaction monitoring [37] [40] | Metabolite profiling, high-throughput screening, biomarker discovery, targeted analysis [36] [35] | Separating complex mixtures, identifying isomeric metabolites, enhancing confidence in compound ID [38] |

Detailed Experimental Methodologies

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

1. Sample Preparation for Metabolomics: The following protocol for analyzing plant metabolites, as used in wheat biostimulant studies, ensures high-quality, reproducible results [41].

- Tissue Processing: Snap-freeze plant material (e.g., roots, stems, leaves) in liquid nitrogen and lyophilize. Homogenize the freeze-dried tissue into a fine powder using a ball mill.

- Metabolite Extraction: Weigh 100 mg of powdered tissue and mix with 800 μL of a 1:1 (v/v) water/methanol solution. Extract the mixture for 10 minutes at 60°C in a ThermoMixer at 2000 rpm, followed by 30 minutes of sonication in a 35 kHz ultrasonic bath at 60°C.

- Centrifugation and Recovery: Centrifuge the sample at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube.

- Repeat Extraction: Repeat the extraction process twice more on the remaining pellet, combining all supernatants for a final volume of approximately 2.4 mL.

- NMR Sample Preparation: Take an 800 μL aliquot of the combined supernatant and dry it in a speed vacuum concentrator. Reconstitute the dried extract in 800 μL of a deuterated solvent mixture, typically methanol-d₄ and KH₂PO₄ buffer in D₂O (0.1 M, pD 6.0), containing 0.0125% TMSP (internal chemical shift reference) and 0.6 mg/mL NaN₃ (antimicrobial agent). Vortex, sonicate, centrifuge, and transfer the clear supernatant to a 5 mm NMR tube for analysis [41].

2. Data Acquisition:

- 1D ¹H-NMR: Data are typically acquired on a 600 MHz spectrometer. For quantitative analysis, a simple 1D pulse sequence with water presaturation is used, collecting data at 131K points over 128 scans with a relaxation delay of 25 seconds to ensure full longitudinal relaxation for accurate integration [41].

- 2D NMR: For structural elucidation in complex mixtures, two-dimensional experiments are essential.

- ¹H-¹³C Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (HSQC): Identifies direct correlations between protons and their directly bonded carbon atoms, defining the CH framework of the molecule [40].

- ¹H-¹³C Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation (HMBC): Detects long-range couplings (typically 2-3 bonds) between protons and carbons, enabling the connection of structural fragments through quaternary carbons [40].

- Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy (NOESY): Provides information on through-space interactions between protons, which is critical for determining relative stereochemistry and three-dimensional conformation [40].

High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS)

1. Multi-Attribute Method (MAM) for Monoclonal Antibodies: This LC-MS workflow is used for comprehensive characterization of therapeutic proteins, including glycosylation and other post-translational modifications [42].

- Sample Digestion:

- Reduction and Alkylation: Denature 50 μg of the monoclonal antibody (e.g., Rituximab) in 7.5M guanidine hydrochloride. Reduce disulfide bonds with 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Alkylate the free thiols with 20 mM iodoacetic acid (IAA) for 20 minutes in the dark.

- Desalting: Quench the alkylation reaction with an additional 10 mM DTT and desalt the protein using a Zeba spin desalting column equilibrated with 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer.

- Trypsin Digestion: Add trypsin at a 1:10 (w/w) enzyme-to-substrate ratio. Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes to generate peptides and glycopeptides. Quench the reaction with formic acid.

- LC-MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Separate the tryptic digest using reversed-phase liquid chromatography (e.g., C18 column) with a gradient of water and acetonitrile, both modified with 0.1% formic acid.

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze the eluent using a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-Exactive Orbitrap). Data are typically acquired in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode, where a full MS scan is followed by MS/MS scans of the most intense ions.

- Data Processing: Use specialized software (e.g., Thermo Chromeleon) to identify and quantify product quality attributes (PQAs) like glycoforms based on their accurate mass and retention time [42].

Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry (IM-MS)

1. Drug Metabolite Identification and Isomer Separation: This protocol leverages the orthogonal separation of IM-MS to address the challenge of isomeric drug metabolites [38].

- Sample Preparation: Extract drugs and metabolites from biological matrices (e.g., blood, urine) using standard protein precipitation or solid-phase extraction methods.

- LC-IM-MS Analysis:

- Liquid Chromatography: First-dimension separation is performed using conventional LC (e.g., reversed-phase) to reduce sample complexity.

- Ion Mobility: The LC eluent is introduced into the IM drift cell. In a Travelling Wave IM (TWIM) instrument, ions are propelled through a neutral buffer gas (e.g., nitrogen or helium) by a dynamic electric field. Ions with a smaller collision cross section (CCS) experience fewer collisions and traverse the cell faster than larger, more extended ions.

- Mass Spectrometry: The mobility-separated ions are then analyzed by a high-resolution mass spectrometer.

- Data Interpretation:

- The drift time is converted into a collision cross section (CCS), a reproducible physicochemical identifier of an ion's gas-phase size and shape.

- CCS values are used to distinguish isomeric metabolites that have identical mass-to-charge ratios but different structures. The presence of multiple peaks in the arrival time distribution for a single m/z value indicates isomeric species or different gas-phase conformers [38].

- CCS databases serve as an orthogonal filter for confident metabolite identification, increasing confidence beyond retention time and mass fragmentation alone.

Visual Workflows for Technique Selection and Application

The following diagrams illustrate the logical decision pathway for technique selection and the specific experimental workflow for integrated analysis.

Figure 1: A decision tree for selecting the most appropriate spectroscopic technique based on the primary research question in biosynthetic product validation.

Figure 2: A simplified workflow for LC-IM-MS analysis, showing how chromatographic, mobility, and mass spectrometric separations are combined to generate multidimensional data for confident compound identification.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of these advanced spectroscopic methods relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experimental protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., Dâ‚‚O, Methanol-dâ‚„) | Provides a magnetic field frequency lock for the NMR spectrometer and eliminates large solvent proton signals that would otherwise overwhelm analyte signals. | NMR sample preparation for metabolomics [41]. |

| Internal Standard (e.g., TMSP) | Serves as a reference point (0.0 ppm) for chemical shift calibration in NMR spectra and can be used for quantitative concentration determination. | NMR sample preparation [41]. |

| PNGase F Enzyme | Catalyzes the cleavage of N-linked glycans from glycoproteins between the innermost GlcNAc and asparagine residues for detailed glycosylation analysis. | Released glycan analysis for monoclonal antibodies [42]. |

| Fluorescent Tags (e.g., 2-AB, RapiFluor-MS) | Label released glycans to enable sensitive fluorescence detection (HILIC-FLD) and/or enhance ionization efficiency for MS analysis. | HILIC-FLD and LC-MS of N-glycans [42]. |

| Trypsin Protease | A specific protease that cleaves peptide bonds at the C-terminal side of lysine and arginine residues, generating peptides and glycopeptides suitable for LC-MS analysis. | Protein digestion for the Multi-Attribute Method (MAM) [42]. |

| Ion Mobility Buffer Gas (e.g., Nâ‚‚, He) | An inert gas that fills the ion mobility drift cell; ions are separated based on their collisions with this gas under the influence of an electric field. | IM-MS separation of drug metabolites and isomers [38]. |